Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Clairview Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

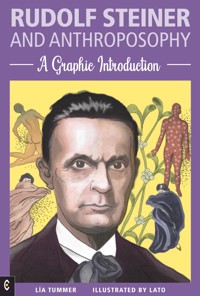

Combining Lía Tummer's lucid text and Lato's creative and playful illustrations, Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy is a highly-engaging and unique 'graphic' introduction that is suitable for both the curious beginner and the dedicated student. At the dawn of the twentieth century, Rudolf Steiner presented anthroposophy as a 'spiritual science' that expanded upon the restricted, scientific–materialist ideology of his time. Based on a profound knowledge of human beings and our relationship with nature and the universe, anthroposophy not only provides rejuvenating impulses for the most diverse spheres of human activity – such as medicine, education, agriculture, art and science – but also provides answers to the eternal questions posed by humankind, and on which contemporary science remains indifferent: What is life? Where do we come from when we are born? Where do we go when we die? What is the meaning of pain and illness? Why do people experience such differing challenges in their lives? This charming book depicts the development of a universal genius, from his childhood in the untamed beauty of the Austrian Alps to the sublimities of human wisdom; from his work as a Goethe scholar to the building of the extraordinary Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 75

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Introdution

Born of the woods

Masters

Goethe

Nietzsche

Haeckel

Theosophy

Marie von Sivers

The birth of anthroposophy

The realms of nature

The image of man

The evolution of the individual

Reincarnation and karma

The human aura

The path of knowledge

The Akashic Record

Steiner’s cosmology

The birth of human individuality

Anthroposophy and Christianity

2nd phase of Anthroposophy: the artistic impulse (1910-1916)

The ‘drama mysteries’

The Goetheanum

Eurythmy

3rd phase of Anthroposophy: practical applications (1917-1925)

The threefold structuring of the Social Organism

The Waldorf schools

The Waldorf method

Therapeutic education

An anthroposophical approach to medicine

Bio-dynamic agriculture

The Community of Christians

The Goetheanum fire

1924 to 1925

Anthroposophical organisations

Bibliography

Index

The Authors

Introduction

1900... One hundred years ago, when Europe first began to live by electric light, to communicate via telephone and telegraph, to travel by car, electric tram, airplane, and to be dazzled by the ‘magic’ of cinema...

...when, exultant, Europe celebrated her technological achievements at the foot of the new tower...

...and anxiously buried itself in the existential vacuum of ‘the end of the century’, reading Zola, Tolstoy, Shaw, Ibsen, and discussing the theories of Darwin, Haeckel, Marx...

Rudolf Steiner began to expound his very personal ‘path of knowledge’: anthroposophy.

The explosion of human creativity at the end of the nineteenth century represented the climax of the materialist concept of the universe, inaugurated by the ‘scientific revolution’ of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

So radical was the revolution produced by Galileo in the history of culture, that his era is seen as the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Modern Age—the ‘day the universe changed’.

Science focussed its attention on matter and movement...

...and thus achieved a vertiginous and successful ‘conquest’ of substances and the forces of nature.

At the end of the nineteenth century Rudolf Steiner had a broad knowledge and a full understanding of the importance of scientific achievements.

Yet, on the other hand he sought to restore the spirit as part of human and cosmic reality.

The world, trained for centuries to completely separate science and religion, knowledge and faith, body and soul, matter and spirit, did not accept that integration.

In the seventeenth century Galileo had had to explain to humanity that there is an infinite universe beyond the firmament that, until then, was believed to be the limit of space. In the twentieth century Steiner tried to explain to humanity that there is also a reality beyond the ‘firmament’ that modern man sees as the limit of life.

Just as the Church felt threatened by the ‘revolutionary’ ideas of Galileo, fighting him in life, and ‘ignoring’ him for centuries, so the academic world has managed to virtually ignore Rudolf Steiner for the last hundred years.

One hundred years have passed...

...and effectively not only is Rudolf Steiner listened to with growing interest, but many of his proposals have been used to reform a number of areas of human endeavour: education, medicine, agriculture, architecture, art, religion, social organisation, etc. The success of diverse initiatives demonstrates that anthroposophy is not a mystical and abstract mental construction, but a cosmovision able to enrich human life, even in its most practical aspects.

Born of the woods

Towards the end of his life, although already ill, Rudolf Steiner began to write his autobiography:

As a young man, Rudolf Steiner’s father had travelled through the woods of his native land as a hunter in the service of a Count. On meeting Franziska Blie...

Over the years—during which time a daughter and another son was added to the family—the Steiners were sent to different stations in the same Austro-Hungarian region.

The father’s work formed part of the family’s daily life.

Young ‘Rudi’ did not miss the arrival or departure of the few daily trains that brought different characters from the village and its surroundings, including the Count from the nearby castle, along with his entourage.

He was also captivated by his father’s telegraphic duties which he learned to carry out as a child.

Since Johann’s salary was modest, the children had to share the household chores and the work in the orchard.

The parents were always ready to spend the last of their savings for the good of their children.

Rudolf Steiner grew up, therefore, in an austere atmosphere, surrounded by unspoiled nature, in small railway towns buried amidst the greenery of fields and woods, framed by the snowy peaks of the Alps on the horizon.

He also collected wood with the local inhabitants, simple and unpretentious people who were always cordial, always ready to chat.

The village school, where a schoolmaster taught five grades simultaneously, could not teach Rudolf much more than reading. However, thus armed, he eagerly went forth to conquer the world of knowledge. He began when he was just eight years old, when a geometry book fell into his hands:

When Rudolf Steiner was eleven, his father, who wanted a ‘solid’ future for his son, sent him to the secondary school in the nearest town.

There Rudolf felt intense affinity with the clear and logical structure of mathematics.

To be able to follow the rhythm of the classes and satisfy his passionate interest in all subjects, he had to devote his free time to making good the deficiencyes with ehich his primary schooling had left him.

He began to give private lessons to his schoolmates, to help to pay for his studies.

It was the time of the first ‘pocket book editions’ and his earnings allowed him to purchase the works of the great philosophers. He studied them fervently.

Since the history classes at school did not live up to his desire for knowledge, Steiner re-bound his history book interweaving among its pages those of Kant’s The Critique of Pure Reason in order to be able to read, re-read and ponder it during history lessons.

His school, which was mainly technically oriented, did not teach Greek or Latin and so Steiner learned those languages on his own. He also began to prepare himself in all the subjects his private pupils needed to learn—including even accountancy.

In order that his son would be able to study at the Technical University in Vienna, Johann Steiner asked for a transfer to a place near the capital, although this was less convenient and agreeable for him. His son’s exceptional aptitude for mathematics reaffirmed the father’s wish that Rudolf should follow a technical career.

When he began his university studies in 1879, Rudolf Steiner registered for biology, chemistry, physics and mathematics. At the same time, he attended classes in philosophy and literature with the great teachers of the time. He never abandoned his intensive reading and research, especially into themes that caught his interest.

At that time he felt committed to seeking the truth through philosophy.

He would study mathematics and natural sciences, but to establish a link with these topics, he would base his results on a reliable philosophical foundation.

According to what Rudolf Steiner related much later, he was seven years old when he saw the first tenuous manifestations of a world not perceived with the physical senses. At that time a relative—who-he learned later had just committed suicide in a remote place—presented herself to him and begged him to protect her. The boy immediately understood that this was not a physical presence: it was no more than the first indication of a very exceptional clairvoyant ability that deepened more and more throughout his life.

From that first experience Steiner intuited that if he related what he perceived so clearly in his inner world, he could not count on the approval of his elders.

Rudolf was baptised in the village’s Catholic church and had his first religious experiences as an acolyte.

He learned to keep silent. With great fortitude and equilibrium he began his solitary inner journey at an early age.

Masters

It was not until he was eighteen that Steiner met someone with whom he could share his inner experiences:

The dialogue with the ‘master’ strengthened his conviction that he would only be able to harmonise his own inner experiences of the spiritual world with the materialist concept of his surroundings when the intellectual consciousness of his time could become his own. Only if he mastered the forms of reasoning of the ‘scientific method’ and became fully aware of the limitations of the scientific concept of the universe could he speak to the spirit of his contemporaries.

Steiner then redoubled his efforts to acquire a comprehensive mastery of the most varied areas of scientific knowledge.

Goethe