4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Honno Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

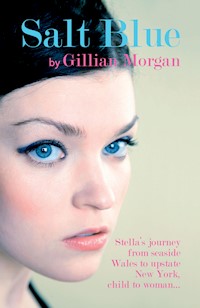

Stella lives on the Welsh coast but longs to break away from the confines of rural life in the '50s. Funded by an unexpected windfall she flies to America in search of her dreams.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

SALT BLUE

by

Gillian Morgan

For my mother, Emma and Kate, my husband and my grandchildren, with my heart and my soul, with my love and my passion. Thank you to Honno editor Caroline Oakley for her advice and guidance.

Colour speaks to the soul in a thousand different ways

Oscar Wilde

Contents

SALT BLUE

Chapter 1

The morning light is as clean and blank as a frost-bleached linen sheet. Rinsing my cup under the tap I linger over the tingling sting of hot water on my fingers. I smile at my reflection in the fretwork mirror above the sink and say ‘Hello’, a tip I read in Woman’sOwn magazine. The article was about receiving back what you give out, I think.

When asked, I call myself an ‘Accounts Manager’. I file this liberality with the truth, under the heading ‘Creative Accounting’. Viewed another way, it is refraining the picture. Illusion I understand, reality requires effort. Actually, I am an accounts clerk for ‘Bertie B. Perkins, Timber Merchants, Stanton and Gosford’.

In celebration of the weekend I have chosen an angora cardigan, which I knitted myself, in a sparkling concoction of Carmen pink and brandy wine. The colours shimmer, compelling as a pulse of energy. Wearing it back to front gives me ‘twice the looks and double the wear’, as advised by WomanandHome’s fashion editor.

Other ideas for ‘ringing the changes’ featured a beret and a bunch of woollen pom-poms. Fastened with a tiny golden safety pin, this is the way to start the week with a flourish. (‘Take care to conceal the pin inside the beret,’ the fashion editor cautioned.) Tartan rosettes, velvet bows, a Scottie dog brooch and a bunch of felt flowers in ‘glorious’ spring colours would brighten both the beret and the day.

I might have knitted a cap to match my cardigan if I had not promised Betsi Sylvester a gift for this morning’s raffle at the ‘Come and Buy’. I finished the bedjacket last night, half an hour past midnight.

The thirty-six-inch bust size used ten ounces of Emu three-ply Baby Wool in sugar pink. I saw the pattern in PrettyGiftKnitting – 20 super money-saving designs – women’s illustrated gift booklet number two, which was free. The lace pattern was intricate and, even for a fast knitter like myself, it took a weekend plus five evenings to complete. Without the crochet shell trimming, which was not included in the pattern, I would have been quicker but I like adding my signature, which is the surprise element. I wrapped the jacket in a cocoon of tissue paper and tied it with silk ribbons. Deciding it was pretty enough for a bride to wear on her honeymoon night, I tucked a velvet pansy into the bow for good luck.

Included in the pattern book was a striped tea cosy, using pretty oddments (scraps of mismatched old wool), a ‘cosy hot-water bottle cover’ and a pair of ‘slipper sox’. The socks needed a pair of leather soles to complete them, which could be ‘purchased for only seven and sixpence’ (the same price as a pair of slippers in the window of ‘Oliver Evans, Boot Shop’).

As I pondered the economics of making the slippers, I came across an article on psychology, arguing that the process is more important than the end result. Viewed this way, knitting should be regarded as a means of enjoyment rather than an economical activity. I like the feel of wool playing through my fingers, plastic steel or bamboo needles in my hands, but if I am dissatisfied with the end result I scrap it, however much I enjoyed making it.

One of my other patterns has instructions for a ‘winter Parisian coat for a smart dog’, (three ounces of double knitting wool to tone or contrast with the colour of the dog’s own coat, plus one pair number seven Aero knitting needles for the medium size) but there is no one in this town who I can think of right now who owns a poodle.

My new rubber Playtex roll-on creeps up my thighs again, so I yank it down. It took a whole tin of talcum powder to dust my stomach and hips before I had any chance of wriggling into it. Mike Price, who ran a fish stall in the market and wore a beret and who is now the area rep for Yardley’s Lavender and wears a suit (minus the beret), plus slip-on shoes, gave me a free sample of talc, enabling me to be lavish. ‘MikePrice’, my mind pauses to snarl over the name.

A few weeks after Mike had given me the sample I saw him parking a flashy blue ‘Mayfair’ saloon car outside the Town hall.

‘Nice car,’ I called, not meaning to stop.

‘Can I give you a lift somewhere?’

‘No thanks. I’m nearly home now.’

‘I’ll take you for a spin at the weekend then. We could go to Tafarn Y Sinc or anywhere you like. You say. How’s about it?’

I shook my head. Mike did not interest me, new car or not. ‘Look.’ He’d locked the car and was standing beside me now. ‘You and I know each other and I was thinking,’ (his voice was barely audible) ‘I was thinking, like, I am clean and you are clean and we could, you know,’ and he nudged my shoulder and even if I had not heard what he’d said, I would have understood the nudge. I forced myself to look at his face, flushed and almost triumphant. If I had been a good spitter, he would have had a gobbet straight in his left eye. Swift as a dervish, I spun around on my heels, my footsteps pulsating in my ears, like the tattoo from a drumbeat. I could still hear Mike’s petulant voice, ‘No need to be hoity-toity with me.’

Thankfully, apart from us, the street was empty, the town silent as a glittery morning on a Christmas card.

That was a while ago. Seeing the empty tin of talcum powder now, I aim it at the waste paper basket. If Mike were here, I might ram it down his throat but the thought vanishes and I think of Connor. The smell of talcum powder gives way to diesel oil and tractor tyres and I feel better immediately.

There’s a brooch, china roses, blue forget-me-nots, devilish-sharp, lime-green leaves, that might look good with this cardigan, but if I see Connor and his lips touch mine, ever so lightly, the brooch might scratch his chin, so I leave it in the box.

A quick glance at the back of my legs and the seams appear straight from this angle. I don’t always remember to check them, but my mother, Salli, is very fussy about stocking seams. She says the Queen always chooses seams and stockings without seams are ‘common’. Mum has decided views on most things and people sometimes say, ‘I don’t quite remember what she said, but didn’t she say it beautifully?’

All that’s left to do now is to slip into the red mohair coat, fasten the silk-ribbon buttons and I’m ready to face a cold February morning.

Chapter 2

A sigh eases from the house as I close the heavy front door behind me. My aunt, Oona, with whom I live, is the district nurse in Stanton and Gosford and the local midwife. At six o’clock this morning the telephone rang. Elvira Jones, of ‘Pen-y-Bont’, a farm about two miles from here, was in labour. After a brief conversation, Oona took the stairs two at a time and was through the front door faster than a fireball.

‘The baby’s already a week overdue, but once labour starts it will probably be rapid because it’s her third baby and she’s young’, Oona had mentioned last night.

Oona would probably have liked me to be a nurse like her, but never quite said so. As a child I had a tendency to fussiness, examining my food closely before eating it, always looking for caterpillars in the lettuce leaves, slugs in the cabbage and this fastidiousness reappeared in ideas I had about nursing. My overwhelming fear would have been to give a patient the wrong dose of medicine.

To my mind nursing is a vocation, a burning desire, like the need to be a missionary in Africa or a beautician like Miss Bishop who has a beauty salon in her front parlour, but my needs are different. I could have handled the babies’ nappies, emptied bedpans or given enemas to mothers in labour, but it was Carol Bailey’s sister, Jeannine, who helped me to make my mind up.

Carol and I were fifteen the year Jeannine qualified as a State Registered Nurse. In Jeannine’s bedroom, Carol was twirling around in an impressive nursing cape while I was admiring the sterling-silver buckles on her belt.

‘You’re thinking of nursing?’ enquired Jeannine.

‘I’m not really sure,’ I replied.

‘Your aunt is a midwife, isn’t she? I might train in midwifery later on.’

Suddenly Mrs Bailey appeared at the door with a tray of biscuits.

‘Would make a nice change from what she has to do.’

Carol’s mother had the knack of interrupting every conversation Carol and I had in that house. Personal space was an alien concept to her.

‘Bed baths,’ she whispered theatrically, her body inclined at an acute angle, leaning towards me as she edged the tray onto the dressing table. ‘For men.’

At this, Jeannine’s head jerked abruptly and she interjected, ‘That’s just one of my jobs Mum, and I always wear rubber gloves for hygienic purposes, so I never have to actually touch anything.’

Anything? The word ‘anything’ turned around in my mind, acquiring different layers of meaning with each revolution, but I said nothing, not wishing to detract from the SRN qualification.

‘She takes a little hammer with her.’ Mrs Bailey was nodding enthusiastically.

Three pairs of eyes locking onto my face felt uncomfortable.

‘Do you know why?’ queried Carol.

‘To test knee-jerk reactions?’ I answered swiftly. That cup of coffee I drank earlier must have gone straight to my brain. If Mrs Bailey’s face had not twisted into a sort of spasm, I would have thought my assumption correct. Carol was looking at me quizzically but Jeannine seemed uncomfortable.

‘Thick as broom handles some of them,’ nodded Mrs Bailey, pausing for effect and pulling her middle finger and thumb together to create a big circle.

‘She has to give a really sharp tap to get them down again.’

‘Mother!’ Jeannine’s face was redder than a roasted beetroot but her mother did not seem to have noticed. In the manner of a costermonger Mrs Bailey called raucously, ‘Small, medium or large’.

‘Mother!’ There was a murderous glint in Jeannine’s eyes, but it was too late. Gasping and choking noises started gurgling in Mrs Bailey’s throat which, coming from anyone else, would have sounded like a gasp for breath. As Mrs Bailey turned away I saw her dabbing tears of laughter from her eyes. She laughed so much, I thought she was going to collapse and Jeannine would have to demonstrate her resuscitation skills.

Looking like she’d swallowed a whole hornets’ nest, Jeannine advanced on her mother and, without more ado, grasped her elbow and steered her out through the door.

‘Mother, Stella has not come to hear this. She is considering a nursing career.’

But Jeannine was wrong, SRN or not. I was never to be a nurse now. Never. Ever.

‘Yes, all right, I’ll go, but let me just say this.’ Mrs Bailey stopped, framed in the doorway, her reddish hair wisping around her face, her sparkling grey eyes turned in my direction.

‘I never had that problem with their father, the reverse, in fact.’

She peered over Jeannine’s shoulder at me.

‘He had a little problem, my Harold, but I knew the remedy. There was no need for fancy pills and spending money on swanky consultants. No, I just tickled him up with my feather duster.’

Everyone apart from Mrs Bailey froze. The air was taut with tension, so tight you could have trotted a mouse on it. Jeannine was the first to stir and I still admire the way she manoeuvred her mother out onto the landing and down the narrow stairs of the old house and, as they disappeared, we could hear Mrs Bailey vainly protesting, ‘I was only having a little laugh, you know.’

Carol looked uncomfortable but then, like the sound of ice crackling in a frozen pond, we both burst out laughing. Carol, who was sitting on the windowsill, slipped and banging her bottom, hard, on the floor.

‘You Ok?’

She nodded and we both laughed again, this time less hysterically but in an ‘It’s Ok, don’t worry,’ way.

Downstairs, Mrs Bailey was singing ‘I’ll be With You in Apple Blossom Time’.

Carol whispered, ‘Did you notice Jeannine’s use of the term “Mother”? It’s always been “Mammie”, but now that she’s an SRN she’s a lot grander.’

After a while Jeannine returned.

‘What’s got into her since I’ve been away, Carol?’

‘I think she had a sherry earlier. I saw a sticky mark on the sideboard where she keeps it and I could smell it.’

‘Must have drunk a tumbler the way she behaved. Now,’ and Jeannine took command of the situation again, ‘I’m sorry about that but, with Dad’s death she’s gone a bit—’ and, as she was searching for the right word, Carol obliged with ‘cranky’.

Jeannine sighed. ‘Grief, neuroticism, repressed sexual desires, all tumbling together.’

Carol and I knew Jeannine’s aim was to show that now she was a nurse her understanding of life was vast. Behind her sister’s back, Carol put one finger to the side of her head and made a screwing gesture.

‘Shall we go to the Trocadero, Stell? There’s a new jukebox, we could do a bit of Elvis the Pelvis’, and she wiggled her hips.

Jeannine, ignoring Carol and probably thinking she had a responsibility towards me and the nursing profession, had a few final words to say.

‘Nursing can be varied and there are different branches, such as gynaecology.’

I nodded in what I hoped was a grateful way, but Carol got us out of there fast.

‘Yeah, all right Jeannine. Stella will think about nursing but we’re off to the “Troc” now.’

Chapter 3

Adjoining the side of our house is a shop with a blistered sign, like a medieval roadside shrine, proclaiming W.H. Sivell, Produce Merchant. In a moment of ancestor worship, I nod to it as I pass. William Halford Sivell was my grandfather and he died a month before I was born. Apart from the blood connection, I am close to him because, in numerology, his name has the number six, like mine, the animal lover’s number.

Names appear to have an inordinate importance in my family. Dadda had a saying: ‘Sivell by name, civil by nature,’ which he repeated like a bon mot.

Oona and Mum were chatting once and my aunt said the name you are born with is a truer reflection of your personality than the one you acquire on marriage. Mum laughed. ‘I’ve been a Sivell, a Randall and now I’m a Marsden. Perhaps I have a multi-faceted personality.’

‘Why was I called Stella?’ I wonder.

Mum and my aunt look at me, almost in surprise, before Mum explains, ‘Because the sky was full of stars the night you were born but you were the brightest star I’d ever seen.’

‘We’ll have one more log before we go to bed,’ Oona smiles contentedly, pushing the wood right to the back of the fire so that the sparks race up the chimney into the cold air outside, losing themselves in the darkness.

I loved those times, the three of us together, just as it had been when I was little.

I’m passing the field where Dadda kept Molly the black pony now. Brambles scribble away whole chunks of the sky but there is a clear path leading to the stable where Oona garages her green Morris Minor.

As the community hall comes into sight my heart skips a beat. Dewdrops pepper the frosty clumps of snowdrops decorating the verge but it’s Connor’s battered brown van with the rusty mudguard and the string tying the back doors together that puts a spring in my steps.

Connor and his mother run a smallholding in the Cwm, where chickens peck in the field that runs down to the stream. Although Connor and I have been seeing each other for only a few weeks, I heard Oona say on the phone to Mum the other night, ‘I know what you mean. She shouldn’t marry the first man she sets eyes on.’

It didn’t take an Einstein to know who they were talking about. I was annoyed because marriage hadn’t entered my head and I didn’t know if we were in love even. What is the test? On the radio a psychologist said that thinking too much can be a substitute for feeling, so I stopped thinking. I still couldn’t work out whether we loved each other though.

Through the corrugated tin walls of the community hall, Betsi’s voice cuts through the sharp brightness of the morning.

‘Put the long table by the wall, Con. And can you salt the path outside? Can’t have anyone falling.’

Apart from being Connor’s aunt, Betsi is the caretaker of the community hall and is holding a coffee morning to raise money for repairs. As I enter Betsi sees me from somewhere down a dark corridor and waves. Dressed in a navy jersey cardigan and matching skirt, with a red stripe around the hem, she presents a smart image.

The suit has come from Suzi Margaroli’s shop. Miss Margaroli dresses her impossibly proportioned plaster mannequin in a different outfit each week. Also in the window, an artificial branch rests horizontally across the floor and it sprouts twists of pink-and-white cherry blossom and acid-green silken leaves in springtime. On the branch, a scarf and strings of pearls are artfully twisted, and sheer stockings, kid gloves and a white handbag, similar to the ones the Queen and Princess Margaret carry, are displayed.

Miss Margaroli sells a complete look, dictating fashion in Stanton, which infuriates Mum, who says people should put their own look together. Each week Betsi pays a pound into an account she has in Suzi’s shop and, as a privileged customer, receives an invitation to view the new season’s styles. A flute of champagne ensures a jolly evening and explains why Betsi has far more clothes than she needs.

Everyone knows each other’s business in Stanton, and hears things they are not meant to, but people are very open here so there are no secrets.

‘Glad you could make it, Stella,’ smiles Betsi. ‘I’ve had plenty of help this morning. Help of the right kind. Connor’s here.’ This is said with a smile, because she knows we are seeing each other.

And then Connor appears in a jersey so tattered it might have been dried on a thorn bush, which it probably has.

His thick hair, dark on a dull day but a shade of silvery pewter when a spark of sunlight ignites it, like now, has probably not seen a comb all week. He winks at me, his face still tanned from last summer’s sun, and my heart pings.

‘Did you find the salt?’ queries Betsi.

‘I’ve got it and I’m going right away. First things first, though,’ and he comes over to give me a bear hug.

‘Are you staying?’ I ask hopefully.

‘He better had. We need him.’ Betsi’s voice is firm.

When Connor has gone, I turn to Betsi.

‘I’ve brought the jacket. Where’s the table for raffle prizes?’

‘I knew I could rely on you. Ooh, you’ve packed it beautifully. It seems a shame to open it; still, we’ll have to display it with the other prizes.’

As we’re talking two women appear at the entrance, large and misshapen, like models for a Picasso painting. A wobbly outline of pale, oyster-coloured light filters around them, throwing their silhouettes into deep relief.

In a flurry of animation, Betsi rushes to hug them, her stocking suspenders tracing a faint outline through her skirt.

‘Come on in,’ she welcomes them and, a little hesitantly, they do. The woman, dressed in a knobbly tweed coat, appears to be in her late forties, and the girl is perhaps fifteen or sixteen.

Although there is something awkward about the woman’s demeanour, the girl has a youthful assurance. A waterfall of golden hair frames her face and her complexion, pale except for her cheeks, is warmed to a bright shade of toothpaste pink by the cold morning air.

‘Stella, this is Mrs Gibbons and Hillary.’

I pull out chairs. Hillary’s whispered ‘thank you’, is accompanied by a smile, while her mother’s ‘nice to meet you’, does not sound as though it is really meant.

‘Stella has been knitting for the raffle. Show us what you’ve made Stell.’

I hold the bedjacket up, letting the light filter through.

‘Ooh, delicate as paper lace,’ declares Betsi.

Mrs Gibbons sits impassively, but Hillary leans forward, animated.

‘Do you like it, Hillary?’ Betsi takes the jacket from me and passes it to Hillary.

‘It’s beautiful. It looks really complicated. It must have taken you ages to knit?’

‘Anyone can do it,’ I say, truthfully. ‘All I did was to follow a pattern, but I had to concentrate all the time. The stitches were easy. Plain, purl, slip stitch and increase and decrease here and there.’

Hillary smoothes the shell trimming with her fingertips. ‘Is this a crochet trim on the edge?’

‘Yes, but it’s not necessary. You can leave it out.’

‘I’d love to make one.’ Hillary’s voice is wistful.

‘I’ll lend you the pattern.’

‘I can’t knit.’

‘I’ll teach you.’

I look appealingly at Mrs Gibbons, willing her to say something. When she does it is not what I want to hear.

‘Anything we need we buy.’ Her voice is clipped and she appears to address my left shoulder.

Betsi coughs, a dry rasp; my throat feels tight and I know we are sharing the same discomfort. Then a spark of inspiration arrives.

‘If you buy a raffle ticket, you could win the jacket.’

As soon as I’ve said the words I realise they are not going to buy any tickets.

‘If Hillary wants a bedjacket we’ll look in the catalogue when we get home,’ says Mrs Gibbons firmly.

The sudden hiss of the water urn comes as a benediction and, like the bubbles in ginger beer, Betsi and I rise to our feet and rush to turn it down. Unexpectedly, this provides an escape route for Mrs Gibbons too, the exit she has been waiting for.

‘We’ll have to be going,’ she announces in a relieved way.

‘Oh, not yet. Wait for tea.’ I can’t think why I’m feeling so deflated.

‘There’ll be goods on the stalls you might like to look at,’ Betsi suggests, lamely.

‘We haven’t time, now. We’ve got lots of things to do, haven’t we Hilly?’ Mrs Gibbons tugs her daughter’s arm determinedly and I wonder what interesting things these two will find to do with their day.

Though Hillary’s shoulders droop dejectedly, Betsi makes no further attempt to dissuade them.

‘Who were they?’ I wonder when they are safely out of earshot.

‘Moved opposite me about a year ago. Edna, the mother, has some nervous trouble. She doesn’t go out very much.’

‘What about her husband?’

‘He works away, though I can’t say I’ve ever seen him. They don’t seem to have any friends popping in.’ Betsi glances at her watch. ‘At least they’ve had an outing today.’

At ten-thirty the doors open and a stampede of people rushes in. On the craft table, the peg bags, teacloths, table napkins and babies’ bibs soon sell, and the cake stall, which wobbled under the weight of the tray bakes, cornflake tarts, sponges, fruit cakes, chutneys, jams and jellies at the start of the morning, is empty. ‘There aren’t enough crumbs left to feed a hungry blackbird and I’ve run out of milk,’ Betsi confides. ‘Best get on with the raffle now.’

Apart from the bedjacket; a bottle of sherry, an alarm clock and an embroidered tray cloth have been donated. And then, in front of a hushed audience, Betsi asks Connor to draw the first ticket and announce the winner’s name.

‘Mr F. Littler. Number 159 on the blue ticket. Mr Freddie Littler.’ A murmur goes around the hall, as necks crane to see if Mr Littler, the pharmacist, is here.

‘Mr Littler isn’t here, is he?’ says Betsi, ‘but I’ve seen Miss Littler this morning.’

Freda Littler waves a ticket in response.

‘The first prize is the bedjacket. Perhaps you’d like to take the sherry for your brother instead?’ suggests Betsi.

‘I’d love the bedjacket, please. My brother has said I can choose the prize if he wins. The bedjacket will be of more use to me than to him.’ A chink of laughter brightens the hall. Miss Littler accepts the prize graciously.

‘It’s lovely. I’m so glad Freddie’s ticket came up.’

‘I hope it will keep you warm,’ I murmur.

‘When I lived in Venice we called fine knitted lace “puntoinaria” or “stitches in the air”, she whispers too loudly. Miss Littler is well known for weaving Venice into as many conversations as she can.

At the end of the morning Connor, Betsi and I sweep the floor, put away chairs and throw discarded paper cups into the bin.

‘All that’s left now is to count the money, bag it and we’re done.’

Ten minutes later, Betsi pronounces.

‘Eighty pounds. We’ve plenty of money for repairs and a few extras, too. That was a very good morning’s work.’

‘Now then you two, you’re welcome to cold ham and pickles if you come home with me and I’ve a rice pudding baking slowly in the oven.’

‘Sounds delicious Betsi but not today, thank you. Anyway, you deserve a rest. Connor’s coming home with me for “frimpan”.’

‘Frimpan? What’s that?’ Betsi looks mystified.

‘That’s shorthand for “frying pan” in our house. Eggs, bacon, cheese, cold boiled potato, bacon, tomatoes if they’re in season or mushrooms; anything that can be fried.’

‘Sounds good.’

‘There’s room in the van, if you’d like a lift,’ Connor invites his aunt.

‘No, you two go ahead. I’ve got a few errands to do on my way home.’

Curled on the passenger seat of the van is a long scarf that I knitted before Connor and I became friendly.

One day, Connor called at the timber yard and asked why the scarf was that length.

‘It’s for a giraffe,’ I’d replied.

‘Why is it in that bright colour?’

‘The wool was on special offer.’

I gave him the scarf as a present and we started seeing each other. Now, Connor picks the scarf up and twists it around his hands, like a golden chain.

‘When my uncle saw me in this he said I might start warbling like a canary.’

‘It’s good for keeping the cold out,’ I protest.

‘Good for other things, too,’ and Connor wraps the scarf around our necks and pulls me so close that his mouth comes down tenderly on mine, his tongue nuzzling my lips. His kisses become more urgent and, instead of sitting there limply, like a rag doll, as I usually do, I kiss him back, properly. In a hot glow, my body responds, my face burns, not with embarrassment but with longing, ardour and desire.

Something like a tidal wave breaks over me, so that I lose my breath and see flashes of blue light. Just when I think I’m passing out the undercurrent releases me and I’m brought to the surface again. I sit, shaken.

Connor stops. His eyes search mine.

‘Ok? he asks and I nod. We both know something has made us equal, changed our relationship.

‘That was good,’ he whispers, his voice deep, pulling me roughly to him. I offer him my lips and I want him as much as he wants me.

‘Let’s go to my house,’ I say softly. He holds my gaze for a long moment, before catching my hand and pulling it down to his pelvis, looking at me enquiringly.

‘Do you understand now?’ he asks.

A feeling of foolishness engulfs me. My innocence is revealed as a handicap, a form of stupidity, proof that I know nothing about anything.

Connor’s eyes are deeply intent.

‘Do you understand that’s what you do to me, because I fancy you?’

With those words, everything is all right again.

I find the scarf and drape it so it covers my hand on his lap. Connor grins and starts the van. Maybe I haven’t split the atom but I have made a discovery: I’m in love and if someone were to offer me a dish of diamonds right now, I couldn’t be happier.

In Beauchamp Terrace, Oona has parked the Morris Minor by the kerb and is rummaging in the boot.

‘I don’t have to wait if it’s awkward with your aunt here.’

‘It’s not awkward. Come in.’

‘Need any help?’ Connor asks Oona as I unlock the front door of the house.

‘You and Stella have arrived at just the right moment. I’ve got potatoes, swedes and carrots from Pen-y-Bont. Could you take them, Con? Stella will show you where to put them.’

I pause to ask about the baby.

‘A beautiful little girl. Scrapan fach, a proper cariad.’

‘Scrapan fach’ is a term of endearment and although it means a little scrap of a thing, Oona uses it whether the baby weighs five pounds or ten.

When Oona has gone upstairs to change out of her uniform, Connor puts his arms around me. ‘To be continued later?’

‘You bet,’ and I kiss him lightly on the cheek.

While the bacon fries on the gas stove, Connor stirs the Aga into life.

His eyes travel around the kitchen, ‘This is nice,’ he says.

‘It’s all old. Oona won’t throw a thing away, calls it wasteful. Nothing’s changed since my grandparents were alive. Everything is kept as a reminder of them. Mamma’s rolling pin is in the kitchen drawer, her tapestry cushions on the chair and those are Dadda’s riding boots in the corner.’

Connor listens intently. ‘It’s the same with Mam and me, you could think we were still in the nineteenth century, our stuff is so old.’

While the bacon drains on greaseproof paper I fry the eggs in hot lard, watching them change into daisies, edged with crisp, frilly brown lace. Oona joins us and settles herself at the kitchen table, indicating to Connor to sit by her.

‘Make enough of everything, Stell, I’m starving and bring the tomato sauce as well.’

Oona eats like a horse when she’s been out on a delivery. She turns to Connor.

‘I could see lambs in one of your fields this morning.’

‘They’re not ours. We’re renting out the field, but I may buy some sheep, to diversify a bit.’

‘I’ve seen lambs, catkins and new babies, all in one day,’ sighs Oona contentedly.

‘What are they calling the baby?’ I ask.

‘“Megan”, and they’ve asked me to be godmother.’

‘How many godchildren do you have?’ Connor wonders.

‘About fifteen, I think.’

After we’ve eaten everything on the table and Oona’s found some raisin cake for us to finish, Connor offers to cut the brambles in the field.

‘I wondered what to do about them,’ admits Oona. ‘We used to have Eddie Gringridge to see to it, but the family’s moved away.’

‘I’ll have a look now, if Stella shows me what’s to be done.’

‘Let’s go through the wooden gate at the bottom of the garden out into the field.’

‘Shouldn’t take me more than a morning,’ Connor estimates, poking the brambles with a stick.

‘Mam is going to her sister’s tonight for a few hours. I’m not picking her up until ten. Like to go to the flicks?’

‘Anything good on?’ though I don’t really care. I’d watch a Battle of Britain film just to be with Connor again.

‘TheEddieDuchinStory. Some contortionist, I think,’ he adds.

Touching his lips lightly with mine, I promise to be ready by six o’clock.

Oona is tidying the kitchen when I return to the house.

‘Leave those dishes,’ I command. ‘You’ve been out since daybreak.’

‘I’ve washed everything, no need to dry them, they can drain,’ says my aunt.

I can see she’s crackling with energy, as she always is after a delivery.

‘Give my hair a brush, Stell?’

‘The brush in the hatstand in the hall Ok?’

‘Any brush.’

Oona likes having her dark hair brushed when she wants to relax.

Thick waves spring back from Oona’s low hairline and although forty-five, she has few grey hairs and her skin is good. I want to know about the afterbirth.

‘Did Elvira ask you to burn the placenta?’