Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

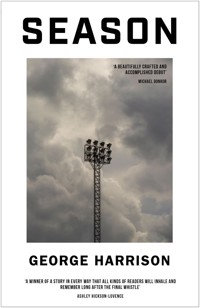

'A beautiful novel about the beautiful game' Jonathan Pearce For ten months of the year, two men are drawn to adjacent seats in a stadium, carrying the burdens of life and pouring all their hopes into their beloved but ailing team. Fatherless and fretful, the Young Man is trying to nurture a precarious new relationship and to find his place in the world. The Old Man, an increasingly isolated carer for his fading wife, knows he has little left to look forward to. Neither fan is a comfortable talker. However, in a slow-motion play of nods, silences and guarded chats, they strike up a tentative friendship across the generational gap. Told through thirty-eight chapters – one for each game of the Premier League campaign – Season is a lyrical, hypnotic and gently uplifting study of loneliness and modern masculinity. About much more than football, it celebrates the healing, unifying and maddening role of ritualised sport in the lives of ordinary people.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 349

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Season

‘We all start out as fans, and whatever our football journey, it remains the crux of all we do. To be reminded so movingly of the power of supporting – both our teams and each other – is a treat. A beautiful novel about the beautiful game’

Jonathan Pearce

‘A beautifully crafted and accomplished debut – an emotionally rich and formally fresh examination of masculinity and alienation that deserves a wide readership’

Michael Donkor, author of Hold

‘A highly accomplished novel written with gut-wrenching, net-busting depth. It effortlessly captures the touching intergenerational bond of two loyal football supporters. Every word counts; everything means something. This is so much more than a novel for fans of the so-called ‘beautiful game’; this is a winner of a story in every way that all kinds of readers will inhale and remember long after the final whistle. I loved it’

Ashley Hickson-Lovence, author of Your Show

‘The world of professional football is usually a graveyard of literary aspiration, but Harrison has found a way of using the match-day experience as a prism through which to examine the lives of the people watching on from the stands. Well observed, neatly handled and full of good things’

D.J. Taylor

‘An absorbing, beautifully written, constantly surprising novel. The description of events on the field, as the side battles relegation, is riveting and completely authentic – but what goes on in the minds of the two men is just as compelling. The insecurities of youth and the frailties of older age are expertly explored. Ultimately it is football’s ability to provide a sense of purpose and belonging to very different people’s lives that makes this a most heartwarming read’

Roger Hermiston, author of Clough and Revie

‘This is a tale familiar to the many of us who enter into maddening relationships with our football club. But it is far more than that – it is about the relationships we strike with others who share the affliction. It is told beautifully and poignantly by the author’

Riath Al-Samarrai, chief sports feature writer, Daily Mail

‘Harrison skilfully evokes the unique and valuable role football plays in so many lives. He captures how moments of sporting euphoria and heartbreak can briefly but beautifully blot out relationship, family and work fears, and the depths of anxiety, gratitude and delight that exist beyond male inarticulacy. A brilliant, original and necessary novel’

Nicolas Padamsee, author of England is Mine

‘Season perfectly captures the comforting rituals of football for taciturn males, old and young. Ambitions are thwarted, lives are lonely, the centre forward fails to hold it up. Yet there’s always the hope that a millionaire in yellow might produce something unexpected in the box to avert the threat of relegation. It’s an unexpected three points away from home for Harrison’

Pete May, author of Massive: The Miracle of Prague

‘A football novel like no other, Season is a love story – not romantic love, but love of team, of game. It’s a love that grabs you young and can never be shaken…for better or for worse’

Guy Swindells, TalkSport

Published in 2025

by Lightning

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

ISBN: 9781785634147

Copyright © George Harrison 2025

Cover design by Ifan Bates and Emily Dinsmore

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro and Bebas Neue

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

For Emily

Contents

Season TicketAway DaySimulationHard ShoulderIts Own Kind of LoveNorwegian WinterSix-PointerThe CastleUnseasonalOffsideUnsettledThe Things They Will ForgiveSnowThe LessonThe Jets and What They MeantOtherwise EngagedStill TimeAllowancesMother Tongue#Vamos!Fine Without YouIn His TimeTeam SheetsAscensionThe RiverAfter HerMemoryMiles AwayFaithThe Run-InOptimismRealismTo Stop Them Being ThrownAgainst the Run of PlayJust a GameSettings and PrivacyNothing Left in HimThe Long SummerAcknowledgements

Also from Lightning

1

Season Ticket

It was a new season, the first game since the last game, and the ground was busy well before kick-off. The Old Man arrived first, and he looked about for familiar faces as he shuffled crablike down the narrow aisle, double-checking the numbers daubed on seatbacks against the number on his printed ticket. Pop music came overloud from the speakers, pushing against the low hum of male chatter. The terrace was already filling up, and one or two men offered the Old Man a nod or some other greeting as a concession to the time they had already spent in one another’s vicinity, years gone past. These were men for whom the rhythms of the year revolved not around meteorological or astrological systems; their days belonged instead to the football calendar, a capricious season all its own.

The Old Man had the same seat as last year, the same seat as always. This was the seat in which he had commiserated when they last went down and celebrated when they went back up, just a few seasons ago. The adjacent seat had been his wife’s. Here, before the summer, they had watched their captain – the Finn, freshly recovered from his latest injury – tap in the goal that would keep them in the league. The Old Man had kissed his wife drily on the cheek as the Finn sprinted across to the dugout, where he was embraced by the manager and his coaching staff and the rest of the players, an unused substitute in a neon bib jumping upon his back. The younger men in the front few rows had surged towards the pitch, and after the game they had broken through the ranks of stewards in a tide of bright colour: garish jerseys flaring in the sun, scarves swinging like knitted flails. The Old Man smiled at the memory, looked to the seat beside his. The seat was folded back, yellow plastic stark against the dull concrete underfoot.

Throughout the previous season, the Old Man’s wife had found it increasingly difficult to get to the ground and climb the steps and fight against the crowds. The stadium was too noisy, the tickets too expensive, and so this season she had resolved to follow the team from home. She had suggested, earlier in the summer, that he might do the same.

And how would I meet people then, he had said, as if he was always meeting people at the ground. What would I do with myself?

At the time, the Old Man had felt a measure of guilt, but it did not last. The football was important to him, now more than ever. So here he was, and there she was, and now the seat beside his was no longer hers.

Nearby, not far from that seat, the Young Man emerged from the concourse. That familiar climb up the steps and then the pitch – the grass impossibly green, the markings crisp and white and beautiful in the sunlight – opening like a huge flower beneath him. It took his breath away, every time. The hum of ambient talk welling all around, the loudness of the music, the stolid permanence of the goal in front of the terrace. Even the glare of the great digital scoreboard seemed like a blessing as it cycled through static adverts for cars and bookmakers and a local construction firm, the stills interspersed with highlights from the previous season. A clip of the Finn dropping into a knee-slide before the corner flag, teammates mobbing him after another late winner.

The Young Man arrived just as the players, the Finn among them, were coming out for their warm-ups. A shout went up from the back of the terrace, and many of the home fans stood. They clapped and cheered, their applause cascading down the steps and drowning out the music. These were the same fans who had viciously, almost gleefully, denigrated their own players for most of the previous season (right until the revival at the end, when the Finn came back – reborn, you might say – to save them). Nobody thought their enthusiastic support for the team, now, was inconsistent. Such was football, and such was the way of football fans.

Today it was the Englishman, their young full-back, who was first out, and he raised a palm to the terrace in acknowledgment of the men gathered there. Then the Finn, looking lean in one of the new training tops, and the Norwegian midfielder who had arrived on loan weeks before, heralded with almost hysterical excitement in the local newspaper. The Norwegian would never live up to his billing, the Old Man knew, but regardless, it was something to see him in the flesh. The Young Man, being less cynical, had fallen for the hype, and he cheered as the Norwegian jogged languidly towards the centre circle. He already believed that the Norwegian would make all the difference this time round. He needed to believe, was what it was.

Soon the players began their warm-ups, and the fans settled once more into their seats, their conversations. The terrace was almost half-full, and more fans emerged from the concourse with every minute. The Young Man, looking for his new seat, moved down the aisle towards the Old Man, who stood and apologised for being in the way. The Young Man squeezed past and stopped at the seat which had been occupied in years before by the Old Man’s wife. The Young Man nodded at the Old Man. It was his seat now.

The two men sat in their narrow seats, legs almost touching, and let the sounds of the stadium fill what little space there was between them. Down below, the goalkeeping coach was shouting instructions to his charges as he lined up a row of balls on the edge of the box. Both men let their gaze fall on the scene: the back-up keeper diving, pushing the coach’s deliberately tame shot around the post. The first-choice keeper, the Dutchman, watched on, clapping his gloved hands in encouragement. The Old Man looked to the sky, which was pure and clean. Just a few clouds, strung in brilliant white threads against the blue.

Nice day for football, the Old Man said. There was a slight rasp to his voice.

The Young Man nodded. Football weather, he said. They’ll be well up for it, a day like today. He looked over to the section of the adjacent stand which was reserved for away fans. They bring good numbers, this lot, he added.

The Old Man made a vague noise of agreement and looked across to where the away fans had started to gather. His eye was drawn to the flag moving in an unfelt breeze above the stand. He watched the flag whip and fall, the club crest contorting against a bold yellow background. It was impossible not to think, in that moment, of games gone by, of aborted cup runs and play-off finals and relegation six-pointers – decades of football and just the one real trophy to show for it. He had seen a lot in his time, the Old Man, and his wife had seen much of it with him. He had not given her much thought when he chose to renew his season ticket and go through it all once more, starting from nothing all over again. But now, for the first time, he realised what it would mean to do it on his own.

Down below, the goalkeeping coach had called in his players for a huddle. One of the fitness coaches was setting out a row of cones along the touchline. Unsupervised for the moment, a group of attacking players had gathered just outside the box, and now the players started taking shots into the empty net. A gull wheeled above the pitch, its shadow like a puppet on the turf.

When the home players were done with their warm-ups, they traipsed in twos and threes to the dugouts and disappeared down the tunnel. By now, the away fans were all in their corral. They were busy at work: some unfurling banners, others singing or taking photographs. When their players made for the tunnel, a fresh chorus started up in the away section. The Young Man looked over at them. The Old Man noticed him looking, but he couldn’t think of anything to say. Then the Young Man asked if he could get past, since there was still time for a pint before kick-off.

The Young Man left the Old Man thinking once more of his wife. She would be turning on the TV around now, the Old Man knew. He could picture her in one of the two reclining chairs in the main room of their apartment, waiting for the games to start. He had sold their house and bought that apartment because he thought it would be freeing. They were nearer the train station now, so it would be easier to go on day trips to the coast. That requirement had seemed so important when they were looking, but they had not left the city once in all the months since they had moved. There were days now when they could not even bring themselves to descend in the lift and walk into town, and on those days they barely left that one room. But today was not one of those days – at least, not for the Old Man. It was something to be grateful for, he supposed.

The Young Man, as he made his way back down the aisle and towards the steps, heading for the concourse, thought also of his home, but only because he could not remember if he had locked the front door. He rented a ground-floor flat near the river, a street with willows draped verdantly across the water. Young people, like him, were to be seen paddle-boarding there on nice days. He lived alone.

The Young Man had to walk all the way through the city to get to the ground, and today two noteworthy occurrences had disturbed him on the walk. The first came as he was crossing the bridge at the end of his street, where a beggar asked him for money. The Young Man said he had no change, and the beggar, noting his jersey and scarf, told him to stop at the bridge on his way back and tell him the score. The second provocation came soon after, on the other side of the city, as the tide of men in yellow jerseys – all walking the same route – was thickening into a throng. That was when the Young Man had noticed a bird dead on the pavement, all opened up like a dropped sandwich. Now, in the concourse, the Young Man thought back to those images – the beggar and the dead bird – as he tasted his pint, and then he thought of the Finn. He hoped the Finn’s ankle would hold throughout the season.

2

Away Day

The Young Man was at the stadium in good time. It was early, and a tentative sun lit the men, mostly, who were milling about beside a phalanx of coaches. The rest of the car park was empty.

The Young Man approached the nearest group and took up a position on the edge of the assembly. Two of the men shuffled to make room for him. A man in a beanie was talking loudly about the Finn – about his ankle, in particular. He said the Finn was becoming injury-prone in his old age, that fragility was a poor trait in a player who was supposed to be such a talisman. Nobody else was saying much; one or two sipped at coffees. The Young Man looked at his phone to check the time, then he put his phone back in his pocket. Then he took it out again. He had no new messages. The moon was still visible, like a projection, in the early morning sky.

Soon the doors hissed open, and the men and the few women among them climbed aboard their designated coaches. There was an unaccountable smell about the Young Man’s coach. It was his first away game, and he didn’t know anyone. He sat beside a man older than himself and stretched out into the aisle when the coach started to move. The man beside him had a carrier bag by his feet, and from this bag he produced a four-pack of lager. He tore a can from the webbing and offered it wordlessly to the Young Man.

Thanks, said the Young Man, accepting the can. In return, he turned to the man and said, What do you think the score will be?

The man laughed – a bitter, joyless sound. Probably get battered, he said. But you never know.

The Young Man looked past him to the window. It did not occur to ask the man what he was doing here, making such a long and inconvenient journey, if he thought the team would get battered. Instead, the Young Man listened to the rumbling of the coach and the talk behind him – the same man going on about the Finn, still – and watched through the glass as a muted, faded version of the city drifted by, washed out in a film of dust. They drove past a man sleeping on a bench and, a moment later, a pair of teenagers dressed all in black. The Young Man’s gaze lingered on the teenagers. Their colourless dress and their determined expressions and even the way they loped down the pavement made them look like they were up to no good. Coming back from a busy night or setting out into a busy day, perhaps. Either way, the Young Man recognised the type: lost boys whose lives as men had already been written. Finished with school, most likely. Fatherless, probably. Going nowhere, certainly. Then he shrugged his shoulders against the stiffness of the morning and stretched his neck, looking up at the sky. The moon was there, still, but in the rising light of the day it had turned sickly and pale.

The Young Man pulled out his phone again, but no messages had arrived since he last looked. He sighed and returned the phone to his pocket. There was a girl he was talking to: someone he had met through an app and who seemed different, interesting, in ways he did not yet understand. She said she lived on the edge of the city in a shared house full of strangers. She said she was studying for a master’s degree with a loan she would probably never pay back. She said she wanted to do something creative with her life, but she hadn’t settled on a medium and complained that, regardless, she had no impetus to create. They had not been talking long, but the Young Man thought her constant suspicion of the world and its intentions was strange in someone so young. He hoped they could keep talking. For now, however, it seemed she was either still asleep or had gone off him, as had happened in the past. It was not something he could control, but that did not stop him worrying about it.

At the back of the coach, the man in the beanie tried to start a chant, but it was too early in the day for most of the others. Nonetheless, some voices rose to join a watery and half-hearted ode to the Argentinian midfielder they had signed for next to nothing a few years earlier. (Some were saying, already, that the Argentinian was the best player ever to wear the shirt.) The Young Man looked over his shoulder, taking in the morning chorus. He had an image of the Argentinian firing in last year’s goal of the season: a volley from all of thirty-five yards which had stunned the stadium into momentary silence. The Young Man smiled at the chanting, at the memory, and sipped at his beer. He met the eye of the man beside him, but it seemed there was nothing worth saying.

•

Back in the city, the Old Man was waking up. He knew his wife, in the next room, would still be sleeping, so it was with care that he picked up his watch from the side table, stepped into his slippers, and made his way into the living room. The sun had seemed thick enough through his curtains, and now he was more alert, it registered that today was what they called a nice day. A good day for football, he thought, recalling his conversation with the Young Man, the previous weekend. Football weather.

The Old Man’s balcony overlooked a construction site. As he blinked away the last of his sleep, he stood at the sliding door – as was his habit – to see what was happening down below. A few miniature figures, men in hi-vis jackets, busied themselves on the site. The great crane was still, however, and the townhouses appeared no more finished than they had the day before.

The construction work was behind schedule, the Old Man knew. He had read articles about the project in the local newspaper, and he remembered the spiel he and his wife had been given when they moved into the building. He could picture the houses rising into the space which had been made available for them, populating, at last, this new development in which he felt increasingly like the sole occupant. Increasingly isolated. It did not help that his wife was starting to turn in on herself, leaving him with ever more time to spend pacing the narrow balcony like a convict in a one-man exercise yard, shuffling prognoses and test results in his mind. Still, the incremental progress of the construction work was of great interest to the Old Man. He had joked with his wife, when they first moved in, that it was like having an additional television channel, but she was given only to complaining about the dust and the noise.

The Old Man got the door open and stepped onto the balcony, taking in the morning air. He liked it out here, even if his wife was right about the dust. It wasn’t like normal dust so much as sand: an infinitely fine, reddish powder that settled on everything in the vicinity of the site and came back as soon as you brushed it away.

The Old Man ran his finger along the warm metal railing. He lifted it to see dust gathering in the relief of his print, the powder settling in those trenches that marked this hand as his, filling the whorls of his skin and erasing the lines to which no one else could ever lay claim. It made him think of a drought. Disasters on the other side of the world, entire countries in states of crisis.

Noises came now from his wife’s room: the snap of a light switch and then a cough. They had shared a bedroom in their old house, holding out against inevitability for as long as they could. Now his wife finally had her own room. She blamed his snoring, but he knew she had long wanted it this way. At the first signs of her being awake, the Old Man stepped back inside. He slid shut the balcony door and locked it.

Morning, the Old Man called. He listened for a response from beyond the door of his wife’s bedroom as he moved to the kettle. He turned on the kettle at the plug, and then he depressed the little switch to start it boiling. It was already filled with water from the previous day. He took down two mugs from the cupboard above him and set them on the side. Then he spooned a measure of instant coffee into each mug. The smell of powdered coffee rose to fill the kitchen. A tap ran on the other side of the wall.

While he was waiting for the water to cool, the Old Man lifted the sleeve of his shirt. Here a constellation of faded blue dots stood against his skin. He looked at these markings and let himself feel the full weight of the half-century which had passed since then. Here were the aborted beginnings of tattoos he had thought he wanted as a young man, each abandoned at the first touch of the needle. Three times he had steeled himself, each at a different parlour – as they were called then – and each time he had given up before anything larger than a pinhead had been scratched into him.

Days like today, the past pricked at him. Because today was a football day. The team was away up north this afternoon, and in years gone by, he would have been with them. Perhaps in another life, an alternate history, he might yet be on that coach, where he would be identifiable not only by his fingerprints and his singing voice but also by the ink rising in the form of an initialism, a crest, against the dry skin of his arm, proof of the one love nobody had ever asked him to quantify.

3

Simulation

The team was back in the city, and the two men were back in their adjacent seats. They called this place home: this twenty-thousand-seater stadium with its flaking paint and rusting beams. The men could be themselves here, watching in silence as the vast rotating screen cycled through the day’s team sheets. The Norwegian was starting again, despite his poor performance in the first two games of the season. The Finn and the Argentinian and the young Englishman were all in the eleven, as expected. The weather was hot but cloudy: football weather, still.

The Dutchman, in goal, was finishing his warm-up. He took a moment to wave to the fans on the lower terrace, and then he made for the tunnel. The fans behind the goal clapped and started singing the Dutchman’s name, syllables stretching, straining, to fit the tune of an old pop song. The Young Man liked the Dutchman; he was one of those players who fought for the shirt, who understood what the club meant to the people who lived here. And the Young Man thought of the Dutchman as a fatherly presence among younger teammates, a proud and dignified man – the sort who finished the things he started. He was far from the best goalkeeper in the league, but he was their goalkeeper. That was enough for the Young Man, who gestured now towards the Dutchman’s retreating form.

He’s going to have his work cut out this afternoon, the Young Man said.

The Old Man nodded without truly understanding what the Young Man was talking about. He was too preoccupied, today, to make conversation with his new neighbour. He had debated staying at home to be with his wife, but she had told him to go – and to make sure he was there in time for the warm-ups. She knew he liked watching the warm-ups; she had too, once, because it felt like value for money, squeezing extra entertainment from the ever more expensive tickets.

The Old Man thought of her now, letting his mind drift in the manner of the ragged clouds overhead. She had been bad that morning. What had he been thinking, she wanted to know, painting the bloody walls while she was asleep? She thought she had woken up in their old house; she had forgotten, for a moment or two, that they lived somewhere else now. Somewhere that was supposed to be more suited to them, with no stairs to navigate and a construction site beyond the balcony and a service charge which would rise year on year, every year, until they both died and the flat was sold.

The Young Man asked if he could get past. The Old Man looked up, surprised. From the look on the Young Man’s face, he had asked more than once. There was still time, evidently, for one more before kick-off. One more journey along the concrete shelf, past the folded seats and into the concourse, where the bars were.

The Old Man had spent almost every other weekend, almost all his life, rooted to that same strip of cold, scuffed concrete. He had stood on this terrace, once; everyone had. But then football changed, and the club (est. 1902) had been forced to bolt seats to the ledges which rose, like a giant staircase, above the pitch. While part of the Old Man missed those days, he had reached the point now where he was simply grateful for somewhere to sit. In the coming years, as his knees crumbled and his hip pestled itself to dust, he supposed he would be more grateful still. And then – the familiar thought went – one day, he too would have to stop coming altogether.

For the Young Man, these worries were a long way off. He did not know, as he gently shouldered his way to the toilets, how lucky he was. And then he pushed open the door, entering a realm of concrete and porcelain, a space which smelled strongly of men. That urethral tang, the stench of sweat and kidneys, and the unselfconscious drumming of thick streams of piss against metal troughs.

When he was finished, the Young Man dried his hands at the sink, next to a man of a similar age with a young boy in tow. The boy was in full kit, the shirt and shorts and socks glowing pristine and unworn, fresh out of the bag. The father took care to make sure the boy washed and dried his hands properly, guiding him around the puddles on their way out. The boy even had shinpads on; the Young Man noticed this in the mirror, looking over his reflection’s shoulder as father herded son from the bathroom.

When they were gone, the Young Man met the eyes of his reflection and wondered what it was that was so wrong with him. He had cut himself shaving that morning, and a flare of red, a thin scab, had risen on his chin. It looked like the start of a thread that, if pulled, would unravel his entire body, leaving only the clothes he had been wearing (club shirt, club scarf, chino shorts, black running shoes) on the disconcertingly wet floor and no further semblance of him to be seen anywhere.

The Young Man left the bathroom and made for the bar. He had to queue for a few minutes. When it was his turn, he asked for a pint, please. The girl who served him was probably studying at one of the universities in the city. She had her hair in a ponytail, and she was wearing a branded top and a lanyard about her neck to indicate that she worked for the club, if only in this limited capacity. She was pretty, he realised, and then he found himself wondering if she knew the girl he was still talking to – the girl who, it turned out, hadn’t already gone off him after all. He touched his card to pay, and the barmaid smiled and told him to enjoy the match. As much as he was growing to hate his own job – the monotony of the same room and the same desk and the same computer – at least he didn’t have to work weekends. At least he was granted that much: two days kept free for the football. The same, of course, could not be said for the barmaid, who bartered away her Saturday afternoons to serve men like him, each pint valued at around thirty minutes of her labour, her life.

As he drank, the Young Man scrolled back through various social feeds on his phone. Strange things were happening on the continent – something about a build-up of soldiers on a disputed border – and politicians from all over kept meeting to talk about what they would do about it, what might happen next. But the Young Man slipped past the news articles, lingering for a moment on a photo of a girl he had known from school who had been unpopular and undesirable then but was now, improbably, a mother to two children. He typed a different name into the search bar and landed on a familiar profile. He refreshed her feed in expectation of new information, hungry for morsels of her life.

So it was that while the Old Man, back in his seat, was thinking about his wife, the Young Man, in the concourse, also found himself thinking about a woman. He had messaged this girl – to whom he had been talking for weeks now – to say he was at the football, but she had not said anything in response. They were supposed to be seeing each other tomorrow. But signal was always patchy in the concourse and the WiFi never worked, so his feed wouldn’t refresh and her message – if indeed she had sent one – wouldn’t come through. This made him feel better about not having heard back from her, because this way he could imagine her reply had been sent minutes ago and was just stuck, for now, in an invisible backlog. The Young Man comforted himself with this thought as he sipped at his pint, which was valued, incidentally, at around twenty minutes of his own labour. It tasted like the bottom of the barrel.

When kick-off came, soon after the dregs, the Young Man was in better spirits. He had signal again, and still her message hadn’t come through, but at least the game had started, so now he had this to distract him. The beer was probably working, too. And the sun was just coming out from behind a cloud, and the Old Man beside him was clapping vigorously every time their mighty yellows broke into the opposition third. The away fans, likewise, reacted with theatrical fervour whenever their team so much as threatened an attack.

The Norwegian was having another bad day in the centre of the park. Today he appeared especially flaky, misplacing passes and letting his opposite number – a squat, box-to-box bruiser – walk all over him. The fans were starting to get frustrated with the Norwegian, and the men on the terrace groaned as one when he hoofed the ball out wide, up and over the young Englishman’s head and out for a throw-in. Twice more in the opening half he gave away possession, and twice the Dutchman rescued them when the opposition forward broke through, one on one. It was only because of the Dutchman’s quick reflexes that they made it to the break without going behind. The whistle, when it finally came, was accompanied by a smattering of indifferent applause from the stands. The Young Man rose and went in for a half-time piss and another pint.

The deadlock seemed unbreakable in the second half, even after a flurry of substitutions and a change in formation. An Irish teenager made his debut off the bench, partnering the Finn up top, but the Irishman was feeding off scraps and the Finn seemed to have given up pressing. It meant the game was goalless, still, with ten minutes to go.

It was now, however, that the Argentinian, their wildcard, really came into his own. He was one of those players who grew into games; he seemed to become more dangerous in the dying stages of a match, relishing the exhaustion of the enemy. And now the fans cheered the Argentinian forward, applauding as he weaved through a forest of tired legs, daring someone to foul him. He pulled the ball close to his body, dropped a shoulder, and there it was – the inevitable lunge from a defender. There was barely any contact, but it was enough for the Argentinian to throw himself to the turf. He raised his arms, indignant, and looked up at the referee. The referee, seduced, blew for a free-kick just outside the box. The home crowd cheered, while the travelling fans cursed and booed, hurling a cacophony of abuse towards the pitch. You’re not fit to referee, they sang. Who’s the wanker in the black? they asked. Some of the men on the lower terrace gestured for the away fans to pipe down. On the pitch, meanwhile, the Norwegian had come over to start an argument about who ought to take the free-kick. The Young Man could see the Argentinian shaking his head, clasping the ball with jealous hands.

He had this confidence, the Argentinian. His South American flair was celebrated in these parts, even though his magic was often balanced out by what seemed like madness. Last season, for instance, he had picked up more red cards than any other player in the league. But the fans loved him too much to care, and the sporting director who had discovered him would spend the rest of his career basking in the Argentinian’s glow.

Just over three years ago, before he was lured here (the powerful promise of English top-flight football), the Argentinian had been contracted for peanuts in the Spanish second division. He had no real fame; nobody in England knew who he was. But then an analyst here at the club dug deeper into his numbers. A scout was duly sent out to Spain to confirm his talent. The sporting director spoke to the Argentinian’s agent, and in the following transfer window he arrived in England, a gem hidden no longer. The fans knew he was sure to be poached by a bigger club eventually, and they were determined to enjoy him while he was still here. Players like the Argentinian were plentiful enough in this division, but not in teams like theirs.

So the Argentinian took the free-kick; of course he did. And it was a peach, a worldie, the ball bending through time and space itself – or so it seemed – to elude the keeper and bulge the inside netting. The kind of goal that young people on social media would later describe as a sexy goal, a saucy finish. That really gets me going, the Young Man might say, adopting the pseudosexual language with which many young men engaged with the sport. Perhaps because they felt awkward using such language elsewhere and perhaps because it was all they knew.

But right there and right then, the Young Man had no room in his mind for anything besides pure, uncomplicated joy. The ground erupted with him, meaningless noise and four walls of spinning scarves and raised limbs: a scene like the salvation of some twenty-thousand desperate mendicants.

The Old Man, lost in the moment, turned to the Young Man and said, That’s just what we needed, that. The Young Man smiled like his face had split. In the same instant, his phone vibrated in his pocket, and he was sure that he could feel in every individual pore of his bare arms all the places, all at once, where the sunlight was getting in.

4

Hard Shoulder

The Old Man had seen many false dawns in his time, and soon it seemed that the previous week’s victory, the Argentinian’s late heroics, had been merely another. He was following today’s game from home: he and his wife listening on the wireless, confined to their armchairs. When the third goal went in, she reached over and, with an arthritic hand, turned off the radio at the wall. The Old Man said nothing. He merely sighed and diverted his attention through the window to the construction works beyond the balcony. The international break was coming up, already, which meant finding distractions in lieu of club football. Today the huge crane was dangling a claw over the site; he could see it swaying slightly in the wind.

His wife coughed, and he looked over at her. She smiled, taut and quick, to say she was fine and that he didn’t need to start his fussing. He was bothered about the football, but he knew she would not want to listen to him complaining about the game all afternoon. Another shocker for the Norwegian, according to the commentator. He had been directly responsible for at least two of the goals.

The Old Man rose slowly to his feet. Do you want a cup of tea? he asked. His wife nodded in response.

The Old Man turned on the kettle and dropped a teabag into each of their mugs. He looked out of the window as the bags steeped. A pair of gulls flew past at eye level, and he was struck for a moment by the strangeness of this sight, the newness of this perspective. Then he brought over his wife’s mug and set it on the table beside her chair.

Would you mind if I put the wireless back on? he asked.

His wife said nothing. She was already asleep.