0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Imaginarium Kim

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Made of cold metal? smooth plastic? fragile glass? Throw it away.

Even when it takes a human shape.

Live long enough, you see all kinds of heartless things happen. Sometimes that’s done in the name of convenience. At other times, loftier ideals such as elderly welfare take center stage.

Does everyone believe in that sweet charade? Probably not.

Is that solace enough? Absolutely not.

So, one old lady vows to never become part of the stinking world that takes replaceables for granted.

How to prove that she’s succeeding? By saying farewell in a special way.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

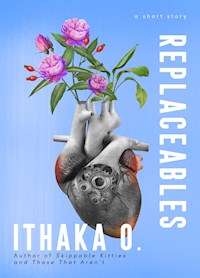

REPLACEABLES

A SHORT STORY

ITHAKA O.

IMAGINARIUM KIM

© 2022 Ithaka O.

All rights reserved.

This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

No part of this story may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Also by Ithaka O.

Thank you for reading

1

I knew this would happen. Theoretically, I’ve always known.

Realistically and practically, too, I’ve known, though when we first met and I decided to bring you home, I wasn’t thinking about this moment. I wasn’t even trying not to think about it, I simply didn’t think. The absence of consideration had come naturally to me.

Some would say that I didn’t bother to anticipate the inevitable in the way people don’t think about the time of parting when they purchase a sofa or a bed. Some would even compare you to disposables, such as plastic plates and cups, and tell me, What’s the big deal? That one’s gone, you get a new one.

I wouldn’t know how to respond to such statements of indelicacy. Cruel, indifferent people, such reasoners are. Knowing myself, knowing that I’d break into tears of righteous indignation, I wouldn’t dare argue against them.

I am cowardly like that. Age has made me more so. Nothing’s worse than being called senile when you know you’re right—and on top of that, if you show tears and they interpret that as weakness. So, I would merely secretly think to myself, They don’t know what they’re talking about. They know nothing about us. The only suitable analogy to my obliviousness back then would be the behavior of people in a decent, proper, perfectly valuable relationship of…

…what?

A parent and a child—in which case, I wouldn’t know if you are the parent or I am one.

A boss and an employee—in which case, surely you’d be the boss, because every time you tell me to do something for my health, I do it, fearing for my life. But then, legally, I own you; to all outsiders, I am officially the boss.

Perhaps we are friends, then. Yes, friends. That sounds about right. It’s an oddly one-sided friendship, in every aspect. Me giving you shelter, electricity, and a purpose. You keeping me alive so that I can give you those things. But who can say that odd friendships aren’t as valid as what others deem normal?

So, my not considering our eternal parting was like two people shaking hands for the first time and not imagining the other person’s funeral right then and there. All I thought about back then, at that shop full of your counterparts—all smooth, glistening below the strategically-placed, gentle lighting—was:

Must I get an aidbot?

I could still smell the hospital on my clothes. Somehow, just by sitting in a closet in my hospital room for a month, my coat and shawl and long skirt had managed to smell like sanitizers and other sick people. They’d soaked up the atmosphere of that place. When I’d made a remark about that, the nurse had smiled and told me that I had a very acute sense of smell, and that it was a good thing for someone so old.

That phrase, “for someone so old”—oh, how I hate it!

As to my shoes, they’d taken those away. I didn’t need them, they claimed. I sat in a wheelchair and wore a pair of slippers (which I don’t count as proper shoes) over thick socks.

It was an autumn day, pleasantly chilly for the healthy younger ones, less so for me, but nevertheless preferable to the sweltering heat of summer or the freezing blizzard of winter. Autumn, the middle state, the season in which even the rooms without air conditioning meander around that all too elusive thing called room temperature—that was when we met.

The technician at the shop kept asking my daughter and son questions. They stood behind my wheelchair, exhausted, half listening to the technician’s remarks, half catching their breath. They’d taken turns pushing the wheelchair all the way from the main street to this little alley shop. Their strategy of getting an electronic state-of-the-art wheelchair, precisely to avoid having to push it, had backfired. The low buzzing and wheezing had made my head hurt. Since they were nice kids—still are—they offered to push it manually, even though their joints, much like mine, weren’t doing that great.

On any normal day, I would have declined their kindness. But on that day, I accepted, because both of them felt terrible for having made me stay at a hospital for longer than necessary, and then taking me to that shop. They were so eager to exert themselves as a form of self-punishment. I had to let them help.

Besides, I appreciated their guilt; though, let me make this clear: I never blamed them for having careers and families of their own, and therefore not allowing their lives to revolve around mine. I told them so, too, on multiple occasions. But them being good kids—I think I can be proud of that, that I raised nice kids who are capable of feeling bad for not personally taking care of their ninety-year-old mother, which was how old I was back then—they ignored my comments about how they shouldn’t blame themselves. They kept on continuing to feel bad anyway.

Some of the cruel, indifferent people who equate you to a sofa or a bed, and worse, to a plastic plate or cup, might say that feeling bad that way makes no sense. That, therefore, my children aren’t “good” or “nice,” they’re just being silly. At which I’d break into tears of frustration and tell such people, It’s not about whether or not it’s feasible to watch your elderly parent all day long, it’s about the desire to do so, had it been possible.

Of course, such a thing is always impossible. Time-wise, and life-wise. Children—even those who are in their sixties—have their own life. Their own children. And their children.

So, my daughter and son stood behind my wheelchair, guilty and terribly exhausted. The technician stood next to me.