Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Shams is a young Syrian refugee woman who lives in Shatila, one of the world's oldest refugee camps. She dreams of education and living a better life in Europe. But there are no schools in the camp, and her family opposes her dreams. Mr Tony, a poet running a charity, seems to offer a way out. But the camp appears to be taking on a life of its own, as a malevolent, all-consuming and seductive presence.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 116

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iPraise for Magda

‘Challenging, clever, and fascinating as an insight into how generations of Germans are summoning the courage to address the horror of the last century.’ —Amanda Craig, Independent

‘A book we should all be reading, so find a copy. It has been one of my reading experiences of the year.’ —Simon Savidge, Savidge Reads

‘This is an intelligent, acute and horrifically intense book. It didn’t so much take my breath away as make me gasp for air.’ —Sam Jordison, The Observer Books of the Year

Praise for Clara’s Daughter

‘The deftly arranged sequence of scenes gradually reveals the fears and needs of each protagonist and their relationships with each other, outlined with a careful, thoughtful style that creates an unusual atmosphere of charged bleakness. Strange, but oddly impressive.’ —Harry Ritchie, Daily Mail

‘This searching, beautifully written novel gets to the heart of a woman’s attempts to step out of the role of her mother’s daughter, and make sense of the person she has become. Terrific.’ —Kate Saunders, The Times

Praise for Kauthar

‘Kauthar, as much an exploration of breakdown and collapse as of the lines between devotion and delusion, faith and fundamentalism, does not shy away from suffering and darkness; instead, as in Magda and Clara’s Daughter, Ziervogel goes bravely to the bleakest points of humanity and illuminates them with her lyrical and enthralling prose.’ —Claire Kohda, The Guardian

ii‘Ziervogel writes with insight and fluency, articulating a profound empathy with those at the extreme reaches of their endurance. Searingly contemporary, Kauthar sketches out a humane and subtle counterpoint to the distorted debate surrounding religious radicalisation, and in doing so is resonant and timely.’ —Lettie Kennedy, The Observer

Praise for The Photographer

‘Two generations on from her own grandmother’s experience, Ziervogel shines a humanising light into the dark spots of her country’s history.’ —Lucy Ash, The Observer

‘Few books have the ability to move the reader in the first pages, as The Photographer does … Ziervogel makes us question ideas of innocence and blame during fraught times … [she] shows us the less visible effects of war, and the ways in which it can corrupt and change us.’ —Claire Kohda, Times Literary Supplement

Praise for Flotsam

‘Ziervogel … grew up in Germany and this taut, mysterious novel not only conjures female subjectivities and grief, but it also paints a haunting portrait of the country in the 1950s, with its greater sense of loss, and the looming spectre of crimes committed during the war.’ —Arifa Akbar, The Guardian

‘Anna’s experience of World War Two and the consequences of an event in the war, dominates her daughter’s life. Flotsam asks how will the next generation live in the shadow of such destruction, when so much of that history is left silent? Wonderfully concise yet powerful, Flotsam seems simple while offering a layered intelligence that should be valued.’ —James Doyle, Bookmunchiii

iv

v

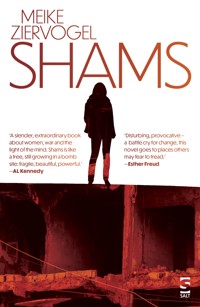

MEIKE ZIERVOGEL

SHAMS

vi

vii

To the Alsama studentsviii

ix

لن تستطيعي أن تجدي الشمس في غرفة مغلقة

You can’t find the sun in a locked room.

—Ghassan Kanafani

Note: the Arabic word for ‘sun’ is شمس / shams

x

CONTENTS

PART ONE

2

1

Outside, in the city, life begins early, between four and five in the morning. That’s usually when she goes to sleep, and she doesn’t stir until well into late morning, more like around noon. She’s getting on now, in her eighth decade. She shouldn’t really be here anymore – her type isn’t meant to survive for more than a few years. But recently she’s been kept busy, she’s in demand. Her folds have become deeper and darker, more dangerous. Though also softer. Whoever comes, she takes them in, puts her huge arms around them and pulls them close, towards her belly. And there they then lie, like babies, like lovers – men and women and children, old and young and newborns. Some fall asleep straight away, surrendering to her oozing, sweet-sour stink. Others suck her nipples, play with her breasts, explore her folds with their tongues, their fingers, their penises. She lets them. It’s their right. Eventually they all fall asleep. And that’s what she’s waiting for. Then she draws them even closer, right inside her, and curls up around them, and buries her nose in their hair, and rocks them gently, ever so gently, from side to side, humming quietly, no particular tune, a mix of Umm Kulthum and Fairuz and Amr Diab and Fares Karam and the call to prayer. Her children, she gathers them up, she loves them all and she protects them. She strokes heads and absorbs fears and nightmares, screams and tears. She lets them rage against themselves and against the world, and if they harm themselves and others, what does it matter? She loves and forgives and lullabies them into a beautiful sleep. Forgetting and escape, these are what she offers.

She likes to imagine herself as a big fat mother, one of those ancient fertility goddess figurines, usually crouching, with a belly 4that has many folds and with massive heavy tits hanging down, eternally filled with nourishing sweet milk for all her thousands and thousands of babies. Her hips sway when she walks, and her folds swing, and her thighs rub against each other and her laugh covers the earth.

She’s a shapeshifter. What she imagines, she is. Yet at a blink of an eye her true nature appears. All wires and vessels and tubes and tendons and sinews and cancerous growths and brittle bones turning increasingly crooked by the day are there for everyone to see. Her skin, deprived of the sun for decades, has become so thin and transparent that it might as well not exist. She pees and shits in the narrow alleyways, self-respect a word without meaning. And with the thunderstorms in winter her watery embrace becomes deadly, while the lightning that charges through her veins electrocutes whoever dares touch her.

Shatila is her name. One of the oldest refugee camps on earth. In Arabic the word means ‘justice’ and ‘insight’. She runs the best whorehouse in town. You can get women, and girls and boys, and body parts and weapons and drugs. If you pay, you get. And no one bothers you. In her house, she alone is the law. She will protect you from the forces outside and rock you to sleep. But the house rules are tough. You might be raped or robbed or kidnapped. Tough luck. Do not complain. That is the deal. Just come and crawl into her arms and she will sing you to sleep.

The older she grows, the more alluring she becomes. Travellers arrive from afar looking for a thrill, a kick, wanting to touch her for just a moment, to lay their eyes on her. Others study her, write theses about her. Sometimes they stay for a week, sometimes for a month, but rarely longer. Danger and ugliness and evil reside within her. If you don’t have to stay, you leave.

2

‘I’ll come back for you,’ Omar says.

Of course he says it. And in that moment, he believes what he says, and Shams believes him too. After all, they are young.

They stand huddled against the dilapidated wall inside the scrapyard on the edge of the camp. To their left and right lean big rusty red-orange and purple-brown sheets of metal. Someone, probably the profoundly deaf who guards the yard after hours and earns a good income on the side by providing a secret spot for lovers, has pushed the sheets aside so that the thumping noise couples might produce against the wall will not be heard. The call for the Maghrib prayer has just begun, but Omar and Shams aren’t the first this evening. Omar kicked a used condom to the side, hoping that Shams wouldn’t notice. But she did notice. And anyway, she knows what she wants. She’d furtively pressed an extra five thousand into the hand of the old man once Omar had already turned inside the yard, to buy them a few more minutes.

With a slow, deliberate movement, Shams now pulls her hijab back. She has come prepared, wearing it more loosely, with no underscarf. She releases the big hairpin, her thick black hair uncurling to the bottom of her spine. Many times she has practised for this moment, imagining the situation in front of the small mirror above the kitchen sink in the early morning when everyone else is still asleep. Now, it has the desired effect.

‘You are beautiful,’ Omar gasps, running his fingers gently through her soft hair, then twisting it around his hand and bringing it up to his nose, inhaling the rose oil. The acrid smell of the scrapyard vanishes from his senses.6

For a moment Shams’s eyes remain open, taking in the yard. Pipes and dismantled cars and old washing machines and broken fans. Machine junk looking like slaughtered aliens. An iron taste is settling on her tongue. She closes her eyes. Their lips touch. They kiss. She wants more, so much more. Omar will save her from this inhuman world. He will take her to Norway. With him by her side she will become happy. She already knows that she doesn’t want to live without him ever again. In her eyes he is already her husband.

And she needs to be quick about choosing her own husband. Otherwise, her aunt will do it for her.

‘Fadel has asked for your hand and I have agreed,’ Shams’s uncle announced a few weeks ago.

Shams has lived with her uncle and aunt in the camp for as long as she can remember. Back in Syria she used to have a father and a mother and two brothers. Now Shams’s family do not even visit her in her dreams.

Fadel is a cousin on her aunt’s side. He is ugly and dim-witted and fat. And old: thirty-something.

Shams was not surprised. She had expected her aunt to start bringing her suitors. Most girls in the camp are married off at around her age, sometimes even younger. Sheima, her best friend, is now married and already pregnant, and Afifa, one of her second cousins who Shams likes even though the girl is three years younger, can’t stop talking about getting engaged soon.

Early marriage eases the burden on the family as there’s one less mouth to feed, and also earns them some money, while at the same time, if the man comes from the same clan, the girls and the money stays within the tribe. What’s more, the teenagers themselves want it. It’s the only way they can have sex without bringing shame on their family.

Shams heard herself say, ‘My mother would have wanted me to finish my education.’7

Shams’s mother had been allowed to go to school, while her older sister, Umm Ali, never even learned to read and write. Umm Ali and Abu Ali are both illiterate and before the war had never left their village.

If Shams had already known Omar when her aunt suggested Fadel, she would have said, ‘I’m in love with Omar and I will marry him. He’s travelling with his family to Norway and when I’m eighteen I will go and live with him there. In Norway all girls go to school, even if they are married. Afterwards I will go to university and become a lawyer to fight for the rights of girls around the world. And you can’t stop me.’

Shams’s uncle jumped up, raising his hand to hit the girl who managed to duck, taking a step back. Umm Ali grabbed her husband by the shirt, pulling him back down onto the mattress where they were sitting. Shams had just served her uncle and aunt tea, and they were sharing a shisha.

‘I’ll talk to her,’ Umm Ali said, smoke rising from her mouth. She gave her husband a light push on the shoulder to encourage him to leave the room.

‘You are no longer safe here,’ Umm Ali said when he had gone, looking her niece straight in the eyes. ‘You are a girl of marriageable age. Men have begun to notice you.’

‘You mean my cousins.’ Shams’s words were barely audible but she couldn’t speak louder without betraying the tremble in her voice. ‘They have noticed me for a while,’ she continued, ‘and it’s never seemed to bother you.’

Five of Umm Ali’s youngest children are still living at home, including two teenage boys, everyone sleeping together in one room. Ahmed tried to rape Shams from behind one night, but she had noticed his glances for weeks and been prepared. She put a knife to his throat and when he offered her money if she let him finish what 8he wanted to do – after all, it was from behind and would leave her a virgin – she had pressed the knife ever so slightly into the skin of his neck until a little red dot appeared.