Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: NHB Modern Plays

- Sprache: Englisch

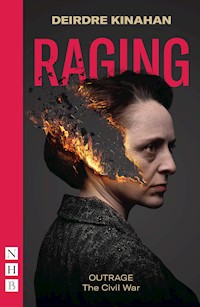

Part of Deirdre Kinahan's trilogy of landmark plays commemorating seven years of warfare in Ireland, Outrage explores the true nature of women's roles in the Irish revolutionary wars, and in particular the Civil War in 1922. Alice and Nell are sisters who play key roles in organising civic resistance and the propaganda war. They are fervent, they are funny, they are human and they – like everyone else in Ireland – become deeply conflicted as the country spins toward a shattering Civil War that splits the nation, and continues to haunt Irish politics, society and culture to this day. Outrage was first staged as a touring production by Fishamble: The New Play Company, in partnership with Dublin Port Company and Meath County Council, in 2022. Deirdre Kinahan's Raging trilogy tells powerful stories drawing on a tumultuous period of conflict in Irish history, from the 1916 Easter Rising to the Civil War which began in 1922. Each of the three plays – Wild Sky, Embargo and Outrage – was first performed a century after the event which it depicts, and they were commissioned and performed by companies including Fishamble: The New Play Company, Meath County Council Arts Office, Dublin Port Company and Iarnród Éireann. Together, they challenge the historical narrative, mixing true-life testimonies with powerful drama to create a theatrical hurricane of empathy, action and truth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 76

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Deirdre Kinahan

OUTRAGE

The Civil War

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

Dedication

Original Production

Characters

Outrage

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Introduction

Deirdre Kinahan

Three plays; seven years of warfare in Ireland; and my own fifty-three years of fascination with the bloody birth of our nation.

I grew up in the shadow of one of the major players in the 1916 revolution, Padraig Pearse. I used to play in the grounds of his mother’s house, racing across the fields and climbing the bizarre follies that dot the parklands of what was his extraordinarily progressive Gaelic school at the turn of the century: St Enda’s, Rathfarnham. I literally lived ten minutes’ walk from his home. I used to cycle along the stony paths through the woods of the grounds, play roly-poly on the small hill next to the old classrooms, peer in the window at the old desks and dusters, wondering ‘What was it all like back then?’ I was always one for ‘What was it all like back then?’! When my young friends wanted to play Red Rover or rounders, I might suggest a game of Henry VIII killing all his wives, or Anne Devlin refusing to rat out Robert Emmet when captured in Kilmainham Jail. The centuries always disappeared for me, and the stories grew and grew in my imagination. So to have a voice in Ireland’s commemoration of her revolution is honestly one of the greatest privileges and the greatest thrills of my writing career.

I was, however, initially wary of the ‘history’ play. It is a tricky beast. It can be didactic, overloaded with information or worse still… boring! So when Meath County Council asked me to write a play inspired by the events of the 1916 Easter Rising I was both delighted and a little nervous. Considering every Irish household has a story of brutal murder, deliberate starvation by local English landlords, or Granny hiding guns in her knickers to keep them safe from British soldiers, I wondered how Irish households might react to the actual truth of the period.

Similarly, there is the tragic reality of continued warfare in Northern Ireland; a rump state created in the midst of that time; and then, of course, Ireland’s strong culture of celebrity historians, professional historians, amateur historians, extremely vocal historians who might take great offence at the free imaginings of a playwright dancing on their turf! But I have always believed one has to put fear in one’s pocket when writing anything for public consumption so off I danced, sporting for a good old jig with Ireland’s ghosts.

***

Wild Sky was the first play – and where I learned how to tackle history in my own way. The play is pure fiction, but like all art it grows out of real human experience, human passion, human story. It is my attempt to turn back the clock, to walk the roads, to feel the heat, and dream the dreams that brought about Easter 1916. It is a play about radicalisation, what draws the young to revolution, what brings about the scream for change. Written through the prism of three ordinary, young, rural Irish poor, it is as much a love story as it is a comment on the time, and for me an homage to the very real ideals that took root having blown in from troubled Europe on Ireland’s ‘wild sky’.

The title comes from a poem by another neighbour, this time in my adopted county of Meath, Francis Ledwidge – poet, volunteer, amateur actor, socialist, lover, road-builder and republican – who inexplicably joined the British Army despite his nationalist credentials, only to be blown apart in the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 during the First World War. Ledwidge wrote the poem for his good friend, teacher and playwright Thomas MacDonagh, one of the Irish leaders executed with Padraig Pearse after 1916.

He shall not hear the bittern cry

In the wild sky, where he is lain,

Nor voices of the sweeter birds,

Above the wailing of the rain…

The story of Francis Ledwidge became the bedrock of Mikey’s experience in my play, and the story of another local woman, Kathleen McKenna, inspired the character of Josie. A neighbour told me in a chat: ‘There was a fella apparently from out your way that fought in the GPO and then walked home, the whole way home, and was never arrested, just went back to his farm like it all never happened and spoke very little about it.’ And that ‘fella’ became Tom Farrell.

***

The second play Embargo came about through a different route. It was commissioned by Dublin Port, Irish Rail and Fishamble Theatre Company who wanted to highlight the role of civil militancy during the Irish War of Independence against Britain – in particular the little-known national strike initiated by dockers and train drivers, who refused to handle munitions or transport British soldiers for a period during 1920–21, at the risk of losing their jobs or worse.

It was a strike I knew little or nothing about myself, and researching it brought me into the fantastic world of Irish socialism and her burgeoning labour movement at the turn of the century. I remember I was aghast to read about the various soviets declared throughout the country during that period and other great national strikes in 1918, ’19 and ’20, where vast swathes of the population downed tools and took to the streets. I was particularly enamoured by some of the slogans of the time like that painted on a red flag over Knocklong Soviet Creamery in County Limerick: ‘We make butter not profits!’ Why were these stories so hard to find? Why were they not part of the popular narrative surrounding our revolution?

I met a railman and historian, Peter Rigney, who took me into the archives of Irish Rail and there I tried to piece together a sense of the rail strike, and more generally a sense of the rail world at that time and how crucial it was to British governance and administration in Ireland. It was there that I also came across a short article telling the story of a train driver who refused to participate in the strike and so was tarred and feathered by the Irish Revolutionary Army – but still drove his train. I couldn’t get over the image: a man tarred and feathered but still roaring through the countryside in his steaming cab, still raging.

Embargo grew entirely out of that image, because to me it spoke so eloquently to the confusion, the mucky blur of political allegiance, personal circumstance, and the horrific violence of war, all war. Once again, I began to conceive of three characters who could embody the forces, passions and conflicting truths of that time. Gracie, fresh from the trenches with a penchant for ladies’ fabrics, is an unlikely hero, but he saves the fervent labour advocate Jane from her ultimate demise, thus drawing the ire of the traditional Irish revolutionary Jack.

The Irish War of Independence raged on for three years from 1919 to 1921. A genuine ‘David and Goliath’ story, where a deeply repressed population took on the might of one of the world’s greatest empires and brought it to a point of truce. It was – and is – a most extraordinary feat. An extraordinary moment of defiance, of sacrifice, of ingenious battle and justified rage. But it came at a cost, an immense personal cost not only to the flying columns of young, armed, revolutionary men whose deeds are well documented, but also to legions of Irish citizens who played their part, who won and lost, who watched their homes and villages burn, their children die and their future form from the carnage of war.

Tragically what emerged from this glorious fight was not the egalitarian, Gaelic, progressive republic declared to an empty street by Pearse in 1916, but a deeply conservative, guilt-ridden, poverty-stricken Catholic caliphate that limped on into the 1920s after a brutal civil war.

***

Outrage