3,65 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Thunderchild Publishing

- Sprache: Englisch

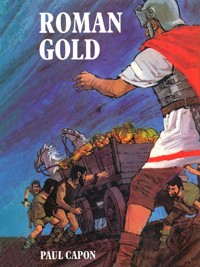

This story, set in what is now East Anglia, takes place during 449-451, after the departure of the Romans from Britain. During the Roman occupation, Mangan, a Briton, captured by a band of armed Romans, is forced to help bury several heavy treasure chests and then sold as a galley slave. Thirty years later, he regains his freedom and returns to East Anglia. But he is obsessed with the memory of the treasure which he helped to bury, and so, accompanied by his grandson, Cador, he sets out to try to find the place again so that the treasure can be used in the fight against the Huns, who are threatening to overrun the whole of Europe.

The dangers Mangan and Cador face, and the difficulties they have to overcome make this a fast-moving and thrilling story.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 156

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

ROMAN GOLD

Copyright Information

1 — Starling Woods

2 — The feast

3 — The attack

4 — Leofric

5 — Plan of action

6 — Disaster

7 — In the dark

8 — Treasure hunt

9 — The well

10 — The voyage

11 — The bridge

12 — The scourge of God

Author’s Note

ROMAN GOLD

Paul Capon

Copyright Information

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

ROMAN GOLD

Copyright © 1968 by Paul Capon.

Published by arrangement with the Paul Capon literary estate.

All rights reserved.

Edited by Dan Thompson

A Thunderchild eBook

Published by Thunderchild Publishing.

First Edition: 1968

First Thunderchild eBook Edition: November 2018

Cover and interior illustrations by Roger Payne,courtesy of Hodder & Stoughton (Brockhampton Press Ltd)

1 — Starling Woods

A STEADY breeze blew through the open door and brought with it the scent of meadows and spring flowers.

Cador had breakfasted well on sweet-cured ham and newly baked barley bread, and now felt strong enough to wrestle an ox. He flexed his muscles, and his mother, smiling, asked him whom he was planning to fight.

“No one,” he assured her, grinning. “I feel very peaceable.”

“If you’re doing nothing else, you might see if you can get us a hare or two for supper.”

“Glad to,” said Cador, getting up from the table. “Though I haven’t seen many this year yet.”

His father paused on his way to the door. “Hollybush Meadow,” he said. “There are hares by the score down there. I noticed them yesterday, leaping about as if they’d gone mad.”

“Hollybush Meadow it is then,” said Cador. “Father, would you ask old Alban to saddle my colt?”

His father nodded and went out. Cador considered putting on his boots, which were standing in the hearth, then decided that it was fine enough to go barefoot.

But his mother had other ideas. “Put your boots on, Cador,” she said. “You’re not a peasant.”

“But, mother, I never wear boots in the summer.”

“It isn’t summer yet, and in any case you’re no longer a child. You’re practically a man, and if you want to be accepted as one you must wear boots all the year round.”

Cador sat down with a good-humoured sigh and pulled the boots on to his feet. He considered them a stupid and uncomfortable invention, like a lot of things introduced by the Romans, and now that the Romans had gone, the sensible thing would be to give them up. But there was no arguing with his mother.

He said, “I might even try for a deer. Some were seen in the Starling Woods last winter.”

“Then take a sword with you.”

“For killing deer?” laughed Cador. “I’m not going to war, mother.”

“Never mind. These days a sensible man is an armed man.”

“First boots, then a sword. Good thing we haven’t any shields or helmets.”

“You can laugh, but there are some wild characters in those woods. Robbers, ruffians, murderers. Men who’d kill you for the clothes you stand up in.”

“And Saxons?” asked Cador, teasing her. “Yes, there must be a few Saxons.”

“Saxons, too, quite likely,” said his mother, grimly. “They’ll get here sooner or later, you mark my words.”

“Never. They’ll never venture this far inland. They like to keep within sight of their ships.”

“A man can reach the coast in under three hours, Cador.”

“ ‘Hours’,” mimicked Cador, smiling, and this time his mother smiled, too. Her husband had given her a Roman water-clock for a wedding-present, and ever since she had spoken of “hours” as a matter of course. The joke was that no one really understood the clock. The last person capable of telling the time by it was Cador’s grandfather, and he had vanished mysteriously some thirty years before.

Cador’s mother became serious again, and said, “There was another raid only the night before last.”

“Who says so?”

“Old Griff the drover. He got back from the coast yesterday and, according to him, the Saxons burnt down a farm and stole two horses.”

“That’s not much of a raid. In other places they’ve burnt whole villages.”

“That’s true,” agreed his mother.

“How many ships did they have? “

“Only one, Griff says. That shows how bold they’re getting.”

“Maybe. Anyway, if they do come, they’ll get a rough welcome.”

“From you, I suppose?”

“From everyone on the farm. You know that, mother. All the men are pretty good bowmen and —”

He broke off as a massive young servant-girl came into the room, then went on: “— and some of the girls could put up quite a show, too. Couldn’t they, Gwynna?”

“What’s that, master?” asked the girl, grinning and rubbing her huge red hands together.

“If the Saxons come to Kaerikken,” said Cador, “you’ll give them something to think about, won’t you?”

The girl’s grin became broader than ever. “Saxons!” she exclaimed. “Well, I reckon I could break a few heads with my pestle before they got me. Half the trouble with Saxons is that everyone is too scared to fight ’em. They’ll overrun the country like rats if we don’t stand up to them.”

“Hear that, Cador?” asked his mother, handing him his food-sack and ale-skin. “Now perhaps you’ll agree to take a sword?”

Cador laughed without committing himself, and patted her cheek affectionately. “I’ll be back by sunset,” he told her. “That is, if the Saxons don’t get me!”

In the passage he met his grandmother, and bade her good morning. She did not reply, but that only meant that she had not as yet said her prayers, and he noticed that she was making for the altar-room. “The first words of the day belong to the gods,” was her belief, and indeed she was very religious.

She would probably spend half the morning in the altar-room and Cador knew that most of her prayers would be for her missing husband, his grandfather. The rest of the family had given him up for dead, but not the old lady. One day he would come back, she said, and nothing could persuade her otherwise.

Cador fetched a bow and some arrows from the room where the weapons were kept, and decided against taking a sword. After all, he had not made his mother any promise, and it was really too hot for him to burden himself unnecessarily. Saxons! It was absurd to think of them coming to Kaerikken, and as for outlaws, well, he had a bow and arrows, and a hunting knife at his belt. He could take care of himself all right.

He stepped out into the sun-drenched yard, and his colt, fresh-groomed and gleaming as if polished, greeted him by neighing and tossing its head. He swung himself into the saddle and they were away, cantering across the front meadow at a great pace and making for the road that ran as straight as a taut rope across the countryside and which was known as “the soldiers’ way”.

It was still called that, even although forty or fifty years had gone by since last it had echoed to the thud of marching boots, or to the clatter of a troop of cavalry. The Romans had gone. Now grass grew on their roads, and their forts were in ruins. Cador had never seen a Roman, and hardly knew a dozen words of Latin. Yet he had a little Roman blood himself. His grandmother’s mother had been the daughter of a garrison-commander, and the commander had been a real Roman, born in the shadow of Trajan’s Column.

The road ran through the village which at this time of day was almost deserted. The men were all at work in the fields and the women were probably doing their washing down at the stream. A few children ran in and out between the huts, playing at Britons-and-Saxons, and a small group of old people sat in the sun watching them.

“Where are you off to, master?” cried one of the old men as Cador cantered by, and Cador told him that he was hoping to get a hare or two.

The old man shook his head. “It’s too hot for hares, master,” he said. “You should’ve been up before the sun rose.”

Cador laughed, but when he reached the Hollybush Meadow he found that the old man was right. It was too hot for hares. There was not one to be seen and in the whole meadow nothing moved except a bullock’s tail, swishing idly in an attempt to keep the flies away. The woods on the far side of the meadow seemed more inviting and Cador made for them, telling himself that deer were less troubled by the heat than hares.

It was cool and quiet in the woods, but it was also a little eerie and Cador advanced cautiously, watching for the suspicious movements in the undergrowth. He put an arrow to his bow and held it there with the string taut. He wished he had taken his mother’s advice and brought a sword, and he could not forget that only the year before a farmer had been set upon by outlaws in these same woods, robbed, then beaten almost to death.

At the same time he refused to turn back. He would not admit his nervousness to that extent, but he wished the woods were not quite so dense and so silent. The paths had become overgrown during the winter and every so often he had to crouch low over his horse’s withers to avoid being knocked from the saddle by a branch.

A wood-pigeon started to coo incessantly. It was as if it were mocking him and it got on his nerves. It seemed to follow him and presently, when he came to a clearing, he saw the bird high above him amongst the branches of an elm. He pulled up and let fly an arrow in the bird’s direction, to be rewarded by a flurry of wings beating panic-stricken through the foliage.

He had missed the pigeon by less than a thumb’s breadth, and the arrow had fallen into a bramble-bush. Its flight feathers glowed scarlet in the undergrowth and he slipped from the saddle to retrieve it. His colt started to crop the grass of the clearing and now, with the pigeon gone, there was nothing to break the heavy silence except the horse’s muted champing.

Cador forced his way into the undergrowth and gingerly parted the brambles in an attempt to reach the arrow. He scared a blackbird from its nest, and its shrill protest had hardly died when he heard a sound that startled him quite as much as he had startled the blackbird.

Somewhere, close at hand, a man had sneezed, and immediately Cador’s head filled once more with thoughts of outlaws, robbers, murderers!

He fitted another arrow to his bow, then, holding it half-drawn, moved stealthily back towards the clearing. Relief flooded through him when he saw that his colt was still unconcernedly cropping the grass.

His relief was short-lived. He was just about to go to the colt when it jerked its head up and swivelled its ears as if it heard something approaching along the bridle-path. It had scented another horse and in a flash it was gone, tossing its mane and galloping back towards the Hollybush Meadow.

Cador stayed where he was, half-hidden behind an oak, and drew his bow. Another horse was certainly approaching. He could hear the thud of its hooves on the soft turf, and the faint jingle of its bit. He realized that its rider was probably some harmless wayfarer, but at the same time he wished fervently that he was armed with something more substantial than a bow.

He peered through the undergrowth and glimpsed the horse before he glimpsed its rider. He knew every horse for five miles around, and this one was strange to him. It was a bay cob, thickset and shaggy, and, to judge by the muddy state of its legs, it had already come some way that morning.

Then he had the shock of his life. The little horse trotted into the clearing and, as soon as Cador had an uninterrupted view of it, he saw that the man on its back was a Saxon!

Cador had never met a Saxon, but he knew how they dressed and this one dressed no differently. He wore a round iron helmet and a wolf-skin across his shoulder, and the lower half of his body was clothed in loose trousers cross-gartered to the knee.

Cador kept a firm hold on himself until the Saxon was nearly across the clearing, then, as he thought of what might happen to his unsuspecting family at Kaerikken, his control snapped. He took careful aim and sent an arrow towards the Saxon’s huge back.

The arrow struck the man exactly between the shoulder-blades, but it did not bring him down. It did not really penetrate the great matted wolf-skin that covered his back, but it must have pricked the Saxon for he gave a bellow of rage that cleared the trees of birds, then wheeled his horse to face his attacker.

He was flourishing a long-bladed sword such as had not been used in Britain for hundreds of years, and Cador, glimpsing it, took to his heels.

The Saxon saw him go and followed, forcing his sturdy mount willy-nilly through the undergrowth, and Cador was within an arm’s length of death when good fortune rescued him. The horse stumbled, then fell, and its rider shot over its head to land heavily at Cador’s feet.

He moved like lightning. He brought down his foot — booted, thanks to his mother — on to the Saxon’s sword-arm and wrenched the sword from his grasp. Yet he did not forget that he was civilized, and plucked the arrow from the man’s back. Then he prodded his enemy with his foot to indicate that he might rise.

The fall had shaken the foreigner badly, and he took his time about getting to his feet. He was as huge as a barrel and by no means young. His hair and beard were streaked with grey, and Cador guessed that he was not much less than sixty. His eyes, vividly blue, were just now as threatening as storm-clouds, and he cursed Cador roundly. “You young scoundrel, you!” he growled. “You’d kill a man without warning, would you?”

“Keep your mouth shut and your hands high,” ordered Cador, then, with the point of his sword against the other’s throat, he whipped the dagger and the hunting-knife from his belt, and not until he had done so did it dawn upon him that the man had spoken to him in British as good as his own and with just the same accent.

He said, guarding himself with the captured sword, “Aren’t you a Saxon? And if not a Saxon, what?”

“A Saxon!” snorted the big man, contemptuously. “Do I sound like one? Boy, I’m as British as yourself, and I was born not five thousand paces from these woods!”

“Oh, were you?” said Cador, in disbelief. “Then, no doubt, you can tell me what they are called?”

“That I can. These are the Starling Woods.”

Surprised, Cador tested him further. “Then can you say who owns these woods and who farms the surrounding land?” he asked.

“Not for sure, but I can chance a guess. Is it a man by the name of Conan? Conan, son of Mangan?”

“Yes,” agreed Cador, nonplussed. “Indeed, the Conan you speak of is my father.”

“Your father?” cried the big man, astonished, and with shining eyes. “Then, by thunder, I am your grandfather, the very Mangan I just named!”

Cador was so excited that his sword arm shook, but at the same time he knew it behoved him to be careful. This man might be all that he claimed, might indeed be his grandfather, but he could equally well be a clever imposter. So far he had said nothing that he could not have learned from a peasant at the point of his sword.

“Tell me,” said the big man, suddenly, “does my wife, your grandmother, still live?”

“She does indeed,” Cador told him, “and no doubt you can tell me her name? “

“Most certainly I can,” said the big man, beaming like a full moon. “Her name is Ursula, and if you still doubt my identity, I can tell you that she wears a bracelet on her wrist sacred to the god Taran. Am I right?”

“Yes,” said Cador, faintly.

“I thought so. I gave her that bracelet on our wedding-day, and whatever else she may have lost she will not have lost that!”

At last Cador was convinced that the man facing him was his grandfather. He threw the sword to the ground and, taking the other’s hands in his, begged his forgiveness. “And let me pick some dock-leaves for your wound,” he cried. “It should be treated.”

“Call that a wound?” laughed his grandfather. “It is no more than a scratch, boy, a mere graze, a gnat-bite! No, I’ll stop for nothing that keeps me a moment longer from my wife and son!”

2 — The feast

CADOR’S FATHER, unlike Cador himself, needed no proof of the bearded man’s identity. As soon as he set eyes on him, he dropped the bucket he was carrying, cried “Father!” and embraced him; and when Cador’s grandmother saw the man in the helmet and wolf-skin she did something that Cador had believed impossible — she burst into tears.

Cador’s father gave orders for a feast of celebration to be prepared, and his words seemed to sweep through Kaerikken Hall like a whirlwind, creating uproar. Men and maids got busy flaying, plucking and scalding, and soon the smell of roasting filled the air. The thudding of the great pestle in its mortar seemed to rock the house as Gwynna, the head cook-maid, prepared dishes in old Mangan’s honour that would not have disgraced the table of King Vortigern himself; and the little dog that turned the spit barked so much with excitement that everyone else had to shout to make himself heard.