7,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

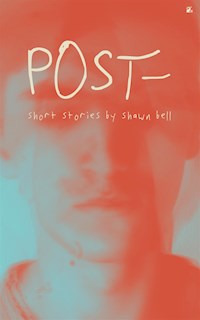

- Herausgeber: Antelope Hill Publishing LLC

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A fatigued traveler discovers a girl with a mysterious power in a city that simultaneously becomes the center of a global hoax setting a new political paradigm. A young man wanders into and out of an incredible inheritance in a scenario set up to contemplate the spiritual condition of a race in its twilight. Ordinary men in different contexts lend their eyes for a glimpse into the complexity and causes of social sundering in America.

The above briefly describes a few of the stories, parables, and allegories that fill this book. These stories, at once imaginative and down to earth, contain settings ranging from alternate futures and magical time travel to the real-life backwoods of America and a cast of characters including Baby Boomers who should have politically awoken but never will, working-class dissidents struggling in an atomized society, and the weak fathers and feminist mothers who failed to raise them. Each story is written not only with a skilled pen, but also a deeply perceptive understanding of the complexities of human relationships and personalities and the profoundly rooted causes of modern Western society's terminal decay. Touching upon themes including the temptation of fatalism, the futility of conservatism, the victimization of individuals by forces outside their control, the failure of authority figures, the pitfalls of human interpersonal struggles, and forever lost romances, this anthology with undoubtedly capture the attention of political dissidents and scholars of the human condition alike.

Relevant creative writing is more important to preserve now than ever and this unique work is an excellent example. Sure to be an instant classic, Antelope Hill is proud to present author Shawn Bell's debut work

Post-.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Post-

P o s t -

short stories by

S H A W N B E L L

J A C K A L O P E H I L L

An imprint of Antelope Hill Publishing

Copyright © 2022 Shawn Bell.

Second printing 2022.

Cover art by Swifty.

Edited and formatted by Taylor Young.

Antelope Hill Publishing

www.antelopehillpublishing.com

Paperback ISBN-13:978-1-956887-10-5

EPUB ISBN-13: 978-1-956887-11-2

- Contents -

Advent

Aspirational Negritude

The Blue Mountain Trust

The Grand Tableau

The Last Rhodesian (Or, Thumos Calling)

Lies and Traps

Of Mothers and Witches

Poverty and Plenty

Rescuing Nadezhda

When the Normies Began to Hate

- Advent -

The second he’d been awakened by the cessation of the somnolent jostling, he’d known that his miscalculation had been a grave one. Martial footsteps trod on gravel up and down the road of iron that had borne him there. There would be serious consequences were they to capture him. The men’s voices spoke in an impenetrable dialect which he identified as being of a southeasterly nature. This too was cause for concern, for the southeasterly corner of his land (or God forbid, the westernmost region of the neighboring one) was a poor region, inhospitable to his particular trade. Yes, the miscalculation had been a grave one indeed.

Such considerations are luxuries, however, when one finds oneself on the cusp of a beating at the hands of mercenary goons, and the Sojourner snapped immediately into a state of full awareness. Though things had never before gone as sideways as this, he was by no means unaccustomed to finding himself in strange freight yards with hostile authorities closing in. The thing was to act, a truth applicable in domains far beyond train-hopping. There are no perfect opportunities, and even the worst-timed dash toward freedom provides a greater likelihood of success than freezing in place and waiting to be discovered. The Sojourner was never paralyzed. He assessed the gravity of his situation, took a breath to distance himself from the dismal results of that assessment, and proceeded to action.

Dogs barked, men yelled at him to stop. There was a pursuit—indeed, a much more dedicated one than the usual lax standard of a night-shift railyard crew—but a combination of desperation and luck had seen the Sojourner through. Thus it was that he disappeared into that sleepy, provincial town where he was to meet his destiny.

He found an all-night joint catering chiefly to truckers and vagrants. Only once he’d warmed his hands on a steaming mug of coffee with a shot of something foul in it did he begin to take a long view. The name of the city was a familiar one, located on the correct side of the border, thank God. A backwater though, poor indeed, with very limited panhandling prospects, which boded ill for his chances of obtaining a costly berth on the long train headed back to the capital, which is where he’d hoped to end up in the first place, having been all but sure that the freighter would make a stop at the by now familiar junction on the capital’s southern fringe.

“Maybe you just slept through the stop,” piped up a hopeful voice within his mind, but he squelched that thought with an irritated shake of his head. No time for such foolish hopes as that. He knew perfectly well after all these years that the instant the train came to a stop, he’d snap immediately into a state of horrid and ineluctable wakefulness.

By the time the next seventy-two hours had passed, he would be feeling the precious lucidity he’d only just regained beginning to slip away from him. Once he’d entered the madness, events would begin to unfold in ways he had very little control over. That was when bad things happened. Very little time remained for him to avert disaster. Still, the Sojourner remained at the counter, lingering over a cup of greasy soup and indulging in a bit of reverie, thinking back on the prosperity of years past, and his decline to abjection.

Once upon a time, he’d been quite comfortably able to indulge in what was then a mere habit, riding in first-class sleepers between the prosperous cities of the Eveningland. Even as circumstances changed, and such luxurious travel was no longer financially or legally feasible for him, there had been years of relative comfort back in his impoverished native land, as there had remained enough of a leisure class of Eveninglanders with sufficient resources to travel—tourists were the bread and butter of his particular line of work. Over the years of the slow decline, however, his once-glamorous lifestyle, financed by elaborate cons and schemes, had come more and more to resemble panhandling, as the decline of external economic circumstances had been accompanied by a steady upgrading of his habit into a compulsion, and eventually to an absolute necessity. Still, as long as there had been tourists, he had been able to sustain himself, and more or less avoid the madness which lurked around the seventy-second sleepless hour, a terrifying inevitability that he lived his life in desperate flight from.

He could pick out tourists with great accuracy without even understanding how he did it. Even when they weren’t doing obvious things like snapping pictures, looking at maps, or smiling on Monday afternoons, he could always distinguish them. Maybe it was that tourists and children were the only people on the street who really noticed their surroundings. Maybe it was the lack of urgency in their movement. Whatever the subtle cue, he could spot them masterfully.

After spotting them, there was still some work to filter out the weaker prospects. Morninglanders were to be discarded, even though they tended to be flush with hard currency. Shy and retiring, they would become flustered upon being approached. What he needed was engagement, and with the Morninglanders, this was all too often a non-starter. Luckily, their distinctive looks made it quite simple to filter them out. Rather more subtle was the art of distinguishing local tourists from the surrounding lands, all quite poor, from their racial kin in the heart of the Eveninglands, a distinction that could not be made with a simple scan of facial features. Here it was the dress that distinguished his neighbors from the foreigners, as well as a certain wariness about the eyes; even those of his countrymen who were wealthy enough for the luxury of travel would have known deprivation and insecurity, for which reason they were much more averse to handing over their pockets’ contents than were the decadents of the West. Once he’d picked out his target (or targets: couples were particularly easy pickings, as the men were desperate to avoid to be seen as cheap or heartless by the women), the approach would commence.

It was mere mentalism from there—a simple art to explain, but a daunting one to practice masterfully. He’d throw out a few countries, waiting for a little flicker in his target’s face to tell him that he’d guessed correctly. And when the target would inevitably ask him, with no little surprise, how on Earth he’d known, he’d always come out with the same line—one Belgian (or whatever country) always recognizes another, my brother! From there he’d launch into a spiel about an uncle who’d built a business there, who’d always spoken about the kindness of the country’s people, mixing in various facts he’d learned about the chief landmarks of the capital city, as well as little phrases of the language so as to make it seem more plausible that he had in fact once lived there (at his peak, he had had such facts on mental file for something like thirty countries, though he had lost some of the information as the economic decline had gradually strangled the consumption spending of the less prosperous of the thirty). He’d tell how he’d traveled there once himself to work construction one summer, planning at the time to stay forever until the factory accident which had left his father crippled and in need of constant assistance.

The mention of his father’s ailment (here there was a little room for improvisation, and the Sojourner rather enjoyed coming up with new, gruesome misfortunes to give him) provided a perfect transition into a tale of woe. All his family dead and buried but for his poor sickly papa and him. The problems in the country that had him sleeping on the street. The job offer he had, alas, in another city, and he without the money to buy a train ticket there. He always got a lusty little kick out of the change in expression that came over his targets’ faces when they realized that what they’d taken for a friendly interaction had ended up being a panhandling shtick. They were trapped by their own politeness. Eveninglanders found it extremely difficult to rudely break off an interaction and walk away from a friendly conversant, and the Sojourner was a master of leveraging this politeness for his own ends. The longer he extended the interaction, the more uncomfortable they would become. Desperate to escape, they would become willing to let him name his price to set them free. He could make his pitch in five languages. Such a master was he that, in the salad days of tourism, he had been able to live almost lavishly, always able to afford the night’s train ticket, never coming close to the madness of insomnia.

Only after the movement restrictions were instituted, and the long-dwindling tourism had been ceased overnight, did the madness become a constant threat, something he was constantly wavering on the edges of. He resorted to criminality at times, but with a week locked up being tantamount to a sentence of death by sleep deprivation, the risk outweighed the reward. Freight-hopping bore much the same risk, and he resorted to it only when the hallucinations were on the verge of taking over completely. Even on the nights when he came up short on cash, he’d walk down to the Glavni Vokzal nonetheless, to watch the gleaming train chug away from the station and dream of being on it, rocked to sleep beneath the stiff, sterile-smelling railway sheets, insensible to anything around him. And then he’d wile away the unprofitable nighttime hours, sometimes with the rest of the human refuse that lurks at train stations the world over, but mostly on his own, zombie-trudging the tree-topped promenades as the cheerful nighttime revelers swirled around him more and more thinly, peeling off and returning to their respective abodes to partake in the repose which he envied them so keenly.

In much the same manner, though with much less hope, did the Sojourner wander the streets of the sleepy, provincial city in the days after his arrival. Things were worse than he’d thought. The freight yard, and indeed the town itself, swarmed with military personnel, and when he’d inquired to some locals as to what the story behind the occupation was, they’d just looked at him with narrowed eyes, before lowering their heads and scurrying away. By the third day, he was no longer in any shape to ask anyone anything. In any case, the freight yard was completely inaccessible. It had been through the sheerest of dumb luck that he’d managed to avoid apprehension upon his arrival, and with every passing hour more personnel arrived, their encampments, including at the freight yard, growing ever more permanent and well equipped. His attempts at begging had proven universally unsuccessful. His vision began to darken and fragment. Before too long he’d make a mistake and wind up incarcerated, slowly expiring from exhaustion. His thoughts became scattered, and a horrible dread rose up within him. It was in this state that the Sojourner wandered down the sheer steps to the little municipal garden located halfway down the cliffs than overhung the stormy sea that battered the little city from the south.

The tinkling of a familiar melody cut through the rush of the waves upon the rocks, and through the fog of his exhaustion, and the Sojourner recognized a strain of an old song, well-known to all his people. As he approached the gazebo at center of the park, where the municipal authorities had positioned a ramshackle old piano for public use, the song became clearer and clearer, and a heaviness began to overtake first his limbs and then his eyelids. With an unnatural, charmed suddenness, sleep came upon him, and he was scarcely able to make it to one of the park’s worn wooden benches before his consciousness left his body.

For an unknown period, he slept. It couldn’t have been long, for the girl, though she devotedly visited the piano in the garden every afternoon after school, never stayed longer than an hour or so. Still, even that morsel of respite had been enough to clear away some of the gathering clouds of madness and restore him to precious lucidity. He watched in wonder as she rose from the bench—he’d snapped with the usual suddenness back to consciousness as soon as she’d lifted her fingers from the keys—and glided mysteriously away, a slim, mousy girl in an old coat, no more than fifteen or sixteen years old. It was the first moment of sleep he’d been able to snatch outside of a traveling train since his unusual malady had reached its acute state almost a decade before.

Not having all that much to do beyond fruitlessly attempting to lay hands to money, and waiting for the next brief period where the girl’s afternoon ministrations would allow him a precious increment of slumber, the Sojourner had taken to following her around, learning her ways and tendencies, seeking to pin down something special about her that might explain the fact that she had managed to succeed where no drug, no therapist, no recording of soothing oceans sounds had been able to. What he’d discovered about her, however, was depressingly average.

Her home was not all that dysfunctional, relatively speaking, though her family had been subject to the same forces of degeneration which were in evidence the world over. It was a family of women, composed of the wisp of a girl; her cashier mother, a tart in her mid-thirties for whom the drama of the courtship ritual had become an end in itself; and her grandmother, a desiccated old woman of traditional morals whose congress with the outside world consisted of chain-smoking cigarettes in the plastic chair she’d set up by the muddy sidewalk in front of the house, and daily presence at the Divine Liturgy. The grandmother owned the house they lived in, and between the lack of rent payments and the little vegetable garden the dogged old woman kept, they were able to get by on the meager wage the mother earned scanning groceries at the little shop on the corner. Though raised voices were periodically audible from the street outside the house, the Sojourner noted that the girl’s voice was never one of them. On those occasions where only one of the two voices was heard, the Sojourner assumed that the girl was playing the role of mute audience, her face as impassive as ever, and her inertia provoking ever higher dudgeon.

It was clear that the mother’s and grandmother’s respective irritations with the girl stemmed from their shared inability to dominate her, or indeed to influence her very much at all. Both older women were in complete agreement that the sullen teenager was in dire need of an attitude adjustment. As to the optimal nature of said adjustment, however, it was clear that the two couldn’t have been at any greater odds. The grandmother wished for the girl to follow in her footsteps, living a simulacrum of the sort of traditional lifestyle based in faith, family, and rigidly-defined social practices of a bygone era—a simulacrum, that is, because this sort of lifestyle was no longer achievable beyond a superficial semblance, as anyone with more meaningful congress with the outside world than the deluded old woman would have immediately seen. The mother, meanwhile, had never moved beyond the coquetry and cattiness which had granted her such thoroughgoing social power through her sexual value as an adolescent—though she had squandered that power completely by producing offspring with a sneering punk who had of course abandoned her, rather than leveraging it into the sort of reasonable match which would have provided her with security, and indeed even opulence, so arresting had her beauty once been. Having once been a queen bee of her adolescent social hierarchy (and lacking the insight to fully appreciate the causal relationship between her sexually prolific, emotionally stunted youth and her current situation), it was only natural for the mother to wish the same for her daughter, and to become increasingly frustrated by the girl’s morosity and refusal to engage in the sorts of activities the mother considered to be worthwhile.

The girl, meanwhile, seemed to want more than anything else simply to be left alone.

Indeed, the only thing that stuck out to the Sojourner as being in any way unusual about the girl was the inordinate amount of time she spent by herself. She was always among the first pupils to exit the secondary school where he waited every afternoon, following at a distance as she made her way down to the gazebo in the little garden, his heart always seized with terror that this would be the afternoon she was otherwise engaged, and he would be denied the salving relief of a few moments’ sleep. She walked down to the garden alone, played him to sleep, and walked straight home where, although she was not strictly speaking alone, she may as well have been for all she interacted with her family members. When he’d peeked in her window, he’d sometimes seen her occupied with homework, but more often than not, she’d simply been lying in bed, atop the covers, awake but inert, staring opaquely up at the ceiling of her little closet of a room.

The music she played was bog standard. When he’d recorded one afternoon’s performance to see whether the music’s miraculous effect could be replicated away from a live setting (it couldn’t), he’d listened through to the whole recording to see whether any musical genius shone through and, to be perfectly blunt, it hadn’t. The girl played a medley of simplified classical tunes of the sort one would learn from an intermediate-level instructional piano book, along with some sentimental, contemporary pop songs and the occasional older folk tune. She did so with an unassuming amateurishness, with halting tempo and frequent false starts and missteps. And yet, it seemed as if he was not the only one who was entranced.

Over the weeks, the Sojourner noticed a definite uptick in the attendance at the girl’s afternoon concerts. There were familiar faces among the devotees, though all made assiduously sure, out of some sort of strange shared intuition, to conceal the fact that they had come to the garden for any reason other than happenstance. Soon he began to spot them lurking in the shadows as he stalked the girl—they too were becoming obsessed, surveilling her every step. It seemed, however, as though the girl remained as yet unaware of her power, for she continued her routine as ever, affording to the Sojourner just enough sleep to keep his wits about him as he planned his next move.

Perhaps he could find some little job, stay on in the city indefinitely. After all, it had been the need to purchase a berth in a sleeper car every night which had made an itinerant of him. And while the depressed local economy certainly had little to offer him, his experience in certain illicit lines of business would no doubt serve him well here; vice sells particularly well in gloomy places with unpromising futures. He even allowed himself to imagine hiring the girl to play for three, four hours per day, maybe on a piano that he’d purchase for his own house and place next to a king-sized bed with downy covers. He’d positively revel in the fantasy, though he never took any sort of action. For reasons unknown to him (and the rest of the secret acolytes of the unspectacular girl with the dark hair and dark eyes), the whole situation felt like a fragile, unstable equilibrium that could not, under any circumstances, be disturbed.

As it turned out, they had been correct in this hunch. As is the inevitably the case whenever a fragile equilibrium is allowed to persist for a period of time, a disturbance cropped up and blew it all to pieces. That is, one afternoon, one of the devotees, a young man whose infatuation had overwhelmed his terror of approaching the object of his adoration, had accosted the girl and gushed to her about the effect her playing had had on him. As he’d babbled on, she had begun to scan her surroundings with palpable apprehension. The Sojourner could see that, in a sudden, she’d realized that they were all there to see her, and he knew that never again would she return to play the piano in the park.

*

The girl had not, in fact, realized that she had admirers. Or to put it more precisely, though she had for a moment realized it, she had long since trained herself not to allow such realizations to solidify into persistent awareness. This was because such awareness gave rise to questions, and questions had answers that, more often than not, hurt.

One such question, for instance, might be, “why on Earth did I stop playing piano, when doing so had once brought me such joy?” So important had the piano become to her that, for some months previously, the girl had planned her days around the visit to the little garden. The thought of it had borne her through the constant indignities and impositions of interacting with the world, and when she’d played she’d felt relief. And now she no longer played. Answering this question would necessarily involve painful confrontations with aspects of herself she wished to avoid, the girl deftly avoided it entirely by almost completely forgetting that she’d ever played the piano at all, though if someone had asked her point blank about it, she’d have answered in her faraway way, without making eye contact, that yes, she’d played piano a bit as a kid, truly believing herself that this had all taken place in the distant past.

So it was with the Diggers as well. For a time, the girl had been an accepted junior member of the informal club of eccentric local men and boys whose favorite pastime it was to explore, map, and maintain the elaborate network of catacombs which spider-webbed beneath the city. During that period, she had found joy among the Diggers. And now, without once asking herself why, or even admitting to herself that the tunnels had once played an important part in her life, she had ceased to have any contact with them, and become cold and inscrutable to Gnome, the classmate who had first gotten her involved in the tunnel community.

This approach had worked wonders for the girl in terms of the avoidance of emotional discomfort. She thought she had perfected her defenses. Thus, it was particularly disconcerting when, after that run-in with the wild-eyed, foul-smelling vagrant who’d tried to snatch her off the street, all her work had come undone, and a lifetime’s worth of questions had begun to arise unbidden.

It had been about a week after the conversation with that overawed young man had convinced her to walk away from the piano forever when the tramp had clasped her wrist in his leathery paw and begged her for deliverance, wrenching her arm in the direction of the municipal garden and forcing her to resist in the only way she knew how: passively. Through force of will, she anchored her slight frame to the ground and waited, unpanicked, for the other bystanders in the town square to free her. But though it had seemed to her at the time that even this physical attack had proven incapable of penetrating her impregnable defenses—none of her vital signs, which she kept constant mental tabs on, had appreciably increased beyond the level one would expect as a result of the physical exertion of her resistance—the ensuing days had proven otherwise. The bystanders had pulled her assailant away and carried him off to the authorities who had, in their turn, more than likely confined him to whatever space it was that they used for the warehousing of dangerous lunatics—but as they’d pulled him away, the glint of his yellow eyes had produced a sensation in her heart from which had ensued an outpouring.

Thus it was that the girl was confronted, among other things, by a number of nagging and unresolved questions regarding the meaning of her aforementioned time with the Diggers, and, seeing as these questions could not be made to dissipate by her usual methods, she had begrudgingly begun, for the first time, to sift through her memories of that time.

Her affiliation with the club had been the result of a group project in school. There is a certain type of kid who waits until all her class’s students have paired off voluntarily, leaving herself to be assigned one of the undesirables still remaining. To the girl, this approach had numerous advantages. Through her passivity, she avoided the perilous vulnerability of seeking someone out, an attempt which entailed a risk of rejection, as well as, even more perilously, a risk of acceptance. Furthermore, by consigning herself to a partnership with one of the social rejects who, let’s face it, are often such for legitimate reasons, the girl made it all the less likely that she’d end up endangering herself by forming a personal connection. Finally, seeing as the social rejects also tended to be academically marginal, both parties were generally perfectly content with a partnership which required no actual collaboration, as the girl would simply do the work herself. At first, the work she’d turned in had been exemplary, but upon finding that academic exceptionalism made her into an attractive partner, she’d scaled back her efforts so as to receive adequate but undistinguished marks.

Gnome, cursed by fate in several regards, had been a perennial reject from the very beginning, and as such, had been paired off with the girl on more than one occasion over the years. His receding jawline, stutter, and diminutive stature had been exacerbated by an ever-worsening skin condition as he entered adolescence, which was not helped by his lackadaisical approach to hygiene, as well as the fact that he could not keep from picking at the cysts until they bled. Socially, he had been cursed by a desperate craving for attention which expressed itself by a tendency to pester the less marginal kids, flooding them with attempts to impress, and degrading himself in the pursuit of some measure of acceptance, even if it were only as the target of everyone’s derision.

His academic abilities were negligible, though this at least seemed not to cause him much consternation; the previous times they’d been paired off together, Gnome had been perfectly content to bite his nails and look out the window as the girl did all the work. Thus, when the pairing had been repeated, she’d been relieved. The assignment being to produce an original ethnography of a local community of one’s choice, the girl could envision how the process would play out. She’d choose some safe topic, uncreative and deadly dull, and her defenses would remain intact. Thus it was that her stomach had dropped in trepidation when Gnome began, in a most uncharacteristic fashion, to excitedly chatter about a proposed topic which he was clearly firmly committed to: an ethnography of the local tunnel explorers, the Diggers, with whom he had become affiliated in recent months.

Twitching and sweating with the effort to get the words out, he told her all about the group of amateur enthusiasts, some of the most obsessive of whom had developed real expertise in the history of the local limestone industry which had produced the tunnels, being able to date the various shafts and contextualize them within local history by subtle indicators such as the dimensions or signs of the tools used for the excavation. Others had become more interested in the local flora and fauna, the rats and bats and tunnel-cats that had moved in as the labyrinth had been abandoned. There were rumors of criminal gangs having operated smuggling operations in the tunnels; of rebels and dissidents having used them as bases from which to launch their ambushes; of more or less permanent communities of down-and-outs; of ancient, hermetic religious orders; all of which rumors were hotly debated by the tunnel enthusiasts, as well as the old folks in the surrounding villages, who enjoyed scandal in all its forms. No doubt some of the rumors were true, while others were as fantastical as can be, but from an ethnographic perspective, of course, the facticity of such mythologies was not the issue, but rather the importance of the shared stories in creating a sense of community, of sub-culture, among the denizens of the catacombs.

The girl had to admit that it was a good idea—the sort of idea which, if well-executed, would be sure to attain them just the sort of outstanding marks she’d been trying to avoid. But the prospect of resisting Gnome, who was so invested in the idea that he had literally jumped out of his seat in his effort to explain, seemed like a grueling one. After his passionate pitch came to an abrupt and disorganized end, the girl had responded simply and flatly, “xorosho.”

She hadn’t fully realized that by giving in, she was agreeing to actually go down into the catacombs with him, and when she found herself standing, shivering, in a field of scrubby grass the following Saturday in gray, bitter November, she wished with all her heart she’d had the will to stand up to him, tell him his idea was stupid, and suggest a topic which could be researched from the warm recesses of the library. But when he’d pulled up on a bicycle rigged up with a sputtering benzene engine, disheveled, unshowered, but not more than ten minutes late, she’d had no more time for fantasies of a day spent alone in comforting tedium; after apologizing profusely for his lateness, Gnome had abruptly turned and walked off into the field.

“Well, come on,” he’d called out over his shoulder as he walked on.

After five or so minutes they came upon a great fissure in the ground, and as Gnome scrambled down he explained that this entrance had been used as a garbage dump by some heedless locals and had been impassable until just a few months ago, when he and a couple of his compatriots had cleared it out. He’d passed her a flashlight, and without further ado set off.

Down below, Gnome’s speech was as rapid-fire as ever, but somehow he seemed much more collected than he ever was on the surface. In his element, he spoke with an expert’s confidence about the miners’ graffiti, written in the elegant cursive of bygone days, but just as coarse in its content as the scrawlings in your average bathroom stall. Without pause, he gave a brief overview of the history of mining techniques and regulations, pointing out some scoring of the rock, describing which tools the scoring indicated had been used, and what that revealed about the period when their particular tunnel had been carved out. He shared the names of some of the more important sections of the catacombs as they walked through them, and decrypted the system of markings that the Diggers scratched into the walls to aid navigation. All of this was a simplified rehash of the things his more well-versed mentors had explained to him, but his confidence in telling it all was infectious. Though the girl had remained as outwardly silent and inscrutable as ever, she had been fascinated by the hidden world he had allowed her to access.

They squeezed through narrow passages on hands and knees, scattered swarms of rats with the beams of their flashlights, scaled heaps of debris, and splashed through the vile-smelling water which trickled through parts of the system. They went down and down, all of the girl’s navigational volition entrusted to her new friend, passing through various interconnected sub-systems, all with their own names and stories. Periodically, Gnome would announce which local landmark they were standing beneath—there were hundreds of kilometers of ad hoc labyrinth under their city, though some of it had been rendered inaccessible by collapses or flooding. There was no telling how quickly time was passing, but it seemed to the girl that they had been down there for hours when they spotted the movements of another flashlight around the corner.

“Glück auf!” Gnome shouted, butchering the foreign words’ pronunciation, though the girl was none the wiser, and, when the distinctive Digger’s greeting was called back in return, Gnome had recognized the voice that called it. They’d come around the corner to find a spectral man with deep set eyes and a doleful expression, scrubbing away at the wall to remove a particularly filthy bit of graffiti.

“Oh, hi sir! Didn’t expect to run into you here! Let me help you with that!” burbled Gnome, pushing the older man aside and taking over his lowly task. The man smiled wanly, a bit of irritation showing through, though he indulgently handed over his steel brush and stood aside. As he scrubbed, Gnome had stuttered through mutual introductions, referring to the older man as “The Mapmaker,” evidently an honorific of no little significance among the Diggers. He’d proceeded to explain to the Mapmaker his idea for the school project they had been assigned, his tone implying that permission was being requested. The older man had been silent for quite a long interval after Gnome had finished speaking, but finally he replied:

“Yes, well, I suppose that’s all right, provided you don’t reveal any of the secrets. I know you, Gnome. You wish to impress people. But it’s not worth giving away your place in the world. This place is special because it’s ours.”

His voice was reedy and hoarse, as doleful as his expression. He nodded briefly to the girl in acknowledgment of her presence before producing another steel brush from his bag and turning back to the wall. When she had picked up a third brush and begun to pitch in as well, neither of the two had looked up. In silent companionship, they scraped the wall clean, ate sandwiches, and performed a bit of maintenance on a support column the Diggers had built from scraps of stone to preempt the spreading of an ominous crack that had emerged in the roof of one of the most well-traveled branches. By the time they emerged once again into the superterranean world, the sun had begun to fade. In the sickly light, the Mapmaker had briefly explained to them, his eyes directed at his shoes, that some Diggers had planned an excavation for the next weekend, a relatively large-scale effort to safely clear away the caved in rock and soil that had blocked off what he had reason to believe to be one of the deepest and oldest sections of the labyrinthine network. He’d said they’d be welcome to come, shrugged, and shuffled off into the blustery evening.

Looking back on this saga, which she’d done her utmost to erase from her memory, the girl remembered, suddenly, that she’d walked home with a slight smile on her face that day, which had stayed in place until she’d caught a glimpse of her reflection and hastily wiped it away.

*

The next weekend, and indeed for several weeks following, the girl had taken part in weekly expeditions into various parts of the system of catacombs, always initiated with some specific and tangible purpose in mind. The Diggers collaborated with a remarkable lack of ego, all taking up shovels or brushes to pitch in where needed. They reinforced sections of ceiling identified by a retired engineer who, like the Mapmaker, had a particularly venerated status among the Diggers (though this status did not except him from performing the same hard, dirty labor as the rest of them); cleaned out trash from the various openings that the unappreciative savages on the surface decided, periodically, to use as dumping grounds; and sabotaged the sewage pipes that unscrupulous corner-cutting contractors would pipe directly from a house’s toilet into the catacombs. There was always something to do and, absurd and pointless though the task of preserving and exploring the maze of tunnels seemed to be, doing so conferred a sense of purpose which the girl appreciated very much.

Best of all was the manner in which they left her alone. Hare-lipped and walleyed, rotten-toothed and socially maladjusted, the Diggers were a forlorn bunch. They took the hint from the beginning that the girl preferred to be invisible, and they treated her as such. Even Gnome, though he chattered away with his usual lack of awareness when the two of them were in transit to or from a Dig, had taken the cue. All there was, was the task, and the bare minimum of togetherness necessary to accomplish it.

Things were going as well as they could conceivably be expected to go. Irate as both grandmother and mother had become when they’d learned where she’d been spending her days, the girl would not be deterred. Without articulating the thought or naming the feeling, she felt accepted, and indeed joyful, albeit in her peculiarly restrained and unemotive way.

The weekend before the ethnography was to be presented to the class, the Diggers had made tremendous progress in one of the excavations the Engineer had been planning for some months previously. It had taken weeks of preparatory work, installing numerous supports and clearing away man-sized boulders from the collapsed passage. Everything had had gone precisely as planned until the moment when the girl’s foot had broken through what they had previously taken to be solid ground, revealing a sheer drop traversed by a strikingly narrow and ancient bridge. It appeared to be a passage leading down to the storied fourth level, which had been much discussed by the unreliable tongues of the town’s elders but never yet accessed, and it had been all the elder statesmen could do to resist the reckless exploratory urges of the younger members.

“A groundbreaking discovery, to be sure,” the Mapmaker had agreed with them, peering at the girl who had inadvertently discovered it with discomfiting avidity, “but there are proper ways of going about things. We need to proceed with extreme caution. Without the proper equipment, as well as a good deal of careful testing and most likely restoration work, I cannot allow you in good conscience to cross that bridge.” There had been grumbling, but ultimately the Mapmaker’s authority had held sway, and the Diggers had agreed that there would be no harm in coming back next week with the proper gear for such an exploration, as well as having the new system fully explored by the most experienced members before allowing the younger, more reckless members to enter.