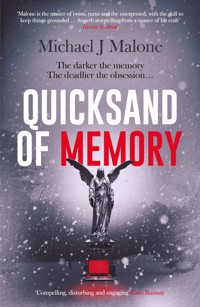

Quicksand of Memory: The twisty, chilling psychological thriller that everyone's talking about… E-Book

Michael J. Malone

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Scarred by their pasts, Jenna and Luke fall in love, brimming with hope for a rosy future. But someone has been watching, with chilling plans for revenge … An emotive, twisty, disturbing new psychological thriller by the critically acclaimed author of A Suitable Lie and In the Absence of Miracles. 'Compelling, disturbing and engaging' Caro Ramsay 'Malone is the master of twists, turns and the unexpected, with the skill to keep things grounded … a master of his craft' Herald Scotland 'Tense, pacey and lyrical … cements Malone in the firmament of Tartan Noir, marrying McIlvanney and Banks to a modern domestic noir that'll have you reading into the wee sma' hours' Ed James ______________________ The darker the memory, the deadlier the obsession… Jenna is trying to rebuild her life after a series of disastrous relationships. Luke is struggling to provide a safe, loving home for his deceased partner's young son, following a devastating tragedy. When Jenna and Luke meet and fall in love, they are certain they can achieve the stability and happiness they both desperately need. And yet, someone is watching. Someone who has been scarred by past events. Someone who will stop at nothing to get revenge… Dark, unsettling and immensely moving, Quicksand of Memory is a chilling reminder that we are not only punished for our sins, but by them, and that memories left to blacken and sharpen over time are the perfect breeding ground for obsession, and murder… _______________________ 'Complex, human characters living in a page-turning world' Douglas Skelton 'Long-held secrets, complex relationships and an ever increasing sense of menace … fantastic' Steph Broadribb 'A fascinating exploration of damage, toxicity, trauma and love' Sharon Bairden 'Darkly compelling and provocative … from the outset, whiplike tendrils of disquiet creep their way into the story' LoveReading 'Masterfully combines the dark, cruel elements of people's lives and nature with a glimmer of light and hope' Fiona Sharp 'An almost perfect storm of circumstances that lead us to a dramatic and potentially deadly conclusion … an emotionally charged story' Jen Med's Book Reviews 'I can genuinely say: Fiction doesn't get any better than this' Book Review Café Praise for Michael J. Malone 'A beautifully written tale, original, engrossing and scary … a dark joy' The Times 'A complex and multilayered story – perfect for a wintry night' Sunday Express 'Vivid, visceral and compulsive' Ian Rankin 'A terrific read … I read it in one sitting' Martina Cole 'A deeply satisfying read' Sunday Times 'A fine, page-turning thriller' Daily Mail 'Malone's latest is an unsettling, multi-layered and expertly paced domestic noir drama that delves into one family's dark secrets, shame and lies' CultureFly 'Engrossing, hard-hitting – even shocking – with a light poetic frosting. Another superb read!' Douglas Skelton 'A dark and unnerving psychological thriller that draws you deep into the lives of the characters and refuses to let go. This is a brilliantly written book; I could not put it down' Caroline Mitchell 'A chilling tale of the unexpected that journeys right into the dark heart of domesticity' Marnie Riches For fans of Jodie Picoult, Gillian McAllister, Cara Hunter, Shari Lapena, Liz Nugent and Mark Edwards

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 472

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Quicksandof Memory

Michael J. Malone

Contents

Prologue

Fifteen years earlier

The boy was so cold he could hear his teeth knocking together. He was sitting on the floor of his tiny bedroom because his mattress, quilt and sheets were soaked through after his new foster mother had poured a bucket of cold water over them. An action she had taken with the expression of a beleaguered saint – See what you made me do.

He pulled his knees up to his chest in the empty hope it might gain him some heat. Then, despite the numbness in his fingers, he bent forward to have another shot at tying his shoelaces. Because untidy shoelaces were just one of the many things that sent his foster parents searching for a way to punish him. A smart appearance was the measure of the man, they said, so make sure your laces are tied neatly and that the loops aren’t any longer than the ends. Which was impossible to achieve when your hands were this cold. But he had to try, because if he didn’t, they’d know. Not trying was next to Godlessness, they said. And the punishment for Godlessness was … well, he didn’t know. He’d managed to avoid that sin. So far.

Being next to it was bad enough.

They were never violent. Not physically anyway. That was beneath them. Words were the currency of their punishment. A constant drip into the mind, letting you know that you were worthless and unloved.

Cold room.

Cold-water bathing.

Bedding doused in iced water.

Tiny portions of food from the fridge. Congealed with fat and often so dry it was hard to chew.

Still, when you’re not worth that much and you’re a burden on everyone, you deserve what you get.

Right?

He could hear a knock at the front door. Footsteps. The creak of hinges, and then a sound swelled into the space. Children singing. Even from here in the half-dark he could detect the pattern of a song about Christmas.

It would be children from his school, rounded up by the teachers to go carolling door-to-door to raise money for charity.

‘Oh, come and see this, dear,’ he heard the man say.

Footsteps, and the woman replied, ‘Oh, how cute,’ with a sing-song tone in her voice he’d never heard before. And in his mind’s eye he could see them arm in arm at the door. The image of the perfect, Christian couple.

He thought of the previous Christmas.

Before all of this.

Before that.

His big brother bounding into the house with a large holdall full of stuff. He couldn’t be bothered with wrapping, so you just got the toy or whatever in its box. Knowing what it was straight away didn’t detract from the pleasure. It was his big brother – his hero – giving him stuff.

‘Five minutes, some paper and tape. That’s all it takes,’ his mother said. ‘Keep the magic alive for the bairn, you arsehole.’

‘Did you nick that?’ his father demanded.

The talons of the memory ripped at his chest, seized his heart and squeezed. They reached into his gut and twisted and pulled and burned. A sense of near-crushing loss built up from his bowels. He felt his bottom lip tremble.

But he didn’t cry. Wouldn’t.

‘Big boys don’t cry,’ his new ‘mother’ intoned in his ear.

And he was proud that he managed not to.

He was a big boy now.

Right?

Chapter 1

Luke studied his diary. Two appointments today. None tomorrow, and two the day after that.

He was hardly winning at this new therapy business, but still, it was better than last week, when he’d had a total of two.

Slowly, slowly, his network of peers all told him. It takes at least a year to build up a business in alternative medicine. Don’t expect it to happen overnight. Perhaps the end of the year, leading up to the holidays, wasn’t the best time to launch a new practice.

All of it meaningful and well-intentioned advice, but he guarded against accepting it as The Truth, because if he lowered his expectations too much, he felt sure his new venture would fail, which couldn’t happen. He had bills he was struggling to pay and a child to feed.

Looking around his work space – essentially a posh shed in his small garden – he examined it as if he were a client. Would this suggest a successful practice?

A friend had given him an old table for a desk. He’d sanded it down and applied a light varnish that, instead of hiding the old stains, served to highlight them. But he liked that; it gave the table a worn look. See, it told his clients, I’ve been through a lot, but I’m still standing.

An old dining-room chair sat behind the desk, varnished in the same way. In the space in front crouched a matching pair of the most comfortable armchairs Luke had been able to find. They were second-hand, but the mechanism that allowed one of the chairs to tilt back was still in perfect working order. That and the soft grey mohair throw combined, he hoped, to make the client set aside their apprehensions about talking to a complete stranger and telling him their deepest fears.

In the other corner he’d set a small, sanded and painted coffee table with a jug and glasses, a kettle, cafetière and some mugs. So far people preferred water, but in between clients he found that at least for himself, coffee was required.

A few scattered plants and black-framed qualifications – nutrition, hypnotherapy, counselling, CBT – pinned to the walls completed the look. He’d debated whether or not he should have a picture of Nathan on his desk: thought it might be too cheesy, but then went ahead anyway. But with the image pointed at him rather than his clients.

He touched the photo briefly, over the boy’s smile, and felt warmed through by this simple action. Despite not being Nathan’s biological father there was a resemblance. Or so he liked to think. But there in the eyes was his mother, Lisa. Dead three years since. The breast cancer had been treated, but it came back with a vengeance. His throat tightened and he felt his eyes mist as he remembered those last days.

He had been there, at the end, along with her mother, Gemma. Both of them sobbing, unwilling to let go, unable to deal with the remorselessness of the disease. Lisa, pale as bleached bones. Graceful in her stoicism.

‘Something…’ Lisa gripped his hand ‘…that reassures me.’ Her smile was a tremulous thing, laced with fear but gilded with hope. ‘Nathan has you.’

‘Don’t,’ Luke had said. ‘You’re going nowhere.’ He bit his bottom lip. Be strong for her, he intoned in his mind over and over, like a mantra. ‘You’ll be there holding his hand, first day at school.’

Her eyes lit on his, and she poured strength into him. Strength and acceptance. ‘He’ll be skipping in the school gate,’ she said, her gaze off in the distance, seeking a golden future for her little boy. ‘I can see him. Excited. Swinging his wee bag, with his lunchbox and everything.’

‘Don’t,’ Luke said, unable to hold back a sob. ‘Please.’

‘You’re a good dad, Luke. The best. We’re so lucky to have you.’

‘No. Don’t. You’ll be there,’ he replied. ‘Every step of the way.’

She raised her eyebrows. ‘Better believe it.’ She managed a laugh. ‘Listen to the wind. That’ll be me whispering in your ear.’ Then she adopted a mock scolding tone. ‘Don’t let him watch too much TV. Once a month is fine for a Big Mac. And for goodness sake don’t buy him any more dinosaurs.’

They laughed through the tears.

She died sometime later. Her mother holding one hand. Luke the other.

Gratitude was the thing, she told him over and over on those last days, that will carry you through. At the time he’d refused to listen. Couldn’t listen. How could he be grateful when she was dying? But now he saw the sense of it. Now he could be grateful she’d been in his life, that she’d pulled him from the fire. The only person who knew everything about him, everything he’d done, and still she loved and trusted him. He was a better man for her affection and attention, and for that he would be eternally thankful.

There was a knock at the door.

A single contact.

Getting maudlin there, Luke, he scolded. He rubbed at his eyes. Took a deep breath. Time to get to work.

There was a louder double knock,

Luke looked at his diary to remind him of the client’s name. Jenna Hunter. She’d booked online and filled in the notes to say she was dealing with crippling anxiety following a relationship break-up, and the chronic and complicated ill-health of her mother.

‘Just be with you,’ he shouted. And he walked to the door, excited to be seeing someone new. Excited to be in a position to offer to someone else the help he’d needed to rebuild his own life.

Chapter 2

Jenna looked around herself. This wasn’t necessarily an area she would have expected a therapist to live and work in. A modest street with small, one-bed bungalows on one side and what she guessed would be mainly ex-local-authority houses on the other. The house she was visiting looked like it would be one of the latter. A narrow end-of-terrace with one window, top and bottom, facing the street, the render painted white. The garden was small, but the grass was trim and planters crammed with winter flowers dotted here and there offered splashes of colour.

She’d followed the instructions on the website, walked in the gate, down the path, around the side of the house and down the garden to what looked like a prefabricated outbuilding that nestled under a giant fir hedge.

It hardly screamed ‘thriving business’, but the fees were relatively low, and the guy’s website was full of glowing testimonials.

At the door she raised a hand to knock. Then she allowed it to fall as she turned away.

What was she doing? She wasn’t the kind to see a therapist, surely?

Then the heaviness she felt every morning when she woke from a fractured sleep filled her mind. Butterflies with ice-tipped wings rose and fell in her gut, and her heart sent out a loud and fast semaphore of anxiety.

She couldn’t go on living like this. On the way over she’d fantasised about speeding up on a bend and crashing into a tree. Anything to stop the ceaseless monkey chatter of self-accusation that ran on a loop through her mind.

Before she could move away she turned and knocked. Then, thinking she couldn’t leave now, she knocked twice more.

The man who opened the door had a bright, friendly face. His dark hair was greying at the temples, and the few lines radiating from his eyes seemed hard-won.

‘Jenna Hunter?’ he said, and stepped back. ‘Come in. Have a seat.’

Jenna entered, spotted a low armchair that looked like it had been designed for a winter’s evening and a good book. She sat.

The man talked on:

Nice morning.

Mild for this time of year.

There’s a flock of sparrows in the hedge at the end of the garden, I hope they don’t chirp so loudly they disturb us.

The man seemed almost as on edge as she was. No, she thought, as she looked into his face. Not on edge. Keen. Anxious to be of help. And that keenness silenced some of her doubts.

He was behind his desk, leaning towards her. Arms on the table, sleeves rolled up enough to show forearms corded with muscle and flecked with dark hair. Not at all what she expected from a therapist. He looked more like someone who spent their working day with a shovel in his hands. Before she’d seen the photograph on his website, she’d imagined someone older, a sun-mottled pate with whispers of white hair, perhaps in a cardigan with spectacles hanging around his neck on a silver chain.

He was talking; offering her something.

‘Sorry?’ She felt her face heat. God, she was such an idiot.

‘Or I can make you a tea or a coffee?’

‘Nothing, thanks,’ she said. Drinking something would only delay the inevitable. She was here to talk, and now that she was seated, in this space, she wanted to get on with it.

Crossing her arms and her legs, she sent him a smile of apology. Perhaps she should have a drink. He looked disappointed that she’d said no. But she shook her head. Jesus, stop second-guessing everything.

Jenna watched wordlessly as Luke opened a folder on his desk and picked up a pen.

‘I just need to ask you some basic questions for my records,’ he said. ‘This is the only formal part of the process.’ He smiled and brandished his pen. ‘Name, address, occupation, etc. And a short medical history, if that’s okay.’

She nodded her assent, and they began.

Chapter 3

‘Can you remember what was going on in your life when the anxiety first started?’ Luke asked after he’d completed the admin part of the session.

As he waited for her to answer he discretely looked her over, searching for clues to her life. We all wear a disguise, or in this case a hat, but often that attempt at camouflage gives away more than we intend.

Luke had been around a fair few gyms in his time and it looked like this young woman was no stranger to them either. She was all in black: leggings, T-shirt, gilet and baseball cap, her black hair in a ponytail, pulled through the hole in the back.

‘My last boyfriend left me…’ She coughed. ‘For another man.’ She laughed and shook her head. ‘When it’s another woman and you still want him, there’s a chance you can compete. Or you kid yourself you can. Lose a few pounds, get a new haircut, you know, all those surface, shallow things? But it’s never about you, not really. That stuff is just grasping at straws. We know that.’ She said the word ‘we’ as if speaking for her female peers. Then she stopped – as if she was afraid she was rambling.

Luke motioned to her to continue.

‘We can’t stop ourselves from making that effort, eh? So much of what we read and see is about projecting the perfect image. How to get yourself a man, and once you’ve got him, how to be a good wife. All that shite.’ She tossed her head as if mimicking a perfect-ten model in an ad campaign, and Luke found himself warming to her self-deprecation, to the glimmer of attitude that showed she was a fighter.

‘But when your competition’s a man?’ Jenna continued. ‘You can’t suddenly grow the right body part, can you?’ She paused as she gathered her thoughts. ‘Is that offer of a drink still on?’ she asked.

Luke got to his feet and stepped across to the drinks corner, asking her what she wanted as he did so.

‘Water will do, thanks.’

He retrieved a drink for her and held it out. She took it with a small smile of thanks.

She sipped.

Luke moved back round to his chair, and as he sat it occurred to him that this might not have been the first time Jenna had been let down by love. And while she appeared to be upset about this particular situation, he couldn’t help but feel there was something else going on. He’d only been working as a therapist for eighteen months, but he’d quickly learned that more often than not the problem the client initially presented with wasn’t really the issue they needed help with.

But he couldn’t rush it or he might lose her. He’d have to trust that by providing a non-judgemental ear she’d come to trust him and really open up.

‘And there’s my mum,’ Jenna said after a long silence.

‘Yeah?’

‘We have a woman who comes in, but I’m her main carer. She was such a vibrant woman. Full of vim. The life of the party.’ She paused, her expression lapsing into candour. ‘Actually, she was a judgemental pain in my arse. All that money she spent on my education, and I end up working part-time in a bookshop. What a let-down. But she was also very kind. Very caring.’ She stopped talking as a wobble appeared on her lower lip. Her head fell and her shoulders shook. ‘She was there for me when I really needed her. And now it’s my turn to look after her, and it’s just so hard.’

Luke retrieved a box of tissues from the shelf behind him and pushed it across the table top. Wordlessly, Jenna helped herself to one and dabbed at her eyes.

‘God, you must think I’m a horrible bitch. My mother’s had a bleed on the brain, and all I can do is complain about how she’s making my life difficult.’

‘You can still be a caring person while struggling with your obligations,’ Luke replied.

‘Yeah, well, that’s a nice thing to say, but it doesn’t make me feel any less of a cow.’

‘When you started talking about your mother, you talked about her in the past tense.’

‘I did?’ Her eyes were large with surprise.

Luke nodded.

Jenna looked away, and bit her lower lip, as if considering Luke’s statement.

‘There’s just this old version of her and the new, post-injury version.’ Jenna tugged at her left earlobe. ‘She’s very much alive.’ She looked into Luke’s eyes. ‘But, God she’s hard work. Used to be she’d rather die than be heard swearing. Now she swears like a navvy.’

Luke realised that allowing Jenna to remain stuck on the track of her perceived failings wasn’t going to help her. So he thought back to her first answer – when she’d responded to his question about when her anxiety started. She’d paused before answering, the movement of her eyes suggesting that shadows were chasing her thoughts. Then she’d arranged her features into a non-committal expression.

There was more here. He had to decide whether to press for it now or to let it unfold over the next few weeks of her therapy.

Instinct had him bin the cautious approach and press on.

‘Can you tell me the very first time you felt this level of anxiety?’ he asked.

She looked up at him, startled, as if worried he’d read her mind.

Eventually she broke her silence.

‘It happened a long time ago.’ Her eyes were heavy with shame and self-recrimination. ‘Someone died.’

Chapter 4

Part of him – the distant part – knew what he was doing when he tried so very hard to please them. But he still couldn’t stop himself.

Look at me, am I not a good boy?

Watch while I play with other children and demonstrate that I’m a credit to you both.

Listen while the teachers praise me for my hard work and attention.

What he was doing was really not that much different from the other kids. Putting on a performance to please the grown-ups, then, when out of sight and earshot, behaving in ways that demonstrated a conscience was yet to develop.

And while the compliant part of him did what he could to win smiles from the adults, the distant part watched on, like a cat curled up in the corner, with its tail over its nose, one eye open.

Waiting for just the right moment.

And the right target.

Chapter 5

Jenna sat back, crossed her arms and her legs. She was aware that the therapist would read this as a defensive gesture. And he would be right, but she was already regretting being quite so open.

‘Listen,’ she said, ‘I really don’t want to talk about that.’ She pulled her baseball cap from her head and hooked it over her knee. It fell off, and feeling her face redden she bent forward to pick it up.

Luke just sat there. Watching. His head cocked to the side.

She rushed to fill the silence.

‘I mean. It was horrible, you know, but it has nothing to do with what’s happening now. Really.’ Without thinking about what she was doing she uncrossed her legs and then recrossed them the other way. ‘And besides, we’d finished. I chucked him actually. The relationship just wasn’t working anymore.’

But at the start there was something wildly exciting about him. She couldn’t put her finger on it, but the minute, no, the second she saw him she was fascinated by him.

She was volunteering at a Christmas dinner for homeless people at her local church. He was picking up an old friend, she later found out, but when he saw her he pretended he was also one of the volunteers.

A dusting of beard, blond hair slicked back, his gaze bright with what she judged to be a street-wise intelligence. ‘Come here often?’ he asked, the glint in his eye sprinkling his opening gambit with a suitable amount of irony.

She couldn’t help but laugh, and he stood beside her, picked up a serving spoon and began to dole out the roast potatoes. As they served the men and women in the queue their conversation adopted an easy rhythm, ranging from all the things they loved and hated about the time of year, favourite movies, and, strangely, the stand-up comics that irritated them.

By the time he’d finished pouring cream over the Christmas puddings she was handing out, she suspected she was in love.

He was the first mature man to pay her any attention; previous boyfriends were just little boys by comparison. And he was everything her father wasn’t. Dad was an accountant, overweight, rarely seen without a perfectly knotted tie and never heard using what he called ‘inappropriate language’. This guy was as lean as an elite marathon runner, wore faded jeans and T-shirt, and peppered his sentences with ‘fuck’.

Years later she would mock herself for the attraction. They say the path to hell is paved with good intentions, she’d told a friend. I’m thinking those intentions are mostly from women who want to change their man.

There was nothing he did that day, or on most of their subsequent days together, that suggested he was a bad boy, but there was an edge to him, a suggestion that he didn’t much care what people thought of him. It was a world away from the ‘mind your Ps and Qs’ drill she’d heard almost every day growing up with her parents, and she therefore found it deeply attractive.

She was brought up to be a middle-class nice girl, always ready to smile, ready to acquiesce, never to make a fuss, and she was deeply tired of it. This was her chance to rebel. He was her chance to earn a disapproving word from her parents. To show them she was her own woman, not their little girl. And she grabbed it with both hands.

Her mind drifted to the end days. He became exhausting. Loud, with enough energy for six people. Then quiet and withdrawn for days. And utterly dependant on her for his happiness, or so it felt. She remembered that last day they were together. His eyes empty in the moment before he saw her, then, when he was aware she was there, he lit up as if he’d received a charge of energy. It was suffocating. It felt like he was relying on her presence to keep him together.

‘I can’t be without you,’ he said, slumped back into the sofa.

‘But we’ve been together less than a year.’

‘Eleven months, one week and three days,’ he said with a little flare of triumph in his eyes. ‘Which is a guess.’ His smile was straining with hope that his little joke landed well in her mind. ‘Some people get married after knowing each other for a day.’ He was pulling at her hand, his eyes beseeching.

She reared back at the word ‘married’.

‘It’s too much,’ she said, every inch of her wanting to be far from him. ‘You’re too much.’ As she spoke, her eyes flashed to the bin in the corner of the kitchen, where she’d thrown the used pregnancy test. Its little blue lines like neon in her brain.

‘What the fuck does that mean?’ He was back on his feet, and it looked like the clench of his fists was lengthening his arms. Not for a moment did she feel threatened by him; her worry was that he would harm himself. Slam his knuckles into a wall, or a window or something. Or worse, take it out on someone else. When they’d first got together she’d heard the talk about his capacity for violence, but when he turned out to be a sweet, vulnerable guy, she was sure those rumours must be about a different person. There was no way the guy who cuddled up to her, the guy who cried at soppy adverts, was the one these people were talking about. It was ridiculous.

‘I’m not what you need. Can’t you see that?’ She hadn’t told him about the baby yet and was dreading having to do so.

‘Everyone else has fucked off. You can’t leave me too,’ he shouted. Who the everyone else were he never actually said. He rarely mentioned family, saying he missed his little brother but couldn’t take the shit he’d get from his parents if he went to see the wee fella. He did once talk about a guy. His oldest friend. They’d had a massive falling out, and it was clear that whenever he was down, which was often, this still bothered him greatly. But when she pressed him on it, he clammed up, as he did about every other part of his life.

‘We used to be out all the time. You were the life and soul of every party, but now we’re here every night…’ She looked round his living room. The vanilla-coloured woodchip on the walls, the three-bar electric fire from another era, the curtainless windows. ‘…While you drink vodka and smoke hash.’

‘But nothing else matters. Just me and you, babe.’ His eyes searched hers for agreement. ‘We’ve been good together, yeah?’

‘Yeah. But…’ The ‘yeah’ referred to the early months of their time together. He was her first real boyfriend. He seemed so worldly and solid. And he took her places for posh meals and weekends away. The trip to London to see Beyoncé in concert was a real highlight. It was continuous excitement, and she’d felt so, so lucky. Chosen, almost. And it was a huge difference to the world she inhabited before.

‘Me and you. Against all the bastards out there.’

‘That’s the problem though, eh?’ she tried to argue. ‘Your “them and us” way of thinking. You haven’t even had me over to meet your family. That’s just weird.’

‘You know how I feel about my family.’ His face darkened.

‘I don’t. Not really. You barely talk about them.’

The therapist shifted in his seat, pulling her from the quicksand of her memory.

‘We had a massive falling out.’ She cleared her throat, the remembered guilt gnawing at her vocal chords. ‘I did what I had to do. There was no real choice. He was…’ She thrust out her chin and chased emotion through her mind, searching for the right word. ‘Damaged. Seems horrible to write anyone off, but I always had the sense he would die young, you know?’

She sipped from her water, suddenly aware of how dry her mouth was.

‘I was twenty-one when I met him. You think you know everything at that age, don’t you? But I knew nothing.’ Her laugh was self-mocking. ‘Young and daft. Attracted to certain men for all the wrong reasons.’

Silence followed. Jenna sought a way to change the subject. She looked at the clock on the wall. There were fifteen minutes left? Heat was building in her chest and neck. She pulled at her top. God, she just wanted to leave. She shouldn’t have come.

‘And you’re probably thinking that’s why I’m so bothered about being there for Mum? That I wasn’t there for my old boyfriend?’

‘You think it’s some sort of displacement?’

‘I’m not saying I think that. I’m saying you’ll think…’ Aware she sounded short, she got to her feet. ‘Sorry, I need to go.’ Her fingers were tingling. It was too hot in here. Her lungs were scratchy, she couldn’t breathe. ‘I’ll go onto your website and book another…’

Seconds later she was out of the door and walking back up the garden path, her past like an anchor behind her, the weight of it gouging into the earth. Her thighs trembling with the effort of pulling. It was so much a part of her she no longer registered exactly how much work it took.

Chapter 6

Luke was listening to a young woman in her late twenties, the folds of her barely contained by the spacious armchair she was sitting in. Her face was florid, and a bead of sweat was cresting her hairline, about to spill onto her forehead.

‘I lost over a hundred pounds five years ago. I was on the shakes an’ that,’ she said. ‘Minute I stop: boom. The weight goes back on.’ She started crying. Luke leaned forward and held out a paper handkerchief. ‘I’m just so tired of it, you know?’

‘Exactly what are you tired of…?’ He sought her name in his mind. Looked at the papers in front of him. ‘Susan.’ That was close. He’d almost called her Jenna. Ever since Jenna had left his office he hadn’t been able to stop thinking about her. He’d worried he wouldn’t see her as a client ever again. It was in the hang of her head and her studied steps as she walked away from him up the garden and round the side of the house.

The information she’d given him included her job as a part-time bookshop assistant. And there was only one little bookshop in the area. He’d found himself walking past the door several times over the last few weeks. But he hadn’t gone in. The client-therapist line was something he wouldn’t – couldn’t – cross. But there was something about her. Something familiar. Something engaging. There was a vulnerability there. And a strength he suspected she didn’t know she had. And when she smiled, he felt himself react, trying to find other things to say that might winkle another smile out of her.

She was a pretty girl. Very pretty. Reminded him of Lisa, if he was being honest. She had the same large eyes and full lower lip, but where Lisa’s hair was auburn, Jenna had a mass of dark-brown, shoulder-length curls.

Whenever the phone rang he would take a moment before looking at the screen, not wanting to be disappointed when he saw it wasn’t her. Every new ping of an email gave him a little frisson of pleasure. Just in case.

A few days earlier he’d spotted her in the supermarket, over at the fish counter. He allowed himself the imagined treat of going over and saying hello. Savoured her imagined smile in response. But of course he didn’t. His personal rule when he was out and about was only to respond to clients if they said hello first. He would never initiate contact, in case they didn’t want whoever they were with to later question who he was.

Luke brought his attention back to Susan, feeling bad that he’d been so easily distracted. She was talking about the stares of strangers, the looks she got whenever she ate anything out in public.

‘You can eat a slice of cake, or a packet of crisps or whatever, outside on a bench in the park, and no one will blink an eye. People see me eat and the judgement just pours off them. It could be the only thing I’ve eaten that day, cos I’m on a ridiculous diet, but still they judge.’ She shook her head and dabbed at her eyes with the paper hanky. ‘They even shout stuff at me. Make grunting pig noises.’

Susan had booked in for a hypnotic gastric-band session. It was obviously way less invasive than an actual gastric band, she’d said, and if she could be convinced she had a tiny, tiny stomach, that would be totally fab.

‘Not that I want to turn away the business,’ Luke said. ‘But we’re not that far away from Christmas. Do you want to be going through this with all of that added temptation? Sweet treats everywhere you go?’

‘I don’t go anywhere,’ she said, her face limp with sadness at her admission. ‘Besides, no time like the present, eh?’

Luke nodded his understanding, paused, took some notes, and then prepared to give Susan first some words of support, and then a hard slice of truth.

‘Your struggle with weight is not an indication of a fault in your character, so please push that belief right out of your head,’ he said softly.

She looked him in the eyes. ‘I know, right?’ Her own eyes were hooded with a contradictory doubt.

‘You’re not a bad person, Susan. This is a massively complicated issue. Do other members of your family struggle with this?’

She nodded. ‘Mum’s side are all pretty big.’

‘Right, so genetics play a part. Also, there are a number of hormones involved in the weight-gain process. If you’ve been eating the wrong things for you over a long period of time, your hormones may be out of whack. Then there’s the emotional side of it. Do you turn to food for support?’

Susan offered a little smile.

‘And you try to apply some logic to that? Give yourself a talking to?’

Another smile of recognition.

‘And how’s that working for you?’

‘It’s not.’

‘These kind of patterns of behaviour are imprinted deeply in our brains. Applying logic to something that is illogical is … illogical.’

Susan laughed.

‘And, something else people don’t take account of is how the processes that lots of our foods go through is designed to hijack our brains to make us eat more and more and more.’

‘It is?’

‘Absolutely. Our body is designed so that we stop eating when we’re full, but these processed foods switch off that feeling of satiety. Ever wondered why one Hobnob is never enough?’

‘God, I love Hobnobs.’

Susan’s body language had changed over the last five minutes; her chin was up, her shoulders back, both feet planted, and her eyes were bright with interest.

‘And there was even one piece of research where a woman’s body type changed after she had a stool transplant.’

‘You what?’ Susan grimaced.

‘Don’t know why Hobnobs made me think of that,’ Luke joked. ‘But from that experiment it’s clear that the micro-organisms in our gut also have an impact.’

‘So how do I fix that?’

‘Great question. And that’s where the long-term solution to your problem is; but first you have to believe me when I say this is not a character fault. Again, you are not a bad person, Susan.’

‘Okay,’ she said in a small voice, as if she was preparing to accept that idea. She dabbed at her eyes again.

‘I’ll do the gastric-band stuff, if that’s what you want. But…’ her face fell at the ‘but’, so he rushed to reassure her ‘…there’s something deeper here. We should try to uncover why you overeat – the emotional component that drives you to food – and deal with that first, or I’m doing you a disservice.’

Susan sighed.

‘Trust me, Susan, the gastric band on its own will possibly only be one part of the overall solution. If you want to deal with the habit of turning to food for emotional support, there’s some work ahead.’ He leaned forward and touched the back of her hand. ‘But I’ll be here with you every step of the way. Okay?’

*

Once Susan had left he typed up her case notes and checked his diary. That was him for the day. He looked at his phone. 2pm. The wee fella would be home from school soon. Time enough for a quick visit to a certain bookshop? He did actually want to buy a book. A highly regarded work on trauma called The Body Keeps the Score.

Some minutes later, having finally managed to find a parking space, he walked past the shop window, feeling very self-conscious as he did so, pushed the door open and entered.

Chapter 7

They allowed the boy to live with them until his eighteenth birthday. Wasn’t that kind of them? they asked. Besides, they said, no one else was rushing to look after him. Even his own sister didn’t want anything to do with him, the woman added with a self-satisfied smile.

He could only nod while looking down at the small suitcase at his feet. It contained every last one of his possessions, and still had room to spare.

‘I have to leave?’ he asked.

‘Time to stand on your own two feet,’ the man said.

‘The charity we told you about will make sure you’re okay,’ the woman said. They were holding hands, standing in front of him like a twin barrier. Matching expressions. Eyes empty of care.

He took a step towards them. Just a small one.

In unison they backed away.

The part of him that had watched and waited all these years felt the thrill of their reaction. He caused them worry. They were actually a little afraid of him.

Good.

But the part of him that had obeyed all these years shrank. He could feel his lower lip trembling. He was being discarded. They’d thrown out an old sofa the previous week with about as much emotion.

They’d taken him round to his new place a few weeks back. A large house split into what amounted to bed-sits. Space enough for a bed, a table, and a kitchen small enough to fit into a walk-in cupboard.

The windows were all barred. The doors were as heavy as if they were armour-plated.

‘Well, isn’t this cosy,’ the woman had said, the momentarily startled look in her eyes giving the lie to her statement.

He would have his independence there, he tried to tell himself.

But still, even though the couple had treated him harshly, their attention was all he knew.

There had been good times, once. Long before the couple.

But he barely remembered them.

A mum and a dad.

They were always fighting and drinking, and calling him nasty names, but still. They were his mum and dad. Then there was a big sister and bigger brother. Watching cartoons. Plates heaped with beans and toast, and eggy bread. And chips. And the occasional glass of Coke.

Then his big brother died.

Whispers swarmed around his head. Conversations ran into the brick wall of him entering a room. His sister was no help. She pretended to be in the know, but knew as little as he did.

His mother wore the same set of clothes for months, arms permanently crossed over her black cardigan as if that might contain the grief.

Desperate for information, for any detail at all, he began to creep around the house, pausing at doorways for long moments before entering, sure that he’d catch some snippet of information.

Then his father got lost in the bottle. Many, many bottles. Killed his mother and himself, in a twisted echo of his eldest son’s passing: drunk driving on the way to Danny’s graveside on the anniversary of his death.

That was then.

Now was more important.

His foster parents turned to leave. No hugs. They didn’t do contact. Of any kind.

No encouraging words.

But he had silent words for them.

Sleep well tonight, he thought. But sleep with one eye open.

Chapter 8

Jenna had been surprised at herself after her therapy appointment. She hadn’t talked about that part of her past for ages. A memory of him popped up in her mind. Unshaven, wearing a T-shirt and boxers. Looking tired. He always looked tired towards the end. As if he’d given up. Yet when they first met he was always immaculately turned out: neat beard, expensive clothes, and shoes with a shine so deep you could use them as a mirror. And he was always the most vibrant person in the room. He was the sun around whom everyone else would orbit, hoping for a word, a nod, a smile.

She cursed herself for being an unfeeling bitch and not looking after him better. Could there really have been any other outcome? It was his fun and energy that drove her to him. When had he changed? She rubbed at the memory a little more and felt some of the emotion of that time leak into the present. She held a hand to her stomach, and a tear wound its way down her cheek.

He died just a few days after they’d split up, and she’d been tempted to use her old skills as a local journalist to find out exactly what happened. She’d done some digging and took some notes. Then, when her father died of a sudden heart attack soon after, she put the notebook away in a box somewhere and consigned that episode of her life to history. Besides, the system was happy, the people concerned were punished, and that should be the end of it. Right?

Within minutes of her appointment ending, Jemma’s phone had rung. Hazel, of course calling to find out how her session had gone.

‘Did he do any of that hypnosis malarkey with you?’ she had asked, as if both thrilled and terrified at the prospect of experiencing such a thing herself. At times they spoke almost every day, she and Hazel. Then they’d have long silences. They’d been at university together, lost touch, and reconnected on-line a few years ago. But they only ever chatted to each over the phone or by messaging. Her other friends thought it strange that they never met in person, but Jenna was happy with the relationship as it was. It just sort of worked. It suited how they were with each other. Nothing was off the table, and Jenna worried that if they did meet in person they would lose some of that magic.

‘It wasn’t like that,’ she replied. ‘We just … talked.’

‘Is he hot?’ Hazel asked. ‘He looks hot in his website photo.’

Jenna laughed. ‘What are you like?’ She paused. ‘To be honest, I felt uncomfortable. I wanted to trust him. Tell him everything, you know? But something held me back.’

‘You’ll know when you’re ready,’ Hazel said. ‘And you know you’ve got me, babe. Anything you want to offload, I’m here for you.’

‘Thanks, Haze,’ Jenna replied. ‘I appreciate it.’ As she spoke she thought about the things she had always shied away from talking about. She couldn’t bear the thought of anyone knowing about that; facing the judgement in their eyes. Could she go back and discuss all that with him?

No, that was a cross she’d have to bear on her own.

Jenna’s thoughts were interrupted by the chime above the door telling her someone had entered the shop. Her only customer so far that morning had been one of her regulars, Mrs MacPherson.

‘It’s got a girl with a red coat on the cover,’ Mrs MacPherson had asserted. She was a lovely old soul. Never left her house without her trolley-bag and a blue rinse. Bought loads of books, but often set her these interesting challenges. It was good training for dealing with her mother.

‘Oh,’ she said when she turned and saw who her next customer was.

‘I’m looking for a book.’

‘You’re in the right place.’

Luke smiled. ‘It’s by Bessel Van Der Kolk.’

She couldn’t help herself. A giggle bubbled up. ‘That’s an interesting name,’ she said. Then she squirmed a little. Feeling bad that she hadn’t been back to see him. ‘I’m guessing he’s not from Airdrie,’ she added.

‘I think that would be a good guess.’

He had a nice smile. It took years off him.

‘Let me, eh…’ she turned to the computer ‘…check.’ She felt her face heat.

Wait a minute – was she attracted to this guy?

‘It’s called The Body Knows the Score.’

‘And I’m guessing that’s not a reference to the latest Rangers versus Celtic match?’ She instantly regretted her attempt at humour.

He laughed. She stared at the screen. It really hadn’t been that funny.

The door chimed, and a woman in a blue coat came in. This was Mrs Docherty. She’d ordered the latest Martina Cole, and it had just come in that morning.

‘Do you mind if I…’ she said to Luke.

‘Not at all,’ he said, and stepped to the side.

Mrs Docherty took a long second to give Luke the once-over before she bustled up to the counter.

‘Is it in, hen?’ she asked.

‘Just arrived this morning,’ Jenna answered, reached under the counter to the pile of arrivals and picked out Mrs Docherty’s book. She put it in a bag, along with a couple of bookmarks and rang the cost up on the till.

Mrs Docherty paid, took the book and put it in her bag. Before she turned to leave she leaned forward, tilted her head towards Luke and in a stage whisper said, ‘Good choice, hen.’

Then, as if she’d approved the love match of the year, she sashayed out of the shop.

‘You must get a lot of characters in here,’ Luke said.

‘You don’t know the half of it.’ Jenna smiled. Before working in the shop she’d seen reading as a solitary pastime, but working here had shown her that readers were a community of the best kind of people, and now she couldn’t imagine working in any other kind of place, in spite of her mother’s chagrin.

In guilty moments she’d prayed that the change of personality in her mother following her head injury would result in a less judgemental side emerging. But she couldn’t have been more wrong.

‘What a waste,’ her mother had said that morning when she called in to check on her. ‘Waste of an expensive education. We put you through private school and for what? For you to work in a bookshop? What about that journalism degree, eh?’ If her mother had ever held back her opinions she was now free to say exactly what she felt. All filters removed by what the doctor likened to a storm going off in her brain.

‘Yes, Mum,’ Jenna said while checking the cupboards to make sure there was enough food in the house. ‘And for the millionth time, I didn’t throw it away. I was made redundant. People don’t pay for news so much nowadays, and the bookshop was the only place that would have me.’ There was a hugely capable woman called Martie who came in daily to make sure her mum was clean and dressed and fed, and Jenna was happy to let Martie do her job, but she needed to salve her conscience by coming in every day to check. Which sadly also meant her running the gauntlet of her mother’s insults and accusations.

‘I suppose you’ve taken up with another druggie arsehole. Just don’t be thinking he’s going to get any of my money. It’s all under lock and key, m’dear.’

That was one of the more recent tirades, and no matter how many times Jenna told her she was done with men, her mother kept at it.

While Jenna opened her computer and accessed the ordering system, Luke wandered off to look at the bookshelves. Jenna was always interested in what other people liked to read, so she watched as he scanned the fiction section before landing on the self-help books.

To be fair that was relevant for his job. Maybe that was all he read?

The book he’d asked about popped up on her screen. ‘It’s in stock at the warehouse,’ she called over to him. ‘Would be here in a couple of days. Are you happy for me to order it?’

‘Yes, please,’ he replied.

‘Excellent,’ she said. It meant she would get to see him again.

But there was the issue of him being her one-time therapist. She wasn’t going back, so it really was a one-time deal, even though a quiet voice asserted she still needed the help.

She pressed the button to order the book, and asked for his name and address in a reverse echo of their first meeting.

‘That’s your book ordered, Mr Forrest,’ she said.

He smiled his thanks and said, ‘See you in a couple of days.’

Disappointed he hadn’t lingered a little while longer, Jenna watched as he walked towards the door.

As he opened it a young man stepped inside and paused.

Not him again, she thought. He’d been hanging around for weeks. Seemed harmless at first, but now he was giving her the creeps. He’d begun by walking past the big shop-front window and stealing glances inside. Then he graduated to standing over at the crime section, casting glances her way before leaving empty-handed.

It was Mhairi, the shop owner, who first spotted him.

‘I think you’ve got a fan,’ she’d said a few days earlier.

‘Nonsense,’ she replied.

‘Yup.’ Mhairi nudged her, grinning. ‘It’s only on the days you’re working that he does his walk past. He even went so far as coming in the other day. When he realised you were off he actually ordered a book.’

‘Why would he do that?’

‘So he could come back?’

Jenna shivered. ‘That’s creepy.’

‘Ocht, he’s harmless. Look at him, he’s barely started shaving.’

She heard the young man apologise. Then there was a pause before Luke spoke in a tone it was difficult to analyse. Equal parts pain and pleasure.

‘It can’t be,’ Luke said. ‘God, you’re his spit. Jamie? Wee Jamie? I used to run about with your big brother. Man, you’re his spitting image.’

Chapter 9

Recognising that he was feeling an attraction to his one-time client, while trying to play it cool and professional, Luke felt his cheeks flush as he pulled open the door. He was so distracted he almost wiped out the young man who was trying to enter as he exited.

He looked up at the guy, saw an expensive wool coat, faint stubble on a sharp chin and a short haircut. But then he stopped as if he’d walked into a wall.

The eyes, the nose, the colouring of both his skin and hair, and it was like time had reeled him back to another era. To another young man. The resemblance was uncanny.

‘Jamie? Wee Jamie Morrison? God, you’re his spit.’

‘Sorry?’

‘I should apologise,’ Luke said, hand over his heart. ‘I only saw you the once, as a kid. Your brother had to bring you along with him this one time.’

‘You knew my big brother?’ the lad asked.

‘We … eh … grew up together,’ Luke replied.

‘He died, you know,’ Jamie said. ‘Long time ago now.’

Just then an elderly man approached the door and made as if he was trying to get in.

‘Ah’ve seen everything now,’ the old man said with a wink that included them both. ‘Bouncers on the door o’ a bookshop.’

‘Sorry,’ Luke said, wondering if the old man had come across him doing his other job: doorman at the local pubs and clubs. He aimed a wave to the desk at the back of the shop. ‘Thanks, eh … miss. I’ll come and collect my book in a couple of days.’

He stepped to the side, indicating to Jamie that he should too.

‘How the hell are you? God, you were only a wee mite when I saw you last. But, man, that face. You’re a Morrison and no mistake.’

‘Yeah, well,’ Jamie said, and crossed his arms. He looked away and then back. ‘I only have a few memories and some tatty photos to compare.’

Luke examined the young man and, thinking through the years, guessed that he would be in his mid-twenties. A kaleidoscope of memories pushed through his mind. Some good, some he wouldn’t want to look at unless he was sedated with whisky, or in the presence of a good therapist.

He could feel his pulse hammer in his throat and his mouth dry.

Would the guilt ever leave him?

‘Listen, it’s great to see you, man,’ he said as he began to turn, thinking now that he had to get away.

‘Hey, man,’ Jamie said. ‘I know next to nothing about Danny. I was so small when he died, but in some ways he was so big in my imagination.’ Jamie looked into his eyes, and there was a please framed there. ‘It would be great to talk to someone who actually knew him. You got time for a coffee? You can tell me all about the good old days.’

The good old days.

Little about those days was good, thought Luke.

‘Sorry, mate. Another time, eh? I’ve got to go and pick up my wee man from school.’

‘Ah, okay,’ Jamie said as he stuffed his hands into his pockets, and Luke felt a charge of guilt. Whatever his big brother’s sins were he shouldn’t judge the younger man by the same measure. Besides, in spite of all the therapy he’d undergone he was still to examine those times properly. Perhaps a chat would prove helpful to them both.

‘Listen…’ He fished out his wallet, pulled out a business card and handed it to Jamie. ‘Here’s my number. Give me a call and we can arrange to meet up sometime.’

Jamie looked from the card to Luke. ‘The Therapy Shed? That’s you?’

‘Yeah,’ Luke replied, his tone a request for clarification.

Jamie waved the card in front of him. ‘This is weird. I’ve got an appointment with you next week.’

Chapter 10

After Luke had fed Nathan, played on the Xbox with him and got him ready for bed, he pulled out his laptop to check his online diary.

‘Daaaad,’ Nathan shouted down from his room the moment Luke settled on the sofa. ‘It’s too dark.’

He’d never stop loving hear Nathan calling him ‘Dad’, but a wee break to get on with his work would be great.