3,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

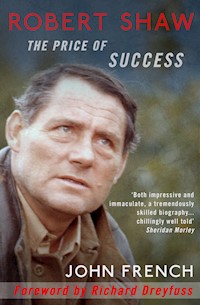

- Herausgeber: Dean Street Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Robert Shaw is most celebrated today as the Oscar-nominated star in movies like From Russia with Love, A Man For All Seasons, The Sting and - most memorably of all - as Quint in the record-breaking Jaws. His breakthrough came when Hollywood was experiencing something of a British Invasion. Sean Connery, Peter O'Toole, Vanessa Redgrave and Richard Burton were among the new stars. But Shaw was arguably more talented than any, a figure of extraordinary and wide-ranging promise. More than just a mesmerising actor on stage and screen, he was also a gifted writer. He wrote no less than six published novels (winning the Hawthornden Prize), while his plays include the acclaimed Man in The Glass Booth. The flipside to Shaw's diverse abilities was his well-earned reputation as a hellraiser. A fiercely competitive man in all areas of his life, whether playing table tennis or drinking whisky, he emptied mini-bars, crashed Aston Martins, fathered nine children by three different women, made (and spent) a fortune, and set fire to Orson Welles' house. He died at 51, having driven himself too hard, too fast, but unable to get over his father's suicide when Shaw was just 11. John French, Shaw's biographer, knew him well, professionally and personally. Robert Shaw: The Price of Success is a perceptive, sympathetic, but unsparing portrait of the blessings and curses endowing this mercurial, enigmatic and deeply engaging man. This edition features a new foreword written by Richard Dreyfuss. Praise 'Both impressive and immaculate, a tremendously skilled biography... chillingly well told.' Sheridan Morley 'I liked Robert Shaw: The Price of Success tremendously, and applaud its digital rebirth.' Robert Sellers, author of Hellraisers and Don't Let The Bastards Grind You Down

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

John FrenchRobert ShawTHE PRICE OF SUCCESS

Robert Shaw is most celebrated today as the Oscar-nominated star in movies like From Russia with Love, A Man For All Seasons, The Sting and – most memorably of all – as Quint in the record-breaking Jaws.

His breakthrough came when Hollywood was experiencing something of a British Invasion. Sean Connery, Peter O’Toole, Vanessa Redgrave and Richard Burton were among the new stars. But Shaw was arguably more talented than any, a figure of extraordinary and wide-ranging promise. More than just a mesmerising actor on stage and screen, he was also a gifted writer. He wrote no less than six published novels (winning the Hawthornden Prize), while his plays include the acclaimed Man in The Glass Booth.

The flipside to Shaw’s diverse abilities was his well-earned reputation as a hellraiser. A fiercely competitive man in all areas of his life, whether playing table tennis or drinking whisky, he emptied mini-bars, crashed Aston Martins, fathered nine children by three different women, made (and spent) a fortune, and set fire to Orson Welles’ house. He died at 51, having driven himself too hard, too fast, but unable to get past the tortured relationship to his father who had committed suicide when Shaw was just 11.

Though his life ended tragically, it is fortunate that Shaw’s biographer is someone who knew him well, professionally and personally. Robert Shaw: The Price of Success is a perceptive, sympathetic, but unsparing portrait of the blessings and curses endowing this mercurial, enigmatic but deeply engaging man.

For David Williams, who also died too

young and did not believe in heaven,

and for my son Sam.

Contents

Foreword by Richard Dreyfuss

Preface

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

La date la plus importante, dans la vie d’un homme, est celle de la mort de son père

George Simenon

You see I have thrown contempt upon your gold,

Not that I want it not, for I do piteously;

In order I will come unto’t, and make use on’t,

But ’twas not held so precious to begin with...

Thomas Middleton & William Rowley

The Changeling

Foreword by Richard Dreyfuss

Robert was the largest personality I have ever encountered.

He told the best stories. Like watching Brando do Antony in the 50’s with other stars-to-be from the 60’s, and all turning to one another silently with a look that said, contrary to all the notices Brando had had flung at him, ‘He’s genius’.

One afternoon in the sleeping quarters of the Orca, the workboat that was our ‘at sea’ rest area/equipment holder/kitchen, as we were waiting through another interminable amount of time for a sailboat to get out of our shot which could sometimes take an hour, Robert, who was in another bunk, jumped up and said ‘I know, I’ll play the ghost to your Hamlet if you play the Fool to my Lear!’

‘You got it!’ I answered, ‘but not for ten years.’

“Why?” he asked, and I said ‘Because you’d blow me out of the water any time sooner, and you know it.’

And he laughed, and laughed, and agreed.

One thing I’m sure of is that he’d lived, we’d have done it together long before this.

He was Big, Brilliant, Boisterous, a work of Art unto himself, like a cross between Beethoven’s thunder and Loki’s jokes. He terrified me and I loved him. I was his Gunga Din, sometimes to be flayed, sometimes singled out for praise.

He was the most competitive human being ever. Richard Zanuck held up shooting all day once because Robert kept beating Dick at ping pong, and Richard was the producer who let the cost of the day’s shoot slide away rather than let Robert beat him.

The day he decided to shoot the story of the SS Indianapolis REALLY drunk, became the longest day of my life, because he couldn’t do it; I was in the shot with him, listening. Everyone felt sorry for him; we were all aware that he was aware which made him drink more; finally Steven Spielberg simply waited for Robert to get to the end of a sentence, and called ‘Great! Wrap’. That was ten long hours.

That night at 3am, he called Steven Spielberg and said ‘How badly did I humiliate myself?’

‘Not fatally’ Steven replied, and the next day he did the entire monologue in one take.

Brilliantly.

One day I saw him crossing his name off a piece of paper and asked him what it was about. He explained that the play The Man in the Glass Booth that he had written had been turned into a film, and the meaning of the play had been distorted, so he was taking his name off it.

I asked what it was about, and two minutes later we were sitting in the hold of the Orca and he was explaining it was the story of a man who was either an Eichmann that the Israelis had kidnapped and brought home for trial, or he was an insane Jew pretending to be a Nazi. I think he read all of the play to me, and then he read all of the finale, a long and terrifying speech that began ‘Let me speak to you of love; let me speak to you of the Führer.’ Then it concluded with Robert saying his character’s final lines right into my eyes: ‘Children of Israel – Children of Israel, if he had chosen You, you also would have followed where he led.’

I had been entranced by all of him, the intellect, the courage of what we now call ‘the political incorrectness’; the voice, (my God, give me that voice), the art of his prose, and I awoke from that only to realize that the entire crew had been filling the portholes, listening, including Steven, as hypnotized as I. Maybe three hours, thousands of dollars; worth every penny.

He was astonishing in his acting: I thought his Claudius the best and told him and he was childlike with pleasure. No matter that this book says he wasted himself, so did all the others I worshipped that Robert thought were ahead of him: Burton, O’Toole, Harris…

I complimented him on his Henry VIII in A Man For All Seasons for which he had won an Oscar nomination; he cackled like Quint and then he told me that he’d played the part in one day.

In the morning, first, the landing of the king, off the river boat; then the leaving of the king onto the riverboat; then dancing with Vanessa Redgrave; and then the long and enormously dramatic scene with Paul Scofield. Take a look. One day. That’s what he said.

On the day I heard he’d died I drove to Steven’s house, and found him wordlessly playing the piano; I think I might have tried to speak but he was only sitting and playing, head down. For a long time. I left and drove my Mercedes aimlessly.

I was cheated out of playing his Fool. I miss him, more than even then I knew, because recently I was on an Irish talk show and was introduced to his great grand-daughter, who had never met him, and I burst into uncontrollable tears; I think because a part of me still grieves at what I could have learned, and how spectacular a companion he was.

‘Imperious Caesar dead and turned to clay...’

January, 2015.

Preface

As a biographer I have been faced with what is a rare, if not unique problem. For the last five years of his life I was Robert Shaw’s agent and for three years before that, worked for his then agent as an assistant. In preparing this book, therefore, I was faced with a dilemma. I first met Robert Shaw in Richard Hatton’s offices in Curzon Street after his return from appearing in the musical of Elmer Gantry on Broadway in 1970. Properly therefore, in the telling of the story, an ‘I’ should enter the narrative at the half-way point in the book. As this, to my mind, would have been intrusive in the story of someone else’s life, there seemed to be only one solution and that was to treat John French like any of the other characters who appear in the book, and use the third person. The introduction of an ‘I’ would have changed biography into a sort of hybrid autobiography. Hopefully this device will not appear too arch to the reader.

Immediately after Shaw’s death, some of the more sensational aspects of this book might well have appealed to the tabloid press. His sudden death was, after all, a good story. I felt, however, that then was not the time to publish. Not only would the more prurient events be taken out of context but such treatment would do nothing to explain and characterise a quite extraordinary man. The main purpose of this book, for me at least, is to explain to those who knew Robert Shaw what had gone wrong in his life and to try, for those who didn’t, to bring alive a man whose vivacity, charisma and sheer personality were unique, while documenting how this personality and its undue weight of talent came to such an untimely and unfulfilled end.

April 1993.

Chapter One

It was rumoured in Westhoughton, Lancashire, where Robert Shaw was born, that his parents had married to prevent scandal and to legitimise their son. It was not true, but it said a lot about the way the small town viewed the couple – as racy outsiders. They were certainly outsiders. Dr Thomas Shaw and Doreen Avery were married in Truro on 22 April 1926, and their first child Robert Archibald Shaw was born on 9 August 1927. Thomas Shaw was from the Midlands where his father had also been a doctor, but the family originated in Cornwall so it seemed natural for him to gravitate there after he qualified in 1924. Doreen Avery’s father, John Avery, had trained in the Cornish tin mines as a mining engineer before taking employment in the iron ore mines of Pigg’s Peak, Swaziland where Doreen was born – she was fond of telling people she was the only living ‘white Swazi’. When Doreen decided she wanted to train to become a nurse (with the intention of returning to Africa once qualified) she, too, came back to Cornwall and to Truro near to where her sister lived. It was these circumstances that brought the couple together at the Royal Cornish Infirmary where they met in 1925.

Doreen was undoubtedly a beautiful young woman. She was tall, slim and elegant, her straight back reflecting a forthright attitude to life. Her features suited the large-brimmed hats of the period. She had no intention of being cowed by social convention and openly smoked in public. She was a conquest that the flamboyant and dashing Dr Thomas Shaw – a figure straight out of romantic fiction – was keen to make. It was difficult for any woman to say no to Dr Shaw. He was athletic, tall and dark and handsome with an immense charm and apparent love of life that made his company intoxicating. Behind this charisma, however, and at first well hidden, lurked a complex character; behind the hail-fellow-well-met with which he greeted the world was a personality that was to make it increasingly difficult for him to come to terms with life.

Doreen, after his assiduous courtship, abandoned her plans to return to Africa, and they were married. Dr Shaw applied to buy various practices as a General Practitioner and eventually settled on Westhoughton where a Dr W.D. Hatton had died a few weeks earlier. It might appear that the pastoral and maritime bliss of Truro was a long way from the Northern grime and dark Satanic mills of Westhoughton on the outskirts of Bolton, but, in fact, Westhoughton in 1926 was not a town of Lowryesque factory chimneys belching sulphur into the air. It was pleasantly surrounded by open countryside and sheep farms. It had its cotton mills, like everywhere within the hinterland of the port of Liverpool and Manchester Ship Canal, and it had its coal pits, but they did not dominate the town as they did the more densely populated areas of Lancashire. Nonetheless, Westhoughton had suffered one of the worst industrial accidents of the period when the local Pretoria Pit collapsed in 1910 and 344 men and boys (before regulation of child employment) were killed.

As Oakleagh, Dr Hatton’s house and surgery was badly in need of redecoration, and in order to keep the practice going while builders were brought in, the Shaws moved into a small terraced property round the corner at 51 King Street. It was the sort of two-up two-down with a back addition and walled yard which had been built all over England to house the workers of the Victorian industrial revolution. At the back of King Street, however, was not another row of houses, but an allotment, a low-growing magnolia tree and open fields.

It was in this house that Robert Shaw was born.

As soon as the builders had finished, the Shaws took up residence in Oakleagh, a large rectangular Victorian house with extensive gardens. With the help of a resident maid and a charwoman they lived comfortably enough and between 1927 and 1932 Doreen gave birth to three more children, Elizabeth, Joanna and finally another boy, Alexander (hereafter called Sandy). Oakleagh in Bolton Road was opposite the local infants’ school, the White Horse Infant School, and the pub, the Rose and Crown, a large country-style hostelry not at all like the traditional cramped, corner of a terrace premises of Northern myth and television legend.

Oakleagh had a large front garden and Joyce Ryley, who lived across the road, remembered that sometimes in the summer, the school-teacher would take their class, including Robert, into the garden to have lessons in the sun. The Ryleys had once lived in Oakleagh themselves. Nancy Ryley, Joyce’s mother, had been brought up in the house until her father had been killed in a riding accident and their reduced financial circumstances forced them to move into the smaller cottage over the road.

Dr Shaw, she recalls, was a handsome man and a good doctor. His charm made it easy for him to make his patients feel at ease and well cared-for. ‘A cold,’ he used to say, ‘is four days coming, four days with you, and four days going.’ When he called on Nancy Ryley’s mother, whom he attended regularly into her old age, he always liked to make sure she had a good ‘nip’ to make her feel better. But the latter was a medicine he was much too fond of himself. Even to Nancy Ryley’s untutored eye there was no doubt that Dr Shaw was an alcoholic. He always carried a hip flask – ‘for medicinal purposes’ – and his visits to the Rose and Crown were many and various. Despite having a good practice he was borrowing money frequently, in an effort to hide from Doreen how much he was spending on drink, and often sat in the pub until he was forced to go home.

On the other hand he had been an athlete and was still a keen rugby player. He played rugby for Bolton Old Boys, as a guest player, and was a keen golfer. Practising his swing on the front lawn of Oakleagh sometimes led to golf balls breaking neighbours’ windows, though the good doctor’s charm always managed to defuse any acrimony.

Doreen Shaw was less outgoing. Nancy Ryley felt she was a typical Southerner keeping herself to herself, aloof, and not liking the Northern traditional neighbourliness, nosiness and ever-open back doors. But clearly Doreen had her own agenda, coping with her husband’s drinking as it got progressively worse, trying to save their marriage and bring up their increasing family. Equally clearly, as pregnancy followed pregnancy, however angry she might be at her husband’s behaviour, his persuasive charm overcame any misgivings she might have had as to the wisdom of bringing children into such an unstable marriage.

Robert Shaw was, according to another school friend, a ‘wild boy’. Oakleagh had a bay window on the ground floor with a flat narrow ledge on the top accessible by opening the sash window above it on the first floor. At the bottom of Bolton Road was a weaving mill and as the mill-girls came home up the road in their wooden clogs they would be entertained by the sight of the young Shaw wearing his father’s top-hat, with his father’s walking-stick tucked under his arm, dancing on the narrow ledge. If one of his sisters tried to join him Robert would push them back inside, concerned for their safety but not his own, before continuing the show. Nancy Ryley had said to his father at the time, ‘I don’t know what’s to be done with the boy. He’s a born actor.’

In a BBC Omnibus on Robert Shaw broadcast in 1970 he was asked about his childhood. A frisson of pain crossed his face at the question, followed by a long pause as he decided how much to reveal. His father, he said finally, he remembered drunk and sober. Sober he was ‘flamboyant’, drunk he was ‘troubled’. He used to come into his son’s room, after an evening’s drinking and weep hopelessly on his son’s bed.

Dr Shaw’s alcoholism got no better with the passage of time. It was clear to his wife that something had to be done if his reputation as a doctor and their marriage were to survive. Whatever demon was driving the doctor to drink had to be exorcised; the problem was in identifying its cause. He argued that he needed a new start, somewhere away from the pressures of medicine in an industrial environment, somewhere different, where he could change the whole pattern of his life and thus remove the need to drink. Doreen was far from convinced by this argument but seeing no alternative she agreed. They started looking for a new home.

In 1933 Dr Shaw bought a small practice in Stromness in the Orkney Islands, one of only two in the town, and the family moved into a characteristic stone house overlooking the sea. The climatic difference between Stromness and Westhoughton was marked and clearly made a lasting impression on the young Shaw, as he was to describe it so graphically in his first novel, The Hiding Place:

The clouds hung over his head like the fitted sails of a great armada, swelling and swelling, dropping and dropping, till they almost touched the ground. His mother shouted him into the kitchen closing the doors and windows fast shut. The little boy did not want to come inside, for he had never seen such stillness – the air so dense that the grass was sweating.

The social climate was different too for the young Shaw. In Lancashire he had been very much a part of school life, but at the Stromness Academy he was an outsider with a strange accent. He was a ‘ferry-louper’. His developing athletic prowess was snubbed and he was not picked for the school football team. Nor did his father’s troubles diminish, the nocturnal visits continued, his father only able to communicate his perception of the world through shuddering and pitiful tears as he knelt by his son’s bed, his face buried in the blankets.

The pattern of life established in Westhoughton soon re-asserted itself in Stromness. Dr Shaw was widely respected as a doctor but his drunkenness, in a community that was well versed in drinking, soon became a matter of public concern. With only two thousand inhabitants gossip spread quickly: the practice suffered accordingly.

At home it did not take long for Doreen to realise that hopes of a change were to be short-lived. A series of rows followed. Her husband’s pledge to her that he would cut down on his drinking had proved worthless. If anything his consumption had increased. He had a responsibility to his wife and his children yet he was treating them as if they did not exist, as if he simply didn’t care. If things didn’t improve, Doreen was going to leave, taking the children with her. Things did not. In fact they got so bad that at one stage Doreen moved the children and herself into the local pastor’s house in an effort to convince her husband that she was serious. Finally her sister, who had seen Dr Shaw’s condition for herself on a visit to Westhoughton, was consulted, and it was decided that Doreen should take the children to live in Cornwall where her sister had a farm. Three years after moving to Stromness she took her family south.

Installed in Treworyan Farm, near Ladock, in Cornwall with her sister and husband, the Cock family, things were very different for the Shaw children. Robert was enrolled at Ladock Church School which his cousins attended. With four adults and seven children, the farmhouse was very crowded. The building did have internal sanitation, but it was decided that the children should use the earth closets dug at the bottom of the garden. This was adjacent to where the pigs were kept, and the children were so convinced that the pigs would burrow through and happily eat their tender white backsides, that they would go to the toilet in twos, no matter what function was to be performed. This may have been the origin of Robert’s total lack of inhibition when it came to scatological functions – he was quite likely to invite a friend into the bathroom with him for a talk, while he took a shit.

But Dr Shaw had not given up on his attempts to reform. In 1937 he wrote to Doreen again to tell her he had a job in Keinton Mandeville in Somerset and begging her to join him there with the children. This time, he promised, it would be a new start. He would take his drinking problem seriously, he would take control of his life. Doreen saw no option but to give him another chance, and the family moved into a large family house, which happened to have been the birthplace of Henry Irving a century earlier.

Dr Shaw had not lost his ability to charm his wife, and in 1938 she gave birth to a fifth child, another daughter, Wendy. But his resolution did not last long. He was trapped, torn between his need to drink and his desire to keep his family together. He wanted children, he wanted his wife to have babies, but found it increasingly difficult to cope with them. Robert remembers being bundled into his father’s car with his brother and sisters and driven off at breakneck speed through the countryside while his father talked incessantly of things he did not understand. At the Somerset cliffs the doctor would stop, driving the car as near to the edge as he could get. ‘Shall I drive us over? Shall I? Shall I?’ he’d ask his eldest son. ‘End it all? Ah?’ It was not a joke, and, according to Robert, it happened on more than one occasion.

That same year, 1938, despite all his elaborate promises to induce Doreen to come back to him, Dr Shaw did ‘end it all’. He told his wife, not for the first time, that he was determined to kill himself. She did not believe him, as she had not on all the previous occasions. He went into his surgery and took poison. Robert was 11 years old.

Naturally enough his memory of his father’s death was confused. In one version he was at home and heard his father announce his intentions. His mother begged him not to do it in front of the children. In another he was at school, and the Headmaster of Truro School came to call him out of class. The Headmaster had been willing to drive him back to Somerset immediately but Robert had, as he recalled, said he would prefer to remain in class. In fact Robert did not enrol at Truro School until the following year. By the ’70s the story was refined still further and Robert recalled his father coming to his bedroom crying – a reprise of early events – and telling him he was going to kill himself ‘because I can bear the world no longer’. Gradually Robert had assumed the central role in the story, placing himself alone with his father’s despair. A still later version had his father drowning himself; a confusion no doubt with a real incident in Stromness when his father rescued two children from the sea. As Robert got older his feelings towards his father intensified, and they were feelings he found harder and harder to cope with.

From Somerset the family moved back to Cornwall. Using the bulk of her late husband’s estate Doreen bought a large house on the main road in Tresillian not too far from Ladock and her sister’s farm. The house, covered with Virginia creeper, had a large garden backing on to a water reservoir. At first Shaw returned to the local Ladock Church School but in 1939 his mother, using income from the rest of the estate, and from a lump sum bequeathed by her father on his death, as well as other sums of money made available by the Avery family, decided to send him to the fee-paying Truro School, first as a day boy and eventually as a boarder, for which he was granted a scholarship (which eased the financial pressures on his family).

For Shaw after 1939 and his enrolment at Truro School life was, at last, more settled. He lived in the same house and went to the same school. His athleticism developed and normal childhood pursuits were much in evidence, but there was, to anyone who knew him then, a certain amount of brooding and unpredictability that was unchild-like. ‘He was a loner,’ Elwyn Thomas, a school friend, would remember.

However, it was from this age that Shaw developed the characteristic that most of his later friends remember best – his competitiveness. Shaw wanted to win. He didn’t just like winning, it was essential to him. ‘Victory,’ he told TV Times, ‘is utterly consoling to me... the nicest way to put it is that I have a colossal curiosity about myself. So when I unearth an aptitude, I want to perfect it into a skill to be proud of.’ Equally he hated losing. Both his adult life and his childhood are littered with anecdotes about his competitive instincts and his desire to win. At Truro School he was Junior Victor Ludorum in 1943 and overall Victor Ludorum in 1945. In both years sprinting was the basis of his success.

He did not like defeat. Returning to Treworyan Farm one summer, to help with the harvest, he boasted to one of the farm workers of his prowess in running. Though the man was 20 years his elder he took up the challenge, stripped off his jacket and agreed a circuit along a country road. Though Shaw led from the start gradually the man caught up and, though Shaw was still ahead of him at the finishing line, it was a very close thing. The fact that he had nearly been beaten by a man of 35 produced a look of astonishment on his face that the friends who had been watching would never forget.

At rugby, one of the abiding loves of his life, Shaw was a late developer. He was not picked for the First XV at Truro until he was 17. But from that moment he was an exceptional player, his speed as a sprinter making him a devastating wing-three-quarter. He was good enough to play for Camborne Town, for whom he scored a spectacular try that he would recall as one of the singular achievements of his life. He would always talk about it with unbounded enthusiasm, remembering as he got older more and more detail, embellishing every aspect of the story until the number of hand-offs and dummies he delivered and sold respectively were of epic proportions. The match was between Redruth and Camborne on Boxing Day 1947. Shaw’s last account, to the Evening Standard in 1977, tells the story:

We were playing up the slope. In those days Redruth was very fashionable, and Camborne was a mixture of Camborne miners and the Camborne School of Miners, from which many Cornishmen have gone round the world. E.K. Scott was the English captain [ E.K. Scott played for England but was never captain], and he was playing with Redruth. They had a very fast wing with red hair who was called Grey. They had not been beaten for two years until we’d played them the week before and we had won. Therefore, Redruth were after our blood. It was the local derby.

E. K. Scott cross-kicked. It went a little too far, came behind the dead ball line, and I caught it before it bounced. I had played against the Redruth wing at school, and I knew I could run around him, either inside or outside. I passed him, and Scott was coming across.

I was only seventeen but I had great wisdom about games. I knew that if I handed-off Scott real hard, it would take him about five seconds to recover, and 1 hit him with my left hand as hard as 1 could, and he went down, flat!

The stand-off was called Arnold Pascoe, and he came across covering. I knew him because we’d been to the same school... We were not mugs. Never beaten in three years. Anyway, Pascoe came across, and to him it was a perfunctory tackle. I didn’t even bother to hand him off. I just hit him with my shoulder. He went down flat on his back. The one person I was worried about was the Redruth full back, who was an old miner of about 43 or 44 who had played for England and hit you like a tank. He could break three ribs with a single tackle, so I wasn’t going to take a single chance with him. I kicked over his head, and the ref was right up with the play. He couldn’t tackle me, I caught it on the bounce, and scored right between the posts.

However much this was an exaggeration of the truth the try was memorable enough to be recorded in the Camborne Centenary Programme of the 1946-47 season:

It was during the season that Robert Shaw who later became internationally famous in the literary and theatrical worlds made his debut while studying at Truro... Shaw was a fast and dangerous wing and in Camborne’s match at Redruth on Boxing Day 1947 was considered the most outstanding three-quarter. After one Redruth attack he seized on a badly directed kick to his own line and after racing about half the length of the field kicked ahead and recaptured the ball to race over for a spectacular try.

Shaw was capable of working extremely hard. If he was not good at something he worked on it until he was proficient. It was this trait, obviously attractive to his teachers, combined with his athleticism, which no English public school is slow to notice, that made him a candidate for Head Boy. In this position Shaw gained a certain amount of power, and power that he enjoyed. As he told an interviewer, ‘I didn’t like school before I was made Head Boy but the power made it palatable.’ But in this position he attracted criticism. Colin Nunn, a fellow prefect, remembers Shaw’s performance in this ‘role’ as erratic. On the one hand he was tough, not afraid to shop offenders to the masters; Nunn, himself, being a victim of punishment after Shaw reported him for attending a V.E. night dance without permission and for smoking. On the other hand he would mooch around apparently oblivious to anyone and anything, totally absorbed in a world of his own making, allowing transgressions to pass until suddenly he would snap out of it and immediately criticise a boy for some misdemeanour or other. His lack of consistency was, Nunn felt, a function of his self-absorption.

Shaw was – according to Elwyn Thomas, another school friend of the period – a philosopher, and it was difficult to get close to him. He had no close friends, no best friend. He was moody and suffered from a definite pattern of highs preceded by lows. He cultivated an unapproachfulness. There were undoubtedly depths in Shaw that the other boys saw quite clearly, without being aware of their precise nature.

There was, however, no doubt about his ability as an actor. John Kendall Carpenter, who went on to captain England at rugby, as well as becoming Headmaster of Wellington School and head of the organisation for the Rugby World Cup in 1991, saw Shaw’s talent clearly. Being younger than Shaw, Kendall Carpenter was often cast in the female roles opposite him. He remembers the 16-year-old Shaw as Mark Antony in 1943. ‘It was a great success. He had a professional command of language. His voice was abrasive but with real power.’ In later roles Shaw was even praised for his performances as Peter Pan.

But, for Kendall Carpenter, Shaw’s finest performance and his most ‘alarming’, was in Patrick Hamilton’s The Duke of Darkness playing Gribaud (the part created by Michael Redgrave in 1942), who, in the third act descends into madness:

Who am I? Why do you excite yourself sir? I am nothing. I am a thing. I am a table. I am a chair. No. I am a table. That is me. Can you not see that I am a table? Eat your food off me, sir, or you will be hungry.

Shaw was so effective in the part that he positively scared the boys in the audience. Kendall Carpenter felt the madness offered Shaw a freedom to explore areas he was already well aware of. It has long been a truism of psychology that acting is regarded as a therapy for a range of problems and especially as a means of coming to terms with trauma, and Shaw certainly had a well of emotional crises in which to delve.

Whether as a result of his success on the school stage or the feeling of command and pleasure that exercising an obvious talent gave him, by 1944 Shaw’s mind was set on becoming an actor, and, he would always add, a writer.

His early abilities as a writer are less well documented mostly due to the exigencies of war and the lack of paper for school magazines. Shaw had started to write in Stromness and his father had encouraged him, particularly impressed by one story he wrote about the survivors of a shipwreck floating in a life-raft being forced, after eating all their supplies, to eat the cook. The fact that it was the cook, the provider of food, who suffered this fate, was crucially important to the impact of the story. Shaw wrote consistently through his boyhood, was praised for essays, and frequently stated his intention to write professionally. But acting was his primary ambition. He was encouraged in it by the master in charge of drama, Cyril Wilkes. Wilkes was the typical left-wing tweed-jacketed, natural teacher encountered by lucky pupils in many English schools. He possessed the ability to inspire and enthuse the right pupil with an attitude towards learning and literature that would last a lifetime: the sort of teacher who creates the impression that learning is a two-way street and that he has as much to learn from his pupils, as his pupils have from him. To the young and impressionable Shaw, in need of a father figure, Wilkes’s talent in this regard was particularly beguiling.

But the world was at war, and there were other priorities. In common with many of his contemporaries Shaw desperately wanted to get into the war and win it for the allies. Elwyn Thomas and he discussed their future at length: the first order of business was to join the army and destroy the German War Machine, by this time already beginning to crumble. Only after this small task was accomplished would there be time to think of a career.

And the war was all too real. One morning Shaw and his brother were in their bedroom when they saw a Messerschmidt zeroing in on their house on the main road. The two boys stood at the window fascinated as the plane, unopposed by local anti-aircraft fire, headed towards the house. As it got close enough the pilot fired the guns in both wings before zooming off into the distance. Shaw swore that he could see the pilot’s face as he flew by, framed by his helmet and goggles.

Shaw’s experience of girls at this point was about on a par with his experience of warfare. He was very close to his sister Joanna (in fact so close his sister Elizabeth would describe their relationship as ‘unhealthy’) but, as for the rest of womankind, he appeared unimpressed. Florence Christie, a daughter of a friend of Doreen Shaw’s, visited the house at Tresillian regularly. Shaw, she states, was ‘not romantically inclined’. As he was handsome, in her view, with black curly hair and penetrating blue eyes, girls were keen enough on him, but the interest was not reciprocated. Moreover, there was no shortage of girls as Truro School was housing evacuees from two London girls’ schools. But the plethora of choice left Shaw unmoved. It was another trait that was to continue into later life: Shaw was never a womaniser.

The question of Shaw’s future career was raised in the family. The British Medical Council ran a scholarship to Epsom College for the sons – not, at that time, for the daughters – of deceased doctors, and, of course, Shaw qualified. Fortunately for him his brother Sandy showed an early interest in matters medical, and any pressure for the eldest son to follow the family business and take up doctoring quickly evaporated when Sandy made his intentions clear.

But Doreen Shaw was ambitious for her children educationally and there was still the question of university. An aunt had left Shaw £400 in trust but had stipulated that it could only be used for entrance to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) if he failed to get into Cambridge. Shaw had already passed Cambridge common entrance at Truro so it looked as though his aunt’s money would be applied to a Cambridge degree and not to furthering his acting ambitions. But he had a get-out. Part of the matriculation for an English degree was a special Latin examination. Shaw strode into the exam-room, sat at a desk, took out his pen, did a quick and inaccurate sketch of the invigilator and spent the rest of the allotted time staring at the walls. Thus a university degree was despatched from his life with hardly a thought and, subsequently, no regret.

Before Shaw could think of RADA, and though the war was quite obviously drawing to a close, he was still keen to join the Army. But, despite Shaw’s obvious physical fitness and athletic ability, he failed his Army medical. In his lower back two vertebrae were partly fused. He had always suffered – and would always suffer – from a nagging back pain, and this was the cause. It did not stop him sprinting, or scoring memorable tries, but it did put an end to dreams of a glorious military career. It also explained the extraordinary loping gait he affected throughout his life, one shoulder up, one dipping down, rolling on the balls of his feet with his body swaying to one side as he moved forward.

The medical shattered another dream for Shaw. Playing and competing, as he was, with current and future England rugby players, Shaw had imagined, not at all fondly, that he would one day be in the running for an England rugby shirt. With a definitive medical problem, however, there was no way that the Rugby Football Union would ever consider him for the English side.

It was a hard knock, which he brushed off with his usual ability to sublimate rather than face pain; but not being able to win, not being able to impose his will on the world, was, for him, the most difficult thing to come to terms with.

By this time it was the summer of 1945 and Shaw was 18. Even if he was accepted for RADA he could not begin until September 1946. His mother, living on investment income and working as a part-time nurse, with four children still in private education, was in no position to support a healthy strapping lad, so he applied for a job as a junior teacher at a private preparatory school in Saltburn, Yorkshire, where he lived in digs, taught English and games, prepared himself for his RADA audition and realised he was not cut out to be a teacher.

Getting into RADA would be difficult. In the intake of 1946 there would be men returning from the services who had had their education interrupted by the war, and were entitled, by right, to claim the places at educational establishments that they had gained before the call-up. This reduced the number of available places significantly and competition, for RADA in particular, was fierce.

Bearing in mind the success he had achieved with Mark Antony at school it was an obvious choice for an audition piece (a Shakespearean role was compulsory). For his ‘modern speech’ he selected Professor Higgins as a contrast.

As is often the case when provincial talent is tested against nationwide field, what was regarded locally as first class can come to be seen as only mediocre. Shaw’s audition for RADA was not a success. He was accepted, but only just.

At the age of 19 in September 1946 Shaw took up his place. He had been the Chairman of Toc H at Truro School and through that organisation was given a place in their Fitzroy Square hostel. Toc H itself was a charity bent on bringing together people of different backgrounds and providing practical help in the community. At that time it was a large organisation with hostels all over Britain. The accommodation was free but the quid pro quo was to engage in voluntary work in the area. At that time Fitzroy Square Toc H was involved with a project in the slums of Whitechapel where German bombs had made an already chronic situation a great deal worse. Shaw spent weekends cleaning and painting renovated housing, his first experience of living conditions among the poor.

Cyril Wilkes had imparted his left-wing leanings to Shaw, and it was an attitude that would stay with him all his life. Though his mother had made him conscious of his social standing and did not like him playing with the ‘common’ children, Shaw never took her snobbery to heart.

In the ’60s Shaw returned to Ladock Church School, where, after all, he had spent only a short time, to open their centenary fete. He returned to Truro School too, when Elwyn Thomas, by then chairman of the Old Boys, invited him down. On both occasions he was full of charm and chat, generous in his praise, accurate in his memory of faces, reminiscing freely, genuinely interested in the fortunes of his contemporaries. His affection for this period of his life was obvious for all to see. He took his first wife, Jennifer, to Cornwall in the ’50s and to the Orkneys and repeated these trips in the ’60s with Mary Ure. As his life became more complex his desire to recall the past did not diminish. In fact the past became almost too real.

It is axiomatic that an unhappy and traumatic childhood leaves deep scars; the past appears very much alive, very much part of the present. As Shaw got older his dreams – particularly his nightmares – and memories of his childhood became ever more vivid, ever more part of his present life. The looming figure of his father, and the image of his father’s suicide, came to be with him part of the landscape of the day. As the pattern of successive highs and lows that had already been noticed at school become more insistent, as the lows got lower and the highs more difficult to attain under the depressive influence of alcohol, the hurts of his childhood festered and grew. On the positive side, they would inform his writing, giving it a depth and perception of mortality; on the negative, they were, in combination with ‘the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’, to create a psychological profile that he found almost impossible to deal with.

Chapter Two

The RADA of 1946, in common with the rest of London, was austere. For those who didn’t experience it directly, it is difficult to imagine the extent of the bomb damage that had laid waste huge areas of the city and the slowness with which life was returning to normal. With rationing and conscription still in force and England dependent on American Marshall Aid to retrieve the economy from the brink of disaster, austerity was the order of the day. On the other hand there was a feeling of tremendous hope and vitality, a desire to make sure another war never happened again and a realisation that, with the development and use of the atom bomb, this sentiment would never be an empty echo of the aftermath of the 1914-18 war.

The victory of Clement Attlee in the 1945 election gave the young socialists, among whom Robert Shaw counted himself a member, cause for real hope and enthusiasm. At last a social charter was to be enacted that would give genuine rights to the poor. Shaw, of course, did not yet have the vote (the voting age was then 21) but talked excitedly of the opportunities that lay ahead for the Labour Government. Though he had lived in what he subsequently described as ‘genteel poverty’, his ‘poverty’ had little in common with the deprivation he would see on the streets of London and on his forays into Whitechapel. In every sense Shaw was middle-class. He had gone to a public school and lived in a large ‘posh’ house. But this did not mean he was not deeply affected by the poverty he saw. Shaw would always describe himself as a socialist. He would argue the socialist corner on television chat shows, and his subsequent wealth would not change his attitude. Indeed one of the causes of his later unease was his desire to reconcile his socialist principles with his new wealth. But socialism for him was an expression of an attitude towards people as well as a political philosophy. Shaw regarded everyone as equal. He had no time for titles, rank or seniority, whether earned or inherited. To Shaw an Irish gardener was as interesting and worthy as a captain of industry or an important writer. They would be treated the same no matter what they had done, or how much they earned.

The administrative secretary at RADA made some attempt to brighten the greyness of austerity by introducing a Rainbow Corner. By the main entrance she had set up a series of self-standing noticeboards detailing timetables of lessons and classes in bright primary colours. At this point RADA’s only theatre was in the basement (the theatre in Malet Street was as yet a bombsite), and public shows were given at the St James’s Theatre in the West End.

Shaw was, for the first time, a small fish in a big pond, and he found the adjustment hard to make. As Head Boy at Truro School he had been the natural centre of attraction, but now he was just another ambulatory student. His reaction was predictable, he was aggressive and uncooperative. He cast himself in the role of outsider. He despised the teaching methods and the organisation of RADA, describing it later as a concentration camp. It was a reaction conditioned by his inability to ‘win’.

Movement classes, when the wearing of black tights was obligatory, were hardly likely to attract Shaw who was blessed with notoriously knobbly knees. The technique classes of Fabia Drake were more to his taste. Reading some dull piece of prose, and making it in turn charming, passionate, dramatic, was a game he could enjoy. Equally, delivering Hamlet’s ‘Speak the speech I pray you...’ using only five gestures, was something very much to his taste. Other than this, his contempt for the teaching was in direct proportion to the length of time it took RADA to recognise his talent. None of his parts in December 1946 or March 1947 were more than ‘spear-carriers’ (with or without spears) and by July he was still being cast in minor roles – Cameron and Dr Coutts in A Sleeping Clergyman and Macduff in Macbeth. Things improved slightly by December when he was cast as Don Pedro and Benedick in Much Ado. But the comments on his performances during the year were not encouraging. He was criticised extensively. A ‘light nasal and high tone voice’ was noted, along with the need to beware of ‘voice mannerisms’ and to ‘see to his hair’. Comments like ‘promising’ and ‘good attack’ were hardly enough to appease his desire for success.

In a sense, of course, Shaw was not what has come to be called a RADA actor, especially not the RADA of 1947. He had a Cornish burr to his voice – which RADA worked hard to eliminate – and his back problem combined with his comparative shortness (he was 5ft 10in though he would never admit it) gave him an ungainly awkward appearance. Michael Denison he was not. In a world where the common topic of conversation was whether the acting styles of Gielgud or Olivier were to be preferred, the untutored energy and charisma of Shaw counted for little, initially. In terms of ability too, he had a great deal of competition. Among his contemporaries were many who would become successful actors: Laurence Harvey, John Neville, Edward Woodward and Barbara Jefford.

Another problem for Shaw was that the students at RADA divided into those who had been in the war and had been demobbed and those, like himself, who were too young and had come straight from school. Stories of wartime experiences made good listening in comparison to boyish pranks. And Shaw was never a good listener.

Peter Barkworth was also a fellow student and one who actively disliked Shaw’s sullen and sneering behaviour. ‘I thought he was arrogant and boastful and too like a peacock: he paraded himself in front of us and swaggered.’ But Shaw’s view of Barkworth was less hostile and at the end of class one day he suggested they go to the movies together. ‘The idea of an evening with Robert was appalling,’ Barkworth recalled, but he couldn’t think of an excuse fast enough and off they went. It says much for the film Les Enfants du Paradis that, over coffee afterwards, their common enjoyment of the film turned to mutual respect and friendship.

Not long after, Strowan Robertson, a friend of Barkworth’s at RADA, was vacating his flat and suggested that the new-found friends should take it over. He did not need to ask twice. The Basement Flat, 66 Regent’s Park Road at the bottom of Primrose Hill cost the two young men 3 guineas a week.

For Shaw it was a positive step. Toc H was very much part of school life in Truro and not living with other actors had an isolating effect. Now he had a place of his own and could feel, through Barkworth, more connected.

Shaw was a good flatmate. The flat was spartan with little furniture, an old sofa and armchair, a dining table and chairs. The two went shopping together in Camden Market and would cook meals in the tiny kitchen. Shaw read a great deal and wrote a great deal, filling notebooks with poetry. He read Yeats and Eliot but singular praise was reserved for Auden whose attitudes heavily influence Shaw’s literary efforts and his ‘quest’ for a stance in relation to life. Auden’s basic belief that man is a religious animal – in the widest sense – and his attempt to reconcile this with socialism, his positioning of himself vis-à-vis life (‘All I have is a voice’) and his opposition to Fascism (‘The best reason I have for opposing Fascism is that at school I lived in a Fascist state’) were all themes that would occupy Shaw.

On Barkworth’s birthday Shaw gave him a copy of Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives in which he had inscribed a pastiche of an Auden poem:

So I need not wish you Any sense of theatre Those who love illusion Know it will go far Never spend your shillings On a silly picture, What we never say and do And who we never are.

You have known for hours The simple revelation ‘Why we’re all like people Acting in a play.’ And will utter, Peter Man’s unique temptation Precisely centre-curtain A technical cliché.

Remember if you’re able Only the author can Change the lines and Give you the lead A silly sort of statement Is wisest in the night, what You cannot get away with You have no need.

What else shall I wish you? Shall I wish you marriage Shall I wish you lovers, money, happiness? No! for Mr Auden Recalls an ancient proverb ‘Nothing’ he says so ‘Fails like success.’

I’m not such an idiot As to claim the power To peer into the future To see how tall the lights I’m prepared to guess you Sleep best in the day-time Work most every evening And great long nights.

If I’ve ever known you May you all your troubles Carry in a suitcase In a normal way. Balance on the tightrope Cleverly combining Gusto and intelligence, Night and day.

I can think of other things But you understand me I must learn my part Bring these verses to a close. Happy Birthday Peter Live above your income Travel for enjoyment Follow your own nose.

Barkworth’s enduring memory of Shaw is perhaps unexpected. On summer days they would go over to the steep banks of Primrose Hill and he in the sun. Barkworth remembers Shaw lying on his stomach on the grass supporting himself on one elbow while he worked out a poem in an exercise book in front of his chin. To Shaw, he felt, this represented total contentment. It was true. Over and over again Shaw would speak of the pleasure of writing; a physical pleasure and a spiritual one – ‘though one cannot always/Remember exactly why one has been happy,/There is no forgetting that one was.’ (‘Goodbye to the Mezzogiorno’ by W.H. Auden, a poem he loved to read aloud.)

Another snapshot of Shaw at this period conforms better to expectation. Philip Broadley, another RADA student (later to become known as a television writer rather than as an actor), was living in a flat in which he had set up a three-quarter-size table-tennis table he had been given. Shaw got to know of this and out of the blue one night turned up at Broadley’s front door asking for a game. Broadley was an experienced player and beat him. The table was riddled with woodworm and every time a hard point was scored wood dust showered on to the floor and bits would fly off the table. They played again. Broadley beat Shaw again. They played again with the same result. Shaw went home. The next night, equally unexpectedly, Shaw turned up. Could they have another game? He was beaten conclusively again. Over the next weeks Shaw visited Broadley over and over again. Gradually the beatings were less conclusive. Then Shaw won. It was the beginning of an important friendship in Shaw’s life. It was amazing that the table-tennis table survived its inception.

These two images of Shaw, the quiet contented writer and the aggressive never-say-die competitor with the overweening desire to win, are echoes of the schoolboy: the moody self-absorbed loner as opposed to the Victor Ludorum winner and First XV rugby player. They were contradictions in personality that would run all the way through Robert Shaw’s life: the quietness always connected to writing, the competitiveness becoming attached to his acting career. They were contradictions he was never able to resolve.

Whether by virtue of his friendships and domestic situation and integrating more into the society of RADA life – no longer protecting himself by playing the outsider – or whether because tutors had begun to appreciate what Shaw had to offer as an actor, his stock in the school was beginning to rise. In February 1948 he was cast as Addlesham in This Woman Business and was commended for being ‘breezy and expressive’. In March his David Choirmaster in The Witch was done ‘very well’ and by the time of his final assessment in October 1948 the praise was almost fulsome:

He has shown signs of brilliance in some of his performances, which are inclined to be uneven... He is the kind of personality who might become remarkable in the professional theatre.

The use of the word ‘personality’ rather than ‘talent’ says more about RADA than it does about Shaw.

Peter Barkworth was less encouraging. Two people, Shaw used to tell his friends, had advised him to give up acting and avoid the disappointment of failure. Cy Endfield (the director of Zulu) and Peter Barkworth.

In discussion with his mother and aunt, Shaw had decided to take the London University Diploma of Dramatic Art. Shaw’s family had no experience of the life of an actor but imagined, rightly, that it could be extremely precarious. The Diploma was at least a qualification that would allow Shaw to teach and would therefore give him something to fall back on. Among the other students at the time only Peter Barkworth, by coincidence, took the Diploma. Both of them passed. Clifford Turner, who judged the spoken reading, felt Shaw had a ‘declamatory style, but it’s better to over-colour than be colourless.’ ‘Colourless’ was never going to be a description that would fit Robert Shaw.

Nor were his opinions pallid. Before leaving RADA Peter Barkworth had got a job at the Intimate Theatre, Palmers Green, playing Young Woodley for director David Garth. Shaw came to see the play and did not hesitate to express his unwavering criticism, delivering an indictment not only of Barkworth and the play but of the whole system. Barkworth and the ‘rest of the cast’ were using ‘a bucketful of clichés’ to convey character. ‘I suppose dogmatic methods are essential in this ghastly business of weekly rep.’ The play was overall ‘too acted’. Shaw, whatever else RADA had given him, had a well-established idea of what acting should be and what it should not be, by the time he left.

Behind Shaw’s bluff hectoring exterior there was a fine mind. He knew what represented his best interest. When Philip Broadley tried to talk him out of the part of Hercules in the Sophocles play, because he thought the costume of hard leather armour, moulded to the chest, would make a very definite impact, Shaw politely but firmly refused. ‘No boy, I think we’ll stay as we are, boy.’ (‘Boy’ was to remain his favoured and often-used diminutive.)