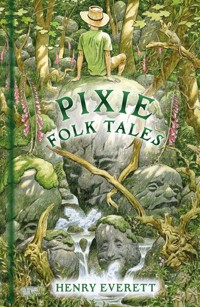

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

Pixies are recognised around the world as mischievous members of the fairy race, but their traditional stories dwell in South West England. Across Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, they have been loved and revered, avoided and feared for centuries. Within these pages, you will find the collected tales of the Pixies, Piskeys, Knockers and Spriggans and many more of their magical kin. Their impish and unpredictable nature can help or hinder us, their human neighbours. Their stories call for playful kindness, magical thinking and careful respect for the living landscape around us. Allow the stories of the Pixies to charm you, rekindle your relationship with the land and embolden your connection to nature. But be warned: these tales are alive with Pixie magic! Expect enchantment and take care as you prepare to enter the wild places of Britain's South West.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text and Photographs © Henry Everett, 2025

Illustrations © David Wyatt, 2025

The right of Henry Everett to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 617 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

Dedicated to my grannie, Poppet Hall.Through her company and garden I knew magic.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

How I Met the Pixies

Who are the Pixies?

The Pixie Collectors

1. The Veil Thins: Meeting the Pixies

Modilla and Podilla

Battle of Pixies and Fairies

Nanny Norrish

The Broken Ped

Fairy Funeral

2. Strange Sights: Neighbourly Relations

Two Moons in May

Two Pixie Threshers

Withypool Dingdongs

Colman Grey

Deal with the Knockers

Tom Trevorrow

3. When the Fen Rises: Pixy-Led

Pixie Lights

Voyage with the Piskies

The Tale of Joan the Wad and Jack O’L

Jan Coo

Tarr Ball and the Farmer

Pixy at the Ockery

4. Alluring Lights: Midnight Mischief

On the Mare’s Neck

Tulip Pixies

No Supper, No Gold!

Fisherman and the Piskeys

5. Circle Magic: Gallitraps and Pixy Rings

Huccaby Courting

At the End of Tresidder Lane

Tom Kiss-the-Leek

Why the Donkey is Safe

Three Little Pixies

6. Trick or Treat: Second Sight

Pixie Bathwater

Faerie Ointment

Ann Jefferies

The Four-Leaf Clover

7. Spirited Away: Into the Otherworld

Cherry of Zennor

Lost Child of St Allen

The Changeling of Brea Vean

Trevilley Cliffs

The Fairy Dwelling at Selena Moor

8. By Pixie Feet: The Hills are Alive!

Origin of the Pixies

The Piskies

Pixie Quartet

Ottery Bells

St Nonna’s Well

That’s Enough to Go on With

9. The Time Has Come: Pixie Reparations

Spriggans of Trencrom Hill

Barker’s Knee

The Woman who Turned her Shift

The Man who Coined his Blood to Gold

Old Farmer Mole

10. When Pixies Meet: The Balance of All Things

King of Pew Tor

Goblin Combe

Fairy Fair

Fairy Fort

Bibliography and Further Reading

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Massive thanks to Nicola Guy at The History Press for trusting me with this project and to David Wyatt for his wonderful illustrations; thank you for bringing these tales to life.

Huge thank you to Lisa Schneidau for her unwavering support, encouragement and wisdom. Thank you to Ronnie Conboy, Sara Hurley and everyone who has shared stories at South Devon Storytellers. Thank you to Sharon Jacksties and Jem Dick for introducing me to Somerset with such warmth, and to Mike and Tina O’Connor for the long hours of most wonderful conversation.

Thank you to John Buckingham, whose love for Nellie Sloggett brought her to life, and to Pete Ward, whose relationship with the land continually inspires me. Thank you to my Pixie friends Lu Christie and Claire Casely and to Holly Ebony for allowing her song to be included in these pages.

This book would not have been possible without Simon Young, Alex Langstone, Rupert White, John Kruse and Jeremy Harte.

Thank you Anna, Bex and Julia for feeding me in the final hours! And thank you to Tim and Jess Graves for giving me time to finish the book.

Dad, Jenny, Romilly, Sam, Tobin, Elowyn, Doug, Neesha, Poppie, Pippin and Pooka. I love you.

To each Pixie that lured me!

To each place that held me!

To each story that fed me!

HOW I MET THE PIXIES

I was lucky enough to grow up surrounded by fields on the edge of a village on Dartmoor. My siblings and I played outside for hours at a time. We made dens in the tall grass and base camps beneath the trees and followed paths in the hedges. We walked the old lanes along rivers filled with mossy boulders and explored the open moor.

I left the country to go to university, then moved to the city. More than a decade later, during a year in Australia, I was reminded with ferocity how alive the earth really is. Australia is loud! In bird and insect, stone and water. In colour, temperature, mass and volume. It blew me away.

I was introduced to the artwork and traditional stories of the First Nations people. Although I do not profess to comprehend the depth of their visual and cultural narrative, I was amazed how both felt alive with spirit. So much so, that it felt part of the living landscape.

I returned to England not sure I had ever seen anything of British traditional culture that felt as deep or in harmony with the land as I had seen in Australia.

What were the traditional stories of my home? Had we sold it all under capitalism? Is this why our western world is so fragmented from the environment? Is this how we have come to be facing environmental collapse?

I returned to Devon, to the village I grew up in. I walked extensively and discovered something amazing one day. On Dartmoor, I walked past a puddle that had submerged stones in it. On a whim of fancy, I thought it looked like a dragon’s nest. That evening, by chance, I met storyteller Sara Hurley. I told her about the dragon’s nest and she told me that I must already know the legend of the dragon from that part of the moor; I did not. Funnily enough, the story was of a man who found a dragon’s nest just a mile from where I had been. I became obsessed with this story and the idea that perhaps the land really does want us to engage with it. To step into our imaginations and … listen! To give it personhood, to treat it with respect and offer it our service.

Sara invited me to South Devon Storytellers, a local story circle, where traditional stories are shared informally. I was enchanted by performance storytellers who breathed life into old tales. The room came to life and my imagination transported me across landscapes, into the depths of magic, danger and wisdom, before returning me back into my body again. I had been writing stories and poems for a few years, but I had never experienced story like this. These stories were medicines of adventure, wisdom and knowledge, surprise, wonder and fun. They shone a light on to what I was looking for.

As a teenager, Faeries by Brian Froud and Alan Lee had a profound influence on me, as I sought out stories of the land, I returned to the Fae. Pixies have always been my local mischievous characters, hiding in the hills. I knew their mischief, but I didn’t know their stories. So I started looking. It felt like the Pixies heard my longing to meet the land and their tales.

So began many adventures across Dartmoor, wider Devon, Cornwall and Somerset. As I delved into stories and places, Lisa Schneidau taught me that if you want to learn a story, ‘walk with it’. It feels to me that stories really live outside, held between people and place. Outside you can meet the mystery of being, internally and externally. In this way, I started walking with the Pixies.

Pareidolia is the term given to the tendency to perceive patterns or images in random or ambiguous stimuli. Whilst exploring the places where the Pixie tales herald from, I caught endless glimpses of smiling faces in stones, in the leaves of trees or floating on the river surface. Every glimpse felt like I had discovered a Pixie treasure and made my adventures feel even more mischievous and playful, so within these pages I have included many of my own photographs of these ‘Pixie treasures’. It is a glorious reminder that the way we see the world defines how we colour our experience. Our imagination truly is a gateway – if you look for magic, the face of magic will look for you!

The book in your hands has been a magical adventure. The stories have had a profound effect upon me. I am retelling them to you, so that they can spread their magic and enchant your story. But let us not forget the generations of people who have passed on these stories; their words are not forgotten.

Because the folk tale is an inherited cultural tradition, I have focused on folk tales for this volume. I am leaving out many authored tales, and, aside from some exceptions, personal accounts, which are both fascinating and illuminating. For anyone interested in further reading, I have included a bibliography and reading list.

But, a warning. Something serious. Be aware.

The book in your hands is filled with pages of the enchantments of the Pixies. These beings want to dance into your imagination. They will call you to the magic that awaits, inside and outside. Be warned, they are experts at leading people astray. They will laugh and they will clap when they lead you into boggy terrain. Be careful how you go.

This book is aimed at adults. I advise caution before opening a story at random and reading it to a child.

The Pixies’ stories have changed my life … do not think they won’t do the same for you.

Expect enchantment!

WHO ARE THE PIXIES?

Pixies and Fairies are creatures we meet either by extraordinary encounter, or through story. Pixie and Fairy are often interchangeable terms in modern society. What are the boundaries between them? What defines one from the other?

In 1953, Disney created some confusion with his depiction of Tinkerbell in his animated version of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. The story started as a play in 1904 and became a book in 1911. Tinkerbell had been written as a Fairy; the idea she was a Pixie did not come along until Disney released his film.

All it takes is faith and trust, oh and something I forgot! Dust! Just a little bit of Pixie dust!

Peter Pan, Disney (1953)

In the film, Tinkerbell is referred to as a Pixie by Wendy, Michael, Hook and Smee. Peter tells the children that Tink’s ‘Pixie Dust’, will give them the ability to fly. To confuse the matter further, Disney designed Tinkerbell as a typical-looking Fairy. The release of Peter Pan was significantly delayed, but the concept drawings of Tinkerbell were envisioned as early as 1935, while the Blue Fairy (of Pinocchio, 1940) and Sugar Plum Fairies (of Fantasia, 1940) were in studio production.

However, we cannot blame Disney entirely. Georgian and Victorian depictions of Fairies were rife with small-winged spirits. In his 1793 poem ‘Song of the Pixies’, Samuel Taylor Coleridge described his spirits with ‘filmy pinion’ (insect-like wings). Since Shakespeare, depictions of Fairies have taken whatever image suits the audience at the time. Shakespeare was the first to miniaturise Fairies. To add to the problem, Fairy can refer to an individual, but it can also be used as an umbrella term to refer to a wide range of magical beings.

To understand what makes a Pixie, we must visit the sources of their folk legend, which takes us to South West England. In the folk collections of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset we find the surviving folk tales of the Pixies.

As we will see in ‘Battle of Pixies and Fairies’, Pixies claimed the territory of ‘Pixieland’ as everything west of the River Parrett to Land’s End. Within this boundary, the majority of Pixie stories are to be found.

Piskey, Pisgie, Pixie, Pigsey, Pixey and Pixy are all used. In their stories, I have used the spelling we find in their original sources, but I use Pixie throughout for simplicity. I have chosen to capitalise their names to honour their personhood.

Some folklorists have insisted that there are clear differences and identifiable types of Pixie within the South West. What defines a Pixie, it seems, has always been up for debate. However, these characteristics are worth noting.

As we begin this journey, it is only proper and polite for me to introduce you to the magical folk you can expect to meet along our adventure.

Welcome to Pixieland.

Pixies or Pigsies (sometimes Piskies)

West Country Fairies are usually depicted as elven beings of the hobgoblin family. Usually wearing green, naked or dressed as a bundle of rags. Often found in Somerset with red hair and squinty eyes, sometimes wearing red caps. Lovers of music and dancing, water and solitary places. Generally depicted standing anywhere between eight inches to three feet tall, occasionally human size.

Particularly fond of misleading travellers, stealing horses and riding them in circles.

Sometimes explained as souls of heathens, not permitted entry into heaven, or as souls of infants who died before baptism (Bray, Vol. 1, 1836, p.172).

Piskeys

The Cornish Piskey is similar to the Pixie in Somerset and Devon.

Hunt believed Piskeys belonged to an older family than those in Devonshire. Katherine Briggs agreed, stating the Cornish Piskey is ‘older, more wizened and meagre than the sturdy, earth Pixies of Somerset and the white, slight, naked Pixies of Devon.’ (Briggs, 1976, p.328)

Knockers

Knockers are found working in Cornish mines; they are often male, diminished characters, usually with beards. Some believed they were the souls of Jews, eternally bound to work in the mines for a supposed role in the crucifixion.

Imps, Gathorns, Buccas, Nickers, Nuggies and Spriggans are all names used to describe those who frequent Cornish mines (Wright, 1914, p.199).

Spriggans

Spriggans are known as the most dangerous spirits in Cornwall. Often referred to as grotesque with crooked features, the sight of a Spriggan was said to be terrifying. Spriggans are thieves who hoard stolen treasure; they are even responsible for stealing children and leaving changelings. Bottrell tells us they could blight crops and create whirlwinds to make mischief. Hunt tells us they are the spirits of Giants who have diminished. When angered they can grow to Giant proportions to frighten intruders. Because of this, they are also seen as guardians of the Piskey doors.

Bucca

Possibly related to Pooka (Ireland) and Pwcca (Wales), Bucca is a shapeshifter, sometimes appearing as a black buck goat, an aquatic being, or a mining spirit. Bucca appears frequently in West Penwith. Botterell referred to Bucca as an ‘ancient divinity’.

‘Fisherman left a portion of their catch on the sand for Bucca, and in harvest a piece of bread at lunch-time was thrown over the left shoulder, and a few drops of beer spilt on the ground for him, to ensure good luck.’ (Courtney, 1890, p.129)

People referred to Bucca Gwidder (white) and Bucca Dhu/Boo (black), the former benevolent, the latter malevolent. Bucca Boo became synonymous with the devil, and in some tales appears as Old Nick. Bucca can also mean ‘fool’.

The Small People/The Little Folk/Pobel Vean

The Small People are thought to be the spirits of ancestors who inhabited Cornwall long ago. According to Hunt, the Small People are spirits who were not allowed to inherit ‘the joys of heaven’, (because they lived pre-Christ) but were too good to be condemned to the ‘eternal fires’. They diminish in size every year, until they are the size of ‘muryans’ (ants), at which point they disappear entirely.

Mostly peaceful, they are found all over Cornwall, especially between Penzance and St Just. They can sometimes be benevolent, especially when they discover oppressed poverty. Their help is given freely but, if their assistance is gloated about or shared unfairly, they become angry and their help is taken away. They are wary of humans and withdraw when they sense we are near.

Jack O’Lantern/Jacky Lantern

West Country name for Will-o’-the-Wisp. Jack is a lantern-bearing Fairy who lures unwary travellers astray. He appears as a disembodied flame, sometimes known as a Spunky or Piskey. In some places, he is Pixie King.

Joan the Wad

Queen of the Cornish Piskies, ‘Wad’ meaning torch/bundle of straw. Joan is often depicted naked. She has a very mischievous nature, but is best known as a good luck charm, bringing health, wealth and happiness to anyone who carries her image. ‘Good fortune will nod, if you carry upon you Joan the Wad.’

Spunkies

The Spunkies are believed to be the souls of unbaptised children who act as psychopomps, leading the ghosts of the dead to their final passing place. Spunkies are said to wander the land until Judgement Day (Tongue, 1964, p.94).

Corpse Candles

Corpse candles are spectral light that come with a forewarning of death.

Ruth Tongue records a Somerset woman who saw a floating light move towards a sick woman’s cottage door. An hour later she was dead. (Tongue, 1964, p.93)

Derricks

Described as dwarfish spirits of ‘somewhat evil nature’ in Devon (Wright, 1914, p.206).

They have a better reputation in Hampshire, where they might help locate a lost traveller. Their traditional tales are hard to find, but depicted best in modern Fairy story ‘The Derrick’ by John Kruse.

Collepixie/Colt Pixey

Thought to be separate from the Pixie family, but sharing their name, the Collepixie is also a trickster, known in and around the New Forest, Hampshire. It is said to take the form of a pony to lure other ponies and travellers deep into the marshy bog to the barrow known as ‘Cold Pixie Cave’.

Across the New Forest, the name of the Colt Pixey is interchangeable with Puck and Pooka. This is evident in local place names: Pixey Mead, Picksmoor and Puck Piece. The oldest written reference to any kind of Pixie is Collepixie, featured in Nicholas Udall’s translation of Apophthegmes:

‘I shall be ready at your elbow to play the part of a hobgoblin or collepixie and make thee fear the devil is at your head.’ (Apophthegmes, 1542).

THE PIXIE COLLECTORS

Anna Eliza Bray (1790–1883)Collected tales from Dartmoor

Anna Eliza Bray is a key character in the story of the Pixies. Through her writing the Pixies became identified in their own right among British Fairylore.

Bray was a prolific writer and best-selling author during the Victorian period. While in Tavistock, Devon, she published various historical novels and wrote extensive letters describing the history and customs of the town to then poet laureate Robert Southey. The letters, which contained Pixie stories she heard from maidservant Mary Colling, were published in three volumes in 1836: Traditions, Legends, and Superstitions of Devonshire.

Bray’s books were popular and sold well. The tales of the Pixies caught the imagination of the dawning Victorian era. It is important to note that Bray was influenced by Fairies in wider British literature (Drayton, Shakespeare, Fosbroke, Jonson), which informed her depiction of the Pixies.

Bray received more and more interest in the Pixies, which encouraged her to author a volume of stories inspired by their folklore, Peep at the Pixies (1854). Bray’s cousin, Christina Rossetti, was inspired by this collection to write her incredible poem ‘Goblin Market’ in 1859.

Mary Maria Colling (1804–53)Collected tales from Dartmoor

Mary Maria Colling was the maid servant who told Bray the Pixie stories that were included in her popular work. Colling was a poet and showed her work to Bray who, with Southey, helped Colling publish her work in Fables and Other Pieces in Verse (1831). Bray wrote a lengthy introduction to Colling’s poetry book, making the class difference between them ever evident. Without Colling, an important part of the Pixies story would never have happened.

Robert Hunt (1807–87) Collected tales from Cornwall, particularly West Penwith

Robert Hunt was a mineralogist who lectured in mechanical science and contributed a great deal to British mining. He was also an early photographer and antiquarian and passionate about folklore.

Hunt’s collection Popular Romances of the West of England (1865) was very well received and remains a key text for historical sources on Cornish folklore. Hunt collected some of the tales in his book but had informants across the county who supplied him with content. He acknowledges his two key sources as Thomas Quiller-Couch and William Bottrell.

Hunt was clear that the Cornish Piskey was different from Bray’s depiction of a Devon Pixie, which he called a ‘harmless creation … rollicking life amidst the luxuriant scenes …’ Cornish Piskies, on the other hand, had ‘their wits sharpened by their necessities’ (Hunt, 1865, p.80).

He was a passionate advocate for the taxonomy of Fairies and identified five types of Spirits in Cornwall: 1. The Small People, 2. Spriggans, 3. Piskies, or Pigsies, 4. Bucca, Bockles or Knockers, 5. Browneys. Unfortunately, Hunt gives just a brief reference to the Browney in the South West, and as this is the only reference they do not feature further in this book.

William Bottrell (1816–81) Collected tales from Cornwall, particularly West Penwith

William Bottrell was born at Raftra, near Land’s End. His father was William Vingoe Bottrell and his mother was Margaret Bosence. (Vingoe, Bottrell and Bosence are all names you will find through his recorded tales). His family, particularly his ‘Grandmother Mary’, shared many stories with him from an early age, which he worked into his written stories later in life.

Bottrell married, travelled and worked abroad, but returned to Cornwall a poor widower. He lived in a shack on some land at Hawke’s point, Lelant, with a black cat called Spriggans, a cow and a pony.

He shared up to fifty stories with Robert Hunt, who published them in his Popular Romances in 1865. Encouraged to publish his own, Bottrell spent the last years of his life writing up stories, referring to himself as ‘The Old Celt’. Bottrell published articles in periodicals and two volumes of his bestseller Traditions and Hearthside Stories of West Cornwall in 1870. He was working on a third when he died, and this was later published with help of Rev. W.S. Lach-Szyrma.

William Crossing (1847–1928) Collected tales from Dartmoor

Crossing was a leading authority on Dartmoor and its antiquities. Born in Plymouth, he started exploring Dartmoor from an early age. He was a dauntless walker, relentlessly exploring the moor in all weathers. He was passionate about preserving its history and helped re-erect many of the ancient stone crosses that were being used as gateposts.

Importantly for us, Crossing collected and published Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies in 1890 while he was living in South Brent. He was well liked and respected by the folk across Dartmoor. He saw great value in their tales and the amount he collected perhaps reflects their confidence in him too. The book remains an invaluable record of Pixie folklore from Dartmoor.

Crossing is best known for his 1909 Guide to Dartmoor, which contained extensive and detailed descriptions of Dartmoor’s landscape. He and his wife struggled to survive on their modest income and Crossing’s health was affected by chronic rheumatism in his later years.

Jonathan Couch (1789–1870), Thomas Quiller-Couch (1826–84), Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch (1863–1944)Collected tales from Polperro, Cornwall

Jonathan Couch was born in Polperro and after studying medicine returned to the village to take the position of local doctor. He was a great naturalist with wide-ranging interests. Perhaps naturally for someone who lived in a fishing village, he was interested in fish. Local fishermen brought him specimens from the water, which he studied and painted meticulously. His magnum opus, History of the Fishes of the British Isles, was completed in four volumes in 1865. A species of goby fish, Gobius couchi (Couch’s goby), was named after him.

During his lifetime Couch collected the customs and antiquities of the people of Polperro, including a range of historically important Fairy mythology. He compiled and collected his research into The History of Polperro, which remained a manuscript on his death in 1870.

His son, Thomas Quiller-Couch, edited and added to the manuscript, publishing it in 1871. Quiller-Couch was also a doctor, folklorist and writer. He wrote repeatedly for Notes and Queries and the Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, and importantly was one of the key contributors of folklore and stories to Robert Hunt. Thomas’s son, Arthur, became a prolific writer and literary critic himself, sometimes publishing under the pseudonym Q. All three members of this extraordinary family have influenced the pages of this book.

Nellie Sloggett/Enys Tregarthen (1850–1923)Collected tales around Padstow

Nellie Sloggett was native to Padstow where she spent her whole life. When she was 16, she suffered an illness that left her paralysed. Bedridden for the rest of her life, Sloggett found freedom in stories, books and writing.

During her lifetime she became a prolific writer and published at least eighteen books, at first under Nellie Cornwall and later as Enys Tregarthen. She published The Piskey-Purse (1905) and North Cornwall Fairies and Legends (1906), both containing authored stories heavily inspired by Cornish folklore and traditional motifs. Because there were very few collectors of folklore on Cornwall’s north coast, her work provides an invaluable resource.

Sloggett wrote many characterful tales of the Pixies, always containing sparkling descriptions of the landscape. American writer Elizabeth Yates befriended Sloggett towards the end of her life and collected many of her Pixie tales into Pixie Folklore and Legends, published posthumously in 1940.

Ruth Lyndon Tongue (1898–1981)Collected tales from Somerset

Ruth Tongue was a storyteller, writer and collector of folklore. She was a magical character and an important collector of Pixie stories, particularly from Somerset.

Born to a middle-class family, Tongue spent some of her early childhood in Taunton before returning to Somerset later in life. She was a natural storyteller and her contribution to British folklore remains extensive.

She developed a keen friendship with Katherine Briggs, one of the most influential British folklorists. Tongue shared many stories, quotes and folklore that Briggs included in her collections. Together they published Folktales of England in 1965.

Today, Tongue is a controversial figure in folklore. She suffered multiple house fires and lost many of her written records. She depended on her memory for a lot of her work. Many academics have called into question the reliability of her sources and authenticity of her narrative. Her stories have her own enchanting and colourful style. The debate remains how much she embellished and embroidered or fabricated tales that she called traditional.

1

THE VEIL THINS:MEETING THE PIXIES

To meet the Pixies, we must step into the landscape of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset and meet the ancient stories that have defined it: the dance of water and stone.

Somerset has some of the oldest-known rocks in England, dating back around 440 million years ago to the Silurian period. This was a key time in the earth’s history, when plants, fungi and arthropods were diversifying and establishing life on its surface.

Around 400 million years ago, the Devonian period followed, covering areas of the South West in a vast shallow sea with coral reefs and volcanic activity. The sandstone, mudstone, limestone and shale we walk on today are remnants from this time. Some 120 million years later, much of the mudstone was baked into slate and thrust into the sky in a period of mountain building. A giant body of subterranean magma intruded beneath the ground, from a colossal chamber called the Cornelian batholith.

Over millions of years, the Cornelian batholith cooled into a great body of granite, stretching over Devon, Cornwall and beyond the Isles of Scilly. The intrusion left the area rich in minerals, particularly cassiterite, copper, lead and china clay. Millions of years and multiple ice ages later, the mountains were weathered away, finally revealing the granite body that continues to define much of the landscape we encounter today.

Around 11,700 years ago, the most recent Ice Age began to retreat. Sea levels rose as the climate defrosted. The region was then shaped by Britain’s temperate climate.

This was the landscape that our early ancestors explored, first as moving tribes, then settling, erecting stone monuments, in circles, rows, menhirs and field boundaries. Some of these ancient remnants are funerary sites, others are mysteries. Over the past 4,000 years, miners have sought the rich materials the area has to offer. Home to Celtic Britons, the landscape became known as Dumnonia. The region became smaller and smaller as the Saxons encroached. The ancient people were pushed further and further west. Is this why West Penwith remains filled with stories?

As the Industrial Revolution pulled more people toward cities, stories changed and many stopped being shared. Some tales were recorded in the nineteenth century by enthusiastic folklorists. Coloured by their own intention and bias, these folklorists recorded the traditional tales of the country folk, preserving them in the pages of history.

MODILLA AND PODILLA

Dartmoor, Devon

Our journey into Pixieland begins in South Brent, Devon. Located in the wettest, southern edge of Dartmoor, the moorland village is nestled between the River Avon and the slopes of Brent Hill. The village was mentioned in Domesday Book of 1066, but the prehistoric enclosure of Ryder’s Rings at Shipley Bridge show people have called Brent home since the Bronze Age.

Today the village has a vibrant community, environmentally concerned and active in sustainable futures. I grew up in Brent, and am still fascinated by the magical pathways around the village that lead you out on to the open moor.

Our first story was collected by William Crossing, who lived in Brent while he collected and compiled Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies (1890). This was one of the first stories that introduced me to the enchantment of the Pixies, so it feels fitting that this is where we begin our adventure.

A long time ago, before my time but not lost to time, there was an old lady who lived in the village of Brent.

She didn’t have any children or grandchildren, but everyone called her Grandma Partridge. She was a real local character and held in high regard by all, which is why the village referred to her so affectionately.

Grandma Partridge seemed to enchant every conversation or chore into something special. Her cottage garden was filled with colour, and the children of the village would even call round after school to see if she needed any help.

They would put out or bring in her washing or even weed between her flower beds, because once Grandmother Partridge got talking, magic was never far away.

She had curious names for the flowers. She called the honesty flower ‘money-in-both-pockets’ – You’ll see why when they try to seed!

Purple fuchsias she called ‘ladies’ eardrops’ and the wood sorrel at the gate was always ‘cuckoo’s bread’. She told the children to take care with the stitchwort. ‘Don’t pull up any of that! That’s the Pixies’ favourite flower.’

When they were done, they would put the waste on the compost pile.

‘Keep an eye out,’ she would say. ‘There’s a dragon in there!’

And sure enough, on the luckiest days, the children would glimpse a lazy slow worm basking atop the warm pile.

One sunny day in June, Grandma Partridge poured some tea for her little helpers and they asked her for a story.

‘What names do the Pixies call each other?’ one child asked.

Grandma Partridge’s eyes sparkled.

‘Well, I don’t know if it was their names, or what it was, but this is what happened the first and only time I ever saw the Pixies …

‘I must have been about your age,’ began Grandma Partridge. ‘I was just a girl when my family farmed on the edge of Brent …’

It was a freezing winter, the ground was hard as ice, and the trees all dusted with white. A young Grandma Partridge was working in the kitchen with her mother and sister. Meanwhile, her father was in the fields, mending the old stone walls. Now this day was special – it was her father’s birthday – so whilst he toiled away, the three women were secretly making ready a surprise feast!

The family had been on rations since Christmas, so the feast was exciting for all! A joint of meat had been held back for the occasion and was turning on the spit by the fire. The fat was beginning to bubble and burst and the room was filling with the most delicious smell.

Her mother was making a ginger cake (Father’s favourite) and a punch for the celebration. The sisters were busy peeling potatoes, carrots and parsnips.

The three of them poured love into what they were doing, and as they worked, fell into a meditative silence.

‘That’s when it began!’ said Grandma Partridge with glee in her voice and sparkle in her eyes.

At that moment, the door came off the latch and opened, just an inch. They felt the January breeze blow in, and all turned, expecting to see the dog at the door…

Each of them was amazed, for in the crack of the door stood the tiny figure of a Pixie.

None of them had ever seen a Pixie before, but you don’t mistake it when you see one!