Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Can Gala resist the ties that bind, or will she be drawn once more into a world skewed by fear and suspicion? To avoid being caught in the web of her father's self-delusion, she fled to another continent. Now she has returned, she must confront the unbearable weight of her past. A flawed father is seen clearly at last through his daughter's eyes in a multi-layered narrative that echoes the shifts and loops of memory. Delicately drawn in fragments of memory, Pelmanism is a moving journey of self-discovery. With her father's breakdown, Gala finds herself pulled back into the toxic family dynamics she thought she had eluded. Through ripples of the past, we begin to piece together the reality of a family that has lived a lie for as long as she can remember. But what kind of truth can memory really offer?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 314

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

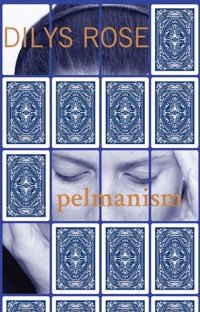

DILYS ROSE lives in Edinburgh. She has published eleven books of fiction and poetry, including Red Tides, Pest Maiden, Lord of Illusions and Bodywork and her work has received a number of awards. As well as going solo, she enjoys creative collaborations with visual artists and composers; she is currently working on a song cycle and researching a new libretto. She is programme director of the online MSc in Creative Writing at the University of Edinburgh.

Pelmanism

DILYS ROSE

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

First published2014

ISBN: 978-1-910021-23-1

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-910324-00-4

The publisher acknowledges the support of Creative Scotland towards the publication of this book.

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988has been asserted.

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Homage to R.D. Laing

Oilseed Rape and Porridge Oats

Diving Through Fire

Walking on Water

Al Forno

In With the Freaks

Barras

Bohemians

Waterwings

A Lack of Faith

Marigold Yellow

Wood

Dog Obedience

Living with Marlene

Amateur Dramatics

4X, Hut B and the End of a Possible Career

Clay

About a House

Tarnish

Splitting Hairs

Surf &Turf

Swipe!

Diversion

Fairways, Roughs and Bunkers

Wedding Belles

Relegation of the Wheel

Galaxy

Figuratively Speaking

Perspective

Nothing Like Family

Swansdown and Diamante

Deconstruction of a Turban

The Art of Sitting

Paint it Black

Likely Lass

Gino’s

Pelmanism

Deadlines

Sea Jade

Gooseberries

One Man Show

Aftermath

Our Lady of the Iguanas

Still Life with Dimple

Passed Over

Season of the Heart

Rumpus

The Pips

A Whispering Gallery

for my friends

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks are due for various help and support, to the following people: Geraldine Cooke, Louise Hutcheson, Sara Maitland, Jenni Calder, Jennie Renton, Barbara Imrie, Joan, James and Dorothy Parr, and Sally Whitton.

I would also like to thank the administrators and caretakers of Ledig House and Le Château de Lavigny, for greatly appreciated writing space and time, and for great food, views and company.

Homage to R.D. Laing

whatever they do

they must not no matter what

let him know they think

something’s not right

whatever they know

they must not no matter what

let him think they know

something’s not right

whatever they think

they must not no matter what

let him know they know

something he doesn’t

Dilys Rose

Oilseed Rape and Porridge Oats

GALA’S MOTHER ISwaiting on the station platform, though the plan was to meet at the car park and avoid a grand public reunion. As Vera Price is the only person meeting the train it doesn’t matter much, and she has waited a while for this moment. She waves frantically and Gala can’t help slowing down, postponing the moment of contact. Her mother looks smaller than she remembers her. Thinner. Her hair has turned a gun-metal grey and she’s had it cut, in an androgynous, institutional chop. In pressed ecru trousers and a short-sleeved aqua shirt, she could be anybody’s mother but she is Gala’s, waving and smiling widely and hurrying towards her daughter, who puts down her weekend bag to receive an awkward hug.

Let me look at you!

Vera takes a step back but keeps a firm hold on Gala’s shoulders, as if her daughter might turn tail, bolt along the platform and leap onto the train which is huffing and puffing and preparing to pull away from the platform. The thought does cross Gala’s mind. The longer she stays away, the harder it is to come home. No, not home; back. This place was never her home. In her absence, while she was gallivanting on another continent with no clear plans for the future, her parents moved house again, this time relocating to the other side of the country, to the quaint coastal town, where they met. On the beach. Then, horses were involved. The other, less romantic reasons for the move, are rarely mentioned.

You’ve cut your hair!

Yes, says her mother. I don’t like it but it’s easier. Anyway, nobody cares what you look like at my age. You’ve lost weight! She tries to wrestle Gala’s bag into her possession. How long are you staying?

Just a couple of days.

Couldn’t you make it a bit longer?

Not this time. I’ve a lot to sort out –

It’s been so long since we’ve seen you. And Dad –

Again she tries to take control of the luggage, to make it her responsibility, her burden.

I can manage, Mum. I’ve been carrying my own bag for long enough.

Only trying to help. Are you working?

Not yet. I’ll get something soon.

There’s a lot of unemployment now. Mrs Thatcher says –

I really don’t care what Mrs Thatcher says.

Her mother’s lip wobbles, eyes pool. Why didn’t she bite her tongue? Why wind up her mother about fucking Thatcher?

Sorry. But politics – is there any point in talking about politics?

No. Politics don’t matter. Nobody ever keeps their promises, politicians or otherwise.

Gala stifles a sigh. When they are midway across the railway bridge, two fighter jets burst into the sky and roar overhead, close enough to feel the knock of displaced air. Ever sensitive to noise, her mother clamps her hands over her ears.

Such a racket, says Vera. We thought about getting a house over this way but the noise from the air base put us off. And Dad said being reminded of theRAFevery minute of the day would be adding insult to injury. During the war he wanted to be a pilot but the air force didn’t take him.

I know, Mum.

It’s always irked him.

I know.

The jets disappear over the brow of the hill, leaving dirty black trails against an otherwise clear sky.

As Vera descends the clanking bridge, she takes Gala’s arm. There’s a waver of uncertainty in her step.

A grand day, she pipes up, bright but brittle. The countryside is at its best.

It’s lovely.

The shimmering air has a salty tang. Poppies nod by the roadside. Fields of blue-green cabbage and ripe wheat sweep down to the coast where a frill of breaking waves edges a vivid, turquoise sea. All pretty as a picture but for a large, acid yellow field, so intense in colour that it looks artificial.

Rape, says Vera. Horrible. Gives me headaches. A cash crop. It’s subsidised by the government. An eyesore. And people say it causes allergies.

She rummages in her bag, plucks out sunglasses with sugar-pink frames, sticks them on her straight, classical nose and stops in front of a shiny blue car. Prussian blue, Gala’s father would call it.

Did we have this car the last time you were home?

I’m not sure.

Gala has never paid much attention to her parents’ cars. Every couple of years they trade in their two-year-old model for a new one. Something to do with depreciation. Her parents are organised about such things: value for money, maintenance, repairs. Whatever else might be falling apart, their material world is in good enough nick.

The car smells of synthetic upholstery, pine air freshener and stale tobacco. The seats are hot, itchy. Gala rolls down the window, lets in the sea air.

Okay if I smoke?

You didn’t quit? You said in your last letter that you were thinking of quitting.

No, Mum, I didn’t quit.

Go on, then. Your father is back on the pipe. They only let him smoke out of doors. The grounds are really very nice, and very well kept, not a weed in sight, I don’t know how they manage to keep the dandelions at bay, but he kicks up a fuss about all the rules and regulations. Especially the smoking policy. You’ll see a change in him.

How has he been?

Up and down.

When do you think...? Gala lights up, inhales.

What? When do I think what?

Nothing. Nothing. Those poppies are pretty.

Say what you were going to say.

I was just wondering how long he’s likely to be – how long they’re likely to keep him.

Depends. On a number of things.

Her mother grips the steering wheel and crawls along, anxiously eyeing the needle of the speedometer.

Got to watch my speed around here. Speedtraps everywhere!

Mum, nobody in their right mind is ever going to doyoufor speeding!

What d’you mean theirright mind?

Nothing. Sorry.

Her mother is the slowest driver in the world, which is not to say she’s the most careful.

They caught your father. He got a ticket.

I thought you said he lost his licence.

He did. The speeding ticket was just the beginning. Did I tell you he turned the car over?

Maybe. I’m not sure I got all your letters. I was moving around a lot and theposte restantewasn’t always reliable.

It was a write-off. He’s lucky to be alive.

And no injuries?

Nothing to speak of.

Hewaslucky then, said Gala. Very lucky.

If you ask me the police did him a favour taking away his licence. At least until he sees reason. Whenever that’s likely to be.

A whiff of something rank comes in the open window.

The paper mill’s stinking today, says her mother, but it does produce lovely paper. Did you bring your sketchbooks? I’m sure Dad would love to see some sketches from your trip.

I don’t have any. Lost the lot en route.

What a shame!

It was my own fault. Can’t be helped.

In fact Gala’s bag was stolen from the luggage compartment of a Mexican bus but there’s no point in getting into that.

What about photos? Do you have any photos?

I didn’t take a camera. I try to remember what’s important.

Do you really? But how do you know what’s important?

If I remember something, it’s important.

Oh well, says her mother. Good to know your own mind, I suppose. I could get you some nice paper from the mill and you could draw what you remember.

I’m not drawing at the moment.

But for Dad – couldn’t you draw some pictures for him?

I can’t see what good that would do.

Anything’s worth a try! says her mother, her voice thin, scratchy.

They are entering a drab little market town with close-packed streets, a dreary mix of rundown, post-war façades and cheap and cheerless makeovers. Gala hasn’t passed this way since she was a child but little has changed: the window displays are dated and uninspired. The trading names are heavy on puns, alliteration and stating the obvious: Patty’s Pie Pantry, Hairwaves, Message in a Bottle. The pavements are choked with young mums dragging truculent toddlers, heavy-set matrons rocking along with bulging supermarket bags as ballast, wizened grannies steering wobbly wheelie baskets around cracked slabs. Boozers jaw at The Cross. Crusty old boys walk hirpling dogs. Young blood props up the war memorial.

I thought we’d just go straight to see Dad.

Right now? I thought maybe – Gala smokes again, to stall her tongue.

What? What did you think?

I thought we could do that tomorrow.

But your father’s expecting you. He’s been expecting you for –

I’m just, well, I’ve been on the go for ages and I’m tired.

Tired? You’retired? Do you think I’m not tired? You haven’t seen your father in all this time and you’re wanting to put it off another day? I told him you were comingtoday.He does know the difference between one day and another, you know. He does have some perception of time, even if it’s not quite the same as – He’s expecting you. Looking forward to seeing you and he has precious little to look forward to. What am I to tell him now?

Okay, it’s fine. Calm down, Mum, it’s fine. We can go now, if you want.

Her mother grinds down a gear and the car jolts, causing the driver behind to brake sharply and lean on his horn.

I wouldn’t want topressuriseyou into going to see your father, whom you haven’t seen for what – two years? – even though he’s stuck in that godforsaken place and gets hardly any visitors. I certainly wouldn’t want to dothat.

I said it’s fine. Let’s go and see him. It’s fine.

Gala puts a hand on her mother’s shoulder, feels the silent judder of weeping. She hates it when her mother cries. And hates herself when she is the cause. But why does her mother have to cry so easily and so often?

Anyway, Gala says in her least confrontational voice, we’ve come this far already. No point in wasting petrol.

The town has tailed off to a straggle of low, terraced houses fringed by trees and fields. A smell of turnips wafts through the window, then manure, then something sweeter, toasted.

The porridge factory. We’re nearly there.

Once again grinding the gears, her mother turns off the road and onto a long, tree-lined drive.

Your father will be so pleased to see you. By the way, even if he’s up and about, he might still be wearing pyjamas. No need for alarm. And even if he doesn’tseempleased to see you or interested in what you say, he is really. He just doesn’t always show it. Usually it’s only me who comes to visit. And your brother, he’s very good about visiting. When he can. He was hoping to be here today, to see you, but something came up.I don’t know what. He doesn’t tell me much and when he does offer any information, I sometimes wish I hadn’t asked. But he and I don’t have much to say that your father hasn’t heard before, whereas you must have so much to tell him. Of course you don’t want to upset him. You must try not to upset your father.

After a bend in the drive, a large plain whitewashed building comes into view. Above the doorway, a large sign says: Welcome to The Pleasance. All Visitors Report to Reception.

Diving Through Fire

HER FATHER COULDdive through fire. That’s what they said and Gala could picture him up on the dale, puffing out his fuzzy chest, sucking in his stomach, flexing skinny white legs as he worked up to the big finale. The dale was at the far end of the pool, a distance from the spectators’ gallery and the changing rooms. Sixty-five clanging steel steps led to the concrete diving board. She knew how many steps because she’d counted as she climbed, then walked the length of the platform, peered over the edge, balked at the drop and, scaredy cat that she was, ignominiously retraced her steps.

For the spectators, no matter how sheltered a spot they thought they’d found on the peeling wooden benches, a sharp sea breeze slithered around the rocks and wormed through pullovers and windcheaters. They watched and waited. The pool attendant climbed part way up the diving tower and set a long, lit taper to the ring suspended between the top board and the water. Over from the west with his family, Miles Price, father of two, school teacher, weekend artist and, in the summer holidays, relief lifeguard, flexed his legs and extended his arms. The ring of fire flickered orange against a lavender dusk.

Already he had retrieved bricks and car keys from the bottom of the diving hole and with the aid of a rubber dummy, had demonstrated life-saving techniques. He had catapulted himself off the springboards into pikes and back flips and somersaults, but diving off the dale through a ring of fire would be his crowning moment.

The ring was a band of steel with kerosene-soaked rope wound round the frame and supported by two poles strapped to the central column. The flames danced in the light breeze. The ring quivered. As it had to be a tight enough fit to display skill and accuracy, to introduce an element of danger, the possibility of harm, it was not much bigger in circumference than a hula hoop. If there hadn’t been a chance that the diver might have misjudged his angle of entry and scorched his skin, who’d have bothered to watch?

When he had fine-tuned his limbs and filled his lungs he took off, arcing upwards, jackknifing mid-air then stretching out and shooting clean through the flames. He entered the water with little more than a ripping sound like torn paper and a crown of bubbles gathering around the disappearing tips of his toes. Deep in the indigo pool, his plunging body hollowed out the curve of a boomerang. Applause rippled through the gallery. When he surfaced, climbed out and posed, Olympian, by the diving tower, the ring of fire flickered like the halo of a dark planet.

The thing is, Gala is not sure she really saw the show. She knows it happened because it was mentioned often, particularly by her father, and she can picture him, after the event, in drippy, droopy trunks, towel slung round his neck, eyebrows slightly singed. She can smell kerosene, scorched rope. As the crowd files out through the turnstile, he saunters towards the changing rooms, flushed with glory. As clear as can be, she can recall the dale, the sea beyond the pool wall rocking and slapping, and the distant lights of a fishing smack winking like a low-slung constellation. She can see the ring flickering against the deepening dusk but her father; did she really witness him diving through fire?

Walking on Water

SOMEHOW, THAT AFTERNOON, nobody was around. Stepping onto the pool wall in a still-dry swimsuit, Gala felt brave, bold. At the deep end the tide was already slopping over the wall. It was a big pool and, deserted, seemed bigger than ever. Beyond was a jag of rocks where a geyser of spume obscured the crumbling castle ruins. The castle was famous for its bottle dungeon. In the old days prisoners were dropped through the long, narrow bottleneck and fell to the bottom. It was said to be impossible to escape. Unless you could dig a tunnel through solid rock with an old bone.

Overhead, a gull swung through the damp grey air, crying and crying. As she made her way along the wall, arms outstretched like the tightrope walker she fancied she might be when she grew up. The heat of the veiled sun warmed the back of her neck. Walking on walls – the higher the better – was a favourite pastime. Whenever she got the chance she’d be up there, teetering, but a wall surrounded by air is nothing like one with sea slapping around. A little kick on the surface, an immense surge below.

The sky was still and heavy, the sea restless and heavy. Tensing her toes she stepped carefully, alert to slime and slither, crabs and jellyfish, anything which might cause her to squirm, to lose concentration, balance. She had to keep herself straight and steady, like a needle on a compass. A small fluctuation either way and she might be able to right herself but if she swung too wide of the mark she’d tip right over.

When the water was low enough to lap her ankles it was easy enough to stay upright, to become casual and confident, to allow her attention to wander. She compared the number of jellyfish wobbling out on the sea side to those in the pool. She charted the progress of clumps of seaweed and a bobbing turd. Which would be worse to come in direct contact with – jellyfish, turd or seaweed?

The tide was coming in quickly. With each step towards the deep end, the sea crept higher up her legs and soon she was setting her feet down on a wall she couldn’t see. Safer to slow down but time with tidal pools is crucial: if she didn’t push on, the tide would beat her back.

At the deep end, a chill came off the water and the rock and suck of the sea was far more menacing than she’d bargained for. Chittering, she looked back with longing to the shallow end, the paddling pool and the soft, safe, grassy bank. Where was everybody? Where was her father? Was her mother having an afternoon nap with her baby brother, in the boarding house which smelled of boiled eggs? Where was the man who looked after everything, fishing out muck and weed, netting the flotsam which sloshed in on the tide? And the lifeguard – wasn’t there supposed to be a lifeguard on duty even if there was only one person who might need to be saved?

Gala’s father had a certificate to prove he could swim with one arm while the other was wrapped around the person he was saving but he preferred diving demonstrations. Being a lifeguard, he said, was just a lot of standing around. But nobody was standing around, or even passing by on the esplanade. Was something happening on the other side of the hill which everybody, even Gran, had stopped to watch? Where was Gran?

It was too late now to remember that Gran had told her to keep clear of the water until she arrived. She was far from the warm shallows and grassy bank and had to keep going, to confront the stretch of wall where the tide was strongest and the water highest. Or go back the way she’d come and admit defeat. If she’d been able to swim more than a few frantic doggie paddles or sensible enough to put on the waterwings, which she’d left in the changing rooms, she could maybe have splashed back to the shallow end. Too late to be thinking about that now.

She took a deep breath, the way she’d seen her father do before he dived in and tunnelled underwater like a seal. She held the air in her puffed-out chest and high-stepped it, fast and anxious. The water was up to her knees. It knocked her about. Several times she almost missed her footing and the things she felt underfoot, hard, sharp things and slimy, squelchy things didn’t matter a bit in the face of the great swaying, slapping mass of sea which could swallow her up and no-one would know, until somebody walking their dog or flying a kite came across her bloated body, washed up further down the coast; maggots and flies in the empty sockets of her eyes, hair tangled up in seaweed, crabs scuttling in and out of her decomposing mouth.

Stupid, stupid. Every time he took her swimming, her father drummed it into her that she must never go out of her depth. She’d get in trouble for this, for not paying attention, not doing what she was told, she’d get in so much trouble, get such a row, she’d be punished but whatever the punishment it couldn’t be any more frightening than the sea all around, ready to swallow her whole. On the home stretch of submerged wall, she remembered to breathe again, drew in great gasps of air, concentrated on breathing deeply and not making a silly mistake. She’d already made one of those.

So as not to think about falling off the wall, she thought about lungs, how they inflated then deflated, how they couldn’t stay filled, how the air would burst out if you tried to hold it in too long; the air had to be constantly changed, went in good, came out bad, you couldn’t stop breathing in out in out, on and on or you’d turn red or purple or blue and die. Jas had been a blue baby. Almost strangled on his umbilicus.

Somehow all the thinking got her back safely to the shallow end and just as she reached the wide expanse of concrete, the sun broke through the clouds. She whooped and spun around. She’d done it! Safely back on solid ground, the sun was out, the sky blue, she whooped again and spun, high on bravery and boldness and relief – and then she was falling through sudden murky darkness, twisting, tumbling, drifting in no direction, time and space flowing slow and cold, the ringing in her ears as punishing as a dentist’s drill – and then she was spitting and choking and retching, a hand was slapping her back and a voice, a dear, familiar voice was shouting:

Spit it oot, dearie, spit it oot!

Her eyes burned, throat burned, her chest, lungs, belly burned –

Spit it oot! spit it oot!

And Gala spat and gagged and retched up brine and bile. And when she was done, when her throat was raw and there was nothing more to bring up, Gran swaddled her in a towel, and hoisted her, gulping, onto her warm lap. Rocked her like a baby.

Gran’s skirt and blouse were streaked with dark splashes. Her sandals were soaked through. Cream leather turned sludge brown.

Ye’ll be the death o me, so ye will.

I got all the way round!

Whit in heaven’s name were ye thinkin?

It was like being on a tightrope. In the circus.

I’ll circus ye. Ye could’ve been a goner. Did I no tell ye tae save yir tricks till I got here? Dearie me, ye could’ve drooned! Just as well yir faither wisny here tae see me fishin ye oot. He’da strung me up! Made me walk the plank!

Gran filled a plastic mug with hot orange squash from the Thermos flask she brought to the beach come rain or shine.

Get this doon ye. And dinny gulp. Ye’ve done enough gulpin for yin day.

From her pocket, she magicked a dark disk wrapped in waxed paper. A treacle toffee.

Here. Awa and get yir claes on. Dry yourself properly. Mind and no choke on that chaw.

Gran sat herself down on the grassy slope next to the changing rooms and turned the toes of her wet sandals up to the sun.

The changing rooms were dank and smelly, rife with creepycrawlies and spiderwebs with throbbing, tormented knots at their centres. The stuff which usually bothered Gala, the sudden whirr of insect wings, the skewed scuttle underfoot, were nothing that day. When she had dried and dressed and shut the saloon-style door on the rotted wooden cubicle, she ran her dripping costume through the mangle and watched the seawater pour out of it.

By the time she was ready to leave, Gran’s shoes had begun to lighten a shade or two and a salt crust was forming around the uppers. The tide was full in and it was impossible to determine where the pool ended and the sea began.

Back at the boarding house, where the Price family had taken two rooms for the fortnight, Gala pushed down leathery liver and charred onions without complaint. Gran gave her small, meaningful smiles across the table and said nothing at all about her reckless escapade at the swimming pool. That night, snug between crisp sheets and anchored by heavy, scratchy blankets, Gala dreamed she was a bell at the bottom of the sea.

Al Forno

HER FATHER PUTher head in the furnace. Well, not personally. He paid a man to do his dirty work for him. It had been raining in the night and the streets were still wet. He loaded the car with busts and heads and figurines – damp, pale, dead-looking things wrapped in veils of soggy muslin. Gala wore her favourite outfit: cherry red, jersey-knit trousers and a black and white dogtooth top. As it was still wet underfoot she also wore wellies, which rather spoiled the effect. Her mother had brushed her hair briskly and dragged it back with a clasp but hadn’t had time to yank it into pigtails.

The car sat low on the road, a black bug which smelled of leather and petrol and the cigarettes her father enjoyed so much more when her mother wasn’t around to complain about them. Being small, Gala’s outlook was restricted to scarred, soot-black walls topped with barbed wire and broken glass, warehouses big enough to swallow whole towns, a speckled flurry of starlings and the tips of idle cranes.

The ships were the size of cathedrals. You might glimpse the bones of a massive skeleton crawling with hundreds of men or the slow passage of a dark hull slipping between the warehouses on the invisible river. On weekdays the hammering and the sizzling of welding torches never stopped and if you were passing at the end of the day, the lousing siren blared like a declaration of war and men flooded through the gates and onto the street, spreading out, breaking into fast-moving tributaries; heading home or to the pub.

But it was Sunday, the shipyard was silent and the gates bolted. When the landscape became even more abstract and impersonal and tramlines cats-cradled the road, Chitti’s, which rarely shut on Sundays, was nearby. Was there a sign? Gala can only remember an opening, a gap in the wall, the tyres of the Austin squelching over mud.

In the courtyard, waves of heat flapped at her face. Had her father not been fully occupied with his clay models, she’d have taken his hand. Instead, shielding her eyes from the heat, she hung back. He cradled his box as if it were a baby or a cake, and would have been more upset about dropping it, and his work, than about his daughter taking a tumble, skinning her knees and spoiling her Sunday best.

Jas was too young to come to Chitti’s, which made Gala feel important. Chitti’s was exciting. Dangerous. Across the mud, through the archway, deep in the belly of the building, sparks flew and men in filthy singlets slid pieces of metal in and out of the furnace on long flat shovels. The furnace was much hotter than a baker’s oven, hot enough for metal to melt and flow like a white-hot river.

The furnace was where Gala’s head would go eventually but first it would be fired in a kiln. A mould would be made from the fired head and then something else would happen – her father had outlined the process but there were too many stages to remember – and some time later the head, which had started off as pale damp clay, would reappear as dark, lustrous bronze. Unbreakable. Everlasting.Which was also why she hung back. The heat haze bent the air. The foundrymen with big strong shoulders, smutty faces and sweat-shiny chests were scary, in a good way: sharp and thrilling. Her father had a spring in his step, which was also good, but that particular Sunday it wasn’t good enough.

What’s eating you? he asked.

Nothing.

Buck up, then.

It was unthinkable to say she didn’t like the head, or the hairstyle. For the sitting, at her mother’s insistence, and under her mother’s muscular, piano-playing fingers, every strand of hair had been scraped back from her face, tightly braided and secured with nippy little elastic bands. As if loose, free hair was a sign of bad character.

Ah, Chitti! Good man. Hard at it, as ever?

As ever, Mr Price, aye. Time is money.

Chitti was special. At home, his name was spoken in a tone of respect. Chitti was needed, trusted.

Ciao, bella! But why no smile,bambina?

Where’s your manners? said her father.

Manners, spanners, no matter manners. But so saaaaaad is baaaaad!

Manners was something Gala’s parents cared a lot about. There was only one good set, like the electroplated nickel silver cutlery brought out for visitors; bright, shiny manners which involvedPleaseandThank youandSpeak when you’re spoken toandLook at me when I’m talking to youandDon’t mumbleandGrownups know best.

Chitti didn’t care about manners but liked to see smiles. And if she was poker-faced, as she was that day, he’d lark about, do his best to draw a smile from her. Small, top heavy, with arms as long and strong as a gorilla, he hoisted her above his head, twirled her around three times then set her down and in his big, passionate voice belted outO sole mil, sta n’fronte a te!against the infernal racket of the foundry. She couldn’t prevent a small smile from curling the corners of her mouth.

Dere, dere, da’s better,Bella!

Bellameant beautiful. It was also the name of a large, lumbering girl who lived down the road from Gala and wasn’t beautiful at all.Ciao Bellameant Hello Beautiful or Goodbye Beautiful. Chee aaaaaaaa ohhhhhhhh behhhhhlllaaaaa. Those slow, viscous vowels flowing out of Chitti’s throat were sweet as honey.

Her clay head would prove to anybody who saw it – and people would be able to go on seeing it all through her childhood, womanhood, her old age, even after she was dead the proof would be there for anybody to see – thatBellawas not an accurate description: she had fat, ugly pigtails; the sulk made her eyebrows buckle like hairy caterpillars and her lips press together like rubber suckers. Even so, the wordBellaglistened inside her own, flesh and blood head.

In preparation to leave, her father and Chitti went through their customary rigmarole:

A lot on at the moment, Chitti?

Oh yes, very busy, Mr Price.

No rest for the wicked.

Or da good, hardworking man, sir. I dunno where da time goes.

Are you suggesting a long wait is likely?

No no, sir. I say I do for you, so I do.

Glad to hear it.

Except for da unseen circumstance, sir.

Let’s hope we have none of that! Well, I’d better let you get on. Strike while the iron’s hot, heh, heh!

Right you are, Mr Price.Ciao,sir.Ciao Bella!

The pigtails and sulk were handed over for Chitti to work his hot, dirty magic and preserve them forever. As Gala’s head changed hands, she made a wish: a selfish, destructive wish involving the explosive combination of stray air bubbles, hard-packed clay and high temperatures. She flushed at the badness of it but with all the shimmering, distorting heat around, nobody noticed the guilty pinkness of her cheeks.

In With the Freaks

SHE’D SLEPT IN, was running late and her parents didn’t like to be kept waiting. When they’d phoned to arrange the visit, they’d suggested picking her up at the flat:

We won’t stay long, her mother said. We won’t pry.

Gala stalled them, arranged to meet at the National Portrait Gallery. No way were they coming to her current residence, where by accident more than design – it was cheap, she was desperate – she was in with the freaks.

As always the kitchen was a cool, freaky tip. CarolAnn’s fetish gear was mixed up with baby stuff, dope doings and Genius Jake’s ever-growing collection of fertility goddesses. CarolAnn, wearing nothing but a skimpy black slip, was slouched in the high-backed rattan chair, breastfeeding Rainbow Suzi.

Hey, she said, looked up momentarily, then slid her heavy-lidded eyes back to the huge baby gobbling at her tiny maternal breast. As always, CarolAnn gave off an aura of spaced, superior boredom. At the other end of the kitchen table, a guy Gala had never seen before was reading a beat-up copy ofThus Spake Zarathustra,fondling a rampant ginger beard and contemplating CarolAnn’s vacant breast.

Hi, said Gala.

Hey, he replied, then returned his attention to Nietzsche and CarolAnn.

Rainbow Suzi’s shitty nappies were soaking in a tub and stinking out the kitchen. A squadron of empties – Southern Comfort, Jose Cuervo tequila and Newcastle Brown Ale – had colonised a large portion of the kitchen floor.

Dead men, man, said the beardy guy. Dead men standing.

The bin was bulging. In the vegetable rack carrots were growing their own beards and mushrooms were composting themselves.

Breakfast options. Option. Muesli. There was always muesli. The freaks ate the stuff at any time of day or night. CarolAnn subsisted on muesli, alfalfa sprouts and heroin, which kept her waif-like and irresistible to men. There was no milk. No juice. No coffee. No bread, cheese, oatcakes. In the fridge was a glass jar which contained one dill pickle suspended in what looked like pondwater, and two eggs on which somebody had written in felt tip: EAT ME AND DIE. A solitary tea bag lay at the bottom of a rusty caddy. Just the other day Gala had bought a box of fifty, on special offer. Not much of a bargain after all.

Man, this place is honking.

It was Genius Jake, bringing into the kitchen his own honk of unwashed clothes. Though Jake took frequent, lengthy baths – he liked to soak and chant mantras, and fancy he was raising himself onto a higher plane of consciousness – he considered it too much hassle to launder his lumberjack shirts and elephant cords.

Genius Jake was so called because he had rigged the electricity meter so the pad had free, unlimited, illegal power, and because he could string sentences together long after everybody else had succumbed to a dope-induced stupor. The previous night, temple balls and Thai sticks had been doing the rounds and Gala’s brain felt like a sock stuffed down the back of a mouldering couch.

What’s up, kid? said Jake. You look so totally straight today.

Meeting the parents.

Gala was wearing the skirt and jacket, tan tights and sensible shoes she normally reserved for job interviews, which, she hoped, gave as little away about her lifestyle as possible.

Bummer, said Jake. You should take ’em to Fat Kitty’s. Blow their mind.