6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

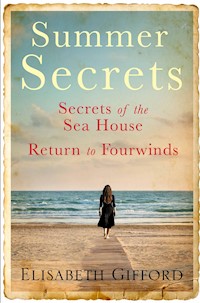

***Shortlisted Author For Historical Writers' Association's Debut Crown For Best First Historical Novel*** What will it cost to hide your deepest secrets from those you love most? At Fourwinds they gather: Alice and Ralph, Patricia and Peter, to celebrate the marriage of their children. But the bride is nowhere to be seen. What could have caused Sarah to vanish? As both families search for the answer, the past floods through the corridors of the old house. What secret has Ralph been keeping from his wife? What is it about Alice's wartime encounter with Peter that has haunted her ever since? Return to Fourwinds is a sweeping, lyrical story of the things we choose to tell and the secrets that we keep.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Elisabeth Gifford studied French Literature and World Religions at Leeds University. She has written articles for The Times and the Independent, and has a Diploma in Creative Writing from Oxford OUDCE and an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway College. She is married with three children. They live in Kingston upon Thames.

Also by Elisabeth Gifford

Secrets of the Sea House

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2014 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Elisabeth Gifford, 2014

The moral right of Elisabeth Gifford to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 114 2E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 115 9

Printed in Great Britain.

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Contents

Chapter 1 Derbyshire, 1981

Chapter 2 Valencia, 1931

Chapter 3 London, 1932

Chapter 4 Valencia, 1932–1936

Chapter 5 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 6 Manchester, 1935

Chapter 7 Manchester, 1935

Chapter 8 Manchester, 1939

Chapter 9 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 10 Oxford, 1940

Chapter 11 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 12 Buxton, 1940

Chapter 13 Buxton, 1940

Chapter 14 Derbyshire, 1981

Chapter 15 Buxton, 1941

Chapter 16 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 17 Buxton, 1941

Chapter 18 Buxton, 1941

Chapter 19 Manchester, 1941

Chapter 20 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 21 Holland, 1945

Chapter 22 Gairloch, 1981

Chapter 23 RAF Kirkham, Blackpool, 1948

Chapter 24 Barnstaple, 1949

Chapter 25 Birmingham, 1966

Chapter 26 Leeds, 1976

Chapter 27 Gairloch, 1981

Chapter 28 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 29 London, 1981

Chapter 30 London, 1981

Chapter 31 Fourwinds, 1981

Chapter 32 Birmingham, 1981

Chapter 33 Birmingham, 1981

Chapter 34 Gairloch, 1981

Chapter 35 Fourwinds, 1993

Acknowledgements

Read on to Discover More a Bout

Q&A with Elisabeth Gifford

Reading Group Questions

To Josh, Hugh, Kirsty and George

CHAPTER 1

Derbyshire, 1981

As Ralph Colchester reached the foot of the hill and began to drive up towards the village, he thought wearily of Fourwinds, the large Georgian house that was waiting for him at the top, of the chaos that would be eddying through the rooms with the Donaghues already there to help, the noise of hammering from the marquee going up on the lawn. It was late afternoon, the air warm. The simmering green fields stretched away under a sky of unimpeachable blue.

On impulse he took a left turn into the longer route home, Draycott Lane, an ancient way deeply embedded between banks and hedgerows. Barely the width of a cart, it had been tarmacked over decades ago, but two rows of weeds persistently broke through to mark the old wheel runnels. And there was the cottage, hidden away in a bend, a huge elm rising up from the opposite bank, spreading its massive branches across the lane.

He stopped the car. The cottage was looking a little dilapidated. A pile of cement bags in the garden spoke of renovations. He’d heard a young couple had taken it on recently. The upstairs curtains were still drawn. Looked like they were commuters then, not yet returned from town.

He thought back to the day when, still in uniform, laughing, he’d carried Alice over the threshold. They’d hardly noticed the damp walls and the soggy thatch at first. They’d seen a glass moon rising over the black silhouette of the hills, heard the scream of the fox in the darkness. In the morning, blue woodsmoke rising through the winter trees. The splash of the stream sounding through the cottage rooms.

No space in there to be anything other than close, to be together. One frosty and moonlit night, Alice had gone out with a handful of salt and sprinkled it round the border of the frozen garden, a shining barrier to stop any harm from reaching them, she told him, an old country custom for newly weds, half done in jest. They had lain in bed, the salt sparkling on the frosty ground outside. Inside the circle, she said, they would always be open and true with each other, intimate and secret from the rest of the world.

And then, in time, came the children, and with them the great romance of moving up to the large Georgian place and renovating it as their home. A stream of purposeful years followed, building a family life together.

But now, the children gone from the echoing rooms, he had turned round one morning and realised that they were not so much a couple as two people with interconnecting schedules, their lives glancing off each other like two balls bouncing around an empty room. He was forever busy with the law firm in Uttoxeter, Alice absorbed in lecturing in social studies at the college. In the evening they came home, listened to music, read through books or papers from work, watched the news at ten, always polite and agreeable.

Last winter, with all three boys absent, he’d been aware for the first time how terribly silent the village was. Late one night, with snow covering the countryside, he’d looked out of the window and seen the empty glow blanketing the land for miles. The trees were thickly gloved and weighted down with white, the church tower a black shape against a pewter sky. The silence almost bruised his ears. He had moved his lips, made a sound, just to check his voice still worked.

God he felt weary. He wound down the window further and the birdsong bubbled in from the hedges and the treetops. He caught a rich and dank smell of leaf mould.

He had thought that the bustle and excitement of Nicky’s wedding would bring some kind of change, flick the tracks and send them into a project they would tackle together. But he’d been firmly demoted to carrying out orders, mostly to do with opening the chequebook.

It was only a year ago that Nicky had turned up at Fourwinds with Sarah and announced the engagement. They had met the girl a few times before, but even so, it was hard to suppress a pause of evident surprise before jumping up to hug the children and say how thrilled they were.

Of course, Nicky hadn’t got as far as thinking about an actual ring. Alice said that he should let Nicky have the Colchester family ring. Ralph had fetched it from its hiding place. It was still in the small red box with the name of the jeweller imprinted in faded gold letters, the velvet inside fragile and silky.

The young couple had loved the idea of keeping a piece of family history alive, passing it down the generations. His mother’s engagement ring from his father now semaphored tiny flashes from Sarah’s finger. He’d watched her moving her hand to set the little colours flaring up in the light.

He’d almost blurted something out. ‘Thing about that ring is . . .’ genial, laughing a little. But he’d remained silent.

Hard to comprehend now, the way that sort of thing stained the fabric of a life, how it could seep through the layers and leave an odour trailing – make you seem worthy of suspicion and questionable. That was simply how things were, all those years ago. And it was too hard now, to crack open the silence and let the little lies spill out, pale misshapen things, grown into their confined spaces.

As a child, the weight of carrying his mother’s half-understood, necessary little untruths had always left him exhausted. ‘Two wrongs don’t make a right, Ralph.’ That’s what Mama had always taught him, her face serious and sincere, her soft hands pressing his cheeks.

He started up the car. The house on top of the hill felt miles away. Everyone remote in their all-consuming business. Everyone happy. And that’s how he should leave it. But the sense of unease refused to leave him.

He had the oddest feeling that Nicky’s Sarah had picked up on something, as if she had rumbled him in some way. What a funny little thing she was, sweetness itself, but there were moments when she could be quite fierce. She flinched away from any hugs. Looked at him sideways. He could think of nothing he had done to merit such a reaction, and yet there it was, slight but perceptible; she didn’t trust him.

The car arrived at the end of the drive, the afternoon sun deepening the colours of the bricks as Fourwinds came into view, the cedars in front stirring in the wind. Home. He felt a twist of longing for the place, as if he were already gone.

Alone in the guest bedroom Sarah had that thing you get in other people’s places; she was hungry but she didn’t feel she could waltz into the cavernous kitchen, rummage through their bread bin and get the butter from the fridge. Her stomach turned over, tight and empty. But then she never felt like herself at Nicky’s parents’. The house was pervaded by a faint smell of wood ash and old polish, and a breezy tone from the air that circulated through the tall sash frames, sometimes making them thump when the wind got up. She wished Nicky were there, his old denim shirt against her cheek, and she’d be fine again. His brother had organised the stag do and had kept the location secret. Knowing Mark, they’d probably be in Scotland, shooting something. They’d even taken her brother Charlie with them, looking like a hostage as they drove off in the car.

Sarah and her parents had driven over from Birmingham to help with various tasks before the wedding, although really there was little left to do according to the schedule on the kitchen wall downstairs. She moved to the bedroom window. The Colchesters’ house was famous for its views. Standing on the brow of the hill at the edge of the village, the house with its gracious symmetry looked out over miles of fields and the intermittent shine of the Dove River, the wind stirring the trees into constant motion.

Behind the house was the bulwark of the medieval church. On Sunday mornings there was an incredible noise from the bells, like hammers in a foundry. The Colchesters seemed surprised when Sarah mentioned the din booming through the house.

She closed her eyes against the sun. They felt itchy and sore. For the past few nights she’d been afraid to fall asleep; lately sleep dragged her back into days she thought she’d forgotten, dredging them up again in dreams. She would wake in the dark, soaked in sweat, casting around for the light switch. In the morning it was gone, the room filled with the clear summer light. Nothing to do but let the memory fade.

She’d almost told Nicky once, tried to explain to him what had happened. What she’d done. But the words didn’t exist. She leaned her forehead against the window glass.

Down in the garden she could see the marquee and the men who’d spent all day raising it. In just over two days’ time she’d be married. Her stomach did a little flip again. She saw herself walking down the aisle of the village church. Heads turning, faces smiling. The insistent smell of freesias.

The evening before, the vicar at Nicky’s village church had been taken ill. Impossible to find a replacement at such short notice, Alice had said in dismay. But as a fellow man of the cloth Dad had been able to trawl through the Crockford’s directory and had come up with a solution, an old friend called Cyril.

‘You remember him, don’t you?’ Dad said, as he came into breakfast with the news that morning. ‘Canon Cyril now. Haven’t seen him for years.’

She’d nodded her head. Smiled at the good news. Then she’d realised that the milk in her coffee tasted oddly sour. A lingering smell of burned bacon fat in the room. She’d stood up to take the cup out to the sink, pour the coffee away discreetly, but halfway across the kitchen she’d heard a crash. She saw the cup in pieces on the floor, yellow coffee stains splashed across the hem of her jeans. She’d forgotten to keep holding it. She’d knelt down to clear up and had to let her head drop, feeling suddenly faint.

A few moments later, and it had cleared. The cup swept up, the floor wiped. The day slotted back into gear and moved on.

Now the men down in the garden were packing up for the day. She watched them slamming the van doors and driving away towards the village.

She slipped down the stairs and went out into the garden. The flagstones around the house were warm through her sandals. The hems of her jeans brushed the lawn as she went to peer inside the marquee.

Somebody else’s wedding. There were stacks of boards piled up on the crushed grass, ready to go down as the dance floor. And there was Nicky’s mum at the far end, talking to Alan, the caterer. Too late now to step back outside and remain unseen.

‘Sarah, darling.’ Alice waved her over. ‘Just in time. We have to make a decision.’ She opened the brochure at a photo of circular tables and gold chairs, a sea of flowers and gleaming glassware. ‘Do we think it’s too much to have the gold chairs after all? Alan says there’s a problem with the white. We’re going to be short. Do you think it’s too much? I think it will look rather smart.’ An anxious frown on Alice’s petite face, the fair perm and neat lipstick.

‘Yes.’

‘Too much, or you think it will work?’

A slight pause. The Colchesters spoke English, but it was a different English, the words weighted and given different values. No serviettes at the wedding. Napkins. The wrong answer could be tricky. In a way it was easier to simply think of all this stuff as belonging to Nicky’s mum, nothing to do with the real wedding, not really.

‘It will work.’

‘Marvellous. There’s your answer then, Alan. Sarah would like the gold chairs.’ She folded the brochure against her chest, smiling.

‘It’s you, Sarah dear, who matters. This wedding is your big day. We want everything to be right.’ Alice patted Sarah’s arm ruefully.

‘Of course, it’s our fault entirely for having so many guests to seat,’ she continued.

‘Two hundred and fifty,’ said Alan, nodding. ‘It is a big wedding.’

Sarah left the marquee and its sad odour of crushed grass. At the edge of the lawn was an old apple tree, grey bark with green moss on the weather side, luminous in the evening sun. A climbing rose had grown up and spread through the branches, simple and beautiful. A few weeks ago she had sat out here late in the evening with Nicky, a huge butter moon resting on the horizon, a white owl crossing the garden silent as a moth, Nicky’s arm solid round her shoulders. It had seemed impossible to be any happier; Nicky and his kisses the only thing that mattered as they sat alone, whispering in the dark. She longed to see his tall shape now, loping across the lawn towards her, that wide grin that made everything turn out right.

She walked over to the tree and took one of the blooms in her hand and sniffed in the sugary smell. A petal cool as skin.

What Sarah had wanted was to get up early on the morning of the wedding and pick a bunch of roses and orange blossom and lady’s mantle from the summer garden. Alice had smiled; actually she had laughed. She thought it was more suitable to order a proper bouquet from the florist’s, the kind of stiff and pointless floral arrangement that Sarah hated. To keep the peace she’d gone to the florist’s and picked out peach roses and cream freesias and baby’s breath.

They’d be left behind when she and Nicky left.

Mum had said Alice was right about the bouquet. Sarah could see that Mum and Dad felt, if anything, even less comfortable than she did about being here. But Fourwinds was so much more practical for a wedding, plenty of room for a marquee, as Alice had said, quashing any objections.

It was so kind of Alice. Her energy was limitless. None of this would have been possible if they’d tried to do it on Dad’s salary. It would have been a much smaller affair – sandwiches in the church hall.

And there was something else, something that wasn’t being explained to Sarah, an uncomfortable undercurrent to do with how her dad had known Alice Colchester in the past. Turned out that he’d been evacuated to Alice’s parents’ house briefly during the war. That was as much as Sarah knew. She would have liked to ask more, a lot more, but no opening was offered. But then anything to do with the war years and her parents’ childhood was only ever mentioned in snippets of information. It was maudlin to want to go back over those years. Asking for more might dredge up a fact here and there, but never resulted in a cohesive whole that you could really grasp and understand.

Sarah carefully detached a rose stem from the main shoot, leaving a trailing thread of bark. She picked another couple of pale roses, and then she broke off a few sprays of the orange blossom. The combined smell was delicate and clear. She began to walk back to the house. These would be the flowers that she would carry at another wedding, the one that she would hold in her head, just her and Nicky there, and everything else blanked out – even as he asked her to repeat the words. Thinking about that moment, her hands were sticky with sweat, the rose stems slipping and turning sideways, the thorns pricking. She put the flowers down on the bank at the side of the drive.

Ages before tea. Not tea, supper; that’s what it was called here.

She looked at the large house, the shadow of someone behind a window, a flickering shape that reappeared and then was gone. She turned away, taking instead the path round the back of the garage with the shingle roof. She headed towards the gate in the yew hedge and went through to the churchyard.

Here at the boundary with the fields someone had been burning old bouquets of flowers cleared from the graves. The ashes still smoked and a faded spray of silk blooms stuck out of the debris, the petals darkened with soot.

She carried on along the gravel path. In front of the church she paused. She slipped into the porch, pushed on the heavy oak door. The warmth of the afternoon had not registered in here, the air cool on her arms. She sat down in a pew at the back and tried to let the calm of the thick-walled building spread into her body, let the silence absorb and still the odd spinning feeling inside.

If anything, here in the church, she felt the worry rising. She took a laboured breath.

She should say something. That’s what she ought to do. She tried to imagine forming the words.

Sitting in the silent church she could feel a pain in her throat. Alarmed, she rubbed at the tight ache. The muscles felt constricted, her breathing shallow and short. She tried to make a noise, form a word in the air. Only a breathy sound came out.

But it was years since she’d had that trouble, all those months and months when she couldn’t say a thing, the panic of a painfully closing throat each time she’d tried to speak – afraid that her breathing would shut down completely. She’d spent a week in the children’s hospital, which had made it worse. The doctor gave her sedatives; she’d slept a lot. Then they’d gone away on a family camping holiday. The warm sun, the freedom to curl up and read, and when they came back they’d moved to a different place. The problem faded.

She stood up, her hand clutching the tightness in her throat. It simply couldn’t happen now. But all this past week she’d woken up, trapped in a slippage of time, the past raw and inescapable all over again, hot with guilt, dizzy with fear and relief that it was over.

And now this.

If she could just carry on walking along the lane, walking towards the wood, out in the open where there was less pressure.

Sarah’s father, Peter Donoghue, listened as the grandfather clock in the hallway sounded ten o’clock. He had been outside, called her in, looked everywhere in the Colchesters’ darkening garden and then walked up through the village, but there was no sign of her.

He and his wife Patricia had been more dismayed than worried. Sarah was known for her long, solitary walks; she would disappear for hours and come back red-cheeked and satisfied. But now supper had been eaten in embarrassed silence and cleared away. They had helped the Colchesters wash up, and still no sign of Sarah.

So he had taken the car out and driven around the surrounding lanes to see if he could spot her. Now they were standing in the kitchen, discussing whether they should phone the police – the awful moment when all imagined things begin to tip over into reality – when they heard the sound of the back door opening.

Sarah was slipping off her sandals among the wellingtons and boots lined up in the back porch. She looked shocked as they all crowded in through the door. There were two high points of colour on her cheeks.

‘Really, Sarah,’ began Patricia. ‘We waited for you. We were worried. And poor Alice who’s gone to so much trouble.’

‘Perhaps a small sorry would do it,’ said Alice. ‘One doesn’t like to see food wasted.’

Sarah’s lips moved, but she didn’t speak. Her eyes fixed on her father. He took her arm and studied her face.

‘Sarah, what’s the matter?’

‘Lost her voice,’ said Alice with a little laugh.

Tears began to run down Sarah’s cheeks.

‘Oh no,’ said Patricia. ‘Sarah, is it that? Your voice? But it went on for weeks last time. Listen, darling, you can write things down, can’t you? Till it gets better. That’s all right to do, isn’t it, when you’re getting married?’

‘This has happened before?’ asked Alice.

‘But it was years ago. When she was small. Never since.’

They steered Sarah back into the sitting room. A scent of cold wood ash from the fireplace. Ralph unstoppered a bottle of whisky. Poured a dram and gave it to Sarah, but she shook her head and pushed it gently back towards him.

‘Never mind, old thing. I expect by tomorrow you’ll be your old self, singing at the top of your lungs.’

‘How long did you say it went on the last time it happened?’ murmured Alice.

‘It was several weeks. Then it just disappeared of its own accord, didn’t it? Oh Sarah, it’s probably just nerves, dear.’

Alice fetched paper and a biro from the writing desk. ‘There we go,’ her tone cheerful and calming. ‘Now you can tell us whatever you’d like us to do, dear. It’s not the end of the world after all. Just one of those things. Too much happening.’

She nodded encouragingly as Sarah wrote on the paper in swift block capitals.

Alice took the paper, paused. Her mouth slack, she checked the words over a couple of times.

‘No wedding. It says “no wedding”.’

‘Sarah . . .’ Patricia moved to fold Sarah in her arms, but Sarah brushed her off and stood up. She began pulling at her left hand. With a small, hollow clatter she let the ring drop onto the desk: three brilliant cut diamonds, cold under the electric light.

CHAPTER 2

Valencia, 1931

Eight-year-old Ralph Colchester sat in the sun on the kitchen steps next to a box of oranges, peeling and eating them one by one, and trying hard not to get his white shorts and shirt dirtied. None of the maids came out to stop him.

He was thirsty after a hot, stuffy siesta. Solid and full of energy and little boy muscles, it was torture to lie still and wide awake for what seemed like hours, nothing to do but look up at the slatted shutters closing out the garden and listen to the sound of cicadas. He was sure the maid had forgotten to tell him it was over. It was a relief to be out in the sun now, working his way through the fruit, the juice starting to sting the skin round his mouth. He saw Mama coming through the courtyard garden and hastily put a half-opened orange back on top of the box, then rubbed his hands on the sides of his shorts.

She seemed so small beside the fountains of palm trees. She was wearing her going-out hat, like a soft bell shading her eyes.

She sat down on the step beside him. Taking a comb from her bag, she parted his hair to one side. Then they went through the big hallway that ran through the middle of the cool house. She opened the door onto the glare of the streets of Valencia and they walked down the boulevard of calle San Vicente.

The Café de Paris was a big room with rows of small tables across a shiny floor. Mr Gardiner was alone at one of the marble tables, drinking coffee and a large amber brandy. A background of voices echoed off the green tiles on the walls. The ceiling fans high overhead added their clicking whirr. There was a scent of chicory and cigars. Mr Gardiner ordered him a cup of hot chocolate and a long fried pastry to dip in it, even though Ralph wasn’t very hungry. Mama tied a big starched napkin round his neck and watched him, both her hands holding on to the bag in her lap.

She opened the bag and took out a letter, handed it to Mr Gardiner. He leaned away and studied it, looked it up and down two or three times.

‘He’s divorced me,’ she whispered, glancing at Ralph, who pretended not to hear. ‘He’s got a divorce in Chile. He says he’s got a new wife. Can he do that?’

‘He can in Chile, evidently,’ said Mr Gardiner. ‘Extraordinary thing to do.’

‘I’ve nothing. He’s stopped sending anything back for months now, nothing, and then this.’ Mama began crying quietly and sadly.

‘Shh, shh,’ said Mr Gardiner. ‘Come on now, old thing. Chin up. You know you’re not alone. Silly Mummy, eh Ralph?’

Ralph nodded hard, Mr Gardiner and he restoring the world to rights again for dear Mama. Mr Gardiner was drumming the fingers of his left hand on the table. He held up the other hand to get the bill.

‘Aren’t we meeting up with everyone for a picnic, old thing?’

She sniffed and made an effort to rally herself, and got out her small mirror to check her face, then they went out into the hot street to find Mr Gardiner’s car for the drive to the river.

‘Come on, old Ferdie,’ Mr Gardiner said, holding the door of the Austin open so Ralph could jump in the back.

He had an English name and a Spanish name, Ralph Ferdinand Colchester. He was born in Valencia, but Mama said he was English, because his father and she were English. He didn’t know what his father had to say about it since, a couple of years ago, his father had had to leave them in Spain and go away to build railway bridges through the wild parts of South America. He had been away so long that he had forgotten to send them any money, and Mama had been forced to take a job looking after dear Mr Gardiner’s house. Ever since Ralph could remember Max had been there in the background at picnics and parties with the other English expatriates. And then Papa was gone, and Max had come up with his offer to help Mama.

And now Ralph could play in the gardens and the orange orchard, and talk with the Spanish maids in the kitchens at Mr Gardiner’s house, but he was not to disturb Mr Gardiner. Although the truth was that Mr Gardiner didn’t mind being disturbed a bit, it seemed to Ralph, and let him come into his office where the spidery pot plants crisscrossed the light slanting in through the Venetian blinds. He liked Mr Gardiner’s silly jokes and funny faces that were just for him, and he liked the heavy smell of cigar tobacco that soaked into the fabric of the room. Mr Gardiner bought Ralph tin train sets with clip together tracks from the city shops, and once a wooden boat that he helped him sail at one of the summer picnics in the Valencian parks, picnics where Freddie Marchington or someone from the British Embassy crowd always brought along a gramophone, and someone’s maid brought baskets of food, and there was always fizzy champagne and little bottles of cola in a bucket of melting ice. The grown-ups were sunny and giggly and had time to play with him while Mama, with her soft straw hat shading her eyes, sat up straight at the edge of the picnic rug, cutting Manchego cheese into neat squares and arranging them on a plate from the hamper.

Tippy Marchington, with her smudgy red lips, would be lying across the rug with her head on someone’s leg, telling stories about people, and making the others put their hands over their mouths and say, ‘No, I can’t believe that,’ or shriek with laughter. But Mama always looked sensible with her serene half-smile; much more good and lovely than Tippy with her blotchy face, especially when Tippy began crying – only because she had been drinking wine all afternoon, Mama said to him later.

When they got to the park Tippy was already there, holding court. Mr Gardiner flopped down on the grass and placed his panama across his eyes. Mama folded herself neatly at the edge of the rug, tucking the hem of her dress round her legs. Tippy had a man’s booming voice and a cigarette in a holder. She was actually drinking from the wine bottle, as a joke. ‘So I had to let her go,’ Tippy was saying to them. ‘What else could I do? Maids from the country are so silly. I told her when he started to call for her that she should drop that man. I could see he was married. You can smell it, but she just wanted to let herself be sweet-talked. She swore she’d dropped him but I could tell whenever she was going to see him because she’d be all red in the face and fired up and cross. Honestly, can you imagine? And now she’s as big as a watermelon, and I can’t have the shame in the house. He’ll never marry her. And she was so good with needlework. Her poor little bastardo.’

Later, as Mama was helping pack away the picnic, Ralph asked her what a bastardo was. Mama said no, she didn’t think it might be a type of mule in the villages. She wasn’t sure, but it was a common sort of word, not nice. He should never say it again.

Sometimes they all went out in the cars for the drive to the beach, the wind blowing into Ralph’s eyes. He’d turn round and kneel up, looking through flickering strands of hair as the wind blew it into tangles, and the legendary road disappeared behind them, the small donkeys and roadside villages retreating into the past. He liked to imagine stories; his best one was how he would see his papa one day, see him walking along the road, and they would stop the car, and then his papa would jump in and say how he had been looking everywhere, looking everywhere for him and Mama.

After a day of being dazed by the beach and the sun and the wind they would make the journey home, and he would go to sleep in the back of Mr Gardiner’s big car as they drove through miles of empty coastland. He’d hear the murmur of Mr Gardiner’s voice, and Mama’s voice, and the long note of the engine as if it were waiting to begin a song and then Mama would be lifting him out with Mr Gardiner’s help and he would wake up in his room next morning.

There was a photo on Mr Gardiner’s desk of a lady in a straw hat. By her side were a boy and two little girls, in a garden full of roses. For a long time Ralph had thought it was a photo of him, at some picnic he had forgotten. But when he asked Mama she said, ‘Don’t be silly, dear. All little boys look the same. That’s Mr Gardiner’s little boy who lives in England with his mama and sisters.’

He wanted to know all about the boy. Mr Gardiner said he went to a school in England – because an English education made you a gentleman. Mr Gardiner looked very lonely when he looked at the photo.

Looking at the picture gave Ralph a funny feeling, that somewhere, far away in England, there might be another Ralph, with two sisters, who went to a school for proper English gentlemen.

CHAPTER 3

London, 1932

Ralph had lived on a big boat for two days, and now he was a long way from Mr Gardiner’s house in calle San Vicente. He was standing at a window with a yellowy net curtain, watching the traffic go by in Westbourne Grove. They had been in this house for a week. It was cold, and outside it was foggy and when you walked along the pavements it was hard to see anything till it loomed up in front of you out of the mist. He wondered when they would go back. He missed Mr Gardiner.

Mama came into his room and took his hand. She was dressed in black, because Papa had died, a brave and good man, working hard to bring the railroad all the way to Chile. Ralph understood perfectly well that he would never see Papa now, and he knew it was silly, but he worried that when his papa returned to Valencia he wouldn’t know how to find them.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!