Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Arc Translations

- Sprache: Englisch

Vladimir Mayakovsky was one of the towering literary figures of pre- and post-revolutionary Russia, speaking as much to the working man as to other poets. His fascination with sound and form, linguistic metamorphosis and variation made him a sort of 'poet's poet', the doyen, if not the envy, of his contemporaries, (Pasternak among them). His poetry is strangely akin to modern rock poetry in its erotic thrust, bluesy complaints and cries of pain, not to mention its sardonic humour. It is often aggressive, mocking and yet tender, and can be fantastic or grotesque. That's What is a long love poem detailing the pain and suffering inflicted on the poet by his lover Maria and her final rejection of him. But as well as being an agonising parable of separation and betrayal, it is also a political work, highly critical of Lenin's reforms of Soviet Socialism. The publication of That's What is something of a landmark as this the first time that this seminal work has appeared in its entirety in translation. Included also are the 12 inspired photomontages that Rodchenko designed to interleave and illuminate the text, illustrations which inaugurate a world of new possibilities in combining verbal and visual forms of expression and which are reproduced in colour for the first time. "Arc have produced a handsome Russian-English edition of this personal epic of the early years of the Revolution, first published in the LEF journal (Left Front of the Arts) in 1923. George Hyde adds a lively note on 'Translating Mayakovsky's That's What'. His co-translator, Larisa Gureyeva, is the granddaughter of V.M. Molotov-Skryabin, co-signatory of the notorious pact with Germany of 1939. Hyde writes of the 'permissive' 1920s in the early Soviet Union. Following the recent splendid exhibition of Rodchenko and Popova at the Tate Modern, there are increasing signs of a growing interest in the early, tumultuous years of the Russian Revolution." The Spokesman Vladimir Mayakovsky was born in Georgia in 1893, but moved with his family to Moscow after his father's sudden death. By the time he was 20, he was a well-known literary figure, having toured Russia in the winter of 1913-14 with the Futurists (with whom he had identified). He made several trips abroad during the 1920s, including a long visit to America in 1925. A prolific writer, he still remains a popular poet among present-day Russian readers. He died in 1930 by his own hand, killing himself playing Russian roulette with a single bullet. Aleksander Rodchenko was a Russian artist, sculptor and photographer and one of the most versatile Constructivist and Productivist artists to emerge after the Russian Revolution. This book is also available as an ebook: buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 98

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRO ETO

ПРОЭТО

That’s What

Published by Arc Publications

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road

Todmorden OL14 6DA, UK

arcpublications.co.uk

The poem ‘Pro Eto’ by Vladimir Mayakovsky was first published inLEF,1923.

Translation copyright © Larisa Gureyeva

& George Hyde 2009

Design by Tony Ward

Printed by MPG Biddles Ltd

King’s Lynn, Norfolk, UK

978 1904614 31 9 (pbk)

978 1904614 71 5 (hbk)

978 1908376 38 1 (ebook)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Russian text ofPro Etois reproduced from the original version published inLEFin 1923.

The photomontages by Alexander Rodchenko, produced in collaboration with the poet and first published in monochrome, are here reproduced in their original colour version by kind permission of the Director of The State Museum of V. V. Mayakovsky, Moscow.

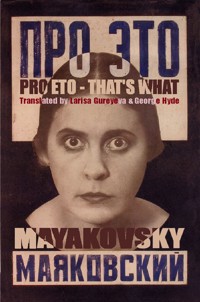

The cover design is an adaptation of the cover of the original edition of 1923, Rodchenko’s portrait of Lily Brik.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Director of The State Museum of V. V. Mayakovsky, Moscow.

The publishers acknowledge financial assistance from ACE Yorkshire

Arc Classics: New Translations of Great Poetry of the Past

Series Editor: Philip Wilson

Translations Editor: Jean Boase-Beier

Vladimir Mayakovsky

& Alexander Rodchenko

•

ПРО ЭТО

PRO

ETO

That’s What

•

Translated by

Larisa Gureyeva & George Hyde

Introduced by

John Wakeman

2009

CONTENTS

Introduction: Vladimir Mayakovsky and THAT’S WHAT

Translator’s Preface: Translating Mayakovsky’s THAT’S WHAT

•

ПРО ЧТО – ПРО ЭТО?

What’s This? – That’s What

I. БАЛЛАДА РЕДИНГСКОЙ ТЮРЬМЫ

I. The Ballad of Reading Gaol

II. НОЧЬ ПОД РОЖДЕСТВО.

II. Christmas Eve.

ПРОШЕНИЕ НА ИМЯ…

Application on Behalf of…

•

Notes

Biographical Notes

Locations of Alexander Rodchenko's colour photomontages:iiiiiiivvviviiviiiixxxi

Посвящается ей и мне.

Dedicated to her and to me.

Although Alexander Rodchenko produced the above illustration [untitled] as part of his series of photomontages forPro Eto – That’s What, it did not appear in the first published edition.

Vladimir Mayakovsky and THAT’S WHAT

The long love poem called hereThat’s Whatis entitled in RussianPro Eto, which literally means “About This”, with the strong suggestion that the author felt the need to defend himself against the criticism that had come his way for the irregular nature of his unconventional love-life. Typically, the Russian words carry echoes of the words for “poet” and “proletarian” as well as expressing a characteristic off-hand defiance which is a sort of protective colouring. Love, the class struggle, technological change and the creative process itself all fuse together in what George Hyde identified, in his translation of Mayakovsky’sHow Are Verses Made(1926),aas the “expanded metaphors” typical of this poet’s work. Indeed, Mayakovsky’s elaborate incremental metaphors and metonymies reflect, in this poem as in all his work, the creative fascination with sound and form and linguistic metamorphosis and variation that made him a sort of “poet’s poet”, the doyen, if not the envy, of other poets (Pasternak, for example) who by no means shared his revolutionary political convictions and commitments.

Mayakovsky’s empathy with the urban poor was born of experience. The son of a forest ranger, born in 1893 in Georgia, he was forced to move with his family to Moscow after his father’s sudden death. The world of rented rooms and poverty, intensified subsequently inThat’s Whatby communist Moscow’s painful attempts to catch up with modernity, is matched by the creativity of a brilliant artistic imagination engaging in its own way with the verbal and visual experiments of Futurism, Constructivism, Formalism and the host of other feverishly creative “isms” that have made Russian Modernism so powerfully influential in world art. In the winter of 1913-1914 the Futurists, with whom Mayakovsky identified, had toured Russia, reading their work to large and sometimes hostile audiences. Mayakovsky, with his huge build, huger voiceand flamboyant clothes, was himself a “slap in the face of public taste”, (the title of a Futurist manifesto) and revelled in the role, which he went on to combine with his own unique formulation of the unfallen spirit of the revolution.

His extremely personal style was developing rapidly. He hated “fine writing”, prettiness and sentimentality, and went to the opposite extreme, employing the rough talk of the streets, deliberate grammatical heresies and all kinds of neologisms, which he turned (inHVM) into a compendium of revolutionary rhetoric aimed at aesthetic victory in the class war. He wrote much blank verse, but also made brilliant (almost untranslatable) use of a rich variety of rhyme schemes, assonance and alliteration, creating complex patterns. His rhythms are powerful but irregular, departing from the syllabo-tonic principle of Russian versification, and based on the number of stressed syllables in a line, rather like Hopkins’s dynamic-archaic “sprung rhythm”, and influenced by Whitman and Verhaeren. In his public readings, he would often declaim in a staccato “that’s what” take-it-or-leave-it style, indicated typographically by the use of very short lines, spilling down the page in a distinctive “staircase” shape which also turns into a narrative principle, analysed by Victor Shklovsky:b

Hey, you!

You fine fellows who

Dabble in sacrilege

In crime

In violence!

Have you seen

The most terrible thing?

My face, when

I

Hold myself calm? c

Strangely akin to modern rock poetry in its erotic thrust and bluesy complaints and cries of pain, not to mention its sardonic humour, Mayakovsky’s poetry is aggressive, mocking and tender all at once, and often fantastic or grotesque. His imagery is violent and hyperbolic – he speaks of himself (for example) as “vomited by a consumptive night into the palm of Moscow”.dThe figure of Mayakovsky himself towers at the centre of his poems, martyred by fools and knaves, betrayed by love, preposterous or tragic, abject or heroic, but always larger than life, a giant among midgets. Characteristically, his first book, a collection of four poems published in 1913, was called “Ya” (“I”). In his “autobiographical tragedy”Vladimir Mayakovsky(1913), he portrayed the poet romantically as a prophet in heroic conflict with the banality of everyday life (the Russian word for this is “byt”, and it recurs in his suicide poem.) It played to packed houses despite exorbitant ticket prices. After the revolution, Mayakovsky’s poetry, like Meyerhold’s theatre, spoke directly to huge proletarian audiences. It was Meyerhold who staged (in 1918) Mayakovsky’sMystery-Bouffe, a typically subversive and blasphemous rewriting of the story of Noah reaching his promised land. The epic narratives of travel and escape that figure so prominently inThat’s Whatare prefigured in the epic (or mock-epic) poem about American interventionism entitled150,000,000(1919-1920), in which the folk-hero Ivan fights a hand-to-hand battle with Woodrow Wilson, resplendent in a top hat as high as the Eiffel Tower. Folk tale and political satire fuse in the name of the proletariat (the hundred and fifty million Soviet citizens.)

His most popular poem among present-day Russian readers, however, is undoubtedly the pre-revolutionaryOblako v Shtanakh(The Cloud in Trousers, 1915). Its dramatic gestures of despair at being rejected by Maria, his lover, (actually a composite figure), prefigure the more complex and extended masochistic narratives of humiliation and defeat inThat’s What. In both poems the poet’s suffering grows to become a paradigm of all the rejection and dispossession in the world, and his rage swells to encompass art, religion and the entire social order, until he is threatening to bring the whole world crashing down in revenge for his failure in love, and the social conspiracy which has cheated him of the object of his overwhelming (Oedipal?) desire. The intensity of these emotions carried him close to madness, and found its “objective correlative” in the creative and destructive energies of the revolution. George Hyde discusses in hisPrefacethe intermittently happy, ultimately destructiveménage à troishe conducted with Osip and Lily Brik, recorded in painful detail in a recent play by Steve Trafford,A Cloud in Trouserseand echoed in many sequences ofThat’s What. She did not reject him, but neither did she reciprocate his immoderate love, or give up other admirers. For sixteen years Mayakovsky publicly lamented Lily’s coldness and inconstancy, beginning just a few months after their first meeting withThe Backbone Flute(1915). But what hereallywanted from her, at the end of the day, it would be hard to say.

All of this disproportionate, insatiable orality helps us to understand why Mayakovsky welcomed the Russian revolution as “my” revolution and why he resisted (as he does inThat’s What) the reforms introduced by Lenin when the communist leader recognised that (to put it bluntly) Soviet Socialism, which seemed such a good idea and had cost so much in ruined lives and shattered dreams, did not actually work. We may discover here also why the equally unwelcome “reforms” of Stalin’s first Five Year Plan (1929), an act of naked authoritarianism, should have supervened destructively upon Mayakovsky’s erotic confusion and prompted his suicide in 1930. During the 1920s he had made several trips abroad, including a long visit to America in 1925, which might be interpreted as a hopeless bid to escape from Lily, and where a new love affair climaxed with the birth of his child. Like Hart Crane, Mayakovsky wrote a poem extolling Brooklyn Bridge as the great symbol of modernity and the free human spirit, but he was also deeply troubled by the social inequalities and the racism he found in the America of the time. On his return to the USSR after two years, he wrote the long poemKhorosho!(Okay!), a sincere tribute to his communist homeland, while his relationship with Lily continued to form an inexorable counterpoint to everything else, weaving its way through his urbanism, his political commitments and his self-dramatising scrutiny of the creative process. The intensity of the desire formulated in the earlier poem with the Russian titleLyublyu– the word for “I love”, containing the letters that spell the name of his beloved, Lilya Yurevna Brik – is complemented now by the agonising parables of separation and betrayal ofThat’s What.

Lenin’s New Economic Policy provided rich material for satire for Mayakovsky as it did for Bulgakov and others. It produced a cavalcade of crooks, hypocrites, speculators andagents provo-cateurs, and its general emphasis on improved living standards gave a new seal of approval to the Soviethomme moyen sensuel. Mayakovsky leaped enthusiastically upon this new specimen of humanity and created in his Prisypkin (The Bedbug, 1928) a wonderful addition to the gallery of Russian grotesques that began with Gogol early in the nineteenth century and turned into one of the great literary pantheons of all time. The bug-ridden, vodka-soaked Prisypkin is the personification of the vulgarity of the new Soviet man emulating the debauched ways of the bourgeoisie. At the climax of the play, in an apocalyptic conflagration, firemen’s pumped water freezes and Prisypkin with it. He is revived in the utopian society of fifty years later, having lost none of his stupidity and vanity. This “born again” motif, parodied from Christianity, features in a quite startling way inThat’s Whatas well, in the very specific form of “resurrection” by blood transfusion – one of the (numerous) aberrations of Soviet medical research was the belief that people might be made immortal by this means. The play that followed,The Bathhouse, (1930), is a merciless satire on Soviet bureaucracy, with parodies of meaningless socialist jargon that caused great offence. A month after the first performance, Mayakovsky killed himself, playing Russian roulette with a single bullet…