3,65 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Thunderchild Publishing

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Antigeos

- Sprache: Englisch

The Cox brothers, who live on a Kentish marsh, pick up Morse messages from Professor Pollenport who had left the Earth five years earlier and is having a spaceship built on Antigeos so that he may return to England. The Professor's expedition had been backed by Lord Sanderlake's Daily Messenger, whose science editor he had been. Rigby and Bryan Cox rush to tell Sanderlake that they have picked up Pollenport but need a powerful transmitter to be able to reply to him, through space, to Antigeos. Sanderlake agrees, hoping to get an exclusive newspaper scoop, but the secret is not kept and unscrupulous financiers begin to gamble on the chance of exploiting planets, as in the past they connived to exploit colonies.

What happens to Professor Pollenport and his spaceship, to the Cox brothers, and. to all the other people who become involved in the story, makes this new Antigeon adventure enthralling, highly original, and as wittily told as its predecessors.

Paul Capon (1912-1969) was a British novelist of considerable reputation. He had over twenty novels to his credit and counted film editing and script writing as part of his experience. He traveled extensively in Europe and made hobbies of chess, book-collecting and swimming.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 278

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

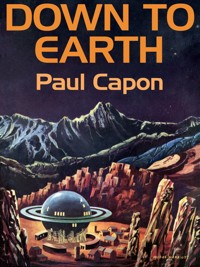

DOWN TO EARTH

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

DOWN TO EARTH

Paul Capon

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed inthis novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

DOWN TO EARTH

Copyright © 1954 by Paul Capon

Published by arrangement with the Paul Capon literary estate.

All rights reserved.

Edited by Dan Thompson

A Thunderchild eBook

Published by Thunderchild Publishing

First Thunderchild eBook Edition: April 2015

Cover illustration by Mudge Marriott

CHAPTER I

I

A cold wind was streaming across Pengeness Head and a cold grey sea was breaking on its eastern shore, throwing up more shingle on to the vast shingle-banks for which the peninsula is remarkable. The wind rattled the doors and windows of the huts that huddled round the lighthouse, and rippled the stretches of dead water out on the marsh where the water-birds stood with their backs to it, like old men with hunched shoulders and their hands in their pockets. And further inland the wind swept over the abandoned rifle-ranges and wailed into the streets of the peninsula’s one town, Brydd, so that it was small wonder there was nobody about that afternoon.

Digby Cox, coasting down Beacon Hill in his ancient station-wagon, surveyed the town from afar and shuddered. “My home-town,” he muttered, “and how I hate it. Who could be a success in Brydd?”

Once Brydd had stood as an outpost against possible invasion, but, since the invention of aircraft, those days were past, and now there was little reason for its continued existence. It was on the road to nowhere and it was the centre of nothing. Its monastery had been a ruin for four hundred years, its barracks for forty, and yet three thousand people lingered on, taking in each other’s washing and braving the winds that swept in from all four quarters.

Digby came to the foot of the hill and accelerated angrily. “Bankrupt,” he exclaimed, with a certain relish. “That’s the long and the short of it, we’re bankrupt. Ruined by big ideas and small means!”

The station-wagon rattled over the disused railway’s level-crossing, and then Brydd’s huge and ugly church loomed into view. Digby skirted it, came out into the Square and pulled up in front of the shop that had been his father’s, and was now his and his brother’s. It was a fine, double-fronted shop — shuttered today, for early-closing — and its stock mainly consisted of wireless-sets, television-sets and all the accessories that the modern world is heir to. There was even a tape-recorder and, as Digby let himself into the shop, his eye fell on it, and he gave a short laugh. “I must have been crazy when I ordered that,” he reflected. “Who on earth in Brydd would want a tape-recorder, even in this year of grace nineteen seventy-three?”

He closed the door hurriedly because of the wind, but some of it was too quick for him and a number of leaflets lying on the counter went leaping into the air and scattered themselves on the floor. He cursed sombrely and went through into the back of the shop.

There was no sign of his brother either in their living-room or in the kitchen, so he had to brave the wind again, crossing the garden towards the large shed at the garden’s end that served them as a workshop. Strange-looking aerials festooned the shed, which was a wooden one, and it had been built at that inconvenient distance from the house on the insistence of the insurance company. “One spot of lightning,” the agent had said, “and up the whole show will go in smoke! To say nothing of the outlandish voltages you’ll be using.”

Digby pushed open the door and went in. “Hullo, Bryan,” he said, but his brother, at the far end of the shed, had ear-phones on and did not hear him. In any case, he had quite extraordinary powers of concentration.

An electric kettle had just come to the boil on the bench nearest the door, and Digby went to it. He spooned some tea into the tea-pot and poured in the boiling water.

“Hey, Bryan,” he shouted. “I’m back and I’ve made tea!”

Bryan jerked off the ear-phones and swung round. “A most extraordinary thing!” he exclaimed. “I’ve been analysing sun-spots on a ten-M wave-length, and now I seem to be picking up Morse!”

Digby strode the length of the shed and studied the instrument-panel. “Nonsense,” he said. “You can’t be picking up Morse on that fixing. Either your screening is faulty or you’re cuckoo — and my preference is for the latter explanation.”

“No, seriously,” said Bryan, holding up the earphones. “You listen.”

“No, thanks. Those things give me a headache, and I’ve enough on my plate without that.”

“But you can read Morse, and I can’t! Come on, Digby — I’ll hook up the amplifier!”

“Even that doesn’t tempt me,” said Digby, shaking his head. “I suppose I’m just not in the mood for cosmic Morse. Come and have a cup of tea, and I’ll tell you my news, which is lousy.”

Bryan reluctantly climbed down from his stool and followed his brother to the bench where the tea-pot stood. “You mean we’re out of business?” he asked.

“As good as. My efforts to negotiate an overdraft were turned aside with a light laugh, so then there was nothing for it except to go to Cunningham and tell him we couldn’t meet his account. I asked him for another six months’ credit, but if he heard me, he didn’t let on. In fact, all he could say was, ‘Well, Mr. Cox, I’m prepared to help you to the extent of taking back everything that’s unsold — ’ ”

Bryan interrupted his brother with a gasp. “All this?” he asked, with a gesture towards the equipment with which the shed was filled.

“Most of it. And half the stock in the shop. Actually, there is just a faint chance that we can pull through, but to do so we shall have to give up all dreams of fame and glory. No more experiments in radaroscopy, no more research into the nature of cosmic rays, and no more fun and games with the universe as our playground. Instead, we shall just have to devote ourselves to repairing radios, selling light-bulbs and installing door-bells, which will be a change, to say least of it.”

He poured out two cups of tea, and for some minutes nothing broke the silence except the whine and throb of the generating-plant in the adjoining out-house. Bryan’s expression suggested that his heart would break and all Digby’s sympathy went out to him. At eighteen, he reflected, one has met with fewer disappointments than at twenty-five, and they are proportionately harder to take. Also, Bryan was the more single-minded of the two and exploring cosmic space by means of radar-techniques was his ruling passion.

“When’s Cunningham sending for the stuff?” he asked, at length.

“He mentioned Friday.”

“The day after tomorrow? . . . Oh, God!”

He drank his tea and returned to the bench where he had been working.”

“Digby, I wish you’d listen to this Morse,” he murmured. “It’s most peculiar.”

As he spoke, he inserted the jack-plug of the amplifier and pressed a couple of switches. The amplifier hissed and crackled and then, underlying the atmospherics, came the unmistakable stutter of Morse.

“There you are, Digby!” he shouted. “What’s that? Morse or Scotch mist?”

Digby joined him and stood for a few moments listening. “Yes, it’s Morse, all right,” he agreed presently, “but it’s as I said. Your screening’s faulty and you’re picking up Morse on another —”

He broke off and the degree of interest in his expression increased. He put his head nearer the amplifier and Bryan asked what had struck him.

Digby made an impatient gesture, then exclaimed, “Good God! . . . Bryan, where’s a piece of paper?”

His excitement was infectious, and Bryan hurriedly thrust a note-pad and pencil in his hand. Digby scribbled rapidly and too illegibly for Bryan to be able to make out the message, but under his breath he suddenly muttered, “My God — Pollenport!”

The name burst across Bryan’s consciousness like a star-shell, and he gazed up into his brother’s face in wild surmise. Was he really getting a message from Jonah Pollenport, the man who, five years before, had commanded the first spaceship ever to leave the earth?

As long as Digby scribbled there was nothing for Bryan to do except curb his impatience, and half a millennium seemed to creep by before at last his brother said, “All right, Bryan. You can switch off.”

“But the Morse is still coming through!”

“Yes, I know, but it’s simply the same message repeating itself on an endless band,” said Digby, then added, with maddening calm, “As a matter of fact, it’s from Jonah Pollenport, and he’s on the planet Antigeos.”

“Well, for God’s sake tell me what the message is before I burst!” cried Bryan, switching off.

Digby consulted his note, and read, “This is Jonah Pollenport calling the Earth from the planet Antigeos. Will anyone receiving this signal please acknowledge on the same wave-length. The signal will now be repeated. . . .’ ”

“Antigeos?” whispered Bryan. “Then it does exist after all?”

“Presumably,” said the calmer Digby. “Unless — unless we’re the victims of a hoax.”

Bryan hardly heard him. He was gazing at the silent amplifier rather as Sir Galahad must have gazed at the Holy Grail and, when he found his voice, he asked what were the chances of anyone else picking up the signal.

“Small,” Digby assured him. “We haven’t a monopoly of the ultra-short waves, but we do know that there isn’t a great deal of research being done in that field. Of course, Pollenport may be using a variety of wavelengths, but, even if he is, he’s limited to the ultra-short ones by the Heaviside — Kennelly layer.”

“Naturally,” said Bryan. “So now we just build an enormously powerful transmitter and make contact with him?”

“Oh yes? And how can we build an enormously powerful transmitter between now and Friday? And, without cash or credit, where are we going to get the necessary equipment for stepping up our voltages from?”

“From Cunningham!” cried Bryan. “Yes, we’ll have to let him into the secret. It’s horrible having to share the glory with him, but there’s nothing else for it.”

Digby laughed. “You’re quite an optimist, aren’t you?” he murmured. “Brother, you can take it from me that Mr. Cunningham isn’t interested in glory. He wouldn’t see any percentage in it, and the knowledge that we’ve picked up a message from Pollenport would leave him as cold as an iceberg. No, we’ve got to think of something else.”

He strolled pensively back to the tea-pot and poured himself out another cup of tea. He lit a cigarette with shaking hands and Bryan switched on the amplifier once more. The Morse was still stuttering faintly behind the atmospherics and Bryan’s sense of frustration became almost impossible to bear. “Think of it, Digby!” he murmured. “You and I are the first men on Earth to get proof of the existence of Antigeos!”

Digby didn’t reply, and Bryan struggled to recall all that he’d ever heard about Antigeos. To the best of his knowledge the planet’s existence had originally been hypothesised by a Professor Wittenhagen as early as the nineteen-forties, but it wasn’t until nearly twenty years later that Wittenhagen’s theory had been published. According to the theory, Antigeos constituted the Solar System’s tenth planet, and that it had escaped the astronomers’ notice for so long was accounted for by the fact that it shared the Earth’s orbit, revolving round the sun at the same speed as the Earth and at a point diametrically opposite to it, so that, from the terrestrial point of view, it was forever hidden by the glare of the sun itself.

As regards details of the Pollenport Expedition, Bryan was hazy He had been only thirteen at the time, and he was about to question his brother when Digby suddenly spoke.

“I’ve got it!” he exclaimed. “Lord Sanderlake!”

“Sanderlake?” echoed Bryan. “But why him in particular?”

In fact, he found Digby’s suggestion puzzling. He only knew Lord Sanderlake as the proprietor of the Daily Messenger, and he instinctively felt that it wouldbe a mistake to hand over their secret to the popular Press. If they did that, the whole thing would probably be taken out of their hands and all they’d get out of it was a miserable cheque for a hundred or so.

“Well, I suggest Sanderlake,” said Digby, “because he was the original instigator of the Pollenport Expedition. Didn’t you know that?”

Bryan shook his head. “No, I didn’t. Tell me about it.

“Well, Jonah Pollenport, you know, was the Daily Messenger science editor, and I forget just how it was that he got hold of the Antigeos theory, but anyway he did get hold of it and then Sanderlake took it up in a big way. He financed the building of the spaceship, and the idea was that Pollenport should circumastrogate the orbit to find out whether or not Antigeos existed. There were any number of snags and hitches, but in due course the spaceship did take off — and has never been heard of since!”

“And it was never intended that he should land on Antigeos?” Brian put in.

“Definitely not, because of the difficulty of taking off again. No, I can only suppose that Pollenport is on Antigeos because he crashed on it, and presumably he and his companions have spent the last five years in building a transmitter out of parts of the wrecked spaceship.”

“Who were his companions?”

“Let me see — I think he took about four people with him. A chap called Sam Spencross was one and he was an expert on reaction-propulsion. And then there was Pollenport’s assistant, whose name I forget — I think he was a negro, and another young man who bought his passage by winning a football pool.”

“Oh yes, I remember,” said Bryan. “I remember that at school we were all sick with envy of him. Wasn’t his name Timothy something? Fox, or Fry? Anyway, a Quaker name.”

“Penn,” said Digby. “Yes, that’s it — Timothy Penn. And I think that’s about the lot, but it was strongly rumoured at the time that Pollenport’s daughter had managed to get on board as a stowaway. The rumour was never confirmed, but she certainly disappeared at about that time.”

“And now you think we ought to get in touch with Sanderlake?” murmured Bryan. “But if we do that, won’t he just pinch our secret and then tell us to get lost?”

“No, I don’t think that that would be quite Sanderlake’s style,” said Digby. “He’s a bit of a crook, of course, but not a petty one, and in any case there’s no need for us to tell him the wave-length. Come on, let’s go and telephone him!”

II

Lord Sanderlake was rather frightened of storms, except for those of his own making, and as he listened to the wind howling around the turrets of Narraway Towers he bitterly regretted his decision to winter in England. Squall upon squall of rain rattled among the trees outside and he visibly shuddered, cowering deeper into his armchair and biting his finger-nails nervously. In fact, he was an excessively timid man and the struggle he put up against his timidity had been the main-spring of his whole enormously successful career. He ranted and blustered, pretended to be Napoleon and got his own way, but underneath it all he was still little Jim Cooper, who was afraid of storms, pussy-cats, the dark and his own shadow.

The red telephone at his side buzzed discreetly and, reaching for it, he grunted into the mouthpiece.

A woman’s voice answered him. “Lord Sanderlake?”

He recognised the voice as that of his senior secretary and grunted again. She was speaking from the Daily Messenger offices, to which the telephone was connected by private line, and Lord Sanderlake heard her say something about a young man who wanted to speak to him.

“Can’t hear a thing,” he snapped. “Speak up, Dora — there’s a storm here making more noise than the wrath of God. A terrible storm!”

So Dora spoke up and told him she had a young man called Digby Cox on the line. “He’s speaking from Brydd,” she said, “and he refuses to talk to anyone except you. He’s a very insistent young man and he assures me he’s on to the greatest news-story since — since —” She broke off and tittered, causing Lord Sanderlake to writhe with fury.

“Don’t titter, Dora,” he roared. “Since what?”

“Well, since James Watt invented the steam-engine,” she told him. “I informed Mr. Cox you were down in the country and he asked for your number. Am I to give it to him?”

“Yes,” said Lord Sanderlake, and hung up. He had once missed a scoop through refusing to take a telephone-call, and he had no intention of allowing it to happen again.

A sudden appalling crash brought him out of his chair with a jerk and he gazed fearfully towards the windows. Then he touched the bell and, going to the tantalus, poured himself out a stiff whisky.

The butler came in as he was drinking the whisky and, in the nick of time, Lord Sanderlake assumed one of his several great-man poses. “Oh, Davidson,” he said, “I think a chimney-pot or something’s been blown down. Go and investigate, will you?”

Davidson was a bulky, saturnine man, youngish for a butler, and his dark eyes, as he gazed at his master, were inimical.

“Certainly, my lord. I’ll send —”

“You’ll send no one!” exclaimed Lord Sanderlake, practically shouting because he was also afraid of butlers. “You’ll go yourself, and find out exactly what’s happened. Good God, man, you’re not scared of a little wind, are you?”

“No, my lord; but I must respectfully point out that it is not my place —”

“Your place!” snorted Lord Sanderlake. “Your place is to do what I tell you and like it! You’ve been reading too much Compton-Burnett, that’s your trouble.”

“I do read Miss Compton-Burnett,” admitted the butler, conversationally, “but I trust I am not so protean as to allow myself to be influenced by that lady’s works, admirable though they are. No, my lord, it’s simply a matter of —”

He was interrupted by the telephone ringing — the black one this time — and Lord Sanderlake grabbed it. “For God’s sake, Davidson,” he muttered, with his hand over the receiver, “find out about that chimney-pot and don’t talk so much. . . . Hullo?”

His caller announced himself as Digby Cox and lost no time in stating his business. “Well, Lord Sanderlake, my brother and I have some very important news for you,” he said, “and we’re wondering if we could come and see you.”

“News? What news?”

“I’d prefer to let it wait till we meet.”

“No, no, no. I can’t hold myself at the mercy of every crank and crackpot in —”

“All right, Lord Sanderlake. We simply thought you’d be interested, that’s all. Particularly since we’re on to the biggest news-break since —”

“I know. Since Watt invented the steam-engine.”

“Well, actually I was going to say since Columbus reported back from America.”

“Oh, so you’ve raised the ante, have you? But surely, young man, you can give me an inkling, just a hint as to what it’s all about?”

There was a long pause, then Digby Cox said: “It’s about Jonah Pollenport. You see, we’ve had a message from him.”

Lord Sanderlake gasped. “What’s that? From Jonah Pollenport? Then where the hell is he?”

“May we come and see you?”

“What? Yes, of course.” Lord Sanderlake was almost stammering in his excitement. “You’re at Brydd, aren’t you? Well, I’ll send a car for you.”

“We’ve got a car, thank you,” said Digby, “and we’ll be with you within the hour.”

Lord Sanderlake’s hand was shaking so badly that he could hardly replace the receiver on the cradle. “Jonah Pollenport!” he muttered, and finished his whisky. “Why, if that young man’s speaking the truth Watt and Columbus just aren’t in the running! If that doesn’t lift us to the ten-million mark, nothing will.”

He forgot all about the storm and, dropping into an armchair, sat gazing into a future that shimmered with golden promise. For five years he had been guiltily conscious of mishandling the Pollenport business, and now it looked as if he might be given a chance to redeem himself. Or was someone trying to take him for a ride?

His thoughts were interrupted by Davidson returning and announcing that it wasn’t a chimney-pot after all “It was an elm, my lord,” he said. “Or, rather, the branch of an elm.”

Lord Sanderlake’s nervousness revived and he moistened his lips. “Yes? What happened?”

“The branch came down on the small conservatory, virtually demolishing it,” said Davidson. “To be frank, my lord, I have often questioned the advisability of allowing such treacherous trees to flourish in the vicinity of the house. As your lordship no doubt knows, every elm is familiarly said to get its man.”

Lord Sanderlake winced, and his heart gave an uncomfortable jump. “How many elms are there near the house?” he asked, hoarsely.

“Five, my lord, not including the small wych-elm by the east wing, which can hardly constitute a danger.”

“Five, eh? Then see to it that every one of them is felled. Tomorrow.”

“Very well, my lord,” said Davidson, grinning and drunk with power. “And what are your lordship’s wishes regarding the timber?”

“The timber?” mumbled Lord Sanderlake, looking vague.

“It won’t be without a certain value,” Davidson assured him, “particularly in an agricultural district such as this. As your lordship is no doubt aware, no other wood is suitable for making the hubs of wagon-wheels and, in fact, I believe the rule is elm for the hubs, oak for the spokes and ash for the felloes —”

Lord Sanderlake suddenly lowed like a menaced bull and sank back into his chair. “Davidson —” he began, then broke off with the realisation that no words could adequately express his exasperation. He often asked himself why he kept the fellow, but the question was always a rhetorical one. The truth was that Davidson knew too much to be lightly dismissed. In fact, Lord Sanderlake sometimes suspected that he knew everything.

“Yes, my lord?”

“Nothing,” said Lord Sanderlake. “Except that a Mr. Digby Cox and his brother will be calling shortly and you can show them up as soon as they arrive. However, don’t leave me alone with them until I give you the word. That’s all.”

As soon as the newspaper-baron was alone, his thoughts returned to his erstwhile science editor. “A message from Pollenport?” he murmured, but what exactly did that portend? Did it mean that Pollenport was back on Earth? Or was he on that hypothetical planet Antigeos? Or was he in space?

Lord Sanderlake’s gaze went to the red telephone and for some moments he played with the idea of ringing the office and telling them to stand by for drastic action. He had a predilection for impinging himself upon the workings of his newspaper with dramatic suddenness; and to scream at his harassed chief editor “Kill the front page!” was his idea of good fun, but sober reflection told him that in this case he would hardly be justified. It was still barely six o’clock and even if the news-break did prove as sensational as Digby Cox claimed there would still be plenty of time to reorganise the paper’s make-up, and if there was one thing that Lord Sanderlake liked better than screaming “Kill the front page!” at six o’clock, it was screaming “Kill the front page!” at eight o’clock. Besides, for all he knew, the Cox brothers might never turn up. They might be simply pranksters. Or lunatics.

However, the Coxes did turn up, and as Davidson showed them into the room Lord Sanderlake was relieved to notice that neither bore any visible signs of mental derangement. Digby in particular had a serious and sensible face, and there was a sobriety about his bearing and clothes that the newspaper-proprietor found infinitely reassuring. The younger brother, it was true, was untidier and more rugged-looking, but, after a moment’s scrutiny, Lord Sanderlake decided that he too was all right, and so dismissed Davidson with a nod.

The suspense was becoming unendurable and it was that that decided him not to offer the Coxes a drink. He felt that there wasn’t a moment to waste and, as soon as the three of them were seated, he brought up the matter of Pollenport. “Where the devil is he?” he asked.

“On Antigeos,” said Digby.

Lord Sanderlake looked incredulous. “Yet you’ve had a message from him, you say?”

“Yes. You see, my brother and I own a small electrical engineering business at Brydd,” he said, “but our real interests lie somewhat further afield. To be perfectly frank, we’ve practically bankrupted ourselves in astronomical research.”

“What, telescopes and so on?”

“Not exactly, but, Lord Sanderlake, do you know anything of blind astronomy?”

“What, radaroscopy? Well, I know the principle of it; and that’s what you’ve been indulging yourselves in, is it?”

“Yes, and just lately we’ve been doing some special research on sun-spot activity, using a particularly sensitive receiver. And this afternoon my brother found himself picking up Morse on a wave-length where no Morse could be.”

Lord Sanderlake glanced from Digby to Bryan, and back again. “From Pollenport?” he whispered.

“Yes,” said Digby and, as he spoke, he drew an envelope from his pocket. It was a short length of recording tape together with the text of Pollenport’s message.

“Have you a tape-recorder here?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Lord Sanderlake, with a glance towards his desk. “That’s a recording of the message, is it?”

“It is. Of course, it doesn’t prove anything, because we could easily have faked it, but we thought you might like to hear it.”

“Certainly I should,” said Lord Sanderlake, and took the tape. He went across to his desk and opened a deep drawer in which was a tape-recorder.

Davidson came in, ostensibly to make up the fire, just as the stutter of Pollenport’s Morse started to emerge from the drawer and Lord Sanderlake stopped the machine. “Know anything about Morse, Davidson?” he asked.

The butler bowed assent. “I must admit to a certain familiarity with it, my lord,” he murmured. “When I was hall-boy in His Grace’s service I was enrolled as a scout in the troop attached to the estate. In fact, I rose to be the patrol-leader of the Buffaloes, and among my proficiency-badges I numbered one for Morse.”

“H’mph. Well, see what you can make of this.”

He switched on the machine again and Davidson listened attentively. As the import of the message dawned on him, he glanced at the Coxes and smiled superciliously.

“Well?” muttered Lord. Sanderlake, as the tape came to an end.

“It’s a message from Professor Pollenport on the planet Antigeos, my lord,” said Davidson. “Or, at least, that’s what it purports to be. It merely requests anyone receiving the message to acknowledge it on the same wave-length.” He gazed into space for a moment, then added unexpectedly, “Yes, of course — it was your lordship who instigated the Pollenport Expedition, wasn’t it?”

“That’s right, Davidson. But for me there wouldn’t have been any expedition.”

Davidson returned to the fire, but went on talking. “I’ve always considered it a pity that the enterprise was taken over by commercial interests in its later stages,” he murmured. “In fact, they even sent a representative to accompany the expedition, did they not? A military gentleman. A Major — no, I’m afraid the name escapes me for the moment.”

Lord Sanderlake glanced up from the text of Pollenport’s message. “That’s enough, Davidson. Do whatever you have to do, and leave us.”

Davidson swept the hearth meticulously, then retreated. However, it was seldom that he did not permit himself the last word, and now, as he closed the door, he murmured: “Ah, the name’s returned to me now, my lord. It was, of course, Major Stewart McQuoid!”

Lord Sanderlake frowned irritably, and handed the message back to Digby. “Could it be a hoax?” he asked.

“Unlikely,” said Digby, and gave his reasons.

“Yet you made no attempt to reply?”

“We couldn’t,” Digby told him. “We’ve no transmitter nearly powerful enough, nor any means of building one. As I’ve already mentioned, we’re broke and our credit is exhausted.”

Lord Sanderlake jumped up and started pacing the room. Outside, the wind howled and blustered, but now all his fears were forgotten. He saw himself as having the century’s greatest news-story within his grasp and his sole thought was how best to handle it.

“You’ve told no one else?” he asked.

“No one.”

“Then what are the chances of this message being picked up by some other chap?”

“Small,” said Digby. “In fact, I should say that they’re about a million to one against.”

“Good.” Lord Sanderlake returned to his chair. “Now I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We three are the only people in the world who know about this, so we’ll just keep our mouths shut and go to work. How much do you owe?”

“Between three and four hundred.”

“Then have the bills sent to me, and order all the equipment you want. And how long will it take you to build this transmitter?”

Digby and Bryan exchanged glances. “A fortnight,” said Bryan. “If we work at it day and night.”

Digby smiled. “I think that’s a little optimistic,” he murmured, “but shall we say three weeks?”

“Right!” said Lord Sanderlake. “And now we come to the question of your remuneration and I’ll tell you what I’ll do. If you succeed in communicating with Pollenport within three weeks I’ll pay you —” he hesitated, biting his thumb-nail —”I’ll pay you two thousand pounds! How’s that?”

“Excellent,” said Digby, and they shook on it.

Then Lord Sanderlake touched the bell, and when Davidson opened the door, everything seemed to happen at once. A window burst open and a gale of wind came streaming in, lifting the curtain and filling the room with its force. For a moment Lord Sanderlake stood as if transfixed, then his mouth dropped open and he slid to the floor with a crash.

“Ah, swooned,” remarked Davidson, and went to him. He loosened Lord Sanderlake’s collar and somewhat roughly pushed his head down between his knees.

“Shall I pour out some whisky?” asked Digby.

“Hardly necessary, I think, sir,” said Davidson. “He’s hyperthyroid, you know, and certain things upset him. Cats, for instance, and —” he glanced towards the window which Bryan was struggling to close —”and storms. Nervous, in fact, like all these new creations.”

CHAPTER II

I

The view from the hillside window was dazzling in its splendour. Timothy Penn, sitting in the silent room for a tenth part of each Antigean day, never tired of its beauty. The Earth could offer nothing comparable, and the Antigean word for that part of the northern continent could be translated roughly as ‘the Land of Fountains’ or ‘the Land of Many Waters’.

It was on the sea-coast to the east of the great desert and for centuries it had been preserved as a beauty spot on account of its hundreds of geysers and natural fountains. From his window Timothy had a perfect view of the whole valley, which was divided into two by a river as broad as the Thames at Tilbury. The grass of the valley was greener than any he remembered ever seeing on the Earth, just as the waters of the river were clearer, but for all that he was homesick, almost despairingly so. He gazed past the sparkling forest of fountains towards the sun and, squinting at it, dreamt of his native planet, much as five years before he had dreamt of Antigeos while idling in Hyde Park and blinking into the sun’s glare.

He grinned a little ruefully at the recollection, but told himself stoutly that even if he had known all that was in store for him, he would still have come — yes, even if the worst came to the worst and he had to spend the rest of his life in an alien world. It had been an enchanted adventure and, in any case, if he had not embarked upon it, he would never have met and married Rose Pollenport. He felt that almost any fate would be bearable as long as he had Rose.