14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

The darker side of the Parisian Left Bank in the 1940s , with supernatural elements.

Das E-Book wird angeboten von und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Jacques Yonnet

Paris Noir

The Secret History of a City

translated with an introduction and notes by Christine Donougher

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited, 24-26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

Email: info@ dedalusbooks.com

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN printed book 978 1 903517 48 2

ISBN e-book 978 1 907650 36 9

Dedalus is distributed in the USA and Canada by SCB Distributors, 15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

email: [email protected] web: www.scbdistributors.com

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd.

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W. 2080

email: [email protected]

Publishing History

First published in France in 1954

First published by Dedalus in 2006, reprinted in 2009

First e-book edition 2011

Rue des Maléfices © copyright Editions Phébus, Paris 1987

Introduction, notes and translation © copyright Christine Donougher 2006

The right of the estate of Jacques Yonnet to be identified as the copyright holder and Christine Donougher to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988

Printed in Finland by WS.Bookwell

Typeset by Refine Catch Ltd, Bungay, Suffolk

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A C.I.P. listing for this book is available on request.

THE TRANSLATOR

Christine Donougher’s translation of The Book of Nights won the 1992 Scott Moncrieff Translation Prize.

Her translations from French for Dedalus are: 6 novels by Sylvie Germain‚ The Book of Nights‚ Night of Amber‚ Days of Anger‚ The Book of Tobias‚ Invitation to a Journey and The Song of False Lovers‚ Enigma by Rezvani‚ The Experience of the Night by Marcel Béalu‚ Le Calvaire by Octave Mirbeau‚ Tales from the Saragossa Manuscript by Jan Potocki‚ The Land of Darkness by Daniel Arsand and Paris Noir by Jacques Yonnet.

Her translation from Italian for Dedalus are Senso (and other stories) by Camillo Boito‚ Sparrow and Temptation (and other stories) by Giovanni Verga.

Christine Donougher is currently translating Magnus by Sylvie Germain for Dedalus.

French Literature from Dedalus

French Language Literature in translation is an important part of Dedalus’s list‚ with French being the language par excellence of literary fantasy.

The Land of Darkness – Daniel Arsand £8.99

Séraphita – Balzac £6.99

The Quest of the Absolute – Balzac £6.99

The Experience of the Night – Marcel Béalu £8.99

Episodes of Vathek – Beckford £6.99

The Devil in Love – Jacques Cazotte £5.99

Les Diaboliques – Barbey D’Aurevilly £7.99

Milagrosa – Mercedes Deambrosis £8.99

An Afternoon with Rock Hudson – Mercedes Deambrosis £6.99

The Man in Flames – Serge Filippini £10.99

Spirite (and Coffee Pot) – Théophile Gautier £6.99

Angels of Perversity – Rémy de Gourmont £6.99

The Book of Nights – Sylvie Germain £8.99

The Book of Tobias – Sylvie Germain £7.99

Night of Amber – Sylvie Germain £8.99

Days of Anger – Sylvie Germain £8.99

The Medusa Child – Sylvie Germain £8.99

The Weeping Woman – Sylvie Germain £6.99

Infinite Possibilities – Sylvie Germain £8.99

Invitation to a Journey – Sylvie Germain £7.99

The Song of False Lovers – Sylvie Germain £8.99

Parisian Sketches – J.K. Huysmans £6.99

Marthe – J.K. Huysmans £6.99

Là-Bas – J.K. Huysmans £8.99

En Route – J.K. Huysmans £7.99

The Cathedral – J.K. Huysmans £7.99

The Oblate of St Benedict – J.K. Huysmans £7.99

Lobster – Guillaume Lecasble £6.99

The Mystery of the Yellow Room – Gaston Leroux £7.99

The Perfume of the Lady in Black – Gaston Leroux £8.99

Monsieur de Phocas – Jean Lorrain £8.99

The Woman and the Puppet – Pierre l ouÿs £6.99

Portrait of an Englishman in his Chateau – Pieyre de Mandiargues £7.99

Abbé Jules – Octave Mirbeau £8.99

Le Calvaire – Octave Mirbeau £7.99

The Diary of a Chambermaid – Octave Mirbeau £7.99

Sébastien Roch – Octave Mirbeau £9.99

Torture Garden – Octave Mirbeau £7.99

Smarra & Trilby – Charles Nodier £6.99

Manon Lescaut – Abbé Prévost £7.99

Tales from the Saragossa Manuscript – Jan Potocki £5.99

Monsieur Venus – Rachilde £6.99

The Marquise de Sade – Rachilde £8.99

Enigma – Rezvani £8.99

Paris Noir – Jacques Yonnet £9.99

Micromegas – Voltaire £4.95

Anthologies featuring French Literature in translation:

The Dedalus Book of French Horror: the 19c – ed T. Hale £9.99

The Dedalus Book of Decadence – ed Brian Stableford £7.99

The Dedalus Book of Surrealism – ed Michael Richardson £9.99

Myth of the World: Surrealism 2 – ed Michael Richardson £9.99

The Dedalus Book of Medieval Literature – ed Brian Murdoch £9.99

The Dedalus Book of Sexual Ambiguity – ed Emma Wilson £8.99

The Decadent Cookbook – Medlar Lucan & Durian Gray £9.99

The Decadent Gardener – Medlar Lucan & Durian Gray £9.99

Contents

Translator’s Introduction

Chapter I

The Watchmaker of Backward-Running Time

Chapter II

The Man Who Repented of Betraying a Secret

The Shipwreckage Doll

Chapter III

‘Your Body’s Tattooed’

Enemy Tattoos

The House That No Longer Exists

Chapter IV

Alfophonse’s Moniker

The Sorry Tale of Théophile Trigou

The Ill-Fated Knees

The Old Man Who Appears After Midnight

The Ill-Fated Knees

Chapter V

Mina the Cat

Chapter VI

Keep-on-Dancin’

Chapter VII

St Patère

The ‘Bohemians’ and Paris

Zoltan the Mastermind

The Old Man Who Appears After Midnight

Chapter VIII

Rue des Maléfices

Chapter IX

The Sleeper on the Pont-au-Double

Keep-on-Dancin’

The Sleeper on the Pont-au-Double

Chapter X

The Sleeper on the Pont-au-Double

Chapter XI

Marionettes and Magic Spells

The Old Man Who Appears After Midnight

Zoltan the Mastermind

The Old Man Who Appears After Midnight

Chapter XII

On the Art of Accommodating the Dead

Keep-on-Dancin’

Zoltan the Mastermind

Chapter XIII

The Gypsies of Paris

The St-Médard Concessions

The Gypsies of Paris

Chapter XIV

Keep-on-Dancin’

Chapter XV

The Shipwreckage Doll

Chapter XVI

Rue des Maléfices

Translator’s Notes

Translator’s Introduction

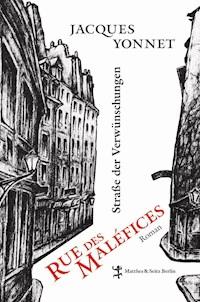

First issued in 1954 under the publisher’s choice of title Enchantements sur Paris (Paris Spellbound)‚ reissued in accordance the author’s wishes as Rue des Maléfices (Witchcraft Street)‚ Jacques Yonnet’s only published book fits into no single category. Personal diary‚ memoir of some of the darkest hours in a nation’s history‚ guide to a city’s lower depths‚ ethnographical study of an urban population that no longer exists or has been driven elsewhere‚ record of a number of paranormal incidents and experiences – Paris Noir is all of these.

Jacques Yonnet is twenty-four years old when war breaks out in 1939. Captured by the Germans in June 1940‚ as France’s eastern defences crumble before the invasion‚ Yonnet escapes and returns to his native city‚ but not to where he is known‚ at home among old friends and family (of socialist inclinations). A hunted man‚ sought by the Nazis and by the collaborationist French police‚ he goes underground in the heart of Paris‚ in the ‘villages’ of the 5th arrondissement on the Left Bank – Maubert‚ Montagne‚ Mouffetard‚ Gobelins. Here he finds refuge‚ as though in another world‚ another dimension.

It is a world that would have been familiar to the great French poet of the 15th century‚ François Villon‚ a world peopled by beggars and rag-pickers‚ mercenary soldiers‚ petty criminals‚ police informers‚ penniless artists‚ whores‚ healers‚ drunks‚ exiles‚ exorcists‚ gypsies‚ wayward wives and defrocked priests. And the common ground on which they all meet are the numerous bars and drinking establishments that offer a curious combination of anonymity and community‚ an ideal environment for a young man who is to become active in the Resistance.

Because as the war progresses‚ Yonnet‚ for all his natural scepticism and non-conformist anarchist tendencies‚ gets involved in clandestine warfare and ends up running a mapping and radio transmission centre‚ liaising with London to ensure that Allied bombings on German targets in the Parisian region are carried out with the fewest possible civilian casualties. But far from being motivated by any notion of patriotism or ideology‚ it is a personal sympathy for the plight of a parachutist in hiding that draws him in. It is the individual story to which he responds.

And this curious world that he now inhabits throws up the most extraordinary individual stories‚ which for Yonnet constitute the real fabric of the city he loves: stories of love and hatred‚ friendship and betrayal‚ obsession and jealousy‚ persecution and revenge – but always with a curious edge to them‚ a suggestion that things could not have happened otherwise‚ at that time‚ in that place.

What emerges from Yonnet’s stories is a sense that it is the city itself that creates its own history. It is not an inanimate construct. It exists on a level that transcends the physical evidence of the here and now. And events are in some mysterious way determined by their location‚ even as the location is defined by the events that have occurred there.

Whilst these are conclusions that Yonnet himself has reached‚ through reflection and observation and extensive reading of historical documents and literature on Paris‚ some of the low-life characters with whom he becomes acquainted – the cool killer Keep-on-Dancin’‚ for instance‚ or the Gypsy who exacts a terrible revenge for being insulted – turn out to be extraordinary repositories of this kind of wisdom about the nature of the city‚ and willing to share their arcane knowledge with him.

Tantalizingly‚ not all of their confidences does he pass on‚ having been sworn to secrecy. For such knowledge is not to be trifled with. It can be a matter of life and death‚ as we see in the story of the shipwreckage doll or the room where nothing but the truth can be spoken. Not that Yonnet makes any attempt to argue a case. That is not his style. He presents himself simply as a witness‚ although Yonnet himself is the protagonist of one of the most thrilling‚ chilling stories of all.

A born raconteur‚ he records with consummate narrative skill‚ an eye for the compelling detail and a finely attuned ear for the raw energy and economical humour of a Parisian argot redolent of its period‚ what he has seen and heard and experienced. In doing so‚ he brings to life a cast of unforgettable characters – from Mina the Cat‚ Cyril the Watchmaker and Poloche the Shrimp-Fisher to Pepe the Pansy‚ Dolly-the- Slow-Burner and the Old Man Who Appears After Midnight‚ to name only a few – and with all the accomplishment of a verbal sorcerer conjures up a Paris that has long since disappeared along with the population that once used to inhabit it.

In translating Yonnet’s book I have tried to capture the flavour of the argot – which sounds dated to contemporary French ears – without resorting to a vocabulary too suggestive of a non-Parisian environment – American or Cockney‚ for instance. I have also appended a few explanatory notes on some of the references in Yonnet’s text that would not necessarily be understood by English readers today.

Christine Donougher

Chapter I

An age-old city is like a pond. With its colours and reflections. Its chills and murk. Its ferment‚ its sorcery‚ its hidden life.

A city is like a woman‚ with a woman’s desires and dislikes. Her abandon and restraint. Her reserve – above all‚ her reserve.

To get to the heart of a city‚ to learn its most subtle secrets‚ takes infinite tenderness‚ and patience sometimes to the point of despair. It calls for an artlessly delicate touch‚ a more or less unconditional love. Over centuries.

Time works for those who place themselves beyond time.

You’re no true Parisian‚ you do not know your city‚ if you haven’t experienced its ghosts. To become imbued with shades of grey‚ to blend into the drab obscurity of blind spots‚ to join the clammy crowd that emerges‚ or seeps‚ at certain times of day from the metros‚ railway stations‚ cinemas or churches‚ to feel a silent and distant brotherhood with the lonely wanderer‚ the dreamer in his shy solitude‚ the crank‚ the beggar‚ even the drunk – all this entails a long and difficult apprenticeship‚ a knowledge of people and places that only years of patient observation can confer.

It is in tumultous times that the true temperament of a city – and even more so‚ of the coagulated mass of sixty villages or so that make up Paris – reveals itself. For thirteen years I’ve been compiling all kinds of notes‚ especially historical‚ for such is my profession. From them I have extracted what relates to a series of events I witnessed‚ or of which I was the very unlikely protagonist. A kind of diffidence‚ of indescribable fear prevented me from bringing this work to fruition before now.

Maybe it is due to particular circumstances that the bizarre events that are the subject of this work struck me as fantastic – but fantastic on a human scale.

I discovered in every fortuitous circumstance‚ weird occurrence and freak of coincidence a logic so rigorous that in my constant concern for truthfulness I felt compelled to introduce myself into the narrative much more than was perhaps strictly necessary. But it was essential to capture the period‚ and this period I lived through‚ more intensely than many others. I was steeped in it to the core. All the same‚ it would never have occurred to me to relate a personal story had I not been aware how intimately related it is to that‚ infinitely more complex and worthy of interest‚ of the City itself.

There are no fictional characters here‚ nor any anecdotes arising solely from the imagination of the narrator – who could just as well be any one else.

So what should be seen in this book then is not the most disquieting but disquieted of testimonies.

1941

Beyond the island and the two branches of the river‚ the city changes. In the square‚ on the site of the old morgue‚ stones dating from different periods that cannot abide each other have been cemented on top of one another. There’s a muted hatred between them. It grieves me as much as it does them. It’s inconceivable that no one gave any thought to this.

The Seine is sulking. Showing the same moodiness as before‚ when I came to pay my respects after a rather longer trip than I would have liked. This river is no easy mistress.

It will be a hard winter. There are already seagulls at La Tournelle‚ and it’s only September.

In June 1940‚ at Boult-sur-Suippe‚ I was wounded and taken prisoner. I found out that the Germans had identified me as a radical journalist. I escaped at the first opportunity.

I have a little money. Enough to survive two weeks‚ perhaps three. But all I have in terms of identity papers is the service record of Sergeant Ybarne‚ a priest with no family‚ who died in my camp – and a demobilization document I concocted for myself.

I don’t know whether it will be possible one day to regain my own family name. I have constantly to beware of patrols and raids‚ especially those carried out by French policemen.

I don’t yet know where to sleep. I’m not without trustworthy friends: a good dozen. I’ve lurked beneath their windows and always thought better of calling on them.

I wandered through the Ghetto‚ behind the Hotel de Ville. I know its every paving stone‚ every brick of every house. I came away disappointed‚ almost angry. There’s an atmosphere of despair‚ acceptance‚ resignation. I wanted to breath a more vigorous air. It was towards Maubert‚ with its secret smile‚ that an overriding instinct guided my steps. I’m drawn to Rue des Grands-Degrés. I’ve just got this feeling I’m sure to shake hands with a friend there.

The Watchmaker of Backward-Running Time

This little green clapboard shed is the ‘shop’ (not quite three square metres in size) of Cyril the master watchmaker. Born in Kiev‚ God knows when.

Old Georgette the washerwoman‚ one of the doyennes of La Maube‚ who remembers the Château-Rouge and Père Lunette and the opening of Rue Lagrange‚ told me in 1938‚ ‘That guy’s incredible. I’m getting on for seventy and I’ve known him for ever. Watchmender with second-hand watches to flog. Never any trouble. Every now and then he changes his name. Says he’s entitled to. That’s the fourteenth woman he’s on to now. He’s buried more than half the rest. And his face still looks the same as ever. I can’t figure it out.’

It was certainly curious. More immediate concerns prevented me from paying much attention to ‘the case’ of Cyril. And then‚ some time later‚ I meet him in a bar and tell him the story (that I’d just pieced together) of the building his shack leans up against.

A colonel in the days of the Empire (when all colonels were courageous) lost a leg at Austerlizt. This led to his retirement. The officer sought permission from the Emperor to return to Paris with his horse‚ with whom he had developed a close friendship. The Emperor was in a good mood that day. Permission was granted.

Colonel and horse bought the house‚ and had an extra storey built on to it. It has a big courtyard paved with sandstone. A huge watering trough was installed in it at great expense. For His Nibs the Horse was in the habit of taking baths and could only drink from running water. The colonel’s assets and pension were insufficient to pay for the three or four fellows who shuttled back and forth with their buckets‚ between the Seine and the sybaritic nag’s intermittently flowing stream. Colonel and mount expired simultaneously‚ locked in each other’s embrace.

Cyril found this highly amusing. We drank a lot and became bosom pals.

Cyril has found me a refuge. He took me to Rue Maître- Albert. A street that dog-legs down to the river. Pignol’s – a low dive – is a tiny place‚ crammed with people. Snacks are served behind closed shutters.

Hourly patrols come storming up the street. Their boots can be heard a long way off. It sounds as though the asphalt answers ‘turd’ to every resounding step. As soon as they turn the corner‚ we dim the light and keep our traps shut. They feel a sense of desecration. They penetrate the hostile darkness with a tremendous fear in their guts‚ like a man who’d force himself on a woman who resists.

A power failure. Apparently this is now a frequent occurrence. The proprietress‚ Pignolette‚ the only person Cyril introduced me to‚ lights some candles. I then observe the watchmaker’s face (in normal light he looks forty years old at most).

Countless‚ extraordinarily fine‚ parallel wrinkles leave no area of his skin unmarked. He looks mummified. I recall Georgette’s words. Cyril has already got me to recount my adventures. Now it’s his turn.

Having joined the Foreign Legion under an assumed name at the outbreak of hostilities‚ luckily he put up a good fight. Military Cross and distinguished service medal. Didn’t get caught. They let him keep the name he’d adopted: so he’s issuing his own bill of health. But since Cyril‚ as I well recall‚ once described to me‚ in great detail‚ the fighting he was involved in on the French Front in the 1914–1918 war‚ as well as the famous Kiev massacres‚ when the Shirkers were tied to the rails and slow-moving locomotives sliced off their heads‚ this story bothers me slightly. This matter of time. And of being in so many different places.

People considered ‘reputable’ because of their three-piece suits are gathered here together with genuine tramps‚ shovelling down the same grub. I noticed the bespectacled fellow on the end of the bench‚ his crew-cut hair‚ his very dark-ringed protruding eyes. Cyril whispers‚ ‘Apparently he’s a poet. His name’s Robert Desnos.’

I asked for the key to my room.

Exhaustion has made me hypersensitive. A rheumy lorry passes by‚ a very long way off. I hear it‚ I sense it descending Rue Monge. It’s going to drive round the square‚ turn into the boulevard on the left. I can ‘see’ it. I’m sure of it. It sends a shudder through cubic kilometres of buildings. This evening the neighbourhood’s nerves are on edge.

Ici tous les plafonds ont eu la scarlatine

Ça pèle à plâtre que veux-tu – ô Lamartine …

[Here all the ceilings have had scarlet fever

As you’d expect the plaster’s peeling – O Lamartine …]

That dark‚ circular‚ ringed stain above the bedside table is where the petrol lamp used to hang‚ stinking and leaking like nobody’s business. A nasty fly-specked light bulb dangles over my head‚ swinging fractionally. It makes the shadows move. The lorry draws closer‚ and the disturbed shadows cannot quite settle back into place: then the room itself shares in the general unease.

Mobilization had caught me by surprise on my return from a trip to Eastern Europe. In my bohemian two-roomed apartment‚ I’d accumulated documents and books about the history of Paris. I’d not had time to read them.

I slipped into my place during the day. The Germans have put a seal on my front door: that’s to say‚ two strips of what looks like brown wrapping paper stamped with the eagle and swastika. They think they can impress the world by such pathetic means. For me‚ it was child’s play to get inside‚ gather together a bundle of linen‚ documents and books‚ put everything back in order and leave without being seen.

So I retrieved‚ among others‚ Paris Anecdote by Privat d’Anglemont‚ the 1853 edition; a huge and a very old collection of Arrests Mémorables du Parlement de Paris; and two precious notebooks that will enable me to collate records of events‚ places and dates. Besides‚ the Nationale has once again opened its doors to me. Also‚ the Arsenal‚ St Geneviève‚ and the Archives. I’ve managed to reconstruct a medieval legend‚ which relates to the very place where Cyril has been working for so many years. Here it is.

In 1465 the Ruelle d’Amboise‚ which led from the river to Place Maubert‚ originated in the teeming industriousness of Port-aux-Bûches. The sluggish Bièvre formed a kind of delta at that point‚ before mingling its muddy tannin-polluted waters with those of the Seine. Unsquared logs were left to pile up in the stagnant mud that made them imperishable. A brooding unease overhung Paris. Charles the Bold’s forces were sweeping down from the north. Along the Loire‚ the Bretons‚ won over to the Burgundian cause‚ were pressing hard on the Duke of Maine’s people. Francis of Brittany and the Duke of Berry had also joined forces against the crowned king‚ Louis XI. In the City itself‚ the Burgundians were plotting. The overextended police forces were unreliable. So there was a relaxation of the vigilant watch kept on the serfs‚ semi-slaves‚ vagabonds‚ pedlars and hawkers congregated below the walls of the town.

On the very site of Cyril’s shack‚ a watchmaker who had arrived from the Orient‚ a convert to Christianity who displayed ‘great piety’‚ set up business. He made‚ sold and repaired time-pieces‚ which were extremely valuable and rare in those days.

His clients were inevitably members of the nobility or wealthy merchants. Tristan the Hermit‚ who lived in a house very close by‚ appreciated the watchmaker’s skill and had taken him under his patronage.

The watchmaking trade was thriving. The Oriental had repudiated his barbarous name and called himself Oswald Biber. (Which means ‘beaver’ as does the old French word ‘Bièvre’.) The wily fellow lived frugally‚ and yet he was known to have become very wealthy. Meanwhile‚ some Gypsies who had been driven out of the City established their encampment in the vicinity of Port-aux-Bûches. They read the future in tracings made in the sand with the end of a stick‚ in the palms of women and the eyes of children.

Some prelates got upset and condemned this as magic. But there wasn’t enough wood in the entire port to burn all those who rightly or wrongly would have been accused of witchcraft. The Gypsies – at that time they were called ‘Egyptians’ – were on good neighbourly terms with the watchmaker. Perhaps it was because of this that a rumour developed and gained currency‚ according to which the pious Biber was in reality in possession of forbidden secrets. With the passage of time it had to be acknowledged that such was the case.

Some of his clients – the oldest and wealthiest – seemed less and less affected by the burden of their years. They were rejuvenated‚ and old men beheld with astonishment those whom they believed to be their contemporaries become once again men in their prime.

It was discovered that Biber had in great secrecy made watches for them that were little concerned with telling the time: they ran backwards. The fate of the person whose name was engraved on the watchwork arbors became linked to that of the object. His life went into reverse‚ returning through the term of existence he’d already lived. He grew younger.

A brotherhood established itself among the beneficiaries of this marvellous secret. Many years passed.

And then one day Oswald Biber received a visit from his assembled clients. They entreated him‚ ‘Could you not make the mechanisms that rule our lives just mark time now‚ without regressing any further?’

‘Alas! That’s impossible. But consider yourselves lucky. You’d have been long dead if I hadn’t done this for you.’

‘But we don’t want to get any younger! We dread adolescence‚ oblivious youth‚ the dark night of early childhood‚ and the inescapable doom of returning to limbo. We can’t bear the haunting prospect of that inexorable date‚ the preordained date of our demise.’

‘There’s nothing to be done about it‚ nothing more I can do for you.’

‘But we’ve known you for so many years now‚ and why do you still look the same as ever? You seem to be ageless.’

‘Because the master I had in Venice in times long gone by‚ who did not to my great regret instil all of his knowledge in me‚ made for me this watch here.

‘The hands run alternatively clockwise and anticlockwise. I age and rejuvenesce every other day.’

Unconvinced‚ these aspirants to eternal life of the flesh went away and conferred. It was decided they would return to Biber the sorcerer after nightfall and compel him by whatever means necessary to do as they wanted.

They invaded his house but he wasn’t there. Every one of them had come‚ too‚ with the secret intention of stealing the watchmaker’s watch‚ the only one of its kind offering such comfort.

They fought savagely among themselves‚ and in their struggle the object that controlled all the others was shattered.

Their watches stopped immediately‚ and immediately these fine fellows died. Their corpses were discovered and solemnly execrated. They were piled up in a charnel house in a place where ‘the soil was so putrefying that a body decayed in nine days.’

At the time I almost regretted having mentioned this to Cyril. I’d already noticed his subtle turn of thought‚ appreciated the soundness of some of his advice. The unanimous opinion of folk in the neighbourhood could be summed up in these words: Cyril knows things that others don’t. But I wasn’t aware that he was the holder of a secret – his own – and that to be reminded of it was so painful to him.

All I said was‚ ‘Are you at all familiar with a legend about time running backwards… Oswald Biber …’

He paled‚ began to tremble. In a broken voice‚ staring at me with a kind of terror‚ he said as if to himself‚ ‘So you too are in the know? It’s much more serious than I thought.’

For a moment there was infinite distress in his eyes‚ rising from the most distant past.

And then he recovered‚ and we spoke of other things.

Chapter II

Occupied Paris is on its guard. Inviolate deep down to its core‚ the City has grown tense‚ surly and scornful. It has reinforced its interior borders‚ as the bulkheads of an endangered ship are closed. You no longer see between the villages of Paris that self-confident and good-natured human traffic that existed just a few months ago. I sense a resurgence and reassertion‚ growing stronger every day‚ of the age-old differences that set apart Maubert and La Montagne‚ Mouffetard and Les Gobelins. To say nothing of crossing the bridges: left bank and right bank are not two different worlds any more‚ but two different planets. Often I feel the need to get snugly settled in a corner seat‚ quiet and alone‚ with the complicit smile of some boundary-mark‚ some stone‚ on the other side of the window‚ addressed to me alone. With the pleasure of seeing‚ on this stretch of wall‚ the poster that flutters in the drama of early morning calling for my attention. It knows that I’m responding.

I make this neighbourhood my own. But bowing to social conventions is now a thing of the past. I literally turn my back on one fellow‚ said to be likeable and of irreproachable behaviour‚ who offers me his plump paw. But I’ve no objection to being surrounded‚ like some precious stone embedded in rock‚ by a bunch of sweet-natured winos. There’s Gérard the painter‚ who has a trichological obsession. On the first of every month he gets his hair dressed like that of a musketeer. By the second week he looks like a Russian peasant. There’s Séverin the anarchist‚ who deserted for the sake of a girl. And there’s Théophile Trigou. In order to attend mass at St Séverin every morning without being seen‚ this Breton resorts to the same cunning as the rest of us do in pretending to be unaware of his harmless subterfuge. Théophile is a first-rate Latinist‚ to which we owe some terrific evenings now and again. The four of us form ‘the Smart Gang’. That’s the name Pignolette gave us. She’s fond of us and so she looks after us.

Yesterday we descended on the Vieux-Chêne‚ run by the Captain. A genuine ex-merchant marine officer.

Sunset’s the best time to take a stroll down Mouffetard‚ the ancient Via Mons Cetardus. The buildings along it are only two or three stories high. Many are crowned with conical dovecotes. Nowhere in Paris is the connection‚ the obscure kinship‚ between houses very close to each other more perceptible to the pedestrian than in this street.

Close in age‚ not location. If one of them should show signs of decrepitude‚ if its face should sag‚ or it should lose a tooth‚ as it were‚ a bit of cornicing‚ within hours its sibling a hundred metres away‚ but designed according to the same plans and built by the same men‚ will also feel it’s on its last legs.

The houses vibrate in sympathy like the chords of a viola d’amore. Like cheddite charges giving each other the signal to explode simultaneously.

The Man Who Repented of Betraying a Secret

The Vieux-Chêne was the scene of bloody brawls between arch thugs. By turns a place of refuge‚ conspiracy‚ crime‚ it was frequently closed down by the police.

I was planning on a session of sweet silent thought‚ with a pipe to smoke and memories ready to be summoned.

It was not to be. Silence‚ like madness‚ is only comparative. We felt embarrassed‚ almost intimidated‚ my companions and I‚ by the absence of the usual screen that guaranteed our isolation: that cacophony of belching‚ gurgling‚ stomach- rumbling‚ incoherent ranting‚ singing‚ belly-aching‚ swearing‚ drunken snoring – all this was missing.

The local dossers and tramps were there as usual. But silent‚ anxious‚ watchful – fearfully so‚ it seemed – as they gazed at a spare lean man dressed in black‚ and disgustingly dirty. Leaning forward with his elbows on the table‚ huge-eyed with pouches that sagged down his face‚ he sat staring at a newly lighted candle standing some distance in front of him.

The Captain signalled to us – shh – and went creeping out to bolt the door.

The minutes seeped away like wine from a barrel.

The dossers’ eyes went from the candle to the man‚ from the man to the candle. This carried on for a while‚ a very long while. When the candle had burned two-thirds of the way down‚ the flame lengthened‚ sputtered‚ turned blue and flickered drunkenly‚ like the delinquent dawn of a bad day. Then I knew who the man was. I’d encountered him before.

Just after the last war‚ I spent some of my childhood (the summer months‚ for several years in a row) at E‚ a small town in the Eure-et-Loir. I had some playmates‚ who were entranced by all the things the ‘big boys’ got up to‚ that’s to say‚ boys three or four years their senior. These ‘big boys’ affected to despise us. They never joined in our games‚ but they were happy to capture the admiring attention of an easily impressed gaggle of kids. The most conceited‚ big-mouthed show-off‚ and sometimes the meanest of these older boys‚ was called Honoré.

We hated him as much as we loved his father: Master Thibaudat‚ as he was known. This good-hearted fellow – I can still see his blue peaked cap‚ his Viking moustache‚ and the reflection on his face of his smithy’s furnace – repaired agricultural machinery. He was also captain of the town’s fire brigade. This was no small distinction. Every Sunday morning he’d gather together his helmeted and plumed subordinates for fire drill. He’d get them lined up in rows outside the town hall‚ and direct operations in his manly voice with a thick Beauce accent.

‘Pompe à cul! Déboïautéi!

‘Mettez-vous en rangs su l’trottouèr comm’ dimanche dargniéi!

‘Hé là-bas: gare les fumelles … on va fout’un coup d’pompe …’

[Drop the hose reel! Let it run!

Line up on the pavement like last Sunday!

Hey‚ watch out there‚ lasses … we’re going to give it burst …]

What a laugh!

The rest‚ I found out later.

For there was something else: Master Thibaudat was ‘marcou’. In other words‚ he’d inherited from his ancestors the secret‚ passed down from father to son‚ of mastering fire.

Thibaudat had the ability to extinguish a blazing hayrick‚ to isolate a burning barn‚ the strategic genius to contain a forest fire. But more importantly‚ he was a healer. Mild burns disappeared at once; the rest never withstood him more than a few hours. In very serious cases‚ he would be sent to the hospital. There he would pass his hands over the agonized patient who would be screaming and in danger of suffocating. At the same time he would recite in an undertone set phrases known only to himself. The pain would cease immediately. And flesh and skin would regenerate with a speed that astounded numerous doctors. From Maintenon to Chartres‚ and even as far afield as Mans‚ Thibaudat is still remembered by many people.

The day came when Master Thibaudat sensed that his powers were failing. He feared that he no longer had the vital energy he needed to be able to do his job. His only son‚ Honoré‚ was a now grown man: for his eighteenth birthday he’d been given a new bicycle and a pair of long trousers. His third pair.

Under solemn oath to hold his tongue‚ Honoré was initiated into the family secret and in turn became ‘marcou’.

Honoré got more and more above himself. He’d stuck with the same bunch of friends because‚ being better dressed than they were‚ and with plenty of money in his pocket‚ he more easily cut a dash at the country dances‚ especially at a time when the day-labourers‚ not satisfied with the sluts they were fobbed off with in the bordellos – ‘Good enough for peasants! Incapable of screwing without the rest of the gang in tow‚ and drunk as skunks!’ – were happily treating themselves to young housemaids‚ getting them pregnant or giving them a dose of the clap‚ without a by-your-leave or thank-you and no time to call mother.

Honoré at least had some style and manners. And the means to compensate his partners for the loss of half-a-day’s pay. And to find modest sheets to lie between‚ under a feather counterpane that with two kicks and a pelvic thrust was soon sent flying in the direction of the ceramic-edged chamber-pot with the blue enamel lid.

‘Now‚ what was it your father told you‚ Honoré? What do you have to say to draw the heat? Is it a prayer or a spell? Go on‚ tell me‚ Honoré …’

Forgetting his oath‚ Honoré spilled the beans on several occasions. He’d already exercised the power passed on to him‚ on some not very serious injuries. The patients had been cured: less rapidly‚ however‚ than if they’d been treated by the father. But allowances had to be made. Honoré would eventually get the hang of it.

The hat shop in Rambouillet had prospered. In the workshop‚ twenty women in front of twenty sewing machines turned out twenty snoods of woven straw‚ dreadful things for imprisoning chignons. Two girls from the area round E found themselves working side by side. One of them boasted of her experience – and enjoyment – of the seductive charms of the handsome Honoré. Her neighbour‚ stung to jealousy‚ claimed to be equally knowledgeable on this subject. There was no way they could start tearing each other’s hair out. But the girls were obdurate. At a loss for insults‚ vying to have the last word‚ they hurled at each other those phrases that were not to be uttered‚ the phrases unwisely divulged by Honoré. And once let loose‚ those words were soon all over town.

The child that had fallen on to the fire in the hearth was brought before Honoré‚ who with the laying-on of his hands began to murmur. A quarter of an hour later the child was dead.

Then the rumours gained substance. And people grabbed their pitchforks‚ their flails and some their guns. The ‘marcou’ had become ‘malahou’‚ in other words‚ forsworn‚ a traitor to his word‚ a traitor to everyone.

It required the energetic protection of the police to allow Honoré to get on his bike and reach the very distant station of Gazeran‚ where the Paris train stopped.

Old Thibaudat died shortly afterwards – broken-hearted‚ so they say. Banished from that region for ever‚ Honoré got on the wrong side of the law. He spent his military service doing time with one of the Africa Disciplinary Battalions.

The extinguished wick was still smoking‚ through distraction – amazement‚ perhaps.

The dossers began to talk among themselves‚ suspecting one another of being the one that had blown out the candle without anyone noticing. The man in black seemed at once crushed and relieved. I don’t know why I was so cruel.

‘Honoré Thibaudat?’

His lined face became even more gaunt. The same terrified bewilderment‚ the same overwhelming distress I’d witnessed in Cyril. But this lasted much longer. With great difficulty he formed the words‚ ‘What … what do want?’

‘Nothing. Are you the son of the fireman at E? We used to know each other.’

‘So … so what? What do you want of me?’

‘Nothing‚ I tell you‚ nothing at all. Let me buy you a drink.’

‘He only drinks lemonade‚’ said our host.

Honoré seemed unable to breathe. ‘Yes … yes … with lots of ice‚’ he said.

In three large glassfuls‚ three single draughts‚ he’d emptied his bottle of lemonade. He looked at me. This time with the eyes of a beaten dog.

‘So … you know the story?’

We still had twenty minutes before the curfew. Honoré and I walked back up La Mouffe side by side. He pointed to a basement window. ‘I sleep there‚ in the cellar. It’s cooler. Since back then‚ especially since Africa‚ I have this burning sensation. Here.’ He ran a trembling hand over his larynx. ‘Nothing I can do to relieve it. Tried everything‚ including injections. Afterwards‚ it comes back‚ worse than ever. Sometimes I can even extinguish live embers. But that takes it out of me. I’m already an old man.’

It was true. At forty years of age‚ he looked seventy.

He yelled‚ he bellowed‚ ‘What must I do? What must I do?’

And I left him there in the dark‚ sobbing in repentance for the secret he’d betrayed.

December

It’s really very‚ very cold. People are hungry. Rations are inadequate. Nothing to line your stomach. The tramps‚ who for years have been part of the landscape‚ are dying like flies. Only the strongest survive. For those that deign to stir themselves there’s no lack of work – luckily. They have only to be on the street by five in the morning (any earlier is prohibited) and start going through the dustbins. Never has the price of paper‚ fabric and scrap metal been so high. And it’s still soaring. The master rag-pickers – wholesale rag-traders – are beginning to build up real fortunes. The tramps couldn’t care less. They’ll earn just enough to stuff their faces with no matter what‚ no matter how‚ no matter where – and to fill their stomachs with enough plonk to keep them in a drunken stupor till the next time they waken. That’s all they ask.

The Shipwreckage Doll

Yesterday Old Hubert was found dead‚ frozen stiff‚ behind the bar. The rats had started in on the exposed softer parts: the neck‚ the cheeks and the fat of his palms. We’d seen it coming for a long time. No one was surprised. You can still make out on the front of his shop: Coffee – Wines – Liqueurs – Hotel with Every Comfort. Every comfort? What a joke!

Rue de Bièvre‚ number 1A‚ right by the river. Two and a half storeys – in other words‚ you’d have to be a dwarf or amputated at the knees to able to stand upright under the sloping roof. From the outside it looks at least as respectable as the other hovels in the street. But just go up to the first floor‚ and you know the score. The walls are caving in or bulging with damp. The landings are pitted with holes – pot-holes. The resident population is made up of (or breaks down into) five households‚ three unsanctioned by marriage‚ with a total of twenty-one children between the ages of two and ten‚ not to mention the babes-in-arms. All the fathers share a physical resemblance: they’re midgets. Not one of them even as tall as one metre sixty. Nowhere near it. And there’s another defining characteristic they have in common: they’ve done absolutely nothing for many‚ many years. Just a matter of bad luck! All of them skilled workers of one kind or another‚ but so highly skilled‚ and as ill luck would have it so inappropriately skilled‚ that any job that might be available never matches their skill. It’s a near thing every time. Which means unemployment‚ welfare‚ child allowance‚ assistance for this‚ benefits for that‚ social‚ unsocial‚ antisocial …

A man can get by pretty well on this‚ and keep his whistle wet. But paying the rent‚ that’s another story. Wait till the landlord starts moaning before you give him something to keep him off your back. It wasn’t in old Hubert’s nature to give anyone a hard time. He’d already been served notice to carry out urgent health and safety repairs to his building. And with what millions? Forget it! With the Huns here‚ and everyone hard up‚ this was no time to be hoping for so much as a brass farthing. So what? Evict them? Unthinkable! Old Hubert simply decided to ignore the existence of the hotel. He condemned his own bedroom on the first floor as unfit for habitation‚ and started living in the bar.