Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Istros Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

After nine months of self-imposed isolation following his wife's departure, the hero of Seven Terrors finally decides to face his loneliness and join the world once more. However, when the daughter of his old friend Alex appears in his flat one morning with the news that her father has disappeared, he realises that his life is again about to change. As the two search for clues in Alex's war diary, unearthed in a library in Sweden, they come upon tales of unspeakable horror and mystery: meetings with ghosts, a town under siege, demonic brothers who ride on the wings of war, and many more things so dangerous – and so precious – that they can only be discussed by the dead. As investigation into Alex's disappearance continues, readers will be drawn further and further into a surreal world where rationality has vanished, evil spreads like a virus and not even love can offer an escape. While Charon, Hades' mythical ferryman, can be found behind the wheel of a taxi and dead horses are seen flying across the sky, cracks begin to erode reality and people start to go missing. Here, amidst such chaos, our hero endeavours to cling to his sanity, doing his best to solve the riddle of Alex's disappearance while attempting to save his own soul and bring love back into his life. Startling, unusual and intense, Seven Terrors may well be considered the perfect post-war nightmare. "It's quite unlike anything I've read before, but it has all the consistency and force of something major and assured. (Remarkably, this is the author's first novel.) That it has room for humour is testament to Avdić's confidence" Nick Lezard This book is also available as a eBook. Buy it from Amazon here.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

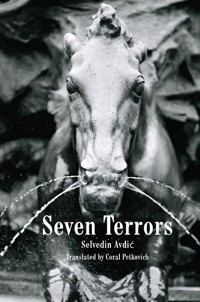

Seven Terrors

Selvedin Avdić

Translated from the Bosnian by Coral Petkovich

Istros Books

Istros Books London, UKwww.istrosbooks.com

Copyright © 2012 Selvedin Avdić Translation © 2012 Coral Petkovich Cover image courtesy of Guliver Image d.o.o. Zagreb The cover design of this book is based on the original design forSedam strahova (Algoritam, Zagreb, 2009)

All rights reserved, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher.

eBooks ISBN-13: 978-1-908236-93-7

FOREWORD

by Nicholas Lezard

Horror stories have to convince us of their veracity. The convention is to say ‘This really happened’, and it is a convention we assent to as we read. And so Seven Terrors begins with the mention of a date, 7 March 2005, and the front page of the Bosnian newspaper Oslobođenje for that day, which shows ‘a photograph of a municipal worker cleaning an enormous pile of snow from some street in Sarajevo’. The paper, then, subliminally serves in a similar way to a newspaper being held up by a kidnap victim: to corroborate, to prove to the outside world that this has not been faked. It is deftly done, and we are going to need this assurance for the book to get under our skin.

However, it is not quite as simple as that. Our unnamed narrator, we quickly learn, has remained in bed for nine months, a period of time that can’t have been chosen accidentally: a gestation. What is being given birth to is what the novel is about: a nightmare version of the world, in which everyday objects – radios, cigarettes, diaries – co-exist with spirits, djinns, visions of the Apocalypse, folklore made real. ‘I do believe,’ says the narrator early on, ‘not only in ghosts, but also in vampires, were -wolves, apparitions, fairies, witches, giants, magicians…’ The list is long and reads like one of the wilder passages from Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. It has the strange effect of not only emphasising the narrator’s credulity but also undermining it. It is a satire of belief, almost. It ends with the words, unqualified, ‘Bosch’s paintings…’ and that we can assent to. I, for one, have seen them on the walls of the Fine Arts Museum in Brussels and can tell you that belief in Bosch’s paintings is not silly. Yes, you say, but you know what he means. The monsters and all that. But our narrator doesn’t say that, and even this early into the book we already know that he is very careful indeed about the way he puts things. There is something else going on here.

That something, of course, is the Bosnian war of the 1990s. Perhaps in this country we underestimate the shock, the absolute inversion of normality, that happened when the countries of Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia, long dormant under the cold mantle of communism, woke up and started tearing each other apart. It was as if this corner of Europe had been shot back fifty years to the darkest days of the Second World War. With this nightmarish difference: that the enemy didn’t necessarily come from a different country, or a different area, or even a different street: the enemy could come from next door or even be lodging in the same house as you.

And it was horrific. Eye-witness accounts of the siege of Sarajevo regularly feature the surreal carnage of human destruction: basically, body parts strewn all over a market square. Leave the carnage to one side and turn to the bureaucracy of war, and you have something very similar being visited upon the Muslims of the area as was visited on the Jews in Nazi-occupied countries. Sample deprivations: in one town Muslims were not allowed to move around town between 4 p.m. and 6 a.m., associate or ‘loiter’ in streets, cafes, restaurants ‘or other public places’ (I am, by the way, taking this from Ed Vulliamy’s book on the war, Seasons in Hell), bathe or fish in the river, drive or travel by car, etc., etc. The point is to make life literally impossible. In Banja Luka, Muslim women were banned from giving birth in the local hospital. The Serbs and the Croats got round to building concentration camps, with this nice twist in these untroubled lands: journalists from Spiked magazine asserted the photographs were faked. (And so from this we can date the birth of our own modern era of ‘fake news’, of the malleability – or rather, the deniability – of truth.)

‘And what was normal during the war, fuck you?’ asks a character at one point in Seven Terrors. ‘Tell me one normal thing!’ (I hope that that ‘fuck you’, oddly tacked on as part of a question, is an honest representation of the original language. It suggests that not even the words ‘fuck you’ ended up in their normal syntactical position in the war. Or this book.

The book does not mention the war very much. That’s not its job. It sees the war out of the corner of its eye, and yet everything in it is post-war: after this, nothing was the same again, and even normality is compromised. (We learn that the Music School became a place of torture – ‘our gift to the town’, say the extra -ordinary sinister and omniscient Pegasus brothers, themselves incarnations of Jedžudž and Medžuž, the announcers of the Islamic apocalypse.* ‘After all the awful things that happened there, the town is no longer innocent and won’t be ever again.’ [Italics mine.] And yet normality is still there. How can you describe a world in which there is both Vogue magazine and snipers firing at people trying to do their shopping? With great difficulty, is the answer, and maybe you have to invoke the supernatural to do it. Yet even the supernatural is insufficient: you need to describe the real world, and for added authority you put in footnotes (which are one of this book’s many treasures and evidence that Selvedin Advić, whose first novel this, astonishingly, is, is not without a sense of humour).

I have said elsewhere that this is a book in which two worlds are often in contrast, if not in conflict: the living and the dead, the time before a woman leaves a man and after, the pre- and post-war world, the spirit and human worlds, madness and sanity, dreaming and reality, Muslim and Christian, Muslim and atheist. From these tensions something crackles like electricity.

Nicholas LezardLondon, 2018

* ‘Who are Jedžudž and Medžuž?’ is a question that the narrator bursts out with at one point. We’re never told, so I’m telling you now.

Whoever ends up reading this text will not be my choice, as I have no say in the matter. Maybe that’s a good thing, because I’ve never managed to choose the best option in my life. So let chance decide and hope it doesn’t bring me some insufferable cynic.

This story, which I wish to retell in the best possible way, begins on the seventh of March 2005. On that day, the daily newspaper Liberation published a photograph of a municipal worker cleaning an enormous pile of snow from some street in Sarajevo. In the same issue, on the fourth page, a photograph of the village of Ljute na Treskavici appeared. On the pale imprint of the photo the roofs of the houses emerged from the drifts of snow, and the heading informed us that the heaps were seven metres tall.

Almost the whole of winter passed between alternations of fog and rain. At the beginning of March, the snow began to fall as though it had gone mad. The flakes were small and round like balls of Styrofoam, but persistent; they were pouring down for days. The town children delighted in them for the first few days. They made slides on every slope in town, and sledges were scraping the streets until late at night. But soon they became bored, so that this March ought also to be remembered as the time when even snow succeeded in being tedious for the children. By the time the last sledges abandoned the streets, the snow was purely an inconvenience.

These things happened not long ago, so I can remember the details quite well. In fact, I shall endeavour to convey everything exactly, because that is, after all, in my own interest. Maybe I won’t succeed in retelling precisely the exact words of certain conversations; that is understandable; but I shall try to reconstruct them as truly as possible. They are very valuable for the continuity of the story. And I shall be completely sincere; while lies are attractive, they are also too expensive. And I’m not quoting here, I am speaking from experience.

I shall start the story like this.

I had spent nine months in bed. I wasn’t ill, I felt quite alright. Physically, at least. Or at least nothing worse than usual. It was simply that I could not find a strong enough reason to leave my bed. I would lie for hours on my back and watch the rays of sunlight coming through the holes in the blind. I listened to the gurgling of the water pipes, the muffled voices of my neighbours through the walls, the creaking of the mechanized lift, the claws of the pigeons scrabbling on the tin window sills. I stared at the ceiling, ate sweet biscuits dissolved in water…slept…and that was all. That was all I did during those days, and all I wanted to do. I was not happy. Later on I shall explain to you why not. For now, so that at the very beginning of the story I do not leave any parts unclear, I shall point out that after ten years of marriage, my wife, who I always thought could not imagine life without me, had left me. As there is no place for lies in this story, I shall admit straight away that her departure was entirely my own fault.

On the night between the sixth and the seventh of March, all at once and without any reason that I could understand, I decided it was time I left my bed. On Monday, the seventh of March, 2005, I returned amongst the living. I opened my eyes at the first sound of the alarm clock, exactly at seven o’clock. I washed myself, cleaned my teeth, and even did my morning gymnastics, four push-ups which made me dizzy in my head and nauseous in my stomach. Then I lit my first cigarette. Oscar Wilde, if I remember rightly, said that cigarettes were the torches of our self-confidence and that with their help we could withdraw into the sphere of private perception. Cigarettes are for me a bad habit, a drug which does not take hold and, maybe, a mild remedy offering peace of mind. Besides, I’m never alone with a cigarette, as the classic advertisement says.

With this company between my teeth, I set off on my first adventure. I suppose I don’t have to explain that I was nervous, frightened, unsure. But, it was time for a change. I wrapped myself in my coat and went outside. I wanted to start the morning with newspapers, to read about what I had missed over the past nine months, how the world had been stirring around my bed. A light wind was twirling the little snowflakes in the air. Some of them fell behind the collar of my coat. They were not unpleasant. I grabbed the copy of Liberation, quickly, so that the saleswoman didn’t have time to start a conversation, left my change and sneaked back to my flat. I put my coffee pot on the stove and turned the radio on. ‘The Rolling Stones will be playing a song for you this morning. We’ll be listening to ‘Street Fighting Man’, whose musical legacy was recorded long ago, in 1968.’ The voice of the radio host was serious, almost moved to tears, as though she were reading a report about the death of someone important. That announcement awoke in me a long-absent sense of calm, an old-fashioned peace, a feeling of safety which smelt like childhood. Such a feeling had not visited me for a long time. I stretched and tried to breathe it in, to feel it in my nostrils, my lungs, to hold onto it so as to be able to remember it well.

I drank my coffee, listened to the musical legacy and watched through the window as people pushed their way through the snow, which had grown another three feet during the night. Above them, a flock of tame white pigeons was flying round and round. I opened the newspaper. At the top of the second page, I found an article saying that since 1995 the teams from the Federal Commission for the Search for Missing People had found 363 mass graves and from them exhumed 13,915 victims. On the fifth page, the Epidemiological Service of the Federal Institute for Public Health warned that bad weather increased the risk of infectious diseases, especially capricious respiratory diseases, and meningococcal infections, but also others such as hepatitis, stomach typhus and dysentery. On the pages set apart for world news, Giuliana Sgrena, a journalist from the Italian newspaper Il Manifesto, described how she had been freed from prison in Iraq, and accused American soldiers of firing at her car. All of Italy, stated the local reporter from Rome, was mourning the late Nicola Calipari, an agent of the Italian Secret Service who had been killed by an American patrol. Vladimir Putin was preparing for the celebration of the Day of Victory over Fascism; Jacques Chirac promised that he would support Palestinian independence, and the boxer Mike Tyson, at the festival in San Remo, had sung a version of the song ‘New York, New York’. The television program offered viewers the choice between three films – the action thriller Once in a Lifetime, the melodrama And That’s Love and the biographical drama Frida.

While I was thinking about what kind of film would suit the first day of my return to life, I heard someone knocking on the door: three times, lightly. At first, I thought I had misheard, since it was a long time since anyone had knocked on my door, so early in the morning. But then came another three knocks, followed by the bell. I got up from the chair, went towards the door and then stopped abruptly. In the mirror, I came across a melancholy, crumpled and pale image. I was wearing misshapen trousers full of glistening, luxuriant spots and a jumper that had once, before the war, been green, with a big sign on the front denoting the Mahnjača factory. It crossed my mind that it would be a good idea to change my clothes; then decided that there had already been enough changes in my life for the first morning there.

Mirna stood in the doorway. Fresh and smiling. Behind me gaped my one-bedroom flat, like the mouth of a giant with bad teeth.

‘Good morning. I’m not too early, am I?’

It was then that I remembered. I remembered that there had perhaps been one more reason for me getting out of bed that day. The night before, I had spoken to Mirna on the telephone. She had woken me up and I had been drowsy, so I couldn’t recall what we’d been talking about. At the time, I’d only wanted to finish the conversation as soon as possible and to return to bed. But she must have said she wanted to see me, or something like that, because there she was, standing there in the doorway with a wide smile.

‘It looks as though I haven’t come at a good time.’

I hitched my trousers up on my hips, looked back around the room and answered:

‘You know, actually you haven’t. Please, can you come back in an hour?’

My voice was hoarse, squeaky and hollow, woken up from a long silence. But she understood, smiled again, nodded her head and went away down the staircase.

The hour which I had wheedled out of her was intended to give me time to spruce up the flat; despite not really believing that she’d return. I know that I wouldn’t have done in her place; I wouldn’t return if the person who was waiting for me looked, thought, behaved and, generally, lived as I did. Since that was what I truly believed, I went back to the chair and sat down. For, after all, I was not in the least bit happy at the time…

I tried to remember the telephone conversation with Mirna, but without success. I had known her superficially, in that time before the war, when I knew many people in that way. We had talked only a few times. She liked painting and I think that was what we mostly talked about, even thought I am far from being an expert on that topic. It must be that the people she had met knew even less, because she followed every comment or flimsy conclusion of mine with enthusiasm. Then, during the war, she just disappeared. I didn’t even notice when she left because at that time everything was disappearing – people, habits, things, customs, a whole pile of words. The town itself changed, almost completely. I got used to people going away, somehow quite easily, just as I adopted as a normal occurrence the shortage of food, water, electricity. Just as Čoka liverwurst had disappeared from my life, in the same way I noticed that a friend who had used to enjoy it was missing too.

When the doorbell rang, I realised I was wrong: she had come back. Then I was sorry I hadn’t at least pushed the old socks and dirty plates into a corner. But in front of the door stood Ekrem, the caretaker in the apartment building and a taxi driver out in the street. In his hand he held a large notebook, with the pages criss-crossed with tables of numbers.

‘Up early, neighbour? Payment for the cleaning lady, you know we collect from the tenants on the seventh of every month. Since you are still among the living, you owe nine months.’

I turned around to get my wallet from the pocket of my coat, knowing full well that, during that time, Ekrem was craning his neck to look into the flat. He always did that, forcing housewives to be careful to clean up a bit before his visit. When I turned back again, he took a quick step backward, smiled and indicated with his chin towards his fat stomach.

‘Pretty good jumper, eh neighbour?’

The woollen jumper, with a big stylised deer baying at the moon, was stretched across his stomach. I nodded my head.

‘I earned it with my cock – he informed me with satisfaction.’

I knew that too. He was always bragging about how his ex-wife was still sending him presents from abroad, even though she was married to some German pensioner. What Ekrem was trying to explain was that she was buying him presents in gratitude for those wild nights and in honour of his phenomenal sexual expertise.

‘How are you? Or is it better not to ask?’

I nodded my head again and gave him the money. He winked at me and held out the notebook for me to sign. I shut the door and heard him ringing the bell on the door across the way: ‘Up early, neighbour…? Nice jumper, eh?’

At that point, I decided to tidy up the flat a bit, after all. Just in case Mirna came back. I didn’t take too much care; I just put away those socks and plates. I didn’t have the strength to do much else, so I went back to the chair and waited…

Outside, a man and a woman were playing with a little girl in the snow. The man shut his eyes with his hands, and the other two, giggling, looked for a hiding place. They found it in a small cave scooped out of the snow. The man opened his eyes, fell to his hands and knees and began to sniff their footprints. His big moustache was cleaning the snow in front of him. When their tracks led him to the hiding place, he barked loudly, made a forward somersault and rolled inside. After him, with much more creaking than necessary, a small snow-covered door shut. A flock of white pigeons circled above, faster and faster, until they became a shimmering disk. The disk formed into an arrow which for a short time was calm in the sky, then turned towards the earth and swooped down with a hiss. While the birds, like large darts, burst like machine-gun fire into the snow, the radio behind my back started playing a fanfare and the doorbell began to clamour. I smoothed down my hair and turned the handle.

In the doorway stood a man with big, blood-shot eyes: the biggest eyes I have ever seen in my life. He said something to me, but no matter how much I tried, I couldn’t understand a word. His small mouth moved like earthworms in the mud as repeated what seemed to me to be the same words. I asked him to say it again, I told him I couldn’t understand a thing, but he didn’t listen. He seemed veiled by his huge eyes, which somehow prevented me from seeing the rest of his face. The dark pupils swam in blood and in their clear reflection, my frightened face lay suspended. His mouth moved faster and faster, it seemed that he even reached the point of shouting, but I couldn’t know for sure… And then I woke up.

Darkness had already drawn long shadows in the snow by the time I opened my eyes. The clock showed that I had slept through the whole afternoon, which was nothing unusual. At that time I could sleep constantly. It was enough for me to sit down, to stretch out my legs and already my vision became cloudy. No matter how long I slept I was still always sleepy. But it was enough sleeping. I went to the bathroom with the firm decision to wash myself. Turning on the tap, I gazed into the stream of water. It was magnificent, shining, fresh. I could have looked at it for hours. In fact, I did.

Mirna didn’t come back that day. I waited for her on the chair, gazing through the window. Snow was still falling, as though it wanted to stop the very life of the town. But it was not successful. People kept stubbornly trampling on it. They passed by in front of the window and made paths which crazily multiplied and crossed without any order at all. It was hard to find any space in the snow on which no-one had stamped. In order to find fresh snow you had to get up very early, before everyone else, otherwise there was no sense going out, for you could watch everything from the window. I succeeded in finding out which window was the first to light up in the neighbouring apartment block. Then I finished watching half a movie (I decided on the love story) and turned over a few pages of a book. I don’t remember which one, but I do remember thinking that it was enough for the beginning of my return to life. And then I finally fell asleep.

The next day, around midday, I stood before the window with a big cup of coffee. On the radio a cook was explaining how to barbecue fish – ‘for a thickness of three centimetres you need ten minutes’ – or something like that. On the street, women were carrying bouquets of flowers. Every single woman had at least one and to me it seemed as if they were carrying them like a trophy or like a conductor’s stick. Then the doorbell made its announcement and in front of the door stood Mirna, with an even bigger smile than yesterday.

‘Today you have to let me in. After all, it’s International Women’s Day.’

Indeed, it was the eighth of March. She came inside, and suddenly I was completely unnerved. I recall feeling that I couldn’t remember how to entertain a woman who had called by unexpectedly. I offered her a cup of coffee, but she refused and in so doing, deprived me of the one idea I’d had. I sat down on the chair and put my hands in my lap. But, even confused like that, I still enjoyed the sight of her sitting in my kitchen.

Maybe this is the right place to describe Mirna for you. It would be good if I could find some well-known woman with whom I could compare her, but I can’t think of any such person. She has black hair, cut short, almost regulation Yugoslav National Army length. You could say she is short, a few kilograms overweight, with a large mouth which would perhaps look better on a bigger face. Her eyes are black, with a ball of light in the centre, and her smile is her best feature: sincere, warm and ready to reveal itself at the slightest provocation. Such a smile can be like a remedy. Her smile made Mirna a beautiful woman, yet she was still not more beautiful than my own wife. (I compare all women to my deserting wife. Just as religious fanatics see a prophet’s face in every stain, I recognised my wife in every other woman.)

It has occurred to me how I can best describe Mirna: she was somehow pure, with precise lines of body and face, as though a photomontage had been placed in my kitchen. I don’t how long I sat staring at her, but it seemed to me that she wasn’t bothered by it. She didn’t speak, she only smiled. Silence did not seem to worry her, whereas it drove me crazy. Yet still I did nothing to break it. In fact, I even sustained it; I started to observe the flat through her eyes and immediately came to the conclusion that she could not possibly like it. Dust covered everything; if the room could have been shaken up thoroughly, large pieces of fluff would have kicked up a storm like inside those little snow-domes. Not one object in the flat had any shine, all the colours were subdued, and even the morning light was not having any effect, as though the gloomy room was soaking it up. Yet I couldn’t move the curtains apart, for I was afraid a stronger light would uncover much worse things. I got up from the chair, smiled feebly in lieu of an explanation and opened the window to at least get rid of the smell of tobacco, sweat and used up oxygen – the smell of loneliness. Then I thought that some music might help, recalling how it can easily change the atmosphere of any room. Do an experiment, if you don’t believe me. In a completely empty room, play different types of music and you will see how the shadows shift, the air stirs, the nuances of light change, as the room adjusts itself to the music, like the scene changing from act to act in the theatre.1 There is no such thing as complete silence. It does not exist. At least not in this world, maybe in outer space or in the bowels of the earth, where it’s only cold and dark. I put a CD into the tray of the player. I can’t remember which one.2 I seem to remember the playing of slow trumpet music. That’s what I put on when I am feeling nervous. And at that time, if I remember rightly, I was rather nervous.

Mirna waited patiently for me to finish my preparations. I went back to the table and all at once we began to talk, as though we had accidentally tuned into the right frequency. She talked about Sweden, their big wide libraries where the books are arranged like sculptures, she boasted how she too could walk around in winter weather with wet hair and not catch cold, and she told me a story about the most nervous animal in the world – the Yarva, which cannot tolerate another Yarva within a hundred square kilometres. I didn’t say much; mainly I just threw in comments between her sentences about how different it was here now, compared to before the war, and at the same time, somehow the same; and yet, of course, very different from Sweden.

We talked for a long time like that, maybe two whole hours, and all the while I was waiting for the moment when she would finally mention the reason for her visit. It seemed to me that she consciously procrastinated and kept quickly trying to invent a new theme, just to fill up every last piece of silence. She told me how in Sweden she avoided people from our country, that they were divided into national clubs where they hugged one another to the sounds of turbo-folk, and fought against a background of nationalist patriotic songs.

Suddenly she asked me, ‘Do you remember my father?’

Of course I remembered Aleksa, we were friends. I knew him much better than I knew her.

I nodded my head, and she asked me a new question, ‘Did he drink a lot?’

Of course I remembered that Aleksa drank a lot more than he should have. Just before the war, when the disaster could already be foreseen, his thirst suddenly began to grow. In the beginning he tried to hide it. He would go to the kafana, hurriedly, in a business-like manner, greeting the guests with a small inclination of his head, and he would order a double brandy. As soon as the waitress put the glass on the table, as soon as it clinked on the wood, Aleksa would grab it, swallow the alcohol down his throat in one gulp, put the glass down on the bar with a ringing sound, and depart. This time without any greeting. All that in a few seconds: tick-tock-tack and outside. Afterwards we learned that he repeated the same ritual in a whole series of different kafanas.

As soon as he left the first, he went across the road to the next one, and then he went down the boulevard, went into the kafanas he found there, called in at the deserted hotel bar, and from there went over to the kafana at the bus station, then the little grill place where taxi drivers warmed themselves; from there to a few more cafes where at night techno music was buzzing, then to the Lovers of Small Animals Club, then the theatre bar, the pizza place, and the billiard club; he went down the main street, drank one more at the kiosk on the marketplace, and in the express-restaurant. After two hours, and having made a complete circle, he returned to the first kafana. He stood in the doorway, blowing on his hands to warm them, as though he wanted to give the impression that he had endured a hard working day. He greeted the waiters loudly and heartily ordered a double brandy, then sipped it slowly, already completely drunk. We quickly discovered what he was doing, but no-one let on. His manoeuvring to quench his monstrous thirst we called ‘Aleksa’s Brandy Circuit’. I didn’t see him often during the war, but I doubt he was able to break such a strong habit.

I didn’t tell her all that. I only mentioned that during the war there had not been enough alcohol for anyone to ‘drink a lot’.

‘Aleksa just drank a bit, on occasion, like all of us…’

That is exactly what I said to her. I thought an answer like that would please her, but it did not. Her nostrils quivered. I asked her why that interested her.

‘I am interested in everything to do with my father. That’s why I came here.’