10,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

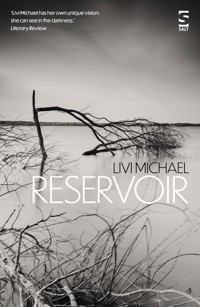

At the International Conference Centre in Geneva, Hannah Rossier, formerly Annie Price, comes face to face with Neville Weir, someone from her childhood whom she never expected, or wanted, to meet again. As Neville's reasons for attending the conference become clear, the dark waters of Hannah's past start to rise. Hannah is a psychotherapist, with a specialist interest in memory and how connections are made between past and present. She has reinvented herself successfully, moving from a small northern town in England to Lucerne, Switzerland, with her husband, Thibaut. Nobody, not even Hannah, knows the full truth about herself. Her 'memories' consist of glimpses of the place where she played in childhood, known simply as 'The Wild'. Over the three days of the conference she has to decide whether she can avoid Neville, or whether she should submit to an encounter with him and with her past. And in her keynote lecture about the neuroscience of memory, how much to conceal or reveal. But can her specialism save her from drowning?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

iv

LIVI MICHAEL

RESERVOIR

RESERVOIR

viii

CONTENTS

I

The Wild began where the gardens ended.

In the gardens they could name the plants and animals, privet, rose, squirrels, magpies, cats, but in the Wild, there were alien insects, small, furred creatures clinging to the undersides of leaves, droppings from animals they never saw. And a mass of foliage, spotted, striped or mottled.

Everything was tangled, variegated. So many shades of green: the lime green of new leaves or moss, the dark, polished green of holly or laurel, grey-green splotches of fungus.

Together they skidded and slithered down the rough paths towards the place where they were not supposed to go: the stagnant water, the trailing reeds.

Their eyes burned like the eyes of animals on the scent of prey. They were wood-elves, or savages with spears, they wore garlands and flourished green boughs, their clothes flapped around them like animal skins.

Sometimes they lay on the ground, panting, squinting at a dazzle of sun through a net of leaves. The leaves were quivering, edged with fire, and beyond them, the sky was a burning, infinite blue.

As she lay there, breathing it in, her mind became empty and still. She was free.

But that was then.

That was before.

II

Somewhere in the universe an asteroid struck the surface of a planet, a meteorite plunged into a methane sea, and at the International Conference Centre in Geneva, Hannah Rossier came face to face with Neville Weir.

‘Annie Price!’ he exclaimed, his eyes widening.

Every vertebra of her spine stiffened.

‘Hannah,’ she said. ‘Rossier.’

Neville’s eyes widened further. ‘You changed your name?’

‘No!’ she said, a little too vehemently. ‘My name was always Hannah. And I married.’

‘Oh, so,’ he began, and at the same time, she said, ‘It was just the children – at school – calling me Annie.’

Neville’s gaze grew complicit with understanding. ‘Of course,’ he said, ‘and I was always Weirdo. For obvious reasons.’ He smiled deprecatingly, then his eyes widened again. ‘But – Hannah Rossier? Professor Rossier? You’re the speaker?’

She dipped her head in acknowledgement. Why? she was thinking. Why him? Why now?

‘But you’re the whole reason I came to the conference!’ Neville exclaimed. His expression had changed to one she couldn’t quite name. Almost predatory.

‘Really?’ she said, discouragingly.

‘Your paper, on the neuroscience of empathy – extraordinary.’

She looked across the atrium, for someone, anyone, she 3knew. With a rush of relief she saw the clipped, silver head of Jopi de Groot. It was turned away from Hannah and only visible because Jopi was half a head taller than anyone else, but still someone she could claim.

‘… set off a whole new train of thought—’ Neville was saying.

‘If you’ll excuse me,’ Hannah said, stepping away from him, ‘there’s someone – I have to …’

‘Oh, of course,’ Neville said. ‘But how extraordinary that we should meet up here, like this – are you staying here too? In the hotel?’

Hannah could feel her cheeks tightening, her smile becoming fixed.

‘I tell you what,’ Neville said, ‘there’s a lovely little bistro here on the roof – do you know it?’

But Hannah was walking away. ‘I have to go,’ she said, over her shoulder. She should have added something like ‘See you soon’, but she was already out of earshot. She could still feel his gaze on her as she retreated, but she had to navigate through all the people in the atrium, who had collected by some unseen chemistry into molecular clusters of threes and fours, or larger groups moving with a tidal rhythm.

She could no longer see Jopi’s silver head. She had lost her in all these people, she had lost herself. Hannah stood for a moment, bewildered by the acoustic hum of so many voices, so much glass and light. She turned slowly, uncertainly, in a little space on her own. Until suddenly, there she was, Jopi, her friend, who had organised this conference, slicing through the crowds with her head lowered. She wore a linen suit in white and grey, flowing out at the sides like wings. Only as she reached Hannah did she look up, with a smile of startling ugliness: bad teeth, crooked jaw.4

‘Ma cherie!’ she exclaimed, always less formal than the Swiss. She held her arms wide.

‘Jopi,’ Hannah mumbled, submitting to the embrace. ‘Ça va?’

Jopi introduced her to the centre manager, Isabelle, who had a narrow face and emphatic features. She nodded at Hannah then spoke to Jopi so rapidly that Hannah’s French, even after all these years, wasn’t quite up to it. ‘Ah,’ Jopi said to Hannah, as Isabelle left, ‘complaints, already! What would we do without them?’

Then there were two students, Bonjour, bonjour! Volunteers who would help the conference run smoothly, provide water, check the sound. They looked so alike Hannah knew she would confuse their names. Jopi gave her a programme and showed her to the main lecture theatre, an enormous circle with a domed ceiling where the seminars and plenary sessions would take place.

‘Impressive, no?’ Jopi said. ‘This is where all our funding goes these days.’

Hannah remembered to smile. Neville, she was thinking. He was so much bigger than she recalled. Obviously, she hadn’t seen him since they were children, but the Neville Hannah remembered had been skinny and undersized. Following the girls around because the boys wanted nothing to do with him. The girls didn’t either but they were less likely to beat him up. Now he seemed massive – not overly tall, but very broad. She remembered his sideways movement, crab-like, when she had given her name, and shuddered.

‘Are you well?’ Jopi said, face creased like a pug’s with concern.

Hannah said it was nothing, a headache, she had aspirin in her room.5

One of the students – François, was it? Pierre? – offered to take her through the glass tunnel that connected the conference centre to the hotel, but Hannah declined.

‘But you’ll join us for dinner?’ Jopi said. ‘You haven’t seen the restaurant yet – it’s spectacular!’

‘Of course,’ Hannah said, nodding vigorously. She would join them for dinner, in the Restaurant du Lac, at eight.

Only when she was in the lift (which was transparent, so she was hardly out of sight), did she search through the programme.

She had to read it twice before finding his name. There it was, in small print. His lecture was the day before hers: ‘Sense and Censorship: the Psycho-Politics of Narrative’.

What did that mean?

There was nothing else, no details. There must be an abstract somewhere, but Hannah was so used to these conferences that she’d barely looked at the materials they’d sent her online.

Preoccupied, she almost forgot her floor, hurrying out hastily before the doors closed. Then she stood baffled by the long corridor with its marbled, shiny floor, its identical doors.

But she was booked into room 422, her card key told her. Which, as it turned out, was near the lift.

How could it be, she thought, sliding the card-key into its slot, that the two of them, from the same small town, the same under-achieving school, had ended up in the same professional field? She’d not seen Neville since primary school. He’d passed the 11+, she remembered, which was unusual enough for their area, and would have gone to the boys’ grammar school, but she, almost uniquely in the history of Rosehill Primary, had gained a scholarship to the private grammar. Their paths had never crossed again.6

Until now.

The hotel room was painted in a shade that in England might be called soft olive, soothing, unobtrusive. The window looked over the lake and there was a bouquet of green flowers, some kind of orchid, euphorbia, hypericum, on the sill. They seemed cunningly designed to look artificial but were in fact real. Otherwise the room was impersonal, a desk for a laptop, a wifi code near the sill. Everything was automated, operated by her card.

Blades of light sliced through the window-blind onto the bed. Hannah sat down on it, looking at the programme again. There, on the back was his biography, Dr Neville Weir from Nottingham University. He’d written a book about language development, Authoring the Child. Not out yet – which was why she hadn’t heard of it, presumably.

She tapped his name into her phone. And then a thought came to her that set tiny pulses hammering in her forehead. Surely Neville would have done the same.

He would have looked the main speaker up.

He must have known who she was.

III

All afternoon, Hannah remained in her room. She tried investigating Neville, but curiously, there was not much to find. There was an FB account, no longer active, but which seemed to suggest a wife and two sons. His LinkedIn was out of date, there was nothing on Twitter. Apart from his book, he’d written an article, The Pathology of Shame, but she could only access the abstract.

An understanding of pathological shame is critical for assessing the psychological effects of developmental trauma …

Nothing ground-breaking there. It was hardly enough to get him invited to an international conference like this. Although Jopi did sometimes invite people who were not well known. She liked to think she was boosting people’s careers.

Was that why Neville was here? Evidently, she wouldn’t find out from his online profile. She would find out, she supposed, in person. Face to face. Unless she spent the entire three days avoiding him.

Or went home.

On impulse she phoned her husband. He would come for her if she asked him, although they lived nearly three hours away in Lucerne. She would say she wasn’t well, offer to leave her PowerPoint presentation with Jopi.

She rang him twice but it went straight to voicemail. Thibaut Rossier n’est pas disponible en ce moment.

She wondered if he’d taken his students out for drinks 8– something he would only do in Hannah’s absence, because he knew she would disapprove. The bill would be enormous, equivalent to the Gross National Debt of some minor country.

Pointless to argue that with him. He loved his students, and they adored him. They kept him young, he told her. Whenever the subject of his retirement came up he would say, Je suis trop jeune.

He was 63.

They had met in Switzerland, at a conference like this one. He was not a psychotherapist, but a chemist, researching therapeutic drugs. They had married eleven years ago, when she was 40 and he was 52. They had no children. Hannah didn’t want them. In the course of her career, she’d seen enough of what parenting could do. Thibaut had one son, Christophe, from his first marriage. Hannah had assumed he wouldn’t want any more, at his age.

When they’d married, and she’d moved to Lucerne, she’d felt as though her real life could finally begin. As though until then, she’d been frozen in suspension. Marriage was like tying the loose ends of herself into a different whole. But now she saw how quickly that could unravel.

Hannah’s forehead crumpled as she held onto her phone. But it was ridiculous. What did she imagine would happen? What could Neville possibly say, or do?

She should stop thinking about him.

She put the phone away then stripped off her outer clothing. In her underwear and camisole she began an exercise routine, stretching, breathing deeply, taking her attention to the soles of her feet, the base of her spine.

Time passed with an artificial slowness. Hannah had spoken at many conferences, stayed in innumerable hotels. She was 9familiar with the languor of hotel rooms, which she attributed to their unfamiliarity, the absence of known objects. It was as though the ordinary trappings of furniture and books wove her into a temporal frame.

Normally the anonymity soothed her, but now she felt out of alignment, unfocused. There was discomfort, not a pain exactly, beneath her ribs. She went through her lecture until she could no longer concentrate. At some point she realised she was seeing it through his eyes.

What would he think of it?

Would he pick her up on that point?

What questions was he likely to ask?

She imagined him in the lecture theatre, sitting in front of her. Whichever way she looked, he was there.

Again she rang Thibaut; he was still unavailable.

‘Thibaut,’ she said. ‘Can you call me, please?’

Her voice had cracked a little, which she hadn’t intended. ‘I’m fine,’ she added. ‘I’ll be going to dinner at eight. If you get this before then – just – give me a ring.’

Was that better?

What would she say?

Suddenly cross with herself, she tucked her phone into her bag. It was a little before seven. She had a shower, and changed into the other suit she’d packed. It was blue-grey, almost identical to the navy one she would wear for the lectures. Over the years, she’d perfected a minimal wardrobe for short conferences, two suits, four tops, nightwear, one set of casual clothes. Because it was evening, she wore a silky top in pewter with the blue-grey suit, sandals with a tiny strip of glitter, and earrings. She applied very slightly more make-up.

Then she looked at herself in the mirror.

Her mouth was set in a thin, strawberry-coloured line, 10her eyes were greenish, veiled. Her hair was too severe. She pulled a strand of it forwards, realised the strand was grey, tucked it back.

She’d read all the style magazines, had her colours done, knew her shape. Oddly, whatever she did, she always looked the same. Not like Jopi, who had the gift of transforming herself with little touches, an exotic pendant, a flamboyant scarf. Last year, she’d opened the conference in a slinky evening dress that should have looked incongruous but didn’t. Everyone had admired her. Jolie laide, that was what the French called it.

What was Hannah? Fade.

It remained a mystery to her that Thibaut had singled her out, when he had all those admiring students.

You were so quiet, so discrète, he’d said.

Like a secretary?

A little like a secretary.

That’s why you wanted me? Because I looked like a secretary?

No, he’d said, because I thought you’d be wild in bed.

Usually that memory made her smile, but not now. When she practised her smile in the mirror, her eyes gave her away. Somewhere behind the mascara, she was still Annie Price, that frightened child.

She would enter the restaurant by the side door. If Neville was there she would just leave. She could always eat in her room.

She should be a few minutes late, so she could see him before he saw her.

It would take her nine minutes, she estimated, to walk from her room to the restaurant, which was on the lower ground floor. So she should set off just after eight. There was a little more than half an hour to wait.11

She sat down on the bed again, resisting the urge to call Thibaut one more time.

IV

The restaurant was packed. It was impossible to work out who was sitting where. Hannah managed to identify Jopi by her laugh, coarsened by innumerable cigarettes, but she couldn’t tell who was with her. So she kept walking, shoulders back, smile taut.

Jopi rose in greeting. ‘Hannah!’ she exclaimed. ‘Over here!’ She wore a peacock blue jumpsuit, with a brilliant pink jacket. Her hair was waxed into short spikes. Hannah almost stumbled over the trailing strap of some woman’s handbag, and was forced to look down. Pardon.

‘Here we all are,’ Jopi said, as Hannah advanced towards them, slowly, it seemed, so slowly. Finally she managed to scan the other faces and allowed her smile to become warm.

‘This is Professor Rossier, our main speaker,’ Jopi said, ‘and this is Karl Hartmann, from Frankfurt,’ a tall, ginger-haired man rose smiling, ‘and Heidi Kruse, from Denmark.’

Hannah registered their lightning assessments of her, the interest in Karl’s eyes fading. She’d reached that age when only women gave her those appraising looks, evaluating mainly what she wore. And of course, she did the same, automatically, instantaneously. Heidi had steel-rimmed glasses and a sharp smile. She wore a multi-coloured woollen suit that looked as though she might have knitted it herself.

‘Isabelle, you know.’ Isabelle half rose, smiling, until Hannah waved her down again. She wore stretch leather 13jeggings, a loose paisley top and pointed leopard-skin mules.

Hannah eased herself into her seat. ‘This is nice,’ she said, nodding towards the window where the lake lay like a plate of light.

‘Isn’t it? And yet Isabelle was just telling us that she’s planning to move.’

‘Really?’ said Hannah.

‘Only to Annecy. I will still work here.’

Jopi poured wine into Hannah’s glass. ‘So you will join the commuters from across the border.’

‘Exactly. It’s so much cheaper. And Annecy is really pretty.’

‘But I thought Lucy worked in Besançon?’ Heidi said.

‘Lucy works everywhere,’ Isabelle replied. She turned to Hannah, adding, ‘She curates art exhibitions in different cities – Lyons, Nice. My apartment, and her apartment, are full of boxes. Boxes, boxes! We can never find anything. Only last week, her son came to stay, and her mother visited, and I had left the wrong box out, and they put this CD in the computer for him and it was that bizarre woman who operates on herself – you know – Odile. I came in just as she was about to slice off her own nipples with a razor, and Lucy’s maman said, “Are you sure this is Little House on the Prairie?”’

Jopi cried aloud, Karl laughed, and Heidi said, ‘I don’t think we should give that kind of art a platform – it’s too similar to what some of our clients do to themselves.’

‘Oh but art and mutilation are two sides of the same coin,’ Jopi said. ‘Don’t you think, Hannah?’

Hannah took a piece of bread from the basket and said that anthropologically that was certainly true, many tribal peoples self-mutilated.

‘Exactly – that is what art is – you take one thing and deform it into something else.’14

‘Transform,’ said Isabelle, but Jopi ignored her. ‘It’s in the human genome,’ she said. ‘It’s what we do.’

‘I think there are less painful ways of transforming oneself,’ said Karl. ‘Take a course – move house.’

‘Ah, but then you only take yourself with you,’ Jopi said.

Heidi said she’d had enough of moving. For years she used to drive between Denmark and Sweden. Now she’d settled in Helsinki, only a short walk from the university. Karl said he loved to travel, he’d recently spent a year in New York and was going to try for another fellowship. He smiled at Hannah. ‘What about you?’ he said. ‘Have you moved around much?’

‘A little.’

‘Do you have any favourite cities?’

‘Tokyo,’ she replied to general exclamations of interest.

‘What was that like?’

‘Did you live there?’

‘Did you like it?’

‘I loved it,’ Hannah said.

‘Now there,’ said Karl, ‘One would truly have a chance to change oneself – become someone different – don’t you think?’

‘Are we ordering food?’ Hannah said to Jopi.

‘Certainly we are,’ said Jopi. ‘I’m starving!’

There was a protracted discussion about the relative virtues of La Chasse and Filet de Perche. Jopi said they should have something they could all share, and Karl suggested Fondue Bourguignonne, but Jopi said that Hannah didn’t eat meat and everyone looked at her.

‘It’s fine,’ she said. ‘I’m happy to order for myself.’

Heidi said, ‘Well, what about raclette – and the asparagus, perhaps?’

Hannah had given up telling people she didn’t eat cheese either, there was hardly any point being vegan here.15

After some negotiation, during which Karl and Heidi decided to share a side dish of chicken livers, it was agreed they would all have raclette. Jopi called the waiter over to place their order. ‘And wine! Lots of it,’ she said.

The talk moved on to their hotel rooms, too warm, no view. Hannah looked out, towards the lake. There was a shimmer of colour in it, an effect like shot silk. Then she thought she heard her phone, and reached for her bag, feeling a twinge in her hip as she bent to the side.

There was a bump, then a scuffling noise and a clatter.

‘Oh, I’m so sorry,’ Neville said. ‘No, no – you must let me pay for that.’

Hannah straightened slowly.

‘I’m so clumsy,’ Neville said, dismayed. Behind him a woman was brushing her jacket.

‘Like the proverbial bull,’ he said, helping her to straighten it, and there was a little fuss of apology and conciliation, before he turned towards Jopi. ‘Do you mind if I join you?’ he asked.

‘Of course!’ Jopi said. ‘See, the chair is already waiting! Everyone, this is Neville Weir, our psychopathology expert.’

‘Hardly that,’ Neville said, manoeuvring himself awkwardly into the chair between Isabelle and Heidi. He directed a small smile at Hannah.

‘I hope you’re happy with raclette,’ Heidi said. ‘We’ve just ordered.’

‘My goodness, yes!’ Neville said. ‘I love raclette.’

‘There should be enough for everyone,’ said Karl. ‘But we’ve ordered chicken livers as a side.’

‘Ah, I don’t eat meat,’ Neville said.

‘Another one!’ said Jopi. ‘You English and your scruples! Anyone would think you hadn’t invented the hunt!’16

‘I’m afraid we don’t do much hunting where I come from,’ said Neville.

‘Yes, Jopi,’ said Isabelle, ‘You are guilty of cultural stereotyping!’

‘Well, but there are only two English people at our table and neither of them eat meat. It smacks of guilt to me. Neville, this is Professor Rossier, your fellow abstainer.’

‘We’re old friends,’ said Neville, warmly.

‘Really?’ said Jopi.

Hannah couldn’t look at him. She picked up the piece of bread on her plate and broke it, once, twice, as Neville launched himself into the tale of how he’d booked the conference specifically to hear Professor Rossier speak, and then, it turned out, they were from the same small town in the north of England, the same small primary school.

There were exclamations of surprise and delight.

‘That’s so sweet!’ said Heidi. ‘You came all the way here for your schoolfriend!’

‘Oh, I didn’t even know!’ Neville said, and Hannah glanced at him sharply. He seemed manifestly open, naïve. ‘Of course, she wasn’t Professor Rossier then,’ he said.

‘Not at primary school!’ Isabelle joked.

‘What a wonderful surprise!’ said Jopi. ‘You travel all the way from New Zealand and meet your childhood friend!’

‘I know!’ Neville said.

Hannah said, ‘You’ve come from New Zealand?’

‘Auckland,’ said Neville.

Heidi said, ‘Now that’s a long way …’ and at the same time Hannah said, ‘I thought you were at Nottingham?’

And instantly realised he would know she’d looked him up. Neville ducked his head in acknowledgment. ‘I was – until earlier this year. But I was offered this post, and really – I 17couldn’t refuse. New Zealand is one of those countries I’ve always wanted to visit.’

‘Me too!’ said Karl, but Heidi said, ‘Still – it’s a long way to come for a conference.’

‘Oh, I’d booked the conference well in advance,’ Neville said. ‘Couldn’t resist – anything organised by Jopi here – and of course, I was particularly interested in Professor Rossier’s paper.’

He smiled at her with his yellow teeth.

Hannah could hardly leave – she’d already walked away from Jopi once, pleading a headache. She poured herself more wine, gazing steadily at the glass and said, ‘Well, I hope it lives up to your expectations.’

‘So do I!’ exclaimed Neville. ‘Or I’ll be claiming my money back!’ He laughed loudly, and everyone laughed with him, but Heidi said, ‘Didn’t the university pay for you?’

‘Oh no,’ Neville said. ‘I booked it myself. So I definitely want my money’s worth.’

He was still looking at Hannah, she could feel it, although she wouldn’t look back. She was furious with him, with herself. Her heart was pounding.

‘So tell me,’ Karl said, leaning forward, ‘New Zealand – is it wonderful?’

‘It really is,’ said Neville, pouring wine. ‘It’s everything I’d hoped it would be, and then some.’

They were interrupted by the arrival of the raclette. A waiter brought a small brazier to the table to heat the cheese, and more waiters followed, bringing potatoes, gherkins, plates. Karl turned to Neville.

‘You know, I once drove across Canada,’ he said, ‘and checked myself into a motel near Ottawa, quite by chance – no pre-booking – and the – what do you call it – hotelier?’18

‘Proprietor?’ suggested Neville.

‘Exactly – the proprietor turned out to be my first girlfriend! She’d married a Canadian and moved to Ontario. They were running the hotel together!’

After that, everyone had a story of remarkable meetings.

‘That’s the beauty of travel,’ Neville said. ‘Wherever you go, you meet someone, or something from home.’ He wasn’t looking at Hannah.

‘You might as well stay where you are!’ Jopi joked.

Without appearing to, Hannah observed Neville. It was one of the tricks she’d learned in her profession, along with controlling even the minor muscles of her face. His manner was bluff and hale, but beneath that she detected something different: cramped, as though forced to grow without light.

He reminded her of one of those stores she’d seen in reproductions of nineteenth-century mid-western towns. False fronts made them seem large and expansive on the outside, but inside everything was constricted and cluttered, dark.

‘So tell me,’ Jopi said to Hannah. ‘What was Neville like as a little boy?’

‘Oh, hopeless!’ Neville said, before Hannah could speak. ‘The perfect nerd! Billy-no-mates. You wouldn’t recognise me – I was weedy and skinny – not like now,’ he poked his paunch regretfully, to make them laugh. ‘Hannah, now – she hasn’t changed at all! The moment I saw her I was transported back to primary school!’

‘It’s true!’ said Jopi. ‘You’ve not aged in all the time I’ve known you!’

‘Of course, you are only twenty,’ said Isabelle and everyone laughed again.

‘I wonder how many friends we would recognise from 19school,’ said Jopi. ‘Some people change so much. Me – I was always the naughty one!’

‘So, no change there,’ said Karl, leaning forward. Was he flirting with her? Jopi had that effect on younger men.

‘I don’t think we really change,’ said Heidi. ‘Inside, I am still ten years old!’

‘Me too,’ said Jopi, ‘and then I look in the mirror!’

‘But the child is still there,’ said Neville. ‘In the eyes.’

‘L’enfant reste toujours dans l’esprit,’ Isabelle said, smiling fondly at Hannah. As if she knew her. As if any of them did.

She put her glass down. ‘But then, aren’t we wasting our time?’ she said, looking round at them all. ‘Isn’t it our business to help people to mature?’

Heidi said, ‘But do we ever leave that child behind?’

‘Would we want to?’ Jopi said.

Hannah filled her glass again. She felt a dark, primitive urge, emboldening. ‘But don’t you find it irritating,’ she said, ‘when you meet someone from the past, who thinks you are still as you were thirty or forty years ago? That you haven’t moved on?’

She was looking at Jopi, not Neville.

‘True,’ Karl said. ‘That’s what families are like. I have two older sisters and whenever I go back home, I’m always the baby of the family!’ He pulled a face then beamed.

Jopi glanced from Hannah to Neville. ‘Perhaps you should tell us what Hannah was like as a little girl?’ she said.

Neville sat back, appraising her. Hannah raised her eyes slowly, staring back. ‘Oh, she was a goody-goody,’ he said. ‘She never put a foot wrong. Always first in class, first to hand in her homework. Teacher’s helper …’

Hannah felt a spark of rage.

‘So, you were a good little girl?’ asked Jopi.20

‘I worked hard,’ Hannah said. ‘I realised, early on, that I would get nothing without working for it.’

‘And so quiet!’ Neville said. ‘You would hardly know she was there.’

You knew, Hannah thought. She could feel her neck flushing from the wine.

‘That is how women get on,’ said Heidi. ‘Being the rebel, the loud one, only works for boys!’

‘And she did get on,’ Neville said to Heidi. ‘Look at her now!’

‘Things change,’ Hannah said.

‘Only on the surface,’ said Neville. ‘I’m sure you still work hard at being good. At what you do,’ he added.

Hannah felt her face flush as well as her neck. ‘You see that’s what I mean,’ she said, looking at Heidi, then Jopi. ‘That kind of thinking – it’s another kind of stereotyping. It’s lazy.’

She looked at Neville then and saw something flare in his eyes. ‘And, in certain respects, cruel,’ she went on. ‘Isn’t that what we try to avoid? Pigeon-holing people – especially children – marking them out as naughty or deviant or good, so they carry that label with them for the rest of their lives?’

‘Well,’ said Neville, smiling at her, ‘why don’t you tell us what you were really like?’

‘Oh, not on the first night!’ cried Jopi. ‘We should save that for the final evening!’

Everyone laughed, and the talk turned to the itinerary for the rest of the conference. Isabelle said she’d thought they would eat out on the following evening – she’d planned a little tour, and on the last night a river cruise and a meal on the boat. This was greeted with delight by Karl, Heidi and Neville.

‘There will be others joining us,’ Isabelle said. ‘Lots of people here have never been to Geneva before, and it’s so 21beautiful, it would be a pity to leave without seeing it properly.’

‘Of course, Hannah knows it very well,’ Jopi said. ‘So if you like, we could do something different?’

But Hannah said she had her own plans. ‘Do go with the others,’ she said to Jopi.

‘You’re sure?’

‘I’ve got lots to do. And I still have to work on my lecture.’

‘Well, but we will see you at some of the sessions?’ Jopi said. ‘Heidi is speaking tomorrow, and Neville on the following day.’

Neville was looking at her with that cynical smile, eyebrow raised. ‘Of course,’ she said. What else could she say? ‘I wouldn’t miss it.’ She looked away from him.

‘Good, then – that’s all settled,’ Jopi said.

The conversation moved on to who had visited Switzerland before, and when and where, while all around them currents of noise from the neighbouring tables rose and fell, and through the great glass wall the lake lay like a pale shadow, paler now than the sky.

Just for a moment, but with a piercing clarity, Hannah saw that other stretch of water superimposed upon it, its greenish lights, its smooth surface, almost opaque. She blinked, once, twice, and met Neville’s eyes. He smiled sadly and looked away.

There was a discussion about dessert, but Heidi said she never ate dessert any more, and she didn’t want to be too late getting to bed – it was an early start for her in the morning. Hannah seized the opportunity. ‘Me too,’ she said, picking up her bag.

‘But you don’t have to get up early,’ Jopi protested.

‘I always do, though,’ Hannah said. ‘I like to walk first thing, before breakfast.’

‘Which room are you in?’ asked Neville, and she flinched.22

‘I’m sorry?’ she said.

‘I was hoping we might have a chance to catch up at some point.’

‘I’m sure we—’ Hannah began, but Karl interrupted, ‘You can’t just ask ladies for their room number – people will get the wrong idea!’

Karl was drunk, of course, but everyone laughed politely, and Isabelle said, ‘Ladies! Whoever uses that word any more?’ Jopi said she liked it and was thinking of reclaiming it, then Heidi stood up decisively, saying if she ate any more she’d have indigestion all night, and gratefully, Hannah stood up too.

‘Good night,’ she said. ‘Sleep well.’ And before the goodbyes could become protracted, she began making her way between the tables, waiting for people to adjust their chairs.

Heidi followed her, saying something, but it was noisier now, so many people, all those strands of conversation rising on a tide of wine. Hannah could still hear Jopi’s laugh as they left, and see the shining curve of the lake through the glass.

‘That’s better,’ Heidi said, as soon as they were through the doors. ‘I love conferences, but they’re so exhausting – mainly because one has to be sociable!’

Hannah smiled.

‘Ah – there you are!’ Heidi said, retrieving her card key from the depths of her bag. It was a capacious bag, with an old-fashioned clasp. ‘One year I lost it and it caused no end of trouble! Well – I’m only one floor up – I should take the stairs.’