Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

Being separate from the Scottish mainland, the Shetland Isles have a rich and unique tradition of folklore, from selkies to invading giants and Vikings. This book brings together many tales of the Isles, including The Boy Who Came from the Ground, and Norway's First Troll, among many others. This collection is sure to enthrall and entertain all, from for those who call the region home to anyone looking to experience the magic of Shetland for the first time. As a child, Lawrence Tulloch learned many folk tales from his father Tom, a tradition bearer whose folklore was collected by the School of Scottish Studies. As a storyteller, Lawrence collected even more tales and this book contains many favourites – some you may recognise, but with a Shetland twist.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 298

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

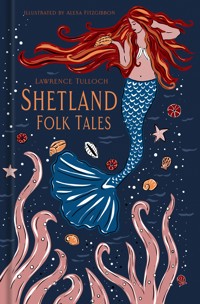

The wonderful illustrations in Shetland Folk Tales were created by Alexa Fitzgibbon. After first coming to Shetland from France in 2006 to study, Alexa spent the best part of the next seven years immersed in Shetland culture. Lawrence was the first person she met there, and it was the beginning of a solid friendship. Drawing ink illustrations throughout high school, she has kept up the passion alongside her love of photography.

First published 2014

This edition published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Lawrence Tulloch, 2014, 2025

The right of Lawrence Tulloch to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75095 546 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

The History Press proudly supports

www.treesforlife.org.uk

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 The Fetlar Finnman

2 The Netted Mermaid

3 The Laughing Merman

4 The Mermaid Who Loved a Fisherman

5 The Blacksmith and the Njuggel

6 Martha

7 The Seal on the Vee Skerries

8 Mallie and the Trow

9 The White Cat

10 The Raven

11 The Fiddler and the Cows

12 Tommy and the Wicked Witch

13 The Butter Stone

14 Witch Against Witch

15 A Spanish Ship Visits

16 The Fairy’s Wine Well

17 The Gloup Disaster

18 Flokki of the Ravens

19 The Cow Killers

20 The Marriage of Hughie Brown

21 The Half Gruney Lasses

22 Gibby Law

23 Sheep Thieves

24 The First Midges

25 Da Hallamas Mareel

26 Ursula

27 The Mouse and the Wren

28 Ruud

29 The Sad End of Grotti Finnie

30 The Cats and the Christening

31 Einar the Fowler

32 Erik and the Shark

33 The Boy That Came From the Ground

34 The Poisoned Sixpence

35 Black Eric of Fitful Head

36 The Eagle and the Child

37 The Minister’s Meeting

38 Singna Geo

39 The Death of James Smith

40 Sigmund of Gord

41 The Woman with the Red Hand

42 The Snuff Taker

43 The Three Yells

44 The Funeral Ghosts

45 The Skull

46 Norway’s First Troll

47 Midwife to the Trow

48 Katie Lottie

49 Kidnapped by the Trows

50 Feeding the Trows

51 Winyadepla

52 The Borrowed Boat

53 Christmas at Windhouse

54 Farkar’s Pig

55 In Aboot da Nite

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In compiling a book of stories it is not just the folk that you learned the stories from who have to be thanked. There are also the folk, long gone, who took the stories on during their lifetime.

My father, Tom Tulloch, was a major source of stories for me. He learned the stories from his mother and she got them from her father. Any storyteller will say much the same thing.

As well as the Henderson men, regular visitors to our house were Andrew Williamson from a house called The Brake. My Uncle Bobby from Brough told me about the sheep thief, Black Eric of Fitful Head.

When we lived in Gutcher, also in Yell, we were close to the ferry terminal and Jeemsie Laurenson from Fetlar never missed an opportunity of visiting when he was waiting for the ferry back home.

Jackie Renwick the poet and storyteller from Unst we saw several times a week when he was working in Yell. Although he was never a visitor to our house I had the privilege of hearing the great Brucie Henderson from Arisdale in Yell tell stories.

Gordon Walterson from Sandness is another who has given me stories. Charlie Laurenson from Voe is yet another. We used to go to meetings together and he was always at his best in a one to one.

Although he is no longer a young man, George P.S. Peterson from Papa Stour and Brae is still Shetland’s premier storyteller. He has a huge number of stories and he was a founder member of the Scottish Storytellers Forum.

Some of my best friends are fellow storytellers and they have made a big contribution to my store of stories: Hjörleifur Helgi Stefánsson from Iceland, I never see him often enough, and Ian Stephen from Lewis who has been my friend for many years.

Bob Pegg has invited me to many festivals and gatherings. He is a man with awesome talent and personality and it was he who suggested that I write this book. His own book, in this series, is superb.

I am an only child but there is one who I look on as a brother. He is Tom Muir from Orkney. Together we have clocked up thousands of miles on storytelling adventures. No man could ever be a better or more generous companion.

I greatly value the friendship and encouragement that I have received from Professor Bo Almqvist. He is from Sweden but he lives in Dublin. I regard him as the foremost authority on Nordic folklore and legends.

Thanks also to Northmavine men Peter Robertson and Ivor Johnson. Peter lent me some books and both of them have followed my progress and they have put me on the track of stories. I am grateful to The History Press and Declan Flynn for giving me this writing opportunity.

As always I am indebted to my family for the help and support they have given me. Margaret, my wife, has been with me every step of the way, as she is with all my endeavours. Without her this book would never have happened.

Our daughter, Liz, has been very involved in the writing of this book. Her computer skills, the time and patience she has given; it has been of the utmost help. She has also been my researcher and advisor. Just when I thought that something was impossible she would come up with the answer.

Last but not least I thank Alexa Fitzgibbon. Despite her name she is French and she came to Shetland, as a student, in 2006. Since then we have come to look on her as part of our family and, to me, she is like another daughter. Despite on-going poor health she agreed to illustrate this book and I could not be more pleased. She has brought a wonderful enchantment to it.

Writing is said to be a lonely occupation, but not this time: I have had so much encouragement and support. Sincere thanks to everyone who has helped me.

INTRODUCTION

When my great friend Bob Pegg suggested that I write this book, my first reaction was to ask myself if I knew enough stories that I had not already published. When I sat down with a notebook and pen I was pleasantly surprised at the list I compiled.

There were also many stories that I knew in part. I had heard the stories told but did not know them well enough to attempt to tell them to an audience.

I was extraordinarily lucky in my young life, to meet and hear so many wonderful storytellers. During my youth we lived in three different houses and each one seemed to be a magnet for interesting visitors.

Shetland, at the latitude 60 degrees north, has long dark winter nights, which are ideal to visit and welcome visitors alike. In my childhood and youth we had no electricity and therefore no television, no phone – computers were unheard of. We did have a radio but it worked off a combination of wet and dry batteries. The dry batteries were expensive and the wet battery had to be recharged on a regular basis, so it was not surprising that the radio was used sparingly.

What we did have was books and visitors providing fantastic conversation that often expanded into storytelling. Good stories did not have to be epic folk tales, it might be no more than someone telling of a trip to the shop.

With no streetlights and pitch-dark evenings, those going out on a visit would take with them a burning peat from the fire. It would be carried in tongs or speared on a stiff wire. Outside in the fresh air and wind it would burn bright and show them the way.

If it was still burning when they reached their destination they would put the peat in the host’s fire. When going home again the reverse would be the case. In the wintertime when a household had invited visitors it was referred to as having folk ‘in aboot da nite’.

Families and friends were invited to spend an evening and later the visit would be returned. Many a time there were visitors who just called in on the spur of the moment. To visit each other was one of the ways of shortening the long winter nights.

My father, Tom Tulloch, was to be found in his workshop almost every evening. He was a wood worker and a metal worker and he often made doors, windows, wheelborrows, threshing machines, harrows, rollers and much more for friends and neighbours.

Shetland is a treeless place but in those days wood was plentiful; it came from the sea from ships sunk or damaged during the Second World War. Money seldom changed hands but anyone that my father worked for would do something for him in return.

He also had a circular saw that was driven by an old engine that started life in a car. Wood would be sawn into boards or however it was wanted but much of it was rough wood and was made into fencing posts.

Every night he had visitors in his workshop, some were there to help while others came for the crack and many stories were told, some of them were of the ‘after 9 p.m. variety’, and I wish I had paid more attention.

At this time, the Henderson brothers, John and Bertie, were regular visitors to our house. They lived in the most isolated part of the island, a place called West-A-Firth; it had no road to it and anyone going to it, or coming from it, on a winter’s night had to tackle a formidable journey through moorland and mire. No one locked their doors in those days and it was no uncommon thing to get up in the morning to find John sleeping in the resting chair beside the fire. If he had been somewhere and did not fancy the long walk home he never hesitated to come to our house, the Haa of Midbrake, to await daylight.

If the weather was really bad he might stay for several days and he was always a welcome visitor. I have travelled a good deal and I have heard scores of storytellers but none that could hold a candle to John and Bertie. When they described someone they had the knack, like a cartoonist, of making the exaggeration that brought them to life. John was also a master mimic who could reproduce the voice and mannerisms of anyone that he heard speaking or saw moving.

They never were aware of it but every time that they spoke they gave a masterclass in storytelling. Some of the things they said might, nowadays, be considered politically incorrect but it was said entirely free from either spite or malice. It is they and many others who have inspired this book.

Lawrence Tulloch, 2014

1

THE FETLAR FINNMAN

Fetlar is the fourth largest island in Shetland. It is very fertile and is sometimes known as the Garden of Shetland. Nonetheless, Fetlar folk depended on the sea for part of their living, as did other Shetland communities.

Fetlar has no natural harbour so the boats used for fishing had to be small enough, and light enough, that they could be hauled up the beach after every fishing trip. While many men worked together and went to the fishing as a crew, one young man tended to fish alone.

Erty prided himself on being the best fisherman in Fetlar and he went to sea in some very rough and stormy seas. The older men advised him to be more careful but he was entirely confident and he paid no heed to what they said.

On one really bad day, so bad that even Erty was compelled to stay on the shore, he met a Finnman on the road. Finnmen were a race of creatures that lived in the sea. They could take any form that they wished and sometimes they lived on floating islands that were invisible to the human eye. On the shore they were usually seen as tall dark, handsome men, always well dressed and rich.

The Finnman greeted Erty and said, ‘You think that you are a great fisherman but I will wager that there will be no fresh fish on your table this side of Jül.’

This was like showing a red rag to a bull. Erty bristled and was more than ready to meet the challenge. In the days that followed, the weather never relented and no fishing was possible. Erty was not too worried because Jül was some way off.

The wind blew and blew from the southeast, the worst possible direction, and even when it shifted it was never for long enough to allow the heavy seas to settle down. Erty was on the alert day and night looking for any weather window.

He had almost given up hope when, on Tammasmas Day, five days before Jül, the wind suddenly eased and went into the west. The next morning he was up long before dawn and with the first greek of day he decided that it was now or never. He knew enough about the weather to be fully aware that the lull would be no more than just that, a lull.

He put his tackle in the boat but he had no bait. It was a high tide and there was not so much as a limpet to be had from the rocks. To go without bait was a waste of time, and then he had a desperate idea.

His wife had bought linen to make clothes from and he knew that there were a number of off-cuts. He went home and got some of those and carefully wrapped strips of linen around the hooks.

He took his razor-sharp knife and made a deep cut in one of his fingers. It bled profusely and he soaked the linen on the hooks with blood. This done he lost no time in launching the boat and rowing away from the shore. He also took with him the pig, the earthenware jar in which they gathered fish livers. (Liver oil was used for the lamps and for lubricating wool that was going to be spun into yarn.) Erty knew that the liver oil could calm the sea, and given that his adventure was dangerous he felt that the oil might prove useful.

Conditions were far from ideal and but for the wager with the Finnman he would never have ventured out that day. He went directly to the nearest place where he was likely to catch a fish. He did not care what sort of a fish he caught; anything would do, so long as he could prove the Finnman wrong.

His line had been in the water for no more than a minute when he felt the strong tug of a fish on it. To his delight it was a cod, not the biggest cod he had ever caught but it would be a meal to him and his wife, and the Finnman was beaten.

As soon as he had the fish safely in the boat he made all speed for the shore but the weather was getting worse by the minute. Facing the stern of the boat he could see three enormous seas building, waves that were out of character even with this rough day.

The first wave ran under the boat and did no real damage but the second one nearly swamped the boat, and Erty knew that he had no chance of surviving the third. He remembered the liver oil and he poured some of it on the water; it had some effect but the big wave seemed to be unstoppable.

Erty stood up in the boat and with all his strength he hurled the pig, oil and all, into the face of the wave. The wave faltered, it seemed to stop and then it died down to be no bigger than any of the other waves.

By this time, Erty was close to the beach and his neighbours had heard that he had gone to the sea and they were there to look for him to try to help. As soon as the boat touched the beach, willing hands grabbed it and carried it up the beach and beyond the reach of the angry sea.

Erty had to endure several lectures from the older men but he took the cod home and it made a delicious meal for him and his wife. It was a few days after that when he met the Finnman again but this time Erty scarcely recognised him; he had a black eye, his nose was broken and some of his teeth were missing. Undaunted, Erty reminded him of the wager. The Finnman snarled at him and said through the teeth that he had left, ‘You are getting nothing from me. You spewed out that filthy oil and you struck me in the face with that stinking jar.’

Erty never saw the Finnman again.

2

THE NETTED MERMAID

Fishing with long lines was labour intensive and very hard work and not least because bait was required for every one of the four hundred or so hooks on each line. Herring and mackerel were used but time had to be spent in catching them.

The skipper of one boat decided to experiment with nets. He reasoned that they could set a few nets and fish while the nets were left to collect the desired fish. On one occasion when they came to hail the net they could feel something heavy in it.

They pulled the net in alongside the boat and they were astonished to find that they had caught a mermaid. She was terrified and she was crying in an uncontrollable manner. Her long golden hair was woven into the net as well as her fish tail.

When she looked into the boat her eyes met the eyes of one of the youngest members of the crew.

‘Help me Magnie, please help me,’ she pleaded.

Young Magnie’s father, Geordie, was the skipper and he gave his son a fierce look.

‘Do you know this creature, boy?’ he demanded to know.

Magnie just nodded. The crew pulled the mermaid into the boat and she was freed from the net. Geordie looked angry.

‘Will someone tell me what is going on?’

Magnie had difficulty finding speech and so the mermaid spoke:

‘One evening when I was sitting on a rock Magnie came close to me. Maybe I was sleeping but I never heard him or knew that he was there until he put his arms around me. He is very handsome and like every mermaid my dearest wish is to be married to human man.

‘After that we met many times and I learned to speak the human tongue. I have fallen in love with Magnie, it is a love that will never die. I know that Magnie feels the same way about me but my father will not allow us to get married.

‘Only he has the power to take away this fish’s tail and give me the legs of an earthly woman. He wants me to marry a human but he wants it to be to a rich man not a poor fisherman.

‘We had a serious quarrel this morning and I had to flee for my life. My father is an evil man and he would rather kill me than allow me to marry Magnie and he will certainly kill Magnie if he ever gets the chance. It was because I was in a panic that I swam into your net.’

Some of the men wanted to put the mermaid back into the sea and old Geordie was somewhat hostile too. Magnie spoke for the first time.

‘Father, if you put Mara back into the sea you will be sending her to her death and I will not have that; I will go with her and I will die too.’

Geordie knew that his son was determined and meant what he said so, reluctantly, he consented to taking Mara ashore with them. Magnie’s mother had to be told and though she did not like the situation, there was not much that she could do.

One of the first things that Mara noticed in the fishermen’s house was the cross that hung on the wall. It was made of iron, roughly made by Magnie when he was apprentice to the local blacksmith, and the two pieces of metal had been walled. They had been heated and hammered together to form a join. The rest of the cross had also been hammered so that it had dozens of facets. Years of polishing gave it a deep, burnished shine and for Magnie’s mother it was her most precious possession. As one who had been brought up to hate Christianity, Mara felt uncomfortable with it but she said nothing.

When Mara and Magnie were alone they discussed the situation and Magnie was in no doubt that the merman, Mara’s father, had to be confronted. Mara kept telling him that he had no idea how powerful and how evil her father really was.

She said that his power came from the knife that he always carried. She knew that without the knife he was no threat to anyone but, hard as she had tried, she had never been able to steal the knife from him. He slept with it under his pillow and during the day he wore it in his belt.

It was with the knife that he intended to kill one or both of them. Mara said that they would never be safe from him because he would patrol the shore tirelessly until he found them.

‘Right,’ said Magnie, ‘I will go to the shore now and have it out with him.’

He ignored her protests and set out for the beach, unarmed except for one secret weapon. He did not have long to wait before the merman appeared. With a face that was full of hatred he said through clenched teeth, ‘You have destroyed my daughter’s life, earthman, and for that you will pay with your life.’

He drew the magic knife and moved forward menacingly and with murder in his heart. The knife had a long, curved and wicked-looking blade. But Magnie was a brave young man, and he stood his ground. He took the cross belonging to his mother from under his gansy and held it aloft.

The cross caught the sunlight and when the first ray shone in the merman’s face he halted in his tracks. Magnie kept the cross moving and the many facets reflected the light, leaving the merman blinded and shaken. He staggered back and fell, but Magnie was unrelenting. He kept the light shining into the merman’s face and the merman began to shrink in size, his knife falling from his powerless hand.

Magnie picked the knife up and threatened the merman, ‘You were determined to kill me and you deserve to die. But I am not as evil or wicked as you are so I will not take your life. Go back to the sea before I change my mind and if I ever see you again it will be worse for you.’

The merman scuttled down the beach and disappeared beneath the waves and a new sound came to Magnie’s ears. It was Mara laughing and running down the path and into Magnie’s arms. She no longer had the fish tail, instead she had lovely slender legs; she was stunningly beautiful and Magnie was even more in love with her.

Soon they were married and went to live in their own house. Magnie left the sea to take over from his mentor as the village blacksmith, which gave him more time to spend with Mara and their three children, two boys and a girl.

As for the omnipotent merman’s knife – Magnie took it home. Mara was given her own cross as a wedding present; it was fashioned by Magnie in the forge from the evil knife that the merman once owned. Mara polished it every day and it hung in their cottage in a place where, on bright mornings, it reflected the early sun and filled the room with gladness.

3

THE LAUGHING MERMAN

A lone fisherman was rather sad because he was having no luck: he had been fishing all morning and he had shifted to a number of fishing grounds but without any luck.

He was sure his luck had changed when he felt a big weight on his line and very powerful tugging. He hauled with all his might and was amazed and somewhat dismayed when he discovered that he had hooked a merman.

The merman was small and ugly, and when he was hauled into the boat he was very angry. He demanded to be released and allowed to go back into the sea. The fisherman told him that he would be taken ashore.

‘You don’t look as if you will be for any use but I have caught nothing else so I will keep you for the time being and I will not release you until it suits me to do so.’ And he put the merman into a basket and secured the top so that he could not escape. By this time it was late afternoon and the fisherman decided that he had been at sea long enough, so he took in his lines and made for the shore.

The fisherman’s wife was there to meet him; she put her arms around him and told him how much she loved him, and at the same time the dog came to greet him but he kicked the dog and told him to go home. The merman laughed loudly.

As they walked up the path to the cottage the fisherman tripped over an embedded stone and he nearly fell on his face. The merman laughed loudly again. Later, some peddlers came to the house and among the things that they had for sale were boots and shoes.

The fisherman refused to buy any because he said that the soles were too thin and that they would not last long. The peddler showed him that the soles were double thick but again the fisherman insisted that they were too thin. The merman laughed loudly. Inside the house the fisherman demanded to know why the merman laughed, but he would say nothing.

The merman was kept a prisoner for three days and nights, with the fisherman trying to force him to explain what he was laughing at. The merman said that he would let the fisherman know, but only if he was taken back to the place where he was caught, to be released. At last they came to a compromise. The merman agreed to tell the fisherman if he was allowed to sit on the blade of an oar that was outstretched from the boat above the sea.

The merman was wise in many matters and the fisherman asked him what was the best tackle to use to ensure a good catch of fish. The merman said, ‘Bitten iron and trodden shall they have for hooks and make them where the stream and sea can be heard, and harden them in horses’ tire. Have a grey bull’s line and raw horse skin cord. For bait they shall have bird’s crop and flounder bait and man’s flesh in the middle bight and fey are you unless you fish. Forward shall the fisher’s hook be.’

The fisherman then wanted to know why the merman laughed when his wife and dog met him at the beach.

‘I laughed because you are so stupid. The dog loves you and he is your best friend but you kicked him. Your wife loves another man and wants you dead but you kissed and caressed her.

‘The stone that you cursed lies on top of a pot of gold that would make you rich but you are so stupid that you do not know this. I laughed when you would not buy the shoes because you are so stupid that you do not know they would have lasted all the rest of your life. You have only three more days to live.’

The merman dived off the oar and disappeared into the sea but everything that he said turned out to be true and a poem was written to remember this event:

Well I mind that morning

merman laughed so low;

wife to wait her husband

water’s edge did go;

kissed him there so kindly,

cold her heart as snow;

beat his dog so blindly,

barked his joy to show.

4

THE MERMAID WHO LOVED A FISHERMAN

Once upon a time there was a mermaid who fell in love with a fisherman. The fisherman was poor and the mermaid’s father would not allow her to marry the fisherman, but it was only her father who had the power to free her from the fish’s tail that was her lower body.

He tried to persuade her to look for a rich man, one who would keep her with plenty for the rest of her life. She said no, she wanted no one save the young fisherman. They sat together near the sea whenever they had the opportunity and dreamed of being married and having children.

Her father came to realise that no matter what he said his daughter would never leave the fisherman. One night when the lovers met, the mermaid had the startling news that her father had decided that the only way that he could break the romance was to kill the fisherman. The mermaid produced a knife and handed it to the fisherman.

‘This is the knife that he would kill you with,’ she said. ‘Keep it safe because it is no ordinary knife. But just because I have stolen it from him does not mean that you are safe. He has great powers and he will brew up a great storm and use that to sink your boat. When this looks like happening you must throw the knife into the sea and that will calm the billows.’

The fisherman was far from convinced but he accepted the knife, and to please her he promised to do as she said. The very next day the mermaid watched from her favourite place on the shore as her lover sailed his boat out to the fishing grounds.

He had only been fishing for a short time when the sky began to darken and the wind began to blow hard. The gentle swell turned into big, breaking waves and the boat was tossed around like a piece of cork.

Waves began to break over the boat and the mermaid knew that the boat had to be filling with water and was in grave danger of sinking. She also knew that the storm was the evil work of her father, and willed and implored the fisherman to throw the knife into the sea.

When he did not she thought that maybe he had forgotten about it so she slipped into the water and swam off to the boat as fast as she could. She was going to shout above all the noise and urge him to throw the knife.

But the fisherman suddenly remembered the knife and what the mermaid had told him, so he threw it into the raging sea. By this time the mermaid was near the boat and the knife plunged deep into her beautiful white breast, killing her instantly.

And so it was that the fisherman lost the love of his life, the merman had lost his only daughter and neither of them was ever happy again.

5

THE BLACKSMITH AND THE NJUGGEL

A njuggel is a creature that no community wants to have. Njuggels usually live in freshwater lochs, they can take on any form they want but, more often than not, they look like a horse.

Discerning folk can nearly always know a njuggel if they meet with one. A njuggel’s coat is never dry and the hair grows upwards, the opposite way from an ordinary horse. A njuggel will sometimes, on a cold, dark and stormy night, stand by the roadside and invite a weary traveller to ride on its back. But anyone foolish enough to take up the offer will always regret it. The njuggel is unlikely to take them anywhere that they want to go and, if they ever reach home, they will find that their clothes have a horrible smell, are soaking wet and can never be dried.

However, it is children that are most in danger from the njuggel. A njuggel’s tail is very long tail and it can shape it into a wheel of sorts, which can spin around. Children find this most attractive and the njuggel will invite a child to sit on it for a ride.

Any child who sits on a njuggel’s tail is doomed; the njuggel will take the child into the loch never to be seen again. On one island the njuggel had preyed on so many children that very few were left.

One who had so far managed to elude the njuggel was the blacksmith’s daughter. She was an early teenager, and she was big and strong like her father, and she had eluded the njuggel despite all his efforts to capture her.

Eventually the patience of the njuggel was exhausted so he took a direct approach. He arrived at the blacksmith’s forge full of menace and in a wicked temper. He demanded that the blacksmith hand over his daughter saying that if he refused he would be killed. The blacksmith stood his ground, looked the njuggel in the eye and said, ‘You will never have my daughter. She is all I have, especially since her mother died. She is the apple of my eye and I defend her with my life.’

The njuggel’s face went black with rage and he stamped his hoofs on the ground.

‘I will give you one last chance,’ he said. ‘I will come back in twenty-four hours and if you hand over the girl well and good but if you still refuse I will kill you and take her anyway.’

Twenty-four hours gave the blacksmith time to prepare and he told his daughter what he planned to do and what he wanted her to do. That done, he set about making some special thick, extra heavy horse shoes for a very special horse.