11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Naomi is haunted by a troubling secret. Stuggling to come to terms with her husband's death, her biggest dread is finding out that Adam knew of her betrayal. He left behind an intimate diary - but dare she read it? Will it set her mind at rest - or will it destroy the fragile control she has over her grief? Caught by the unfolding story, Naomi discovers more than she bargained for. Adam writes of his feelings for her, his challenging career, his burning ambition. How one by one his dreams evaporate when he is diagnosed with a degenerative condition. Motor Neurone Disease. How he resolves to mastermind his own exit at a time of his choice...but time is one luxury he can't afford. Soon he won't be able to do it alone. Can he ask a friend, or even a relative to commit murder? Adam's fierce determination to retain control of his own body against insurmountable odds fills his journal with a passion and drive that transcend his situation, and transfix the reader. A startingly clear - sighted and courageous story, this novel explores the collision between uncomprimising laws, complex loyalties and human compassion. REVIEWS There are few novels which deal with the issues of contemporary medical ethics in the lively and intensely readable way that [these] do.- ALEXANDER MCCALL SMITH

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 708

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

HAZEL MCHAFFIE trained as a nurse and midwife, gained a PhD in Social Sciences, and became a Research Fellow in Medical Ethics. Her success in the field has led to her being invited to lecture around the world. She has published almost a hundred articles and books in the academic world, the last of which, Crucial Decisions at the Beginning of Life, won the British Medical Association Book of the Year Award for 2002, one of the most prestigious awards in medical publishing. Her move into fiction has represented a culmination of her far-reaching medical knowledge and her literary talent.

Praise for Hazel McHaffie’s medical novels

There are very few novels which deal with the issues of contemporary medical ethics in the lively and intensely readable way which Hazel McHaffie’s books do. She uses her undoubted skill as a storyteller to weave tales of moral quandary, showing us with subtlety and sympathy how we might tackle some of the ethical issues which modern medicine has thrown up. She has demonstrated that hard cases make good reading. ALEXANDER MCCALL SMITH

McHaffie accomplishes something of great value for the reader – something deep within the ethical and far away from the bio-ethical. She exposes the potential for authenticity within intimate human relationships. THE LANCET

From Tolstoy to Cronin, writers have raided medicine in search of the raw material of literature. How appropriate that Hazel McHaffie should be repaying the compliment by using fiction to help us grapple with the ethical dilemmas so often and so effortlessly conjured up by modern medicine. GEOFF WATTS, WRITER, JOURNALIST AND BBC PRESENTER ON SCIENTIFIC AND MEDICAL TOPICS

McHaffie’s books are skillfully written to bring out the complex ethical issues we as doctors, nurses, patients, or relatives, may face in dealing with difficult issues… These books are a welcome development of what has been called the narrative turn in medical ethics. THE BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL

Hazel McHaffie illuminates the novel moral complexities of the modern world with dramatic insight… a great read. JAMES LE FANU, GP, WRITER AND MEDICAL COLUMNIST FOR THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

[The author] has woven and moulded her extensive knowledge of ethics, moral dilemmas and clinical concerns with great skill into real life, everyday, stories of drama and of tragedy. INFANT

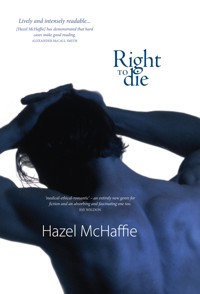

Praise for Right to Die

This is an immensely sensitive and thoughtful book. It tackles in raw and compelling detail the deterioration caused by degenerative disease, while at the same time exploring the ethical issues surrounding assisted dying. The characters are real and attractive; their pain almost tangible. This is an astonishingly authentic-feeling insight with a highly articulate and intelligent central character. SHEILA MCLEAN

This heart-rending book about a young journalist who has all to live for but is dying from Motor Neurone Disease is written with a rare understanding of the conflicts and horrors of such a death. Those who read it will understand why the law needs to be changed to allow assisted dying as an option for those whose quality of life has disintegrated and who wish to end their unbearable suffering. LORD JOFFE

Praise for Vacant Possession

Hazel McHaffie interweaves a scintillating web of medical ethics reflections into her exciting whodunit. Highly recommended both for the whodunit and for the reflections. RAANAN GILLON, EMERITUS PROFESSOR OF MEDICAL ETHICS, IMPERIAL COLLEGE, LONDON

What a tangled web! Enough angles to keep even the best ethical mind going for a week or two. GEOFF WATTS

Praise for Paternity and Double Trouble

…‘medical-ethical-romantic’ – an entirely new genre for fiction and an absorbing and fascinating one too. FAY WELDON

Hazel McHaffie, already an award winning author, has woven together authentic clinical details and ethical dilemmas with a lightness of touch that transports the reader effortlessly into the world of scientific medicine… these novels are accessible and compelling and will be enjoyed by general readers as much as by philosophers and health professionals. BRIAN HURWITZ, PROFESSOR OF MEDICINE AND THE ARTS, KING’S COLLEGE, LONDON

These two books are outrageous and you must buy them at once… Quite how the author manages to include donor insemination, child abuse, infertility stigma, genetics, surrogacy, PGD, mental illness and medical ethics into two narratively linked romantic tragedies I am not literary enough to know, but she does so in a readable, uncontrived way. JENNIFER SPEIRS, JOURNAL OF FERTILITY COUNSELLING

Right to Die

HAZEL MCHAFFIE

LuathPress Limited

EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

This novel is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events; to real people, living or dead; or to real locales are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

First published 2008

eBook 2014

ISBN (10): 1-906307-21-0

ISBN (13): 978-1-906307-21-9

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-99-1

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from Scottish Arts Council towards publication of this volume.

© Hazel McHaffie 2008

Acknowledgements

Degenerative illnesses strike fear into the hearts of most of us and learning about the effects of Motor Neurone Disease was a daunting experience. I am indebted to Dr William Whiteley, Sandra Wilson, Ann Callaghan, Carole Ferguson and the Motor Neurone Disease Association for their guidance and advice.

During the writing of Right to Die three members of my own family were fighting serious illnesses, so immersing myself in the decline of my principal character could have been overwhelming. The combined support of a wide circle of special people, too numerous to mention by name, kept me afloat and I thank them all most sincerely. They should take credit for enabling any emotional authenticity in the book.

Professor Kenneth Boyd deserves a special mention. He has managed to fit reading my manuscripts into his busy schedule for more than a decade now and I am immensely grateful for his constant encouragement and wise critique.

To the team at Luath – Gavin MacDougall and Leila Cruickshank in particular – a big thank you for believing in the product and involving me in the choices. Jennie Renton is the best editor any author could wish for. She held a kindly mirror up to my faults and then stood back while I did my own pruning. I salute you, Jennie.

Once again my two most devoted fans, Jonathan McHaffie and Rosalyn Crich, who are also my son and daughter, maintained an active interest in my writing and gave me valuable feedback. And my husband, David, tolerated my preoccupation with his usual equanimity, gave me the benefit of his meticulous eye for detail and became the invisible coffee-maker.

For Pat, who faced her own dying with such courage and faith, but chose a very different ending.

‘Murderess! Murderess! Murderess!’ Already huddled into a corner of her cell, her only retreat was to close her eyes to the condemnation.

Two rough hands reached out and jerked her arms from their protective arc around her head; ten inches away a single pair of eyes glittered with hatred. Dark brown eyes. Eyes that Adam had inherited from his mother, except that his had been liquid, soft, admiring…

‘Yes! Murderess! May you rot in hell. Eternally!’ Mavis ground out through clenched teeth.

Sharp fingers clawed the flesh of Naomi’s arms, then Mavis spat in her face and flung her daughter-in-law from her.

It was no consolation to wake from this recurring nightmare. The guilt Naomi carried during her conscious hours was no more restful than the tortures of the night. She didn’t need Freud to analyse the central role Adam’s mother played in every variation of her dream.

She threw back the bedclothes and let the breeze from the open window dry the trickles of sweat from her body. For a long time she lay staring at the ceiling, but in the end, as always, her eyes flicked to the bedside cabinet… to the plain white envelope. Even from her position on the far side of the bed, the typed instruction was clearly legible:Open only after my death.

Maybe that was why these fearful nightmares persisted. Maybe if she moved the envelope somewhere where she couldn’t see it... But then she’d never open it.

With trembling fingers she inched open the sealed flap. Words lurched on the single sheet of paper before reluctantly forming an orderly queue. Naomi read the entire page without moving anything but her eyes; even her breathing seemed suspended.

Every instinct screamed at her not to obey his instructions, not to go into his study, but clutching the paper in one suddenly damp hand, she forced herself to get up and walk down the hallway.

Do it, girl.

Open the door.

Go to his desk.

Switch on his computer.

Rows of icons glared at the intrusion. Robotically her finger on the mouse button guided the cursor.

Open folder: ‘Diary of a disease’.

Open file1: ‘The beginning’.

13 JUNE 2006—Today I heard my future collapsing. Not yesterday as you might expect – the day I got my diagnosis – but today. Curiously, it wasn’t one spectacular explosion, but a kind of defeated crumbling in on itself. The sound of… what? Twenty, thirty, forty years, just being extinguished. The authorities know exactly who’s responsible for this vile deed, but as the victim of the crime, it’ll take me a bit longer to get up to speed with the villain’smodus operandiand the consequences for the future – what’s left of it, that is. And being a wordsmith by trade, I guess I want to try to capture my reactions, exactly what it feels like here and now, before other people throw disguises over the bits and pieces that survive the blast, and before I have time to adjust to the changing dimensions of my life.

Perhaps I should have been prepared to some extent at least, but I confess I wasn’t. I was expecting to hear ‘virus’, ‘stress’, ‘after-effects of whatever’ – standard answers to a hotch-potch of symptoms. Medical-speak for ‘I haven’t a clue’. Presumably it takes time to unwire the brain from that sort of expectation and leave it receptive to a completely different message. In my case it took fifteen hours.

I heard the actual words at 4.15 yesterday afternoon. I don’t remember driving home afterwards but I do recall a vague surprise that the house was fixed in its usual place, the washing machine had finished its cycle and the clothes lay deflated around the drum waiting to be hung out on the line as if nothing had happened. How annoying. Why hadn’t Naomi pegged them out before she left for work? – in case. And I remember a feeling of betrayal that the cat wasn’t intuitive enough to know that this was one occasion when I’d have appreciated the feel of her softness wrapping around my leg, one of her full-bodied purrs vibrating against a limb still sensitised to such a welcome. Instead I got a half-hearted identity check before she closed her eyes and settled back to sleep.

I felt incredibly alone.

When I surfaced at dawn this morning the doctor’s words were written in capital letters across my first coherent thought. I fought the realisation, willing myself back to that daze of yesterday, when I was incapable of joined-up thinking, never mind anything remotely analytical or philosophical – or better still, to the blissful ignorance of the day before.

But today’s knowledge refused to be suppressed. As the blood-orange stain from the rising sun spread higher in the sky, the reality of my predicament seeped out through my restraining sandbags. So here I am; trying to take the next logical step. One thing I do know: I can’t deal with anyone else’s emotions or opinions, and certainly not their platitudes – not yet. Not until I’ve got my own ideas into some sort of order. And that won’t happen overnight. I’ve got to inch myself into this one.

I’ve always been wary of knee-jerk reactions. My phlegmatic responses infuriate Naomi at times, I know.

‘Sometimes – just once in a blue moon – can’t you get mad and scream against an injustice or a tragedy or just something that irritates you?’ she yelled at me one day.

‘Why? What good would that do?’ I said.

‘It’d let me see you’re flesh and blood, not a stone!’ She was positively spitting exasperation. I could see that, even back then when I was still pretty clueless about female behaviour.

But perhaps that very habit will stand me in good stead now. Heaven knows, I need all the help I can get. Anyway, I’m going to try to apply a bit of logic to this situation. Take it step by step. Talk myself through it.

Okay. Here goes.

Point 1. You’ve had what they call a life-changing experience.

Agreed.

Point 2. You’ve got to try to get to grips with this and work out a strategy to cope with the change and live the life.

Agreed.

Point 3. First step in the strategy.

???

..………………….….

I’ve been sitting here for several minutes now. Not writing anything, staring at the screen. I put the dots in just so the machine would know I was still there, still ‘active’.

I never saw myself as a coward. Last week if somebody had challenged me to say what I would do in these circumstances, I’d have been pretty confident I’d be strong and practical and just get on with it. I am one of life’s copers. I don’t do hysterical. I don’t do maudlin. I don’t do ostrich.

First illusion shattered – well, maybe just cracked.

Point 4. I have to get over or around or underneath this block.

But how?

I know. I’ll pretend it’s a column for the rag that pays my wages. Just the usual Wednesday scribble.

First draft:Adam’s Analysis

I’ve always hated that expression: today is the first day of the rest of your life. So hackneyed. But today – the day after my diagnosis – I felt the truth of it. Nothing will ever be the same again. My face has been pressed up against my mortality, its filthy stench has been forced into my nostrils, its grit has grazed the corneas of my eyes. Whichever of my senses I use, the stimuli I process will be tainted by the effects of yesterday’s encounter with destiny.

Okay, I know we’re all on the road to death but this is like getting into a souped-up machine with no brakes and teetering on the brink of a one-in-three gradient with no escape routes and no emergency services standing by.

How do I personally feel?

I feel as if I’m lying flat on the floor with an entire building crushing my chest. Whichever way I swivel my eyes it’s pitch black. I know they say (who exactly are ‘they’?) once the shock wears off, the ceiling lifts. It’ll have to lift a bit if I’m not to suffocate to death this very week. But the brutal reality is, this particular ceiling isn’t ever going to lift very far. Even on good days I know it’ll be there, lurking like a malevolent presence. I can’t go back to the illusions of babyhood; thinking that if I can’t see it, it doesn’t exist. Speaking of which, we had a geometry teacher, Mr Fuggins, (yep, that really was his name) who used to prove to us with step-by-step logic, that if a cactus flowered in the desert and nobody saw it, it didn’t flower; that a yellow canary was actually blue; or that two and two equalled five. I never could see the flaw in his arguments and it was an ongoing insecurity in a troubled adolescence.

Anyway this thing is there and not even Fuggins, long since gone to argue philosophy with his Maker, could magic it away. Worse than that, it’s actually coming towards me – in tiny increments maybe – but the general direction is always down, never up. There are no heroic firemen out there who’re going to rush in and shore it up at the eleventh hour. I’m not going to be able to gather one superhuman burst of power and energy and escape from this particular collapsing building. And I don’t believe in an interventionist God.

It will come down.

I will be trapped inside it.

Nobody will rescue me.

Given that inexorable fact, what am I going to do to distract my attention while this happens? And how will I spend my life – what’s left of it?

You hear of people who know they have x minutes left before a bomb goes off, or a vehicle bursts into flames, or they drown. People say their whole life flashes before them. But what about when the countdown is longer – weeks or months – or even years? You can’tkeepflashing back. I mean, evenI’dget bored with that number of replays of my quite unexceptional life up to now.

Okay, I know there are saintly souls facing death who dedicate their lives to doing something altruistic. Carrying out daring stunts. (Nothing to lose really if your days are numbered anyway, says he, cynically.) Raising stacks of money for good causes. Establishing help-lines to encourage other people going through the same tunnel. Is that the sort of thing I want for myself? I don’t know. Not yet. I have no perspective on this thing yet.

But one thing I do see, even at this early stage. I’ll have to measure my life in other terms now. The question is, what terms? What really matters?

A sudden leap of fluff from the floor made Naomi startle. The pale blue-grey hair slid silkily through her fingers as Noelani curled onto her lap.

‘I know. I know. You can’t work it out. He’s gone but he’s here. Me too.’

Slow tears dripped into the forgiving fur as her breath caught unevenly in her throat. It was like listening to Adam’s voice again. His presence seemed to be curling out of the screen, pervading the very air in the room. His fingers were on the mouse, warm over hers.

‘Oh, Noelani. What are we going to do without him?’

The wide eyes of the Persian stared back unblinkingly. The breed had been her choice, the name Adam’s.

‘Why on earth Noelani?’ she’d asked.

‘It’s Hawaiian for beautiful one from heaven,’ he’d grinned.

‘And since when did you know Hawaiian?’

‘Since yesterday. Got it out of a book of names. Nice choice though, huh?’

Noelani was certainly beautiful. With all the elegance of her pedigree but all the common sense bred out of her. More heavenly than earthly – he had a point. And she was indisputably his cat; his study was her territory, she shadowed him more assiduously than any private eye.

Naomi shivered and resolutely turned her back on the haunting emptiness. She made herself back-track through the text to mention of her own name. The incident had remained in her memory too. They’d only been together a short while then. She’d been fuming about the iniquity of a group of suburban housewives campaigning against a hostel being proposed for their street. Adam had listened to her ranting with a bemused expression on his face, and then shrugged his shoulders without comment.

‘Have you been listening to a word I’ve said?’ she’d flung at him.

‘Yes.’

‘And?’

‘And what?’

‘Well, what do you think?’

‘About what?’

‘These bigoted, privileged housewives, of course!’

‘You’ve said it already.’

‘But what doyouthink?’

‘It’s life. The not-in-my-backyard syndrome.’ He’d actually flicked his hand dismissively, fuelling her rage.

‘But don’t youcareabout these deprived kids?’ She’d glared at him.

‘Yes, of course I care.’

‘Well then?’

‘Well what?’

‘Well – why don’t yousoundlike you care?’

‘What does caring sound like? Screaming and shouting? What good would that do?’

‘Like me, you mean?’

‘Each to their own. But I don’t personally go for the hysterical approach.’

It had been the last straw.

‘Sometimes – just once in a blue moon – can’t you get mad and scream against an injustice or a tragedy or just something that irritates you?’ she’d yelled.

‘Why? What good would that do?’

‘It’d let me see you’re flesh and blood, not a stone! That’s what. Oh, you are the most maddening creature alive!’

She’d stormed out of the room and thrown washing into the machine before venting her frustration on the unsuspecting roses. The harsh pruning had actually resulted in a vigorous new growth and an abundance of flowers that summer. A happy summer. Happy because they’d committed themselves to being together for the long haul. Happy because their lives were good – fulfilled, healthy. Happy because they had plans for the future. Shared plans.

Summer was always her time of year. She was like an addict deprived of her supply in the melancholy months of winter. Even her mother had teased her that she was a foundling stolen from a tropical desert island.

It was summer now too. Its warmth stole uninvited into Adam’s study, its golden light reflected off the edge of his screen. But this year it was an impertinence. Howcouldthe sun shine? The whole world should have remained shackled to winter.

She jerked the screen crossly to shut out the oblong glare. In the sudden opaqueness behind her fingers she had a sensation of Adam reaching out to her. He’d told her once: ‘I’m the wound; you’re the cry of pain.’ It bound them together in the struggle. If she could only touch him now! Since he had gone beyond her reach she had begun to realise how much touch had meant in their relationship – the easy incidental brushes of close proximity, the spontaneous reaching out of everyday affection, the intimate exploration of passion. Her body was his; his body was hers.

She closed her eyes, willing him to stay, wrapping her arms around herself, hugging the illusion before it faded… as it always did, leaving her free-floating, bereft.

She reached out instinctively. The reflection on the screen approached… retreated.

The cat looked up reproachfully before closing her eyes and settling back to sleep across Naomi’s legs.

14 JUNE—Yesterday was another shattering-of-my-illusions day. What a pitiful output! This is me, a professional writer, for goodness’ sake! Words are my currency. They’ve kept me in my favourite brand of port; financed the holidays; paid the mortgage since I was twenty-four. Ask me to write a column on… I don’t know –custard!– and I can find an angle that’ll have you smiling, or make you think, or just force you to dash off a response. And when you’ve got editors breathing down your neck every week you have to think laterally, quirkily. No mileage in telling Joe Bloggs what he sees and knows without any help from his friends.

So here goes!

I’m picturing my mind like a bag made of stretchy fabric. Sexy silver Lycra – why not! It expands to accommodate thoughts as they come in. It sags when I’m not funnelling new stuff into it. Nobody likes flab. I certainly don’t – hence all those hours at the pool and the squash court. So I’m going to set myself a target.

Resolve 1: Keep the bag expanded. Don’t let it deflate whatever happens to the old carcass.

Resolve 2: Keep the ‘I’ in MIND. The real me. The logical, rational, thinking me. The essential Adam Willoughby O’Neill. (Thirty-eight years on I’m still trying to forgive my father for my middle name.) It’ll be symbolic of my mental attitude. If the bag stays nice and rounded, so will I be. As long as I retain my identity this thing hasn’t beaten me.

Writing ‘MIND’ inches me towards my goal. Take the ‘I’ out of it and what have you got? MND. MND. Shorthand. For a disease. A disease which I have. I don’t want it, but it’s here to stay.

MND. Motor Neurone Disease.

What do I feel at this exact moment, acknowledging that?

Strange. Nothing in particular. Presumably that’s because it’s just so many letters. I haven’t really owned it yet. I’m not really inside it.

Hmm, let’s go back to when I first heard it.

Was it only two days ago? Seems like two hundred years. I was still in work mode then. Adam O’Neill, investigative journalist, columnist, would-be novelist. Researching my material. Amassing facts.

What’s MND – exactly? What’s the treatment? How long have I got? What will happen? What are the options? I was inside my professional armour. The facts weren’t for me the man, the patient; they were for my column. Fire away. Ask the relevant questions while you have the expert captive.

And today? Yep. Sitting here consciously absorbing it, it’s a totally different kettle of fish.

MND. Motor Neurone Disease.

It’s a life sentence. Okay, now we’re talking my language. Letters, words, sentences. A sentence. A life sentence. I could write a satirical piece on that. *(Transfer to Ideas folder later) But not now. I mustn’t let work deflect me from today’s goal.

In spite of the pain Naomi felt a smile twitch the corners of her mouth.

‘Trust you, Adam!’

Even in the midst of his personal hell he’d clung to his habits. Free-falling through horror he’d seen the potential to turn his own agony into literary gain.

‘I told you! You were never off-duty!’ She wagged her finger at the screen.

How often it had happened. The notebook and pencil would suddenly appear in a restaurant where they were supposed to be enjoying an intimate dinner, or she’d find him behind a pot plant scribbling instead of mingling at an art exhibition, or she’d half-wake in the night to find him sitting up in bed committing his ideas to paper before he could go back to sleep. Writing was in his blood. His antennae were always alert for a story, an unusual take, a way in to an opinion. Even, it seemed, facing his own disintegration.

‘Come back! All is forgiven. Oh Adam. Adam. How could you leave me?’

A life sentence. No reprieve. No cure. That’s why it’s ‘life’. There’s no prospect of a stay of execution hovering on the horizon, nor even just out of sight. Dr Devlin admitted as much.

Devilish Devlin. What a glorious name for this man who announces banishment to hell. It conjures up this cartoon neurologist poking his pronged fork into a cowering patient.

‘But it doesn’t mean you can’t go on living a good life – maybe for some considerable time,’ he said, rather too quickly, I thought. Better-throw-this-drowning-man-a-lifebelt sort of reaction.

Okay, let’s look at that jolly little promise.

‘A good life.’ What’s that when you unravel it and look at the components? Who knows? All things to all men, I’d say. Is my idea of a good life the same as his? What happens if I don’t like this so-called good life? Will my own idea of what’s good change as I start to feel the tentacles tightening? Funny how many different metaphors for this thing are coming to my brain. *(Metaphors of illness– transfer to Ideas folder).

Will I end up…?

No, I don’t want to go there. Not yet. Not today. I need to pace myself.

‘For some considerable time.’

Of course, I instantly asked him, ‘Meaning? How long exactly?’

‘We can never be exact about these things. Medicine isn’t an exact science,’ he said.

Literary philistine.

‘Well, give me a scale. Some idea.’ I wasn’t going to let him sneak out of the hole he’d dug that easily. ‘Average time.’

‘Average? Two to five years. In Scotland something like ten per cent of patients live for five years. But of course some patients have been known to survive over thirty years.’

A second lifebelt. Thrown a second too late. Hey, hang on a minute! A lifebelt? More like a concrete block!

Which is worse: contemplating having only two years to go or knowing that if I’m ‘lucky’ I might spin this out for over three decades? I ask you! Imagine being slowly extinguished by this creeping disintegration forthirty years! No, I don’t want to – Iwon’t– Irefuseto imagine any such thing. I’m in control here. It’s down to me to make damn sure no such thing happens. But that’s for another day. First look at the shape of the monster; then consider the weapons;thendecide on the strategy.

So what does it look like, this new enemy? It’s a bit like a piece of writing. It isn’t defined by a full stop – not yet anyway. Nobody knows just how many paragraphs and pages and chapters the book might have, what they’ll contain, but I mustn’t start writing the end before I’ve worked out the plot, thought through the sequence, identified the main characters.

Today, right now, there’s definitely a storyline: MND’s the substance of the book; butI’mthe principal character,andI’m the author – thus far, anyway. I just have to work out how the story will unravel.

Naomi leaned back in Adam’s chair staring at his words, seeing instead a sudden vivid image of his face. Her eyes went instinctively to the photograph on the mantelpiece. It had been his choice for his personal sanctum; his favourite. He was standing behind her, arms lightly round her, his chin on her shoulder as they paused for his brother to capture that relaxed, informal moment. Four years ago. Before it happened.

She stared at the picture. His broad smile was so carefree, so happy. His skin was toned, bronzed, smooth over the strong muscles. He exuded health and vitality. She could feel the warmth of his firm embrace, his hand surreptitiously glancing against her breast, the whispered intimacies sweet in her ear.

The emptiness around her now was like a vacuum pumping the reason for her existence out of her body, leaving her light-headed.

Other images invaded her mind. Uncaptured. Unwelcome. Only partially buried. The ‘after’ images. The shadow in his dark brown eyes exaggerated by the frown drawing his eyebrows together, the right one quirked unevenly above the left. The signs of inner tension: that slightly-too-white crown on his left incisor that had broken the evenness of his smile ever since his climbing accident, clenching down on his lower lip; the restless hand suddenly combing through the wiry fair hair; the involuntary pressure of two fingers against his temple. The naked look she sometimes saw when she took him by surprise. The ragged jealousy when he’d suspected she and Brendan were…

All the doubt, the suspicion… had he recorded it? What would his diary reveal? Dare she read on? Once out, the messages could never be taken back.

She had to! She mustn’t stop. Not now. Not yet. If she were ever to understand what had happened she had to really listen to him – his feelings, his thoughts. Only now, when it was too late for her to change anything, would this man allow her to see beyond the careful façade, the pragmatism, the logical arguments, the emotional control that had so infuriated her.

But could she bear it?

The persistent ache of longing settled more heavily inside her. And this was only the beginning of his story – the simple facts.

If only. If only…

I have the drawing in front of me. Devlin may be top of his esoteric tree in the medical world but he wouldn’t have made the grade at art school. No doubt about that. But he managed to make the crude sketch look grotesque enough. Ugly spiky neurones looking ready to invade a planet. Pathways of nerves like a hideously complicated underground train track. The wiring system of the human body, he called it. Like a circuit for the Blackpool illuminations. Everything connected to something. Each bit essential to keep the whole thing functioning. By the time he’d finished I had hairy tarantulas crawling on my bare skin.

‘This disease affects the nerves in the brain and spinal cord,’ Devlin said, scribbling over various bits of his drawing. I noticed he used the definite article not the personal pronoun. Trying to keep his distance, helping me to keep mine. Just now at least. Until he’d conveyed the facts.

‘The usual messages get confused.’ His pen zigzagged across the pathways. ‘And then lost.’ A straight line severed the connection with three decisive movements.

‘The muscles then start to weaken and waste away.’ The bulging onions were reduced to flat, useless strips with two strokes of his pen.

It was his suggestion that I brought the drawing home, as an aid to breaking the news to my family. It’s just as revolting here, in spite of – maybe because of – its amateurish execution.

The spinal cord is particularly repulsive. In his doodling while he talked, he kept tracking around the skeletal outline and it has assumed all the dominance of a serpent rearing its head to inflict a mortal blow. Speaking of cord – as in spinal – I always want to spell that ‘chord’. As in co-ordination of sounds, harmony. Only now there are some discordant notes sliding in without invitation here, so perhaps ‘cord’ is better. As in knotted rope. Noose. Stranglehold.

In the privacy of my study, staring at that sketch, I’m suddenly aware – at a kind of visceral level – of the cruel irony of my situation. Communication has been such a core thing in my life. Words, thoughts, ideas, literature, writing, reading – the components of communication – are central to my professional as well as my personal life. But at this very second my physiological self is losing the knack of communicating effectively. Okay, maybe I’ll retain the power of speech for some time – perhaps even until the end. Who knows? Depends when that end is to be and how much say I have in determining it. But one by one the switches in my internal wiring will be flipped off. It’ll eventually be blackness personified in there. My only hope is to keep all the lights blazing in the upper storey.

I wanted to drag my eyes away from that slow but systematic ‘weakening and wasting’ of the muscles. But somehow I couldn’t.

‘Usually the hands and feet. But sometimes unfortunately the mouth and throat. Depending on the type.’

Before I could start to get a grip on this new nightmare scenario, Devlin was dragging me deeper into the swamp.

‘If the lower motor neurones are affected, the muscles become weak and floppy.’ He let his own hand hang uselessly. ‘But if it’s the upper neurones, the muscles become weak and stiff instead of supple. It just depends.’ His fingers assumed grotesque contortions.

‘And in my case?’ It came out just as if I’d asked, ‘And the next train, what time’s that?’

‘In your case, you have the most common form. We call it amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Usually referred to as ALS.’

Common?Don’t you call me common, matey!

‘Which in real terms means?’

‘Both upper and lower motor neurones are affected. That means stiffness and weakness. We usually see this type in older patients – the over fifty-fives. But in your case…’ He shrugged. ‘Well, it’s just one of those things.’

I couldn’t even begin to go there so I rushed off in a different direction.

‘What causes it?’

‘We don’t really know. There’s a lot of research going on, and we now know a whole lot more about the disease itself and the way motor neurones function. But very little about why it happens.’

‘Very little. So you know something.’ Do you get paid for procrastinating in your job?

‘Well, in about one case in twenty, there’s a family history of the disease. We presume that in these instances there’s a genetic origin. And we’ve actually identified the gene responsible in about one in five of this small group of familial cases – there’s a mutation of something called the superoxide dismutase 1 gene – known as SOD-1. Rather aptly named, I always think.’ Wow! This guy’s human somewhere underneath that austere façade! I like it. ‘But it’s not genetic in your case. And quite how many people in the non-familial group have gene mutations we simply don’t know.’

‘So, are you saying you have absolutely no idea what causes it in the vast majority of cases? Apart from the sodding variety.’

‘I’m afraid so. Scientists, researchers around the world are searching for answers as to the possible causes. There are all sorts of theories.’ Another eloquent shrug.

You’d have thought I had enough natural curiosity and personal investment here to be soaking up what he had to tell me, but he might as well have been speaking Swahili. Free radicals, excess glutamate, deficient neuronal blood supply, slow viruses. I heard a few of the words but they went no further than my eardrums.

What does it matter anyway? It doesn’t change a thing. There are more important things to focus on.

‘So what can you do? What’s the treatment?’

‘We can offer you treatment but I’m sorry to say, not a cure. We’ll do everything we can to ease any symptoms and prevent unnecessary complication but it wouldn’t be fair to hold out any false hope.’

Sledgehammer came to mind. What happened to softly-softly?

‘There are a number of drug trials going on and I think in time we should look at some of these and see how you feel. It’s probably not appropriate just now.’

He was right. My cup runneth over already; spare me a deluge on top of everything else.

Naomi frowned suddenly. She double-checked the dates. Yes. An abrupt end. Nothing for five days.

Odd.

19 JUNE—This past weekend seems to have lasted a fortnight. I don’t think I’ve ever craved access to my computer so much as I did over these three days. It was a form of cold turkey, I guess. My brain was still feverishly working on the text, especially in the stillness of the night, my soul searching for a forgiving receptacle, something strong enough to bear the weight of my chaos. I tried scribbling down some of the thoughts but it was too inhibiting – it’s the flow, the interconnectedness of words as well as ideas that I was seeking.

On previous trips I’ve always loved the sheer depth of the silences in that remote part of Cumbria; this time I felt as if I was being sucked through a giant pipette and lifted away from the rest of humanity for a glimpse of eternity. All that blackness. All that nothingness.

When we booked, the weekend break – pre-the-diagnosis – three nights in the Lake District, just the two of us, Naomi and me, sounded like bliss. Only a couple of hours’ drive from Edinburgh, but a completely different world. Tramping in those peaks, soaking up those views, savouring each other again. Far away from deadlines, editors and emails.

As it was, my mind seemed to reconstruct even the simplest things. How long would – no,willI be able to tramp? How soon will my view of life really start to shrink? How long will Naomi still want me? (Heavy-weight groans here! She’s just so beautiful, so utterly luscious herself.) How long can I keep my editor, or worse,Harry!from knowing my secret?

Will there come a time when even emails are beyond me?

Poor Naomi got a raw deal. I know she wanted me to let her inside the steel fences. She’s got sharing down to a fine art. And she invented comfort! But I daren’t. I haven’t staked out my exclusive territory yet, haven’t measured up the spaces she might be able to sidle into alongside me. Until I do, I have to keep everything padlocked. I know she’s getting snagged on the barbed wire trying to find a way inside for herself, but she’ll cope better with her own scratches than she would knowing I’m mortally wounded.

Sugar. Sugar.SUGAR. SUGAR!As she would say.

Just thinking about her and what she’s facing makes me want to go out and throw myself in front of the next Virgin Voyager. Just to get it over with so she can get on with the rest of her life.

The words blurred. The rest of her life. Without Adam. It was unbearable.

Sometimes even yet she forgot. She’d wander into his study looking for him. She’d come home and call to him. The realisation when it struck knocked her off-balance all over again. Distraction, hard work, sleep – nothing erased the sheer emptiness.

He was right about the barbed wire. Well, partially right. Shehadfelt the scratches but written it off as her own ineptitude. Even sensing something of his lead-lined defences she’d seen it as her responsibility to find a way to take some of the weight, not his job to hand the burden over.

The trip to the Lakes had seemed like a perfect opportunity. Away from the demands of busy lives, time to talk about this monster that had forced its way into their ordered lives; to face it together. But he’d made it perfectly plain it was no such thing. Striding up the hills, teasing her if she fell behind, quick to cut short the breaks. Keeping her laughing through dinner with ridiculous tales from work, jokes from his literary friends. At night stilling her tentative broaching with his kisses, fierce kisses that seemed to pack the longing of decades into seconds.

Through the veneer she’d glimpsed something of the brittleness, but it seemed disloyal to persist.

Naomi shrank down into herself now, recalling the sheer frustration of every speculative attempt thwarted. Why hadn’t he confided all this toherinstead of his computer? Why had he shut her out? Couldn’t he see it devalued the impact of the diagnosis on her, denying her a role.

In carefully calibrated doses she replayed the video of that weekend through her head: the manic walking, the obsessive banter, the fierce loving. But this time, through his metaphors, she saw things for what they really had been. A diversion away from the land mines inside his own barricades. For her own protection. While she slept, he was returning to look deeper and deeper into that crater alone and unaided.

In the depths of his despair he had still put her interests before his own. And she had silently cursed his selfishness.

She laid her head on the desk in front of his confession and wept.

20 JUNE—Harry’s reminders about his deadlines are really starting to rile me. 2.15 this morning I finished working on that cursed column this week. And boy, was I knackered. That tells me more than anything else how much I need to get some of this other baggage out of my system. When writing’s a struggle something’s cluttering up the space.

One thing I have decided; for the purposes of this diary of my disease, I have to forget the old literary brio and just write as I feel. It doesn’t matter. There’ll be no coven of critics circling out there ready to pounce on my pedestrian prose, denounce my implausible plot, dissect my uni-dimensional characters. If I just let it flow, this machine can be my counsellor, my confidante, my depository. That should take some pressure off.

And another thing I must record – now, while it’s fresh. Lying in bed last night, I caught myself thinking about the world going on without me. How will Naomi remember me? I need to get this right. For afterwards. For her.

Naomi shuddered and hunched herself deeper into her jacket. The sun might be staining the walls of Adam’s study golden yellow but the bleakness she felt was the colour of December.

His aloneness tore at her heart. Even now, too late, she wanted to reach out and encircle him with her love. But from the beginning he’d been standing outside her orbit, planning his solitary strategy, hiding the mental torment. Nothing new in fact. He spent most of his life working alone. She could see him yet, totally absorbed, crouched in front of the screen, not surfacing until he’d perfected each column, each sentence, each word, each punctuation mark.

‘Mr Perfectionist,’ she’d said when he’d let his meal go cold yet again. ‘You descended through the mules not the monkeys!’

‘Devil’s in the detail,’ he’d retorted, mechanically putting the food into his mouth, not tasting it; still with his writing.

She’d tested him once, slipping a hefty dose of horseradish sauce into his mashed potato. He’d swallowed it without so much as a puzzled look.

Oh, if she could only cook for him now there’d be no recrimination, no tricks. Several times she’d automatically laid two places at the table, warmed two plates, and she still hadn’t properly adjusted the portions. Every time a knife turned in her heart, robbing her all over again of appetite and purpose.

It was a struggle to return to the screen.

21 JUNE—I’ve got the house to myself tonight. Naomi’s out at some hen party, not due back till after midnight. A whole evening to write this diary. Better than any trick cyclist’s couch any day!

Part of the problem is I haven’t worked out the structure. Old Macdonald – our English teacher, not the farming legend – used to say: ‘Start at the beginning, boy, start at the beginning. Hopefully before I retire you’ll have got to the end.’ Blooming heck, the beggar went to school with Methuselah’s Dad! Way past retirement age already by the look of him. I used to have visions of him sitting swathed in that greening academic gown slowly metamorphosing into a skeleton while he waited for one of us to finish writing an essay.

Okay. The beginning.

I’ve never been one to dwell on my health; far too much to pack into life to get side-tracked with niggles and aches. But in retrospect, I guess, it started with a sort of clumsiness. I got pretty fed up with myself. Losing a game of squash against Fred, my timing a fraction out. Feeling I was in danger of falling over my own feet. Slopping coffee on my copy. Cutting myself shaving on the very morning I was meeting Kirsty Wark!

Once I started to notice it, of course, I took steps. Cut down on the caffeine. In my line of work you need something to keep you fired up. Five mugs in a day is nothing unusual, wine at night, the odd snifter of spirits later to keep you firing on all cylinders into the wee small hours. Goes with the territory. I cut back on that, too, even my all-time favourite, port.

It seemed to work; I was back in control. And it was about then that people started to notice my column. Quality stuff, the chief said. Worth missing the odd glass of Cabernet for that! He slipped extra assignments in my direction. Other editors tried to seduce me their way.

Naomi leaned back in the chair. What understatement. Adam had been like a man possessed. Snatching sleep when he must, he’d careered headlong through every day, spilling out sparkling columns and features apparently effortlessly, energy left over for working on his novel well into the night. He’d diverted her remonstrances with a lopsided grin, promising her ‘a night to remember’ or ‘the luxury of your choice with the proceeds’. And he’d more than fulfilled those promises.

‘The better the memories, the emptier the present,’ a bereavement counsellor had written in her sympathy card. Memories didn’t come better than hers.

She hadn’t noticed the ‘clumsiness’. Had she been too absorbed in her own career? Would it have made any difference if she had seen the warning signs?

I have to admit I knew I was getting stressed, but heck, we’re all living on our nerves in the media business. You need some tension to get the adrenaline rush.

I put what happened in Nottingham down to stress. Now I suspect it was an early manifestation of trouble. I was researching a piece about some kid being denied entry to an exclusive private school. Foundation for a diatribe on injustice. Boy, what a grind! The lads in that school could do with a dose of state education in an area of multiple deprivation. The parents of the excluded kid had more attitude than personality, and the headmaster was a supercilious git, so I was pretty hacked off with the whole scenario by the end of the day. I didn’t take much notice of the stairs incident.

Anyway, there I was running up the spiral staircase at the hotel after dinner. The lifts were having tantrums and I was keen to get the copy finished and forget about the morons I’d spent the day with. But half way up the second flight I was suddenly struggling. It was as if the power supply had been reduced to half. I had to lean on the banister rail and wait to recharge.

I was fine again sitting in my room typing up the story and I had an early night – well, 1 o’clock instead of 4! And I drove home in a oner next morning. Naomi left me in no doubt about the stupidity ofthatlittle aberration afterwards, but I needed to put distance between myself and the whole sorry pack of over-privileged whingers. By the time I got home I remember my arms felt stiff and my right wrist seemed oddly flabby but then, I’d been steering the mighty chariot for best part of nine hours, give or take a traffic jam or two.

So, given my ostrich tendencies, what was it that took me to the quack in the end? Being beaten at golf! I’ve always been better than Fred on the old hallowed turf. Always. Ten years now we’ve been slicing up the divots together on a fairly regular basis and suddenly I find myself struggling to keep up with him walking from hole to hole, and I just couldn’t seem to find what it takes to whack the ball for the long drives. Now that’s more than a chap’s pride can tolerate.

The GP, Dr Curtis, didn’t know me – I was going to say, from Adam. Huh! And I couldn’t really breeze in to a perfect stranger and say, ‘I want a cure for being beaten at golf!’ I warbled on about weakness and clumsiness, knowing he was probably thinking, What a time waster! But he just sat there, apparently listening, and then he overhauled the old carcass, listening to the hullabaloo inside, knocking joints, assaulting reflexes, extracting blood, asking a million completely unconnected questions. Hmmming and uhh-hhuing cryptically like a veritable Dr Cameron on a dour day.

A couple of weeks later he calls me back to say bloods are all normal, etcetera, etcetera, but he’d like me to see this guy Devlin. Neurologist. Hello? What’s up, Doc? I thought. Even I – king of hospital-avoiders – even I know you don’t get to see one of the men on pedestals unless your local witch doctor thinks you might be in trouble. I asked, casually: ‘Why?’ He mumbled on about viruses and post-viral syndromes and various incomprehensible differential diagnoses for a bit, but when I tried to extract the uncoded thinking, he was as vague as the Cuillins in the middle of a downpour on Skye. ‘Let’s just wait and see,’ seems to be the stock phrase in the medical fraternity.

I rationalised it: he didn’t want to say something incautious and have me after him in the courts. They’re all increasingly litigation-conscious now, aren’t they? And the last person you want pursuing you through the legal system is a bloody journalist! Especially one who writes a weekly column in a national newspaper, never mind a scribbler who’s getting rather well known for his perspicacious exposés!

Naomi let out a long sigh. She’d been so confident that Adam believed his theory of post-viral fatigue she’d let him go off unaccompanied to both the hospital appointments without making any effort to change his mind. Oh, she’dofferedto go with him, but he’d dismissed the need out of hand. ‘Completely unnecessary. You’ve got far more important things to do with your time than nursemaid me.’

He hadn’t mentioned the fact that the hospital had recommended he bring someone with him for the second visit. ‘They might do more tests. I’ll just take a taxi. No time to fit a court case for dangerous driving into my busy schedule this month!’

So he’d been entirely on his own, hearing the diagnosis, asking the questions, returning home afterwards. She’d been at a conference that day. At the exact moment he’d heard what was wrong, she’d been indulging in a leisurely break with Kit, with nothing more serious on her mind than whether to choose a doughnut or a chocolate éclair with her coffee.

She hadn’t touched a doughnut since. Come to think of it she hadn’t touched food much at all. Everything tasted like cardboard.

The first visit to Dr Devlin. An odd-looking fellow. Dapper, inasmuch as he’s ultra neat, every strand of hair in place, tie colour co-ordinated with his shirt, impeccable Windsor knot, shoes polished like an Army recruit’s been waxing since dawn – that kind of thing. But his right eye hasn’t been on speaking terms with his left for some time, I’d say. The minute one veers round to fix your attention the other casts its gaze to the ceiling. You do your best to ignore it but eventually it becomes mesmerising and I got confused about which one was really representing its owner. On top of that he has a nervous habit of jerking his shoulder as if the head of the humerus doesn’t quite settle neatly into the socket, or maybe he’s still recovering from carrying his golf bag over the weekend. It crossed my mind that, being a neurologist, he cultivated these eccentricities so that patients would focus on his disadvantages rather than their own problems, but I doubt it’s possible.

However, he wasn’t behind the door when brains were allocated. Smart cookie and no mistake. Only snag is, he’s signed an oath not to divulge his mighty medical musings. Sealed with his own blood, I shouldn’t wonder.

Okay, he deigned to tell me about a catalogue of tests they would do: various ‘bloods’, lumbar puncture, MRI scan, electromyography… but my uninitiated brain skipped about between the possible connections and failed to find any underlying logic. It seemed reasonable to ask what he was looking for.

‘Oh, we just need to get a better overview of how your body is functioning. Give us a baseline. Let’s wait till we get a clearer picture of everything before we start speculating about what might be wrong – if indeed there is anything really amiss.’

So bloody patronising I wanted to do something violent. But I concentrated on visualising him naked, directing traffic in Oxford Street. Seb, a journalist friend, gave me that little gem of advice when I was a raw recruit taking my first tentative steps as a reporter. Stops you taking the insults personally and possibly lowering your own standard of professional behaviour, he reckoned.

But the fact remains, his state of undress notwithstanding, I definitely didn’t like Devlin’s insinuation. I mean,me– lead-swinging? It took the combined force of Naomi and the quack to get me to agree to set foot on the medical conveyor belt in the first place.

Naomi knew he’d got under my skin and did her best to bandage the wounded pride, bless her: he didn’t mean it like that, she soothed; in these cash-strapped days, in a beleaguered NHS, nobody who expected a lucrative pension would commission all these expensive tests unless they were pretty confident there was a chance they might throw up something of consequence. Well, maybe not in quite those words! But then she realised what she’d said and instantly went into reverse and smothered me in reassurances.

Of course, back then I didn’t think it would be anythingserious; and I certainly didn’t know that there are no specific tests for MND (which was what this guy with X-ray eyes – even if they zapped independently – was already suspecting). I just didn’t need anybody suggesting I was being a wimp and wasting medical time. I think at the time I mumbled something acerbic about it being the GP’s idea to refer me to Devlin, not mine.

Anyway he’s armour-plated. Years of practice warding off the barbs of shell-shocked consumers, I guess, harden the skin. So he wasn’t about to succumb to any weapons in my little amateur armamentarium. My real frustration was that he couldn’t see I was the kind of guy who needs to have the facts pinned on his mental noticeboard. As I loitered at the door on my way out, when I thought they were supposed to ask, ‘Was there something else?’ all I got was: ‘Let’s wait and see how we go for the next few weeks.’

‘Us… we?’ How I loathe this use of the first person plural. No matter how much they think they’re empathising, they are not living with these symptoms and doubts. They will be miles away, swinging golf clubs or doing the salsa with gay abandon when I tumble down an escalator and send a little old lady to kingdom come because they didn’t warn me of the dangers. *(For Ideas folder:language of power in medicine.)

During the second visit, it was the complete opposite. Just when I could have done with blurred edges, he delivered the verdict like a judge with a black cap on his head. Even his shirt was black, relieved only by the thin gold stripe in his matching tie. It has just occurred to me that those two visits were a bit like his eyes – totally unconnected. No hint of disaster in one, unequivocal devastation in the other. A spot of time in a charm school might improve his people skills!

Funny how metaphors keep flashing into my mind. In the weeks between those two consultations, an army of SAS men were assembling stealthily behind the castle wall. Not a sound could I detect, but out of sight they were all taking up their positions, forming into ranks. On the single command of the operations chief, they all sprang into action. One almighty hullabaloo and suddenly they’ve taken over the entire caboodle, lock, stock and two smoking barrels, lifting me out of the sea of tranquillity and whisking me away to a foreign prison with glass walls and no exits. And short of shooting myself or taking my secret cyanide capsule, I’m here for the duration. *(For Illness as metaphor file.)

Of course, in fairness, Devlin and his merrie men were actually stalking in the forest gathering evidence. Their reconnoitring over those five months of tests gave them a more accurate picture of the geography and the opposition. I concede that he might have done me a favour waiting until he was sure without hinting or surmising. I just got on with my life. It never entered my head who the real enemy was. Okay, the batteries weren’t fully charged yet but eighteen-hour days and yesterday-deadlines aren’t exactly conducive to speedy recoveries from exhaustion, even for the rudely healthy. I didn’t expect a miracle cure. I just blotted out the inconvenience and turned up the volume.

So Devlin gave me five extra months of delusion.

If only Adam had shared these emotions with her, Naomi thought. How differently she would have reacted from the outset… wouldn’t she?

It had been a particularly boring conference in a lecture theatre with no natural light and intermittent air-conditioning, and she’d come home with the beginning of a migraine headache, to find Adam juggling saucepans on the Aga. His terse, ‘Tell you after dinner – just let me concentrate on getting this curry right,’ didn’t arouse any suspicion and she’d slipped away to have a long soak in a herbal bath.

The room was darkening fast as she sank into the armchair opposite him, curled one leg under her and said, ‘Right. Now tell all. What did Dr Devlin have to say this time?’

She could see him now – etched against the dying light, sitting forward in his chair, elbows on his knees, hands lightly linked, his expression emotionless. No preamble. No prevarication.

‘It’s not good news, Naomi. It’s Motor Neurone Disease. Progressive. No cure. Devlin says…’

She had stared at him blankly.

His speech was mechanical, robotic even.

As the enormity of the situation impinged on her brain she felt the stirrings of… what?…resentment. How could he catalogue the facts of his own disintegration, as if none of this would touch her? She would have to witness him falling apart before her eyes. Even as she watched his lips reciting Devlin’s words, her own mental images appalled her.

This strong, handsomeyoungman, this person she loved above any other in the entire world, would ‘gradually lose the power of his limbs’ and need ‘help with the activities of daily living – eating, bathing, toileting’…she was sitting beside his chair painstakingly spooning liquidised food into his slack mouth, one eye on the clock which persisted in ticking out normal office working hours, not the elongated seconds of an invalid’s pace of living.

He would eventually ‘lose the power to walk’…she saw herself pushing him around in a wheelchair, his emaciated body draped in an old man’s rug, grotesquely distorted limbs shouting his impotence to the staring world.

He might ‘lose his ability to communicate verbally’…she saw a quivering finger laboriously tapping out words on a keypad; heard the devastating silence of a mealtime without his crazy banter, or worse still, animal grunts spluttering through his liquidised food.

Eventually the paralysis would ‘switch off’ his capacity even to breathe…she was watching helplessly while he clutched at his throat, powerless to trade on the free abundance of air, drowning gradually in his own secretions.

‘If we let it go that far,’ Adam said tonelessly.

Shocked by the extent of her own revulsion, she was suddenly galvanised into action. Throwing herself on her knees in front of him she clutched at his clasped hands.