Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Eye Classics

- Sprache: Englisch

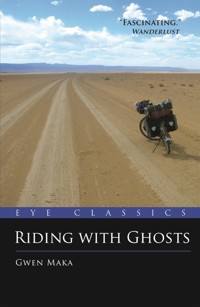

Gwen Maka, a forty-something Englishwoman, was told by everyone that her dream was impossible. Gwen's solo ride takes us across the deserts and vanished Indian trails of the American West, over the snow-peaked Rocky Mountains, down Mexico's Baja coast and finally into the sub-tropics of Central America. Her journey is intertwined with the legends of past events; as she rides through unwordly landscapes, the ghosts of the American Indians and pioneers who shaped the Americas travel with her. Riding with Ghosts is Gwen's frank but never too serious account of her epic 7,500 mile cycling tour. She handles exhaustion, climatic extremes, lechers and a permanently saddle-sore bum in a gutsy, hilarious way. Her journey is a testimony to the power of determination.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 486

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This Eye Classics edition first published in Great Britain in 2010, by:

Eye Books

29 Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

First published in Great Britain in 2000, as Riding with Ghosts and Riding with Ghosts: South of the Border

Copyright © Gwen Maka

Cover image copyright © Bryan Keith

Cover design by Emily Atkins/Jim Shannon

Text layout by Helen Steer

The moral right of the Author to be identified as the author of the work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-903070-77-2

Note on terminology:

While writing this book I have been conscious of the current pressure to be ‘politically correct’ in the written and spoken word. In the case of North American tribal peoples I believe that ‘Native American’ is currently politically correct among white Americans. However, not only did I find this at times clumsy and impersonal, I also, in my travels, never met any individuals who used this term about themselves. Rather, they used tribal names or, more generally, ‘Indian’ or ‘American Indian’. I also found this the case in books.

When I read of a prominent Oglala Sioux (Lakota) proclaiming that ‘Native American’ reminded him of the repressions practised against the Indian, and of his belief (and of others too) that ‘Indian’ does not — as commonly stated — come from Columbus’s belief that he had found India (which at that time was called Hindustan) but from the gentleness of those aboriginals encountered by him, so that they were ‘una gente in Dios’ — a people of God, then I was satisfied that these terms were not offensive in any way.

Therefore, in all cases historic I have used the tribal names or ‘Indian’. When referring to native people of the current era I have again used the tribal name where this is known and relevant, and interchanged Native American, Indian, American Indian, tribal peoples and Native people, when talking more generally.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For Ethan and Savannah.

Thanks to Dan Hiscocks of Eye Books for taking the risk of a new edition and accepting my wish to do a vastly revised script — and for his inspiring ideas and advice. To Helen Steer at Can of Worms Enterprises for her hard work and patience at my many script revisions.

Thanks to John and Jane Snow, Linda Raczek, Linda of Coeur d’Alene, Selina, Martha, Armin and Maria, and many others, for opening their homes to me. To all the wonderful people I met along the way who constantly humbled me with their many kindnesses and who never showed any resentment of the fact that my ‘pains’ were personally inflicted and voluntary. Their ability to keep laughing in the face of immense daily difficulties filled me with admiration, brought colour to my days, and made me realise that you can have nothing yet still be generous with kindness.

My special thanks to Julian, for his endless inspiration and for still being out there somewhere — still cycling. He made it seem quite normal to get on a bike and cycle for a year.

But above all, I thank all those solo women travelling alone in every corner of the world — by foot, bicycle, train, bus, canoe, car, whatever — with confidence and courage and flagrantly defying those doom mongers who are always warning us what a dangerous place the world is. In my travels these solo women always provided intelligent companionship, however short, whenever I met them. Christy Rodgers (who, when not travelling, publishes the radical journal ‘What If…’ from her home in San Fransisco) deserves special mention for her unassuming passion of quietly trying to make the world a more ‘thinking’ place. Such women can truly motivate the rest of us and show us that women alone, of any age, do not have to stay at home, whilst the older among us can dream, not of what we can’t do, but of what we can do — or more specifically, of what we can try to do!

CONTENTS

RIDING WITH GHOSTS

Introduction

Leaving Seattle

Hockney Landscapes

Big Hole Battles

Craters of the Moon

Shooting Stars

Road to the Rockies

Red Mountain Pass

Winter Wonderland

Mesa Verde

Hitchhiking Detour

Back to the Saddle

Canyon de Chelley

Navajo Days

Hopi Horizons

Border Country

SOUTH OF THE BORDER

South of the Border

Floating on the Old Wharf

Beach Bums

Bag Lady

Copper Canyon

Doom Mongers

In the Steps of Pancho Villa

The House of Eleven Patios

Bad Decisions in the Valle

Testosterone Taxco

Bikini Anna

Confused in Guatemala

Pacific Waves

Rats at Sarah’s House

Deep Waters

Sandinista Country

Down the River

Dripping Trees

“History… creates the insidious longing to go backwards. It begets the bastard but pampered child, Nostalgia. How we yearn… to return to that time before history claimed us, before things went wrong. How we long even for the gold of a July evening on which, thought things have already gone wrong, things have not gone as wrong as they were going to. How we pine for Paradise. For mother’s milk. To draw back the curtain of events that have fallen between us and the Golden Age.”

Graham SwiftWaterland

RIDING WITH GHOSTS

Seattle to Mexico

MAP: SEATTLE TO BAJA

INTRODUCTION

I really didn’t know it would be like this! As I sweated and cursed my way up the never ending hill which culminated in the Loup Loup Pass I wondered how on earth it was that in a lifetime of cycling I had managed to reach the age of forty-five without learning that cycling uphill could feasibly kill you.

And in all these years why didn’t I know that wind wasn’t only something that gently swayed the tree tops, but was really a malicious and vindictive spirit whose sole reason for being was to hurl me under the wheels of any passing articulated lorry or sling me into the deepest muddiest roadside ditch, and whose buffeting blasts could quickly reduce my world to a swirling maelstrom of humourless hell?

After all, since being a child I had often seen cyclists loaded down with luggage, pootling leisurely up steep hills without breaking a sweat, even having the energy to wave at me as we passed by in the car, so I already knew how easy this bike malarky was! How envious I’d been of them when they erected their cosy little tents next to my parent’s caravan, and lit their cute little cookers as they sat on the soft green grass and watched the burning sun go down. I would watch them jealously, embarrassed by my indoor luxury. I mean, cycling tourists always had fun, didn’t they?

So it was that for years I’d been longing to set off on my own Grand Tour; it was something that I knew was going to happen some day. I just had no idea how or when or where. And as my parents refused to go abroad (‘there’s plenty to see in this country’) and as I was always financially challenged, I was thirty-four before I finally got beyond Britain’s shores on a bus to Brussels for a weekend demo.

For many years the travelling idea got stuck in the cobwebs of daily survival; I was a single mother trying to juggle what had to be done without the means to do it. I remember thinking of life as a hurdle race — I would just get over one hurdle when I had to prepare for the next one, which I knew was just around the corner!

Then, one day, as I returned from the supermarket on my bike, laden down with six precariously wobbling carrier bags of food for my three teenage sons, an idea began sneaking into my mind. It was like a virus which had lain dormant for years, and suddenly it burst forth into a fully fledged outbreak….

I would go cycling!

Why did it take so long for such an obvious idea to form? Why hadn’t I thought of this before? So convinced was I by this revelation that over the next few months I bought four Carradice panniers, a beautiful silver Dawes bicycle, and booked myself onto a Teaching English as a Foreign Language course — I thought it might come in handy. The panniers went into the waiting room of my airing cupboard, the TEFL was done in my summer holidays, and the bike was stolen twelve months later.

After my children had more or less left home and my little dog Flossie was no more, I decided it was time to use my TEFL skills to see a bit of the world and hopefully raise some cash for my ‘one day’ cycling trip — wherever that may be. Sticking a pin in a map to make the decision of where to go it landed on Turkey, so I left work, jumped on a ferry and after a month arrived in Istanbul. Once there I thumbed the local yellow pages, knocked on doors and soon found work teaching English to spoilt little rich kids and polite attentive big kids and settled into a happily chaotic life in that addictive metropolis.

In the end it was Justin who was the catalyst. My days were floating dreamily by in the smoky haze of non-descript cafes and drifting conversations with a variety of carpet seller friends — lazy conversations dominated by petty gossip; the perpetual elusive carpet sale; how to get home at midnight on fifty pence; which tourists wanted the weed; and always, always, the lack of money. Heady stuff!

The reason it is his fault is because one mellow, yellow day he turned up at my current hostel on his bike. Justin, I should mention, is one of the untamed of the twentieth century — a truly natural traveller; a meanderer on the planet who is vaguely circling the world, but with diversions that are long and fascinating. He arrived from Russia complete with donations of three large glass jars of bottled preserves, several pounds of potatoes and piles of butter — all the heaviest things you can imagine — determined to defy those dedicated lightweight cyclists who decimate everything from toothbrushes to gear levers in order to reduce their weight as much as possible without personal physical amputation. He argued that as he wasn’t carrying it, it was no problem. I was to discover that this was not a logical statement.

With financial considerations taking top priority we decided to share a room for the winter. The result was a fourth floor room with huge corner windows which fully encompassed the magnificent vista of the Blue Mosque, like a glorious three-dimensional Walt Disney screen. This scene flooded our senses daily, and for the remaining months we constantly had to remind ourselves that we were not living in a fairy grotto, or in the white witch’s wonderland.

One hot afternoon Justin was out and I picked up his mini world atlas. Of course, it was obvious, I would cycle from Seattle to Panama. A quick decision.

And yet, not really so quick. Ten years earlier I had visited the United States where I had spent six weeks in my tent, studying development on the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Sioux reservations of South Dakota — the homes of the Brule and Oglala Sioux. This trip was undertaken with a staggering combination of ignorance,stupidity and such a lack of funds that the Greyhound ticket seller in New York got fed up with me asking,

“How much is it to go to x, or y or z?”

“Where do you actually want to go?” he eventually asked.

When I told him, he just gave me a ticket and said,

“Just give me what you’ve got.”

Following a combination of camping, hitch-hiking, starving and a whacking dose of luck, I left America very much thinner but also very much wiser. I had gained a greater understanding of the harsh realities of life on the reservations, of land distribution, social problems, education, intra-tribe conflicts, etc.

I was also wiser about my own survival. Things such as how to return the seventeen hundred miles to New York in three days with only four dollars; how to live with my own company; learning that I never again wanted to travel with a dependence on others — I needed my own transport; learning how to take unavoidable risks and accept the possible consequences; to be adaptable, to trust my hunches.

But the most overwhelming emotion I left with was a powerful confirmation that my previous imaginings of ‘how America was’ were correct. It felt how I thought it would feel but even more so, because no written words can express the magic which hovers over those wonderful wide open rolling plains, nor can they convey the vibes of the past which shimmer in the golden air and permeate the land.

And most importantly, I discovered that when travelling alone, and in dire straits, an internalised need really does become an external reality, just as the philosopher Karl Jung said — I believe the word he used was synchronicity. Thus when things get tough, the niches for survival open up, like another dimension. You learn to ‘live between the lines’, to see them, so not only do things turn up just when you need them, but you begin to feel almost an instinct about any situation.

I remember one night camping in my tiny tent on the open prairie outside Rosebud village.

I was hungry, lonely and a little depressed. It was evening, and the sky filled the world — so huge and so blue. I went to the brow of a nearby hill and watched as from the west an enormous fluffy cloud came floating through the blue — a thunderhead. It was a great billowing mass, and within it a magical thing happened — as the lightning flashed and thunder crashed that cloud flickered on and off like a bright light in a white tent.

It was a revelation for me, who had never before seen a storm contained within a single cloud, surrounded by a clear sky. In Europe a lightning storm means low grey clouds that smother your head, the lightning comes from an unidentified source, and the world is enclosed in a fierce, murky onslaught of darkness and close horizons. But that evening on the Rosebud nothing happened in the clear blueness of the sky beyond that South Dakotan cloud, and it drifted sedately on its way across the heavens — all the energy and the drama remaining within itself.

I found some wild choke cherry, lit a fire and cooked them. I made a cup of tea and continued my reading of Black Elk Speaks and read of how, more than a hundred years before, the medicine man Black Elk had also camped on the Rosebud at a time when he was unhappy about the fate of his people, the Sioux. I read of how he went to the brow of a nearby hill, and as he sat there a thunderhead passed, and thunder crashed and lightning flashed within it. As he watched the great cloud pass he felt at peace once more and knew what he must do.

Some would call this coincidence. I call it synchronicity.

Yes, in those lands everything felt alive — the land, its history, its rocks, the people who have passed through. A vibrant tactile thing emanates from the earth and wraps itself around you, draws you safely into its warmth. And so, planted in my mind was a desire to return.

The idea of just packing your bags and leaving is an attractive one, but in practice few can do it easily, for even without work or family commitments the accumulation of age is almost invariably accompanied by a parallel accumulation of cumbersome life debris, although desperation at the passing years can sometimes lead to a ruthless eviction of some of this.

I recall a wonderful down to earth Australian friend, Jan, who regularly threatened her two wild teenagers that if they didn’t toe the line and make her life less stressful, then one day they’d come home and find she’d fled to Timbuktu. And indeed, one day they came home and found she’d fled, not to Timbuktu, but to Istanbul, where I met her. She was making good money teaching English which she proceeded to pass on to a series of dubious boyfriends who fattened up nicely under her benevolence, until four years later she returned home to her, hopefully, now contrite children.

I only had two months to prepare for America. Of that, one month was taken up with completing some outstanding work, and two weeks were to be used for a final visit to my three now grown-up sons who lived in Mallorca. This left two weeks to find someone to live in my house, deal with bureaucracy and, most importantly, equip myself for my trip, including the main item of buying a suitable bike to replace my previous stolen one. But I still had my panniers which had been waiting patiently for me these past ten years. With great ceremony, I lifted them out and attached them to my spanking new bike, another Dawes, green and elegant and already loved.

Then, at eleven o’clock one night, a day and a half before abandoning my house, there was a knock on the door. There stood Justin. He had cycled from the ferry at Felixstowe to Norwich without stopping (seventy miles) and now informed me that my twenty-one gear bike was no good for the Rocky Mountains. The gears were not low enough and needed replacing.

“Blimey,” I asked him, “how big are those hills?

“Big!” he replied.

By this time I was in a state of total exhaustion and confusion, as every day produced yet another long list of tasks to complete. I hadn’t even had a chance to think about the journey at all; I’d made no plans whatever; I was just going to jump in at the deep end and go. If I’m honest though, I knew that it wasn’t only that I hadn’t had time, it was also the only way I could do it; it was the way I worked. If I’d thought about such a massive undertaking then I would have been be forced to face all the things that could go wrong; all the reasons not to do it! It was just too scary!

I know many people plan for months, even for a trip in Great Britain, and I imagine everyone plans for something more adventurous, especially if some degree of self-sufficiency is involved. But I believe that if I had started researching (and internet wasn’t widely available at that time) then I’d never have set off, I would have been too daunted by the scale of the whole thing and would have chickened out. By simply making the decision to go, and booking a ticket, it was done, I had to go. The result was that my US map was just a road map with very little detail, (so I hardly even knew where the mountains were); I had very little money; knew nothing of the climates, geography or potential dangers. In fact, all I really knew for certain was that I would be starting in Seattle with the aim of getting to Panama — or wherever I ran out of money. I’d just get over to America first and take it from there, a day at a time, and see what happened. And that’s what I did.

What really got me wound up and frantic was the work involved in actually getting away, not worries about the trip itself.

“I can’t stand it! I just can’t do anymore,” I whined.

“It’s okay. You’re already there. You’ve already done it,” said Justin.

And yes, I had. I had let my house, organised bills, bought a one year return ticket. I was ready to go. But on a night of one too many beers I had also agreed that an ex-work colleague could come with me for the first month and I was having serious reservations about this. But as she had presented me with a fait accompli when I returned from Turkey, and not wanting to disappoint her, I agreed, telling myself that it might ease me gently into the start of my otherwise solitary journey.

Not having been on a long bike journey before it was a bit of guess work trying to decide what was essential equipment and what wasn’t. All the planning in the world won’t get it exactly right, especially when it comes to things like bike spares. It is only in situ that you learn to distinguish between essentials, usefuls and waste of spacers. A long trip (either by time or distance) is made considerably more difficult as climatic and/or seasonal zones will be crossed. So for example, whilst lots of clothes may be a must for the first months, you don’t want the extra clutter when the temperature starts to rise.

In theory items can be shipped home but travelling on the economic margins does not permit the flexibility of buying new gear and shipping out old. As I was calculating on a paltry five or six dollars a day (it was go with this or not at all) I had nothing over for emergencies or luxuries.

In spite of lots of experience in camping, I made three major errors in my choice of equipment, all of which were totally inexcusable.

The first, and biggest, was in not replacing my three season down sleeping bag with a five season synthetic one. I really didn’t imagine it could be so cold as it was during the long dark winter nights in the Arizona desert (research?!). I was going into the unknown and turning a bike ride into a survival expedition.

My second mistake I blame on the iconic long distance walker Chris Townsend who gave an impeccable review for a light weight, single skin Gore-Tex tent which he claimed to have used in the hurricane conditions of his two thousand mile walk through the Canadian Rockies. This tent deposited lakes of condensation on me in any conditions damper than the Sahara Desert (he subsequently wrote another review where he completely reversed this initial verdict). It also took ages to dry. I would never buy another single-skin tent however tempting they may look!

Another mistake was buying a very expensive multi-fuel cooker which caused me many tantrums over the months. At times I had to wait a couple of days until I had calmed down sufficiently to deal with its eccentricities in a reasonable manner.

The moral of all this is not to buy untested equipment when embarking on a long journey, and to do some research into weather conditions.

Finally, because my decision to undertake the trip had been a quick one, I had not had the opportunity to train. Not that I would have anyway. I reasoned that there was little point in cycling hundreds of miles a week when I could use the trip itself to train. As a consequence my first days reached a pathetic twenty-five miles a day. After a month I was up to fifty and gradually increased until I stabilised at around eighty with a maximum of ninety-five on a day of mountains in Mexico. (I was flabbergasted by those cyclists who claimed mileages of up to two hundred miles when loaded up.) But I wasn’t in a hurry; wild camping is a great pleasure for me and my great satisfaction is to stop early in the day and spend the remaining daylight hours enjoying my surroundings.

LEAVING SEATTLE

On a sunny day the Puget Sound must glimmer and glisten around the islands and headlands like a jewel, and though the day was grey and damp it was, for Seattle, a good day; the sun had only been seen twice this year, I was told. Given the abysmal lack of summer throughout the country I could well believe it. I had imagined mid-August to be a late start to my ride which would mean rushing in order to reach the Rocky Mountains before the snows of winter fell. But as it happened, 1993 had been a freak year of unquenchable deluges resulting in widespread flooding of the Missouri floodplain. To travel earlier would have been misery.

Seattle was my introduction to the ‘skid-row Indian’. These much maligned urban down-and-outs are tragic figures who cannot cope soberly with what history has thrown at them and their heritage. Chief Seattle, after whom the city is named, realised that the unstoppable tide of whites would eventually destroy his people. In a long moving speech (now thought to have been sexed up by the media) he said:

“When the thicket is heavy with the smell of man… then it is the end of living and the beginning of survival.”

Sadly for many of his descendants, survival is found at the bottom of a bottle. Whilst present-day Native Americans may not have direct experience of ‘what once was’, they have, I believe, a culturally inherited memory of what they have so recently lost. This memory remains strong, and it is one which can either eat away at the spirit or be directed into positive energy and determination.

A Maori friend spoke of this to me once. I had been to see a violent but excellent film about inner-city Maori culture, called Once Were Warriors. I asked him about its accuracy and how such alienation could be avoided.

“That was a road I could have gone down,” he told me. “In the short term it’s the easiest way. You can either direct your energy negatively, screwing yourself up with all the wrongs that have been done to you, or you can say, ‘They aren’t going to beat me; I’m not going to let them ruin the rest of my life,’ and channel your energy productively.”

When I visited the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Lakota (Sioux) reservations of South Dakota twelve years ago, the initial scene was one of cultural desolation. Wife and child battering, alcoholism, dependency, tribal government corruption and conflict, racism, violence and unemployment; it had the lot. An old man lamented that nobody had visions any more. He didn’t know why.

The following day, three unemployed men (two Sioux and one Navajo) sat in a shabby living room with the television blaring out; simultaneously a cassette was playing. Nobody was listening to either. As I looked on this depressing scene they suddenly began playing their drums, shaking a gourd and singing traditional songs, totally oblivious to the parallel chaos. I did a retake on my first impressions.

Later, a pony-tailed man showed me the scars on his chest and back and explained that they were the result of his participation in the Sun Dance. This is an ancient ritual practised with variations by tribes throughout the country. It usually involves painful ordeals of body piercing in which hooks (originally eagle talons) are inserted under the muscle into the chest or back and attached by a line to a cottonwood pole or heavy buffalo skull. Gradually the hooks are torn out by the force of body weight against the pole. The ritual is variously described as being for self-sacrifice and prayer, the acquirement of power, the giving of thanks to Wakan Takan the creator. It was banned in 1881 and for many years went underground. Happily it is now enjoying a revival — with some changes in method — and this particular year a ten year old boy had undergone the ordeal.

In his autobiography Lame Deer, medicine man on the Pine Ridge reservation, says that some of the older generation criticise the present-day participants of the Sun Dance, saying; ‘they don’t go underneath the muscle,’ ‘it’s only the flesh,’ or ‘the young men have gone soft,’ and so on. Lame Deer gave his response to this criticism:

“These dancers work for a living… in a few days they must be fit to pitch hay, drive a tribal ambulance or pick beets. One did not need money in those old days. While a dancer’s wounds healed, the hunters brought him all the meat he and his family could eat.

No, in many ways the dancers of today are braver than those of days gone by. They must fight not only the weariness, the thirst and the pain, but also the enemy within their own heart - the disbelief, the doubts, the temptation to leave for the city, to forget one’s people, to live just to make money and be comfortable.”

When earlier generations took part in this annual ritual there had been little to induce doubts in the ancient belief system; the American Indians believed totally in their world of mystery and spirits and visions were their everyday life. In these days of high-tech and internet, how much harder it must be to hang on to traditional ways.

When more than two hundred men, women and children were massacred at Wounded Knee, South Dakota in 1890 Black Elk wrote:

“And so it was all over. We did not know then how much was ended. When I look back now from this high hill of my old age, I can still see the butchered women and children lying heaped and scattered all along the crooked gulch, as plain as when I saw them with eyes still young. And I can see that something else died there in the bloody mud and was buried in the blizzard. A people’s dream died there. It was a beautiful dream….”

Although the Cascades do not reach the elevation of the Rockies and the passes are relatively low at around four or five thousand feet, nevertheless they are rising up from sea level. In western Colorado even the valleys may be at seven thousand feet so the rise to an eleven thousand feet pass may still only be a four thousand feet climb. In other words, the Cascades were tough for a beginner.

The moss-covered forest allowed few grand vistas, just tantalising glimpses of eerie shrouded spires of rock and — where the land opened out along rivers — the incredible translucent blues of mountain waters.

In addition, this was black bear territory and the business of hoisting our gear up trees at night was not only a nuisance, it was impossible. After many failed attempts to throw a line up the tangled trunks of massive droopy conifers we lowered our standards to a point where a coyote pup would have had no trouble reaching our goodies.

At the top of Washington Pass I was horrified to see snow drifting to the ground. This was August, for heaven’s sake, how can it be snowing? I had visions of dying a cold lonely death in the Rockies in October. But then the sun came out, and it was a glorious fourteen miles downhill, the temperature and morale rising with every bend in the road.

Suddenly I burst out from the darkness of the forests and into golden-flecked, sun-bathed, rolling grasslands. Cattle and horses grazed in meadows of wild sunflowers; it was dry and sunny and I could see for miles. I felt a great sense of relief as the cold wet nights of the Cascades were left behind and my spirits soared as I bowled into the museum town of Winthrop.

HOCKNEY LANDSCAPES

Looking back over my diary entries, the most common introduction to each day is variations on the theme of, ‘My god, what a day!’ The first such entry occurs on August 25th.

Enjoying the ease of riding in the pleasant valley of gentle hills which surrounded the close-knit communities of Twisp and Winthrop I was suddenly confronted by a signpost indicating that this sharp turn-off was mine. Apparently this was the Loup Loup Hill, which culminated in the Loup Loup Pass, the one that made me wonder what the hell I was doing here. Anywhere you see the word ‘Pass’ be prepared for a slog — I had learned that much — but the easy valley had lulled my body and mind into dreamy lassitude. I had my amazing little computer telling me everything I wanted to know about speeds and distances and things. On bad days it told me things that I didn’t want to know, on good days it motivated me to better things. It was a bit like the proverbial half cup of tea — is it half full or half empty? A bike computer is the same. On a good day it tells you how far you have gone, on a bad day it tells you how far you have still to go. The real beauty of it though, is that it allows you to psyche yourself up and pace yourself for the distance you intend to go that day. There is little worse than thinking you have ridden at least forty miles, and then to find a sign that informs you that you have done only twenty. It is enough to make a plodder like me give up at that point. A huge gumption deflator.

For some reason I did not even know the Loup Loup existed, and in my still unfit state it nearly killed me climbing that mind-numbing hill — simply because I did not know where the bloody top was. Now I know that a miserable little eight miles can go on forever.

I suppose every long-distance walker, jogger, sailor and cyclist develops her or his own strategy for coping with physical and mental stress. In these early days, hills and mountains were stress. My strategies for coping varied from mentally ticking off the distance on the computer in ever more tiny amounts — until I was counting tenths of miles — to counting pedal revolutions, so that every down-pedal on the right foot counted as one. After each thousand of these I thought I must be making headway. I also counted telephone posts and made up stupid songs.

One of the most wonderful moments in the life of an unfit cyclist in the USA — to which nothing can compare — is that exquisite moment when a yellow sign appears at the side of the road showing a little black lorry going downhill instead of uphill. This will be a few yards from another sign which says Such-and-Such-a-Pass Summit. After repeating obsessively to yourself: ‘I can’t do it. I must be mad. I can’t do it,’ you reach the top, breathe deeply, and gasp; ‘I’ve done it!!’

And the Loup Loup Pass was only a hill, for heaven’s sake.

In the Colville Reservation border town of Okanogan, my riverside searches brought me into contact with Sue, in whose garden I camped that night. She was later to play a brief but volcanic role in my life, but at this time I thought she was just a friendly local, and not the wacky person she turned out to be. I should have been suspicious when she declared that the large bird which had landed on a tree across the river was a sign that I’d “been sent”. When I returned three months later I discovered that this was its nightly roosting tree.

She also professed to have regular conversations with her dead grandfather who, she said, had been a lawyer and a medicine man. I could have accepted this more readily if she hadn’t been one hundred percent white.

It seemed to be a common phenomenon for whites to claim some Native American blood and to have tribal paraphernalia around their homes — tastefully (or not) integrated into the interior design of the home. If all those who boasted Indian heritage did indeed have it, there must have been some pretty fecund natives around in the last three hundred years.

This desire to have a Native connection suggests a certain spiritual disillusionment with white culture. To know that you have an Indian big toe must make you feel a bit more exotic than old droopy-drawers over the road. I know that I’d dredge the sewers for that roving cell if I knew it would enable me to imagine a strand of my ancestral line galloping across the plains having a whole load of fun.

The next day we reached Nespelem, the tiny capital of the Colville reservation. I had particularly wanted to come here because it was the place where Joseph, war chief of the Nez Perce tribe, spent his last years and where he was buried in 1904. Joseph is commonly held up to be the epitome of the noble savage — with the added prestige of being regarded as a military genius. His skills were exhibited during the fall of 1877, when he turned what was for his tribe a desperate flight and fight for survival — women, children, the old, tipis, horses and all — into a masterly rearguard action and withdrawal. His tactics are still examined ad infinitum at the Big Hole museum in Montana which I would later visit.

On their trans-American route-finding expedition of the early nineteenth century Lewis and Clark had been impressed by the friendly, intelligent and good-looking Nez Perce, who bred the spotted Appaloosa horse, farmed their ancestral lands in Wallowa Valley, Oregon, and hunted during the summer months in Washington, Idaho and Montana.

Up to the time of their flight the Nez Perce had lived peacefully with the whites for seventy years, and were still trying to do so with the settlers who were invading their valley in ever increasing numbers. To the everlasting shame of the government but consistent with their many callous decisions regarding the ‘Indian problem’, it was decided that the Nez Perce should be moved elsewhere and that whites should have access to all their lands.

Even then the tribe did not resort to war — merely asking that they be allowed to stay long enough to gather their scattered livestock before moving to their new reservation. This was refused, the outcome being that a group of young warriors were unable to control their justifiable anger and frustration. This led in turn to a skirmish and some deaths. Joseph said afterwards:

“I did not want bloodshed. I did not want my people killed. I did not want anybody killed.. I said in my heart that, rather than have war I would give up my country. I would give up my father’s grave. I would give up everything rather than have the blood of white men upon the hands of my people.”

But it was too late. The tribal leaders knew that the killings would bring down on them all the wrath of the army, so they quickly gathered what they could and set out on what became their epic four month, seventeen hundred mile journey. Their aim was to reach the sanctuary of Canada, where Sioux chief Sitting Bull was already taking refuge following his defeat of Custer the previous year, and where he had founded a community of displaced Sioux.

During the course of that tragic journey the Nez Perce were hounded mercilessly by the army, the cold being so severe that horses were killed so that young children and babies could be put into the warm carcasses. The tribe was finally apprehended at Bear Paw, less than forty miles short of the Canadian border, mistakenly believing that it had outdistanced the pursuing soldiers and reached the safety of Canada.

Small though this story may be in the vast annals of an often scandalous and shameful western expansion, it is nevertheless one that pulls strongly at the heart strings with its pathos. Joseph said afterwards:

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed… it is cold and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills and have no blankets, no food. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more, forever.”

Uniquely amongst the Indians of the West, Chief Joseph and his Nez Perce won the respect of the entire American nation at the time, unlike Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, whose present glamorous reputations owe much to hindsight and a change of attitude. The Nez Perce were admired as much for their humanity and chivalry as for the fact that for a while (despite three quarters of them being non-combatants) they consistently outmarched, outwitted and outfought the United States army.

Of course Chief Joseph eventually made peace, unlike wicked old Geronimo who fought like a tiger almost to the end in the southern deserts of Arizona and New Mexico, still technically a prisoner of war when he died in 1909. He has therefore always remained wicked old Geronimo — leader of the murderous and sadistic Apaches.

Looking today at the faded old photographs from that era, one is struck by the contrasting auras projected by the different tribes. The Nez Perce look out with intelligent, sympathetic eyes which comprehend those human conditions and emotions which we recognise — sadness, warmth, mischievousness. They are ‘of us’.

In contrast, the intense wary faces of the Apaches are alien to our air-conditioned lives; in them we see minds and bodies finely tuned to the harshness of desert living, and revealing nothing of the softness of comfortable living and easy choices. They are ancient and untamed; they speak to us of the primeval, of watchful predators, giving us a glimpse back to a wild pre-Columbian past.

But above all, the faces which stare at you from those old photographs are the faces of shell-shock victims, stunned by the tragedy and awfulness of their new alien lives, faces mourning the loss of a wild, roaming freedom and the lingering death of what must surely have been the most beautiful life lived by anyone, ever, anywhere, in the world.

In Nespelem I was told by a local woman that whites were not permitted to visit Joseph’s grave as it was also the general tribal graveyard. Later I was told that his head was not in the grave but in the Smithsonian Institute, together with the skulls of other ‘interesting’ Native Americans.

The feeling that history is alive and vibrant in the outback of America, and that if you are silent the ghosts of the past will speak to you and may reveal themselves, is at times overwhelming. When you meet Oglala Sioux children who ask you in all seriousness (as if it happened last week) if you think they were right to wipe out Custer and the Seventh Cavalry at the Little Big Horn, then you have to do a double take on the date. When someone points out the route along which the parents of Crazy Horse took his body to be buried in an unknown grave, and shows you the site of the 1890 Christmas massacre at Wounded Knee, you realise that those days are still powerful in the minds of the tribe. The present recedes from prominence and becomes simply the time we are going through at the moment — neither more nor less relevant than the past.

It is as though you stand before a translucent veneer which almost allows you to see the secret treasures on the other side; you glimpse vague shadows and shifting forms — to anyone who can stop and listen, the deafening noise of silence can be heard.

Not only does this massive land carry its Native Indian heritage within it, it also enters the psyche of the white American people. It pervades American art, music and literature; it looms huge in good and bad westerns; road movies can’t exist without it; small-town scenarios rely on it for their background atmosphere; poetry exudes it. Even when you can’t see it on screen or canvas or in words on the page, you can feel its presence in the unseen and unsaid.

The following day my mood was subdued. I had had a great time at a local dance the night before and wanted to remain at Nespelem a little longer but at this stage of my journey I was still imprisoned by the need to keep to a schedule, even though I didn’t know what that was, other than to get to Colorado before the snow.

Just as we were leaving the reservation, a man presented me with a feather from the protected bald eagle to protect me on my journey. I attached it to my handle bars and there it remained for the following twelve months.

Passing Davenport and the Grand Coulee Dam a new landscape approached. This was a landscape to be appreciated by the artist, not the ecologist. Devoid of trees, enormous undulating fields of rich, dark, freshly turned soil interspersed with acres of swaying and swishing yellow wheat. And yet the clean-cut lines which divided the large blocks of contrasting colours made it a land of striking beauty. The empty road meandered with the hills and an occasional tractor interrupted the emptiness, leaving a trail of dust. Overhead, the massive cloud-free sky was of the purest and most delicate blue. This, plus a golden orb and the occasional white tailings of unseen planes cutting across the heavens, brought vividly to mind the simplicity and clarity of David Hockney’s shimmering sunlit paintings.

In landscapes of such silent grandeur, events and characters often assume a greater significance than they would in a more cluttered world. Maybe it was the focus of my mind on more ethereal things which transformed the ravens, standing in pairs like conscious beings, into the spiritual guides assigned to them by traditional tribal lore. Certainly in those still days it was possible to believe anything.

Such mystical sentiments are smashed as soon as the local whites are encountered. They are of tough, uncompromising pioneer stock and, since their ancestors were obviously cut from the same unyielding cloth, it is no wonder that peaceful co-existence between whites and natives proved to be impossible. Nevertheless I found their down-to-earth, no nonsense matter-of-factness both refreshing and amusing. As I sat in a café in the heart of these wheat lands, an immaculate and extremely good looking woman in her seventies greeted a neighbour:

“How y’all doing?”

“Oh, not so good. Only firing on three cylinders today.”

“Well, shoot! You’d better get the fourth one operatin’!”

Stopping at a roadside coffee and cake stall down the road I found a similar attitude to life. The stallholder had buried her husband of fourteen months only the week before:

“No point sittin’ around,” she told me cheerfully.

Minutes later an RV, a car and a gang of Harley Davidson boys pulled in. A very thin and elderly blue-rinsed woman stepped from the RV, a middle-aged Seattle couple got out from the car, and the bike boys jumped cheerfully from their steeds. I was overwhelmed by the friendliness of this surreal combination coincidentally brought together in this lay-by. Blue-rinse reminded me of a virulently racist Afrikaner I had seen on television, until she smiled and told us about her dear late husband who, she said, had been part Indian. She was an avid reader of all things Native American.

She beamed at the bike boys. They beamed back. It was wonderful.

These Harley lads took me back to some heavy bike boys I had met on the plains of South Dakota back in 1982. As I was erecting my tent on a small-town site I was approached by six bearded and burly mountain men who were returning from a bike rally. They shyly asked if they could put their tent next to mine. I said sure but what was their problem?

“We don’t have the six dollars site fee. If we camp with you maybe we won’t get caught.”

The camp manager was a small, frail elderly woman.

“But why don’t you camp wild?”

“It’s too dangerous,” these giants replied, “We might get ‘rolled.’”

We approached Spokane nervously, our first city since Seattle, and stopped several miles before entering its suburbs. Corey came over on his mountain bike. He told me that cities are legally obliged to permit camping in their parks and he knew a nice one where we could stay. We followed him the fourteen miles into the centre. From the high outskirts of the city it was hard to believe that the wooded valley below hid a high-rise metropolis of hundreds of thousands of inhabitants, only revealing itself as you descend.

We arrived at our peaceful city park and as the sun went down it was hard to convince ourselves that we were not taking part in some real-life Camberwick Green. Firemen would soon come and rescue a meowing kitten from a tree, and a cute little train would chug-chug round the corner. There were the usual joggers, picnickers, aerobic walkers and cyclists. Then out came the dog training class, oblivious to all but their furry companions. As the trainer barked out her orders, cheerful white-haired ladies carried chairs to a spreading cherry tree and sat in its shade to listen to the points of their club’s Annual General Meeting. The sun slipped, darkness fell, friendly disbandment took place and all was tranquillity.

I drifted into contented sleep, dreaming beautiful dreams of ageing into one of those inspiring, energetic, silver-haired ladies.

At midnight loud firecrackers shattered worryingly close to my tent until the offenders ran off at my angry emergence. I slept again until woken at dawn by thunderous rain. After several minutes I became confused by its regular repetitious nature. Cautiously I peeped out. I was camped directly over an automatic grass sprinkler. Everything was soaked and I was lying in a lake.

The next day was a hard one. My unfit body was finally reacting against its demanding new routine and protesting that ‘OK! Fine! But enough is enough and now it’s time to go home.’ The miles were long, my lassitude total. Fortunately we found a nice bike path which took us all the way from Spokane to Coeur d’Alene. As we stood there straddling a junction, uncertain which direction to take, a car pulled up, the driver checked our problem and immediately drew off with strict orders to follow the car.

And so we met Linda. Sad, ‘crazy’ Linda. In the three days we stayed with her we were never sure how much of her wildly erratic and eccentric behaviour was due to her natural eccentricities and how much to a neural condition. After seventeen years of marriage her husband had abandoned her. He could no longer cope with the public embarrassments caused by her behaviour and was about to take off for Saudi Arabia with their teenage daughter and his girlfriend.

In this town of pastels, sneakers and immaculate casuals, Linda walked out with her jogging trousers ripped up to her knees and with large ragged holes elsewhere. This indication of her rebellious and liberal mind was misleading however — on seeing the only punk in town, she announced:

“My god, I’d kill any daughter of mine that went ‘round like that.”

With her friend Melanie, we were dragged off to the lake in order to satisfy Linda’s urge to jump in. Reluctantly, Melanie, Jill and I jumped into the icy water.

“Well come on then,” we shouted, “you were the one who wanted to do this!”

“But — I can’t swim,” she whimpered and remained firmly land-bound as we shivered, soaking, back to the house. Back home she donned one red shoe and one blue shoe, pushed us into the car and headed for town: “We’re going to eat!”

Armed with her cheque book, she bought us pizzas in the Pizza Hut (where she walked out with five plastic cups hidden between her thighs), ice creams in the ice cream parlour, burgers in the burger joint, and sweets and shakes in the confectionery. Only when we had a sit-down demonstration were we finally able to stem this gluttonous extravagance.

We were told that before we left we had to go over the border to Canada, we had to go white-water rafting, and we had to meet Linda’s adorable daughter.

So we did go to Canada (the incredible street murals in the border town made this a well-rewarded trip) and we did go on a drunken white-water debacle. When we finally got to meet her daughter we encountered a surly, rude child who deserved to be left to her fate in Saudi. As she got into the car with her father and his girlfriend, Linda stood in front of her floor-to-ceiling windows, pulled down her knickers and mooned her large, flabby, white bottom to the outraged group.

The following day, massive rows took place on the telephone over the incident. The daughter had been humiliated and embarrassed. Linda grovelled, whined, apologised. With tears in her eyes she passionately declared her love for her child and begged forgiveness. Suddenly, her face brightened, her eyes twinkled and all vestige of remorse vanished.

“Yes… but… what did they say when I mooned them?” she asked. And with that she doubled up in an uncontrollable fit of giggles.

BIG HOLE BATTLES

The road became smaller and quieter as we progressed southward following the valley of the Bitterroot Mountain Range which lay to our right. Whilst lacking the grandeur of peaks and great mountain vistas, it encompassed such a variety of miniscapes that it was endlessly interesting and comforting.

This was also Chief Joseph territory. The Nez Perce had hunted here in the summer months and had passed this way in their flight to Canada. Lewis and Clark had also passed this way crossing the Lolo Pass with great difficulty in their search for a cross-country route to the west.

Thomas Keneally writes that it is dangerous to think of an old country as new — the New World is only so from a white perspective. Many would justify the displacement of native societies by white invaders as part of a continuing process — arguing that they were only doing what American Indians had themselves been doing for hundreds of years beforehand. One result of the belief of America’s newness is a need to create history — white history. Pre-1492 is not white, therefore it is often not recognised as history. Only with the first symbolic step of Columbus’s buckled shoe upon its shores, was America born. For the American north-west, history started much later with Lewis and Clark.

An indication of this need to emphasise their own history is the plethora of historical markers which are scattered over the landscape like confetti: ‘Lewis and Clark stopped for lunch two miles down the road.’ ‘Clark pulled a hang-nail on this mountain.’ Well, okay, I’m exaggerating, but not by much.

I wish I could have been a member of their incredible expedition in 1804/5 as they struggled to find a way to the Pacific coast. Seeing landscapes and tribes unpolluted by white intrusions; coping with forests swarming with grizzlies and choked with undergrowth; sweeping down rivers; battling under, over and through mountains.

Even tamed, the Bitterroot Valley is still exquisite. Grasslands, meadows, wetlands, ponds, creeks and forests mingle in irresistible lushness. Buzzards and golden eagles soared and the vivid little bluebirds made their first appearance. They would accompany me most of the way to Mexico. Wherever there were roadside fences they hopped and fluttered ahead of me, the electric blue of their plumage flashing in the sunlight. My winged companions were always a constant delight and their dynamic company never allowed loneliness to invade.

This was horse country. Horses were everywhere — strong, short-legged and deep-girthed quarter horses. Weekend rodeos are still popular events and great fun; the loose skills of single-handed American riding contrasting sharply with the stiff back formality of the English rider. Weekend cowboys or not, the competitors rode as one their mounts, wheeling and skidding as their horses responded to the lighter touch.

The second treat of the day was coming across the most fantastic roadside stall. Combined with the familiar bric-a-brac were the added excitements of saddles, bridles and a myriad of unidentifiable leather goods which I longed to possess. And there were knives: penknives, flick knives, Bowie knives, survival knives, skinning, gutting and splicing knives. And guns of course! I have wanted a rifle since I was a teenager, and in Montana I wanted not a rifle but one of those handsome weapons of the Old West; one that my hand fitted snugly around as it slotted smoothly into its leather holster.

Whilst I disagree with the rights of all citizens to carry arms and with the arguments against control, I fully understand the resistance to disarmament. Those that say they need guns to protect themselves and their families are deluding themselves; they are merely trying to present a logic — where there is no logic — which is acceptable to modern society. But it is not a matter of logic. In reality the white history of America is the gun, and Americans are joined with their weapons at the heart, not at the head. They love their guns!

At the start of the hunting season not only do the urban cowboys prove their manhood when they make their ritual annual trip to the hills with their pick-up, their six-pack and their rifle, but they also make the backward psychological link to their ancestors who fought and struggled to maintain a stake in the land.