Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

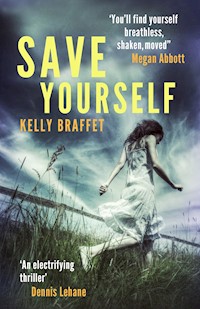

When Patrick Cusimano's alcoholic father kills a child in a hit-and-run, Patrick is faced with a terrible choice: turn his father in - destroying what's left of his family in the process - or keep quiet. But can Patrick's brother, Mike, live with the choice that was made that night? Layla Elshere was once a poster girl for purity. But when her evangelical father forces her to spearhead a campaign against her school, it compels her to question everything she's ever known. Now Layla is doing all she can to obliterate her past. Verna loves her older sister Layla, but as events begin to spiral, Verna must make the hardest choice: save the person she loves most in the world - or save herself. Save Yourself is a stunning novel about power struggles and divided loyalties, and the way in which one terrible decision can alter the whole course of your life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 515

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Kelly Braffet

Josie and Jack

Last Seen Leaving

First published in the United States in 2013 by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2013 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Kelly Braffet, 2013

The moral right of Kelly Braffet to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Book design: Maria Elias

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 323 8

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 324 5

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my mother, and for Linda

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Acknowledgments

Men talk of heaven,—there is no heaven but here;

Men talk of hell,—there is no hell but here …

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

I think I might be sinking.

Led Zeppelin, “Going to California”

ONE

Patrick worked the day shift at Zoney’s GoMart one Wednesday a month: sealed into the vacuum-packed chill behind the convenience store’s dirty plate-glass windows, watching cars zoom by on the highway while he stood still. When he worked nights, the way he usually did, the world was dark and quiet and calm outside and it made him feel dark and quiet and calm inside. When he worked days, all he felt was trapped.

So by the time he made it out of the store that evening, he was just glad to be free. His eyes were hot with exhaustion and the odor of the place lingered on his clothes—stale potato chips, old candy, the thick syrupy smell of the soda fountain—but the warm September air felt good. As he rounded the corner of the building and headed toward the Dumpsters where he’d parked, back where the asphalt had almost crumbled into gravel and the weeds grew tall right up to the edge of the lot, the car keys in his hand were still cold from the air conditioner. That was all he was thinking about.

Then he saw the goth girl leaning against his car.

He’d seen her before. She’d been in the store earlier that day, when Bill came by to pick up his paycheck. Patrick had kept an eye on her because he didn’t have anything else to do and because she’d been there too long, fucking with her coffee and staring into the beverage cases. Not that Patrick, personally, gave a shit what or how much she stole, but as long as she was there he’d felt at least a nominal responsibility to look concerned for the security cameras. Then Bill had called her Bride of Dracula and made an obscene suggestion, and she’d called him a degenerate and stormed out in what Patrick assumed was a huff. He and Bill had laughed about it, and he hadn’t thought any more about her.

But now here she was, leaning on his car like she belonged there and staring at him with eyes as huge and merciless as camera lenses. In the dimming light, her dyed-black hair and her almost-black lipstick made her pale skin look nearly blue. She held a brown cigarette even though she looked all of sixteen, her expression a well-rehearsed mixture of indifference and faint amusement. When she saw him her lips curled in something like a smile.

“Hello,” she said.

Patrick stopped. Her earrings were tiny, fully articulated human skeletons. He tried to figure out if he knew her, if underneath all that crap she was somebody from the neighborhood or somebody’s kid sister that he hadn’t seen since she was ten. He didn’t think so. “If you’re looking for weed,” he told her, “you got the wrong night. That guy works Mondays.”

“You mean your degenerate friend from this morning?” She laughed. It was a Hollywood laugh, as stale as the air inside the store he’d just left. “Hardly.”

“Whatever.” Patrick was too tired for this shit. He pointed to his car door and she moved back, but not enough. It was hard to avoid touching her as he got in. He slipped his keys into the ignition, buckled his seat belt, and rolled down the window, all the while acutely aware of the girl’s big spidery eyes staring at him through the dirty glass. He turned on the engine.

She waited, watching him.

He hesitated.

“Do I know you?” he finally asked.

“No.” She leaned down into the open window. “But I know you.” There was a ring shaped like a coffin on one of her fingers. Patrick wondered if the skeleton earrings fit inside it. She smelled sweet and slightly burned, like incense. To Patrick’s dismay her black tank top fell in such a way that he could see her lacy purple bra, whether he wanted to or not. Jesus. He looked back up at her face.

Staring at him through thickly painted eyelashes, she said, “You’re Patrick Cusimano. Your dad was the one who killed Ryan Czerpak.”

Patrick froze.

“Ryan’s family comes to my dad’s worship group,” the goth girl said, peering curiously past him into the backseat. “I used to babysit for them sometimes.” Then she saw Patrick’s face, and her blood-colored lips opened.

“Hey,” she said, but before she could say anything else, Patrick heard himself growl, “Get your tits out of my car,” and then his wheels spun in the gravel and she was gone. His heart was beating so fast that his ears ached.

The year before, on a warm day in June, Patrick’s father had come home from work two hours late, crying and smelling like Southern Comfort. His hands were shaking and there was vomit down the front of his shirt and pants. Sitting on the couch, white-faced and bleary-eyed, he wouldn’t look at either of his sons. Holy god, he’d said, over and over again. I did it now. Jesus Christ. I sure did it now. Patrick tried to get him to say what was wrong, but his father wouldn’t or couldn’t answer. Patrick’s brother, Mike, brought a glass of water and a clean shirt (throwing the dirty one in the wash and starting the load without even thinking about it) but the old man wouldn’t touch either, just rocked back and forth and clutched his head in his callused hands, chanting the same refrain: Holy god. Holy fucking shit.

It had been Patrick, after too much of this, who went to the garage and saw the dented bumper; Patrick who smelled the hot gasoline-and-copper tang in the air; Patrick who stared for a long time at the wetness that looked like blood before reaching out to touch it and determine that, yes, it was blood. Patrick who realized that the tiny white thing lodged in the grille wasn’t gravel but a tooth, too small to have come from an adult mouth. It had been Patrick who had realized that somebody somewhere was dead.

Up until that point, there were two things that Patrick could count on to be true: the old man was a drunk, and the old man screwed up. And as far as Patrick was concerned, the first priority was fixing it. When he worked the morning shift at the warehouse you woke up before he did so you could make the coffee and get him out the door. When he passed out on the couch you took the cigarette from his limp fingers. When he ranted—about the government that wanted to take his money, about the Chinese who wanted to take his job, about the birth control pills that had given Patrick’s mother cancer and killed her—you kept your cool and had a beer yourself, and you tried to sneak away all the throwable objects so that in the morning there’d be glasses to drink from and a TV that didn’t have a boot thrown through the screen. You took evasive action. You headed disaster off at the pass. You made it better. You fixed it.

Staring at the bloody car, Patrick thought, wearily, I can’t fix this.

Inside, Mike, his eyes wide with panic, said, No, little brother, hang tight, we can figure this out. Just wait. Even though there was nothing to figure out. All through that night into the gray light of dawn and on until the shadows disappeared in the midday sun, the three of them hunkered down in the living room, the old man sniveling and stuttering and saying things like Jesus, I wish I still had my gun, I ought to just go ahead and kill myself, and Mike—who would not even go into the garage, who point-blank refused—trying to force the reality of the situation into some less horrible shape. The longer they sat, the more it felt like debating the best way to throw themselves under a train. Patrick, it seemed, was the only one who realized that there was no best way. You just jumped. That was all. You jumped.

So, at one o’clock in the afternoon, Patrick called the police. Nineteen hours had elapsed between his father’s return home and Patrick’s phone call. He’d thought it through: they couldn’t afford a private lawyer, and the old man couldn’t get a public defender until he’d been charged. When the police arrived, the detective came back from the garage with a steely, satisfied expression on his face. We’ve been looking for you, he said to the old man, and all the old man did was nod.

Patrick remembered very little about what happened after that. Except that Mike said, Jesus, Pat— nobody had called Patrick Pat since he was ten years old—he’s our dad.

Well, it’s almost over now, Patrick said.

He had been wrong. It was just starting. None of Patrick’s friends had explicitly told him they didn’t want to hang out anymore; the cop who came into Zoney’s every night had never said, I’m keeping my eye on you, Cusimano; like father like son. The supervisor at the warehouse where all three Cusimanos had worked had never suggested the remaining two find other jobs (and in fact, Mike still worked there). But always, from the very beginning, Patrick had read a sudden wariness in people, as if bad luck was catching and he was a carrier. The sidelong glances and pauses in conversation that stretched just a beat too long; the police cruisers that seemed to drive past their house on Division Street more often than they once had, or linger in the rearview a block longer than was reasonable; the weird sense of disengagement, of nonexistence, when cashiers and waitresses and bank clerks who saw his name on his credit card or paycheck couldn’t quite seem to focus their eyes on him. Like he was nonstick, made of Teflon, and their gazes couldn’t get purchase.

Nothing overt. Nothing you could point to. Just a feeling. If he’d never bought the newspaper at the SuperSpeedy, it wouldn’t have come to anything more than that. He could just have bulldozed through, like Mike, waiting for people to get over it. He’d avoided coverage of the accident as much as he could. He didn’t want to see the roadside shrine, with its creepy collection of plastic flowers and cellophane-shrouded teddy bears that wouldn’t ever be played with, and he didn’t want to see the kid’s stricken mother holding a photo of her dead kid in the bedroom where he’d never sleep again. He’d bought the paper that day because his job at the warehouse had already started to feel impossible, but he hadn’t taken anything from the rack but the classifieds. It hadn’t occurred to him that the obituaries would be in the same section. Even if it had, it wouldn’t have occurred to him that the kid’s obit would still be running a month after the accident.

But he’d turned a page and there it was, oversized in the middle of all that sad muted eight-point death. Until then he hadn’t actually seen the dead kid’s photograph. Looking at it, at the kid’s gap-toothed first grader grin, he’d felt—not bad, bad was his new normal. He’d felt worse. He wouldn’t have thought that was possible.

The obit listed a memorial website, where you could make donations for the family. It took a few days for him to work up to it but eventually Patrick had suggested to Mike that they give some money. Anonymously, of course. Not out of guilt, although that was certainly part of it; more out of a sense that here was a thing, albeit a small thing, that could be done. But Mike, who had been drinking beer and watching Comedy Central in near silence ever since the accident, had only glared. For a moment, Patrick had thought his brother might hit him.

Instead, Mike had asked why the hell they would do that, since it wasn’t like the old man had killed the kid on purpose. And it wasn’t like they had any money to spare—only the old man had made fulltime union wages, and losing his paycheck had hurt them badly—and it also wasn’t like anybody was offering them free money, were they? “Fuck the kid, fuck his fucking family, and fuck you,” Mike had said. “Dad’s going to be in jail for fifteen years. They don’t get anything else.”

Determined to send the money anyway, Patrick had used one of the computer terminals in the public library so Mike wouldn’t catch him, typing in the web address with his almost-maxed credit card ready to go. He’d scrolled down the page past the kid’s picture, trying not to feel cynical about the sappy graphics and badly rhymed poetry (My broken heart can only cry, I pray to God and ask Him why) and looking for the donation link. He’d found the other one first.

Click here for more information about John Cusimano and his sons.

Gravity had done something weird just then. Patrick had felt like his limbs might float away from his body, but he clicked, anyway.

No flickering candles on this page. No sweet angels with electronic wings gently flapping. No poetry, no flowers, and most of all, no grinning first grader. The page he’d landed on was stark white, with red and black lettering: double underscore, bold, italic, and very, very angry. And it wasn’t about the old man. It was about him and Mike.

John Cusimano’s two ADULT sons, Michael and Patrick, were alone with him for NINETEEN HOURS after their father KILLED RYAN!! The car that took our Precious Baby away SAT IN THEIR GARAGE COVERED IN RYAN’S BLOOD and they DIDN’T BOTHER TO CALL THE POLICE!! THEY WASHED THEIR FATHER’S CLOTHES TO DESTROY THE EVIDENCE!! Call the Janesville County District Attorney’s office and demand that they be charged as ACCOMPLICES AFTER THE FACT!!! DO NOT LET THESE MONSTERS GET AWAY WITH MURDER!!!

There was a photo, which Patrick had already seen when it ran in the local paper, of the brothers leaving the courthouse after the arraignment. There was also a message board. Patrick had known he shouldn’t read it.

Michael and Patrick Cusimano you will burn in hell forever.

Those boys better hope they never meet me in a dark alley. Once upon a time somebody would have GOT A ROPE already.

In twenty years monsters like this will be ruling the country. This is what happens when you take prayer out of the schools.

Only one (anonymous) poster had said anything even remotely positive—I knew Mike and Patrick in high school and I thought they were nice, I am so sorry to Ryan’s family but Mike and Patrick are suffering too— and the responses had not been generous.

It is obvious you do not have children and I hope you never do!

If you think their nice your probably just as evil as they are. I notice your not using your real name.

The messages made it sound like the old man had pulled up in the bloody car, said, Hey, boys, look what I did, and the three of them had traded a round of high fives, tapped a keg, and popped some popcorn. The dislocation was dizzying. Patrick had spent almost an hour reading those messages, all about what a monster he was. He never made the donation. He knew it was unfair, punishing the kid’s family for being angry that they’d lost their son in such an ugly way. Their kid was dead, and other people’s kids were alive. Patrick’s dad was a drunk and a murderer, and other people’s dads were insurance salesmen and orthodontists and air conditioner repairmen. Fair didn’t seem to have anything to do with it.

He’d been thinking of the accident as a tragedy that had happened to all of them, Czerpak and Cusimano alike. He’d been hoping that the guys at the warehouse were just being awkward-weird, the way his teachers were when he was eleven and his mother was dying. But after seeing the website, his eyes were open. He felt every chill, noticed every look and nonlook and casually turned shoulder and half-heard whisper. At that point he’d still had a few friends, people he knew from high school and work, but within three months of the accident they’d all fallen away in a litter of voice mail messages saying We totally gotta hang out, like, soon, but not tonight and not this weekend and probably not next week but soon. By the time the old man had pled guilty to all counts and been transferred to a state facility in Wilkes-Barre, the messages had stopped. Patrick had been relieved. There was nobody he wanted to talk to.

Then it had just been Mike and Patrick alone in the house until Mike met Caro and the two of them took over the room where Patrick’s parents had slept: cleaned it out, redecorated it, filled it with the smells of laundry soap and sex and Caro’s perfume. Patrick quit his job at the warehouse and took the night shift at Zoney’s GoMart (except for that one day shift a month, which he hated). Mike worked every shift he could get at the warehouse, and Caro waited tables at a seafood place in downtown Ratchetsburg. To Patrick it felt like the three of them were planets that came into alignment once a week or so, shared a few beers and some hot wings, and then spun back out into their own separate orbits. The other world, the world he’d belonged to before that afternoon when the old man had stepped out of the Lucky Strike and decided he was sober enough to drive—that world, presumably, kept spinning, somewhere out there, but Patrick didn’t live there anymore. He’d fallen into a numb kind of stasis and after a while he couldn’t tell the difference between the long quiet nights he spent alone in the store and the long quiet days he spent sleeping off the nights. They both felt the same. They both felt like nothing.

You’re Patrick Cusimano. Your dad was the one who killed Ryan Czerpak.

That night, as he drove home from work, he hit a deer. He’d taken the back way home, down Foundry Road, which at that time of day was a green-black tunnel through the trees. It was hard to see anything clearly; headlights didn’t do any good, and the best you could do was squint and hope. Patrick had been awake for almost twenty hours. He’d left the goth girl behind him in a cloud of dust, but her voice was still in his ears. He was distracted. The world seemed like a movie scrolling by outside his windshield. Then he saw the tawny flash in his right headlight, and: thud.

His knees and elbows locked. He stomped on the brakes, steeling himself for the dreadful bounce of the wheels driving over the deer. It never came. When he pulled over to the side of the road, his chest felt tight and it was hard to breathe. For a moment he could only watch his hands clench and unclench on the steering wheel. Then he made himself get out.

He could hear the rush of traffic on the highway, but Foundry Road was deserted. In the faint glow of his own headlights, he stared at the four-inch fissure that had appeared in his bumper. There was no blood, for which he was thankful. He thought that if there’d been blood he probably would have flipped a circuit breaker and somebody would have found him by the side of the road in a few hours, twitching and drooling in a patch of poison ivy.

His legs felt weak but he walked toward the back of the car, stopped, and stared down the road, listening. He didn’t know what he expected to hear. The spastic scrabble of dying hooves against asphalt. Something. His nose searched among the smells of exhaust and scorched rubber for the heady tang of blood. But he heard nothing, and he smelled nothing. He’d just clipped it, he thought, and it had run off. Or limped off, somewhere into the woods around him to die of shock or fear or internal bleeding. And what could he do about it either way? It wasn’t a cocker spaniel; he couldn’t wrap it in his coat and race it to the nearest vet. Even if it had been lying there on the asphalt in front of him, there would have been nothing he could have done except pull it off the road so it wouldn’t get hit again while it was dying. So its death would be long and painful instead of quick and violent. A questionable mercy, at best.

The tightness in his chest grew worse. It was only a deer, he told himself. Not a jogger, not a pedestrian. Not a little kid chasing a kickball.

The air was warm and dewy and smelled like growing things. The leaves on the trees around him rustled, a gentle susurration that he found almost mocking. A drop of sweat ran down his ribs from his armpit. All at once he was so tired he could barely feel his feet. He turned around and went back to his car, turned the key with numb, trembling fingers, and drove away. Leaving the deer, wherever it was, behind.

At home, Mike’s truck was in the driveway and Caro’s car on the street, so Patrick parked in front of the house next door. He grabbed his phone from the console and the emergency twenty from the glove box, saw a few CDs on the floor and grabbed those, too. He wasn’t consciously aware that he was emptying his car of everything he cared about until he turned at the front door and looked back.

The car crouched at the curb like a piece of roadside litter, the way you sometimes saw shoes or gloves or undergarments lying forlorn in puddles of mud, growing black with exhaust as the world passed them by. He’d owned the car for ten years, since he’d turned sixteen. Even in the yellow glare from the streetlight he could see how dirty it was. Although he couldn’t see them, he knew the gas tank was half-full and the washer fluid reservoir empty. He couldn’t see the cracked bumper, either, but he could feel it throbbing like a bruise.

Inside the house, he dropped his keys on the little table next to the door. Dead deer or no dead deer, he had no intention of ever driving the car again.

That night was one of those planets-in-alignment times. Four hours later he was steadier, drinking beer and watching television with Mike and Caro. She was sitting on his brother’s lap, still wearing the white blouse and black skirt she waited tables in; Mike hadn’t even taken off his work boots yet. His hand was tucked between Caro’s knees. Patrick knew without being close to them that Caro smelled like fish and hot butter and Mike smelled like the picnic table out behind the warehouse, sweat and dirt and cigarette smoke. Patrick was watching a horror movie; not a very good one. On the screen, a mutant bear tore off a hiker’s arm. The blood spatter hit the camera lens. It was that kind of movie.

“Come on, man,” Mike said. “Normal people don’t watch this shit. This is sick.”

“Change it if you want.” Without much interest, Patrick tossed over the remote.

Caro caught it and put on some sitcom with a laugh track. “You’re in a good mood. Tough day at the office, dear?”

Your dad was the one who killed Ryan Czerpak. “Same shit, different day,” he said. “I hit a deer on the way home.”

“Grab me another beer, will you, babe?” Mike said to Caro.

She reached into the cooler behind them, pulled out a can of beer, and shook away the melting ice before handing it to Mike. “Did you kill it?”

“I don’t know. It ran off.”

“It’s a deer. What’s the big deal?” Mike cracked open the can.

“The big deal is that it sucks to kill something,” Caro said.

“I see a dead deer, I think jerky.”

She bit Mike’s ear. “That’s because you’re a jerk.”

“I’m your jerk, though,” Mike said, and kissed her. Patrick looked away. He liked Caro and she made his brother happy, but nothing said you don’t exist quite like being in a room with two people who couldn’t keep their tongues out of each other’s mouths. The fake family on the television screen was now embroiled in some sort of wacky misunderstanding involving a tray of lasagna and he missed the mutant bears.

“So, Patrick, did you mess up your car?” Mike said, finally.

“My sources say yes. It’s all over the road.”

Mike nodded knowingly. “The alignment. You want me to take a look?”

Caro slapped his arm. “You said you were going to get me a new battery.”

“I will, I will. Quit nagging.”

“You’re the one who has to drive my sorry ass around when my car won’t start.”

“I love your sorry ass,” Mike said, and kissed her again.

“I could not be here for this,” Patrick said. “That would be okay.”

“Patrick, you need a girlfriend,” Caro said sternly. “You’re the loneliest bastard I’ve ever met.”

“Right. Because all of my problems would be solved if I just had more sex.”

“I didn’t say sex. I said girlfriend.”

“You might not believe this,” Mike said to her, “but there was a time when my brother was a devil with the ladies. He used to take them to this graveyard, up in—where was it, Cranberry?”

Patrick’s jaw clenched, hard. He forced it to relax. “Evans City. And I only did that once or twice.”

“They shot some movie there,” Mike told Caro.

“Calling Night of the Living Dead ‘some movie’ is like calling a ’sixty-eight Camaro ‘some car,’” Patrick said.

“You don’t know shit about cars.”

“You don’t know shit about zombie movies.”

“Now, boys.” Caro curled an arm around Mike’s shoulder. “I didn’t know they made movies in Pittsburgh. Is it still there? Can we go see it?”

Mike shook his head. “I’m not driving all the way up there. You want to see a cemetery, I’ll take you out to St. Benedict.”

“Did they make a movie there, too?”

“No, but that’s where my mom is buried.”

“We can do that if you want. But I want to see the movie one.”

“It’s really not that exciting,” Patrick said. “It’s just a cemetery.”

“Exciting is not the point. The point is that we never go anywhere and we never do anything and all this will cost is gas.”

“Gas is expensive,” Mike said. Caro’s face went flat and he pulled her closer. “Cheer up, girl. We’ll go out tomorrow night. Do something fun.”

“Sure,” she said, and gave him a limp smile.

Patrick got quite drunk that night. Drunker than he meant to; drunker than was warranted, given that it was just a Wednesday and he was just in his living room and tomorrow he had to work (although not until midnight). Mike and Caro drank, too, and eventually Patrick noticed that the hand Mike was keeping between Caro’s thighs was becoming less and less appropriate, so he stumbled upstairs to bed. It wasn’t long afterward that he heard the thump-and-giggle sound of Mike carrying her upstairs to their room and the double thud of their bedroom door being kicked shut. Caro said words he couldn’t quite catch and Mike said, “Oh, god,” but it was more of a moan.

Patrick fumbled for a CD. It turned out to be Metallica and the empty space in the room filled with noise like it was water. He was drunk, he was drowning, he was sinking into blackness. He went down gladly.

There were a few times the next morning when he was dimly aware of Mike or Caro moving around the house: a door closing, the sound of the television downstairs. Once, he dozed off to a fragmented dream of tawny hide flashing in headlights, dream-felt a thud, and woke in a startle with his heart pounding. But he fell back asleep again in a few minutes.

When he woke up for real everyone else was at work. He did some laundry and made himself an over-easy sandwich with a slice of American cheese, hungover enough that the previous night felt far, far away. He had no desire to bring it closer. After he ate his sandwich, he decided he wanted a Coke and got as far as grabbing his keys and stepping outside. Blinking in the noon sun, he saw his car parked where he’d left it, in front of the house next door. A thick layer of grime coated the windshield. Everything he’d forgotten snapped back into brutal clarity and he looked at the car and thought, no, hell no, he didn’t need a Coke that badly.

He spent the day doubting that he really had the gumption to walk to work that night, but when he stepped outside at eleven thirty, one look at the car made his skin crawl and the night was warm-ish, so he set off on foot. It wasn’t entirely unpleasant. The dingy strips of paint peeling off the houses on Division Street didn’t show so much at night, and when he got onto the highway and away from the streetlights, the wedge of moon blurred the speed limit signs into afterimages. He was between haircuts at the moment, and the feel of the breeze moving the long strands against his neck—like gentle fingers—almost made him want to never cut his hair again. There was a dreamy quality to being out this late, when everything else was shut down: like time had stopped and the rules no longer applied.

When he walked through the door at Zoney’s at midnight, the blue-white fluorescents frizzled that nice blurry dreaminess into nothing. The back of his candy-striped work shirt was damp with sweat and his hair stuck to the nape of his neck. The guy he was relieving signed off on his deposit and left; Patrick counted the drawer, shoved it back under the register, and wiped the counter clean. It felt like he’d only been away from the store for a few minutes, like he’d stumbled through some reality loophole to a universe that was all Zoney’s, all the time.

By the time the cop who stopped in every night for a scratch ticket and a Snickers left, Patrick had downed two cartons of chocolate milk, and no longer felt perched on the edge of his own grave. If it had been a weekend, a steady stream of drunks would have trickled in through the early hours, with a surge around four when the bars closed and then nothing much until sunrise. But on Thursday nights, even people who drank their paychecks were back in bed by two so they could drag themselves through the next day to get to the real weekend. The highway outside was so deserted that he could have stretched out in the middle of it for a nap. The classic-rock station playing in the store was automated, all music and condom ads. When Patrick had first started working at Zoney’s, there’d been a CD player, and he’d played Black Sabbath while he worked. The loud and angry was a nice antidote to the quiet and bright and made him feel more him, as if, candy-striped shirt or no candy-striped shirt, he could broadcast this little piece of his soul to every poor schmuck who came through the door for a Red Bull at three in the morning. It got people’s attention, reminding them that the world was real, that it was alive. But one morning he forgot to take the CD home with him, and when he came in for his next shift, the CD player had been replaced by a note from the manager about appropriate work music. So that was that. One more fragment of his being shaved away, and all he got in return was minimum wage and a nearly perfect command of every Eagles lyric ever. You could check out anytime you liked, but you could never leave: truer words, man. Truer fucking words.

Things started to pick up around six, and by seven he’d fallen into a kind of waking coma of jingling change and beeping cash registers. When a voice in front of him said, “I brought you coffee,” he woke with an unpleasant start.

On the other side of the counter, paper cup extended, stood the goth girl. Today she wore a purple dress with a half dozen belts hanging loosely from the waist. Her boots were big and cartoonish and she’d probably had to drive to Pittsburgh to buy them. The bag over her shoulder looked like it had come from a surplus store.

She smiled. “A peace offering, okay?”

Patrick didn’t smile back. He looked at the impatient-looking woman in panty hose and sneakers in line behind her, and said, “Come on up.” As he rang up the woman’s Slim-Fast and got her a pack of Capri cigarettes, the goth girl stood and watched with an almost anthropological interest.

“What to avoid becoming, exhibit A,” she said, when the woman was gone.

“Fuck off.”

The girl rolled her eyes. “Relax. Do you want milk and sugar in your coffee? I left it black because I didn’t know. It’s the good stuff. From Starbucks.” When he didn’t move to take the cup she grimaced. “Look, you’ve got me all wrong. I’m not going to go psycho on you. It’s not your fault Ryan’s dead. You didn’t kill him.”

This wasn’t happening. He was not standing here among the raspberry-coconut Zingers and jerky sticks, earning minimum wage and listening to her say these things. “Next,” he said, and sold a large coffee and a chocolate cream doughnut to a fat guy who didn’t need any more doughnuts.

“Let’s start over,” she said, smoothing her already impeccable black hair. “My name is Layla. Like the song. You know: you got me on my knees.”

This girl. This little high school kid with her stupid boots and her Addams Family wardrobe and her skin as white and floury-looking as unbaked bread. Pillsbury goth girl, just out of the can. He wished she’d go cut herself or snort Ritalin or do whatever the hell goth girls did when they weren’t blocking his counter and saying things like It’s not your fault Ryan’s dead. You didn’t kill him.

He sold five dollars’ worth of gas to a kid in a Slayer shirt and then there was nobody left in the store but the two of them. The girl leaned her elbows on the counter and said, “I looked your yearbook picture up in the school library. You had a really dumb haircut back then.”

Patrick cashed out the register, taking the keys to the storage cabinet from behind the bill tray. He unlocked the cabinet, pulled out a carton of low-tar menthol something-or-others, tore it open, and started stuffing the packs of smokes into the overhead racks. “Why?” he said.

“I wanted to see what you looked like in real life. I have kind of a thing for monsters. Are you going to drink your coffee?”

The paper cup with the Starbucks logo sat on the counter where she’d left it. “I don’t drink coffee.”

“Oh.” Her face seemed to fall. “Do you want something else? Gin and tonic?”

Patrick finished the cigarettes and slammed the cabinet door closed. “I want you to leave me alone.”

“People think I’m a monster, too. Zombie Girl, Freakshow, Bride of Dracula—your friend yesterday wasn’t exactly the first person to come up with that one, you know.” She shrugged. “I don’t really care. If they didn’t call me Zombie Girl they’d call me Geek Girl, or Blow Job Girl, or whatever. I used to be Jesus Girl, if you believe that.” There was a display on the counter of plastic toy cell phones filled with gum. Picking one up, she pressed a button on the side, and the toy went Brrreeeep. “Hey, are you doing anything this afternoon?”

“Why? Do you have an open slot in your stalking schedule?”

She laughed. “Funny. No, monster, if I was stalking you, we’d be having this conversation in your living room. I just thought maybe if you weren’t doing anything, and you wanted some company, we could hang out, that’s all.”

Patrick stared at her, incredulous. Before he had time to say anything the bell over the door jingled again and this time it was Caro. Her unwashed hair was pulled back in a messy knot. Mike’s Penguins key chain dangled from the front pocket of her cutoffs. She pointed toward the back of the store, said, “Coffee,” and disappeared behind the Hostess display.

The goth girl lifted one perfectly penciled eyebrow, her white-powdered face faintly amused. “Busy after all, are we?” she said, then lifted the toy phone up, hit the button—Brrreeeep— and dropped it into her army-navy bag.

“Hey,” Patrick said, but she had already turned and walked out of the store. Caro emerged from between the aisles with a large coffee in one hand.

“Your store does not have good coffee. I ate a doughnut back there.” She yawned.

Patrick bit back his annoyance. “That’s cool. People have apparently given up paying for things around here, anyway.”

“Don’t get snippy. I didn’t say I wasn’t going to pay.” Caro handed him a five. “Who was your shoplifter, Marilyn Mansonette? You didn’t try very hard to stop her. Do you know her or something?”

Through the window, he watched the goth girl climb into her big shiny car, one of those new round retro-modern things that looked like a cartoon hearse. As the driving lights came on, a pounding bass line kicked in. Nu-metal techno shit. “Not even a little bit,” he said, and made Caro’s change.

“That’s some car she’s driving,” she said. “Somebody is certainly Daddy’s best girl.”

He wanted to change the subject. “What are you doing out this early, anyway?”

“It’s not voluntary.” She folded her arms on top of the cash register and rested her chin on her wrists. The top of her head bobbed with each word. “Mike let me take his truck since my stupid battery has been so flaky lately. I just drove him to work. You can get him tonight, right?”

“Nyet.”

“Fuck you, why not?”

Because driving scared him and he didn’t want to do it anymore. “My car’s out of commission. From hitting the deer. I told you.”

She blinked her green eyes and frowned. “You didn’t say it wasn’t working at all. How did you get here?”

“Walked.”

“You’re not going to turn into that creepy long-haired guy who walks everywhere, are you?”

“My hair’s not that long.”

“It’s getting there.” She yawned again, bending her face down toward her shoulder to cover her mouth. “You should have asked for a ride.”

The door bell jingled yet again. This time it was an old duffer wearing a flannel shirt that looked as ancient as he did. “Need a Match 6,” the duffer said, pulling a scrap of paper with some numbers scrawled on it out of his pocket.

Caro stepped back. “I’ll tell Mike to call you.” Then she lifted a hand and left. The duffer started reading off his numbers and Patrick punched them in. As he waited for the ticket to print, he happened to glance out the big plate-glass window and see Caro. He watched as she put her coffee cup down on the running board of Mike’s huge jacked-up truck, pulled the sleeve of her sweatshirt over her hand, and reached up to open the door. Then she freed her hand, picked up her cup, and hoisted herself nimbly into the cab. She didn’t even spill the coffee. It was impressive.

The lottery machine whirred. Patrick looked back at the old duffer. His eyes were the same place Patrick’s had just been. “Wouldn’t mind a piece of that,” the duffer said.

“You want her number?”

The duffer laughed, his mouth opening wide to show stained teeth and a yellow tongue. Patrick asked him if he needed anything else.

“That’ll do me,” the duffer said.

…

Bill had the next shift. A few minutes before he was supposed to arrive, the phone rang. “Dude,” he said, sounding at least as hungover as Patrick had been the night before. “Cover for me for a few hours.” And extra money was extra money, so Patrick did. By the time he got home, it was close to noon. Caro was at work and the house was empty. He took off his candy-striped Zoney’s shirt, dropped it on the floor next to the armchair, and dropped himself onto the couch. ESPN Classic was showing an old Pirates game; it was the playoffs, and the Pirates were winning. The last time that had happened, Patrick had been nine. His mom had been alive and his dad had only been a social drunk. He vaguely remembered this game, these players. Baseball cards at recess, or something.

He fell asleep before the fifth inning and woke up to a clattering crash. Which turned into a fast riffing guitar, and the Zeppelin song he used as his ringtone. He grabbed for his phone and pressed buttons until the noise stopped. “Hello?”

“I didn’t know your car was that bad,” Mike said.

Now the TV screen showed a man in a cowboy hat clinging to a bull the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. Patrick groped for the remote. The announcer’s cornpone accent was the most annoying sound he’d ever heard. “Yeah,” he said, still groggy. “What’s up?”

“Caro’s phone is dead. Probably out of minutes. When she gets home, tell her I picked up a double, so she doesn’t need to come get me. I’ll get a ride with Frank tomorrow morning.” Patrick heard a shout and a laugh in the background. Mike was calling from the phone in the warehouse office. “She might be pissed. We were supposed to go out tonight. Tell her something nice for me, okay?”

“Tell her yourself,” Patrick said, but Mike had already hung up.

Patrick looked at the clock on the cable box. He’d been asleep for six hours, but it wasn’t enough, and his skull felt stuffed with cotton. On TV, some poor son of a bitch from Tulsa got dragged around the arena by his left arm and the cornpone announcers said, Good golly he shore did get hung up there dint he and I tell you what that is one tough Okie.

Patrick changed the channel.

He was watching a slasher flick—Oh, no, the group of attractive young people trapped in the department store were saying to each other, however will we escape the murderous psycho who is creatively and elaborately killing us one by one?—when he heard Caro fighting the lock on the front door, which stuck. “The minute we have some extra money,” she said, as soon as she got inside, “we’re fixing that door. It’s impossible to open.”

“Keeps out the undesirables,” Patrick said, muting the television.

“That’s the antisocial recluse we know and love. I brought food.” Caro put two foil take-out containers on the coffee table and then flopped down next to him on the couch. She looked like hell. Her makeup was smudged and caked under her red eyes. Patrick knew it was just the long day she’d had, but she looked like she’d been crying. Picking up one of the containers and passing it to him, she said, “That was a day. That was most certainly a goddamned day. Here, eat. I have to go get Mike.”

“No, you don’t.” Patrick peeled the cardboard lid off the container and looked inside: penne and chicken in some kind of white sauce. He picked up a few pieces with his fingers and shoved them into his mouth. “He took an extra shift. He’ll be home in the morning. He said to tell you sorry he couldn’t take you out tonight.”

Caro stuck her tongue between her lips and blew a raspberry. “I’m dead on my feet, anyway. You could use a fork for that.”

“I don’t have a fork.”

“So go get one.” On the television screen, a pretty girl was pounding on the inside of the department store display window, trying to get out. Caro unlaced her shoes. They were the practical, solid, spend-all-day-on-your-feet variety but she still winced as she pulled the first one off. “I hate my job,” she said, conversationally. “My feet feel like they’ve got nails through the bottoms and I spend all day watching things get boiled alive.” She eyed Patrick, sitting on the other end of the couch. “I don’t suppose you want to move and let me stretch out, do you?”

“I was here first.” He ate another three fingers’ worth of pasta. The sauce was kind of congealed.

“You’re such a youngest child.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Constantly fighting for position.”

“Bullshit.”

“I’m just telling you the theory.” Caro reached down, flipped her shoes upside-down on the floor, and then rubbed the ball of her foot. She had a hole in her sock. “They’ve done studies about this stuff. Like, Mike is solid and respectable, because he’s the oldest, and had the most responsibility growing up, and you’re the youngest, so you always have to prove yourself.”

“Complete bullshit. What about you?”

“Doesn’t apply to me. I was raised by wolves.” She swung her feet up into his lap, narrowly missing his pasta. “If you don’t want my gross waitress feet in your face, you’ll move.”

“I have an unusually high tolerance for gross.” A bucket of acid fell onto the prettiest and most nubile actress in the movie, causing her face to melt with an excruciating slowness. The fake skull under her flesh looked a little plasticky. Caro made a face. “Nice special effect, huh?” he said.

“I wish those lobsters were just a special effect.” Shuddering, she tucked her feet underneath her. “Scrabble scrabble. Can we watch something happier?”

“Like what, sports? Earlier I fell asleep watching a Pirates-Braves game from the ’ninety-two playoffs and woke up to some guy getting his arm torn off on the back of a bull. How is that less horrible than this?”

On-screen, the nubile actress’s boyfriend was wading through the puddle of her dissolved flesh. Caro stood up. She pulled at the elastic holding her ponytail, and her hair, which was the color of sun shining through a bottle of cola, fell around her shoulders. “Watch your movie, sicko. I’m going to go take a shower and wash the dead fish smell out of my hair.”

“I like the dead fish smell.”

“Nobody likes the dead fish smell,” she said, and went upstairs.

Caro had moved in a month or so after the old man went to prison. Mike had brought her home from a bar, and Patrick had awakened the next morning to a series of unmistakably breakfast like smells drifting up the stairs. Coffee, bacon, French toast. He’d come down to find the two of them sitting at the table, a third place set for him. Caro had looked vaguely embarrassed and Mike had looked happier than he had since before the accident.

She followed me home, he’d said with a grin. Let’s keep her.

And, sure enough, by the end of that first week, her toothbrush was next to the sink and her tampons were in the medicine cabinet. To his relief, Patrick liked her. She was smart and funny and not obviously crazy; also, she could cook, and she liked folding laundry, and she didn’t ask questions. Or answer them, really. He knew she was from Ohio, and he knew she did strange things sometimes, like turning her shoes soles-up on the floor or pulling her sleeve down over her hand before touching a doorknob. She kept books under the couch cushions not secretively, but mindlessly, as if out of long habit. Once, when he’d asked her about the sleeve thing, she’d turned scarlet and ghost-white in rapid succession and the whole set of her body had changed, curling into itself as if she were trying to shrink. He’d never asked her anything like that again.

She came back downstairs wearing a T-shirt and an old pair of Mike’s cutoff sweatpants, returned to the other end of the couch, and tucked her feet underneath her again. She’d washed off the caked, smeary makeup, and her cola-colored hair was clean and pulled back in one of those plastic clips. Now she smelled girly, like conditioner or something. Sweet but not cloying.

“Did you really used to take girls to have sex in that graveyard?” she said.

By now, the last two survivors in the department store were crawling through a heating vent. “Not all girls. It had limited appeal, although you’d be surprised how many went along with it.”

“You’d be surprised how little I’d be surprised. When was the last time you were up there?”

“I guess I was—seventeen? Eighteen, maybe.” He hadn’t been to Evans City since high school. After that, he’d just brought his girlfriends back to the house. The old man had never cared.

“Who was the girl?”

“Debbie Mayerchek. She still lives behind us. Me and Mike used to tie her to trees when we played cops and robbers.”

Caro’s eyebrows went up. “Your version of cops and robbers involved tying girls to trees?”

“She was a hostage.”

“And I thought my childhood was screwed up. You guys were into bondage. Was she your girlfriend?”

“Nah, we just went out a couple of times.” And in fact, after the night he’d taken her to the graveyard, he’d never called her again. Or spoken to her in school. Or spoken to her, ever.

“Was she into horror movies?”

“Not really.”

“Me neither,” she said. “Life is horrible enough.” The clip in her hair was slipping. She reached up and pulled it free, then twisted her hair into a rope and pinned it back again. “When I was a kid, my grade went on this field trip to SeaWorld in Geauga Lake. And you know how they have the killer whale shows, right?” He nodded. “So we’re all there, every second grader in school, and we’re all laughing and cheering and having a great time and then—” One of her hands shot across her body, grabbed the other wrist, and yanked it down, like a crocodile taking down a gazelle. “Bam. The whale grabs the trainer by the leg and pulls her right down to the bottom of the pool.”

Patrick stared at her. “It killed her?”

“No. It let her go and she crawled up onto the deck. Smiling, can you believe it? She’d just been munched by a killer whale in freaking Ohio and she had to smile because it was her job. We just thought we’d get to see some neat animals, maybe pet a sea urchin in the tide pool, and then suddenly it’s all Wild Kingdom.”

“That’s why I like horror movies,” he said. “Every night I wake up and go to work and come home and go to sleep and wake up and go to work and come home and go to sleep. A couple of showers, some pizza, the occasional autoerotic incident—”

“Don’t tell me that.”

“We keep getting eaten by the whale, is my point. Day after day, and day after day we have to smile about it.”

“Patrick, Patrick, Patrick. Sometimes I’m sad for you.” Her face belied her words, though. She understood exactly what he meant. He could see it in her eyes.

“But most of the time you love me,” he said.

“Some of the time,” she said. “Some of the time, if you’re lucky, you grim bastard.”

Soon, they said good night, and went to bed. Not long afterward, Patrick, who was semi-awake and restless, heard a tap at his door. Caro didn’t wait for him to answer. She came in and closed the door behind her. Her hair was down loose around her shoulders again and in the moonlight it didn’t look like cola, it looked like ink.

Half-convinced that he’d fallen asleep after all, he moved over on the bed, and she lay down next to him. She brought her knees up so that her shins pressed against his side. They didn’t talk. The silence was a membrane between them, thick and organic.

When he put his arm around her it felt like something they had done before. When he kissed her it felt like he was crawling inside her, down her throat and into her chest, where there was a warm quiet place that was safe and private and only his. She put a hand on his stomach, under his shirt. He tasted salt on her face but her neck was sweet and mild under his tongue and when he closed his eyes and touched her, the world slipped away and it didn’t matter what he did, it didn’t matter what they did. So they did it all.

He awoke to find her sitting on the edge of the bed, not looking at him. The sky was lighter than it had been and he must have been holding her because his arms felt conspicuously empty. The place on his chest where she’d been sleeping seemed to ache.

He reached for her. She stopped his arm in midair. “Don’t.”

Confused, not fully conscious, he sat up. Put his hands on her shoulders.

She jumped as if he’d burned her. “Jesus. Leave me alone. Can’t you just leave me alone?”

Then she was gone, and if not for the inexorable oh-fuck-what-have-I-done ringing through his brain, he would have thought he’d dreamed it all.

TWO

Once, when Verna Elshere and her sister were children, their father took them to a place in Janesville where someone he knew was erecting a church. He showed them piles of waiting materials: huge sheets of glass, rolls of pink insulation, shining aluminum ductwork. After the church was built they attended the consecration. In the sleek lobby, redolent of paint and new carpeting, Dad reminded the girls that everything they saw had been built by man, not God. They’d seen the building half-formed, he said, so they knew what he said was true. The building was nothing but a clever assemblage of goods. It was the spirit that made the place holy, and the spirit was in the people, and that was why he held his worship meetings in their basement, and not in a church.

Ratchetsburg High School, too, was nothing but a building. The doors were only doors, and behind them were only hallways and classrooms and lockers and drinking fountains, all of it—every hinge, every rivet—built by man. There was nothing permanent, nothing that could not be thrown down. Nothing to be afraid of.

“Hey,” the boy behind her whispered. “Hey, Elshere.”

She didn’t want to turn around, but she had to. You always had to turn around.

This was only the first day, but the two boys sitting at the table behind hers in the biology lab clearly knew each other well. They were handsome and healthy-looking, with clear skin and muscular arms. The one on the left, the one who’d tapped her shoulder, had nearly black hair and striking blue eyes. At the table with them sat a girl with the kind of face that came preinserted in picture frames, her gorgeous red hair styled like that of a movie star from a grocery store checkout magazine. Verna wondered if there was any chance that she could change seats, or schools, or selves.

The striking boy gave her a dazzling smile. “What kind of freak are you?” he whispered.

His voice was loud enough for everyone around them to hear, but quiet enough to blend into the general murmur. At the front of the room, Mr. Guarda was working his way through the class roster. Verna didn’t want to answer, but she had to. You always had to answer.

“What are you talking about?” she whispered back, trying to sound contemptuous.

The boy’s lovely smile broadened. “I said, what kind of freak are you? Are you a Jesus freak, like your sister used to be, or are you a vampire freak, like she is now?” His blue eyes were sparkling, his voice friendly and musical. “Or are you some new kind of Elshere freak we haven’t heard of yet?”

In the open collar of the boy’s shirt, Verna saw a gold saint medallion on a chain. Verna’s father said Catholics prayed to saints because they didn’t trust God. She wondered if there was a patron saint of torturers.

“What was your name again?” he said. “Venereal?”

The redhead giggled. Grinning, the less remarkable-looking boy said, “Venereal Elshere. She’s a sex freak.”

Verna’s arms and legs felt very heavy. She turned around.

Mr. Guarda passed out the textbooks. The covers were new and bright, but the spines were uniformly broken. Instead of sitting stable and strong, they slumped to one side.

The redhead raised her hand. “Yes, Calleigh?” Mr. Guarda said.

“Somebody cut out a hunk of my book, Mr. Guarda.” Her voice was cool as cream.

“I’m aware of that. We’ve decided not to teach that chapter in this school district.” Did Mr. Guarda’s eyes flicker toward Verna, or did she imagine it?

“Why not?”

“Would you like me to write you a pass to the principal’s office so Mr. Serhienko can explain it to you?”

“Why don’t we ask Verna Elshere to explain it to us?” Calleigh said.

The class made gleeful oooooh