Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

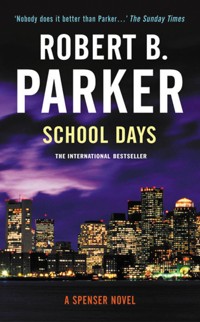

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Spenser Novel

- Sprache: Englisch

A troubled teenager accused of a horrific crime draws Spenser into one of the most desperate cases of his career Lily Ellsworth - erect, firm, white-haired and stylish - is the grand dame of Dowling, Massachusetts, and possesses an iron will and a bottomless purse. When she hires Spenser to investigate her grandson Jared Clark's alleged involvement in a school shooting, Spenser is led into an investigation that grows more harrowing at every turn. Though seven people were killed in cold blood, and despite being named as a co-conspirator by the other shooter, Mrs. Ellsworth is convinced of her grandson's innocence. Jared's parents are resigned to his fate, and the boy himself doesn't seem to care whether he goes to prison for a crime he might not have committed. As the probe goes on, Spenser finds himself up against a number of roadblocks - from the school officials who don't want him investigating, to Jared's own parents, who are completely indifferent to the boy's defence. Ultimately Spenser discovers a web of blackmail and some heavy-duty indiscretions-and a truth too disturbing to contemplate. Before the case reaches its unfortunate end, Spenser is forced to make a series of difficult decisions-with fatal consequences.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 268

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Two students in ski masks execute seven people at Dowling Academy before one of them, Wendell Grant, surrenders to police. The authorities are convinced the other perpetrator was Jared Clark. Clark’s grandmother Lily Ellsworth is the grand dame of Dowling, Massachusetts, and possesses an iron will and bottomless purse. When she hires Spenser to investigate her grandson’s alleged involvement in the school shooting, the P.I. is led into an investigation that grows more harrowing at every turn: the boy himself seems indifferent to his own fate, and the school officials don’t want the detective on the case. But as he digs further Spenser uncovers a web of blackmail and some heavy-duty indiscretions, and, before the case reaches its unfortunate end, a truth too disturbing to contemplate …

Robert B. Parker (1932-2010) has long been acknowledged as the dean of American crime fiction. His novels featuring the wise-cracking, street-smart Boston private-eye Spenser earned him a devoted following and reams of critical acclaim, typified by R.W.B. Lewis’ comment, ‘We are witnessing one of the great series in the history of the American detective story’(The New York Times Book Review).

Born and raised in Massachusetts, Parker attended Colby College in Maine, served with the Army in Korea, and then completed a Ph.D. in English at Boston University. He married his wife Joan in 1956; they raised two sons, David and Daniel. Together the Parkers founded Pearl Productions, a Boston-based independent film company named after their short-haired pointer, Pearl, who has also been featured in many of Parker’s novels.

Robert B. Parker died in 2010 at the age of 77.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR ROBERT B. PARKER

‘Parker writes old-time, stripped-to-the-bone, hard-boiled school of Chandler… His novels are funny, smart and highly entertaining… There’s no writer I’d rather take on an aeroplane’ – Sunday Telegraph

‘Parker packs more meaning into a whispered “yeah” than most writers can pack into a page’ – Sunday Times

‘Why Robert Parker’s not better known in Britain is a mystery. His best series featuring Boston-based PI Spenser is a triumph of style and substance’ – Daily Mirror

‘Robert B. Parker is one of the greats of the American hard-boiled genre’ – Guardian

‘Nobody does it better than Parker…’ – Sunday Times

‘Parker’s sentences flow with as much wit, grace and assurance as ever, and Stone is a complex and consistently interesting new protagonist’ – Newsday

‘If Robert B. Parker doesn’t blow it, in the new series he set up in Night Passage and continues with Trouble in Paradise, he could go places and take the kind of risks that wouldn’t be seemly in his popular Spenser stories’ – Marilyn Stasio, New York Times

THE SPENSER NOVELS

The Godwulf Manuscript

Chance

God Save the Child

Small Vices*

Mortal Stakes

Sudden Mischief*

Promised Land

Hush Money*

The Judas Goat

Hugger Mugger*

Looking for Rachel Wallace

Potshot*

Early Autumn

Widow’s Walk*

A Savage Place

Back Story*

Ceremony

Bad Business*

The Widening Gyre

Cold Service*

Valediction

School Days*

A Catskill Eagle

Dream Girl (aka Hundred-Dollar Baby)*

Taming a Sea-Horse

Pale Kings and Princes

Now & Then*

Crimson Joy

Rough Weather

Playmates

The Professional

Stardust

Painted Ladies

Pastime

Sixkill

Double Deuce

Lullaby (by Ace Atkins)

Paper Doll

Wonderland (by Ace Atkins)*

Walking Shadow

Silent Night (by Helen Brann)*

Thin Air

THE JESSE STONE MYSTERIES

Night Passage*

Night and Day

Trouble in Paradise*

Split Image

Death in Paradise*

Fool Me Twice (by Michael Brandman)

Stone Cold*

Killing the Blues (by Michael Brandman)

Sea Change*

High Profile*

Damned If You Do (by Michael Brandman)*

Stranger in Paradise

THE SUNNY RANDALL MYSTERIES

Family Honor*

Melancholy Baby*

Perish Twice*

Blue Screen*

Shrink Rap*

Spare Change*

ALSO BY ROBERT B PARKER

Training with Weights

A Year at the Races (with Joan Parker)

(with John R. Marsh)

All Our Yesterdays

Three Weeks in Spring

Gunman’s Rhapsody

(with Joan Parker)

Double Play*

Wilderness

Appaloosa

Love and Glory

Resolution

Poodle Springs

Brimstone

(and Raymond Chandler)

Blue Eyed Devil

Perchance to Dream

Ironhorse (by Robert Knott)

*Available from No Exit Press

FOR JOAN: hasn’t it been one hell of a ride to Dover

1

Susan was at a shrink conference in Durham, North Carolina, giving a paper on psychotherapy, so I had Pearl. She was sleeping comfortably on the couch in my office, which had been put there largely for that purpose, when a good-looking elderly woman came in carrying a large album of some kind and disturbed her. Pearl jumped off the couch, stood next to me, dropped her head, and growled sotto voce. The woman looked at her.

‘What kind of dog is that?’ she said.

‘A German shorthaired pointer,’ I said.

‘Aren’t they brown and white?’

‘Not always,’ I said.

‘What’s her name?’

‘Pearl.’

‘Hello, Pearl,’ the woman said, and walked to my client chair and sat down. Pearl left my side, went and sniffed carefully at the woman’s knees. The woman patted Pearl’s head a couple of times. Pearl wagged her tail slightly and went back to the couch. The woman put her large album on my desk.

‘I have kept this scrapbook,’ the woman said to me, ‘since the day my grandson was arrested.’

‘Hobbies are nice,’ I said.

‘It is far more than a hobby, young man,’ the woman said. ‘It is the complete record of everything that has happened.’

‘That might prove useful,’ I said.

‘I should hope so,’ the woman said.

She placed it on my desk. ‘I wish you to study it.’

I nodded.

‘Will you leave it with me?’ I said.

‘It is yours,’ she said. ‘I have another copy for myself.’

The woman’s name was Lily Ellsworth. She was erect, firm, white-haired, and stylish. Too old for me, at the moment, but I hoped Susan would look as good as Mrs. Ellsworth when we got to that age. Being as rich would also be pleasant.

‘And after I’ve studied it, ma’am,’ I said, ‘what would you like me to do?’

‘Demonstrate that my grandson is innocent of the charges against him.’

‘What if he’s not?’ I said.

‘He is innocent,’ she said. ‘I will entertain no other possibility.’

‘What I know of the case, he was charged along with another boy,’ I said.

‘I have no preconceptions about the other boy,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said. ‘His guilt or innocence is of no consequence to me. But Jared is innocent.’

‘How’d you happen to come to me?’ I said.

‘Our family has been represented for years by Cone, Oakes,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said. ‘I asked our personal attorney to get me a recommendation. He consulted with their criminal defense group, and you were recommended.’

‘Do they represent your grandson?’ I said.

‘No. His parents have insisted on hiring an attorney of their own.’

‘Too bad,’ I said. ‘Cone, Oakes has the best defense lawyer in the state.’

‘If you take this case and need to consult him,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said, ‘you may list his fee as an expense.’

‘Her,’ I said.

Mrs. Ellsworth nodded gravely and didn’t comment.

‘Do you know who they have hired?’ I said.

‘His name is Richard Leeland. He is my son-in-law’s fraternity brother.’

‘Oh,’ I said.

‘You don’t know of him?’ Mrs. Ellsworth said.

‘No, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t good.’

‘Perhaps not,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said. ‘But being Ron’s fraternity mate is not in itself much of a recommendation.’

‘Ron being your son-in-law,’ I said.

‘Ron Clark,’ she said. ‘I still remember, approximately, a passage in The Naked and the Dead where someone describes a man as “Westchester County, Cornell, a DKE, and a perfect asshole.” Mailer could have been writing of my son-in-law. Except that Ron grew up in Greenwich and went to Yale.’

‘A man can overcome his beginnings,’ I said.

‘I wonder if you have,’ she said. ‘You seem a bit sporty to me.’

‘Sporty?’ I said.

‘A wisenheimer.’

‘Wow,’ I said. ‘It’s been years since someone called me a wisenheimer.’

‘I may not be current in my slang,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said. ‘But I know people. You are a wisenheimer.’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I am.’

‘But not just a wisenheimer,’ she said.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I have other virtues.’

‘What are they?’ she said.

‘I am persistent, and fearless, and reasonably smart.’

‘And modest,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said.

‘That too,’ I said.

‘If I hire you for this, will you put Jared’s interests above all else?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I put Susan Silverman’s interests above all else.’

‘Your inamorata?’

‘Uh-huh.’

‘That’s as it should be,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said. ‘Any other problems I should be alert to?’

‘I don’t take direction well,’ I said.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I don’t, either.’

‘And,’ I said, ‘you have to understand that if your grandson is guilty, I won’t prove him innocent.’

‘He is not guilty,’ Mrs. Ellsworth said.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘I’ll do what I can.’

2

I stood at my window on the second floor and watched Mrs. Ellsworth as she came out of my building and rounded the corner, walking like a young woman. Pearl got off the couch and came over and looked out the window with me. She liked to do that. Mrs. Ellsworth got into a chauffeur-driven Bentley at the corner of Berkeley and Boylston.

‘She can afford me,’ I said to Pearl.

Late summer was in full force in the Back Bay. But, August or not, it was gray and showery, and quite cool, though not actually cold. Most of the young businesswomen were coatless under their umbrellas. I watched as the Bentley, gleaming wetly, pulled away from the curb and turned right onto Boylston. The driver would probably turn right again at Arlington, and then go up St. James Ave to the Pike and on to the western suburbs, with his wipers on an interval setting. I watched for a bit longer as two young women in bright summer dresses, pressed together under a big golf umbrella, crossed Boylston Street toward Louie’s. Summer dresses are good.

When they had crossed, I turned back to my desk and sat down and picked up Mrs. Ellsworth’s scrapbook. Neatly taped on the cover, an engraved calling card read “Lily Ellsworth,” with an address in Dowling. I opened the scrapbook and began to read. Pearl went back to the couch. She liked to do that, too.

Two seventeen-year-old boys wearing ski masks had walked into the Dowling School, a private academy they both attended, and opened fire, each with a pair of nine-millimeter handguns. Five students, an assistant dean, and a Spanish teacher were killed. Six more students and two other teachers were wounded before the Dowling cops arrived, and the kids had barricaded themselves in the school library with hostages. The Dowling Police kept them there until a State Police hostage negotiator arrived with a State Police SWAT team standing by. Negotiations took six hours, but at three in the afternoon, one of the boys took off his ski mask and swaggered out, hands in the air, smirking at the cameras. The other one had disappeared.

The captured boy was named Wendell Grant. After two days of questioning, he finally gave up his buddy, Jared Clark. Clark denied his participation but had no alibi for the time, and was known to hang with Grant. After a few days in jail, Clark confessed. There was much more. Newspaper stories, transcripts of television and radio newscasts. Copies of police reports and forensic data; pictures of the boys. Neither was unusual-looking. Profiles of victims, interviews with survivors, and bereaved relatives. It didn’t offer me much that was useful at the moment, though it would be a good source for names and dates later. And I didn’t expect it to be a good source of facts, now or later.

When I got through reading the scrapbook, I called Rita Fiore.

‘What do you know about a defense attorney named Richard Leeland?’ I said.

‘Never heard of him,’ Rita said.

‘He’s counsel for one of the kids who shot up the school in Dowling,’ I said.

‘That kid shouldn’t have a defense counsel I never heard of,’ Rita said. ‘But, I gather, at least he has you.’

‘His grandmother took your recommendation.’

‘Ah,’ Rita said. ‘That’s who was asking. Everyone was so fucking discreet, I didn’t know who the client was. How come they didn’t hire me to help you or, actually, hire you to help me after they hired me?’

‘Leeland was the kid’s father’s frat brother at Yale.’

‘Oh, God,’ Rita said.

‘I know,’ I said. ‘Can you find out if he’s any good?’

‘Sure. I’ll call the DA’s office out there. What’s in it for me?’

‘Dinner?’ I said.

‘At my house?’

‘Sure. You get a date, I’ll bring Susan, it’ll be swell.’

‘You smarmy bastard,’ Rita said.

‘You can’t get a date?’ I said.

‘I had other plans,’ Rita said.

‘I thought you were seeing that police chief from the North Shore,’ I said.

‘I was,’ Rita said. ‘But he loves his ex-wife. You. Him. Every winner I find is in love with somebody else.’

‘Maybe that’s not an accident,’ I said.

‘Fuck you, Sigmund,’ Rita said.

‘Or not,’ I said. ‘Susan’s in North Carolina. I’ll buy you dinner at Excelsior.’

‘How easily I settle,’ Rita said. ‘I’ll meet you there at seven.’

‘Have your secretary make us a reservation,’ I said.

‘My secretary?’

‘I don’t have one,’ I said.

3

Dowling is west of Boston. High-priced country with a village store and a green, and a lot of big shade trees that arch over the streets. As I drove along the main street, I passed a young girl with long blond hair and breeches and high boots, riding a bay mare along the side of the street, and eating an ice cream cone. It might have been pistachio. I pulled into the little lot in front of the village store and parked beside an unmarked State Police car and went in. There was a counter and display case opposite the door, and a few tables. In the back of the store were shelves, and along two sides were glass-front freezers. Two women in hats were at one table with coffee. A young couple who looked like J. Crew models were having ice cream at another table. Alone at a third table was a stubby little guy with thick hands and thick glasses, wearing a tan poplin suit and a light-blue tie. I took a wild stab.

‘Sergeant DiBella?’ I said.

He nodded. I sat down across from him at the table.

‘Healy called me,’ he said. ‘I used to work for him.’

There were a few crumbs on a paper plate in front of DiBella.

‘Pie,’ I said.

‘Strawberry rhubarb. Counter girl told me they make it themselves.’

‘I better have some,’ I said. ‘Don’t want to offend them.’

‘Make it two,’ DiBella said.

The pie was all it should have been. DiBella ate his second piece just as if he hadn’t eaten a first one. We both had coffee.

‘I’ve read the press accounts,’ I said, ‘of the school shooting.’

‘They’re always on the money,’ DiBella said.

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘I just wanted to test you against them.’

A couple of local girls came in wearing cropped T-shirts and low-slung shorts, showing a lot of postpubescent abdomen. We watched them buy some sort of iced coffee drinks.

‘Be glad when that fad is over,’ DiBella said.

‘I’ll say.’

‘You got kids?’ DiBella said.

‘No.’

‘I got two daughters,’ he said.

‘So you’ll be really glad,’ I said.

The girls left.

‘Healy says the Clark kid’s grandmother hired you to get him off.’

‘I like to think of it as establish his innocence,’ I said.

DiBella shrugged.

‘Grant fingered him,’ DiBella said. ‘He confessed. You got some heavy sledding.’

‘But nobody actually saw him in the school,’ I said.

‘He was wearing the ski mask.’

‘So you only have Grant’s word.’

DiBella grinned. ‘And his,’ DiBella said. ‘’Course, he could be a lying sack of shit.’

I nodded.

‘Where’d they get the weapons?’

DiBella shook his head. ‘Don’t know,’ he said.

‘Not family weapons?’

‘Nope, far as we can tell, neither family kept weapons.’

‘So two seventeen-year-old kids in the deepest dark center of exurbia come up with four nines,’ I said.

‘And extra magazines,’ DiBella said.

‘Loaded?’ I said.

‘Yep.’

‘All the same guns?’

‘No,’ DiBella said. ‘A Browning, a Colt, two Glocks.’

‘Same ammo,’ I said. ‘Different magazines.’

DiBella nodded.

‘The magazines and the guns were color-coded with Magic Marker,’ he said.

‘Sounds like a plan,’ I said.

‘Yeah. The thing is, they planned how to do it pretty good. But they didn’t seem to have any plan for afterwards.’

‘You mean to get away,’ I said.

DiBella nodded.

‘They explain that?’ I said.

DiBella smiled. ‘They don’t explain shit,’ he said. ‘All they say is we done it, you don’t need to know why.’

‘Or how the second kid got away with the cops around the building?’

‘My guess? He took off his mask and ditched his guns and ran out with the other kids early in the proceedings.’

‘Must have been a Chinese fire drill,’ I said.

‘Especially before our guys showed up. When it was just the local cops.’

‘Did you get there?’

DiBella nodded.

‘Me, everybody. I came in with the negotiation team. SWAT guys were already there. The bomb squad showed up a little after me. There were two or three local departments on the scene. Nobody in overall charge. One department didn’t want to take orders from another department. None of them wanted to take orders from us. Took a while for the SWAT commander to get control of the thing. And when he did, we still didn’t know who was in there, or how many. We didn’t know if the place was rigged. We didn’t know if they had hostages, or how many. We’d have shot somebody if we knew who to shoot. Kids were jumping out windows and running out fire doors.’

‘Who went in?’

‘Hostage negotiator. Guy named Gabe Leonard. Everybody was milling around, trying to figure how to get in touch inside, and the bomb-squad guys were trying to figure how to tell if the place was rigged. I was trying to get a coherent story from anybody, a student or teacher who’d been inside and was now outside, and Gabe says, “fuck this,” and puts on a vest and walks in the front door.’

‘And nothing blew up,’ I said.

‘Nothing,’ DiBella said.

We were out of coffee. I got up and got us two more cups.

‘Gabe walks through the place, which is empty, like he’s walking on hummingbird eggs. There’s nobody else in there except the bodies, and finally the kid, in the president’s office, with the door locked. They establish contact through the locked door and Gabe eventually gets the kid to answer the phone. Kid says he will, and Gabe calls out to us and one of the hostage guys calls the number and patches Gabe in, and they’re in business. Gabe, and the kid, and us listening in.’

‘How’d he get him out?’ I said.

‘I’ll get you a transcript, but basically, he said, “Be a standup guy. Whatever you were trying to prove, you need to finish it off by walking out straight up, not have us come in and drag out your corpse.”’

‘And the kid says, “You’re right,” and he opens the door and comes out,’ DiBella said. ‘Takes off his ski mask. Gabe takes his guns, and they walk out together. Gabe said he wouldn’t cuff him, and he didn’t.’

‘Until he got outside,’ I said.

‘Oh, sure, then the SWAT guys swarmed him and off he went.’

‘Film at eleven,’ I said.

‘A lot of it,’ DiBella said.

4

The Dowling School was on the western end of town, among a lot of tall pine trees. I drove between the big brick pillars, under the wrought-iron arch, up the curving cobble-stone drive, and parked in front, by a sign that said faculty only. There was one other car in front, a late-model Buick sedan.

The place had the deserted quality that schools have when they’re not in session. The main building had a stone façade with towers at either end and a crenellated roofline between them. The front door was appropriate to the neo-castle style, high and made of oak planking with big wrought-iron strap hinges and an impressive iron handle. It was locked. I located a doorbell and rang it. There was silence for a long time, until finally the door opened and a woman appeared.

‘Hello,’ she said.

‘My name is Spenser,’ I said. ‘I’m working on the shooting case and wondered if I might come in and look around.’

‘Are you a policeman?’ the woman said.

‘I’m a private detective,’ I said. ‘Jared Clark’s grandmother hired me.’

‘May I see some identification?’

‘Sure.’

I showed her some. She read it carefully, and returned it.

‘My name is Sue Biegler,’ she said. ‘I am the Dean of Students.’

‘How nice for you,’ I said.

‘And the students,’ she said.

I smiled. One point for Dean Biegler.

‘What is it you wish to see?’ she said.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. ‘I just need to walk around, feel the place a little, see what everything looks like.’

Dean Biegler stood in the doorway for a moment.

‘Well,’ she said.

I waited.

‘Well, I really don’t have anyone to show you around,’ she said.

‘That’s a good thing,’ I said. ‘I like to walk around alone, take my time, see what it feels like. I won’t steal any exam booklets.’

She smiled.

‘You sound positively impressionistic,’ she said.

‘Impressively so,’ I said.

She smiled again and sighed.

‘Come in,’ she said. ‘Help yourself. If you need something, my office is here down this corridor.’

‘Thank you.’

Inside, it smelled like a school. It was air-conditioned and clean, but the smell of school was adamant. I never knew what the smell was. Youth? Chalk dust? Industrial cleaner? Boredom?

I had seen enough diagrams of the school and the action in the newspapers to know my way around. There were four offices, including Dean Biegler’s, opening off the central lobby. The rest of the school occupied two floors in each of two wings that ran left and right out of the lobby. The school gym was behind the rest of the school, connected by a narrow corridor, and beyond the gym were the athletic fields. There was a cafeteria in the basement of the school, along with rest rooms and the custodial facilities. A library was at the far end of the left wing. Stairs went to the second floor in stairwells on each side of the lobby. On the second floor above the lobby were the teachers’ lounge and the guidance offices. I began to stroll.

They had come in the front door, apparently, and past the offices in the lobby and turned left down the long corridor that ended at the library. Each was wearing a ski mask. Each was carrying two guns. Each had a backpack with extra ammunition in magazines, color-coded to the guns they had. They shot the first teacher they encountered, a young woman named Ruth Cort who had no class that period, and who had probably been on her way from the teachers’ lounge upstairs to the library. She had bullets from two different guns in her. But there was no way to say if she had been shot by one shooter with two guns, or two shooters, one gun each. In fact, they had never been able to establish who shot whom. The guns and the backpacks were simply left on a table in the library when Grant came out, and no one could identify which had been used by whom. The cops had tried backtracking, establishing who had what color coding on which gun, but the eyewitnesses gave all possible versions, and it proved fruitless. There was powder residue on two coveralls that the shooters had discarded in the library, but none on their hands, because they wore gloves. The gloves, too, were discarded, and there was no way to establish which pair belonged to whom. Both had powder residue on them.

The Norman Keep conceit ended in the lobby. The cinderblock corridor was painted two tones of green and lined with lockers, punctuated by gray metal classroom doors. I went into the first classroom. The walls were plasterboard painted like the corridor. There was a chalkboard, windows, chairs with writing arms. A teacher’s table up front with a lectern on it. Chalk in the tray at the bottom of the chalkboard. A big, round electric clock on the wall above the door. It had the personality of a holding pen.

I could taste the stiflement, the limitation, the deadly boredom, the elephantine plod of the clock as it ground through the day. I could remember looking through windows like these at the world of the living outside the school. People actually going about freely. I tried to remember what Henry Adams had written. ‘A teacher is a man employed to tell lies to little boys’? Something like that. I wondered if anyone had lied to little girls in those days.

I moved on down the corridor, following the route of the shooters. I was wearing loafers with leather heels. I could hear my own footsteps ringing in the hard, empty space. The shooters hadn’t made it to the second floor. The first Dowling cops had shown up about the time the shooters reached the library, and the shooters holed up there. Hostages were facedown on the floor, including the school librarian, a woman of fifty-seven, and a male math teacher who had been in there reading The New York Times. I could almost feel their moment, complete control, everybody doing what they were told, even the teachers. The room was unusual in no way. Reading tables, books, newspapers in a rack, the librarian’s desk up front. Quiet Please. I looked at some of the books: Ivanhoe, Outline of History, Shakespeare: Collected Works, The Red Badge of Courage, Walden, The Catcher in the Rye, Native Son. Nothing dangerous. No bad swearing.

The windows faced west. And the late sun, low enough now to shine nearly straight through the windows, made the languid dust motes glisten with its gaze. I walked to the back of the library, near the big globe that stood in the far corner. I would have stood there, where I could see the door and the windows, holding a loaded gun in either hand, in command. King of the scene.

The library door opened as I stood looking at the room, and two Dowling cops walked in. They were young. One was bigger. They were both wearing straw Smokey the Bear hats. Summer-issue.

‘What exactly are you doing here?’ the bigger one said.

‘Reliving school days,’ I said.

‘Excuse me?’

‘School days,’ I said. ‘You know. Dear old golden-rule days.’

They both frowned.

‘Chief wants us to bring you over to the station,’ the bigger one said.

The fact that the chief wanted me didn’t mean I had to go. But I thought it would be in my best interest to cooperate with the local cops, at least until it wasn’t.

‘I’ve got my car,’ I said. ‘I’ll follow you down.’

5

The Dowling police station looked like a rambling, white-shingled Cape. The Dowling police chief looked like a Methodist minister I had known once in Laramie, when I was a little kid. He was tall and thin with a gray crew cut and a close-cropped gray moustache. His glasses were rimless. He wore a white shirt with short sleeves and epaulets and some sort of crest pinned to each epaulet. The shirt was pressed with military creases. His chief’s badge was large and gold. His black gun belt was off, folded neatly and lying on the side table near his desk. His gun was in the holster, a big-caliber pearl-handled revolver.

‘I’m Cromwell,’ he said. ‘Chief of Police.’

‘Spenser,’ I said.

‘I know your name,’ Cromwell said. ‘Sit down.’

I sat.

‘Real tragedy,’ Cromwell said, ‘what happened over at that school.’

I nodded.

‘We got there as soon as we heard, contained it, waited for backup and cooperated in the apprehension of the perpetrators,’ Cromwell said.

I nodded.

‘You ever been a police officer, Spenser?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then you know how it goes. You do the job, and the press looks for some way to make you look bad.’

I waited.

‘We got some bad press. It came from people who do not know anything at all about policework. But it has stung my department, and, to be honest with you, it has stung me.’

I nodded.

‘We played it by the book,’ Cromwell said. ‘Straight down the line. By the book. And, by God, we kept a tragedy from turning into a holocaust.’

‘Should I be taking notes?’ I said.

Cromwell leaned back in his chair and looked at me hard. He pointed a finger at me, and jabbed it in my direction a couple of times.

‘Now that was a wiseassed remark,’ Cromwell said. ‘And you might as well know it right up front. We have zero tolerance for wiseasses around here.’

I liked the we. I wondered if it was the royal we, as in we are not amused. On the other hand, it still seemed in my best interest to get along with the local cops. I looked contrite.

‘I’ll try to do better,’ I said.

‘Be a good idea,’ Cromwell said. ‘Now what we don’t need is somebody coming along and poking around and riling everybody up again.’

I was back to nodding again. Cromwell liked nodding.

‘So, who hired you?’ Cromwell said.

I thought about that for a moment. On the one hand, there was no special reason not to tell him. Healy knew. DiBella already knew. On the other hand, it didn’t do my career any good to spill my client’s name to every cop who asked. Besides, he was annoying me. I shook my head.

‘You’re not a lawyer,’ Cromwell said. ‘You have no privilege.’

‘When I’m employed by an attorney on behalf of a client, there is some extension of privilege,’ I said.

‘Who’s the lawyer?’ Cromwell said.

‘I’m not employed by a lawyer,’ I said.

‘Than what the hell are you talking about?’ Cromwell said.

‘I rarely know,’ I said.

I smiled my winning smile.

‘What’s our policy on wiseasses around here?’ Cromwell said.

‘Zero tolerance,’ I said. ‘Except for me.’

Cromwell didn’t say anything for a time. He folded his arms across his narrow chest and looked at me with his dead-eyed cop look. I waited.

Finally, he said, ‘Let me make this as clear and as simple as I can. We don’t want you around here, nosing into a case that is already closed.’

I nodded.

‘And we are prepared to make it very unpleasant for you if you persist.’

I nodded.

‘You have anything to say to that?’ Cromwell said.

‘How about, Great Caesar’s Ghost!’ I said.

Cromwell kept the dead-eyed stare on me.

‘Or maybe just an audible swallow,’ I said.

Cromwell kept the stare.

‘A little pallor?’ I said.

Cromwell stared at me some more.

‘Get the hell out of here,’ Cromwell said finally.

I stood.

‘You must have screwed this up pretty bad,’ I said.

‘If you’re smart, you son of a bitch,’ Cromwell said, ‘you won’t be back.’

‘I never claimed smart,’ I said, and walked out the door.

At least he didn’t shoot me.

6

Fresh from my triumph with the Chief of Police, I thought I might as well go and charm the kid’s lawyer, too.