Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Rough Trade Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Rough Trade Edition

- Sprache: Englisch

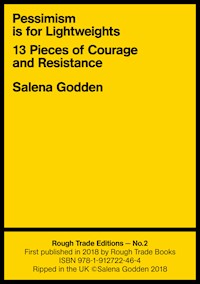

A collection of 13 pieces of courage and resistance, this is work inspired by protests and rallies. Poems written for the women's march, for women's empowerment and amplification, poems that salute people fighting for justice, poems on sexism and racism, class discrimination, period poverty and homelessness, immigration and identity. This work reminds us that Courage is a Muscle, it also contains a letter from the spirit of Hope herself, because as the title suggests, Pessimism is for Lightweights.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 49

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Pessimism is for Lightweights

30 Pieces of Courage and Resistance

Salena Godden

Dedication

Foreword by John Higgs

Welcome to Hope

Pink Moon

Soup

Courage is a Muscle

It’s All About the Pathways

I Saw Goody Proctor Jogging Without a Face Mask

The Day We Stopped

No Holds Barred

Not Every Thing is True

So, This is How it Starts in Books

Point Nemo

Chapter

Gentle Reminder

Insert

Sorry to Trouble You

Who is Us, Who is Them

RED

Ortolan

Old Blood and Young Teeth

Christine

Sushi

The Letter

It Isn’t Punk to Seek Permission

Sage

While Justice Waits

Before You Go

Every Disaster Movie Begins with the Government Ignoring a Scientist

Tomorrow’s Roses

Pessimism is for Lightweights

Pessimism is for Lightweights—Old English Translation by Emily Cotman

This book is dedicated to every person who is using their muscle, their voice, their platform, their work, their art, their time and energy to speak out and stand up for human rights and a better tomorrow. Here are 30 pieces of courage and resistance. Some of these pieces were published in the original pamphlet of ‘13 pieces of courage and resistance’ in 2018. Some pieces I have revised and changed as times are changing and the world is changing. Some of these poems have developed as they were shared and performed at festivals and events. Some of these poems are new and unpublished, some were written as we entered the 2020s and a global pandemic, escalating wars and divisions that would test even the most optimistic and heavyweight among us. Some pieces were inspired by peaceful protest, poems written for people on the front line, pushing for equality, for justice, for peace and freedom. Anti-hate poems. Poems dedicated to people trying to save the NHS. People fighting to save libraries and pubs, the heart of our community and our humanity. People fighting to save the planet. People fighting for justice. This work contains a conversation with the spirit of Hope herself. I thank you, and as always, share these poems with love and solidarity.

Salena Godden

The phrase ‘pessimism is for lightweights’ emerged in the dark days of the mid-Trump era, on 5th May 2017. It arrived as I wrote an email to my friend James Burt. The full sentence was, ‘Pessimism is easier, of course, but pessimism is for lightweights.’

Back then, the world seemed almost impossibly bleak, as per usual. There was light as well as dark, but you would not have known this from the media you consumed. Green energy became cheaper than fossil fuels years earlier than even the most optimistic predictions, to give one important example, which meant that it now cost more to destroy the climate than it did to repair it. This was a profoundly important moment, but it was not one that the algorithms of social media or the business models of traditional media brought to anyone’s attention. They just kept our eyes glued miserably on Trump and Brexit.

I recall feeling let down at the time by a few writers and thinkers I had previously looked up to and seen as wise elders—people I had learnt much from in the past. They shrugged and proclaimed that everything was fucked, and that we were all doomed, and that was all there was to it.

This was a seductive position to adopt, I knew that. You could almost feel a sense of relief when they made it—there was now nothing to be done, so they could relax and do nothing. Once they had adopted this worldview, they had an almost desperate need to protect it and anger would flare up when it was threatened. I felt that if I had shown them a chessboard and asked them to describe it, then they would have looked away and told me I was holding a black square. It was a very strange time. To deny the dark, and to bury your head in the sand and refuse to acknowledge injustice, is generally accepted to be wrong, so I couldn’t understand why acknowledging the existence of light had now become taboo. To give up is a luxury. To give up requires the knowledge that the darkness probably won’t affect you or your daily life too badly, because if it did you’d fight like hell. To give up, then, is the privilege of abandoning others to their fate. It is to wash your hands of your neighbours, and of the coming generation. When I talk here about giving up, of course, I am not talking about having bad days. We all have those. We are all allowed those. To be knocked down on occasion is different to intentionally dropping to the floor.

On a cold-headed, rational level, optimism is a better strategy than pessimism because an optimist will imagine all sorts of solutions to problems when a pessimist will see no point in trying. Here we’re not talking about blind optimism—where you ignore reality and tell yourself that everything will be fine. We are talking about pragmatic optimism. This is where the problem is faced and fully comprehended, and an optimistic outlook is adopted as the best way to deal with it. It is the pragmatic nature of choosing optimism that makes hope so powerful and radical.

I still love the phrase ‘pessimism is for lightweights’. It is a warrior’s phrase, yet it is somehow both spikey and fluffy. I like the journey it has been on over the last five years, and I like wondering about where it will go from here. A culture with a phrase like that in it doesn’t seem quite as hopeless to me as the culture of the mid-Trump years in which it was born. We writers like to kid ourselves that we own the words we produce, and we’re very grateful for the copyright laws that keep up this pretence, but deep down we know that it isn’t true. Words live in as many heads as they can, and their point of origin is irrelevant.