4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksprint

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

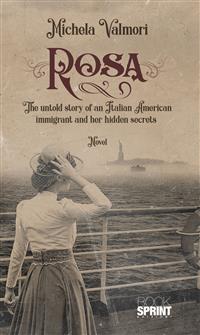

Living as a young Italian American woman in early 1900 New York was not easy; seventeen year-old Rosa, arrived in America from her sunny and dry spot of land in Italy, had to face many life struggles. Her many expectations were soon shattered by reality and despite her determination she had to fight hard in order to conquer her corner of the world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Michela Valmori

ROSA

The untold story of

an Italian American immigrant

and her hidden secrets

Acquista la versione cartacea adesso in 48 ore a casa tua:

Clicca qui

www.booksprintedizioni.it

Copyright © 2018

Michela Valmori

To my brave ancestors,

to my family,

to all my readers,

to the Italian FULBRIGHT Board,

to the University of Notre Dame,

and to the Nanovic Institute.

They all inspired me in different ways

Chapter 1

It was dry back home, when Maria Rosa left the farm and rocky hills behind. It was late spring when she left the burning dirt, and sweltering heat behind her to cross a field of blue; so blue that the sky and sea often merged into one and there was nothing to see for miles. The only break being a plume of smoke spit up by the steamship as it powered through storms that raged like an angry mother and tossed her from side to side. She felt a sense of dread in the pit of her stomach: would she ever see America? The endless blue horizon gave way to a grey line that slowly became the new world that she had dreamed of reaching.

“Anto’, qua… qua!”{1} The man in front of her heaved an enormous case over his shoulder, the air was stifling — sweat, dirt, piss. People were herded onwards. Whistles blew, she couldn’t see from where. These chaotic ructions aggravated her sense of babelism and anxiety to the point where her knees weakened and her mind almost shut down. Mannaggia,{2} she had lost sight of Antonio, yes, she had promised to never lose him — l’aveva giurato.{3} Pushing across the human tide she searched frantically. “Antonio! Antonio! Dove sei andato a finire?”{4}

Emerging into an opening, light from the glass ceiling illuminated Antonio — he wasn’t alone. “Pigghia cura ri idda”{5} said the ill-omened man who held him by his lapel. They looked into her eyes, told her things she couldn’t understand — “Jes, ser”, she repeated like a broken record. There were others in a smaller hall waiting with them and when the guard left for a Lucky Strike the man next to Rosa stood up on his chair, peeking into the opaque glass slab above the door. A spider crawled out from underneath the bench, resting next to her boot. Mid-motion to squash it, Antonio cried — No! Mamma dice chi porta furtuna!{6}

Rosa was seventeen years old, young and beautiful like a blooming rose of May, her skin was bronzed by the first suns of Italy, her lips were red and her hair was black and wavily long. She could speak no English, but she was smart and even though she had been forced to leave school after her second year of elementary instruction she could fare di conto.{7} She administered the family income and she was the one every Valmori came to ask for instructions or relied on when things were complicated. The family had no money — non ci sono le monete, e le donne servono nei campi!{8} — that’s what Giuseppe, her father, kept saying; there was no point for Rosa to go to school as her future would have been that of a wife and a mom, and certainly not that of a teacher, because he knew what Rosa secretly wanted to become, an elementary school teacher — la maestra del paese.{9} Giuseppe would have loved nothing more than the realization of this dream, but he had always been a man who had clung to pragmatism, and daren’t hope for such a brilliant, yet impossible future for Rosa. When Antonio decided to leave for la merica Rosa was just a little girl. Sixteen years old but a clear mind, she was engaged to an older Italian man whose company she didn’t enjoy. She was working as a seamstress for the tailor of her small town and she was helping her family in the fields to grow vegetables, which she ultimately knew was not a future she could countenance. She was acutely aware that she didn’t want to cope with la miseria{10} that was everywhere in post-Garibaldi Italy.

Furthermore, she knew from seeing her mother’s example that she had no intention of spending her life inheriting an insipid existence as a wife whose devotion to her husband and children would inevitably mean abandoning her own identity; after all she was smart, that is at least what il maestro{11} Pasquale used to repeat to her every single day. Rosa’s family led a life made of hard work and no comfort, where sometimes sadness and tragedy had made their appearance. Alas, the modest means that her family had endured for generations remained a daunting obstacle, her family was poor and had been for many generations. No escape from poverty would have ever been possible for such a family; it was for this reason that as soon as she heard Antonio mentioning la merica she didn’t even hesitate. Life had already been pitiless in Italy to her, therefore, she felt she deserved a new possibility.

***

She looked up at the flag swinging lazily above her as she passed inside, glaring bright red and blue in the afternoon sun. Her stomach lurched, with lingering seasickness or apprehension. She could not say which while she was fixing her gaze on the mass of people shuffling slowly forward before her. There were people adorned with coats, hats, and suitcases, despite the summer heat, carrying everything they owned in their two hands, as she was. She shifted her grip on her brother’s hand, her fist slicked with perspiration. “It’s all right”, she told him. His gaze wandered to hers, and she saw her own fear of their unknown future reflected in his face. She tried to smile, to assure him that they would be fine, better than before, this is America. But as he glanced about her and saw children wandering alone in tears, old women coughing violently into their handkerchiefs, young men arguing in Italian with others arguing in English; she found herself unable to offer any assurance. She could only hope she would be right about coming here and leave their poor everything behind. The spider was no longer there but still she told Antonio not to cling too hard to the culture they had just left where no one dares, not even by mistake, to spill oil on the floor or break a mirror, since fortune, in America, was something to be conquered and defended.

It was late when they separated her from her brother and led her into a white room whose walls were made up of small bricks. They asked her to sit and wait for her turn but the bitter cold that pressed against her bones inspired her to go first voluntarily . They spoke no English but then a short man with a strong Neapolitan accent was sent there to act as an interpreter. They asked Rosa a few questions about her identity: her family back home, the money she had; they seemed particularly curious whether she had a man expecting her at Battery Park. It sounded so surreal that also here, in the land of opportunities – where women could do proper jobs and get an education – she still needed to have a man waiting for her as a symbol of her credibility. It was not meant to be like in Italy here — dove l’uomo è uomo{12} — she had just set foot in the land of freedom, welcomed by Lady Liberty and her miraculous torch, yet a man was necessary. “No”, she said. “I am here with my brother Antonio, he is 32 and he will take care of me”, that sounded like the most logical form of compromise she could come up with. Although uttered through reluctant, clenched teeth, it had cost her a fortune to pronounce those words, to give up her honor and pride. The truth was that it was her who would be taking care of him; clean the house, cook the food. This was certainly not her ambition but it was what she had to promise to her parents, Giuseppe and Maria — mi prenderò cura di lui{13} — “I will take care of him”, her last words.

They were not happy when she left but they couldn’t keep her from going, not after what she had seen in Italy.

That’s why in the end they decided to let her leave under one condition, that she would honor her brother, look after him and not work. It was mainly Maria, her mother, who seemed favorable, because she could see no happiness in Rosa’s eyes when she looked at her older fiancé, the son of the doctor in town, almost a doctor himself, who could have given her a wealthy and satisfying life. Even further, Maria felt that her young Rosa could be meant for different things than being just a wife and a momma, or at least she hoped so. Rosa was young and didn’t know what love meant because she had never experienced it, and she also ignored what life was like outside that crowd of shabby houses and green fields of Collina, given she had never stepped over the right bank of the river Ronco. However, she possessed a virtue unknown to many: a strong determination and a robust will. She had seen too much, for her tender age, in that unfair small town where she had been living since her earliest wail and she felt like her moment had come. Sometimes it seemed to her that things hadn’t occurred in vain in the end, but indeed the most tragic event of her life served as a phoenix, where death had allowed the opportunity for re-birth.

It was her determination that made her come up with the right thing to say at the proper time: – ritornerò – “I’ll come back”, that’s what she had said, feeling the harsh guilt for lying to her momma, because she well knew she would never go back to that archaic world. “I will make some good money and I will become a skilled tailor, so that – she knew well what Giuseppe wanted to hear – once back in Italy I will be able to do some sewing work at home and take care of my family”. In fact, Rosa was perfectly aware that it was the last time she would see her momma, touching her maternal skin, maternal skin whose scent painfully reminded her of the comfort she was leaving behind. “Momma I will miss you and I will write you every week” Rosa pronounced as soon as she was secretly assaulted by a lump in her throat. Those words sounded realistic and benevolent, leading Giuseppe, who naturally claimed the last word on the matter, to give her permission to leave on board of the Bulgaria Ship from the port of Genoa, together with Antonio. It was April 18th1907 when Rosa and Antonio bid farewell to their land. Both siblings felt fearful, but for Rosa, the great unknown evoked in her wide-eyed excitement she had never before experienced. In truth Rosa had never doubted her departure and even though she let her papa think his approval was paramount, there was nothing that could have prevented her from going. With or without her family’s consent she would have left for — la Merica —.