5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Inkspot Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

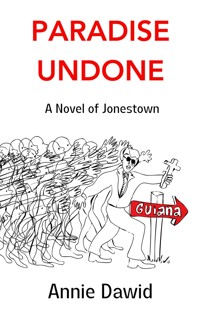

Paradise Undone, A Novel of Jonestown is a part real, part imagined retelling of the tragic events that led to the USA's biggest single loss of civilian life in the twentieth century. On November 18th 1978, nine hundred and nine people died in the Guyanese jungle. Published on the 45th anniversary, Annie Dawid's compelling story of Jonestown explores the tragedy through the voices of four protagonists - Marceline Baldwin Jones and three other members of Peoples Temple. Drawing on extensive research and interviews, Annie Dawid blends fact and fiction, using real and composite characters to tell a story about the horrific mass murder/suicide that took place in the Guyanese jungle, all because of one man with a God complex.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 472

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

A Note to the Reader

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Epilogue

Publications

Also by Annie Dawid

Acknowledgements

First edition published in 2023 by Inkspot Publishing

www.inkspotpublishing.com

All rights reserved

© Annie Dawid, 2023

The right of Annie Dawid to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the author, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-916708-01-3

ISBN (Paperback US) 978-1-916708-02-0

ISBN (Paperback ex-US): 978-1-916708-00-6

Cover Image: Joe Samuels

For Christine, who refused to submit.

This novel is based on true events. Some dialogue has been taken verbatim from Jonestown documents.

Some individuals who died on Nov. 18, 1978, among them Jim and Marceline Jones, are referred to by their real names, though they are products of research and imagination. Others are fictions.

IF YOU WANT TO CALL ME GOD,

THEN I’M GOD.

Jim Jones

“The first body I saw was off to the side, alone. Five more steps and I saw another and another and another; hundreds of bodies. The Newsweek reporter was walking around saying, “I don’t believe it, I don’t believe it.” Another guy said, “It’s unreal.” Then nobody even attempted to speak anymore. It was overwhelming. Bizarre.”

“I started moving to my left, and I was battered by the smell. It hit me. Went right into my chest. I started to gag, and turned my back. Seeing it, plus the smell … Then, I found if I kept my eyes moving and let my camera be my eyes, I’d never really see it. I shot verticals and horizontals, moving to my left. And there it was. There were piles upon piles of bodies. What do you call it? There’s no definition. Nothing to compare it to.”

Rolling Stone

January 1979

Watts Freeman

10:05 a.m.

November 18, 2008

San Francisco

KR:Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview, Mr. Freeman. I know our listeners on KBBA, the Black Bay Area’s radio station, are very grateful. First, let me do a quick test. Today is November the eighteenth, 2008, the thirty-year anniversary of the Jonestown massacre, and I’m Kenyatta Robinson. Test. Good.

WF:I go by Watts.

KR: Okay, Watts. That tells us something important about you already, and we haven’t even gotten to the first question! Just relax; the lapel mike will catch everything. Later, we can edit out all the dead space and mumbling. I’d like you to talk about what strikes you most on this date. But I do have a few questions to start with. For instance, can you tell us about when you met Jim Jones?

WF: I’m a teenager, right? Don’t know shit, but I think I know everything. Think I’ve got the whole scam down cold, but really, I was deeply fucked up. Is it all right, me cussing on tape?

KR: No problem. Like I said, we can edit later. Use whatever language feels most comfortable.

WF: Well, English is all I know. [Laughter] Anyway, I was pretty much living on the streets back then. This was in LA, Watts area mostly. I’d come up here to the Bay Area with some friends and we were looking around, thinking about moving since the cops in LA were seriously out of control.

KR: How old were you exactly? And when was this?

WF: Around ’68, ’69 maybe. I was born in ’50. Anyway, that stretch of time is pretty hazy ’cause most days I had a good buzz on. So me and my friends, we’re checking out Oakland, scratching around Hunter’s Point, and then we’re up in the Fillmore, and we see these buses, a whole parade of them, man, coming down Fillmore Street, and they’re full of brothers and sisters. Some white folks too but mostly brothers and sisters and they’re waving. Waving at us, hanging on the corner, stoned into tomorrow. That was my first sight of Peoples Temple. Didn’t see Jimmie Jones that day though. Mind if I smoke?

KR: It’s your home, Mr. Freeman –

WF: Watts. Please. But does it bother you? ’Cause if it does, I won’t. You a beautiful woman in your childbearing years; how do I know you ain’t pregnant?

KR: [Laughs] I’m not. You’re fine.

WF: You pretty fine yourself. [Sound of his palm slapping his cheek] Sorry. Am I making you uncomfortable? Shit. Same ol’ same ol’ Watts. Jimmie Jones figured me out in about five minutes, but the thing was, I figured him in about four, so generally I was one step ahead.

KR: I hope to hear more about that, Watts. But, to continue where we were, you say you didn’t meet the Reverend Jones on that day. So, when did that happen?

WF: 1970. In LA. I was selling dope and doing dope and not much else. My old lady at the time had kicked me out, so I go visit my grandma to get something to eat, and she drag me off to one of them healing services she love. I was too stoned to refuse. She always believing in something, my grandma, something to make her life feel better than it did. God or Jimmie Jones or Jesus or somebody else. So when she found God and Jesus wrapped up in Reverend Jimmie Jones, she was like to be in heaven.

KR: Can you describe your earlier life, growing up in Watts?

WF: And growing up as Watts, right? [Laughter] I guess my father was a doper. Never knew him. He died when my mother was pregnant. A dealer too. It was never exactly clear whether he OD’d or got done on the street for ripping somebody off. Doesn’t matter. Dead is dead, right? My mother did dope too, and she didn’t last long. I moved around, from practically the minute I was born, from one relative to another in Watts, and some of those people weren’t in any better shape than my mother. They tried to be good to me; I can see that now. But it was rough, coming up like that. My grandma was working all the time, cleaning houses and such, so I couldn’t stay with her. I didn’t get to school much, and when I did, recess was where I started doping. I was eleven, but I’d sampled all kinds of shit before then. Every now and again, I did stay with my grandma, but my mama and her didn’t get along ’cause Grandma always telling her what she was doing wrong, which was everything, of course, so even though my mama was too fucked up – ’scuse me, too messed up to take care of me herself, she didn’t like my being with her mama. So then after some big fight, I’d get sent out to somebody else’s place.

KR: Sounds like your grandmother was a source of stability for you.

WF: [Laughs.] My grandma, she like every other old black lady in Peoples Temple. Sweet. A serious backbone for work. At the same time, you could talk her out of anything you needed and decided she didn’t. Like money. Stuff to pawn. And I did. Just like Jimmie Jones convincing every one of them grandmas to turn over their Social Security checks every month. Yeah, I’m guilty too, but that was before the Jimmie Jones years in LA. When the Temple finally got its own building there, she would’ve given every penny in her purse to those collections. Sometimes they had four or five in one service. And her pitiful possessions too, but she died before they could completely rip her off. Before I could, too.

KR: You sound bitter.

WF: Mostly, I’m pissed at myself. I was a nasty character back then. Hope I’m not so nasty anymore. Anyway, my grandma passed from natural causes. She wasn’t one of them widows lying face down in the mud, swollen up like a goddamn balloon in Jonestown. I’m not sure if dying of a heart attack in a rat-hole project in Watts is better than that, but at least she got buried proper.

KR: So, did you join up that day? With your grandmother? You were twenty then?

WF: Old enough to know better. Nah, not that day. But Jimmie Jones talking about how he’s a nigger like the rest of us, and how the government hates black people. Second part of that is true anyway. He says look at the Japanese. They had money, he says, they owned a chunk of California, and they got put into camps here ’cause they ain’t white. Not so long ago either. Like the Jews in Europe. He says, Don’t think it can’t happen here. And he goes on about how the white man wants us to be drunk and stoned and wasting our lives, and how we play right into their pale ugly hands when we get messed up on dope and booze. Asks us who own all the liquor stores in the ghetto. White people, right? He still right. ’Cept now it’s mostly Asians. Anyway, he’s talking like his skin is brown as yours or mine. Which I think is weird, ’cause the man is white. He ain’t mixed, not Indian, like he claim. He a white boy. He got that dark hair from Wales, not no Cherokee Nation. [Laughs] Anyway, he’s talking about this program they have at the church to get people like me, like a lot of young folk, off the dope and out of jail, to help us be useful in the community. It’s not like I never heard what the man said before, but he got a good rap and a fine delivery, and it’s penetrating my stoner head. Then my grandma gets on me, and she won’t quit razzing me ’til I say yes. Now, I’d done rehab already, and I’d been to jail already, and you know, I didn’t have nothing going on that was worth keeping going on. My girlfriend say she don’t want nothing to do with me ’cause I’m too fucked up – sorry, too messed up – too much of the time. So, Grandma says I can stay with her if I enroll myself in that program.

KR: So it worked? The Reverend Jones straightened you out?

WF: Kenyatta – that your name, right? Kenyatta, you gotta remember I was young at the time. And dumb. Dumb about dope, ’specially. But it wasn’t Jimmie Jones got me off the dope; it was the people in Peoples Temple. Man, they were some fine people. Some very fine people. That’s what always trips me up. To this day it does. Trips everyone else up too. All those good people. They weren’t crazy like Jimmie Jones. Anyway, the nurses running the program, the other folks helping us get through the first days, like Jim McElvane, the guy everyone called Mac, and Archie, and of course some of the other dopers, like Rufus. They got me through.

KR: Can you talk more about that, about what you call the “fine” people and how you still find it hard to understand what they did, three decades on?

WF: Well, you know how they showed us in the media – not first-hand of course, you too young – but you must have checked out the newspapers and the magazines, and the shit they had on TV.

KR: Yes. I did quite a lot of research for this interview. And I’m probably not as young as you think, Watts.

WF: You way younger than me, that’s for sure. [Laughs] Good old Watts hit the big five-eight this year, no thanks to Jimmie Jones. A miracle just the same, though. Never thought I’d get to be twenty-eight, much less fifty-eight, not what I was doing back then, the time we’re talking about. What I was saying was that the news made out all of Jonestown was psychos and sickos and brainwashed, brainless zombies. So far from the truth, Kenyatta. You know, that group of black people about the most together bunch of people I ever saw. True then and maybe truer today. It was the Reverend himself, as you call him, who was crazed and drugged out and sick. The inner circle, what I call the “white chick circle,” though there were some dudes in it too, mostly white – they like slaves to their master. “Yassuh, Dad.” Yassuh all day and all night. “Yassuh, Dad. Whatever you say, Dad.” He built himself such a bunch of yes men and yes women that if he say night is day they say, “Yes Dad, that’s right: Night is day.” He say day night, they say, “Thank you Dad – Day sho’nuff is night.” You want a cigarette?

KR: No thank you. I don’t smoke. But go ahead. It really doesn’t bother me.

WF: You sure you ain’t pregnant? Maybe you should say you are so I won’t smoke so much.

KR: Okay, Watts. Let’s say I am then. For the sake of your lungs. [Laughs]

WF: You funny. You a funny, smart lady, talking about my lungs. What I already put my body through it don’t make sense I ain’t dead. Now I think the diabetes gonna kill me in the end.

KR: I read that the Reverend Jones – Jimmie, as you call him – was actually very ill during those last days. Is that true?

WF: Hard to say for sure. He a star hypochondriac for certain. Had his wife checking his blood pressure every five minutes and he announce his fever over the PA, going up one degree every hour on the hour. Make people feel sorry for him. I don’t think he any sicker than the rest of us in that Jonestown heat, with the bugs and the worms and the water sometimes giving us the runs. And he did like his dope, especially that last year after his mama died. You study those pictures from November 18th, the interviews he give those press guys he had killed on the runway, and you see a user’s face. User’s shaky hands. Even his bloated belly in that death picture look like an addict’s body. He smacking his lips that whole talk he have with NBC like any cokehead. The media want to make all the black folk crazy to follow him, but he the insane one, not us. Night and day, he attended hand and foot by his private nurses and the doctor – most of them white – all of them revering his ass, and at the same time not helping him at all by giving him whatever drug he ask for: painkiller, sleeping pills, wake up pills, those so-called Vitamin B-12 shots the famous folks like so much.

KR: Who was the doctor? His name is escaping me.

WF: Larry Schacht. The last six months or so I was one of Doc Schacht’s heavy lifters, and I saw every pill and potion got delivered to that shed. They call it the Bond down there. Ten thousand doses of Thorazine we had, biggest stockpile in South America. You know what Thorazine is? To make the living dead, especially if they troublemakers. Funny I just called him Doc. Behind his back, me and Rufus call him King Doper. Like us, the man came to the Temple with a serious drug habit, and we all got clean. Which was key, I think, in building loyalty to Jimmie Jones, even if he didn’t have much to do with it, like I said before. Larry Schacht was a die-hard Jones fan. [Laughs] He die very hard. Me, I didn’t get sent to no med school in Mexico. Jimmie didn’t see no MD in ol’ Watts’ future, figure that. Rufus neither. Larry Schacht was a Jew, like a lot of those white people in the Circle. Like the brother and sister Tropp and that crazy Stein family. Anyway, I guess the good college boy fell off his path to doctorland into a patch of Mary Jane, and from there it wasn’t but a hop and a skip until the habit riding his back in the streets with people like me. I didn’t know him before the Temple, you understand. I’m just guessing. Anyway, after he got off of dope, Jimmie Jones sent him to med school. The King used to brag how the governor of California got behind his application because Dad – yeah, he called him Dad – was so insistent. He just worshipped that dude’s ass. And I mean literally, because they did the nasty together on many occasions, and not always in private. Ol’ Jimmie Jones, who pride himself on being the only “true heterosexual” in Peoples Temple – those his words – he seriously into getting some dick whenever he could. Pardon my language. So if Jimmie say jump, King Doper say not only “how high?” but “Can I get you anything while I’m up there?” He used to tell Rufus and me dope stories, like addicts do, you know, from the bad ol’, good ol’ days – you knew he was getting off on the memory – and still craved the dope. He didn’t do it anymore, understand, but man he loved to dole it out. ’Specially to Jimmie Jones, who sample every medication ever prescribed in the Western World. He flyin’ seriously high above our heads on speed since Day One, which was clear as glass to people like me. “He has so much energy, does the Reverend,” the white chick circle always saying. “Isn’t he amazing!” Hah. He have the audacity to say he wear those sunglasses all the time ’cause he worry he could hurt someone with the intensity of his eyes. No shit. Probably the most creative excuse in history for bloodshot eyes, but the Circle didn’t want to see it till the end, and even then, some of them refused to believe dear ol’ Dad was just another doper like Rufus and me. The black bottom of the Peoples Temple. The base. The place he got all that Social Security money and collection money from to run the operation – poor old black ladies giving him their last dollars and the ratty houses they saved for all their lives because so-called Dad healed some auntie of cancer or cataracts. Of course those healings all fake. Some people – most people, I guess – believe whatever they want to be true. Not ol’ Watts. But in a way, that’s what the black folk in the base and the rich white people up in the Circle had in common – they all wanted Dad to be God. For Dad to answer every question they ever had. Me, I never had a father, and I sure wasn’t taking on some white preacher to be my pretend Dad. [Sighs] Just about kill me, this ancient black man at Jonestown – he a hundred years old, at least – calling Jimmie Jones “Daddy” when he young enough to be his grandbaby.

KR: What do you think accounts for Reverend Jones’s success – perhaps that’s a strange word to use – maybe I should rather say his ability to convince so many people to stay with him, and in the end, to take their own lives? In all the similar events that have happened since – in Waco, for instance, or Heaven’s Gate here in California – we’re talking about a few dozen people. In Jonestown, we’re talking nearly a thousand.

WF: Nine-hundred-nine at Jonestown, four in Georgetown. Even though he pumping up the numbers all the time – he say he have thirty thousand members in California, a million in the US to impress the Guyanese – it way too many human beings. [Sighs again] If I knew the answer to that question, I probably be lecturing at some university, like that asshole lawyer, you know who I mean, who make all this money off every conspiracy theory from Abe Lincoln to JFK to MLK Junior. I know they still people think the CIA did it. Maybe there was CIA down in Guyana. Why not? They everyplace else in the world, and sure fucked up Chile pretty good. They probably in downtown Georgetown drinking Demerara with the Embassy guys – or maybe they are the Embassy guys – but how they gonna make all those people drink poison? Don’t make sense. No. I was there. It the people who stayed behind in the States that keep wanting to believe Jimmie Jones some kind of wronged god, some kind of crucified Christ figure or shit like that. Just like he want them to. He say he the reincarnated Christ, or Lenin, or Buddha, or some other leader he think impress people. He think the Soviet Union admire Jimmie Jones and his so-called socialist experiment. White people pretty stupid sometimes.

KR: Do you believe there was racism in the Peoples Temple? I know that about eighty percent of the congregation was black, but as you say, most of the inner circle was white.

WF: Most of Peoples Temple was poor. That most important – the blacks and most of the whites who weren’t in the Circle. So living in Jonestown not so bad compared to the States. For some, it was better. Way better. No crime. No worrying about not having enough cash for groceries or what to cook for the next meal. No dog food for dinner. No being afraid of not having money for the doctor when you need one. Or the dentist. Everything taken care of. That especially good for the old people. If my grandma had lived, she be on that plane to Guyana in about five minutes flat – she clear outta Watts for good. You know that Congressman Ryan, he say Friday night, before it all went down, he say something like, “I know that for some of you people, this is the best thing that ever happened to you.” And everyone cheer like crazy, ’specially the old black folk. They not cheering ’cause Jimmie Jones tell them to. That applause a hundred percent real. But the rich white folk in the Circle – and I mean the lawyers and the nurses and the PR types – they not in Jonestown ’cause they lives so awful back home. They there to change the world. They there ’cause they think Jimmie Jones the second coming of Marx and Che, Lumumba and Mao combined. He the white Leftist wet dream. So yeah, there racism in Peoples Temple. Like the Supreme Court, you know, white people making the laws for everybody else. Sometimes they let in a token or two. What that line? The exception prove the rule. Archie Ijames in the Circle for a while. Yolonda for a little bit. But them black folk didn’t last. They too smart. Yolonda one of the very smart ones got away from Jonestown practically the day she arrive. And Archie – he dead now – Archie with Jimmie Jones from the start in Indiana; he didn’t like Jonestown neither. Tried to quit the Temple, but Jimmie Jones knew that wouldn’t look good, not to have even one black in the higher ups. Even if it only on paper. So he send Archie and his old lady back to the States. They very happy to go, too. No question Peoples Temple racist, like every other institution. You know one that ain’t? But in Jonestown, I mean before it went bad, we having a pretty good time, the black folk and the white folk too. I mean, the white people not in the Circle. It beautiful in Guyana. The colors. The birds. Super-colorful sunsets every night. Me up and sober seeing sunrises every morning. Even the rain felt good.

KR: Do you miss it? Have you ever been back?

WF: I had a wife there. [Long pause]

KR: I’m sorry; I didn’t know.

WF: Yeah. I don’t talk about her much. Think about her every day though. Sometimes every minute, seems like. She and our baby the first to die. She volunteer. Can you figure that? She volunteer to kill the child and then herself after Jimmie Jones say babies go first, ’cause we don’t want the enemy – whoever the fuck it was on that particular day – to be torturing the children. Shit.

KR: I’m so sorry, Watts. I didn’t know you had a wife or a child there. I don’t believe I’ve read that anywhere. Do you want to take a break? Should I turn off the tape?

WF: Nah. I want to talk about her. About them. You know I done a lot of interviews over the years – all the big anniversaries, the media look up ol’ Watts. One-year, five-year, ten-year, twenty-five-year silver anniversary – ain’t so many of us anymore, not the ones who in Jonestown, November 18th, 1978, anyway, and live to tell about it. You look up Robert or DeeDee? Almost nobody talk to them, they nine smart black people left that morning; they see what’s coming down and they hightail it out of there, right through that nasty scary jungle Jimmie Jones and Mac warning us about every five minutes. They say, “We going on a picnic, Dad,” and they gone. I guess since none of them seen the massacre go down, like me, the media not interested in them. But they smarter than me. Mostly parents and their kids. Not like the mother of my kid.

KR: Watts, would you mind talking about her?

WF: Sure. I can talk about her.

KR: What was her name?

WF: She go by Earlene. Earlene Jones. No relation to Jimmie. She from Indiana originally, one of them kids who grew up in the Temple. You wanna talk about brainwashing? Well, the little kids who joined with their parents, sometimes grandparents, they didn’t know no other life. Her mother there, three brothers, two aunties, a few cousins. Her grandpa die over there of a stroke a few months before the end. And the baby. I think it was mine anyway. I don’t know for a fact. That girl so completely different from me. Earlene only eighteen years old. I was twenty-eight. She thought she reform me or something. Make me see the light. Wanted me to shine beside her in the true gospel of Jimmie Jones. Never woulda happened, even if Jonestown still there. Her mama figure me out, try to tell Earlene to keep away from me. But all the same, she like me. I like her. We have some good times. She the only girl ever pregnant with my baby – my body so fucked up – so messed up, I mean. From the dope. I suppose that could be a sign it wasn’t my baby after all, but I just think it was.

KR: How old, then, was the child? If you don’t mind saying.

WF: The baby, she three months old. She one of thirty-three babies born in Jonestown, Guyana. We name her Cassava, ’cause we eat so many of them, and they good, and it a pretty name. ’Scuse me. Gotta use the rest room. [Sound of door slamming]

KR: We’re going to take a break now. Mr. Freeman has disclosed that not only did he lose his wife, but also his child, and that the mother and baby were the first to swallow poison. Apparently, his wife volunteered. I believe this is a scoop for KBBA.

BLACK PEOPLE HAVE BEEN

TREATED LIKE DOGS

BECAUSE OF THE COLOR OF THEIR SKIN.

JEWS WERE MURDERED, AND THEY’RE SUPPOSED TO BE THE CHOSEN PEOPLE OF GOD, OF THE SKY GOD.

THERE IS NO SKY GOD.

BUT I AM THE EARTH GOD.

Jim Jones

Six Weeks Before the End

October 2, 1978

“On behalf of the USSR, our deepest and most sincere greetings to the people of the first socialistic and communistic community from the United States of America in Guyana and in the world.”

Soviet Consul Feodor Timofeyev stepped back from the microphone to bow, as the nearly one thousand people crowded into and around the Pavilion screamed with approval, applauding for several minutes.

From his seat at the VIP table near the front, Virgil Nascimento looked into Nancy Levine’s eyes to gauge her reaction. Like all the ardent Jones devotees, she glowed. Her smile radiated bliss, her satisfaction that years of struggle were today being rewarded in the Soviet diplomat’s tribute. Her brown eyes gleamed, her long, dark hair, adorned with shiny barrettes, glittered under the lights. Here in the jungle, the Soviet satellite named Jonestown was thriving, the Agricultural Mission of the Peoples Temple an internationally acknowledged success. Enraptured, Nancy didn’t even remember to acknowledge Virgil, he thought, as her gaze went from Timofeyev to Jones and back, as if she were watching a championship match back in her hometown of Forest Hills, New York. She looks at Jones like a lover, Virgil thought, and Timofeyev too. For all he knew, she might have slept with the Soviet as well, his whoring mistress to Georgetown’s petty political brokers.

Jones then motioned the crowd to silence and stepped to the podium, embracing Timofeyev before speaking.

“For many years, we’ve made our sympathies publicly known. The United States is not our mother. The USSR is our spiritual motherland.”

Again, the applause was deafening under the metal roof as a sudden splatter of hard rain added to the crowd’s appreciation with bullet-like staccato. Virgil was the master of the diplomatic smile, but beneath the veneer his anger was mounting, his pulse accelerating. Nancy was so many people. A different self in every setting, for every occasion. He was only one. The man he had primed himself to be for a lifetime, with two Mercedes in two Georgetowns, two tasteful homes, two attractive mistresses. Only offspring were lacking. But not for long, he hoped. Last night, his American Jewess had announced in bed that her period was late, and this news reinforced his virility and desire for her. He liked her mouth best of all. She had a talent for using it, but that was not going to result in his own personal empire of Georgetown Guyanese bi-continental progeny. His Guyanese wife had failed in that respect. No child of theirs over the decades had ever survived her womb. But with Nancy, who was twenty years younger than either of them, he could fulfill that dream.

Somewhere in the crowd was the black American baby Nancy had adopted with her American husband, one of the handful of emasculated blond boy-men who trembled in Jones’s wake as if experiencing orgasm solely from proximity to the Great Man himself. Not unlike Nancy, he mused. He watched her wipe her eyes and hug Sharon Amos beside her, who was crying openly, murmuring something. Was she saying, “I love you, I love you” to Jones, who wasn’t looking her way? Or to Timofeyev, whose eyes were taking in the vast, adoring crowd? Had that Amos cow slept with the ambassador? Long ago, Nancy had confided to Virgil that Jones told Nancy he would never sleep with Sharon on principle, that he coerced her extraordinary energy by holding out on her while simultaneously hinting that glorious lovemaking was somewhere down the road of their future, after every single member of the Temple had reached the Promised Land, and the first stage of their revolutionary struggle to build a paradise in Guyana had come to an end.

“Ambassador Timofeyev,” said Jones, cutting into the applause, which instantly ceased. “We are not mistaken in allying our purpose and our destiny with the destiny of the Soviet Union.”

The two men shook hands, then embraced, sparking a mass of embraces throughout the crowd. Virgil wondered if Timofeyev believed anything Jones said. Did Jones believe any of it himself? Did the Soviets really want their destiny linked to that of Jones and his Jonestown Jerusalem? Wasn’t Jones too self-interested to be a good fit with the USSR?

The next time Virgil looked to Nancy to gauge her current state of Jones-adulation, her seat across the table was empty. Where had she disappeared to? Virgil did not trust her. Was she looking for her white boy to share the joy? Why had she left him alone? Beside him was the Soviet ambassador’s aide. Virgil didn’t have a full-time aide. It rankled. Timofeyev had had one for years, but the illustrious Guyanese Ambassador to the United States was always without an attendant whenever he was in his natal country. On his other side was Marceline Jones. She did not appear to be trembling at the edge of rapture like Sharon and Nancy. Instead, she was biting her lip. Still, she clapped along with the others. Noticing Virgil’s attention, she quickly smiled at him.

“Ambassador Nascimento, we’re so very pleased you were able to be here today. As you can see, it’s a big, important moment for our church.”

Adjusting his tie, Virgil smiled back and thanked her for the invitation. Always he had wondered about her, the woman behind this extraordinary man, though he personally despised Jones for having slept with Nancy prior to his own meeting with his modern Mata Hari. How did this kindly, motherly woman, she with her enormous “rainbow family” of adopted children, now a grandmother, manage to ignore her husband generously dispersing his sperm among the luscious young women in his circle of secretaries, administrators, and financial officers? True, she had conceived one child with Jones before he began his out-of-wedlock family – the teenaged Marcus, glowering on his mother’s right, a carbon copy of Jones but without the bravado.

“You have always been a great friend to us, Ambassador Nascimento, notwithstanding my husband’s remark just now about the United States.” She winked.

“Of course, my mother country is not yours,” he said, pretending to go along with his hostess’s intimation that indeed the Soviet Union could offer their group more than the United States. And he didn’t believe for a moment that the Peoples Temple would ever re-locate to the cold, barren landscape of Russia, though the Peoples Temple officers in the capital were always giving lip service to it, including Nancy of course, waxing poetic over Russian literature and music. She kept a Russian grammar by their bed in the Guyanese Georgetown and liked to conjugate verbs first thing upon waking, as if to impress him.

The crowd was mostly black, a majority with roots in the humid American South. They were so comfortable here in the jungle, and Virgil couldn’t possibly imagine them living in the Baltic region. Apparently some “warm” spot by the Black Sea had been scouted out already for their future home. Jones was lying about the balmy weather to his people. The Soviet Union had no place for a Peoples Temple, with its leader-idol and legions of idolaters.

Months ago, he’d overheard Timofeyev at a cocktail party telling someone that the Peoples Temple’s love for the Soviet Union was entirely unrequited. It was true. The Soviets would never want someone like Jones in their midst, a figure who would only interfere with their particular version of hero worship which extended even beyond the grave: Lenin’s tomb and its long line of necrophiliacs waiting to show their obeisance. Virgil winced, remembering his Moscow visit decades earlier, the pallid lighting of the corpse’s face, the widows’ tears streaking the glass coffin cover.

“As you know, Ambassador, we’re in love with your mother country,” Marceline said, gesturing toward the greenheart trees surrounding them, their outlines fading in the dusk as the fluorescent lights of the pavilion illuminated hundreds of faces, black and white, grinning and gleeful, around their table. Marcus Jones’s arms were folded tightly across his chest as he listened to his mother. It was hard to discern the meaning of the smirk on his face. Was Marceline being ironic? Did the boy agree with her? Did he wish to be excluded from that we?

“Ambassador Nascimento, I’d like you to meet my daughter, Quiana,” said Nancy, suddenly appearing behind him. He swiveled as she materialized out of the dense crowd of bodies, her arms around a little black baby, a girl with no hair and a huge toothless smile. Virgil squeezed the baby’s hand.

“Pleased to meet you, Quiana.” Even to his own ears, Virgil’s voice rang horribly false. He knew that Nancy knew his pretend pleasure was all show for Marceline. Virgil wasn’t interested in Nancy’s adopted daughter and didn’t adore adoption the way Peoples Temple members did. Virgil wanted his own blood to represent him in posterity, not someone else’s. He had tried to make pure Guyanese progeny and failed. Now he would make Guyanese-American babies. Nancy would forget about this Quiana when she had her own child.

“It is a great pleasure,” interrupted the heavily accented English of Timofeyev over the loudspeaker, “to see how happy you are being in a free society which you built with your own hands, developed with your own hands. I am very happy that I saw here in Jonestown the full harmony of theory which have been created by Marx, Engels, Lenin, and the practical implementation of this—some fundamental features of this theory, under the leadership or together with you, by Comrade Jim Jones, and I’d like to thank him for that.”

Roaring applause again, which Virgil joined. He clapped like a European. Tastefully, without calling attention to himself. Not like the Americans.

In San Francisco, Truth was listening to the speech over the short-wave radio. She too was weeping, but her joy was leavened with the frustration of not being there in person to listen to the Soviet ambassador, whom the Temple had been courting for years. Finally, they had succeeded in their quest to bring him to Jonestown, along with the doctor, Nicolai, who had praised their clinic as the best of its kind in any developing nation, Marxist or Capitalist. For months, Truth had been involved with Stateside planning for this, locating primers in Russian for the Temple population and shipping them overseas, ferreting out recordings of Russian songs the group could sing to the ambassador. She had been studying Russian too. Whenever she could. In her spare moments over meals or before bed, humming in the shower. “We are communists today and we’re communists all the way. Oh, we’re communists today and we’re glad.”

Whenever the group applauded, her headphones shrieked. Tonight there had been so much applause that Truth was holding the bulky contraption beside and above her ears rather than on them. She had noticed that her formerly excellent hearing was deteriorating from so much radio work.

“Hey Truth. My turn!” Ida said, coming into the room. “You been hogging those headphones for an hour, girl!”

Without a word, Truth handed them over. It was true. She ought to be sharing. Although the speech was being recorded, their broadcasting technology in the San Francisco temple had failed, so they were unable to play the speech over the PA system. Only one person at a time could hear the words live, as they were being uttered at the Pavilion in the jungle, with only a thirty-second delay before they entered the ears of the listener thousands of miles away in the Peoples Temple’s last remaining home in the United States.

Truth rose to stretch her legs, walked down the hall and back. It wasn’t fair. Ida had been to Jonestown twice already while Truth had been stuck in the Bay Area the entire time, wanting desperately to join the rest of her chosen family in the Promised Land. But whenever she brought the subject up with Jim, he chided her for selfishness.

“Truth, honey, we got twelve hundred people here who need. Do you understand what I’m saying? They need me for strength, they need me for discipline, they need me for love, they need me for food. It takes a hell of a lot out of me every damn day, you understand?” He had repeated this speech, with variations, every month or so when she brought it up on the phone. “So don’t complain to me about where you are right now. I need you there, and the Temple needs you there, you and the rest of the good people still in the city. You’re making what we have here possible, and as soon as I can, I’ll send for you. End of discussion. You know I love you, honey.”

Did she know? Did he really love her?

Up and down the hall she paced, looking in on the empty rooms where once staff had lived, in bunk beds two or three or even four to a room, sharing the communal bathrooms as if it were some cramped college dormitory. Truth had begun and quit college so fast she barely recalled her days in a real dorm. Mostly she remembered the unbearable loneliness, how estranged she felt from all the beautiful blond people with their California tans and tales of vacations in Hawaii and Mexico. For a New Jersey girl who’d never even been on a plane before her trip to San Francisco just after her eighteenth birthday, the isolation of her skyscraper dormitory beside Lake Merced was brutal. Her roommate, Patience, made fun of her accent. Not with malice, but the girl’s teasing made her feel like a clod. Uncomfortable and out of place in the world. This was a sensation Truth had lived with most of her life. Patience was from a place called Grass Valley, and of course everyone joked about the name of her hometown, puffing pretend joints whenever they said it. But Patience had taken it all in stride, laughing as she expertly rolled her daily doobies, a supply from her boyfriend back home that never seemed to quit.

“Truth?” Ida was calling her. “Something’s not right here; it keeps squawking in my ears. I’m getting an earache.”

Truth told herself that if she really were a good person, she would explain to Ida how to lessen the impact, how to finesse the temperamental dials, but really, she wanted Ida to hand the headphones back over, so she shrugged and said, “It’s hard on the ears, but oh well.”

Ida frowned and shook her head. “You something else, Truth. Here. I know you dying to put ’em back on your head.” She rolled her eyes at Truth, a familiar gesture, as if to say, “Crazy Truth, there you go being weird again.” Before she had joined the Temple, it had been “Crazy Lizzie,” or “Wacko Elizabeth.”

Taking the headphones, Truth went back inside the radio room, shutting the door carefully behind her, wishing it would lock, but nothing locked in the Temple, except for wherever money was stored. Jim said it wasn’t to hide from his own people. He trusted them implicitly, he swore. It was from outsiders, their enemies, and the ever-present traitors. At first, Truth hadn’t believed in the idea that those who left the Temple would harm those who remained, but time after time, Jim offered proof of the traitors’ vindictive intentions, resulting, finally, in the disastrous New West article last year, in which nearly a dozen former members uttered hideous lies about Jim and the Temple, prompting the massive exodus to Jonestown. “People lie,” Jim always said. “The press prefers lies to truth.” Like a mantra, he repeated it so often that Truth believed it. Just as she believed in Jim, without reservation or doubt.

When she put the headphones back on, she heard Deanna Wilkinson singing “The Internationale.” God, that woman could sing. Truth couldn’t. Not a note. “Tone stone deaf,” her elementary music instructor had pronounced when ten-year-old Elizabeth had tried to play the clarinet. Listening to Deanna’s beautiful voice, the tears began to fall, the lyrics eliciting Truth’s yearning for a better world, one without suffering or cruel teachers. A kinder, better world awaited her in Guyana.

This time the Soviet ambassador’s voice came through without squawking.

“Lenin, when he addressed the youth, he said, ‘Comrades, your first task is to study, study, and again, to study, how to build the socialism, how to build the communism.’ So our young people, our old people, our middle generation, our teenagers, everybody knows the importance of the knowledge. Because only through the knowledge, through the understanding of the international processes, through the understanding of theory of communism, of the Marxist-Leninist philosophy, of political economy, and some other subjects, you can really become the communist, you can really build the society which is free of exploitation, free of any form of racial or any other discrimination, because you should know the theory, how to build. But not only know it but implement it practically and daily in your life.”

Yes, Truth said to herself. The words energized her and pushed her away from her own petty failures. That was indeed what she needed to do more of: to study. To educate herself. Not to hang her knowledge out of some ivory tower window for show, but to use it every day, on the street, with the people, in the bush. If only she could get to the bush. Why Ida but not her?

Tears rose again, and she willed them back down. She could picture Jonestown, the scene at the Pavilion. She had pored over so many photographs of their revolutionary agricultural mission. Recently, a member had shot a blurry film of the latest harvest, full of black and white people waving at the camera, happy to be plucking cassavas and eddoes they had planted and sown themselves. Just like Timofeyev had said: With their own hands, they had grown this life, nurtured it into being. A miracle? No, the hard work of all those bodies out in the fields. She desperately wanted to be one of them, to sweat her dedication into the soil that would in turn produce their food. But not yet, not now, Jim had said. For now, her work was here, in the tilling of papers, the harvesting of positive PR, getting the Feds off the backs of the Peoples Temple in Guyana. Truth had been part of the successful effort against Social Security, who had stopped the elders’ funds for a few months, believing the Temple administrators were keeping the old folks’ money from them against their will. Without that money, the commune could barely function, but now the paperwork had been reinstated and checks were flowing as before. Jim had praised her for her part. It was small consolation compared to the glory of being part of that jungle dream. She reminded herself that Revolution is slow, full of missteps and mistakes, but at least there was one thing she’d done absolutely right.

Once, just after Jim made Exodus, he said he was thinking of sending Truth to DC to lobby for the Temple. Awed by the prospect of such responsibility, she had meekly told him that she didn’t know if she was up to such a task. Someone better-looking and more articulate – a woman and not a man would be chosen for the job, it was clear but never stated – might be a better choice. Jocelyn, obviously, or Maria. Of course Marceline was first choice, but she was needed in so many places in so many different capacities that she wasn’t always available for travel. Better a woman without children.

“You’re right, Truth,” Jim had said in response to her half-hearted objections. “You’re always so accurate in your self-assessments. I’ve always admired that about you. I’ll send Jocelyn. Thank you.”

Devastated, she’d cried after ending their radio connection. Really, Truth hadn’t meant to disqualify herself. She’d only meant to be humble, as Jim was always preaching. Humility was important, especially for white people. She would have done a spectacular job, Truth thought. She would have acquired some conservative-looking clothes at a quality thrift shop, had her hair cut, maybe lost some weight ahead of time. But she’d never be Jocelyn, bright and poised and pretty and brilliant. Jocelyn had a degree in French literature or something. She wasn’t a dropout like Truth.

After a lot of static, she heard Timofeyev again: “I wish you, again and again, all the successes in your work, in your difficult task, to build the socialism, to build the communism. Thank you very much.”

Applause again, deafening, screeching, scraping her tender eardrums. Abruptly, she removed the headphones and opened the door to look for Ida.

“Ida? The ambassador just said goodbye. I’m exhausted. You want to listen now?”

Arriving at the door with two steaming Styrofoam cups, Ida said, “Sure I do. Brought you some coffee. Want some?”

Shaking her head, Truth said she was going to sleep.

“More for me then.” Ida gave her a warm hug. “I’ll stay up and monitor for a couple hours. You crash, sister. You need it.”

Timofeyev had returned to the table and was speaking Russian to his assistant. Virgil watched their easy communication, the obvious authority Timofeyev had over the younger man, who had his notebook out, taking directions swiftly and without backtalk. Nicolai, the Russian doctor, had joined them and their conversation was spirited following an obviously successful speech. Once, Virgil had been fairly conversant in Russian after his six months in the Soviet Union during his Oxford days, but the intervening years and his immersion in English had displaced that vocabulary.

Timofeyev accepted Virgil’s outstretched hand and shook it with vigor.

“Karashaw, tovarich,” Virgil said loudly, “Ochen karashaw.”

Sure that Nancy would be impressed with his Russian, Virgil searched for her, but she and the child had gone off again. He wanted her beside him. Not in his arms – they didn’t do that in public – but next to him, so that he could feel her presence, her sex, that Americanness inside her he had come to possess during the last few years, that idea of possession more and more important as he aged. Yes, she would produce a baby. His baby, one of many. Prudence was too old now. Besides, her life was in London now. She had no room for children.

“Feodor, I must compliment you on your English.”

Timofeyev looked gratified. “Spaciba, Comrade Nascimento. Spaciba.”

After a few more words with Nicolai and the assistant, Timofeyev tapped Virgil’s arm. “Are you flying back with us to capital this evening? Or staying here, in this utopian exemplar?”

There was a touch of sarcasm in Timofeyev’s tone. Utopian exemplar. Where had he heard that phrase? Did he mean it sincerely? Perhaps, like Virgil himself, Timofeyev knew how to talk the appropriate talk but personally believed none of it. Virgil had seen the Muscovite’s home in Lamaha Gardens. One of Georgetown’s nicest, as grand and finely appointed as the Prime Minister’s. Communism was fine for the masses, as long as you weren’t one of them.

“As soon as I find Miss Levine, we will be joining you.”

After surveying the encroaching darkness, the blackening edges of the greenheart canopy, Timofeyev said, “We must go now if we are to get out before night falls.”

Evidently, Marceline Jones was thinking the same, as she arrived to usher the ambassadors toward the tractor that would transport them the several miles to the airstrip in Port Kaituma.

“I apologize for the primitive condition of our vehicle,” she said, pointing to the huge, mud-caked wheels, “but one day, down the road, we’ll have better.”

Timofeyev insisted that the tractor was perfect, the ultimate rural proletarian vehicle. Virgil fulsomely agreed, though he would much rather be in the Guyanese constable’s jeep which at least had shock absorbers, and an intact roof.

Where was Nancy?

As Virgil and the three Russians crammed into the open cab of the tractor, the driver said, “Hang on, das svedana.” Marceline looked back for Nancy, who was evidently not coming. Reverend Jones’s wife was too discreet to say anything aloud, but she knew, like the rest of them, that Nancy was expected by Virgil to accompany him back to Georgetown.

“I believe Quiana had a fever,” Marceline said. “I’m sure Nancy will get back to Georgetown as soon as her daughter’s better. You should go now, before the light does.”

The driver of the tractor introduced himself in Russian. “Ya loobloo Watts.” That’s what it sounded like to Virgil, who translated the man’s sentence as “I love Watts,” an American slum famous for burning itself down in protest back in the sixties. Virgil had never quite understood the impulse to destroy one’s own habitat to épater les bourgeois, but he understood that African Americans of all backgrounds shared the view that skin color was all.

The Ambassador responded in a happy stream of Russian words, but the driver said, “Da, da. Whatever. I gotta concentrate on driving now.” He turned the tractor around and shortly they were heading back up the hole-pocked lane, everyone hanging onto whatever part of the vehicle they could so as not to fall into the mud. The young man had a massive Afro and a muscular build, and he drove fast, far too fast for the condition of the road, but Virgil knew that the pilot wouldn’t wait much longer, and then they’d have to bed down either in the village, which had no hotel, or back in Jonestown, which was far too uncivilized for Virgil’s taste. The Soviets evidently felt the same, as he heard the assistant telling the driver, “Hurry, please. We must not miss this plane.”

“I’m going as fast as I can, Comrade Tovarich.” The fastest he could drive on a road like that in a beat-up tractor was five miles an hour. At that rate, they’d never make it.

Suddenly, the driver braked hard, almost tossing Dr. Nicolai onto the road, but Virgil caught him in time. Why were they stopping?

Running swiftly, running as only an energized very young person could, Nancy appeared beside the vehicle. “Thanks, Watts,” she said, giving him her megawatt smile.

Virgil was conflicted. He was gratified that she had made it but was jealous of that smile. He grunted a hello. She held on to one of the upright supports beside him. As the Soviets were deep in conversation, pausing only to ask the driver to go “Faster! Fastest!” Virgil allowed himself to be caressed by his mistress. Nancy’s hand boldly reached beneath his suit jacket, cupping him through his trousers. Did the driver wink at him? No, he must be squinting due to the waning daylight, the difficulty in seeing the road clearly.

“It went really well, don’t you think?” Nancy whispered as she rubbed him. “I’m so happy. I think Jim is too. I haven’t seen him smile like that in a long time.” She laughed with relief. Her face was flushed, and she seemed high to Virgil, though he knew it wasn’t anything chemical.

Jim was more a father figure than a love and sex object for her. Virgil frowned with distaste when he considered he was the same age as Jones. She was always trying to please her leader in the way children do their parents, frantic that he be proud of her efforts, of how hard she had worked. Bagging Virgil must have netted her an A+. But she didn’t seem to harbor the same fatherly feelings for Virgil.

“What’s the difference, in the end?” Virgil whispered back, enjoying her hand’s steady rhythm. “You’re not moving to the USSR, are you?”

Immediately, she stopped her ministrations. “If Jim wants me to, I’ll go.” Although he couldn’t see her face clearly, Virgil knew she was frowning at him, as if he had no right to expect loyalty from her.

“What about the girl? Is she all right?”

“What are you talking about? Quiana’s fine.”

Mrs. Jones must have invented the fever just to cover for Nancy in case she didn’t show. Virgil sighed, wishing his attempt at concern would elicit Nancy’s continued caresses, but he remained as before, yearning.

The driver was humming that idiotic Communist song Jones had sung to Timofeyev over and over, solo and in chorus, as if Timofeyev actually enjoyed hearing it. “Oh, we are communists today and I’m glad. We are communists today and we’re glad. Yes, we are communist today; we are communist all the way. We are communist today and we’re glad.”