10,80 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Prospect Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Quinces have become an undeservedly forgotten fruit. This book reintroduces them, making them more accessible and providing an inviting range of recipes. The trees do not require much space, and are easy to grow. The fruits are delicious and versatile and the recipes here extend well beyond jellies and jams, including sweets. From Goat's Cheese Tart to Quince Chocolates and Liqueurs, there is something for everyone. The quince has always had a special place among the fruits of Europe. The ancient Greeks called it the 'golden apple', the Romans the 'honey apple'. And it was most likely a quince, not an apple, that Eve plucked from the tree in the Garden of Eden. This book describes both the cultivation, the history and the cooking of quinces. There is a sketch of the glorious history of the fruit in cookery of past ages; there are some excellent recipes for savoury dishes that depend on the quince for that special flavour, and for all those sweet dishes that bring out the unique qualities of the fruit.We tend to forget that the first marmalades were made from quinces.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

THE ENGLISH KITCHEN

QUINCES

GROWING AND COOKING

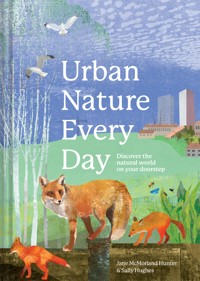

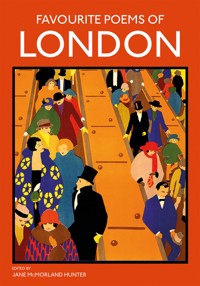

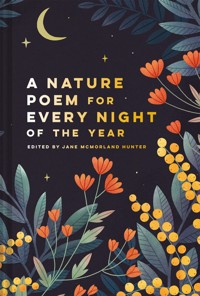

JANE MCMORLAND HUNTERAND SUE DUNSTER

To

Bill, Sophie and Rose

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Out of season quinces are impossible to obtain and even in season they are usually only available at the more inspired farmers’ markets and a few selective shops. This seems a sorry state of affairs for a fruit which is delicious in both sweet and savoury dishes, can easily be preserved and will enhance a room with an unmistakable yet delicate fragrance.

The easy solution is to grow your own quinces and the purpose of this book is to encourage everyone to do exactly that. Quinces grow on attractive trees which never become unmanageably large and will improve any garden. They can even be grown in containers. In late spring the trees are covered with the most exquisite, fragrant blossom. This ranges from white to pale pink and is set against a backdrop of furry grey-green leaves. The blossom does not last long, but while it is in flower there is little that can rival it. The trees themselves grow in a twisty, slightly mad, but attractive manner, although some varieties can be trained against a wall in an espalier or fan. The fruit appears in late summer and ripens towards the end of autumn. In northern Europe the fruit never ripens sufficiently to be eaten raw, but is so delicious once cooked that this really does not matter. The trees are highly productive and fairly unfussy as to where they grow, in particular, the cultivar ‘Meech’s Prolific’ certainly lives up to its name. The trees self-pollinate which means you only need one to get fruit. They are largely disease-free, fruit reliably most years and will live to a great age, enhancing your garden and providing you with a scrumptious crop in return for little input.

Quinces were reputed to be the fruit which Paris gave Aphrodite and it was said that quince trees grew up wherever she walked. They may have been the infamous fruits on the Tree of Wisdom in the Garden of Eden. Much later Edward Lear’s Owl and Pussy-cat dined on them at their wedding feast. They originally came to Europe from central Asia where they still grow wild in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains in Turkmenistan and Iran. They have been used in Persian cooking for over 2,500 years, but probably reached Britain in the thirteenth century where they appear in recipes for pies sweetened with honey.

Quinces are deliciously sweet and scented when cooked. They contain a high level of pectin and can therefore easily be made into jams and jellies. Originally marmalade was made from quinces coming from the Portuguese word for the fruit, marmelo. A little goes a long way and the addition of a few slices will transform sweet and savoury dishes. They combine particularly well with apples and pears, but will also go with almonds, oranges and even mulberries, if you can get them. They can be made into cakes, tarts, biscuits and custards. They are used in many Mediterranean and central Asian savoury dishes including chicken, pork and all types of game. They can be stuffed with meat and used to flavour savoury tarts. There is so much more to them than just the jelly and membrillo commonly found in delicatessens.

Even before you cook with them quinces can be used to scent a room. Once ripened, they are an attractive golden colour and will keep in a bowl giving off a delightful fragrance.

The first part of this book gives a brief history of quinces to put them into context in both the kitchen and the garden. A section on growing quince trees follows which gives all the information you need to select and care for a suitable cultivar. The final part covers storing, cooking and using the fruit, in both modern and historic recipes. Do not be put off by the fact that they usually need to be cooked, so do lots of other ingredients and the rewards for cooking quinces are enormous.

THE STORY OF THE QUINCE

The earliest known quinces grew wild in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains between Persia and Turkmenistan. This seemingly inhospitable area is actually very fertile and many fruits thrived. A knobbly, irregular-shaped variety still grows wild in this area. The valleys below formed many of the ancient trade routes and quinces spread rapidly westwards and eastwards. To the west they were carried along the old trade routes, reaching the Middle East and then the Mediterranean as Golden Apples, flourishing as they went. To the east they were taken across the deserts of the Silk Road and thence to China where they arrived as the Golden Peaches of Samarkand.

They quickly became very popular and were credited with both mythical and medicinal powers. From ancient times right up to the late Middle Ages quinces were, in most places, more widely used and better known than apples. Related to both apples and pears, it is sometimes hard to identify quinces in classical literature, especially as the Greeks tended to use the term melon to refer to both apples and quinces, but it is likely that most golden apples mentioned were actually quinces as they would have been more widely cultivated and better known, particularly in the Levant and southern Europe. It is important to remember that the quinces of central Asia, the Middle East and south America can often be eaten straight from the tree. Quinces were also favoured because it is only comparatively recently that the people of the West have developed such a sweet tooth. Many other regions of the world still appreciate astringent flavours and historically these tastes would have been the norm as sweeteners other than honey were rare and expensive.

One of the quince’s earliest possible claims to fame is the Judgement of Paris in Greek mythology. Eris is the Greek goddess of strife and in a foolish miscalculation she was the only god not invited to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Understandably furious, she barged into the wedding ceremony and threw down a fruit inscribed ‘For the most beautiful.’ This fruit was described as a golden apple and was, almost certainly, a quince. Hera, Athene and Aphrodite each claimed the fruit, so Zeus decided that the matter should be settled by Paris. Hera offered him empire, Athene guaranteed military glory and Aphrodite promised him the most beautiful woman in the world. This was Helen, who was unfortunately already married to Menelaus of Sparta. Paris gave the fruit to Aphrodite and she in turn helped him win Helen, thereby sparking off the Trojan War. The main result of this episode for quinces is that ever after they have been regarded as Aphrodite’s fruit. They are associated with love and fertility and it was believed that the trees sprang up wherever she walked, alongside the better known flowers.

The quince’s link with Aphrodite ensured it an unofficial place in wedding ceremonies. In 594 BC Solon was elected chief magistrate of Athens. He was a politician, but also a poet and although he is described by George Forrest in The Oxford History of the Classical World as being ‘self-centred, self-righteous and just a trifle pompous’ he at least kept written records and concerned himself with more than simply amassing power. He tried to establish peace and democracy by writing a new law code and instituting social and political reforms. In due course he set down the format for wedding ceremonies and the quince’s part was officially recorded. From then on quinces have been part of the Greek wedding ceremony and are often baked in a cake with honey and sesame seeds. This is said to symbolize the couple’s enduring commitment to each other through good times and bad. The fruits are often thrown to the bride and groom as they go to their new home and the bride is presented with a quince to ensure fertility. One myth says that pregnant women who indulge their appetites in generous quantities of quince will give birth to industrious and highly intelligent children. Edward Lear was following an ancient precedent when he included quinces in the Owl and the Pussy-cat’s wedding feast.

The Owl and the Pussy-cat went to sea

In a beautiful pea-green boat,

They took some honey, and plenty of money,

Wrapped up in a five-pound note.

The Owl looked up to the stars above,

And sang to a small guitar,

‘O lovely Pussy! O Pussy my love,

What a beautiful Pussy you are

You are,

You are!

What a beautiful Pussy you are!’

Pussy said to the Owl ‘You elegant fowl!

How charmingly sweet you sing!

O let us be married! Too long we have tarried:

But what shall we do for a ring?’

They sailed away, for a year and a day

To the land where the Bong-tree grows

And there in a wood a Piggy-wig stood

With a ring at the end of his nose,

His nose,

His nose,

With a ring at the end of his nose.

‘Dear Pig, are you willing to sell for one shilling

Your ring?’ Said the Piggy ‘I will.’

So they took it away, and were married next day

By the Turkey who lives on the hill.

They dined on mince and slices of quince

Which they ate with a runcible spoon;

And hand in hand, on the edge of the sand,

They danced by the light of the moon,

The moon,

The moon,

They danced by the light of the moon.

(Edward Lear (1812–1888), Nonsense Verse)

Golden apples or quinces also feature in the myth of the twelve tasks of Heracles. As the eleventh task he had to fetch the fruit from the golden apple tree in Hera’s sacred garden on the slopes of Mount Atlas. The tree had been Mother Earth’s wedding gift to Hera and she had created her divine garden around it. Guarded by the dragon Ladon and surrounded by a high wall, scrumping from the garden was clearly a formidable task. Ladon was curled round the base of the tree and Heracles had to shoot him with an arrow, before persuading Atlas to fetch the fruit. This proved surprisingly easy, as Atlas was carrying the globe on his shoulders and Heracles offered to support it for him in return for the fruit. This was a popular tale for sculptors and artists and the scene of Heracles supporting the world while Atlas brings him the golden apples can be seen on a white-ground vase in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. On this vase the fruits do look remarkably knobbly, giving further support to the idea that they were actually quinces, rather than apples. There is also a splendid statue of Heracles in the British Museum in London, showing him standing in front of the tree with three golden apples in his hand. Again, the fruits could easily be quinces, rather than apples.

There are records of quinces being cultivated 5,000 years ago by the Mesopotamians and from 100 BC onwards they were popular in Palestine long before apples. It is quite likely that the fruit in both the Garden of Eden and the Song of Solomon were quinces rather than apples.

The Romans also cultivated quinces, particularly for their medicinal qualities. There is a terracotta quince in the British Museum which is over two thousand years old. It was made in Apulia in southern Italy between 300 and 250 BC and was obviously originally part of a collection as a pomegranate has also survived. The fruit is life size and you can really see the knobbliness. Cato, in his farming manual of 202 BC, On Agriculture, included a number of recipes and recommended growing three types of quince: Strutea, Cotonea and Mustea, a variety which ripened well. Pliny, a Roman naturalist in the first century AD, praised their medicinal virtues, claiming, among other things, that they warded off the evil eye. He mentions the Mulvan variety, which was the only cultivated quince at the time that could be eaten raw. Quinces also featured in The Satyricon, by Petronius. Written around 65 AD this was a huge work of which only a small part survives. It is an amusing literary portrait of Roman society at the time and follows the adventures of two scholars as they wander through the cities of the Mediterranean. In Rome they go to a dinner given by Trimalchio, a vulgar freedman who has considerably more money than style. The whole event becomes more and more tasteless, culminating with a dessert including ‘Quinces, with thorns implanted to make them look like sea urchins.’ It is not clear whether this dish is actually eaten, but quince dishes were obviously well known enough for Petronius to use them in his book. The Greeks and Romans preserved quinces in honey, giving rise to the name melimelum from the Greek for honey apple. In turn this evolved into the Spanish marmello and thence membrillo which is probably the best known use for quinces nowadays.