5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Shadowpaw Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

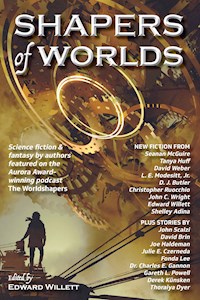

Within these pages lie eighteen stories, from eighteen worlds shaped by some of today’s best writers of science fiction and fantasy, all guests on the Aurora Award-winning podcast The Worldshapers during its first year. There are original stories from Tanya Huff, John C. Wright, L.E. Modesitt, Jr., Shelley Adina, Seanan McGuire, Christopher Ruocchio, D. J. Butler, David Weber, and Edward Willett, plus additional stories by John Scalzi, Julie E. Czerneda, Derek Künsken, Thoraiya Dyer, Gareth L. Powell, Fonda Lee, David Brin, Dr. Charles E. Gannon, and Joe Haldeman. Some are international bestsellers. There are winners and nominees for the Hugo, Nebula, World Fantasy, Aurora, Sunburst, Aurealis, Ditmar, British Science Fiction Association, and Dragon Awards. Some have been writing for decades, others are at the beginning of their careers. All have honed their craft to razor-sharpness.

A teenage girl finds something strange in the middle of the Canadian prairie. An exobiologist tries to liberate a giant alien enslaved on its homeworld by humans. The music of the spheres becomes literal for an Earth ship far from home. A superhero league interviews for new members. Strangers share a drink on a world where giant starships fall. Two boys, one a werewolf, one a mage, get more than they bargained for when they volunteer to fight an evil Empire. A man with amnesia accepts a most unusual offer. A young woman finds unexpected allies as she tries to win a flying-machine race in steampunk London . . .

Ranging from boisterous to bleak, from humorous to harrowing, from action-filled to quiet and meditative; taking place in alternate pasts, the present day, the far, far future, and times that never were; set on Earth, in the distant reaches of space, in fantasy worlds, and in metaphysical realms, each of these stories is as unique as its creator. And yet, they all showcase one thing: the irrepressible need of human beings to create, to imagine, to tell stories.

To shape worlds.

Praise for Shapers of Worlds

“One of the most wide-ranging volumes I’ve encountered in terms of sub-genre. It’s rather like a speculative fiction buffet, offering steampunk, fantasy, military fiction, magic, space opera, post-apocalyptic, hard science fiction, and others . . . Inventive and varied, the collection has a lot to offer for those seeking an interesting, entertaining, and thought-provoking read.” – Lisa Timpf, The Future Fire

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 473

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Also Available from Shadowpaw Press

shadowpawpress.com

Paths to the Stars

Twenty-Two Fantastical Tales of Imagination

One Lucky Devil

The First World War Memoirs of Sampson J. Goodfellow

Spirit Singer

Award-winning YA fantasy

The Shards of Excalibur Series

Five-book Aurora and Sunburst Award-nominated YA fantasy series

From the Street to the Stars

Andy Nebula: Interstellar Rock Star, Book 1

SHAPERS OF WORLDS

Science fiction and fantasy by authors featured on

the Aurora Award-winning podcast

The Worldshapers

Published by

Shadowpaw Press

Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

www.shadowpawpress.com

Copyright © 2020 by Edward Willett

All rights reserved

All characters and events in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead is coincidental.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions of this book, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted material.

Kickstarter Edition Printing September 2020

First Printing October 2020

Commercial trade paperback edition produced with the generous support of

Print ISBN: 978-1-989398-06-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-989398-08-1

Edited by Edward Willett

Cover art by Tithi Luadthong

Interior design by Shadowpaw Press

Created with Vellum

Copyrights

“Vision Quest” copyright © 2020 by Edward Willett

“Call to Arms” copyright © 2020 by Tanya Huff

“The Tale of the Wicked” copyright © 2009 by John Scalzi

“The Farships Fall to Nowhere” copyright © 2020 by John C. Wright

“Evanescence” copyright © 2020 by L.E. Modesitt, Jr.

“Peel” copyright © 2004 by Julie E. Czerneda

“The Knack of Flying” copyright © 2020 by Shelley Adina Bates

“Ghost Colours” copyright © 2015 by Derek Künsken

“One Million Lira” copyright © 2014 by Thoraiya Dyer

“Pod Dreams of Tuckertown” copyright © 2007 by Gareth L. Powell

“In Silent Streams, Where Once the Summer Shone” copyright © 2020 by Seanan McGuire

“Welcome to the Legion of Six” copyright © 2019 by Fonda Lee

“Good Intentions” copyright © 2020 by Christopher Ruocchio

“Shhhh . . .” copyright © 1988 by David Brin

“The Greatest of These Is Hope” copyright © 2020 by D. J. Butler

“A Thing of Beauty” copyright © 2011 by Dr. Charles E. Gannon

“Home is Where the Heart Is” copyright © 2020 by David Weber

“Tricentennial” copyright © 1977 by Joe Haldeman

Contents

Introduction

By Edward Willett

Vision Quest

By Edward Willett

Call to Arms

By Tanya Huff

The Tale of the Wicked

By John Scalzi

The Farships Fall to Nowhere

By John C. Wright

Evanescence

By L.E. Modesitt, Jr.

Peel

By Julie E. Czerneda

The Knack of Flying

By Shelley Adina

Ghost Colours

By Derek Künsken

One Million Lira

By Thoraiya Dyer

Pod Dreams of Tuckertown

By Gareth L. Powell

In Silent Streams, Where Once the Summer Shone

By Seanan McGuire

Welcome to the Legion of Six

By Fonda Lee

Good Intentions

By Christopher Ruocchio

“Shhhh . . .”

By David Brin

The Greatest of These Is Hope

By D.J. Butler

A Thing of Beauty

By Dr. Charles E. Gannon

Home Is Where the Heart Is

By David Weber

Tricentennial

By Joe Haldeman

About the Authors

Acknowledgements

Introduction

By Edward Willett

Like most writers of science fiction and fantasy, I started out as a reader. In our public library in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, every science fiction and fantasy book bore a bright-yellow sticker on the spine, featuring a stylized atom with a rocketship for a nucleus. I methodically worked my way along the shelves until I’d read most of the books thus marked, which included, not just novels, but short-story collections, some by one author, many by multiple authors; some offering original fiction, others reprints.

Inspired (or possibly corrupted) by my reading, I tried my own hand at writing science fiction when I was eleven years old, producing my first complete short story: “Kastra Glazz, Hypership Test Pilot.” My course was clearly set: I’ve been writing science fiction and fantasy ever since.

But while I could imagine myself as a writer, it never once occurred to me I might one day be editing and publishing a short-story anthology myself. And even had that thought crossed my mind, I would never have dreamed that within such an anthology I might have stories by authors of the caliber collected herein. Had you told me when I was reading Forever War as a teenager, for example, that someday I would not only meet and interview Joe Haldeman but I’d be republishing a Hugo Award-winning story of his, I wouldn’t have believed it. Joe Haldeman and the other authors I read then seemed Olympians to me, forever out of my reach.

Years went by. I had a few short stories of my own published and, eventually, novels. I even made it to a few science fiction conventions, something else that had seemed out of reach as a small-town prairie boy. I started meeting some of the Olympians. Sometimes, I was on panels with them, or I’d go out to dinner with them, or we’d have drinks in the bar. I realized they were not, in fact, unapproachable.

Fast-forward (through a whole bunch of writing and publishing adventures) to the summer of 2018, when the idea came to me to leverage my experience as an erstwhile newspaper reporter and radio and TV host, and the contacts I had made in the genre, to launch a new podcast, focusing on something I love to talk about: the creative process of crafting science fiction and fantasy.

I researched the making of podcasts, decided on a hosting service, set up a website, got the necessary software and equipment, and then reached out to possible guests—and was thrilled by how many fabulous authors said, “Sure, I’ll talk to you.” That willingness spanned the writing-career spectrum from legends of the field and international bestsellers to folks who are just getting started, from writers for adults to writers for young adults and children, from hard SF writers to writers of epic fantasy. The Worldshapers podcast took off with a bang—and, of course, continues.

Fast-forward again. In April 2019, at the annual meeting of SaskBooks, the association of Saskatchewan publishers of which I’m a member by virtue of owning Shadowpaw Press, a guest speaker talked about her success at Kickstarting anthologies.

Hey, I thought. I know some authors . . .

And thus, this book was born. I spun my wheels a bit at first—I’d never tried a Kickstarter and the challenges seemed daunting, and, of course, I had other writing and publishing commitments. But I garnered great advice from my fellow DAW Books author Joshua Palmatier, who has successfully Kickstarted numerous anthologies through his company, Zombies Need Brains, LLC, and more great advice from my fellow Saskatchewan author Arthur Slade, who has successfully Kickstarted a graphic novel, and, of course, it’s not like there’s a shortage of advice online (too much, maybe, since some of it is contradictory). At any rate, in the end, I screwed my courage to the sticking-place, rolled up my metaphorical shirtsleeves, and set to it.

I reached out to my first-year guests (an arbitrary decision to keep the length manageable—but don’t worry; I totally plan to do a Volume II with the fabulous guests from the second year) and asked if they’d be interested in contributing either an original story or a reprint. Many were. (Those who couldn’t, due to other commitments, were still highly supportive of the idea.) Many of the contributors, in turn, were very generous in providing backers’ rewards. I built the campaign. It ran over the month of March 2020.

Wait. Something else happened in March 2020. I can’t quite put my finger on it . . . it’ll come to me . . .

Yes, I managed to launch my first-ever Kickstarter campaign concurrent with the start of the worldwide pandemic’s North American tour. Lockdowns, people out of work, fear of what the future would hold . . . not particularly conducive to shelling out money for a collection of science fiction and fantasy, I feared.

And yet . . . people did. I’d aimed for $13,500 Canadian and ended up at $15,700. The book was a go. The stories came in. And now they’re going out again—to you.

Compiling and editing this anthology has been a complete joy. Every author has been a delight to work with. I hope you’ll find the stories, both originals and reprints, as much a pleasure to read as I have.

This is not a themed anthology in the way many anthologies are, but it does have a theme. It’s right there in the title: Shapers of Worlds.

Like potters shaping bowls from clay, authors shape their stories using a myriad of malleable elements: their own experiences, their hopes and fears and loves and hates, and their knowledge of history and science and human nature, all richly glazed with imagination and fired in the kiln of literary talent.

Each story in this book is set in a unique world shaped by a master of the craft. All of them showcase the skill of their creators.

Welcome, traveller, to the realm of The Worldshapers.

Enter, and enjoy.

Edward Willett

Regina, Saskatchewan

August 2020

Vision Quest

By Edward Willett

She comes, as so many have before her, in the twilight of the solstice, as this system’s primary slips beneath the northwestern horizon for a brief respite before lighting the sky again in the early morning.

She comes on a mechanical conveyance with two wheels, which she drives with thrusts of her legs, her feet on pedals. Some have come on horseback. Most have been on foot.

She comes to the edge of the small, round depression in the vast plain where I reside, a hollow with a pond at its centre, surrounded by the vegetation her people call cottonwoods and willows. That pond, dark and still, never goes dry, no matter how sere the fields surrounding it, no matter if the skies turn black with topsoil born aloft by howling winds, as they have so many times since I came here.

She hesitates at the rim of the depression, dropping her transportation device to the ground beside her. She is young, of course, as the people of this world count youth. They are all young, those who come here, drawn to me when they are growing and changing, metamorphosing from child to adult as surely as a caterpillar becomes a butterfly: a process I have examined in detail during my long sojourn, a process that I, in my own way, am also undergoing. For I, too, am young, as my kind count youth, though ancient indeed to her and hers.

This land in which I sojourn is gripped in a gauntlet of frozen iron for almost half of every revolution around this world’s star. Temperatures plunge, water turns hard as stone, and howling winds drive snow in long, hissing snake-forms across the ground. During those short days and endless nights, it seems nothing will ever grow again . . . and yet, every spring, it does. Green shoots rise from black dirt, leaves burst from buds on trees, insects hatch, mammals emerge from the burrows that honeycomb the earth around my hollow . . .

. . . and young humans, like the one who has come to me now, emerge from their own childish cocoons, look at the world around them with wide, new, questioning eyes, and begin to spread their wings.

She steps down into the hollow, following the path that leads to the edge of the pond and the smooth, shining rock that stands there, the path so many have followed before.

In buckskin or homespun, blue jeans or shorts, barefoot or booted, sandaled or sneakered—all words I have learned from them—they have come.

They come for the same reason I came here, long before the first of them appeared . . . and they come because I call them.

She is by the pond now. She looks down into it. It is dark, as dark as space, as smooth as ice, though it is not frozen, does not freeze even in the dead of winter, for it is not water.

And then she turns to face the polished stone. She hesitates, but then, in response to my unspoken call, places her hands upon it . . .

. . . and I am her.

Jamie stared at the strange black stone. She’d never seen anything like it on the prairie. It looked more like the kind of pedestal she’d seen sculptures on at the art galleries in Regina and Saskatoon her mom used to take her to.

What’s something like that doing out here? she wondered. And then, What am I doing out here?

She hadn’t known this place existed until she’d crested the slope she had just descended. But she’d known what it was the moment she saw it: a prairie pothole, a shallow depression left behind ten thousand years ago as the glaciers covering Saskatchewan melted away. She’d learned about prairie potholes in Mr. Gregorash’s Grade 8 geography class, last school year. She and her friends had found it hilarious that the prairie surrounding their little town was just as full of potholes as the thinly paved secondary road that ran to the highway, thirty kilometres away.

There were tens of thousands of prairie potholes like this one, and she’d never given them much thought, except maybe for Swallow Hollow, where the older kids sneaked off for parties in the summer. She was too young to go out there . . .

. . . but not for much longer.

High school, she’d thought, staring down into the hollow, feeling a flutter in her chest. High school meant riding a bus over that bumpy, pothole-plagued road to the highway, and then another twenty kilometres to the next town, a bigger one than theirs (though not by much). High school meant strange kids she’d never met before, and more homework, and . . . and all kinds of things she wasn’t sure she was ready for.

Last night, she’d dreamed about it, and the dream had turned into a nightmare. She’d been in the high school cafeteria, and then suddenly she was naked and everyone was laughing at her, and she’d tried to run out, but all the doors were locked, and then all the other kids had turned into snarling coyotes, and they’d come leaping toward her, teeth bared . . .

. . . and she’d woken up, gasping and crying, and she’d waited for Mom to come and give her a hug and make everything all right, like when she was little, but Mom hadn’t come, and then she’d remembered Mom would never come again, that cancer had made it so she’d never come again, and that Dad sat alone and drank in the dark before he went to bed, and then slept so hard he’d never hear her, even if she called out for him . . .

. . . and it was then, right then, in the midst of that middle-of-the-night fear and grief and longing, that she’d felt . . . a tug.

There’s a place, a voice seemed to whisper to her. A place you need to come to.

She’d gotten on her bike after lunch and ridden at least ten kilometres along the dusty grid road, the hot sun beating down on her shoulders, her route straight as an arrow except for the correction line just outside town. As she’d reached the abandoned Johnson farm, with its crumbling stone barn and tumbling-down house, the tug had come again. This way, it told her.

She’d turned off the gravel of the grid road just south of the farmhouse to ride along a rutted, seldom-used dirt path through barren fields, white with alkali, growing nothing but weeds. Grasshoppers leaped away from her bike in panicked profusion, sometimes bouncing off her chest and arms and face.

In all that time, she’d never had the slightest doubt about what she was doing, never once even considered disobeying that subtle inner summons.

She’d dropped her bike at the top of the path that led down into the pothole, and now, here she was, in the middle of the prairie, kilometres from town, standing in front of a mysterious black stone beside a strange black pool.

Alone.

Touch it, came that strange inner urge. Touch it.

She remembered something else Mr. Gregorash had talked about, the “vision quests” common to indigenous cultures across North America, including the Plains Cree who had once hunted buffalo on the very land Jamie’s Scottish ancestors had settled after the building of the Canadian Pacific railway.

“Although the details differ from culture to culture,” Mr. Gregorash had said, “in general, vision quests are a rite of passage through which young boys transition from childhood to adulthood. The boys purify themselves, in whatever fashion their tradition requires, then go to some isolated place in the wilderness to fast and meditate. They experience sacred, secret visions, believed to be a gift from their creator and ancestors, and discover their guiding spirit.”

Jamie wasn’t a boy, she had no First Nations ancestry, and she hadn’t purified herself, other than taking a shower the night before. Yet . . . here she was, alone in the wilderness (well, kind of, she thought; high above, a jet contrail cut through the cloudless blue), and something was telling her to touch this weird black stone.

Maybe it’s my guiding spirit, she thought. Are you there, God?It’s me, Jamie.

But if God, or any other spirit or spirits, was there, he or she or it or they didn’t answer, and if her ancestors had anything to say, they kept it to themselves. Staunch Presbyterians all, they were probably glaring down at her from heaven, lips pressed tightly together in disapproval.

The image made her mouth quirk with amusement. This is silly. You’re being silly. Just being out here is silly. Touch it and get it over with. Nothing will happen. And it’s going to be getting dark by the time you get home, and Dad . . .

She felt a flash of resentment. Her father would be mad at her. He’d probably yell. It seemed like he was always yelling at her these days, like they were always arguing.

It was that moment of anger, as much as the strange, inner urging, that drove her, at last, to not just touch the stone, but to slap her palms against it in irritation.

And then her body faded from her consciousness as her mind opened.

Where once I was one, now I am two.

As I have been before.

As I will be again.

I grow up with Jamie in her small town, play with her friends and her dog, feel the warmth and love of her parents, her wonder and joy at the world around her, seen through her innocent eyes.

Jamie grows up with me, admiring this system’s yellow star after its life-giving radiation, sleeting through my family’s vessel, woke my progenitors from their long dormancy and caused them to make me. She rides with me and my family as we plunge closer and closer to the star and the one blue, wet, living planet our sensors reveal. With me, she spends many cycles on the surface of our long, slender craft of meteoric stone and iron. Together, we are purified by vacuum and washed clean by the solar wind; then we share many more cycles deep inside it, in cold and silence and darkness and solitude, meditating, preparing for the quest to come.

I am with Jamie when her mother calls her into the kitchen to tell her what she has just learned from the doctor. I am with her as her mother fights through chemotherapy, recovers for a time, and then withers away, collapsing in on herself until, one dreadful night, she is no more. I am with her as she and her father stand hand in hand at the graveside, and she feels her father’s silent sobs shake his body, and she knows that nothing will ever be the same again.

She is with me for my launch, a birth of sorts, not as messy as a human birth, but the same sudden emergence from darkness into light, the same separation from safety, the same sudden thrust into the unknown. Aflame, Jamie and I plunge together from orbit. Smoking and steaming, we bury ourselves in the land. Together, we draw that land around us, mimicking the natural features, crafting a disguise, a camouflage, what a human hunter would call a blind.

And then, together, we reach out. We call, we summon, we urge. We bring the brief-lived dominant sapients of this strange world to us, our minds able to touch theirs only in the spring of their lives, as they move from childhood to adulthood.

And when they come, we merge with them, as I have merged with Jamie, as I have merged with so many before.

With Jamie, I wake from the frightening dream, wishing for Mom. With Jamie, I feel the call . . . my call . . . to ride into the prairie, to a place she has never seen, had no clue existed, but which now feels to her like the most important place in the world, the place she must go to, above all else.

With Jamie, I leave my bike at the top of the hill, walk down into the depression where the dark pond waits, and touch the smooth black stone.

Where once I was one, now I am two . . .

I am not the creator, and I am no one’s ancestor, and I am not a spirit, and yet I give to Jamie, as she gives to me, visions sacred in the only way anything is truly sacred: sacred because we, who live and think and fight the universe’s uncaring entropy, who give to it the only meaning it has, imbue them with sacredness.

Only seconds in real time after Jamie touched the interface, I sever the connection.

Where once I was two, now I am one.

Jamie stepped back from the stone. Her hands tingled, but that was all.

Or was it?

She frowned. Something swirled on the edges of her memories, strange, dream-like images of stars and moons and planets and fire, and even stranger images of boys and girls close to her own age, dressed a thousand different ways, standing where she stood now, touching the stone as she had, and, just like her . . .

. . . just like her . . .

. . . just . . . like . . . her . . .

. . . what?

The memories faded, ghosting out like the afterimage of a photoflash.

Jamie looked at the stone again. She had no desire to touch it. It was, after all, just a stone.

She looked down into the dark pool, so smooth, so black, like a night sky devoid of stars. For a moment, just a moment, she had the feeling the pool was looking back at her.

She took an involuntary step away from it, feeling a little shiver of fear. Don’t be stupid, she chided herself. You’re not a little kid anymore. She forced herself to step closer again. Then, on a whim, she reached down, picked up a pebble, and tossed it into the water. It splashed the same as any other water in any other pond, the ripples spreading smoothly out in concentric circles to the banks. See? It’s just a pond. She remembered her earlier fears about starting high school. And high school is just school. I’ll be fine.

She glanced up at the sky. I’d better get back. There’s still a lot of light left. If I’m lucky, I might make it before Dad notices how late I am. I don’t want him to worry. She felt a sudden surge of love and concern for her father. It’s just the two of us now. I have to look after him.

She hurried up the slope to her bike, mounted, and rode off through clouds of grasshoppers and alkali dust without a backward look, following the dirt road toward the ruined farm in the distance, the grid road beyond, and home.

I watch Jamie for as long as my sensors permit, her bare legs flashing as she pumps the pedals of what I now know she calls a bicycle, and silently wish her well.

She will remember nothing of me, or of this place. Her memories of her childhood will never contain even the faintest trace of my memories of mine, or the memories of all the other young humans who have come to me through the centuries, though we shared them so deeply while we were one.

Nor will she remember the memories that are not mine, the memories of my race, the memories my progenitors folded into my surface as I was being made: the glimmer of starshine on methane seas, the glow of rings slashing through the dark sky above the towering storm clouds of a gas giant, twin suns locked in an intricate gravitational dance, light gasping its last in a seething maelstrom of radiation as it plunges into a black hole, all the wonders of the universe my race has explored since before Earth cooled enough for liquid water to fall and begin the long, slow filling of the oceans, the first step toward life, and intelligence, and girls like Jamie.

And yet, though she will never remember me, through me she has made a connection with her world and her universe that will give her a sense of peace and purpose. It is a connection that will guide and ground and steady her through the tumultuous years to come, through the entirety of her too-brief walk upon this planet, as it has so many young humans before her, the countless boys and girls who have found me in the millennia I have rested here.

She will not remember me, but I will remember her, as I remember all the others. I will still remember her centuries from now when, at last, my vision quest comes to a close, when my progenitors swing by this planet again and pull me into their warm and welcoming embrace, to join with them, to share my visions, to add to my race’s memories, to strengthen and enrich all of us with what I have learned from those who live and die upon this blue-green speck.

I came here as a child. I will return to my family as an adult. The young ones I have met here on this great flat plain flicker for only an instant, a brief spark of light in the darkness, but that bright flash will be remembered for as long as my race sails the universe in our slender ships of stone and iron, the warmth and yearning and love I have found within their young souls refreshing our ancient ones forever.

The solstice sun has set upon the plains of Saskatchewan.

Spring has ended.

Let summer begin.

Call to Arms

By Tanya Huff

“Mirian! There’s an Imperial Courier waiting for you in the market square!”

Mirian held out a hand to keep Dusty from toppling over, so fast was his change from fur to skin. “On a horse?” Not everyone in Harar—Orin’s largest settlement—was Pack, but this was the old country, and the population skewed to fur. Convincing a horse not bred in Orin to enter Harar was next to impossible.

“No, on foot.” His lips were drawn so far off his teeth, Mirian barely understood him. “She wants you. Why does the Empire want you?”

“I expect it’s not the entire Empire.” When Dusty continued snarling, she sighed. “So, tell her where I am.”

“Can’t. Otto wants you to come to her. Suspicious, power-tripping, mangy . . .”

“Dusty.” Mirian was Alpha of her own small pack, but they lived in Harar at the Pack Leader’s sufferance. Otto, new enough to the position of Pack Leader the scars on his shoulder were pink, was still testing his authority. Still checking to make sure Mirian would continue to follow the rules. To be fair, she didn’t blame him. Rolling up onto her feet, she brushed dirt off her hands. “Tell him I’m on my way, but I need to clean up a bit first.”

“Because you won’t come running when the Empire snaps its fingers!”

“Because I’ve been gardening. And I haven’t lost all the manners my mother worked so hard to instill. Go.”

His ears were back in protest when he changed, but he turned and headed back toward the centre of the settlement.

Mirian watched him run. Other than the gleaming silver fur that marked the torture he’d endured as a child, he was, like everything else in her world, multiple shades of grey. He’d grown into a teenager in the nine years since she’d taken him and the rest of her pack out of the Empire. In skin, he was taller than the others his age, arms and legs and torso given length by the castration he’d suffered under Leopold's knife. His face still held boyish curves and probably always would. In fur, he was large without bulk, and faster than everyone he’d ever raced against. In time, Mirian could see him becoming the Pack Leader’s top runner—once he worked his way through his current teenage rebellion.

“Provided I don’t strangle him before he manages it,” she muttered. She shifted the dirt on her skin back to the ground, and stepped up onto the wind.

Tucked out of sight in the alley by the cheese shop, Dusty glared at the courier who stood by the well talking to Otto. The Empire of memory smelled of blood and death. The courier smelled of sweat and long days on the road without a chance to change or bathe in anything but cold water. She was tall and athletic, probably ex-military. As Dusty understood it, a lot of couriers were, and that would explain the rifle leaning against her pack. She didn’t look dangerous, but Dusty was well aware looks meant nothing. He didn’t look dangerous. But he was.

“Hey!”

Jerked out of his thoughts, Dusty started as Alver waved a hand in front of his nose.

“I called you like six times.” The young mage crossed his arms, half a dozen white flecks drifting across the dark brown of his eyes. “What’s up? Does she smell so fascinating you think you can ignore me?”

Dusty shouldered him hard enough to nearly knock him over and changed. “That’s an Imperial Courier!”

“Well, that explains the uniform.” Alver threw a kilt at his head. “Here. Unless you planned on waving your bare ass at her.”

“The Empire slaughtered most of my family, then hacked off my father’s leg, locked him into a silver collar, and threw me in a cell with him as he bled to death.” He yanked the kilt straps through the double buckles and waved a hand below his waist. “And this.”

Sean Reiter thought the emperor had him castrated so he could be raised as a pet. “Or because he was a sadistic, insane, murdering son of a syphilitic hog,” Sean had amended dryly. “Could be either. Probably both.”

Alver frowned. “Well, yeah, but she didn’t do it.”

“She’s Empire!”

“So?” Alver bounced his shoulder off Dusty’s. “And stop growling at me. If she tries anything Imperial, I’m sure the Pack Leader will let you rip her throat out.”

“Mirian won’t.” Mirian didn’t understand.

“If she gives you so much as a dirty look, Mirian will turn her inside-out. You know that.” Alver shrugged. “She’s your mom, or as good as. And she’s your Alpha.”

“I’m nearly sixteen . . .”

“So am I, and my mom still licks my ears. What can you do? I mean, someday I’ll have to . . .”

Dusty raised a hand to cut him off, face turned into the breeze. “Mirian’s coming.”

He expected Mirian to ride the wind into the market square, bring a gust strong enough to throw the Imperial—and maybe Otto—back on their heels, but she walked in like a normal person, Tomas in skin, fully dressed, at her side.

From what Dusty could see of her expression, the Imperial Courier had also been expecting a more mage-like entrance. Not a medium-sized twenty-seven-year-old in a faded green dress. Her hair was up, and she’d even put on shoes, although most of Harar didn’t bother in the summer.

“It’s like she’s playing dress-up,” Alver murmured. “Pretending she’s not a throwback to the kind of ancient mage who could destroy the world. Lulling them into a false sense of security. Also,” he added after a moment, “that dress is at least five years out of style.”

“No one cares about the dress,” Dusty growled.

Alver sighed. “Obviously.”

The courier recovered quickly. She stepped past Otto and tipped her head to Mirian. A sort of bow, Dusty realized, not submission. “Your Wisdom. If we could speak privately?”

“No.” Otto inserted himself between the two women. “Anything the Empire has to say will be said publicly.”

Tomas’s lips lifted off his teeth.

Leaning against the corner of the cheese shop, Alver shook his head. “Tomas needs to be careful with those almost-challenges or Mirian’s going to lose her Beta.”

“Tomas can take him.” Tomas had been part of the Scout Pack in the Aydori army.

Alver snorted. “That’s what I said.”

Dusty elbowed him to shut him up.

Over by the well, Mirian had given Otto a long, assessing look. Otto met it until Mirian’s lips twitched and she looked away. “Here is fine,” she said, gesturing for the courier to begin.

“As you wish, Your Wisdom.”

“Clever.” Alver nodded, as though his opinion meant something. “She’s acknowledging the decision was Mirian’s, not Otto’s.”

“Alver, shut up. I need to hear this.”

As though someone had heard him—and given the Mage-Pack scattered through the gathering crowd, Dusty wasn’t ruling it out—a breeze came up and the courier’s voice filled the market square.

“I BRING WORD FROM LORD GOVERNOR . . .” Eyes wide behind the lenses of her glasses, she stared around the square.

“Apologies,” called a voice from the crowd. “That was a little loud. I’ll dial it back.”

Tomas laughed and leaned in toward Mirian. Dusty couldn’t hear what he said, but Mirian laughed with him.

“Probably reminding her of that time she nearly deafened the lot of us.”

“We were seven,” Dusty snapped.

“But I remember. Look . . .” Alver waved at the courier, who was visibly pulling herself together. “She didn’t expect basic mage-craft. You know what that tells us? Mages are still thin on the ground in the Empire.”

“Comes from murdering them.”

“Probably.”

The courier took a visibly deep breath and began again. “I bring word from Lord Governor Marchand of the Imperial province of Bienotte. Over the last few years, the Krestonian Empire has raised the taxes paid by Bienotte again and again. The people of Bienotte struggle to survive. Lord Governor Marchand has had enough. He won’t watch his people starve. Will you help him throw the heavy yoke of the Empire off his people? Will you help lead them to independence?”

Mirian cocked her head—and blinked eyes white from rim to rim. When Dusty was younger, he’d thought she could see the truth. He wasn’t entirely convinced she couldn’t. After a long moment, she smiled and said, “No.”

“But he wants to free his people from the heavy yoke of the Empire! Lead them to independence!” Hands in the air, Dusty stomped across the common room and back, bare feet slapping against the floor. “You should be all over that!”

Distracted by the silver lines of anger trailing in Dusty’s wake, it took Mirian a moment to ask, “Why?”

“Why?” His lips drew back off his teeth. “Maybe because of Nine! And Bryan and Dillyn! Matt and Jace! Jared and Karl! Maybe because of Stephen! They killed him, even if it took him a couple of years to die! Maybe because of me and my dad and all the other Pack they murdered! Maybe because of that!”

“Dusty, I understand that you feel . . .”

“No, you don’t!” He took a deep breath. “You can’t! They have to pay for what they did.”

Mirian tried to find the words that would push past Dusty’s anger. “This is a different government. Imperial Packs are treated as equals under the law . . .” She kept talking over his protest. “. . . and when they aren’t, because laws and prejudices don’t always walk in step, the wind brings the news and I deal with it. You know that.” It had happened less and less as the years passed. Mirian hoped it was because people defaulted to doing the right thing when not egged on by a corrupt government. Tomas insisted it was because she’d removed enough bigoted assholes their numbers had dropped below critical mass.

“Then why won’t you help now?”

She shook her head. “Governor Marchand doesn’t want me to help. He wants me to be his weapon. He wants me to attack the Empire for him.”

“So?”

“If the governor—or anyone else—wants independence from the Empire, they have achieve it themselves.”

“That could take forever!” Anger tinted the air around his head and shoulders. “You heard the courier, they’re starving now!”

“If Governor Marchand had asked for food . . .”

“They asked for freedom. You need to free his people from the Empire!”

“I do?”

“Yes!”

“Then they’d be mine.”

“Mirian!”

She waved a hand at the clutter. They’d already expanded twice, when first Matt, and then Karl, were married. “Where would I put them?” Beside her, Tomas’s tongue lolled out, and she buried a hand in his ruff. “Dusty, you have to . . .”

“No, I don’t,” he snarled, changed, and charged out of the room. The screen door slammed behind him.

In the next room, Karl and Julianna’s twins screamed their objection to the sudden noise, their distress pulsing through the house.

Mirian sighed. “That went well.”

Tomas’s nostrils flared as he glanced around the dining-room table. “Where’s Dusty?”

“He’s gone up to the summer pastures with Alver’s family.” Mirian motioned him into his chair and pushed the platter of rare beef toward him, using her elbow to keep Dillyn from grabbing seconds before everyone had firsts. Her mother would be appalled at the chaos and even more appalled at her belief that the sturdy harvest table and mismatched chairs belonged in a dining room.

“He’s that angry with you?”

“He’ll get over it,” Nine growled before Mirian could answer. “The Empire can rot from within without our Alpha’s help.”

Dusty pushed his shoulder up against Alver’s side and pushed a branch out of the way with his muzzle. Firelight reflecting on her glasses, the courier reached for another piece of wood, paused, frowned, and said, “You might as well come out. I know you’re there.”

Alver, who had no sense of self-preservation at all, stepped into the circle of light before Dusty could stop him. “How?” he demanded.

She smiled, although she didn’t relax. “You smell of sandalwood.”

“I do?” He turned his head, sniffed the shoulder of his jacket, then half-turned to meet Dusty’s gaze. “You might have mentioned that. Now, are you coming out or not? This was your idea.” He mimicked Dusty’s voice. “I’ll tell my family I’m going to the summer pastures with you, and you tell your family Mirian asked you to stay in Harar to work on your mage-craft. We’ll catch up to the courier and go with her to help Governor Marchand defeat the Empire.”

It had also been Dusty’s idea to watch the courier for a while before joining her, but Alver only listened to what he wanted to hear. And he didn’t want to hear that the scents he loved so much gave him away to anyone with a nose. Dusty huffed out a breath, tucked his tail close to keep it from being caught in the brambles, and walked out to stand by Alver’s side.

“Well, hello.” Her smile broadened. “Aren’t you a big . . .” And her smile disappeared. “You’re not a dog, are you?”

“Told you she was clever,” Alver muttered.

Dusty stepped behind Alver, shrugged out of his pack, and changed. Skin or fur, Pack didn’t care and it never used to matter who saw his scars, but he’d been a child then and he wasn’t now. Yanking out his kilt, he cinched it around his waist before stepping back into sight. “I’m Dusty, this is Alver. He’s a mage. We’re coming with you to help fight the Empire.”

“Are you?” The question was polite, if a little aloof. She hadn’t reached for the rifle leaning against the log beside her, so Dusty figured aloof was fine. After a long moment, she nodded. A strand of long, light-brown hair, loose from her braid, fell forward over her shoulder. “Nina,” she said, tucked the hair back behind her ear, and added, “Have a seat.”

“Don’t mind if I do.” Alver drew up a hummock of earth and sat.

The aloofness disappeared. Dusty figured Nina was about the same age as Alver’s mother, but her sudden enthusiasm made her look younger. “You’re an Earth Mage!”

“Nope. We don’t do that divide and conquer stuff. I’m just a mage.”

“Like Mirian Maylin!”

“Yeah, I’m . . .”

“No, you’re not.” Dusty crossed his ankles and dropped to the ground. “No one’s like Mirian. Mirian could rule the world if she wanted. She can do anything. She could leave home as we get to Beinotte and still beat us to the governor’s house.”

Alver poked him. “I thought you were mad at her?”

Oh yeah. He dug his fingers into the ground. She was fine allowing the Empire to . . . well, to be the Empire. Still . . . “Facts are facts.” He looked up to find Nina leaning slightly toward him, the force of her attention almost Pack-like.

After a moment, she sat back. “You’re one of the Ghost Pack. The child she rescued.”

“Oozes clever,” Alver muttered as Dusty snapped, “I’m not a child!”

“No, you’re not. My apologies if I implied otherwise.” She raised both hands and left them raised until Dusty nodded, then she picked up a tin mug from a rock by the fire. Her hands engulfed it completely as she raised it to her mouth to drink.

It smelled like the coffee Sean brought for Mirian from Aydori, where it was both hard to get and expensive. Probably cheap and common in the Empire because they’d just conquer and murder until they found a steady supply. He was impressed that Nina had managed to carry enough to get her to Harar and home.

“I should send you back,” she said, once she’d swallowed and set the mug down.

Alver snorted. “Like we’d go.”

“There’s that,” she acknowledged.

Later, lying across the fire from Nina, Dusty breathed in Alver’s familiar scent, laid his head on his paws, and dreamed of ripping the Empire into small bloody pieces.

“Seriously? They really believe the Pack are all male and the Mage Pack are all female? That’s crack-brained.” Dusty could hear the frown in Alver’s voice.

And the shrug in Nina’s. “No knows much about the packs in the Empire.”

“Yeah, I’m surprised.” Alver was breathing a little heavily, keeping up to Nina’s quick, purposeful stride, and Dusty figured if he hadn’t been getting an assist from his earth-craft he’d have had to ask her to slow down. “Maybe because you had them declared abomination, then tortured and killed them. I mean, not you, but . . .”

“I know what you mean. That’s one of the reasons why Lord Governor Marchand wants to break up the Empire.” She stepped over a fallen tree and pushed her glasses back up into place with her right index finger. “No one should have the kind of power it takes to lead their people down such a dark path.”

“Mirian says a little power applied at the right place is more effective than calling out the army.”

“Does she?”

“Yeah, and she says . . .”

Dusty broke into a run. He didn’t want to hear Alver and Nina discuss Mirian’s philosophy of power. Not when she had her head stuck so far up her own mage-craft she refused to help.

“Wait.” Nina came to a sudden stop and turned until she could look up at the higher rock ledge where Alver balanced. “Are you saying your mage-craft is first level?”

He shrugged. “I’m fifteen. What did you expect?”

“I don’t . . .” She fell silent, frowned, and finally said, “I know nothing of mage-craft, I thought . . .” Another silence. A deeper frown. “You’re kids. I don’t know what I was thinking. I should take you back.”

“Okay, first, you already established that you can’t take us anywhere we don’t want to go. One of us, maybe,” he allowed after a moment. “But not both of us. And second, Mirian only had first levels when she rescued the Ghost Pack.”

Nina shook her head. “I suspect it was more complicated than that.”

Alver glanced down, shifted a bit of loose rock out of his way, and jumped. “Mirian says it wasn’t.”

Waiting at the bottom of the path, Dusty changed long enough to snarl, “Talk about something else!”

Dusty didn’t change in front of Nina, always finding something he could put between them—Alver, if nothing else was available. He forgot that anyone who knew dogs could tell what had been done to him.

“Was it the Empire?” she asked one night, pitching her voice to keep from waking Alver.

He snorted and laid his head on his paws. Who else would it have been?

“Then I can certainly understand why you want to help us be free of them.”

If she could, why couldn’t Mirian?

“You’d have to be trying to starve in the woods at this time of the year.”

Crouched by the firepit, Nina nodded. “I restocked in Harar, but it helps to have a hunter with you.”

“And a mage,” Alver pointed out as he showed Nina the berries in the fold of his shirt.

Dusty spat a bit of rabbit fur out of his mouth. “Bloody balls, Alver, it’s not all about you!”

“Language,” Alver chided around a mouthful of crushed fruit.

On those rare occasions Nina laughed, she laughed with her whole body. Dusty liked that about her.

“Where does your tail go?”

Dusty looked over at Alver and they both snickered.

“What?” Nina demanded. “Is it a Pack secret?”

“Not a secret, it’s like the first question kids ask.” Dusty pitched his voice higher. “Where’s my tail gone?”

Nina spread her hands. “Well?”

“It just . . . goes.”

Mirian stepped out of the chicken coop, wiping her hands on her apron—realizing as callouses caught that her mother would be appalled at the condition of her skin. “Servant’s hands,” she’d declare with a sniff and insist she soak in vinegar until the callouses were soft enough to buff away. Her mother’s opinion of her lack of servants was revisited in every letter received. “Tomas Hagen deserves better than a cook and a daily. It’s like you’ve forgotten everything I ever taught you!”

Not everything, but she was working on it.

“Mirian!” Amelie, Alver’s oldest sister, waved from the path, her pale hair almost-but-not-quite silver among the shades of grey. “Mother sent Jonas and me down to pick up a few things,” she said as Mirian drew closer, “so I thought I’d drop in and make sure Alver was behaving himself.”

“Alver?”

“Alver. Might be a mage someday if he grows out of thinking he knows everything al . . .” She trailed off. “He’s not here, is he?”

“He isn’t.” A breeze lifted a loose strand of Mirian’s hair. “I assume Dusty isn’t with you.”

“He isn’t.” She sighed. “It’s been almost three weeks. They could be anywhere. Can you find them?”

“Oh, yes.” The breeze became a wind, although the leaves around them continued to droop in the summer heat. Mirian’s feet left the ground. “I can find them.”

“You need more clothing.”

Dusty looked down at his bare chest and legs. On any warm day, men dressed only in kilts walked barefoot on the streets of Harar. If Pack wanted access to fur, they didn’t want to waste half the day getting there.

“And shoes,” Nina continued. “Only the truly destitute go barefoot.

“Alver?”

Alver patted himself down as though there might be shoes hidden under his clothes. “Nope. No extras.”

“Fine.” Behind the coverage of a juniper, he dropped his kilt and changed. He could feel Nina’s steady gaze on him as he emerged, mouth full of fabric. After he spat the kilt at Alver’s feet, he sat and met her gaze.

“It might work,” she allowed after a moment. “You’re big, but we’re too far from Pack territory for anyone to assume you’re not a dog.”

“He does tricks,” Alver said brightly.

Dusty growled.

“Or not.”

Cities smelled horrible.

Alver was enjoying himself, pointing and peppering Nina with questions she patiently answered. Dusty fought the urge to nip him. They didn’t have a collar and he wouldn’t have worn it if they did, so he stayed close to Nina’s side. She kept them on backstreets as long as she could, where the thin children wanted to ride him . . .

“But he’s so big and fluffy!”

. . . and a man who smelled of sour wine followed the three of them for blocks making larger and larger offers until Nina turned and quietly told him the dog was not for sale. Dusty couldn’t see her expression—he was watching the man, hoping for an excuse to take him down—but it was definitely effective, eliciting a mumbled apology and a fast retreat.

Unfortunately, although Nina had explained they’d enter at the rear of the government building, they had to cross a main street to get there. Dusty had never seen so many horses in one place. And none of them were the sturdy mountain ponies who grew up surrounded by Pack.

“This isn’t going to be good.” Alver glanced both ways. He lifted his head into the wind, frowned, and sighed. “Oh, so much less than good. However, if we have to cross, we need to move quickly.”

“We have to cross.”

“All right then. Dusty, go! Wait for us on the other side.”

At the first break in traffic, he leapt forward. Wind, funnelled down the street by the five- and six-story buildings, ruffled his fur. Was that what Alver had meant by less than good? And why had they made the streets so wide?

Two, three, four horses let it be known they’d scented a predator.

He could feel the impact of iron-shod hooves against the cobblestones as they fought to be free of their traces.

Shouting, a collision, a scream . . .

Across the street and tucked around a corner in a shadow at the base of a building, he waited.

And waited.

He’d begun to worry, had stood and taken a step back out into the open, when his companions finally joined him.

Alver sagged against the building. “Well, that could have gone worse.”

“How?” Nina demanded. “It’s chaos out there. People were hurt! What happened?”

“What happened?” Alver stared at her for a long moment, white flecks drifting across his eyes. Then he sighed. “The Pack are apex predators.”

“That’s . . .”

“Apex,” he repeated. “Bears will back away from a fight with Pack. Be thankful Dusty moved so fast only a few horses scented him.”

The noise suggested more than a few horses were involved in the chaos, although everyone knew a fear reaction from one herd animal would set off the rest. So would the scent of blood. And Dusty could definitely smell blood.

Nina stared down at him as though she were seeing him for the first time. As though she could finally see the help they were offering. “We could use that reaction against mounted Imperial troops.” She reached out as if to stroke Dusty’s head, then let her hand fall back to her side. “You okay?”

Dusty pushed up against Alver’s leg. He’d been held and tortured by the Empire but Imperial horses had never harmed him, and yet, it was horses who were bleeding.

The government building was old, with thick stone walls, and wonderfully cool inside. It was also the largest building Dusty had ever seen—not counting the Imperial Palace where he’d only seen a cell, the tiled room where the knives were used, and the ruins Mirian had left it in. Nina ushered them into a small room and said, “Wait here. I need to inform Lord Governor Marchand I’ve returned.”

The scents in the room were old, and no one but a female rat scavenging for her young had been there for days, so once Nina left, Dusty changed. By the time she returned, he’d changed twice more and Alver had begun to speculate about the tiny sheep on the wallpaper.

“Lord Governor Marchand wants to see you immediately.” She tossed a bundle down onto the scarred tabletop. “I found you some clothes.”

“I have clothes,” Alver protested.

“You had clothes three weeks ago. Now you have stains held together with dirt. Change.”

The trousers, shirts, and vests fit surprisingly well, although Nina had to tie both their neckcloths. The shoes she’d found were a bit large. Dusty appreciated being able to move his toes, but Alver kicked his off. “I’m wearing my own. I’m a mage,” he added before Nina could protest. “I don’t care if the shoes don’t match the outfit.”

“Liar,” Dusty muttered, pulling the laces tight.

“We all should have bathed, but we don’t have time.” Nina had changed while she was gone and wore a courier’s tabard over clean clothes. An elderly man in a faded uniform stared as they stepped back out into the hall, then hurried away before they came close.

“What happened to him?” Alver asked, thumbs tucked into the pockets of his vest.

“Happened?”

“He had a split lip and a bruise on one cheek.”

“I’m a courier,” she sighed. “I’ve been gone for over six weeks, and the servants aren’t my responsibility when I’m here.”

“Maybe they should be,” Dusty growled. “He smelled of hunger.” He expected Nina to ask what hunger smelled like—her willingness to learn had been one of the things he liked best about her—but she merely frowned and kept walking. Keeping up kept him from looking around, but he’d have had to be moving a lot faster to have missed the scents of neglect.

When they stopped by an old, worn door, she twitched a wrinkle out of her tabard, took a deep breath, and led them into a large room. There were wide double doors and windows high in the long wall to his right, and a dais in the centre of the wall to his left. Centred on the dais was a sturdy chair with a high back and broad arms that wouldn’t have looked out of place in Harar. The man in the chair had steel-grey hair, cut even shorter than Pack hair, but his shoulders were still broad and square, and he wore the same uniform as the two-dozen soldiers who stood in ranks on either side of the dais. All of them carried the new rifled muskets. Sean had brought one the last time he’d come back from Aydori.

“You can fire them faster, aim them accurately, and while they’ve finally gone into mass production, they’re still stupidly expensive. It’d bankrupt a country if they tried outfitting their entire infantry with these things.”

“They’re not wearing the Imperial crest,” Alver muttered. “Those are bears, not ravens.”

“They want to free themselves from the Empire,” Dusty growled. “Because they’re not stupid.”

A bulky camera had been set up in the centre of the room, the photographer arguing with her assistants about . . . about angles, Dusty assumed, given the arm-waving. Teger, the Pack Leader before Otto, had a camera, but it was half the size.

Conversations stopped, and one by one the clusters of people standing by the walls turned to watch them cross the room.

“So, these are the children you brought me instead of the mage I sent you for.” Lord Marchand had a Pack Leader’s voice. Deep. Resonant. Confident.

Nina bowed. “They aren’t children, Your Lordship. Alver Goss is a white-flecked mage and Dustin Maylin is Pack. When Mirian Maylin refused to return with me, they offered their assistance.”

“Their assistance?” His brows rose. “And how exactly can they assist?” A few people snickered.

“Your Lordship . . .”

“Let them speak for themselves, Courier.”

“Sir.”

Lord Marchand beckoned them closer. “So, how can you assist me with the Empire?”

“I hate the Empire,” Dusty growled.

He shook his head. “Not what I asked you.”

No, it wasn’t. How could they assist? Wasn’t it obvious? “There’s no Pack or Mage-Pack in the Imperial armies.”

Dark brows rose. “And?”

The vest was hotter than fur. He tugged at the hem. “And that means we have an advantage because they don’t know how to defend against us.”

“An advantage? I don’t think so.” Lord Marchand stood and pointed at Dusty. “Silver.” Then at Alver. “Can you stop a bullet?”