Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

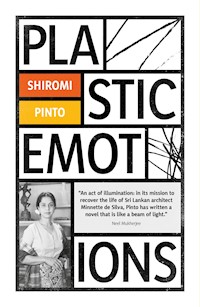

Plastic Emotions is inspired by the life of Minnette de Silva – a forgotten feminist icon and one of the most important figures of twentieth century architecture. In a gripping and lyrical story, Shiromi Pinto paints a complex picture of de Silva, charting her affair with infamous Swiss modernist Le Corbusier and her efforts to build an independent Sri Lanka that slowly heads towards political and social turmoil. Moving between London, Chandigarh, Colombo, Paris, and Kandy, Plastic Emotions explores the life of a young, trailblazing South Asian woman at a time of great turbulence across the globe.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 541

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Plastic Emotions

Plastic Emotions

Shiromi Pinto

Influx Press2019

Published by Influx Press

49 Green Lanes, London, N16 9BU

www.influxpress.com / @InfluxPress

All rights reserved. © Shiromi Pinto, 2019

Copyright of the text rests with the author.

The right of Shiromi Pinto to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Influx Press.

First edition 2019. Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd., St Ives plc.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-910312-31-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-910312-32-2

Editor: Kit Caless, Assistant Editor: Sanya Semakula

Proofreader: Momus Editorial, Cover art and design: Austin Burke

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner.

for L.

‘The Architect, by his arrangement of forms, realizes an order which is a pure creation of his spirit; by forms and shapes he affects our senses to an acute degree, and provokes plastic emotions.’

—Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture

‘… the revolution which had aimed at the destruction of a formalized past resulted in the creation of sterile architecture, beautiful in its use of modern materials and construction but lacking the essential element of contact with the people and their regional life.’

—Minnette de Silva, 1998

Prologue

8 December 2005

‘Christ it’s hot,’ mutters the student, and blows into her shirt. It’s early morning – too early perhaps to undo the top buttons and loosen her collar. She undoes them anyway. At least she won’t be visiting any temples today. Yesterday’s trip to the white Buddha began with the ticket lady reaching over unbidden and buttoning her blouse up to the neck. ‘Annuh hari’, she had said, and smiled.

The student is outside the train station, ready to leave this town for the capital. But she has one more thing to do before she can go. She scans the parking lot for a trishaw, ignoring those with ripped open seats or rusty chassis. She wonders at her audacity – an audacity that spirits her into a glorified motorbike with all the protective reinforcement of a tomato tin.

After some minutes, she settles on a clean-looking specimen. Its car is lime green, the seat is intact and the driver wears a well ironed shirt over a tartan sarong. She asks him if he knows the house and he tilts his head from side to side. ‘Hoyaganne puluwang-dha?’ she asks in halting Sinhala. His head bobs left and right again, and they set off.

The heat builds as they make their way upward. This is one thing they know for certain – that the house is on top of a hill. They know the name of the road: George de Silva Mawatha, after the architect’s father.

The young woman nestles inside the trishaw, peering at the roadside stalls, the cyclists, the thickening greenery. She wonders whether they will find the house, and if they do, what they will find there. She has only seen it in books – Nell Cottage.

She has seen one of the architect’s first builds here in this town. A villa on a different hill, with a sweeping staircase and floor-to-ceiling windows. The view from those windows is stunning, taking in the lake at the centre of the town and the gentle slope of the surrounding hills. Yet the villa is in an appalling state, so much so that the people living in it plead with her, a student of architecture, to buy and restore it. She thinks she would, if she had the money.

The student and the trishaw driver have been climbing now for the last forty minutes, the three-wheeler fretting and moaning up the steep path. The driver keeps stopping and jumping out to look at the house numbers. He waylays passing pedestrians who either shrug or point upward. So they continue. Eventually, they find numbers 13 and 15, but 14 – the one they’re after – has vanished.

She wonders if this isn’t some kind of trick the architect is playing on them. Her houses are often to be found camouflaged by greenery. Perhaps Nell Cottage is right in front of them, if only they knew which branch to raise, which grasses to part.

The architect was prone to tricks of all kinds, thinks the student. She remembers a story she once heard: how, when the architect was older and living in London, she called a student, much like her, to her flat in the middle of the night. Her panicked voice had been enough to propel him from bed and onto the tube. ‘Listen,’ she had said as he walked in, rubbing her cheeks so that he, too, could hear it: the thin hiss of aging skin. He ran to the chemist to buy her face cream.

The trishaw driver stops to inquire at a garage. The mechanic there tells them to keep going to the very top of the hill. The road jolts them left and right. Whole shovels-full of asphalt have been scooped out by hard rains. As they continue upward, they pass a gas meter reader who, fortuitously, has just come from the cottage.

‘Okoma kadila,’ he says. Then, addressing the trishaw driver he adds, ‘Thaniying yanna dhenna epa.’

The young woman bristles at the man’s cautionary directive, then accepts it. She and the trishaw driver continue a little further until they find the cottage’s elderly caretaker. Even at this early hour, his breath smells of toddy and his legs are unsteady. He seems irritated at the intrusion and frowns. Worried he will turn them away, she smiles. She wishes she had a bottle of something to bribe him with, but her fears are refuted. He beckons to them and lets them in.

They enter the grounds of Nell Cottage and she is astonished. The pergola still drips with red bougainvillea, although some of its brick columns have crumbled into the grass. The entrance to the house is magnificent, its wall covered in square terracotta tiles with Kandyan dancers sculpted in relief on each one.

Yet the front garden has been uprooted by wild pigs. And as she steps inside the house, she sees that the cottage has been gutted by the rains. The ceiling has caved in, the floor strewn with glass shards, glinting now like thousands of fallen stars.

‘Balagana,’ says the caretaker, and he puts out an arm to keep her back. She scans what’s left of the living room, its floor now a pulpy mess. Leaves of paper are scattered everywhere. The bespoke shelves that the architect had built, once orderly and chic, have collapsed like a stack of wet crackers. Sodden plans stick to an equally sodden desk.

Ivy has taken root on the splintered walls, trailing across the floor, leading their gaze deeper into the house. The hallway is part jungle, part ancient ruin. Halfway in, a lone slipper lies upside down, as if cast off by an impatient foot. The house is at once desolate and richly fertile.

The student’s thoughts return to the villa on the hill. She thinks it, too, will succumb once the people living there leave. If not succumb, then the inevitable drive to modernise this town, this country, will see the villa razed to the ground to make way for another hotel. Again, she regrets coming here with no money, no plan, nothing but her need to know.

They pick their way forward, through the remains of unidentifiable rooms. A small bird flies in as if from nowhere, and is immediately swallowed up by green. Wherever they look, they find a mix of unconnected materials: pages torn from magazines, melting photographs, broken plates, a muddy cushion, unopen letters. An absence of clues to the function of this part of the cottage disorients them. But their confusion is soon righted a few paces on.

The student is the first to see it: a white bathtub, now mossy and overflowing with ivy. This once elegant, claw-footed tub is the source of the profusion of green swallowing up Nell Cottage. Or so it seems to her.

‘Kavuruth nona-ve visit keray ne,’ says the caretaker. ‘Vasa hindha.’ He tells them the architect fell while getting out of the bathtub, and lay on the floor for days before anyone found her. She died later in hospital, remembered by no one.

The student imagines the architect curled like a gecko on the ground. And before that, sitting in Nell Cottage, stern and lonely in her old age. She never married, had no children. The student thinks of her, drawing up plans while dreaming of the man she loved. ‘Le Corbusier was a tall man,’ the architect had once said.

And as she takes a last look inside the house, the student glimpses a younger architect, designing, building, creating – holding her lover behind her eyes until the very end of her days.

I

May – June 1949

London

28 May 1949

Corbu. Corbu. Corbu. You would have thought me mad, writing your name so many times in my diary like a forgerer practising her craft. In the writing comes reality – the reality of you: cutting the page with black ink, as bold as you were when I first met you. Funny, too. There is something in the way that you write your name. That flourish that functions as a wink. It is there in your drawings – those strangely imprecise scratchings that grow more certain as the pages turn. How I long for that certainty now. The certainty of you. Who else can sustain me now that everything is over?

Papa has cut me off. He wants me back in Ceylon immediately. He said he will not pay for any more studies. Enough is enough, he wrote. You will come home now. Independence, you see. Papa wants me back to claim my place in a new Ceylon. He also wants to keep an eye on me. To make sure I don’t fall down some louche hole in Europe. You have been loafing about long enough, he wrote. It is time to work.

And what else have I been doing here if not working? How else did I make ARIBA? Yes, Corbu, I’ve done it. I, Minnette de Silva, have been elected an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. I – who had been giddy with London when I first arrived, spending too much time in the pub and not enough of it on my portfolio. I stand before you now – before everyone – as the first Oriental woman ever to have made ARIBA. Doesn’t the fact of this distinction mean anything to dear old pater?

It’s early, Corbu. A pale light shivers through my bare windows. Still no curtains. Marcia continues to be appalled, but I prefer it this way. From up here, I can watch London – say a slow goodbye.

How it has changed. When I first arrived, there were planes ripping open the sky. People were remembering the Battle of Britain, still celebrating the end of the war. Never mind that the city was half in ruins, it was as if hope itself would clear up the mess. But a few days later, everything returned to normal. People climbed back into themselves and stuttered about looking harried and glum. The city was depressed, most of it bombed out and clouded in soot. No amount of hope could undo that.

London was a disaster. My search for this flat took me through so many half-torn streets; so many houses destroyed in the war. I would turn down a road, be heartened by the proud line of a Georgian terrace, only to find it collapsing to one side like the face of a stroke victim. By the time I came to Savile Row, I’d resigned myself to living in less than ideal conditions – far less ideal than my hilltop lodge in Kandy or my beloved rooms in Bombay. I climbed that steep staircase, telling myself that I would have to take it whatever its faults. But this flat nestled high above Savile Row, with its dear sloping floors, made itself mine. The windows were still covered in black-out paper and the rooms quiet – as if they’d all been holding their breath until I arrived.

Sitting here watching the sun perfume the clouds, I remember the moment I stripped that paper off the windows, the dust puffing into the air, black crumbs catching in my fingernails, and then the view: Berkeley Square six blocks off but no less splendid. That was my reason for eschewing curtains, Corbu: Berkeley Square. And when I invited my AA friends round we would wander over to this window and stare out at that green patch, feed on its geometry, and talk about Gropius and Bauhaus, Frank Lloyd Wright and that man, Le Corbusier.

Even Marcia and Werner love this place. In their eyes, it was the first proper thing I had done since my arrival – and this was saying a lot given I’d been here a few months already. Of course, I immediately squandered the moral credit I’d gained by throwing one party after another until the congratulatory allowance that Papa and Amma sent me was gone. We had everything: champagne secreted from the college, bananas off the black market, petit fours, Victoria sponges.

Marcia and Werner came, tutted over my profligacy and drank tea (well, my sister did; Werner can’t resist the whiskey). Mimi was there, too, causing Marcia to blanche with her purple language and shameless deportment with the boys. Honestly, Corbu, I don’t know when my sister turned into this caricature of herself. She certainly wasn’t like this in Bombay. Those were brilliant times. I’ll admit my attic flat pales rather next to Jassim House and its breezes surfing in over the Arabian Sea, delivering little Zubin’s violin practice through my windows each morning. Now, no more.

But then there were your visits here (of which Marcia and Werner shall remain ignorant). They more than anything else are what have made this place my home – our home. Yes, Corbu, I think of this flat – which has been my atelier for these last four years – as ours. I think of you huffing up those fragile steps, damning the English for their poor calculations as you bump your head yet again on the underside of a step, and I want to cry. How can I leave all this? I have one month – just one month left. It’s too soon.

You must come here, Corbu. Visit me once more at my penthouse flat. Stand here and hold me to your heart.

Ton oiseau

Minnette

30 May 1949

London

I’m just back from lunch with Mimi, dear Corbu. It’s only two days since my last letter, yet I can’t help but write of each day’s goodbyes. In your absence, I am writing you into these last hours, so that you will not feel left out and I will not feel quite so lonely.

I broke the news to Mimi of my impending departure over a plate of roast beef. She had the fork to her lips when I told her, but kept eating, saying nothing until she had flushed it down with a mouthful of red wine.

‘Tell him you can’t,’ she said, finally. This is typical Mimi. Tell him you can’t. As if I could do that. I have no real money of my own. I depend on Papa for my allowance. Disobedience would mean losing everything. ‘Will you take care of me, then?’ I asked. She looked at me like a cat might a fish and said, ‘But you have Corbu to do that, darling.’

Don’t worry. I won’t be turning up at No. 24 to stake a claim. I take none of what Mimi says seriously – she and her melodrama. I sat there and stared at her smooth white face. She is still the whitest person I have ever seen. And believe me, such whiteness has its uses. A few years ago, Mimi and I were walking along the Thames, doing what we did best: helping the other to evade her assignments. As we strolled along the river, a fog dropped on top of our heads, obliterating everything around us. We couldn’t see our own hands, let alone the river or Big Ben. But then I saw Mimi, pale and glowing. Like a lighthouse, she helped me orient myself and led us to safety. Later we sat in the Fox and Hound with our friends joking that the coal may have been short that season, but its dust was certainly prolific.

What a cold winter that turned out to be. Do you remember? Everything froze. Britain – and the rest of Europe – turned to ice. By December we were desperate for signs of any coal – dust or otherwise. The snow fell with abandon into Berkeley Square until its edges and corners and everything else disappeared. I wrapped myself in woollen shawls and blankets and sat with my back to the stove, but it was no use. Mimi tried to help by arriving impromptu with bottles of brandy and long cigarettes. We drank until we couldn’t tell whether it was the cold or the drink that had made us so numb. That was when I took up smoking, just to get my breath warm again.

Meanwhile, the snow fell like fat feathers, causing traffic snarls and collisions. The airfields were closed and temperatures dropped to 30 Fahrenheit (don’t ask me what that is in centigrade, Corbu. When it comes to measurement, I have been fully colonised). Marcia and Werner kept the motorcar off the roads, for fear of an accident. When we did venture outside, we slid off the pavements and into banks of snow.

One evening, not long before that Christmas, Mimi suggested we go to her mother’s place in Paris. ‘Pourquoi pas?’ she said. Exams were over and I was shivering alone in my attic flat, smoking and drinking and doing little else. So, we went. And Marcia and Werner came, too.

Paris was cold, but infinitely prettier. We ate pain au chocolat for breakfast and wandered the streets until lunch. There was no rubble to step over or bombed out houses to mourn. You were lucky. It was as if the city had gone on holiday during the war, only returning when it was over. The flat was in a typical old Haussmann-style block with a cage lift and wrought iron balconies. Do you remember it? You haven’t been there for a while, have you? It is grand and elegant with enormous windows. It was also empty when we first arrived.

‘Maman was a brave woman,’ said Mimi. ‘She was a member of the resistance, you know. Not one of those salaud traitors.’ When she said ‘salaud’, she raised her voice, glaring accusingly at the walls. ‘Ils étaient partout, ces salauds.’ She shouted again.

I put a hand on her shoulder and told her I was sorry. Her eyes, which had been steely and angry, clouded over like two opals. ‘This is my flat now,’ she said. ‘Welcome.’

I looked into those same eyes today, and saw my reflection. They are as clear and cold now as they were in the winter of ’46, but that’s the irony, isn’t it? Because Mimi isn’t cold. As I sat there, watching her smoke one of those long cigarettes, I marvelled at the struggle playing itself out on top of her head. It was hat against hair, Corbu. Her red ringlets were springing in all directions like frightened rabbits, so that her hat quivered like a jelly. You see, that’s the real indicator of her character, that irrepressible mass of hair.

‘Of course I’ll take care of you,’ she cried. ‘I’ll take you to Paris. You can hide at my flat. Claim immunity from your despotic father. You can spend some time with Basquin. He told me he’d like to paint you.’

Do you know Jean Basquin, Corbu? I met him that same winter. Mimi took me to his place one afternoon, shortly after Christmas.

Arriving at the door of a ramshackle looking building, I was not surprised to find a similarly dishevelled man in its entrance. Taking in his brambly hair, wrongly-buttoned shirt and frayed trousers, I was put in mind of the crooked man in his crooked house, and peered inside looking for a crooked dog. But Basquin was on his own.

His breath was bad, but his manners were very courteous. The house was cold and shambolic inside. He showed us to a greasy settee and we sat in it, Mimi dropping into it like an anchor, me perching on its edge.

‘I would offer you tea,’ he said, ‘but the water in my pips is frozen. For sure, they will burst.’ He turned away, his face looking momentarily pained, saying to no one in particular, ‘Ah, the pips. The pips.’ With that, he left the room. I was freezing. There was no heating or fire to speak of – everything had ceased to function since the war. How Basquin lived like that, I could not imagine. He was wearing an overcoat and muffler indoors, but his fingers were still purple.

Basquin returned bearing two saucers with little beige slabs on them.

I put up my hand to refuse, when Mimi pinched my leg. I stared at the saucer on my lap and the frozen square at the centre of it that had been, in a warmer life, cake.

‘Mais vous êtes gentils, Basquin,’ said Mimi, biting into her slice and chewing it with a grin. ‘Merci.’

I followed Mimi’s example, smiling and sinking my teeth into my own slab, but no amount of pressure would break it. Worse than that, my bottom lip stuck to the bottom of the icy block. I grated at the square with my teeth, letting the little filings fall and melt on my tongue. Basquin was not impressed by my efforts and cast me such a look of hurt when he took my plate that I immediately tried to take it back.

‘Basquin wants to paint me, Mimi? Are you sure? Even after I was so rude last time?’ Mimi looked at me blankly. ‘The cake. Remember? I couldn’t eat it.’

Mimi laughed. ‘Oh, dear Minnette. What are you talking about? Of course he doesn’t care about things like that. He thought you were charming. Timeless. That’s what he said. “She is timeless.’’’

So, I am timeless. Just as well, Corbu, as I have a habit of being late to most things. And speaking of being late, I must dash. I’m meeting Mimi this evening for drinks. At the Fox and Hound, of course.

How I wish you were here, my love.

Ton oiseau

Minnette

1 June 1949

London

My dear Corbu, you should have seen me last night. I was stunning. I wore my red silk sari and two roses in my hair. When I walked through the Covent Garden piazza, everyone turned to look. A young man smiled at me, another bowed. I felt like a queen.

It was just like that time after the war, when Mimi and I went to the reopening of the Royal Opera House. Everyone stared then, too. Someone even presented me to the King and Queen! I remember how Her Majesty smiled at me, admiring my silks. She kept asking me about the colour and the drape and how one managed to keep it secure. Since then, my saris have become a privilege pass to all the parties at the Royal Opera House – all the parties in Covent Garden, in fact.

Last night, I was beckoned to and passed around like a tray of champagne. Mimi attracted a good deal of attention with her auburn curls. Marcia and Werner were there, too. Each time I reached for a glass of champagne, there was Marcia, wearing an expression of such horror, you’d think I’d been thrusting my hand into the jaws of hell. This is some new thing with my sister. Where has she gone, Corbu? In India, she was a virtual Bohemian. And in our younger days, we got into all sorts of trouble. I remember us nearly causing a riot in Kandy once. We had been part of a pageant telling the story of how Buddhism came to Ceylon. Of course, I was Sangamitta, bearing the branch of the sacred Bo Tree. And during a break, I leaned over and took a puff of Marcia’s cigarette. There was an uproar, and we had to be whisked away to safety. Marcia didn’t even drop her cigarette. She puffed it through the corner of her mouth while leading me out of the throng of angry Buddhists. Now, my sister – the same woman who thought nothing of aiding and abetting scandal – thinks I’m an alcoholic. Just because I enjoy a glass or two of whiskey. She doesn’t know that I’ve often shared the same with her dear husband. ‘You vill not tell Mahcia,’ he says, whenever we are out and she has disappeared to the toilet. He’s very crafty, my brother-in-law – always lighting up a cigar afterward to mask the odour.

Marcia’s caustic glares aside, the night was a success. I met a couple who enthused flatteringly about my architectural opinions. There was Tambimuttu, the wonderful Tamil poet, along with a number of other artists and photographers who were regulars at the Fox and Hound. And – best for last, Corbu – Ram Gopal! He looked splendid in a silk turban and shawl.

‘Darling,’ he said, embracing me, ‘I haven’t seen you for years, but you still look marvellous – marvellous.’ You would love Ram, Corbu. He’s a choreographic wizard. He’s taken the dances of the Orient and translated them for a Western audience. His performances are spectacular. The last time he was in London, I had to lend him my flat. It was autumn 1947, just a few weeks before Bridgwater. Ram rang me up in a fit because his manager had let him down. ‘Minnette, darling,’ he said. ‘He’s a waste – an absolute waste. A horror!’ He rolled the r’s to emphasise the injustice then, to ensure my sympathies really were with him, added: ‘A beast!’ The troupe was coming to London in two days, he said, and had nowhere to stay.

I offered temporary lodgings at mine and Marcia’s. He accepted. Within two days, my Savile Row flat was transformed into a green room. Dancers pliéd in the sitting room and did the splits against my walls. There was make-up everywhere and amidst it all, Ram Gopal, gorgeous and shimmering like a sapphire on one of his many turbans. ‘Look,’ he said, spreading his arms wide as if to gather up his dancers, ‘they are like my children – so obedient.’

As soon as Ram saw Mimi, he called out, ‘Ah, the walking paradox rises amongst us.’ This is Ram’s nickname for Mimi: The Walking Paradox. ‘She is so pale,’ he said to me once, ‘yet there is a vigor to her… like a radiant corpse.’ We kept the corpse bit to ourselves.

Mimi, Ram and I spent the rest of the evening casting mischievous judgements on our fellow guests. Marcia was not amused, but she so rarely is these days.

So, Corbu, the night beckons, again. Tonight I stay in with a book, a cigarette and a small glass of whiskey – and no Marcia to tut-tut me for it.

Ton oiseau

Minnette

4 June 1949

London

I’m having tea from one of my finest china cups. This is not, in and of itself, worth writing about, but there is something about the colour of this tea that makes me think of Bridgwater.

The tea is not as bad as it was there, goodness, no. In fact, it’s rather good. I like my tea the Ceylon way – plenty of milk and sugar with a shot of the best brewed BOP leaves to be found: those grown as high as possible in the hills.

I remember thinking this at Bridgwater. I was taking a break between talks, wondering whether I would ever get a chance to speak to you. I’ll be honest, Corbu. I was desperate to speak with you. I wanted to impress you somehow. To make you notice me – the architecture student from the East with a passion for Modernism. I wanted you to train those rounded specs on me – to look at me, to see me.

You were preoccupied. A fissure had opened up between the young and old architects. They were attacking you, Gropius and the Athens Charter with its absolute separation of functions within a city. Who could deny the unique and radical needs of post-war urbanism? Who could still believe that a site was a blank slate upon which a plan and its architecture could be imposed?

I have always wondered at the arrogance of supposing a place has no existence without a building installed according to a man-made plan. Sigiriya in Ceylon is exactly the opposite. It started with an enormous rock into which King Kasyapa carved himself and his entourage. It is the rock that stands out. The fortress – for indeed, that is what it became – is barely visible, hinted at only in contours from afar. Its monumentality is drawn from its natural state. Closer inspection finds intricate claws and a staircase disappearing into the suggestion of a creature’s gaping jaws, but all of this is hidden until you’re close enough to touch it. The fortress was an island unto itself. Buddhist monks had once used it as an escape from this material world. Kasyapa came to it to escape certain death at the hands of his brother for killing their father. The fortress, was always there, inherent in the rock. Much as Michelangelo would find his sculptures buried in marble.

People were milling about, sipping cups of tea and nibbling on hard biscuits. I was stirring two spoonfuls of sugar into my tea, absorbed by the vortex of hessian liquid swilling about in my cup. I heard nothing but the ting of the spoon on bone china. Even that sounded so much like home that the air cooled around me and the mists blew in against my temples. If I looked out, I thought, I would see green hills and a lake below, and creepers of carnelian flowers. And Amma would be behind me, talking to Jaya, our housemaid, about the intricacies of making love cake. Papa would be sitting on the verandah next to them, offering his opinion on the ratio of cadju to semolina. I turned around.

I felt you behind me, Corbu. I turned around to smile at you, to say, finally. No – I had much more to say than that. Sigiriya – I was going to tell you about Sigiriya, Kasyapa, Michelangelo. About Marg – the magazine Otto, Marcia and I founded in Bombay. I was going to ask you about Poissy and La ville radieuse. And all the while, I would watch you watching me: my hair, my necklace, my sari. I was ready, holding all this on my tongue as I turned around.

There was no one there. The crowds had been winnowed to a scattered few, most engrossed in writing notes or brushing crumbs from their lapels. I turned back to my tea and drank. It was weak and cold. I considered the ratio of cadju to semolina alongside my imagined parents and Jaya, and somehow made light of my disappointment.

That’s my confession, Corbu.

I long for your news.

Write soon.

Ton oiseau

Minnette

POST OFFICE TELEGRAM

11.17 Paris 16IEME

June 9, 1949

DESARAM 15 SAVILE ROW W1

FELICITATIONS ON ARIBA STOP IN LONDON IN TWO DAYS STOP WE WILL EAT CAKELC

12 June 1949

London

You were here in this room, standing on this sloping floor, cursing it even as you smiled at me. Your shadow fills the room, throws its great darkness right over Berkeley Square. You were here. My bed is unmade. I am unmade. Cigarette ash makes a pyre at my feet.

I want to feel your heart again, know the sharp crease of it, feel it here, against my back.

I am leaving. This is the only command that governs me now and I must walk into the truth of it. With every step I shrink and duck. I can’t, Corbu, how can I? Each step takes me back to Bridgwater, back to that moth’s wing of a moment that swept fortune into my hungry mouth:

I have just finished a lunch of tough lamb. The lamb sits like a monk in my gut. The Bridgwater conference is over and we are invited to an evening concert to bring a formal end to the week. I forego dinner in favour of a nap, so that I will be fresh for the concert.

I take my seat next to a member of the MARS group. She is slim and pretty and one of my AA colleagues. It turns out it’s not her seat. She shifts down and in her place sits you. We don’t notice one another. I chat to the person to my right while you are engrossed in Miss MARS. At some point and without provocation, we both tilt our heads towards one another and smile. Someone introduces us then – Miss MARS, perhaps – and you say, ‘Enchanté.’ And then the concert begins: the lights dim, people reorient themselves towards the stage. I sit and listen, but I hear nothing and see nothing except your eyes, magnified within those unmistakeable frames, peering at me with the curiosity of someone who has made a rare discovery, and the only sound to fill my ears is the shhh-shhh of that one word: Enchanté.

We don’t speak again that night except to wish each other bonne nuit. It is that night that I inscribe your name in my diary three times, as if forging your signature in that intimate space will bring you closer to me. It is an incantation – a mantram – the repetition of which should draw you into my orbit, or me into yours. And it works, because the next morning you come to me at breakfast and do not leave my side for an hour at least. You ask me so many questions, replying each time, ‘Ah, vous êtes sages.’

I say something about Benjamin Holloway and Robert Adams and you look at me with confusion. ‘Vous-êtes architecte?’ you ask, and are genuinely surprised when I say, yes. You ask me why, and at that moment, I can find no sensible reply. It is immaterial anyway, for you are captivated by the two roses in my hair. You tell me how much you admire my bearing and that elegance is somehow intrinsic to me. What flattery, but I accept it, eating it up whole, encouraging you further still to strew compliment upon compliment and smile a devilish smile that lights up those round glasses and convinces me that I have swallowed the sun.

I returned to London after that – to Marcia and Werner and dear, mad Mimi and before I knew it, was back to work. The Royal Academy was launching its Great Indian Exhibition and I was asked to measure every exhibit piece for the catalogue. It was a stroke of luck, giving me unlimited access to the Royal Academy – and the perfect excuse to invite you to London. When you came, I brought you to the museum early in the morning, when no one else was around, and showed you intricate bronzes of Hindu deities and Moghul paintings. How you examined them, listening intently as I described each item, admiring the voluptuousness of the figures with an academic eye, never once suggesting that they might be admired in any other way. (Later you would tell me otherwise, but that was later, when there was no possibility of offense, only laughter and indulgence.)

So it began: our meetings eventually with few words exchanged, as if we knew that words would return later, when we had time to savour them. You came to my flat, ascending these treacherous stairs without complaint, speaking of the crampedness of English spaces. I countered with something about the opportunities they gave for privacy and you laughed. But once inside, there were no more words to tell, only glances and sighs and my hands in yours. When Mimi and I visited Paris, timed assiduously for when Yvonne was away, you joined me at Mimi’s flat. How we painted our days then, with the brilliant tones of muscle, bone and flesh. It did not matter that we could not see one another for more than a few days. It did not matter that those days were separated by months.

And now we are to be separated by an ocean, with months that will spin themselves into years. Banished to an alien land, purged of the reassurance of touch, what will we do?

Words, Corbu. Let us find consolation in them. Let our words make us whole.

How strange it will be to go back to Ceylon, that place that belonged to another as long as I have been alive. After centuries of European rule – by the Portuguese, the Dutch and finally the British – Ceylon owns itself again. It’s been just over a year. Not much time, really, to recover from the shock of seeing one’s reflection after so long, of finding oneself scored with age at the moment of birth.

This is where I am going, then. To a country I do not know any more. Indeed, a country that may no longer know itself. And in that country, exiled from my lover’s touch, I shall be an island of remembering. I will look out upon my garden, with its pergola dripping red flowers and remember London, Paris and you. How you bent low to take my hand. How beguiled you were by the fall of silk on my shoulders. The lines, you said, were Grecian.

Ton oiseau

Minnette

II

December 1950 – June 1951

Stars, millions of them, beating like hearts. She sees them pulsing over the rim of her arrack glass. The sky is an open book, she thinks, written in a language I don’t understand. She slides back into the planter’s chair, tries to get comfortable, and fails.

‘Baby Nona?’

She sighs, takes another sip from her glass. Jaya is standing behind her, looking at the almost empty tumbler. She will not offer her another one.

‘Minnette, Miss? Ivarada, Miss?’

Minnette considers the contents of her glass. There is only just enough liquid left to wet the tip of a fingernail. One last sip. She feels the impulse before she recognises it. One last taste before she abandons herself to the community of sleep. That community, she realises, is up there, brilliant with dreaming. Millions of stars waiting for her.

She hands the unfinished glass to Jaya who tries, but fails, to conceal her disapproval. Even if I gave it back to her full, she would not approve. Young ladies drink sweet wine, not spirits. She smiles. Am I still young?

‘Baby Nona?’

Minnette shakes her head. ‘Hari, hari. Thank you.’ She waves Jaya away. Baby Nona. Even at thirty-two, Minnette knows she will only ever be the youngest, and so a child to Jaya.

Upstairs, in her room, Minnette collects her drawings. The Ariyapala Lodge is her first project. If not for her father, she might still be searching for work but fortunately, Ceylon – the new Ceylon – appears amenable to the ambitions of a woman architect freshly returned from England. It helps that the Ariyapalas are old family friends. Minnette’s drawings are neat, precise. The Ariyapalas were impressed. The house is sited on a hill, overlooking Kandy Lake. Minnette has sketched the elevation of the building, considered its aspect. Her calculations are meticulous. The house will be Modern and yet intrinsically vernacular. Materials will be local, as will the decorative work. Exterior spaces, like the balcony, will be as important as the interior. The Ariyapalas agreed to the plans without fuss. But as the months go by, first one objection, then another, is raised.

The project was commissioned more than a year ago. The honeymoon period, in which Minnette’s ideas were greeted with pleasant surprise and excited applause, has given way to suspicion, resentment, and occasional distress. ‘Hanh,’ says Mrs Ariyapala, ‘but why not paint the walls? Otherwise, it will look like an abandoned building, no?’ This to Minnette’s insistence that the interior walls remain unfinished. When Mrs Ariyapala realises that not only will the walls be unpainted, but they will also remain unrendered, she closes her mouth and does not open it again until she is alone with her husband, whom she then castigates for trusting an ‘upstart woman architect’.

All of Minnette’s energies are directed into the Ariyapala Lodge. She has set up her studio at Nell Cottage, hired local artisans to fire clay tiles, weave dumbara mats, carve and lacquer mouldings. The artisans are an extension of her studio, a community she, like her mother before her, hopes to nurture while engaging their considerable skill. She has forged friendships with weavers, learning techniques from them that she uses to create her own, exquisite saris. For Minnette, the Ariyapala Lodge is more than a house; it is the culmination of an architectural tradition that goes right back to Anuradhapura itself.

She examines her drawings as she arranges them into a pile. The foundations went down some months ago. Not easy, given her engineer had refused to work on them unless Ove Arup in London okayed the plans first. So, Minnette sent them to the famous structural engineer, whose first achievement had been the penguin enclosure at London Zoo. He approved them. The work continued. Still, Minnette has overheard the baas and his crew talking about that pissu ganni. They say she is crazy to site the house in an area vulnerable to earthslips. Minnette ignores them. Her task is to use every foot of land, sloped or otherwise, so that nothing is wasted. Anyway, it has been years since the last flood. She knows there is no risk.

She opens her notebook, makes two calculations based on measurements she took at the site earlier today. Accept this little card as a promise of more to come, he wrote. That was in June, just before she left London. A kiss for every one of your fingertips. Believe me when I say, this is not the end. And then, as a postscript: Chère amie, do not be offended. I ask that you do not send letters to No. 24, but to my office at No. 35. I know you will understand.

Minnette closes the notebook. She understood. She wrote back almost immediately: Corbu, please forgive me. I don’t know how it happened. Heartbreak, no doubt – a momentary madness. It wasn’t intentional. I would never do anything to hurt Yvonne.

In the quiet of her room, Minnette is suddenly, overwhelmingly, filled with need. Why doesn’t he write? She has been waiting for months and she is tired of it. Moths circle her lamp, immolate themselves. She decides to forget Le Corbusier, to ignore his letter when it comes. Then she sits down at her desk, moves her drawings aside, and begins writing.

Joyeux noël, Corbu. I have not heard from you in so – She re-reads the words, crushes the sheet of paper, begins again. Joyeux noël, Corbu! You must be busy – She crushes this, too, lights a cigarette, starts again. Joyeux noël, Corbu. This should arrive well after you have digested your goose or duck or whichever fowl Maman Le Corbusier is roasting this year. I’m sorry I haven’t written for a while. Like you, I have been busy. The Ariyapala Lodge. Not without its challenges, Corbu. They are trapped in their parochialism. The Ariyapalas are short-sighted, lacking adventure. Sometimes I despair. I could really do with some of your advice, if not the certainty you bring to a room as soon as you enter it. The knowledge that I am what I am because of you.

Minnette stops, considers throwing the letter in the bin, stubs out her half-smoked cigarette, and lights another. Too late, she thinks. She inhales and exhales a long puff of smoke, fanning it towards the window. Jaya would not approve of this either. Smoking is for prostitutes. As is arrack-drinking. Minnette applies the nib of her pen to the vellum sheet.

But what of the knowledge of who I am? That seems only to exist somewhere else, when we are together. I don’t know if I can survive this separation, Corbu. So many months without a letter from you – without a word. All this waiting. It gnaws a hole in me. Minnette puts a hand to her stomach, is convinced she can feel it hollowing out. This is what comes of being forgotten. Have you, Corbu? Have you forgotten me? ‘No,’ Minnette says aloud, causing a moth to flinch before extinguishing itself in her lamp. No, you cannot. Not yet.

You wrote, all those months ago, not to give up on us, so I will not. I know you have a good reason for not writing – What am I saying? You are Le Corbusier. That in itself is a reason. Everyone wants something from you. So, in the spirit of Christmas, I am going to give you something, Corbu. Take as long as you need to write to me. This is my gift to you. Time.

Minnette signs off, folds the sheets, puts them in an envelope and seals it. She places the letter in the centre of her desk and stares at the address written in flowing blue cursive. No. 35, it says. Not 24. She can be sure of this.

——————

Two months later, a letter arrives at Nell Cottage. It is from him. Minnette turns it over and over, thumb over index finger. The script on the envelope is erratic, difficult to read. She commends the postman for deciphering the address, for ensuring that the letter arrived at its intended destination. I will not open it, she decides. She opens it.

There are few words on the page. She resists the urge to crumple the sheet, directing her gaze instead to the jittery lines of text. Mais non, my little one, it begins, Corbu has not forgotten you. This can never happen! Minnette shrugs. She is used to the hyperbole, tries to defend herself against it, and fails. You are too generous, oiseau, sending me a credit note to claim against the months I have been absent. But you are right, too. Corbu is in demand! She nods. Corbu is always in demand. He is a busy man, a genius. Minnette should know better than to expect more than what he chooses to give her. She glances at the rolls of drawings arranged on her desk. It is nothing, she thinks, to build one house. My efforts are miniscule next to his.

She reads on. I have been asked to take on a project of immense scale in India. She stands, begins pacing the room. It is the dream of all architects, to build a whole city. For me, it will be Chandigarh. Nowicki’s death, Mayer’s resignation – these are the forces of Providence which state that Chandigarh will belong to Corbu. Like you, I will be working in a spirit of optimism – the optimism that comes with independence. Corbu will change lives – perhaps even a whole civilization. You and I, petit oiseau, will see one another once again, it seems!

Minnette holds the letter to her chest, closes her eyes. For the rest of the day, she forgets about her drawings. She cancels her afternoon meeting with the Ariyapalas who would only be vetoing something else she has proposed. They cannot stop finding obstacles for Minnette to trip over. She decides that today, she will not be a spectacle for them.

——————

Days peel away into weeks and months. Minnette’s desk is piled with drawings, no longer neatly rolled or filed. She has been asked to design a new building for the Red Cross, and a day nursery extension, both of which she tackles with efficiency. Given a small budget, she opts for something simple for the Red Cross: a building with a large events hall, its roof raised above the adjacent walls. She insists on making a feature of the surrounding land, so that the building opens onto the garden, rather than sitting flatly in the middle. But ultimately, her design is rejected. Her plans for an extension to the day nursery also come to nothing. It seems few people are willing to pay for innovation. They see it as a risk, she sighs.

The Ariyapalas are not so different; they still oppose her choice of exposed stone and brickwork for the interiors. Mrs Ariyapala has continued her mute protest, darting glances of disapproval at her husband which he, in turn, translates into a diplomatic ‘no’. Minnette does not know how to resolve this impasse. I am weak, she thinks. What would Corbu think of me? She has written one desperate letter to him, saying this much, confessing her shame. The great man replied: Corbu can never be disappointed in his oiseau. Courage, mon enfant! Minnette wishes she could summon the courage of a child – that blind wilfulness that compels children to climb to the top of a tree without a thought for how they will return.

She sits on her bed, smoking. Today’s meeting with Mr Ariyapala went badly. When Minnette showed him her designs for the sitting room – floor-to-ceiling glass windows and doors – he shook his head. ‘We never wanted such a grand design,’ he said. He looked tired, like a man defeated by age or marriage. His head was bent, as if to study Minnette’s drawings which were spread out on the table before him, but she could see that his eyes were closed. So stubborn, she thought. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘perhaps we can talk about this again in the new year.’ ‘Hanh,’ he said, opening his eyes, but not looking up. She gathered her drawings and left.

Minnette flicks ash into her empty glass. She has drunk half a thumb-length of arrack and is enjoying the numbness spinning a web at the back of her head. She stares out into the night sky and a million stars stare back. She pulls a small envelope from her sari blouse – a letter from Mimi – and opens it.

Inside: an invitation to join her in Paris for Christmas.

——————

I can breathe again. Minnette sips a glass of wine, shares a smile with a dark-browed Italian sitting two tables from her own. She is in Rome, her final stop. Before it, there was Venice, London, Paris. The heat of the evening reminds her of home. It has been more than six months since she fled Kandy for Europe, and now she must return. So many returns, she thinks. So many exiles. She observes the many couples, heads bent low over round tables, fingertips resting on cutlery. One man looks casually over the shoulder of his wife or girlfriend, and gazes at Minnette with deliberate and open intention. Minnette smiles, looks away. Why do I always do that? She looks at the man again, and this time he is the first to falter. She smiles to herself. Rome is grand and glorious and full of men with easy smiles. The ‘eternal city’.

Minnette remembers she has not eaten and orders some bread and olives. She closes her eyes, sees Corbu’s face, that amused expression he wears whenever he is about to take her to bed. Paris, she sighs. He was not expecting me. They had not had much time. She saw him, and her thoughts had come undone like a row of stitches. Yvonne was away. The flat was empty – No. 24! How could we have? – the flat was empty. He told me about India, he called me his ‘Inde’. She shakes her head, cringes at her weakness. There was no time to speak. The snow fell silently outside the window, his easel blocking out the remaining daylight. They were standing, side by side in the front room, watching the snowflakes flatten and burst against the windowpane like moths on the windshield of a moving car. What are words when flesh finds proximity after so many months apart. Words are unbearable then. His palm against her back. His mouth against her ear. How are you? Pas mal. Et vous? No. We used few words and so knew not – nor cared not – what the other had been doing between before and then.

Christmas arrived and to Minnette, drunk from being with him, the whole city was briefly enchanted: duck and pheasant hanging upside-down in the market; the rue Mouffetard with its exquisite pastries. Mimi and Minnette bought a different pastry from each boulangerie they passed. The only sour moment – which sullied the rest of the day – came when Mimi leaned over a mille-feuille to tell Minnette that she had heard from W.E.B. DuBois, Picasso and Paul Éluard that Le Corbusier had refused to sign the Peace Manifesto.

‘But Corbu would never ally himself with the fascists,’ argued Minnette, who had years earlier gone to Poland to address the World Conference of Intellectuals for Peace. At first, she went there on a lark, reveling in the wonder and fluster caused by her saris, but she returned a committed activist.

‘Picasso and Éluard are furious,’ said Mimi, sending a gust of pastry flakes into the winter air. And she was right, because Éluard dropped by Mimi’s later that evening for a drink, and he was fuming.

‘Le Corbusier, that fascist. Thinks himself a genius but he’s too self-important to put his name on a document that the world’s greatest artists and intellectuals have signed. Our plea to the world for peace – our plea for disarmament. He thinks himself better than all of us. Genius? He is a fascist! A sympathiser. A traitor.’

Éluard spat burgundy all over Mimi’s white carpet. His anger was not only palpable, but contagious. Why, thought Minnette as she watched Éluard’s trembling cheeks, why did Corbu refuse? Does he really think that we should be building stockades of more and more arms? The Americans in Korea – ‘Perhaps,’ said Minnette, ‘perhaps Corbu believes, like the Americans, that world peace is a Communist plot.’

Minnette shrinks now from the betrayal. At the time, Éluard had nodded and Minnette had felt vindicated in criticising Corbu. Now, sitting by herself at the edge of a Roman piazza, she is not so sure. It is enough to think such things – Minnette notices that her wine is finished; the bread and olives she ordered earlier remain untouched – to speak them aloud is inexcusable.

After Paris, Minnette went to London for the Festival of Britain, and watched the King open the new Royal Festival Hall. Models of tankers were moored in the Thames, while the V&A exhibited ‘the only surviving model’ of the Great Exhibition of 1851. The Festival Hall itself impressed her. A modern building for a modern age of entertainment, she had thought. She enjoyed the excellent acoustics in the auditorium itself, although the mass of the outer building troubled her, sitting like a hen on the ground.

Leaving London meant leaving her sister Marcia and brother-in-law Werner. Saying goodbye to Mimi was harder, but Minnette’s friend crossed her heart and told her she would be sure to make it to Ceylon for a visit.

Minnette tries an olive. It is the first solid food she has eaten since breakfast. Her head is heavy with wine. She knows that if she stands up now, she will not manage the walk to her pensione with dignity. She orders more food, a carafe of water and no wine. She will remain here until the numbness at the back of her head thins. She starts on the bread. Those winter months with Mimi were a godsend. If not for Paris, I would have been crushed by those Ariyapalas. It is true. Minnette has received numerous telegrams from her clients, requesting her early return so that work on their house can continue under her direction.

She recalls the Ariyapalas’ latest fearful demand – that she provide them some guarantee that their house would not ‘succumb to an earthslip’. She shrugs at the thought, then imagines the relief she might feel at watching the house and everyone in it swept away by the rain.

The man with his wife/girlfriend is looking at Minnette again, open intent now replaced by hope. She sighs. After London, it was Venice – the Renaissance city, gilded, lustrous. An exercise in proportion. A marriage of water and stone. Never mind that the city sinks, the romance of it is too great to ignore. Islands of arches and campanelli, Palladio’s Basilica, the Piazza San Marco – all of it fainting frame by frame into the Adriatic. Even Rome, for all its claims to immortality, will lie in dust one day, she thinks. Ultimately all our work will find its match in the elements. Stone or concrete, brick or glass.

She stares at her empty wine glass, remembers why she hasn’t ordered any, then orders another. There has been no letter since Paris. When she arrived in Venice, she found herself drawn along the bridges and piazzas of the city, strolling beside handsome young men – all of whom claimed they had fallen in love with her. Mimi’s painter friend, Francesco, was back in Venice and offered to take Minnette on a tour of the city’s waterways last week. Sitting in a gondola with him, she felt the pull of the water beneath her like temptation. It would not be difficult to believe everything any one of these young men says to me if only for a few days, she thinks. His silence makes the option all the more attractive, yet every time she imagines herself reaching out, it is to Corbu and no one else.

Minnette feels that urge again, that churning, knotting need that seizes her when she is not with him. She has some wine and takes up her pen. In the absence of your words, I allow myself to be charmed by others, she writes. She describes her gondola ride with Francesco with enthusiasm. Francesco is especially loquacious and beautiful in a godlike way, she adds. That is to say, beyond reach, as all divinity ultimately is. But to sit in a gondola and listen to him speak passionately of Venice’s bridges, its rising waters and softening bones, is like drinking a smooth merlot. Which is to say, he is rather delicious in his own way