3,65 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Thunderchild Publishing

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

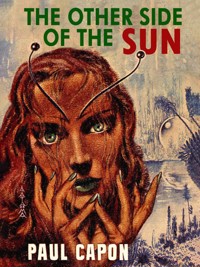

When young Stephen Craig came over from America to stay with his girl friend Daney and her father, all seemed set for a peaceful, happy holiday on the coast, with Mr. Salgado painting landscapes, Daney and Steve swimming and boating. Their weirdest dreams would have seemed tame beside the reality of what befell these three when, while swimming one morning, they were snatched out of the sea by a mechanical monster and transported by it through space.

Phobos is one of the moons which revolve round Mars — so the astronomers say. In Paul Capon's story he tells us that it is really an artificial satellite set going by the Martians — a gigantic mechanical brain which controls the automatons it reproduces.

To this nightmare world the three humans were taken, a world peopled by creatures which could perform superhuman tasks, but could not feel any emotion. What hope of understanding or pity could there be from them? How could Mr. Salgado, Stephen and Daney escape with their lives?

Paul Capon tells the story of their dangers and eventual triumph with that mixture of the factual and the bizarre which make his stories so vivid. However exotic the fantasy it always has its roots in scientific possibilities.

Paul Capon (1912-1969) was a British novelist of considerable reputation. He had over twenty novels to his credit and counted film editing and script writing as part of his experience. He traveled extensively in Europe and made a hobby of chess, book-collecting and swimming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

LOST: A MOON

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

LOST: A MOON

Paul Capon

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations,and events portrayed in this novel are either products of theauthor’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Lost: A Moon (original title: Phobos, the Robot Planet)

Copyright © 1956, 1984 by Paul Capon.

Published by arrangement with the Paul Capon literary estate.

All rights reserved.

Edited by Dan Thompson

A Thunderchild eBook

Published by Thunderchild Publishing

First Edition: August 1956

First Thunderchild eBook Edition: August 2014

CHAPTER I

For three afternoons in succession nothing happened, and then it came again . . .

Steve saw it first and pointed into the cloudless sky. “Look!” he shouted. “There it is!”

Daney sat up quickly and took off her sunglasses. Shading her eyes, she gazed up into the blue and her heart was thumping like a trip hammer. Mysterious flashes were whipping back and forth across the sky as if some vast, highly polished and almost invisible object were swinging through the air at a speed faster than the eye could follow. And the flashes were accompanied by a low, sibilant sound like that made by a flailing cane.

Steve jumped to his feet and ran up the beach for his camera. The flashes seemed closer now, and Daney had to fight to control her fear. She also rose, and she was glad when Steve came back. “Gee,” he muttered, gazing into the view finder, “I wish whatever it is would keep still. How the heck can I photograph a jet-propelled ghost?”

“I’ll go and get Daddy,” said Daney, and her voice trembled a little. “Oh, here he is.”

Her father had been painting among the sand dunes behind them and he still had his palette in his hand. He was a massive man, deeply bronzed, and the sight of him had the effect of steadying Daney’s nerves. She waved to him and somehow managed a smile. “Daddy, the flashes!” she cried.

He grinned cheerfully, and nodded. “I think they’re a bit closer today, aren’t they?” he said.

“Much.” The camera clicked as Daney spoke, and she glanced at Steve. “Any luck?”

“I don’t know . . . Look out!”

The flashes had resolved themselves into a single disk of spinning light, and this was driving straight at them. Daney threw herself down, but Steve stood his ground and took another shot. The object, whatever it was, whined through the air hardly thirty feet above their heads, then suddenly stopped, stopped dead in mid-air, so that for a brief second the three of them saw it clearly as a shining egg-shaped thing with four slender legs splaying out from it.

Steve wound the film on with nerveless fingers. “Just stay there, buddy,” he breathed. “Just stay there and let me —”

He broke off as the weird machine suddenly darted away, flashing like silver in the sunlight. It stopped again, hovered momentarily with the sun behind it, then shot off to another point, repeating the whole maneuver some four or five times.

“Keep still, for Pete’s sake!” gasped Steve, struggling to hold the object in the view finder. “Uh-uh — got you!”

He was only just in time, for a moment later the thing shot straight up into the sky, receding so rapidly that within a matter of seconds it had disappeared altogether without leaving so much as a vapor trail to show it had ever existed. Then there was nothing to be seen except the sky, the sea, the beach and the sand dunes, and the only sound was the murmur of the small waves.

Daney glanced at her father. “Well, Daddy, that wasn’t summer lightning, was it?” she said, referring to his original theory when they had first seen the flashes some days before.

He shook his head and sat down at her side. “It’s all very puzzling,” he murmured, “but perhaps when Steve develops his film we’ll learn something.” He turned to the young American. “Do you think you got a good picture, Steve?”

“Maybe, but I can’t swear to it — the darn thing darted about so much.” Almost absent-mindedly he took a shot of Daney and her father to use up the last of the film, then wound it off. “Mr. Salgado, what’re the chances of it being a new type of aircraft that’s still on the secret list?”

“Rather small, I should say. If that were the case, surely the pilot would have kept well away from us instead of hovering around close enough for us to take photographs.”

“Oughtn’t we to go to the police?” asked Daney.

“That would be all right if we had something concrete to put before them,” said Peter Salgado, “but actually all we’ve got is just one more flying-saucer story. The police would simply tell us we were wasting their time.”

“Unless we could show them a photograph,” said Steve, starting up the beach toward his clothes. “I’m going to get back and develop this film just as fast as I can.”

Peter Salgado glanced at his watch. “Well, we’ll come with you,” he said. “It’s getting on for teatime, anyway.”

Ten days had passed since the mysterious flashes first made their appearance and on that occasion Salgado was alone, painting among the dunes. He had seen the flashes far out to sea and they had made so little impression on him that he did not think to mention them to Daney until the following afternoon when she went with him to the beach and the flashes appeared again. They still weren’t near enough to be alarming, and Salgado had more or less dismissed them as an unusual form of summer lightning. “That, or an atmospheric illusion,” he had said, and Daney had accepted his observations with reserve. She hadn’t cared for the flashes, and they had filled her with a sense of foreboding that had persisted throughout the next day when she and her father went up to London to meet Steve at London Airport.

Steve was the only son of Salgado’s oldest friend, now a professor at an Eastern university, and this was his first visit to Europe. He was seventeen, a year older than Daney, and he had met both her and her father on several occasions previously when they had visited the States as his parents’ guests. He liked Daney, but she frightened him a little. His great interest lay in science, particularly in astrophysics, and so far he hadn’t got around to learning much about art, whereas with Daney the shoe was on the other foot. Her whole life had been spent amid art and artists and, as far as astrophysics were concerned, she wouldn’t know a parsec from a parallax.

The three of them had spent a couple of days in London, to give Steve a chance to see the Tower, Westminster and Buckingham Palace, and then they had driven back to that remote part of the Norfolk coast where Salgado had his house and studio. Naturally, Daney told Steve about the strange flashes and he was interested.

“Silver flashes that dart here and there over a wide area?” he said. “Why, something of the sort was reported more than a year ago over the Pacific, about a hundred miles out from San Francisco. I remember reading about it in The Astrophysicist and, gee, won’t I be mad if you’ve seen all we’re going to see of those flashes!”

However, luck was with him and, during his first afternoon on the beach, the flashes had put in an appearance. They were still a good way off — too far for Steve even to consider trying to photograph them — but the performance had gone on for a long time. There was also a definite pattern in the flashes’ movements, almost as if they were under the control of a human intelligence, and Steve had taken extensive notes, with the idea of writing an article about them for The Astrophysicist. Then had come the three days during which the flashes were absent.

* * * *

Daney helped the housekeeper get tea ready and she had just brought the teapot to the table when Steve emerged from the darkroom. He was looking rather gloomy and, in answer to Daney’s question, told her that he didn’t think he’d got a satisfactory picture. “There’s a sort of oval-shaped blur on one of the negs,” he said, “but I don’t think it’ll tell us much.”

“May I see it?”

“Well, the negs are drying now. Wait till I make prints.”

Throughout tea there was only one subject of conversation, and Steve had his work cut out keeping his host and hostess to the facts. Daney, in particular, was so sure that the flashes were sinister and evil that it was difficult for her to be objective about them even for a moment. “I think that machine, or whatever it was, is planning to do something terrible to us,” she said, at one point.

“We don’t know that,” said Steve, “and we can’t even surmise it. On the other hand, it does seem that the flashes have a special interest in us or at least in that particular stretch of beach. Every time they appear they get closer in.”

“That’s what I’m telling you!” exclaimed Daney. “And the thing can’t get any closer than it got today without actually touching us. I’ll bet its next move will be to grab us and whisk us off to another planet.”

Her father laughed and handed her his cup for more tea. “You’re just trying to frighten yourself, Daney,” he said. “Still, it would make a change, wouldn’t it? And I’d rather like to be the first terrestrial painter to paint the Martian landscape.”

Daney looked up from pouring out tea and shook her head. “I don’t think it would be any fun at all,” she murmured.

“Perhaps not,” agreed Salgado, “but at least we’d find out exactly what Magellan’s Patagonians went through.”

Steve and Daney exchanged puzzled glances, and the painter grinned at their bewilderment. He helped himself to a cherry bun and munched it while waiting for one of the youngsters to ask him what he meant.

“Don’t ask him, Steve,” said Daney. “He’s always doing this, and if you ask him it only encourages him. The thing to do is keep quiet and then he’ll come across with the information of his own accord — he won’t be able to resist it. Besides, who wants to know about Magellan’s Patagonians?”

“I do,” Steve admitted. “Who were they, sir?”

Salgado’s grin became a trifle triumphant. “What, you’ve never heard of —”

Daney interrupted him with a noise that was nearly a snort. “Your tea, Daddy,” she said, handing him his cup. Then, to Steve, “The next line is: ‘Why, I thought everyone had heard of them! I shouldn’t play if I were you.”

“Well, at least I know who Magellan was,” said Steve. “He was the first guy to sail around the world, wasn’t he?”

“That’s correct,” agreed Salgado, “and during the voyage some members of his crew made a lightning raid on the Patagonian coast. They seized two of the natives, a man and a woman, and sailed off with them, and in my opinion there are no more pathetic figures in history than those two Patagonians. Their terror and misery must have been just out of this world. They’d never seen sailing ships or white men before, then suddenly these things descended on them out of the blue and carried them off. It’s impossible to conceive what they must have suffered.”

“What became of them?” asked Daney.

“They died within two or three days. Perhaps for lack of the proper food or perhaps of broken hearts — the record isn’t clear on the point. The idea, of course, was to take them back to the Emperor as souvenirs.”

“Well, I don’t want to be anyone’s souvenir,” said Daney, “so let’s not go to the beach tomorrow. Let’s give it a few days’ rest.”

“I’ve got to finish my picture,” said her father, “but you and Steve needn’t come. Why not take the car and go into Norwich? Or, if you like, you can amuse yourself in the sailing dinghy.”

“Not this baby,” said Steve. “Nothing on earth could keep me off that beach tomorrow. I’ll be there at daybreak with my camera, and I intend to stick there until I get the shot I should have got today. I’ve a hunch we’re on to something big!”

As soon as he had finished tea he excused himself and returned to the darkroom. Salgado lighted a cigarette and leaned his chair away from the table with his hands clasped at the back of his neck. “Steve’s certainly keen,” he murmured, “and I suppose it would just about make his holiday if he could go back to the States with a clear photograph of a flying saucer. Frankly, I don’t know what to make of it all.”

Daney rose and started to clear away the tea-things. “I don’t like it, Daddy,” she said. “This afternoon on the beach I had a terrible sensation of . . . well, of impending doom!”

“So you don’t think you’ll come tomorrow?”

“Oh, I’ll come, but I would like to know just what we’re up against. It’s all so uncanny!”

“It is that, but so far we’ve had no indication of malevolent intentions. Anyway, I think we can take care of ourselves.”

Daney smiled, reassured by her father’s confidence. He was not a man who scared easily, and both his face and figure were expressive of force of character. He had a chest like a barrel and the muscles of a prize fighter and, in spite of his fifty-five years, he could still lift two sixty-pound weights above his head, one in each hand, and chime them. His tanned face was smooth except for deeply etched lines at each side of his mouth and he had inherited the dark, unflinching eyes of his Spanish forebears — his father had been a Spaniard and his mother English. He was almost totally bald and what little hair he had he wore close-cropped, which gave him a forceful, monolithic look. His was almost a severe face until he smiled, and then it was delightful.

The door of the darkroom suddenly swung open, and Steve burst in holding a still-damp print by its corner. “I’m a prize dope!” he informed them. “I had an almost perfect shot of the object, and then I took a shot of you and Daney to finish the film — well, look!”

Peter Salgado looked, and Daney came and looked over his shoulder. What they saw was a photograph of themselves on the beach, and across them hovered the unknown thing like the shadow of doom. Its four slender legs looked like tentacles threatening to crush them, and its body was a dark ovoid with its minor axis almost as large as its major . . .

CHAPTER II

It was still dark when the alarm woke Steve the next morning and he tumbled out of bed in no very good humor. He did not approve of early rising, and when he went to the window and looked out he was relieved to discover that the morning was foggy. Well, that let him out, he reflected, and he might as well go back to bed. There was no point in taking a camera down to the beach if he couldn’t see a yard in front of him.

So he got back into bed and he was just about to switch out the light when there came a gentle tap on the door. He pressed his face deeper into the pillow and wished he’d never thought about getting up early.

The door opened and he heard Daney address him. “Steve, get up!” she whispered. “The alarm went off minutes ago.”

He opened an eye and scowled. Daney was wearing a dressing gown over her pajamas and she rattled the doorknob urgently. “I’m going to come with you,” she told him, “so up you get!”

“Did get up,” he grunted. “Fog. Can’t take photos in fog. Common knowledge.”

Daney came to the bed and shook him. “But the fog will clear as soon as the sun rises,” she told him. “It always does. Steve, it’s going to be a lovely day!”

Steve opened both eyes. “No kidding?”

“Cross my heart and hope to die. It’ll be a scorcher.”

“Okay.” He heaved himself over onto his back. “I’ll get up, but if the fog doesn’t clear you’ll never hear the last of it —”

“It’ll clear all right, and you can be first in the bathroom. I’ll start cooking some breakfast.”

They couldn’t know it then, but a time would come when they would cherish every detail of that morning. Circumstances lay ahead that would engrave every incident indelibly in their memories, much as people can remember exactly how they spent the day that brought the news of Pearl Harbor. For instance, Daney dropped the frying pan and the clatter it made brought Salgado down to the kitchen like an avenging god in yellow pajamas. He stood in the doorway and glowered. He announced that he was a tolerant man, but that he did feel it was a little early for pandemonium. “Alarm clocks ringing, baths running, armies galloping up and down stairs and then, to crown it all, a noise suggestive of a cosmic collision. What on earth was it?”

“Me dropping the frying pan,” said Daney. “But never mind — have some coffee.”

“What, to keep me awake, I suppose?” he muttered, but his irony was lost on Daney. She poured out a cup of coffee, put it on the table and told him to sit down.

“Drink that, and you’ll feel better,” she said. “I’m going down to the beach with Steve to photograph the flashes.”

“So that’s what it’s all about,” said Salgado, sitting down. “I’d forgotten.”

“I’ve decided not to be frightened of them any more. And the thing that makes them — well, it hasn’t hurt us yet, has it, and it could have if it wanted to. It’s had plenty of opportunity.”

“I guess it’s some natural phenomenon that merely has to be investigated to be understood,” said Steve. “The trouble with all the people who have so far claimed to see flying saucers is that they’ve lacked the scientific approach.”

Salgado drank his coffee and stretched elaborately. “Well, now that I’m awake, I might as well come, too,” he said, “and that being so, I’ll have some breakfast.”

It was daylight by the time they left the house, but the mist had not lifted. It hung over the sand dunes like a cold white veil, and from the direction of the sea the foghorns moaned monotonously. Salgado carried his easel and the canvas he was currently working on, and Steve, besides his camera, carried a picnic basket that Daney had packed before they set out. They had decided to spend the whole day on the beach in the hope of solving the mystery of the flying eggonce and for all.

Slowly the mist thinned and by the time they reached their destination the sun was shining through it like a blurred disk of pale orange light. The sea was mirror smooth and Steve suggested a swim. “It’ll fill in the time till the fog lifts,” he said.

Daney agreed and went off to the dunes to undress.

“We hardly ever come here in the mornings,” Salgado remarked, as he took off his shirt. “So it could be that the flashes are strictly an afternoon phenomena.”

“Maybe,” said Steve, “but somehow I’ve a hunch that we’re the attraction. If we show up, they do. Or at least it’s probably just you and Daney, since you’d both seen them before I arrived.”

Salgado laughed. “That’s a very strange idea. What on earth have Daney and I done that would warrant the attentions of a flying egg?”

“I don’t know, but yesterday there was no mistaking its interest in us, was there? It danced around exactly as if it were viewing us from all angles.”

Just then Daney shouted that she was ready and came running down the beach in her scarlet swimming suit. “Race you to the sandbank,” she cried as she passed them, and Steve, accepting the challenge, ran down to the sea in her wake.

Salgado followed more slowly, and both the youngsters were in the water and swimming strongly by the time he reached the water’s edge. It was low tide and the sandbank that Daney had mentioned was visible about a hundred yards offshore as a long pale ridge of sand against which the seaward waves broke lazily.

The heat of the sun was making itself felt now and the sky, veiled only by the mist’s last vestiges, was a chalky blue.

Daney won the race to the sandbank, and before Salgado was halfway there the youngsters were playing around on its ridged surface, turning cart wheels and doing handsprings. They were both nearly as brown as South Sea Islanders, and Salgado found their vigor and vitality charming. He sketched them in his mind’s eye, and decided that Steve and Daney on the sandbank would be the subject of his next painting. No doubt the art critics would say he was becoming sentimental in his old age, but that was nothing to what they’d said about him in his cubist period.

“Leapfrog, Daddy?” Daney shouted, as he waded up onto the bank.

“All right.”

So the three of them leapfrogged the whole length of the bank and made their final leaps back into the sea at the far end. Daney was first into the water and then it was Steve’s turn to leap over Salgado, who stood waiting for him in the surf with his head down and his hands on his knees.

Steve came splashing through the surf, then, in the middle of his leap, he seemed to waver as if his attention had been distracted. Salgado lost his balance and the two of them tumbled over into the shallow water in a tangle of legs and arms.

Salgado was on his feet first, laughing and panting. “What happened?” he asked, as he helped Steve up.

Steve spat out a mouthful of sand and pointed upward. “The flashes!” he gasped.

There they were — long streaks of silver light that splintered the sky far out over the sea, and the speed with which they moved would have left forked lightning standing still.

Daney had seen them. She struck out for the beach, and the other two made for deep water and followed her. Twice Steve glanced back over his shoulder and caught further glimpses of the flashes. They were getting nearer, darting to and fro in decreasing arcs, and, as he scrambled up the beach, he saw them resolve themselves into a single ovoid of shimmering light.

He ran for his camera with Daney at his side, and he had just grabbed it when Salgado shouted something.

“. . . opened . . .” was the only word that Steve caught, but when he looked up he understood. A sort of hatch had opened in the strange object’s underside and now, as it hovered above the foreshore, they could see into its dark interior.

Steve adjusted the camera with trembling fingers and Salgado joined them. “Wait for it, Steve,” he murmured. “It’s still coming toward us.”

“Sure, but it may dart away again.”

He put his eye to the view finder and waited with his breath held until the machine was almost directly above them.

The camera clicked and at the same moment Daney gasped. “Look out! It’s coming down. . . .”

“Run!” shouted Salgado, and as the three of them turned to run up the beach something came whistling down from the machine — something that coiled about them invisibly.

Invisible tentacles — there was no other way to describe the phenomenon. It was an invisible force that looped round them like a lariat and then pulled tight. They fought against it, shouting at the tops of their voices, but it was useless. Inexorably the unseen tentacles fastened about their arms, their legs and their bodies, and in the next second they were being dragged off their feet.

Daney, sandwiched between Steve and her father, looked up and saw that the machine was hardly twenty feet above them. There was no sign of a pilot. A low-pitched whirring issued from the machine and that was all. The whole experience was almost too dreamlike even to be frightening . . .