Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Eye Classics

- Sprache: Englisch

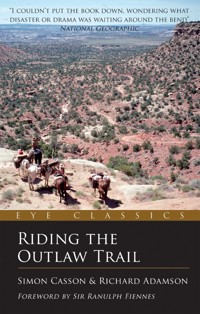

Inspired by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Simon Casson and Richard Adamson follow on horseback the trail of their boyhood heroes. They ride 2,000 miles through America's toughest and most treacherous terrain, crossing deserts, mountains, canyons and the high-plains of the 'Old West'. They have to endure harsh conditions and cope with natural hazards and in so doing bring the exciting and violent lives of the Wild Bunch vividly to life. This dramatic, inspiring adventure provides an insight into America's past and present.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 492

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR RIDING THE OUTLAW TRAIL

“A record of a courageous quest – absolutely gripping”

Daily Mail

“The account of duplicating Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid makes a bumptious and entertaining adventure story. Not Paul Newman and Robert Redford but wonderful chroniclers of the sights, sounds and feelings of that grand, harsh country.”

Time Magazine

“A fast read, a compelling story”

The New Mexico Magazine (USA)

“A glorious story, part adventure, part history, full of marvellous characters and amusing episodes. An outstanding book. Highly recommended.”

Douglas Preston, author of Cities of Gold

“An interesting read. One heck of a ride, an accomplishment – it made me think more of what Butch went through.”

Bill Betenson, great-great nephew of Butch Cassidy

“An intriguing adventure that Butch and Sundance fans will surely enjoy.”

Richard Patterson, author of Butch Cassidy – A Biography

“A fast-paced read into the history of Butch and Sundance. Experience unforgiving wilderness, along with the challenges of mounting such an epic.”

Richard Dunwoody MBE

“A delightfully revealing mix of candour and humour – a first-rate read of a frequently treacherous trek.”

Journal of the Western Outlaw-Lawman Association (USA)

“A highly enjoyable read”

Kirkus Reviews UK

“What a trip! What a story!”

Anne Meadows, author of Digging Up Butch & Sundance

“Everyone loves Butch and Sundance, many would like to emulate their adventures, but only these guys have done so. I’m envious – it makes good reading.”

Nick Middleton, explorer and TV presenter

“An epic and impressive undertaking”

Hugh Thomson, writer, film-maker, adventurer

“A fun read and an interesting commentary on the hardships of outlaws on the run.”

Donna B. Ernst, great grandniece of The Sundance Kid

“One hell of a tough expedition; one hell of an exciting story.”

Gary Ziegler, explorer

“A great adventure story – full of intrigue”

Horse Magazine

“The book is a pleasure – unputdownable!”

Local Rider Magazine

“An enjoyable read”

Western Outlaw Lawman Association Gazette (USA)

“Entertaining”

Outlaw Trail History Association & Centre Journal (USA)

“A modern day adventure… the legend is brought alive through Simon and Richard’s epic ride”

Western Rider UK

“An easy read – amusing and graphic!”

Western Equestrian Society

“Vivid detail and desciption – a triumph of endurance and persistence”

The American Quarter Horse Association, UK

“A cracking read, packed full of adventure and drama”

Wanderlust

This Eye Classics edition first published in Great Britain in 2011, by:

Eye Books

29 Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

First published in Great Britain in 2004

Copyright © Simon Casson and Richard Adamson

Cover design by Emily Atkins/Jim Shannon

Text layout by Helen Steer

The moral right of the Author to be identified as the author of the work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The paperback edition of this book is printed in Poland.

ISBN: 978-1-903070-65-9

To Butch & Sundance for existing, Richard Adamson for his excellent leadership, A.C. Ekker for starting this grand adventure and Gene Vieh for making THE connection…

RICHARD ADAMSON

Sadly, whilst heading operations for security company ArmorGroup, Richard was murdered in a robbery in Kabul, Afghanistan on August 16, 2007. Richard’s CV would make James Bond envious. Tasked by Margaret Thatcher to lead secret teams training Afghans in the use of stinger missiles, (credited in turning the course of the war against the Russians), he returned to Kabul in 2001. Richard opened ex-pat bar Elbow Room and took a partnership in Samarkand, a club. His working knowledge of the people, culture and languages was vital. He was recognized as a true friend of Afghanistan.

A.C. EKKER

A.C. personified the American cowboy. He knew the Robbers Roost country like the back of his hand. His grandparents homesteaded the famous ranch over a century ago – great grandfather was Charlie Gibbons, friend and employer of Butch Cassidy, who hid out at the Roost and did business with Gibbons at his store in Hanksville. Tragically, on November 17, 2000, A.C. died crashing his plane searching for stray cattle on the final round-up. In the toughest tradition of the Old West, he died with his boots on.

GENE VIEH

A big ‘tip of the hat’ to Gene, who passed in April 2008, he was instrumental in connecting me to his cousin Dr Joe Armstrong, who assisted the Swedes in the attempt to ride the trail. Without that connection and knowledge brought, our quest would have been higher risk, with stronger likelihood of failure. Gene introduced me to many ranchers, land-owners and families that were supportive of our challenge.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY SIR RANULPH FIENNES

A NOTE TO THE READER

A HUNDRED YEARS TOO LATE

WILD BUNCH VERSUS SUPER-POSSE

OUTFITTING THE OUTFIT

BREAK FROM THE BORDER

STAND-OFF AT OUTLAW CANYON

UNDER THE TONTO RIM

THE BLUE WILDERNESS

BEHOLD: A PALE HORSE

SHOWDOWN AT MEXICAN HAT

ROBBERS ROOST

DEATH OF A LADY

RIDING THE HIGH COUNTRY

THE OUTLAW STRIP & BROWN’S PARK

A STING IN THE TAIL

QUIÉN SABE?

HOLE-IN-THE-WALL

THE BIGHORNS

LICKING THE TONGUE

BADLANDS & MISSOURI BREAKS

LAST OF THE BANDIT RIDERS

EPILOGUE

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

“Riders who passed along that trail were men of iron, accustomed to the roughest sort of life, able to ride all day and night without rest over dry deserts and through dangerous canyons. When required, endurance and courage were paramount – those who lacked either were quickly eliminated.”

Charles Kelly

The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch. New York, 1959

April 17, 1990

FOREWORD

To ride the length of America on horseback is a reasonably serious business. But why do it the hard way: across vast deserts, mountains, and high plains wilderness, at the height of a hot, dry Western summer and without back-up?

A century ago it could only have been to evade the law, remain at liberty and enjoy ill-gotten gains, which is presumably what motivated the outlaws of the Old West.

But to face all the same hazards and hardships when you don’t have to, as Simon Casson and Richard Adamson did, can only be because – despite being men in their middle years – they were driven by an irresistible spirit of adventure, a laudable condition in a material age.

They had a tough trip, and they write with candour and humour about their moments of frustration, fear, exhaustion, self-indulgence and deep satisfaction. They learned a lot about horseback expeditions, but even more about themselves.

After reading their gripping account you may well find yourself digging out and dusting off your own long-forgotten dream of adventure. If so I hope you will go for it, as they did.

A NOTE TO THE READER

No one who relished every second of George Roy Hill’s brilliant and now cult 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid can be surprised to learn that the real life Butch and Sundance made a lasting impression on everyone they met. Leaving no diaries or personal accounts, they wrote few letters, but managed to write themselves handsomely into the history books and the legends – and they are still writing.

We know that Robert LeRoy Parker, alias Butch Cassidy, and Harry Alonzo Longabaugh, the Sundance Kid, were something special. Both were respected by most who knew them, and had been born to caring families in the West and East respectively.

Both were restless youths who left home early, eventually meeting to discover a shared love of adventure and a cheerful disregard for the law.

All written and oral records confirm that talented screenwriter William Goldman and megastar actors Paul Newman and Robert Redford got the basic characters just about right: Butch was affable, good-humoured and intelligent while Sundance, warier but still friendly, was the quieter of the two – though he liked sharp suits and monogrammed clothing. Both were criminals rather than killers. Indeed some historians believe that right up to the final shoot-out in Bolivia neither Butch nor Sundance had blood on their hands. If true this is likely to have been a matter of sheer efficiency rather than conscience – for years they were clearly happy to ride and rob with some very desperate and bloody men.

What is certainly true is that Butch and Sundance were consummate professionals at their craft, undoubtedly the best in their business in every way: longer active careers, more sophisticated planning, higher success rates, less prison time and greater financial returns for a given investment of risk. However, as law enforcement entered the telegraph age and the frontier finally closed in 1900, they were smart enough to know the game was up. They moved to South America and tried to go straight. Sadly, their best-laid plans didn’t quite work out.

But this book concentrates on their travels and exploits in the American West. It describes a daunting – maybe insane would be a better word – journey by two Englishmen who followed the Outlaw Trail on horseback across two thousand miles of desert, mountain, canyon and high plains wilderness, from Mexico to Canada via New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

With 20-20 hindsight it is remarkable if not ridiculous that we undertook this demanding trip with no previous experience of long distance riding or horse-packing. We were absolutely determined to study at first hand the most physically challenging – and in research terms the most neglected – aspects of a hard, violent but heroic, action-packed era. We would ride, as nearly as possible exactly as they did, the almost inaccessible trails that linked the robberies, escapes and hideouts of the two most elusive and successful outlaws of the Wild West.

Where we went and what we experienced we have recorded faithfully and placed in their proper (and sometimes improper) historical context, which in turn is as accurate as five years careful prior research could make it. As well as our adventures and the many colourful characters we met, we have described baldly the life-threatening hazards, hopes and fears, tensions and often angry dissentions and confrontations of riding the Outlaw Trail, whether then or now.

Enjoy the read.

Simon Casson

&

Richard Adamson

A HUNDRED YEARS TOO LATE

“I got vision and the rest of the world wears bifocals.”

BUTCH CASSIDY

SIMON:

The classic blockbuster ‘buddy’ movie almost certainly ensured that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid will remain immortal. Remember the second train-robbing sequence which opens with Sundance moving cat-like along the tops of the swaying carriages just prior to the holdup? At its climax is a cataclysmic dynamite explosion when half the railroad car is blown sky high and thousands of dollar bills come fluttering down out of the sky through the still quivering air. The gang’s instinctive reaction to this unplanned development is to dart about, greedily gathering up the falling greenbacks like manna from heaven.

Then we see another, much shorter train approach and stop very close by. A brief pause for surprise and speculation, then a whistle blows, a huge wooden ramp crashes down and out of the sinister train rides the handpicked ‘Super-Posse’, armed to the teeth and led by legendary lawman Joe Lefors in his trademark straw boater. Newman, as Butch, says urgently:

“Whatever they’re selling, I don’t want it.”

But I did.

Family history gave me the perfect excuse to pursue my love affair with the West. My father’s family is connected with Stonewall Jackson, the famous Civil War Confederate General. My mother’s is connected with James Wolfe, hero of Quebec – of whom King George II famously said, “If Wolfe is mad, I wish he would bite some other of my Generals.” When I was young, this somehow didn’t seem quite as glamorous as Butch and Sundance’s bloodlines, but it was close.

From the age of six I did, of course, possess a cowboy outfit complete with hat, chaps, boots, neckerchief and six-guns, and I ran wild in the neighbourhood chasing imaginary Indians and pop-popping my guns.

But the story of our ride really began quite unconsciously in a secondhand bookshop when I first laid hands on a copy of Robert Redford’s Outlaw Trail. Glossy pictures and a fast-reading script sold me on the quest of one of Hollywood’s finest to seek the Outlaw Trail and learn about the Sundance Kid. I forked out my last seven quid and departed. It was a great read, but the subject matter then remained dormant until the summer of 1994.

We were vacationing in Arizona. The Grand Canyon was awesome and Monument Valley spellbinding. Tombstone, billed as ‘the town too tough to die,’ ignited the real flame of interest. Whose imagination would not run wild on the stomping ground of the legendary Wyatt Earp, his brothers and their deadly dentist friend Doc Holliday? As we walked through the OK Corral, my partner Julie suddenly announced her ideal holiday for next year: a Western dude ranch experience. A deal was struck there and then.

There was one problem. All the ranching brochures were offering soft adventure – I badly wanted risk, blended with history. That winter, on impulse, I tracked down the same people who had outfitted Robert Redford and National Geographic all those years before. In minutes, I was speaking to Glori Ekker, the wife of a highly regarded outfitter. I put the vital question:

“Do you still outfit horse trips in the Canyonlands?”

“Sure. AC operates maybe two a year. We’ll mail you information.”

Their brochure promised a fascinating trip, and I made arrangements for a five-day ride in mid-September. It was as easy as that.

So September found us driving deep into southeast Utah to a remote outpost called Hanksville, little changed from Redford’s descriptions.

The gas station still functioned in the town centre. Opposite, a restaurant-campsite was the jump-off for tourists heading for Lake Powell. Our hotel, The Whispering Sands, even had a pet bison.

I rang the Ekkers, left a message and sat back to wait for the rendezvous. The phone woke us from slumber at six the next morning, and AC announced he would collect us within the hour. Sure enough, a huge truck, all V8 muscle, drove up and shut down, and out stepped AC. Medium height, swarthy, late forties, decked out in rodeo Wranglers and the mandatory weather-beaten black Stetson, he wore a toothpick in the corner of his mouth. The quintessential cowboy. Grinning, he shook hands firmly.

There were just the three of us. We trailer-hauled the horses sixty-five miles across remote country. There were no signposts or phone boxes, no anything, just a red, dusty track leading to the infamous Robbers Roost. If you broke down here, you were dead. Two hours later, the old stucco ranch hove into view. I recognised the tack store and weathered corrals shown in Redford’s book. It was heartening to find little had altered. The ancient bunkhouse was still there too. Gnarled cedars were split and twisted by the brutal elements. Time seemed to have stood still around here since 1909.

We saddled up and headed off into Utah’s forbidding canyon country to find the West that was. It was challenging riding. We rode our horses into places you would never think possible. Butch and Sundance had undoubtedly been the boldest (and smartest) of outlaws to ride into this beautiful but broken and hostile country, with its untamed myriad of interlocking red rock canyons, pinnacles, spires and mesas shrouding secret caverns, watering holes and grazing pastures.

AC generously shared his vast range of knowledge, history and anecdotes of the Roost whilst my camera struggled to capture the stunning scenery. It was awesome. Fabulously hot blue-sky days merged into bitterly cold nights, and the five days flew past. When it was time to leave, I was sad, but I had enjoyed my first taste of riding the trail, and I felt the early stirrings of an idea which was not yet fully formed.

Once home, I found myself becoming obsessed with those remarkable outlaw riders. I returned to America five times, travelling and researching Butch and Sundance just for fun, eventually clocking up an incredible 15,000 miles. During autumn 1996, I learned that two Swedes had ridden much of the Outlaw Trail, from Las Cruces, New Mexico to Miles City, Montana. It was a tough ride, but it didn’t go all the way. Rancher Gene Vieh informed me that his cousin Dr Joe Armstrong, an equine and agriculture professor from Las Cruces, had outfitted the Swedish duo four years earlier – a casual comment which later proved highly significant.

In between my American trips I consulted everyone I could think of in the UK who might be willing to give me the benefit of some straight talking from their own firsthand experience. I talked to blonde, blunt Ruth Taggart and her partner Nigel Harvey of British riding specialists Ride World Wide in London. I telephoned Robin Hanbury-Tenison OBE, FRGS, a renowned British explorer and long rider of four major equine expeditions. Robin said he had no useful contacts in America, but advised me to ring Dylan Winter, who had ridden the Oregon Trail. Later, I had a really valuable session with Dylan at his Buckinghamshire base. I contacted equine explorer James Greenwood, recently back from completing the arduous Argentina to Peru section of AF Tschiffely’s famous ride. I rang to congratulate him, and to glean advice.

To each of these experts, I outlined what somewhere along the line had crystallised into a firm objective: to be the first man to ride Butch Cassidy’s Outlaw Trail from Mexico to Canada on horseback. Without exception, they were friendly and helpful. Basically, however, they were all singing from the same hymn sheet, and between them they made me face up to some unwelcome realities.

First, they scared the shit out of me with their rough cost estimates for what I had in mind – they were talking telephone numbers, way beyond my reach. Then they pointed out politely but brutally that I had neither the expertise nor the resources to tackle the projected trip on my own. They also severely disillusioned me about the prospects for some easy sponsorship money. Finally, they urged me to find someone else who was also planning a horseback expedition, and try to persuade them to join forces. Bloody but unbowed, I continued to develop my plans; though I was no longer sure they would ever come to fruition.

I joined the English Westerners Society and the Outlaw Trail History Association through which I made contact with respected former Spokane journalist Jim Dullenty, responsible for monumental research on Butch Cassidy and now an Americana book dealer. He was a founding member of the Western Outlaw-Lawman History Association (WOLA) in America, which comprises key historians and writers, including leading authorities on Butch, Sundance and the Wild Bunch. This association also led me to the outlaws’ families and living descendants

I bought literally dozens of history books, whilst Jim provided added inspiration and contacts. He confirmed that nobody had authentically ridden the full length of the Outlaw Trail on horseback from Mexico to Canada. It would be a first – if I made it. I set about planning how to ride the trail, keeping one eye always on the possibility of spinning off a new business venture from all this present and projected effort.

To have real value, the project would have to replicate Butch and Sundance’s travels with precise historical accuracy. I spent hours poring over maps pinpointing the Outlaw Trail’s ghostly traces. It would be a massive task. I was no explorer or long distance rider, and certainly not a horse-packer, but I believed in myself. Others had misgivings, which I ignored. Riding a horse was like riding a bike, I told myself. Once done, you never forget how. The doubters and pessimists bluntly informed me I was out of shape, out of order and out of my mind. We would see.

I was getting more apprehensive by the day but continued to throw myself into the planning. Prudently, I wrote to ranchers and landowners for permission to cross their private land, so that my route could follow faithfully the faded trail from Mexico to Canada. I was greatly encouraged to receive a thumbs-up every time. These were kind folks, proud of their heritage, and it was clear that they really cared. They did, however, add to the mounting chorus of cautionary verses: did I really know what I was letting myself in for?

Oh yeah, of course I did. Well, sort of.

The fact is that Butch and Sundance had made some of the most demanding rides ever known, with the added pressure to outpace pursuit, avoid ambush and evade capture. The only way truly to understand their experiences and some of their risks was to share them, to travel the same barren desert and mountain country in exactly the same way: on horseback, with packhorses, carrying bare essentials only, finding grazing and water where and when I could and with no motorised back-up.

In those thinly populated regions, the Code of The West was important. It was the Westerner’s offer of assistance to anyone in need without denial or question. A civil traveller weary or lost might expect the offer of a meal and rest. In exchange, the traveller might offer to do ranch chores or contribute financially. In Butch and Sundance’s time, ranches were never locked and riders were welcome, provided they remained polite and respectful. If nobody was home, a long distance rider might well help himself, taking only what was needed for immediate use. If a man was afoot, he could procure a horse – later, he was expected to return it.

The spirit of that Code held true today, with the important addition that in an age of phones and emails, you were supposed to use them – or, better still, get your hosts to use them. Thus, a well-endorsed traveller can be passed like a parcel from household to household across the nation. So the outlaws and I would be riding the same trails in much the same conditions – apart from the fact that I was starting a hundred years too late.

I constantly debated with myself whether to continue or quit. Was it possible that so many respected authorities could be overly pessimistic? Or was it conceivable that, like Butch, I had vision and the rest of the world was wearing bifocals? Each time I confronted it (not more than ten times a day), the decision felt like twisting on nineteen when your option is to pay twenty-ones. Each time, I assessed the unattractive odds realistically. Then I twisted anyway.

Russian Ride was interesting. It told the story of a woman’s 2,500 mile trek across Russia with Cossack horses. I wrote to Barbara Whittome’s publisher seeking her ideas and help. Well, why not? So far these explorers had all proved to be both approachable and helpful. Weeks later, a reply indicated that Barbara was planning to ride across Europe.

On the phone she sounded bright, ever-so-English, confident, even slightly bossy – just a hint, perhaps, of the voice that lost us the Empire.

“Join me for a couple of weeks in Hungary. See what you’re in for. I’m selling places to help fund the ride. My Russian trip cost a fortune.”

Shrewd lady! I admired her approach, but I wasn’t buying.

“I’m interested, so let’s talk horses,” I replied.

We met, and discussions were fruitful. Barbara hoped that I might join and subsidise her trip. Similar thoughts were crossing my mind. We agreed to correspond. As time passed, zilch happened. My major concern was not to be pre-empted on the Butch and Sundance project. Barbara eventually rang to tell me her journey was off. I cheekily suggested that we should team up for my trip, and after some more chat she accepted. Success! I maybe couldn’t ride like these horseback explorers, but I hadn’t entirely lost my touch – my plan was gradually coming together.

In 1998, I spent a glorious three weeks in Texas, then snuck into La Mesa, New Mexico to meet the Armstrongs. Joe and Rusty confirmed their willingness to help, advise and outfit the expedition. Timing was set for spring 1999.

One snag: Barbara seemed to know her stuff, and I certainly knew mine, but neither of us was checked out on mountain and desert survival. Barbara suggested we invite Richard Adamson to join us. Richard was described as an ex-Royal Marine Commando with impeccable credentials, presently in East Africa. Despite being nervous about someone else coming on board, it sounded logical. Besides, the three of us would neatly replicate the movie trio: the new Butch Cassidy, Sundance Kid and Etta Place. I record it a bit red-faced, but that unbelievably soppy reasoning was probably the clincher. I agreed.

No hint came from Richard about whether or not he would accept our offer. The sands of time were dribbling away, and I got mighty nervous. I was committed, and I continued methodically with arrangements. I also wrote endless letters in search of sponsorship. As predicted, I failed, and we were forced to self-fund. Groan! I even invited Robert Redford to join us. Politely, or wisely, he declined the offer.

Redford had waxed lyrical: “The Outlaw Trail fascinated me – a geographical anchor in Western folklore. Whether real or imagined, it was a phrase that for me held a kind of magic, a freedom, a mystery.”

I knew it was real and I was ready to endure, a century after Butch and Sundance were at their peak and thirty years since the runaway success of the Hill and Goldman movie. And I would complete the mission playing strictly by my self-imposed rules. My main reward would be to get a unique gut-feel for the outlaw way of life, but I would also be retaking control of my own life. Freed of petty restrictions, I would become an accomplished horseman and I would ride back into the past, Winchester strapped to my saddle, determining the distinction between right and wrong and making my choices. Heady stuff.

Meanwhile, for months Richard had ignored all letters, emails, phone calls and messages. It seemed he would not be joining us. Then, at the eleventh hour, Barbara rang to tell me Richard had arrived unannounced for formalities and dinner in London. So I finally shook hands with a raw-boned, silver-haired, tanned and supremely fit ex-Marine Commando who had been permanently delayed in Somalia since October 1998.

RICHARD:

I had been working in Nairobi helping to set up an aviation service for the European Community Humanitarian Office. After establishing outstations in Kenya, Somalia and Djibouti I moved my base to Hargeysa in northern Somalia, as General Manager of Airbridge. This was a small regional airline, which we set up in partnership with Candy Logistics, and in which quite a lot of Somali money was invested.

I was aboard our plane minding my own business (which at that precise moment was to get the aircraft back to its native Ukraine for re-certification). Just prior to take-off, armed Somalis came on board, and the plane was commandeered and grounded. Along with the Ukrainian crew I was abruptly taken hostage at gunpoint.

It was fairly dramatic, and I had visions of a Keenan/McCarthy type incarceration in a dungeon, but within twenty-four hours I was allowed to take up residence in a Government hotel, albeit still under house arrest. It turned out that the Somali investors, dissatisfied with the progress made, were demanding the immediate return of their substantial investment. They had me snatched just in case I was doing a flit with all their loot. Chance would be a fine thing.

They then attempted to give their entirely improper behaviour some slight whiff of legality by bringing a civil action against Airbridge and me in the Courts, claiming that the contracts signed by both parties were not in fact contracts.

Farcical court procedures ensued which went on for two months. First the Regional Court found in our favour, then the Court of Appeal found against us, then the High Court of Appeal ruled. During this time Barbara persuaded me to join the Outlaw Trail expedition. I had no idea if and when I was going to be released.

Whilst Simon was trying to contact me, I was requesting meetings with the President of Somalia. We had met on many occasions, and he knew of my plight. He asked what he could do, since court procedure was slow, biased and expensive. I requested arbitration.

A committee was formed, but mysteriously all the members turned out to be related in some way to the plaintiffs, so it was no surprise whatsoever when they ruled our contract null and void. Airbridge was required to return 50% of the funding, plus six months running costs of the complete operation. Thus, my freedom cost $600,000. I left Hargeysa rapidly and spent Christmas and part of January in Zanzibar scuba diving with my sons Ben and Jamie.

I met Simon in London a month later and we had four hours together. I wasn’t that impressed, and had reservations about our compatibility, but I was already committed. Ours was not a partnership based on prior knowledge and shared experience – it was a completely unknown quantity. On paper, we possessed the relevant and complementary skills for such an expedition, but we were very different people.

I’d spent many years in the Royal Marines, Barbara had been a lecturer and Simon was a dodgy ex-used car salesman with a bee in his bonnet. Barbara would manage the horses, Simon would be responsible for contacts, PR, photography and the historical side, and I would handle the logistics and assume ground leadership.

After dinner, I wanted to map out the expedition in detail. I provided six state maps. Decent topographical US Government Survey maps, I was assured, could easily be procured on arrival. Next, we discussed the trail. We were to traverse a strip of land nearly two-thirds the length of Chile and seemingly less than three-tenths of a mile wide. The first thousand miles were a vast desert. Water sources were scarce: springs, streams and cattle troughs. Depending how deep we rode into the Gila and Blue Wildernesses, there was also tricky mountain country to negotiate.

What concerned me most was the Canyonlands district in southeast Utah. The section we would be riding through was 527 square miles of pure wilderness. In the time of Butch and Sundance, it was inaccessible and seldom visited by the law; nothing much had changed. Beyond that, we had to negotiate the San Rafael Desert and the little-known Book Cliffs country. I predicted the maps would be devoid of markings, which always denotes a harsh, arid and trackless landscape. And we were thinking of riding horses through it.

Over coffee, we calculated the distance. Two thousand miles. Barbara estimated we could cover an easy twenty miles a day and the trip would take just over three months. Simon agreed. I was more cautious and measured the trail again. Then I suggested we think of scouting the lower end of the trail from Silver City south to the Mexican border. Simon protested there was no time.

“No. We’ll have to ride like the outlaws and make out,” he said, adding that, “this was no truck-and trailer-backed expedition.”

“What about pre-dumping feed and supplies?” I asked.

Simon shook his head again.

“No way. This has to be unsupported. If we do it any other way, it’s cheating. We’ve got to do it just as Butch and Sundance did – with packhorses, and whatever impromptu help is forthcoming from sympathetic locals.”

The planned route Simon showed me would take us across six States, six Indian reservations, three National Forests, two Wildlife Refuges, a Primitive Wilderness area, a National Recreation area and a National Park. Not forgetting the deserts, of which I counted five. At least Simon had already written to friendly ranchers and outfitters checking on permission to access land.

“Now what about the authorities?” I asked. Simon deftly brushed the question aside:

“Joe’s looked into all that. My contacts should be able to negotiate and advise on permits. If refused access we’re in trouble, but we’ve still got to ride through whatever.”

Simon seemed very positive, or was he just intending to wing it? We discussed private land issues. Again, it was impossible to discover who owned what. We would ride through regardless. If and when problems arose, I had already decided to rely on Simon’s silver-tongued bullshit to extricate us.

SIMON:

My last day in the rat race was 6 April 1999. I wondered if I would disappear permanently into the jaws of obscurity, or only momentarily. Commissioned to write a report for the Travel Trade Gazette, I hoped to be successful and have some interesting tales to tell.

One difficult duty remained: saying goodbye to my mother who was valiantly losing a seven year battle against cancer. Our hopes were to reunite on my return. Before leaving, I fought the demons, and during the goodbyes my sixth sense told me it might be the last time. I momentarily froze when Mum bade me good luck and instructed me to finish the ride whatever. That was the last time we saw one another. I stepped into the clear night. Our party was departing tomorrow – early.

My farewell to my father was again very difficult. We bear-hugged. Ill with worry, I fought back the tears. It was also to be the last evening with my patient, loving girlfriend Sharon for over five months.

RICHARD:

Simon seemed unusually quiet at the airport, while I found I had no worries. I had brightened at the prospect of the challenge. After the kidnap episode, I was off on another exploit and eager for it.

There was little luggage when we met at London Gatwick as I had kept an open mind on our requirements for the ride, intending to purchase most of the equipment in New Mexico. Obtaining goods on the dollar-to-pound ratio was advantageous, and also avoided paying enormous amounts in excess baggage, which would impinge on our slim budget.

As I sat back to quaff a coffee, the airport’s tannoy system blared my name, calling me back to the check-in. British Airways wanted to remove an item from my baggage. They were unhappy with my stove – it showed remnants of fuel and was immediately deemed hazardous cargo. I was forced to leave it behind and actually never saw it again. Bugger! And it had interrupted my Burger King breakfast. The world’s favourite airline lost some of its popularity. We had a few precious moments to say our last goodbyes, and then we lit out for a supreme adventure.

WILD BUNCH VERSUS SUPER-POSSE

“Who are those guys?”

BUTCH CASSIDY

SIMON:

The Wild Bunch was the largest, most dangerous, successful and organised outlaw gang in the history of the American West. They rode and robbed right up till 1912, when the last survivor Ben Kilpatrick was killed at Dryden, Texas in the last train hold-up conducted from horseback. When they died, the Old West died with them.

Today, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid are renowned as a part of Western lore, but in their time, they were not noticeably romantic. Though they had many sympathizers, they were bad men who were badly wanted. Sheriffs, posses, US Marshals, the Union Pacific Railroad, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, freelance bounty hunters – literally scores of people were desperate to find them. That included the popular writers, whose colourful reports of their doings right up to the present day have seldom been understated.

Though Butch and Sundance are long dead and buried, the historians, researchers, authors and filmmakers are still actively chasing their last known whereabouts. If they are looking down at us today, apart from deploring the lack of progress – still too much corporate power and too many customer-unfriendly railways – they-will surely be amused and gratified to be the objects of such interest. Painstaking research by dedicated historians has (mostly) separated myth from reality in the events of their lives, but many important questions still remain open.

What actually happened to Butch and Sundance? Did they really die in a shootout with the Bolivian cavalry, as depicted in the movie? Where are they buried? Did they return to America and assume new identities, as some relatives have claimed? Renowned historians continue to debate – sometimes hotly. Faint hopes still survive of some day unearthing their bones, thus providing the final solution to a great Western mystery.

And who named Butch and Sundance’s “Wild Bunch?” Various outlaw gangs operated in the southwest during the late nineteenth century. Perhaps the survivors, the “best of the rest,” evolved into a super-gang known as the Wild Bunch whose members came and went?

The “inner circle” were later labelled the Fort Worth Five. A famous picture taken in Fort Worth, Texas, in November 1900 by photographer John Swartz is now legendary. It shows Sundance, Ben Kilpatrick (the “Tall Texan”) and Butch Cassidy seated, while standing behind are Will Carver and Harvey (Kid Curry) Logan.

Swartz was impressed with these five handsome dudes in their Sunday best when they came to visit him. They had gone mobhanded into expensive local stores and purchased entire new outfits, down to spats and derbies (or as we would say, bowlers). Apparently, the outlaws were headquartering locally in a rooming house – said to be a brothel – in Fort Worth’s sporting district, where by day they rode bicycles and by night spent their gold recklessly on the resident “soiled doves.”

The finished picture was prominently displayed in Swartz’s studio window as a good advert for the business. It became the most famous photograph he took. It was also the gang’s biggest mistake. Before long, the major law enforcement agencies were fighting for copies of what was the first really reliable guide to the visual identification of the gallant but vain band. It was almost certainly the direct cause of their splitting up and going to meet their destinies by different routes.

Butch Cassidy is born Robert LeRoy Parker on April 13, 1866, in the town of Beaver, Utah, of Mormon parents. He is the eldest of thirteen children to Maximilian and Ann Gillies Parker. Butch’s origins are British. His namesake, his grandfather Robert Parker, born in Accrington, had been a weaver in Lancashire’s textile industry.

The Parker family emigrates, walks (pushing a handcart) west and south to Salt Lake City, Utah and eventually settles at Beaver. Butch’s parents meet and marry there in 1865. His father acquires a 160 acre property and a two-room cabin in Circleville, a small town comprising a few stores and a schoolhouse.

He first carries mail on horseback from Beaver to Panguitch through the rough, unsettled Circle Valley where Indians are a constant source of trouble. He also takes temporary employment with mining companies, and eventually buys a few head of cattle. It is a tough existence, and the winter of 1879 virtually wipes out the Parker herd, leading to legal disputes and an unjust settlement which impoverishes (and enrages!) the elder Parker.

Perhaps this unsuccessful family brush with authority has a lasting effect on young Robert. Now called Bob, he works for neighbouring farmer Jim Marshall, where he forms a solid friendship with a skilled livestock handler and horse wrangler named Mike Cassidy. Mike is everything Bob wants to be: tough, self-reliant, free as a bird, with itchy feet and sticky fingers. He uses the Marshall ranch as a cover for discreet rustling and mavericking, and it is virtually certain that Bob Parker drifts into crime under the Cassidy tutelage, perhaps leaving home (to his mother’s anguish) initially to deliver a bunch of stolen horses to the infamous and remote Robbers Roost in southeast Utah.

Butch, still known as Bob Parker, surfaces next at Telluride, Colorado; a staging post on the pipeline for stolen livestock. There he makes a new friend who has exactly the same background as himself: raised in Utah by a Mormon family, ran away from home, cowboy turned part-time petty rustler. Matt Warner (real name Willard Christianson) has a fine mare named Betsy, which he races on the Colorado circuit. Their paths cross, Bob matches his horse against Matt’s mare and loses, then the pair join forces and became partners in the horse business.

Later, Matt introduces Bob to his brother-in-law Tom McCarty. Tom and his own brother Bill operate near Nephi and Manti, Utah, stealing horses, cutting cattle out of herds and selling to whoever will overlook doctored brands in Telluride. Now the McCartys have a cabin near Cortez, Colorado, only a mile from where Harry Longabaugh (later the Sundance Kid) lives for a spell with his cousin. Through the Warner-McCarty family connection, the future Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid may well meet as early as 1885.

Bob pulls his first bank job on June 24, 1889. The San Miguel Valley Bank is robbed of $20,750 – a huge sum of money, enough to retire on. The culprits are listed as Bob Parker, Matt Warner and Tom McCarty. Newspaper reports suggest the three robbers are assisted by another unidentified accomplice:

“The robbery of the San Miguel Valley Bank of Telluride, on Monday by four daring cowboys… the four rode over to the bank, and leaving their horses in the charge of one of their number, two remained on the side walk and the fourth entered the bank.” Who was the fourth man? Some say it was the Sundance Kid.

The future Kid is born Harry Alonzo Longabaugh to Josiah and Annie Longabaugh in the spring of 1867, at Mont Clare, Philadelphia. Harry is the youngest of five children of a Baptist family which originated in Germany. Harry’s father Josiah marries Annie G. Place on August 11, 1855 in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania. Josiah is a farm laborer who is drafted for the Civil War and moves frequently. By early 1880, Harry is not living with his family but is listed as a servant boarding with Wilmer Ralston in West Vincent, Pennsylvania. Ralston farms just ten miles from Harry’s parents.

Harry reads the dime novels that take him West in search of adventure and joins his cousin George Longenbaugh (sic) with pregnant wife Mary at a homestead in Durango, Colorado. George raises horses with Harry and in 1884 moves his family to Cortez. Harry stays with them but works as a wrangler for Henry Goodman, foreman for the LC Ranch. Other families stake their claims in the nearby La Sal Mountain area – one is McCarty’s. Close by at Mancos are the Maddens – Harry and Bill, who figure in a train robbery with Sundance in 1892. Many key outlaw partnerships blossom from southwestern Colorado.

Will Carver (aka GW Franks) is born on September 12, 1868 in Wilson County, Texas. Youngest of two, his parents George and Martha Jane Carver are originally from Missouri and move to Texas in 1863. Will leaves the family home in 1880 in search of adventure. Riding out with his uncle Dick Carver, a man whose standing with the law is questionable, he begins his career on the Sixes Ranch (later the T Half Circle) near Sonora, Texas. Will builds a reputation there, meeting the Kilpatrick and Ketchum brothers who will play an important part in his later outlaw life.

In 1892, Will marries Viana Byler, but sadly, she dies of pregnancy complications within a year – the loss may well influence his subsequent behaviour. He joins Sam Ketchum in a saloon and gambling venture in San Angelo, Texas but a disagreement over debts with a John Powers results in Powers being found shot dead close to his home. Suspicion points to Will and Sam, who decamp hastily rather than face a trial.

Will becomes a full-time member of the Black Jack Ketchum Gang operating out of New Mexico. Along for the ride is Ben Kilpatrick (aka “the Tall Texan”) of Eden, Texas. The Ketchum Gang start their spree of train and bank robberies around 1896. The first is an ill-fated attempt to relieve the International Bank of Nogales, Arizona but they flee empty handed. In another, the gang is credited with netting a staggering $100,000 from the Santa Fe Railroad at Grants Station in November, 1897. A young, educated and highly intelligent cowboy named Elzy Lay joins Will, Tom Ketchum and Ben for that robbery. They escape to Alma, New Mexico and possibly there meet Bob Parker, who now calls himself Butch Cassidy.

The Tall Texan is born Benjamin Arnold Kilpatrick on January 5, 1874, in Coleman County, Texas, his owlhoot nickname coming from his formidable six-foot-one frame. His father George serves in the Confederate Army then moves post-war to Bosque County, Texas and marries Mary Davis in 1869. They live in Hillsboro before settling in Concho County and by 1885, George is ranching, assisted by Ben, aged ten. Ben meets Harvey Logan (alias Kid Curry) working as a cowboy, and the two youngsters strike up a friendship which lasts until the final days of the Wild Bunch.

Ben, Sam Ketchum, Will Carver and Dave Atkins all work for the T Half Circle Ranch near Knickerbocker, Texas between 1881and 1891. Later, Ben drifts to New Mexico and works in the Erie Cattle Company alongside Will Carver and the Ketchums. He then appears at the Victoria Land Company, later known as the Diamond A Ranch, before arriving at the WS Ranch in Alma under the alias of Slim Catlow. These ranches all play an important part in the Outlaw Trail.

Harvey Alexander Logan is the fifth man. Harvey, better known as the infamous “Kid Curry,” has no official birthday, as nobody agrees on a date or place. Estimates group around 1870, the most likely being Richland, Iowa in 1867. Harvey has three brothers and possibly a sister. Orphaned at an early age, he grows up without parents on the farm of his aunt Liz Lee, learning the cowboy trade before departing for work in the stockyards and on the trail drives of Dodge City, Kansas. Excitement draws Harvey west – by 1885, he has met Ben Kilpatrick at Big Springs, Texas.

Aliases are commonplace amongst the outlaws of the period, and prove invaluable for nearly all of them in an age when identification is always uncertain. Harvey’s principle alias, Kid Curry, is used throughout his adulthood absolutely interchangeably with his real name, and subsequent records invariably cite both names. Circa 1890, Harvey, together with his brothers Lonnie and Johnny, buys a run-down ranch on the headwaters of Rock Creek, south of the Little Rocky Mountains. They soon fall foul of the town’s founder, Pike Landusky. A feud ensues, and the conflict finally results in Pike’s death during the Christmas festivities of 1894.

Despite acting in self-defence, shortly after the shooting Harvey rapidly leaves Montana – possibly to stay at Hole-in-the-Wall, Wyoming. Here, Harvey meets with old friends, probably Butch Cassidy, and becomes a member of the blossoming “Train Robbers Syndicate.”

SIMON:

Butch led the outlaw band known variously as the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, the Train Robbers Syndicate and the Wild Bunch. He perfected a strategy that in North America remained undefeated for eleven years. The gang cased prospective hold-up sites carefully, noted the best getaway routes, cached food and ammunition and placed high-quality horses at strategic intervals across the West. Their robberies were successful because Butch researched so thoroughly, and his excellent planning netted big gains. The gang hauled impressive amounts of cash, and well-planned escapes across difficult country ensured that local law enforcement and part-time posses were easily outrun.

By 1899, Butch’s Wild Bunch was beginning to feel the heat. Big money was put up by the Union Pacific Railroad to catch the bandits who had been robbing trains with impunity. There was much more communication and cooperation between different States and law enforcement agencies, and Butch and Sundance’s adversaries were now real man-hunters – seasoned, cunning trackers, fearless and very well paid. Butch and Sundance were exceptionally good at what they did, but so was this group of ex-lawmen and bounty hunters publicised as the Super-Posse.

EH Harriman of the Union Pacific Railroad was an extremely wealthy entrepreneur who acquired the rolling stock of the railway in the early 1890s. By 1898, train robbery in Wyoming was an embarrassing problem. The Union Pacific was being relieved regularly of considerable bank and payroll funds, and something urgently needed to be done to stem the flow.

Hence the handpicked Super-Posse, heavily armed and superbly mounted, assembled into a highly organised mobile troop and conveyed to likely holdup points in modified baggage cars drawn by specially built fast locomotives. Ruthless (and some say unscrupulous) Joe Lefors is usually credited with leading this posse, though some sources suggest Big Tim Kelliher actually headed the new division under Harriman’s authority.

The renowned Pinkerton Detective Agency also allocated two of its best operatives to the manhunt. Charlie Siringo and WO Sayles were both courageous men and expert trackers. Siringo in particular was absolutely tireless. He spent four years pursuing the Wild Bunch and claimed to have ridden in excess of 25,000 miles in search of the bandit riders.

Other railroad companies retained or encouraged freelance bounty hunters to join in the hunt, men with fearsome reputations like Frank Canton, Fred M. Hans, William H. Reno, and George Scarborough.

The message was clear and simple: Butch, Sundance and the Wild Bunch must be hunted down, and expense, time and distance were no object.

Eventually and inevitably, the long-run criminal success of the Wild Bunch brought national notoriety. Ever larger rewards were posted for their capture, and, tempted by fame as much as finance, numerous public and private man-hunters joined the search. Between 1889 and 1901, Butch and his pals had made off with some $200,000 – the equivalent of $4 million today. But you don’t survive twenty years in the bandit trade unless you are very smart indeed. No way could Butch and Sundance not have been aware that it was only a matter of time before they were all hunted down, captured or killed.

OUTFITTING THE OUTFIT

“Everything’s harder than it used to be – you got to be damn sure what you’re doing or you’re dead.”

BUTCH CASSIDY

RICHARD:

From the air, Texas west of the Pecos looked a little bit like parts of the Ogaden region of Ethiopia – real badlands, a yellow and brown sun-baked landscape of sand and scrub, with enough rocks and hidden canyons to hide an army. We were crossing the Llano Estacado, the Staked Plain, when a voice came over the intercom warning us of turbulence. Minutes later, the sky disappeared. We were flying through a sandstorm. The plane was buffeted mercilessly and plummeted twice as it hit big air pockets. It was as bad as anything I’d experienced, and Simon and Barbara were both looking decidedly green. I hoped neither of them would lose their lunch. It was a relief all round when we touched down. Stepping out of the plane, the heat hit you like a furnace.

Rusty Armstrong, our hostess and outfitter, arrived in a huge black GMC pickup truck. We headed north to the horse ranch in La Mesa, a small Spanish settlement south of Las Cruces. At Vado, we bumped over the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad line and followed the back road for nearly four miles. Then we swung into the driveway, our preliminary journey over and the important one just about to begin.

Plans were to spend a week buying equipment. We would be riding and trial-packing the horses Joe Armstrong had already bought on our behalf. Joe, in his fifties, is a very successful equine and agricultural professor teaching locally at the Las Cruces, New Mexico Student Union. He is a bear of a man and a true southern gentleman. When his wife Rusty isn’t running the daily business of the ranch, she organizes endurance races throughout Western America. Together with their bright sons, they make up a very impressive family, and Simon did well to find them.

Buying horses is never easy. During the spring and summer sales, you pay more for the privilege since the ranches always increase their herd to be ready for the international holiday season. We would appraise our mounts next day. Over dinner in a very good local Mexican restaurant, we discussed short-term plans. The choice was whether to scout the country near the border ahead of departure or to start buying equipment and working the horses straight away.

We would take five horses: two to pack and three to ride. The remuda comprised a ten-year-old, sixteen-hand black gelding, a seven-eighths thoroughbred quarter-horse (and an ex-racehorse to boot). I named him Yossarian after the character in Catch 22. We shortened it to Yazz. The other black gelding was an ex-ranch horse aged seventeen. He stood fifteen and three-tenths hands and was the “horse with no name.” Dube (Doobie) was a twelve-year-old sorrel, sixth-eighths thoroughbred quarter-horse around fifteen and three-tenths hands. A mean looking twelve-year-old chestnut cowpony was the smallest, standing at fourteen and three-tenths hands. Joe named him Outlaw.

Finally, there was an Appaloosa mare. She stood at fifteen hands, and at six was the youngest of the bunch. We re-named her Miss-Ap. She was almost a pure grey, but was of course sprinkled with the small reddish-brown spots that distinguish the breed. We agreed Barbara would rotate the smaller three, leaving Dube as Simon’s saddle horse and Yazz as mine.

Our equipment comprised:

~ three Western riding saddles, including a heavy roping saddle (two centerfire and one rimfire)

~ two sawbuck packsaddles, with two pairs of heavy-duty brown-coloured carbon fibre panniers

~ tack, including lead ropes, halters and bridles, morales (nosebags), leather hobbles

~ neatsfoot oil, spare leather tie strings

~ two axes and one military folding shovel

three canteens, three military water bags and a canvas bucket

~ horseshoes, nails, hammer and file

~ fencing pliers and baling wire

~ three Silva compasses and a Magellan Global Positioning System (GPS)

~ a pair of binoculars

~ a complete medical kit, including needles, snakebite kit, painkillers, antibiotics, bandages

~ a comprehensive horse medical kit, including gall salve, sprays, antiseptic and bandages

~ stove, fuel, lighters, lantern and matches

~ two Dutch ovens, two pots, a frying pan, three plates, three mugs and cutlery

~ a three-man tent

~ bedrolls and military Gore-Tex bivvy bags

~ three “four season” sleeping bags

~ plastic groundsheets (large and small)

~ spare ropes

~ yellow slickers

~ two cameras, a video camera, numerous films, a charger and a fax modem

~ .30-30 Winchester rifle, and Smith & Wesson .38 Special handgun, with shells for each

~ notebook, pens and diary

In addition, we bought supplies of cooking oil, spices, candy, herbs, flour, coffee, pasta, biscuit mix, sugar, nuts, beef jerky, powdered milk plus 100 pounds of sweet feed (two bags).

SIMON:

How much riding preparation did we embark on before leaving England? Barbara kept a beautiful Russian stallion in Suffolk and rode most weekends. Her riding experience extended over more than forty years. Richard had recently joined her to get the feel of being with horses again. He had not been in the saddle for five years. Nor had I for over a year. Months earlier, Dylan Winter had informed me he rode in excess of thirty hours per week in preparation for the Oregon Trail expedition. I was shocked and panicked. But it was already far too late to start worrying.

I knew I was facing a stiff challenge. Never considering myself a real horseman, I would have to learn the hard way. If the average rider for pleasure hacked out for two hours a week, and assuming we would spend around eight hours a day in the saddle, I calculated that just two weeks would give me the equivalent of a year’s experience!

After breakfast, we drifted over to an enormous white barn. Adjacent was a sandy arena split by a tree-lined drive, holding pens and two lush pastures. Behind were more pens full of brood mares, colts and fillies. The studs were safely housed in the horse barn, part of an impressive breeding programme.

The ranch house nestled securely amongst the cooling cottonwoods. Green, irrigated pastures were home to horses contentedly grazing. Beyond, through hazy sunshine, lay the foothills of the San Andres Mountains and San Andres Peak towering at an impressive 8,241 feet. The customary New Mexico spring wind blew frequently. It was hot and dusty.

With generous assistance from Joe’s Mexican hands, we tacked up for the first time. Richard had no idea how to saddle with Western tack, but my time with AC had left me with a good working knowledge of the equipment used and the riding style. Like most things in life, it’s simple when you know how and it’s no black art, but even so, one of the hands managed to over-tighten the cinch on Dube, which cold-backed him.

This is an immediate reaction to cinching too fast and too tight without letting the horse acclimatize to saddle pressure. To our alarm Dube suddenly collapsed to his knees and flipped onto his side. The situation was compounded, as the lead rope had been secured to the hitch rail a little too short, and the horse was head-locked. Dube panicked, but luckily Joe Armstrong was on hand to free him. Dube suffered no ill effects, and we got busy.

On ranches, it is still considered good sport to put the new pilgrim-up on a spirited horse, like Gregory Peck in William Wyler’s The Big Country. So naturally, neither of the black geldings had been exercised in advance. I discreetly decided to let the more experienced Barbara and Richard take the edge off their friskiness. All went well until Joe politely insisted I fork the saddle.