Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Cinnamon Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

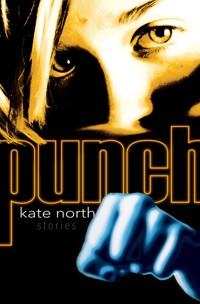

Punch is a collection of stories exploring the uncanny, the uncomfortable and the surreal in the everyday, at home and abroad. Whether it's a man with a growth on his hand, a couple trying for a baby, a woman finishing a book, a pope with penis envy, or a bullied girl, characters throughout the collection assess their surroundings and are often forced to reassess themselves. Punch offers the reader a humorous and disturbing take on life in the twenty-first century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 171

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Dedication

Epigraph

Mask

The New Tent

Lick

Beaujolais Day

Houtsiplou

Pope Penis IX

Punch

The Wrong Coat

All the Museums

The Largest Bull in Europe

Roundabout

On Holiday with Richard Burton

Black and White Buttons

Ms H and Me

Fifteen Arthur Crescent

PUNCH

KATE NORTH

Published by Cinnamon Press

Meirion House

Tanygrisiau

Blaenau Ffestiniog

GwyneddLL41 3SU

www.cinnamonpress.com

The right of Kate North to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988. © 2019 Kate North. ISBN 978-1-78864-086-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP record for this book can be obtained from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publishers. This book may not be lent, hired out, resold or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published, without the prior consent of the publishers.

Designed and typeset in Garamond by Cinnamon Press. Cover design by Adam Craig © Adam Craig.

Cinnamon Press is represented by Inpress and by the Welsh Books Council in Wales.

The publisher acknowledges the support of the Welsh Books Council.

Acknowledgements

For the space to write and kind hospitality; the Zuninos and the Briggs’s. For the support and encouragement, my friends, family and colleagues. For inspiration and enthusiasm, my students. For helping me keep things in perspective, Professor Aneurin Jenkins. For all of the above and so much more, Dr Alex and George.

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Peter Owen Publishers for permission to use the quotation from Anna Kavan.

Many of these short stories have previously appeared in other publications: Wales Arts Review, The Lonely Crowd, Secondary Character and Other Stories, A Flock of Shadows: New Gothic Fiction, American British and Canadian Studies, New Writing, The Lampter Review, Meniscus and High Spirits: A Round of Drinking Stories.

For Alex and George

Sometime, I suppose, I may forget the leopard’s visit. As it is I seldom think of him, except at night when I’m waiting for sleep to come.

Anna Kavan

Mask

Sarah noticed the mask as soon as she arrived at the farmhouse and the owner showed her around. She hated the way its eyes followed her about the dining room. Sarah could see it lingering in her peripheral vision as the owner was talking her through the cutlery and the crockery. Then, when she was being shown where the keys to the Citroën were kept, she watched the mask’s reflection wobble across the glass of the patio doors.

The owner drove off in her yellow people-carrier. Sarah waited a few minutes before making her way back to the dining room to have a closer look. She lifted the mask from the nail on which it was hung and was surprised by its lightness. It was made of papier-mâché. She had expected it to be ceramic or even carved stone. The mask had been painted with acrylics. Its gypsy persona had huge buggy eyes and a funny little mouth like the silhouette of a fat butterfly mid-flight. It wore a ring in its nose and a delicate little headdress.

Sarah spent the rest of the afternoon unpacking and picking up supplies from the nearby high street. By early evening she was ready for a snack. As she carried the bread and cheese into the dining room, she yelped and actually did a little jump upon seeing it again. She could not spend two weeks in its company. She took it off the wall and laid it face down on the sideboard. There.

The routine of writing soon took over (early morning before it gets too hot), cat feeding (twice daily, don’t forget the medicated pâté for its tummy problem), plant watering (tomatoes, herbs and fruit trees, don’t worry so much about the shrubs) and mindfulness meditation (early evening before making dinner) and it had been three or four days before Sarah noticed the mask again.

She had come back from a trip to town on the wrong bloody bus. She had been around the périphérique twice. She really needed the loo by the time she got in. She was so desperate she ran straight inside, leaving her bags in the courtyard and her keys in the front door. Coming out of the bathroom she saw it, back on the wall where she had certainly not placed it. It was a cloudy day and the light gave it a sullen sheen.

‘Good afternoon,’

Sarah heard the words and watched the mask’s lips flutter. Although she knew what she had witnessed she refused to associate the sound with the movement. She stood still and eyed the mask while trying to breathe more slowly than the beat of her pulse.

‘Good afternoon,’ said Sarah, shocking herself.

The mask smiled. Sarah stepped towards it slowly, reaching forward with her right arm. She did not know what she was doing but she felt compelled, nonetheless. Her hand caressed the circumference of the mask and she placed her thumb on its smile. It felt like the smooth corners of a cardboard box.

It looked traditional, sort of ethnic. It looked like the type of mask you learn about at a provincial museum in the mountains of Spain, Poland or Mexico. There would be a little corner of the museum where an old lady would be working away on her own masks while people watched. On certain days she would hold workshops where visitors could join in and make their own papier-mâché masks. The masks would represent something like fertility, good fortune or happiness and they would traditionally have been made for special occasions like weddings, or the birth of a child.

Sarah felt a deep heat in her thumb throb outwards, radiating across her hand and up her wrist. She looked down to see the mask’s lips close around her thumb. Her pain grew as its lips pulled back to show Sarah the row of small, yellow teeth like corn, digging into her flesh. She shrieked and shook her arm in an effort to get rid of the thing. It would not let go. The mask started to growl, a deep, low, scratchy sound that caused Sarah’s hand to vibrate. She began beating her hand against the stone wall in desperation. After three cracks against the wall the mask released its grip and fell to the floor. It lay still and Sarah kicked it with the side of her shoe. Nothing. She kicked it again. Nothing. She flipped it over with the toe of her shoe and it faced her. She noticed the nose had caved in.

She felt stupid. And a little hot. Perhaps she was coming down with something? She hoped this more than believed it. She looked at her thumb, a ring of indentations circling it. She looked to the mask, still, silent, its nose a crumple. She crouched directly over it. The mask’s eyes were dead.

A woman stood in the doorway to the dining room. She was watching Sarah crouched on the flagstone floor, staring intently.

‘Bonjour Madame,’

Sarah stood up and faced her.

‘Bonjour,’

‘Je suis la femme de ménage, Madame Kitoun.Ça te va bien?’

‘Oui, ça va.’

Madame watched as Sarah scuttled away, climbing the stairs to the loft of the house.

Sarah could hear the cleaning lady downstairs. First she did the hoovering, then she did the mopping. According to the owner, she only did the floors one week then the polishing the following week. She would be gone soon. Sarah’s French was basic and she didn’t want to suffer a conversation. Anyway, what on earth would she say to the woman? That the ornamental mask, with its nose now bashed in like a piñata, is possessed? Sarah thought of Thing from The Adams Family scuttling about like a spider. Perhaps the mask was mobile. Maybe it could roll itself about, as Aristophanes described. It probably couldn’t climb the stairs though. It had no limbs, of course. Sarah waited until the cleaning lady had gone and then waited another half hour out of fear, before she headed downstairs slowly, listening as she crept.

The mask was back on the wall. Sarah didn’t want to touch it again. She wondered if the cleaning lady would speak with the owner. Her hand was balled into a fist. It still hurt, though no blood had been drawn. There were red marks around her thumb still. She didn’t take drugs, aside from the Diazepam in her toiletry bag. Her doctor had prescribed them for the flight. She thought about taking one to calm down then dismissed the idea. It wouldn’t help.

She needed a box with a lock. She searched the garage, then the shed and the kitchen. She found a lidded wicker basket and a padlock that she managed to attach to it. She placed the basket on the floor beneath the mask and then got a broom from the utility room. With the pole of the broom Sarah flicked the mask off the wall, bashing the side of its face this time. She rolled the basket onto its side, opened the lid, then coaxed the mask in with the broom. As she shut and locked the lid, the basket began to shake. Sarah screamed and stepped back. The basket became still. She pushed the basket towards the front door using the head of the broom. Once outside she unlocked the Citroën. She opened the boot, took a deep breath and, in one swift movement, picked up the basket and threw it into the car. With that she slammed the boot shut and waited for a moment. Nothing moved. She locked the car and went back inside the house.

That evening she opened a bottle of Chinon and drank it with a big, fat steak and the evening sunset. She had needed to get away for a while.

She was never able to finish a project at home. She was working on a book about British wildflowers. The photographer was still sending her pictures. He was very talented. There were some lovely shots of the Angel’s Trumpet before and after flowering. The difference was tremendous, one moment it was a spiky, succulent ball of green, like an obese sea urchin, then, when it opened, it became a ghostly flare. The one in the picture was white but they come in many colours like pink and red and purple.

Every time she thought she had received the last picture he would send another. They would need to talk soon so that she could set a firm limit. She wondered if she should speak to the photographer directly or go through her editor, Pippa. Obviously, the book needed to be as comprehensive as possible, but it was becoming an ever-expanding project and she feared it would soon turn into a rushed catastrophe.

She loved the crazy names of some of the flowers, like Bastard Cabbage, Perennial Candytuft and Hooker’s Fleabane. She was trying to be as poetic as possible with her descriptions. That’s why she took the commission. She had made a name for herself with her last book on clouds. (She found she had liked working with photographs.) The flower project seemed a logical progression, but she was struggling with a title. It couldn’t just be British Wildflowers, it needed a catchy subtitle alongside it. Her working title was currently Wild British Flora: a lyrical catalogue. She knew it was a bit pretentious.

Over the next few days she planned to cover the Poppy, Netted Iris and Jacob’s Ladder. Then she emailed Pippa to confirm their call later. She had been thinking more about the book’s structure. Perhaps, where there were many variations, such as with the Honeysuckle genus, she could concentrate on her favourite species, in this case Henry’s Honeysuckle. Then she could go on to cover the rest briefly. She was hoping the publisher would go for this, but she was aware they might prefer a more straightforward approach. They may want her to go on from the genus of Honeysuckle to the species and varieties, but she felt this approach was less personal. The cloud book had been a success precisely because of its personal touch. That was what all of the reviewers had said.

When it came to the Poppy, it had lovely varieties. Her favourite was the simple Common Poppy. Then the yellow Welsh Poppy, the bulbous Opium Poppy, the splayed Prickly Poppy, all with their attractive elements, but the Common Poppy remained the most elegant to Sarah’s mind. Perhaps it was because of the associations it held. She imagined nodding fields of red, wind blowing a mass of flowers as rain came in. Maybe her next book could be about rain, she thought.

In trying to describe the Common Poppy Sarah was attempting to nail the colour. She had managed the stiff stalk hair, but the colour was harder to achieve. She had thought that honey-red might do for a while but it was livelier than that. She pulled the picture of the Common Poppy up on her screen.

The curve of the petals put her in mind of the mask’s fluttering lips and the hairs on the back of her arms raised. The mask was still in the car outside. She hadn’t checked on it since locking it in the boot four days ago. Whenever she remembered it, while cleaning dishes, or doing stretches before jogging, she felt a little queasy and tried to block it out. She was concerned about what to do with it at the end of her stay. She couldn’t leave it in the car.

Her thumb was no longer marked from the bite but she remembered the nipping pain. She felt it earlier when unscrewing a jar of jam. It assured her she had not imagined the incident. Realising this she suddenly felt empty and light, inconsequential and fleeting, like the husk of a flower, a poppy, petals gone, faded seed-head rattling in the breeze. Part of her wanted to put that description in the book. Perhaps she could work the idea into her introduction.

She minimised the poppy picture and saved her description thus far. A clearer mind would do better tomorrow. It was time to talk to Pippa anyway. She opened the Skype app and called her.

‘Hello, hello,’ said an electrified voice through an amorphous blob of pixels on the screen.

‘Can’t see you darling,’ said Sarah to the blob.

‘Can’t see you either,’ said the blob.

They tried a couple more times and then suddenly they were in focus, voices clear. She was really happy with what Sarah had sent through this past week.

‘Gorgeous, just gorgeous. When do you think you’ll be done?’

Sarah explained about the photographer and all of the photos. A limit needed to be set. She only had another week here and she wanted to have the book completed by the time she left. There were six more entries to write. She didn’t really want to do any more than that. Then there was the introduction. Pippa said she would speak with the photographer, see if she could calm him down a bit. He had read Sarah’s cloud book and was very happy to be part of the project.

‘And after this? Any plans?’ Pippa had asked.

‘No. Maybe a break.’

‘Something interesting has come in.’

‘Oh, yes?’

‘I thought of you. It’s on masks.’

Sarah stared into the screen but didn’t speak.

‘What do you think?’

‘Masks?’ she mumbled.

‘Yes, traditional ones, African ones, Korean ones, Venetian ones. All sorts.’

Sarah was too shocked to say anything.

‘Well, you don’t have to decide now,’ said Pippa. ‘Have a think.’

Sarah could feel herself starting to perspire.

‘I can’t see you,’ she lied. ‘You’ve gone.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Pippa.

‘Hello?’ Sarah enquired, though she could see Pippa clearly. ‘You’re all pixelated and foggy.’

‘I’ll speak to the photographer and email you. We can talk again next week.’

‘Okay. Bye.’

Sarah closed her laptop. She was shaking. A book on masks? No way.

The next day, Pippa emailed. She had spoken to the photographer, who only planned to send another two pictures, of Garden Lupin and Corn Mint. Sarah agreed to the final two and was satisfied she could squeeze them in. There was no further mention of the mask book. She had been trying to think of an excuse to say ‘no’.

The British lady wasn’t in when Madame Kitoun returned. There wasn’t much mess and she was through with her polishing quicker than usual. She did notice that there had been another incident with the mask though. There it was on the floor again. Face down on the flagstones. A bit odd. Perhaps the nail in the wall was loose. Madame Kitoun bent down and gave it a brush with her duster. She looked at its caved-in nose and sighed, placing it on a side table. It probably wasn’t worth saying anything to the owner. She left a note on the dining table to say that she had called and to wish the lady a bon voyage. Sometimes people left her a tip at the end of the week. Madame noticed that the tips increased after she started leaving goodbye notes. There would be ten euros and pour madame scrawled across a note or on the back of an envelope.

Sarah was taking a day off. She had written each entry and made a fair stab at the introduction. She was happy to finish the rest at home. She decided to treat herself to a dress she had seen in the first week. It was in a little boutique in the old part of town by the cathedral. It was more expensive than she would usually pay but she had worked hard this past fortnight. She bought herself a bottle of champagne too and even took a cab back to the house. She was going to enjoy her last night.

She had done this last time, buying champagne to mark the first draft of her cloud book. She was going to make it a tradition, like in Stephen King’s Misery, she thought. Though she wouldn’t smoke a solitary cigarette with the drink, being too scared that she may start the habit again.

She was in the hallway and she could immediately tell that someone else had been in the house. The cleaning lady. The air smelled waxy with polish and the mirror by the front door shone.

When she walked into the dining room she saw it straight away. The champagne neck slipped through her hand and the bottle crashed to the floor. Liquid ran through the grooves between the flagstones. Glass twinkled in the evening sun that glowed through the patio doors. She stood for some time staring at the mask, too scared to move. She must have stood like that for a good five minutes before going to get the broom. After sweeping the glass into a carrier bag, while keeping an eye on the mask, she gave the floor a rudimentary wipe with a cloth. Then, grabbing the broom again she crept towards the mask, holding the broom straight out like a lance. She prodded the mask with the broom and nothing happened. She walked backwards, facing the mask as she backed out through the dining room door. She was lucky the door had a key. She slammed and locked it.

That evening she finished her packing. She had intended to try on the dress again and then drink her champagne with dinner in the garden. Instead she bolted her food in the kitchen and retrieved the empty basket and padlock from the boot of the Citroën. She took five Diazepam. They were only two milligrams each, she told herself, and lay on the bed with a compress on her forehead. She tried to practise her mindfulness but the mask loomed in her thoughts.

The next day she set her luggage in the courtyard and sat on her red case, waiting for the taxi to the airport. It pulled in and the driver got out making for her suitcase. She nodded towards the house and said, ‘Un moment?’ The driver replied, ‘Oui,’ and began loading her bags.