Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

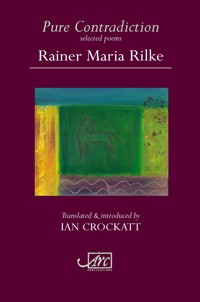

"Not a poet, but the embodiment of poetry." Maria Tsvetaeva Rainer Maria Rilke's work spans the divide between the decadence of early 20th-century Europe and the modernist revolution that followed the First World War – always struggling to develop, to seek and reach beyond itself. This selection brings together poems from throughout Rilke's career, placing poems of similar themes close to one another, making bed-fellows of poems rarely seen together, and catching Rilke's blend of crafted sensuality and spiritual searching. "Along with Charles Baudelaire, Rilke is the foremost poet of the erotic from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But there is much more to Rilke's poetry than eroticism... Rilke was nothing if not ambitious with his poetic vision." Raymond Humphreys "New translations of Rainer Maria Rilke must always be welcome... The power of this poetry is to a great extent in its new angles, but, more important routes to new depths." Stella Stocker, Weyfarers Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) witnessed the radical new art emerging in Paris before the First World War, meeting Rodin, Picasso and Tolstoy and many other artistic giants of the time. Together with letters and his novel The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, Rilke's poetry constitutes one of the great literary achievements of the 20th century. Ian Crockatt is a Scottish poet. His Original Myths (Cruachan, 2000) was shortlisted for the Saltire Society's Scottish Book of the Year Award in 2000. This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 114

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Pure Contradiction

Published by Arc Publications,

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road

Todmorden OL14 6DA, UK

www.arcpublications.co.uk Translation copyright © Ian Crockatt, 2012

Introduction copyright © Ian Crockatt, 2012 Design by Tony Ward 978 1906570 22 4 (pbk)

978 1906570 44 6 (hbk)

978 1906570 44 6 (hbk)

The translator gratefully acknowledges the award of a writer’s bursary by Scottish Arts Council to enable the completion of this project, and the permission granted by Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, for the use of the German texts.

Cover painting by Wenna Crockatt

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part of this book may take place without the written permission of Arc Publications.

The publishers acknowledge financial assistance from ACE Yorkshire‘Arc Classics: New Translations of Great Poets of the Past’

Series Editor: Jean Boase-Beier

RAINER MARIA RILKE

Pure Contradiction

Selected Poems ~

Translated and introduced by

Ian Crockatt

2012

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In making these translations, I have freely consulted other translators’ work, particularly that of Stephen Mitchell, Edward Snow and Stuart Cohn; but also including J. B. Leishman, C. F. McIntyre, Michael Hamburger, David Oswald, Don Paterson, Jo Shapcott and A. Poulin, Jr. My thanks to them all.

At the same time I have tried to bear in mind Gerald Manley Hopkins’ practice regarding other peoples’ work: “admire, and do otherwise”.

Some of these translations were published first in Northwords Now.

Thank you to Stuart B. Campbell and Philip Wilson who read the translations in manuscript and commented constructively and in detail on the many shortcomings they found – those that remain are solely mine.

Thanks also to Jean Boase-Beier and George Szirtes respectively for their encouragement; to my brother Richard who started all this by introducing me to Rilke and who has generously supported me throughout; and special thanks and love to Wenna who weathered the “Rilke years” with a tolerance I hardly deserved.

Ian Crockatt

CONTENTS

Introduction

Le Ruban

•

The Ribbon

Ich liebe meines Wesens Dunkelstunden

•

I Love my Nature’s Darkest Hours

Eingang

•

Entrance

Früher Apollo

•

Early Apollo

La Fontaine

•

The Fountain

Da stieg ein Baum. O reine Übersteigung!

•

A Tree Rose Up. – O Pure Transcendence!

Die Gazelle

•

The Gazelle

Spanische Tänzerin

•

Spanish Dancer

Geburt der Venus

•

Birth of Venus

Ausgesetzt auf den Bergen des Herzens

•

Exposed on the Mountains of the Heart

‘Man muß sterben weil man sie kennt’

•

‘We must die because we know them’

Dich, die ich kannte wie eine Blume

•

You, Whom I Knew Like a Flower

Leichen-wäsche

•

Washing the Corpse

Requiem für eine Freundin (extract)

•

Requiem for a Friend (extract)

Der Tod

•

Death

Klage

•

Lament

Und fast ein Mädchen wars

•

And It Was a Girl, Almost

Orpheus. Eurydike. Hermes.

•

Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes.

Der Turm

•

The Tower

Begegnung in der Kastanien Allee

•

Encounter in the Chestnut Avenue

O dieses ist das Tier, das es nicht giebt

•

O This is the Animal That Cannot Be

Du, Nimmergekommene

•

You, Never-arriving One

Liebes Lied

•

Love Song

Die Entführung

•

The Abduction

Leda

•

Leda

Abschied

•

Parting

Die Genesende

•

The Convalescent

Christi Höllenfahrt

•

Christ’s Descent into Hell

Duineser Elegien: Die Erste Elegie

•

Duino Elegies: The First Elegy

Am Rande der Nacht

•

On the Verge of Night

An die Musik

•

To Music

Gong

•

Gong

Ein Gott vermags. Wie aber, sag mir, soll

•

A God Can Do It. But You Tell Me How

Der Einsame

•

The Solitary

Du siehst, Ich will weil

•

You See, I Want a Lot

Bildnis

•

Portrait

Duineser Elegien: Die Vierte Elegie

•

Duino Elegies: The Fourth Elegy

Irre im Garten

•

The Asylum Garden

Siehe die Blumen

•

Look at the Flowers

Ô Lacrimosa

•

O Lacrimosa

Sei allem Abschied voran

•

Be Ahead of All Parting

Le Foulard Rouge

•

The Red Scarf

Notes

Biographical Notes

INTRODUCTION

During his lifetime Rainer Maria Rilke was revered by poetry lovers throughout Europe. The Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva’s remark in a letter to him that he is “not a poet, but the very embodiment of poetry” captures the feeling. It seems that it still prevails, particularly amongst poets, if the continual stream of English language translations and commentaries by them is anything to go by – I have a dozen from the last sixty years or so next to me now, and there are more, as well as a generous scattering of single poem translations amongst other poets’ collections of their own work. Of course Rilke wrote so much poetry, and so much about his life, that it is unlikely that most of us have read all of it. Most have translated selections from his books, or have focused on particular ones – Duino Elegies, Sonnets to Orpheus, New Poems, The Book of Hours, The Book of Images, poems not published by Rilke in his lifetime, and his French language poems being the main groups.

So why another? It’s not a question generally asked of the director of a new production of Hamlet, or the producer of a new CD of Beethoven’s ninth symphony – we accept that there is an infinity of interpretations possible of the most profound works of art; that is part of their greatness. In fact we constantly seek new approaches and insights which will further our understanding and appreciation of them, and so, we believe, of our own elusive natures. Much of Rilke’s work achieves this exalted level of mastery and appeal – many, for example, refer to the Duino Elegies as the highest achievement of twentieth-century poetry in any European language.

The purpose of this small selection is to add a particularity of approach to the corpus of Rilke translation and, by so doing, to illuminate the richness of language, thought and feeling it communicates from an infrequently explored angle. The focus is on interconnectedness, the sense that the poetry, letters and prose Rilke produced in such enormous profusion throughout his life, are developments – variations, diversifications, departures – of and from the idiosyncratic set of ideas and themes he arrived at when he was a very young man. This is best illustrated by the discussion developed later in this introduction about the order in which the poems are arranged in this volume, and examples of how some, though written twenty or more years apart, can gain from relation with each other.

One idea in particular which Rilke frequently expresses in words, but which he also physically and emotionally lived, is that there is a basic conflict between life, in its bourgeois forms in Europe, and the work of a purely dedicated artist – to be the one he had to sacrifice the other. Even in a post-modern age which would rather take the text for what it is than approach it as a product of its writer, this makes Rilke’s biography of unusual significance to his art. I therefore think that before discussing the arrangement of the poems in this selection, and the reasons for it, a brief overview of the external features of his life, and some links between it and his writing, will be helpful.

Rilke – christened René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria – was born in Prague in 1875, a time when Prague was part of the Austrian empire. Rilke’s family was part of the minority but dominant German-speaking elite, contemptuous of their Czech neighbours, but neither rich nor high in status. His father was invalided out of the army before achieving his ambition of gaining a commission, and lived a life of disappointment working for the railways. His abiding hope was that his only son would gain distinction in the army instead. The family had notions of being descended from an aristocratic strain of Rilkes, and René never lost the air and pretensions implicit in this (mistaken) belief. The force in his family was his mother, who was religious, sentimental and theatrical, and had snobbish ambitions for her son. Her apparent disappointment that he was not a girl – an older sister had died in infancy – plus his delicacy, resulted in him being brought up as one for his first five years; and yet, his parents having separated when he was 9 years old, he was bundled off to a military school by his father when aged just 11. Rilke frequently refers to his five years of suffering there – he was finally allowed to leave on account of his poor health.

But by this time he was already writing, both poetry and prose, as well as involved in the production of plays and other literary projects. Between 1892 and 1896 he seems to have been an embarrassingly eager, over-prolific, fay and frequently derivative writer, a character in Prague literary circles who could sometimes be seen walking the streets in contemplation of an iris held in front of him. Nevertheless his work, in particular his poetry’s brand of quasi-religious heightened sensibility and its technical virtuosity, attracted attention – by the age of 21 he had already published three books of poetry, as well as stories and novellas.

From these beginnings an immensely individual and uncompromising writer emerged, one who committed himself so completely to his art that serving it, making himself available to its demands, creating the optimum conditions for uninterrupted response when real inspiration arrived, took priority over commitment to relationships and sustained human intercourse. His marriage in 1901 to Clara Westhoff, a sculptor pupil of Rodin and member of an artist’s colony in Worspede, Germany, lasted a lifetime in the sense of continuing contact, but only a few months of actually living together. Rilke had to sacrifice the conventional benefits and comforts of living a domestic life with his wife and daughter, to the nomadic, emotionally and sexually uncommitted life of the committed artist. As his work increasingly made him famous his many liaisons with women – some rich and generous patrons – his wanderings between their houses, hotel rooms and briefly rented flats throughout Europe – punctuated by begging letters to his ever-indulgent publisher as well as production of his increasingly successful books – allowed an outwardly shapeless and yet utterly purposeful life dedicated to his art to develop.

Paris, where he based himself in his earlier days, was of particular importance to Rilke, and it was a city he both feared and loved. His only novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, painfully written over a period of six years, gives an extraordinary, hallucinatory account of the near breakdown of a sensitive psyche in the face of the heartbreak and grotesquery of its street-life. He made two trips to Russia with Lou Andreas-Salomé, the fascinatingly intelligent and beautiful woman who was one of the first of her gender in Europe to attend university, was wooed unsuccessfully for three years by Nietzsche, and who, in later life, became a friend of Freud and one of the first psychoanalysts. It was Lou – for a while Rilke’s lover – who was responsible for Rilke changing his name from René to Rainer. She, and through her Russia, remained important to him throughout his life. So too did Rodin, the sculptor he regarded as Europe’s foremost artist and to whom he was secretary for two years. Through observing Rodin’s single-minded absorption in his work, and the ferocity of his concentration whether or not he felt ‘inspired’, Rilke developed a new focus and physicality in his writing. This new engagement with Things, the attempt to internalise the inner essence of objects and re-express them through the subtly tuned medium of his inwardly focused poetry, is most clearly demonstrated in the 180 or so poems which make up the two volumes of New Poems, published in 1906 and 1908.

Rilke’s ability to change his work in response to the influences and circumstances currently at play is not, however, either instant or superficial. Once he had written ‘Panther’, his famous first New Poem after following, it is said, Rodin’s advice to go to the zoo and observe, he continued to produce poems in his earlier style. It was a further two years before he set to work to develop this new approach which so fundamentally underscores his later work, as well as sounding a substantially new note in European poetry. Later, in 1912, while staying alone at Duino Castle on the Adriatic sea – it belonged to his supporter and patron Princess Maria von Thurn und Taxis-Hohenlohe – he ‘received’ the first lines and overall scheme of what he knew was to become his great work, lines redolent with a sonorous intensity and expansiveness of understanding and purpose new to him and yet, all his life, anticipated. Nevertheless it was another ten years before he was able to find the physical place, the undisturbed time and the repose of mind which were the conditions he knew he required to finally complete – in an overwhelming few days which he described as ‘a hurricane of the spirit’ – not just the ten Duino Elegies, but also the entirely different, unexpected, series of fifty five exquisite Sonnets to Orpheus