Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

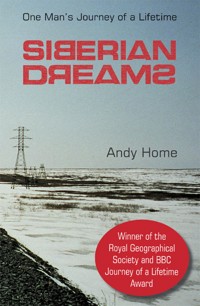

Every year thousands compete to win the RGS/BBC Journey of a Lifetime award and fulfill their travel dreams. However, Andy Home's dream would be most people's nightmare. Andy went to Siberia, to the Russian industrial mining city of Norilsk where temperatures drop to minus 50, half the year is spent in perpetual darkness, and the pollution has destroyed all natural life. Once a prison camp, then a secret Soviet military city, Norilsk teetered on the edge of financial and social meltdown in the early 1990s. Now, it is owned by one of Russia's new breed of all-powerful oligarchs and is the biggest single source of common industrial metals. Andy's quest was to meet the former Soviet shock workers and ask them what life is like in 21st-century Russia. This is a fast paced, humorous, and insightful account of an extraordinary journey of a lifetime.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Copyright © Andy Home 2006

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher.

Andy Home has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

Siberian Dreams

1st Edition

Date 2007

Published by Eye Books Ltd

Eye Books

29 Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

website: www.eye-books.com

ISBN 10: 1 903070 51 1

ISBN 13: 978 1 903070 51 2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Set in Frutiger, ITC Garamond and Helvetica Inserat

Cover design by Peter Scott

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Creative Print and Design

Norilsk-Dudinka Road, Siberia

Dedication

To John Pilkington, founder of the Journey of a Lifetime Award, and the Royal Geographical Society, for believing that the world must always be re-discovered.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1 GETTING THERE: The Man in the Ministry

2 ARRIVAL: ‘Back in the USSR’

3 INSIDE NORILSK: Through the Looking Glass

4 FIRE AND ICE: ‘Welcome to Hell’

5 SECRETS: Ghosts in The Machine

6 INNER SANCTUMS: ‘BBC or British Intelligence?’

7 ESCAPE TO SIBERIA: ‘You’re lucky you’ve seen this’

8 THE LEVIATHAN AWAKES: Coming in from the Cold

POSTSCRIPT

APPENDICES

INTRODUCTION

I first heard about the Journey of a Lifetime award from a friend.

Fifteen years of comfortable middle-class life in a leafy suburb of London had recently dissolved into bankruptcy and redundancy, both of my employer and my personal relationship. Forcing myself to focus on the dwindling positives in my life - free time, no commitments, and a hard-fought-for but ultimately generous pay-off - I’d decided to take a year out of the rat race and fulfil some long-cherished travel schemes.

That year had passed wonderfully but all too quickly and I’d returned from my journeying to try and figure out what to do with the second part of my life. I was contemplating my long-out-of-date CV when the phone rang.

My friend Pete had just heard about the Journey of a Lifetime award on Radio 4. A joint annual initiative between the BBC and the Royal Geographical Society, the deal is deceptively simple. You write in with the details of the journey you’d most like to make, and if they like your idea more than anyone else’s, you get £4,000 to undertake it and make a radio programme for the BBC about your experiences.

‘You could go to that place in Russia you’re always banging on about,’ Pete said.

It’s not every day you get offered money to take your trip of a lifetime. It seemed ridiculous NOT to write in, particularly since I was struggling to think of how exactly I was going to pick up the pieces of my shattered life. My ‘journey of a lifetime’ might be bizarre enough to at least catch someone’s eye in the hundreds of application letters that would flood in to the Royal Geographical Society.

What Pete said was true. I had been banging on about the place for years. What had started as a joke among work colleagues - ‘Behave, or I’ll send you on a fact-finding mission to Norilsk!’ - had slipped unnoticed into my sub-conscious over the course of time. Not strong enough to be called accurately an obsession, it had nevertheless become a familiar part of my mental furniture, a curiosity to be trotted out occasionally during late-night ramblings with friends about weird travel destinations.

I admit I was unusual in even knowing of the existence of this mining city in Russia’s frozen Siberian expanses. I only did so thanks to my career as a financial journalist. I’d written about commodity markets and then I’d progressed to managing other people who wrote about commodity markets. Oil, gas, grain, sugar, coffee, cocoa and rubber - most of us take them for granted, and most of us are blissfully unaware of the powerful forces that make these building blocks of life some of the most volatile markets in the ever-expanding world of global trading.

My area of special expertise encompassed the markets for industrial metals such as copper, aluminium, nickel and zinc, the raw materials that invisibly facilitate much of our modern, day-to-day life.

Norilsk is a massive producer of metals. Inside the Arctic Circle, literally in the middle of nowhere, some 200,000 inhabitants live and work around its sprawling network of mines and metallurgical factories. Winter lasts eight months. Temperatures drop to levels I find impossible to get my head round. It has periods of both twenty-four-hour night and, during the brief summer, twenty-four-hour daylight. It’s the biggest single source of industrial pollution in Russia, which means it’s off the scale of any other developed country.

The more I’d written about the metals that spewed out of this Siberian giant, the more I’d wondered about the people who lived there. My career as a financial journalist had not been planned. It had resulted from a couple of fortuitous turns in an otherwise directionless path. Was that also how you ended up working in a polluting metals plant in what must be a strong candidate for the world’s grimmest city? And if a couple of life’s rolls of the dice had brought you there, why on earth would you stay?

With my growing curiosity about life in this alien city had come a different set of questions. Questions about Russia. Norilsk’s history is as alien as its climate, but it is one that has melded the place into a refracted Siberian reflection of Russia’s uniquely weird development over the second half of the twentieth century.

From a gleam in Josef Stalin’s eye in the 1930s, Norilsk was born as a prison camp in the Soviet gulag system and remained so until after his death in the 1950s. Then, like many other camps, it metamorphosed into a closed city, part of the Soviet Union’s huge military-industrial complex, near invisible to outside eyes. Only with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, and the resulting tidal wave of change that swept eastwards, did Norilsk emerge into at least partial daylight.

Its only customer, the Soviet military, had just gone out of business and it survived in the only way it could, by exporting its metals to the West, to us. It was still touch and go as to whether it would survive, though. There were times in the 1990s when the miners weren’t paid for months, the power stations were failing and the company which ran the whole place, Norilsk Nickel, was technically bankrupt. And to rub salt into the wound, most Russians had just seen their savings wiped out, which meant that no one had any money to leave Norilsk, whether they wanted to or not.

Since then, though, it had hauled its way back into profitability thanks to the intervention of the enigmatic Interros Group, the corporate embodiment of one of Russia’s new oligarchs.

The multiple personality changes of this far-flung city made me come to view Norilsk as an Arctic palimpsest of all the drunken lurches in Russia’s stagger to the new millennium.

I had never been to Russia. I consider myself both a moderately literate and well-travelled man, but Russia in any living sense was a void to me. Beyond a schoolboy knowledge of its history and a lot of dry financial facts and figures, my visualisation of the place didn’t extend much beyond a random collage of parts of the film Doctor Zhivago, a few of the James Bond series, and footage of the May Day parades in Red Square with all those missile launchers rolling past.

That last bit, of course, was also the main reason for my almost complete lack of knowledge about the country. It’s easy now to forget how long the Soviet Union was our enemy, that swathe of red sprawling across the pages of the atlas, making Western Europe look like a small, messy disintegration of land into the sea. Generations of us lived under the threat of nuclear obliteration by this menacing eastern giant. What else were those May Day parades about, if not a blunt way of saying, ‘Look how many tanks and missile launchers we have’?

When the Soviet Union finally collapsed under its own inert weight in the early 1990s, Russia was welcomed back by the rest of the world as a long-lost relative. I happened to be in Rome when President Gorbachev visited the city. Hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets to hail this liberator of the East.

But the public interest didn’t last more than a handful of years of curiosity - ‘So, how have you been all this time?’ - before it shifted elsewhere. The typically Russian shambles of a coup attempt in 1991 seemed to reassure the rest of the world that the country could safely be left to shuffle along in its own chaotic way without too much scrutiny.

Friends went on weekend city-breaks to Moscow and more so to St Petersburg. Everyone told me I should go and see the Hermitage museum. But I didn’t want to go and see the pre-Revolution palaces of the Tsars. These buildings, however impressive their façades and however delightful their interiors, would not help me find out about the Russians. Who the hell were these people who had been my enemy for half a century? And what were they up to now? Was life good? Was it better than it had been?

If I was going to get any insight at all into this country of 200 million people which Winston Churchill described as ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’, I would have to go to somewhere I could peek up Mother Russia’s skirts.

Norilsk, I reckoned, was the perfect vantage spot - half a continent distant from Moscow but with a history completely intertwined with the arrhythmic heartbeat of the Kremlin. The hardy souls of Norilsk could tell me a bit about what life was like as a Russian. Norilsk was my dream ‘journey of a lifetime’. I wanted to go to Norilsk and ask people there what their dreams were.

There was a practical problem, however, which was my almost total lack of Russian. So I asked a Russian friend and former colleague to apply with me. Grigori liked the idea a lot. He had his own reasons for wanting to go back to see what Russia was like.

The Royal Geographical Society and the BBC liked the idea a lot as well. Frankly, I’m fairly confident that among the 600 or so applicants for the 2003 award they received only one letter asking to go to a Siberian industrial mining city. I suspect they hadn’t received one before and they haven’t since.

My girlfriend told me I was ‘off my rocker’ when I explained to her what I was going to do. I didn’t begrudge her the reaction. I heard it in various forms in the time between being told we’d won the Journey of a Lifetime award and actually setting off in May 2003. ‘But you could have gone anywhere!’ wailed another friend in disappointed disbelief.

Grigori and I went on a training day at the BBC and were given a crash course in recording for radio. Within a few days I’d forgotten most of what they’d told us and was only left with the memory of how many times both of us had messed things up in our practice sessions.

The following is an account of what happened to us on the journey. I have taken some minor liberties with the time sequencing for dramatic effect and have edited the transcript both for reasons of comprehensibility and to excise moments of stupidity and/or inarticulacy. Otherwise, it is a truthful account of our experiences.

GETTING THERE The Man in the Ministry

We are sitting nervously in a small anteroom next to the office of one of the most powerful men in Russia and he is keeping us waiting. ‘We’ are myself, Grigori and Sergey and ‘he’ is Dmitry Zelenin, the man who will decide whether we get to go to Norilsk.

Grigori is my co-traveller on this trip. Born in Moscow, he has twice left his native Russia, first as an émigré Jew in the 1970s and then at the end of the 1990s after several years of growing disillusionment with the new, post-Berlin Wall Russia.

If I have the role of ‘stupid white man’ on this journey, Grigori plays the part of ‘wise native guide’. This will suit him, because somewhere in his kaleidoscopic life, with stints in two different armies, three marriages, books of poetry in Russian and English, a job as a street cleaner and, perhaps most bizarrely, a sideline in playing trumpet in a 1960s Soviet jazz band, there was also, I’m pretty sure, some acting involved. I can’t say for certain. I find it hard to remember all Grigori’s life-stages.

In many ways, he has been my guide to Russia since our paths first crossed in the early 1990s. I was then a reporter for a now-deceased financial news-wire. As our Moscow Correspondent, he had been a willing and concise teacher of how in Russia nothing was ever quite what it seemed. In his country, the ‘news’, particularly political and financial news, was little more than ‘noise’, a distraction from any useful analysis, he used to explain. Day-to-day events were merely a hall-of-mirrors distortion of deeper-lying realities. But looked at from the right angle, they could also be a prism through which to see a constantly shifting game of power, politics and money.

Grigori is on this trip to test his own ambivalent feelings about his mother country. For me, it’s precisely his combustible mixture of pride, fear and loathing of Russia that makes him such an invaluable guide.

I also need someone who speaks Russian because I’m not sure how far I’ll get in this vast country with only four words - ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘vodka’ and ‘cheers’. As well as his mother tongue, Grigori is fluent in English, although sometimes his dilettantish past means he has a tendency towards the poetic, which is often amusingly juxtaposed to what he is actually saying. I regret that my almost complete lack of Russian prevents me from knowing whether he talks this way in both languages or just in English.

But Grigori, like a lot of Russians, has not been to Siberia. And that’s why Sergey is the third man on our expedition.

Sergey comes from Irkutsk in eastern Siberia. He’d been a photographer for the official Soviet Tass news agency before he moved to Moscow and started working with Grigori as a journalist. He’s been at least twice to the North Pole, and he’s been to Norilsk a couple of times as well, which should come in handy.

Grigori has told me that Sergey smashed his skull in a climbing accident and has a large metal plate in his head, sitting beneath his mini bearskin of dark hair. Sometimes it makes him ‘a bit funny’, Grigori added conspiratorially.

Grigori also frequently tells Sergey he looks like ‘a Georgian’ because of his bushy moustache. This makes them both laugh a lot. It’s a Russian thing.

The last time they met was a couple of years ago, when they cycled the length of the UK from Land’s End to John O’ Groats in eight days. Cycling is Sergey’s big thing. When we were all working together back in the 1990s, I was once taken aback to learn that Sergey was going to use his two-week holiday to go for a cycling trip in Mongolia. Now, that is a Siberian thing.

Grigori Gerenstein: Moscow

Sergey Padalko: Kitchen in Sergey’s Moscow apartment

Closed City

Sergey is our Mr Fix-It on this journey. And his first task is to help us get some permits to go to Norilsk.

The city of Norilsk is not only absurdly remote, even by Russian standards, but it and the port of Dudinka nearby are now also ‘closed to foreigners’, part of a discreet closing of the curtains that is creeping across Russia.

‘Closed’ cities are supposed to be a thing of the past. Pre-1989 they were dotted throughout the then Soviet Union, coming together in occasional clusters in particularly remote regions of the red empire. In Russia itself, they included really big cities such as Krasnoyarsk, Vladivostok and Perm. Access was denied to anyone carrying a foreign passport. In most cases access to Russians was also denied.

Norilsk had been one of these cities. Controlled by the Ministry of Defence, the metals from its labyrinth of underground mines in the Arctic Circle were channelled through a secret grid of other closed cities to be used in the Soviet Union’s voracious arms industry.

All that changed after 1989. The ‘closed’ cities were opened, an internal blossoming to match the sudden unveiling of Russia itself. Article 27 of Russia’s new constitution guaranteed complete freedom of movement to ‘everyone legally present in the Russian Federation’, regardless of citizenship.

The new openness didn’t last very long, because in 1992 the then prime minister, Yegor Gaidar, signed Decree No. 450, limiting access once again to some ‘sensitive’ areas, those close to key borders or near military facilities. The decree was updated every couple of years throughout the 1990s, each revision adding a few more names to the list of no-go zones.

The Atomic Energy Ministry and the Defence Ministry also reserved the right to close off key installations and the towns around them. The Atomic Energy Ministry has published details of ten such places. The Defence Ministry says its information is a state secret and won’t say how many it has re-closed.

The thing about Norilsk, though, is that it asked to be re-closed. The company that controls the city, Norilsk Nickel, applied to Moscow in 2001 to have itself locked away again from the outside world. It cited the recent influx of ‘foreigners’, economic migrants from former Soviet republics far away in the South - Azerbaijan in particular. Mostly unable to find long-term employment in the company’s mines and factories, they formed a sub-class of vagrants and criminals, the company and the city officials told Moscow. Heroin, a commodity previously unknown in the Arctic North, had insidiously crawled its way into the community, they said. Crime, also a rarity in the old days, had grown at alarming rates, they said.

At least 40,000 local people agreed with them. That’s how many apparentlyi signed a petition asking for the ban on ‘foreigners’. That’s just over one in five people living in Norilsk and its satellite towns.

The Russian government agreed, and within months old-style travel restrictions were put back in place and the city started disappearing from view back into the Arctic snow whence it had briefly emerged. To get there now you need a special permit. There are only two ways to get a permit: be related to someone in the city, or get an official invitation from Norilsk Nickel itself.

And although the travel ban applies to all ‘foreigners’, there’s ‘foreigners’ and then there’s ‘foreigners’. In the case of Norilsk, this is not a simple return to the days when ‘closed’ cities were sealed off to keep away prying Western eyes. ‘Foreigners’ from Europe, North America and Japan are welcome in Norilsk, particularly if they are bankers, equipment suppliers, technical consultants or, best of all, buyers of the company’s metals. The ban really only applies to ‘foreigners’, those from the periphery of Russia’s once sprawling empire.

But you still need a permit. Or that is, I need a permit. So does Grigori, and so does Sergey.

The issue of the permits has loomed ever larger in our planning of this journey, a black dot on the horizon that has grown steadily over the preceding year to assume truly monstrous proportions.

‘What about the permits?’ I asked Grigori when we first sat down and talked about the idea of travelling to Norilsk as a journey of a lifetime. He told me enquiries would be made via Sergey.

A few weeks later, he told me the company was keen to invite us ‘to make a programme for the BBC’ and getting the permits would be no problem.

The issue naturally arose in our interview with the Royal Geographical Society and the BBC on the hallowed ground of the Society’s Victorian brick headquarters on Kensington Gore in the heart of London. Grigori told them what he’d told me. I nodded in what I hoped was a reassuringly confident way.

Three months later and one month before our flight to Moscow, still no permits. Grigori told me there had been ‘a little problem’, three words which caused my stomach to start tightening.

The ‘little problem’ was a very Russian problem. Norilsk Nickel was only too happy to give us the permits, but the Duma, Russia’s parliament, had passed a new law on travel restrictions to closed cities which in turn meant new paperwork. But President Vladimir Putin hadn’t signed the law, meaning it could not officially be enacted. The company didn’t want to issue us with the old permits in case they were rendered obsolete by the new permits.

‘When’s Putin expected to sign the law?’ I asked Grigori. He shrugged. ‘Who knows? It’s already been waiting several months for him to sign.’

It was not the answer I wanted to hear.

On 18 May 2003 we left for Moscow. We did not have the special permits for travel to Norilsk. I heard the beating black wings of suppressed panic following me up the steps onto the plane. Our budget for the trip was £4,000. An eighth of that was already spent on the flights to Moscow. I didn’t relish going back to the BBC and telling them we’d need some more money because we didn’t get our permits.

Grigori was all breezy confidence, telling me everything would work out. ‘You’ll see!’ Anyway, he said, Moscow would be good acclimatisation for me before I went to Norilsk. ‘So you can see the place like a Russian!’

Maybe…

Moscow

You don’t so much drive in from Moscow airport to the city, rather it races out to meet you. The commercial sprawl seems to be dashing to break free into the birch forests that surround the Russian capital. Some of it is still half-built. Through the steel skeleton of what will be a space-age superstore, I catch glimpses of fields and small clusters of dismal-looking tower blocks.

A massive, shiny-new Ikea with a giant banner proclaiming ‘WE’RE GOING TO THE DACHA!’ is still surrounded by half-waterlogged fields. Assorted cows stand chewing the cud and contemplating this wondrous addition to their landscape.

A few miles from the airport Grigori points out the famous tank-traps set in the road, marking the point just ten miles outside Moscow where the German army ground to a halt in the Second World War. A couple of hundred yards further on a gleaming McDonald’s beams down ironically on this memorial to Soviet sacrifice.

It’s only a few minutes after this new landmark of consumer capitalism that we hit the first of a series of seemingly interminable traffic jams. As our progress slows to a near standstill, Sergey entertains us with the story that has gripped Moscow for the last few days. Grigori translates for me.

The 8 May Victory Day Celebrations had been thrown into chaos by a homesick soldier going AWOL in possession of an army oil tanker. He had taken a wrong turning on the ring-road trip to his mother’s apartment and had started heading for the centre of town and the official celebrations. In a city that has seen Chechen rebels take hostage an entire cinema, this had understandably caused something of a panic and had led to a spectacular televised car chase with the police shooting out the tanker’s tyres, only for them to automatically inflate as apparently they are designed to do.

‘Good Russian technology,’ Sergey and Grigori nod in agreement at this stage.

Anyway, the speeding reservist had only been stopped when the police had set up a roadblock improvised from bulldozers.

‘And just because he missed his mother,’ Grigori translates the punch line.

The Russians in the car, including the driver, think this is just the funniest thing they’ve heard. There’s a lot of laughing.

‘Didn’t the guy think it was strange that he was being shot at?’ I ask ‘He was probably drunk, maybe something more… anyway, he’s a soldier, he’s used to being shot at,’ Grigori manages to reply through splutters of laughter.

It’s the first example of Russian humour I’ve encountered in the raw. As I realise over my ensuing time in the country, Russian jokes always seem to be tinged with a darkness that adds a new dimension to what we Brits like to boast is our own black sense of comedy.

Moscow is huge. Or maybe it just feels that way if you’re stuck in a traffic jam most of the time. It’s obvious the last few years have been good for the advertising industry since large parts of the city are dripping with billboards and neon signs. Behind this recently acquired glitz, though, the city is still largely a vision of Soviet planning - an endless jigsaw of grey, utilitarian, concrete buildings.

After an hour and a half of inching through traffic, we reach a purely residential area which is where Sergey lives and where we’ll live until we get our permits for Norilsk. If we get our permits for Norilsk…

The vista is one of countless apartment blocks stretching down wide roads that disappear over the horizon in canyons of brick and glass.

The car finally stops in front of a couple of particularly kicked-in looking buildings. After unloading ourselves and our luggage, we stand on the walk-way leading up to the front entrance and decide to have a go at recording our first impressions of our new temporary home.

Grigori and I have an abiding mistrust of the equipment we’ve been given, having managed to accidentally erase whole tracks during our practice day with the BBC. At this stage our comments to the mike are interspersed with panicky exclamations such as, ‘Is it still on?’ and ‘Why’s it blinking like that?’ Nor have we got used to each other’s speaking rhythms. The recordings are full of long breaks when one of us has stopped talking and the other one is respectfully waiting for the flow of words to continue before realising it’s his turn. Over the first few days of our trip we evolve our own nonverbal system of meaningful glances and nods to indicate the recording baton is about to be passed back.

Transcript.

Moscow.

Arrival at Sergey’s flat.

Grigori: We’ve arrived at an apartment block about forty minutes from central Moscow. We’re very near the edge of Moscow. It’s where ordinary Muscovites live. I can assure you no tourists or Western businessmen come here.

Andy: I guess I’d describe the building as a medium high-rise, about twelve stories high. It looks as if it’s seen a little bit better days.

Grigori: It’s Brezhnev style, 1980s, so they really look pretty awful.

Andy: They look as if someone’s just kicked the crap out of them.

Grigori: A similar area in London would be working class but here it isn’t the case. There are hardly any working-class people left in the city, it’s intelligentsia and middle class in these areas.

Andy: There are people I would regard as looking very poor, they’re in tracksuit bottoms and such. Frankly, they look like muggers. But they’re standing next to people looking very posh. Everyone’s mixed together. I couldn’t say whether they’re working class or middle class. And all sorts of nationalities, that’s something I’ve really noticed here.

Grigori: Just people hanging out. It’s all very sociable.

Andy: On the other side of that road over there? Are those ponds and lakes?

Grigori: There is a park and the remains of a village built by Catherine the Great for one of her lovers. The story is, she and her lover fell out and she ordered it to be destroyed but she died before she could do so. It’s eighteenth century. Most buildings built by Khrushchev and Stalin have already collapsed but those from Catherine the Great’s time are still standing.

Andy to Sergey: Is this a safe place to live?

Sergey via Grigori: It’s perfectly safe. There is no crime here. Okay, if you get involved with some market-place traders, like shaking them down or something, you may get killed or whatever. But if you’re just a normal citizen living here, you’re much safer than in most European towns.

Andy to Sergey: How much does it cost to live here?

Sergey via Grigori: $350 per month. (Sergey shrugs his shoulders philosophically). It’s okay. It’s medium.

Andy: If you were standing in a place like this in the UK, you’d see graffiti, you’d have vandalism, you’d be running away from the kids, you’d…

Grigori: … you’d be standing without your trousers.

Sergey’s ground-floor flat is cosy enough inside. One bedroom, one lounge (our bedroom), a small bathroom and a kitchen. In the hallway are three bicycles.

Grigori laughs at me for taking off my shoes and producing a pair of slippers from my travel bag. Then Sergey tells him to take his shoes off whenever he comes into the flat. I grin. A small one for the Stupid White Man!

We celebrate our arrival in Russian style. Sergey produces a roast chicken, a range of smoked fish, cold meats, salads and fresh black bread and lays it on the small table. He takes a bottle of vodka out of the freezer, provoking a long and detailed conversation in Russian between him and Grigori.

Grigori finally turns to me and says the vodka is a new brand which has just been launched and is apparently very good. It is called ‘Stalin’. It is made to Uncle Joe’s favourite recipe. What would the great leader have made of his name being used as a marketing brand, I wonder. For that matter, what do I make of drinking a vodka named after a psychotic mass murderer?

The vodka is very good, though. Crystal clear and clean tasting. It goes well with the food. The shots, which apparently always require a toast, build to a warming sensation of well-being that gradually spreads up from the pit of my stomach to my head. The three of us finish two 500ml bottles before Grigori and I get into our makeshift sleeping accommodation in Sergey’s front room.

The kitchen becomes the communal meeting room over the next couple of days as Sergey works away at his contacts to get us our permits. He’s also trying to fix up an interview with one of the former Soviet-era managers of Norilsk who is now based in Moscow. This all means a certain amount of pottering time for Grigori and me as we adjust to life in our new surroundings… a Brezhnev-era tower block on the edges of Moscow.

I’m immensely frustrated by this hanging around and only just managing to keep at bay a growing anguish that we’re not going to get the permits. We’ve booked return tickets to London in two weeks’ time. Every hour spent here is an hour not spent where we’re supposed to be… in Norilsk itself.

I drink black tea with Grigori at the kitchen table. I try and concentrate on reading the books about Siberia I’ve brought with me. I begin the audio journal I’ve agreed to keep during our ‘journey of a lifetime’.

But as idle hour follows idle hour, I also start to realise that Grigori was right in what he said about acclimatisation. I don’t notice it to begin with, but this highly unusual first experience of Russia is starting to prise away layers of preconception and misperception.

In addition to the shoes rule, Sergey insists that any cigarettes be smoked outside. For me this involves regular trips to one of the communal porches that project from the front wall by every entrance to the block. This becomes my vantage point for starting to learn how they live here in Moscow.

The porches themselves look a bit like rural bus shelters, a wooden bench running down one of the concrete sides, the other side open to the pathway. They prove to be hives of sociability for residents of the tower block. The complexion of the occupants changes over the course of the day. From Babushka grandmothers in the morning to guys watching guys mending their cars in the afternoon to kids in the early evening to their parents in the late evening.

The whole length of the block of flats is punctuated by these regularly spaced social gathering places. The next block is the same. All the blocks seem to have their own shifting pattern of porch socialites.

Opposite the flat, mothers supervise their children in a communal playground. Shoppers trudge down the street with bulging carrier bags. People walk their dogs. There are many breeds I’ve never seen before.

Sergey’s street, like many running through this Soviet skyline of rectangles, is lined with lilac trees. It’s spring in Moscow, the temperature’s getting into the high twenties and the still faint smell of lilac drifts on the occasional breeze.

Far from being the bleak, wind-swept housing estate I’d expected on first sight, the place teems with life at just about every hour of the day. There is no graffiti. There are no broken windows. There are no menacing groups of hooded teenagers like those who instil a sense of watchful foreboding in any visitor to much of the UK’s communal living space.

Evenings bring what looks like an ice-cream van to the end of the road. It is in fact selling alcohol and is crammed with bottles of beer, wine, vodka and alcopops. It is soon surrounded by a throng of people of all ages and all types - couples, families, groups of teenage girls, muscled men of conscription age.

It’s as if someone has managed to remove the pub building, while leaving the customers doing exactly what they were doing. Everyone’s just standing around chatting, drinking and smoking cigarettes. Beer seems to be the most popular drink, even with the women. Grigori tells me that it was strictly forbidden to drink alcohol in public under Soviet laws, so there’s an element of lingering defiance about these open-air gatherings.

In fact, they’re a hallmark of Moscow, as I find out the next day when Grigori takes me on a whistle-stop tour of the city centre. As well as the numerous bars and restaurants in the centre of town, Moscow is sprinkled with groups of outdoor drinkers standing around alcohol kiosks or one of the vans. I never witness any trouble among any of these groups, even late at night, which is only surprising if you come from England.

From Sergey’s apartment on the very outskirts to the centre of Moscow is a forty-minute journey on the underground system. To someone who lives in London the Moscow tube system is a wondrous revelation. A Stalinist showpiece, the stations are lined with marble columns and the trains run with almost unbelievable regularity. Every platform has a small electronic display at one end, counting down the minutes and seconds to the next arrival. I become fixated by these ticking numbers as we criss-cross the central underground system. I never see any of them start from over two minutes.

The centre of the city is bustling with activity. The pavements are heaving with well-dressed men and women and the streets are filled with cars locked in the ebb and flow of what appears to be semi-permanent traffic gridlock.

Grigori shows me the tourist sights, which in Moscow largely means the Bolshoi Theatre, Red Square and the Lubyanka.

The Bolshoi Theatre is a rare burst of neoclassical architecture in the sprawl of Soviet greyness. Its columned portico and geometrically perfect, tree-lined square and fountains are a distant echo of cities closer to home at the western end of our shared continent. But here in this city, the Mediterranean grandiosity of the design simply makes the Theatre look out of place and out of time, as if it’s been thoughtlessly transplanted from somewhere completely different.

Red Square looks drab next to the pulsating streets around it. It doesn’t help that St Basil’s Cathedral is partially draped with green netting for renovation work. Nor that one end of the Square is dominated by a huge stage being put up for a concert by Paul McCartney. I wait for a sense of history to surge up in me. It doesn’t.

Grigori tells me the folkloric history of St Basil’s Cathedral. Apparently it was built on the instructions of Ivan the Terrible who was so pleased with it that he had the architect blinded so he couldn’t ever repeat his success.

I’m faintly shocked by the story. Upon reflection, I realise that it is not so much the cruel act itself that disconcerts me as the fact that this is still the conventional tourist commentary on the building. London’s history is equally laden with its own historical horrors but the city has taken care to overlay them with a gaudy veneer of union jack T-shirts and plastic policemen’s helmets in a very twentieth-century display of prurience.

Moscow has no such embarrassment about its blood-soaked past, which is why the Lubyanka is also one of the top tourist spots in the Russian capital.

The Lubyanka, the dreaded headquarters and prison of the KGB, the former secret police, is now everyone’s favourite photo opportunity. The building is imposing enough with its carefully planned symmetry of windows and lines, but the jaunty yellow paintwork jars with the knowledge of what terrors it has witnessed over the years.

Grigori insists on taking a photograph of me in front of it. Passers-by laugh and smile appreciatively. ‘Everyone does this… that’s why they’re laughing,’ says Grigori.

No one seems to mind that the KGB’s successor, the Federal Security Service Directorate (FSB) still uses it as its headquarters.

Moscow is evidently going through something of a boom time. It has the vibrancy that comes with money being made and lots of it.

I guess I expected a dour post-Soviet city of downtrodden workers and streets empty of life apart from the odd wheezing Soviet-designed car. What I get is designer shops, conspicuous wealth and sports utility vehicles.

My discomfort in just how wrong I have been about this place is partly lifted by the fact that Grigori seems even more surprised at what Moscow has become.

The last time he lived here was in the early 1990s in the days following the disintegration of the former system. Russia’s new leadership proved completely unprepared for the cataclysm that had befallen it.

Gorbachev, after all, had only meant to prise open the door a little to let in some fresh air. The resulting whirlwind had flung him and the rest of the party apparatus to the other side of the room.

The subsequent economic collapse and ‘shock therapy’ii managed to wipe out just about everyone’s savings, stop pensioners being paid and bring large parts of the country’s industry to a grinding halt due to a massive collective liquidity freeze.

In return for Soviet-era security, Moscow’s citizens got ‘Wild East Capitalism’. Gun-battles raged through the city as the financial carve-up of the former Soviet Union was fought out. Conflict on the street between black-market gangs over drugs territory was mirrored by pent-house assassinations among the big money men trying to get their hands on the still-huge Soviet raw materials industries.

Most businesses, including those set up by Western companies, were expected to pay protection money. One of the first commodity trading companies to set up business in Moscow at the time was subjected to a terrifying attack by hooded armed men, who viciously beat up several staff members. It was said they hadn’t paid. Or maybe they’d just crossed someone they shouldn’t have crossed.

Even a taxi ride from the airport to the city centre amounted to a flirt with real danger. The bodies of several unsuspecting Western businessmen had been found at quiet spots just outside the city’s perimeter. Everyone got a friend or hired car to meet them at the terminal building, which is exactly what we had done of course.

It wasn’t too safe for financial journalists back then either. Grigori had the good sense to locate our Moscow news bureau in the grounds of a Central Asian embassy building - security included.

Grigori takes me for a beer at the five-star Meridian hotel and we sit in a cool marble-floored bar, listening to an assortment of ring tones from the mobiles clutched by the businessmen at the tables around us.

As we leave the hotel, Grigori stops in the lobby - ‘the most dangerous place to be in Moscow back then,’ he tells me with wide eyes and then a characteristic grin. This was a favourite spot for Russia’s jostling would-be tycoons to be assassinated.

As we wind our way through a series of drinking holes that evening, Grigori tells me repeatedly he can’t believe the changes since he was last here. ‘Everyone looks so content. Everyone looks so well off. Everything feels so safe.’

We put the last part to the test when we come out of the underground station back in Sergey’s district later that night.

As we emerge from the stairs into the fresh night air, we come to a stop and look around us. We are faced with an endless mosaic of tower blocks of varied size and age. As far as the eye can see they stretch in every direction. Both of us scour the horizon for any landmarks.

We realise we haven’t a clue how to navigate the intricate web of paths and small roads that criss-cross the blocks to find our way back to Sergey’s.

The streets out here are much quieter now. There are no pedestrians and just the occasional car. The only people in sight are three particularly dishevelled-looking drunks sitting at the entrance to the tube station. Grigori is reluctant to engage them in conversation. He tells me he thinks they’re from the Caucasus. I’m already learning that this is Russian shorthand for being a dangerous, drug-peddling terrorist.

But lacking any other obvious choice, Grigori reluctantly walks over to them and asks for directions. After several confirmations of the details, one of them staggers to his feet and accompanies us to the start of three footpaths leading into the maze. Although swaying gently in the night breeze, he gives us a coherent explanation of the complex route we have to follow, pausing occasionally to make sure Grigori has taken it all in. Waving us off, he wishes us good luck and returns to his two friends for a resumption of the animated conversation we had interrupted. Within ten minutes we’ve found our way home.

Jeez, even the drunks are helpful in this reborn city.

The next morning Sergey tells Grigori and me it is our turn to do the shopping while he finalises the deal that will see us get our permits issued. The supermarket is a five-minute walk away and in daylight we’re confident of finding it. It proves to be an illumination to match anything I have yet experienced.

What was I expecting? Sheepishly, I have to admit my image of a Russian supermarket had got stuck in a bygone age sometime before 1989, when the vegetable section sold week-old cabbages, the meat section sold summer sandals and the fish section was permanently empty.

This, however, is of a size and splendour to match anything back home. The fresh fish section is selling fresh fish, the meat section is selling fresh meat and the delicatessen section is selling an intimidating selection of cold meats and cheeses.

The only noticeable difference from my local Waitrose is the inversion of space in the alcohol section. Where the wine should be - under small blackboard signs denoting country of origin - is the vodka section, stretching down the side of a whole aisle. The wines are limited to a few shelves tucked away at one end, just as the spirits section would be back home. We spend an inordinate amount of time trying to choose a vodka. In the end we decide on the Stalin brand. ‘I tell you something about Stalin… he really knew his vodka,’ Grigori tells me for the tenth time since we opened the first bottle.

We arrive back laden with food and elated by the unexpected cornucopia of a suburban Muscovite superstore.

Sergey adds to our good humour. The deal is on. Dmitry Zelenin will get us our permits. We get to interview Dmitry Zelenin in return.

The Man in the Ministry

Zelenin is very rich. Not a billionaire but a multi-millionaire. He was president of finance at Norilsk Nickel between 1996 and 2001. He was part of a team of young technocrats brought in to manage the place when it was bought by the Interros Group. He’s also a senior manager in Interrosiii, one of the mammoth financial and commercial groups that now control large swathes of the country’s economy. Its interests range from industrial metals to insurance companies, from power plants to newspapers, from banking to ski resorts. Like most of these groups, ultimate power rests in the hands of one man at the very top, the oligarch Vladimir Potanin.

Zelenin is now vice-chairman of the Russian Sports Commission. Sergey works for him in a newly-launched marketing and publicity department. Zelenin is a very important man.

Will we be interviewing Zelenin or will he be interviewing us, I wonder?

But that’s why the three of us are sitting in the anteroom to his office in the Ministry of Sports.

The ministry is located in the grounds of a nineteenth-century building that once belonged to a Russian count. The inside of the main building is entirely perfunctory and the whole ministry gives the impression that it has just requisitioned this place for a brief stay and will be moving somewhere else just as soon as it can. In fact, the only give-away that we are in the Sports Ministry at all is the huge amount of very conspicuous security.

Not wanting to be late for such an important meeting, we had over-compensated by arriving half an hour early. We killed time by strolling around the slightly ramshackle complex of courtyards and gardens. There’s some half-hearted renovation work going on, which means that parts of the rambling compound look a bit dilapidated and mournful.

Our leisurely progress was monitored by a combination of green-uniformed guards and a variety of very hard-looking plain-clothes guys. The latter seemed to be everywhere, peering through windows, lurking around corners or standing like statues in the middle of one of the colonnaded mini-courtyards scattered through the grounds. They stared at us through plumes of smoke that trailed from the cigarettes they always seemed to be holding - as much a part of the equipment as the guns bulging in the breasts of their suits.

In the middle of the main courtyard, a dozen men in blue army camouflage were guarding and loading a twenty-tonne articulated truck. Grigori translated the Cyrillic lettering on the side. ‘Extraordinary Situations Ministry - For the Serbs of Kosovo.’

The translation brought a swell of further questions to my lips, but our curiosity was deterred by one of the guys in the snazzy blue camouflage gear turning round and scowling at us in a very meaningful way. We continued our stroll in a different direction.

The contrast with the rest of what I’d seen in Moscow could not be sharper. Yes, most of the banks and money change places have an armed guard at the door. But their presence now has a somewhat token feel to it like the security desks in offices back home, and the pervasive criminal violence of the 1990s seems to have passed. The police spend most of their time trawling the streets in search of the new enemy. Several times already I’ve seen a hapless Armenian or Azerbaijani being led away protesting to the back of a van.

But here in the Ministry it feels like I’m on the set of a James Bond film. It’s a Russian trait I’ll come to know well during my stay here. Just when I start to readjust my perception of the place, it springs back with a rabbit punch!

Waiting for Zelenin to see us, Grigori and I fiddle nervously with our recording equipment which comprises a MiniDisc player and a couple of mikes. Designed for kids to listen to their favourite pop tracks, the technology has taunted and occasionally baffled two grown men.

We’re all dressed in our Sunday best. I’m wearing the only suit and tie I’ve brought with me for the trip. Ditto Grigori. Sergey is outdoing us with an expensive-looking suit and a genuine Italian designer tie. Everyone in the Ministry is wearing Italian designer ties. That’s because Dmitri Zelenin wears Italian designer ties.

Apparently Zelenin can tell a man’s long-term prospects by what he’s wearing. That’s what he told the glossy magazine Mercury anyway. There was a big profile of Zelenin in an issue lying in Sergey’s flat. Lots of pictures of him dressed in expensive-looking clothes, sitting inside one or another of his prized collection of antique cars. He was the first Russian to own a Bentley, apparently. He also collects horses - he’s a fine judge of them, according to the Russian equivalent of Hello. Every morning when he gets up, he doesn’t like to spend too much time thinking what to wear, so normally he chooses all his clothing each day from one designer - Armani one day, Gucci the next.

A bit like me then… but without the Italian brands. Also, like me, he’s forty years old. But that, sadly, is the end of what we’ve got in common. Unlike me, he’s already overseen the turnaround of two major Russian companies, dragging both from the brink of bankruptcy to profitability. The first was the old Soviet car company ZIL and the second was Norilsk Nickel.

Also unlike me, he appears to be running a government ministry, although why he wouldn’t want to spend more time driving his cars and riding his horses is something of a mystery to me. Grigori’s response is that Zelenin is being groomed by the Interros Group for something very special - a governorship of a territory, maybe even (Grigori’s eyes widen at this point) prime minister!

After what seems ages but is probably only five minutes, a tall muscular woman with peroxide hair abruptly opens the door to let us into Zelenin’s office.

The room is dominated by a large board table, or maybe that should be committee table, with enough space to sit twenty people. The walls are whitewashed and there is little excess furniture, reinforcing the impression that there’s a certain impermanence to the Ministry’s stay here.

After brief introductions and an exchange of cards…

Dmitry V. Zelenin

Deputy Chairman

The State Committee of Russian Federation for Physical Culture and Sport

… Zelenin sits on one side with the powerfully-built blonde - his PA as it turns out - with the three of us sitting opposite him on the other side.

Zelenin looks younger than his age. He has film-star good looks, a square jaw and dark intelligent eyes. He’s very smartly dressed but in a calculatedly understated way. You know his suit costs a lot of money but there’s nothing flash about it. Same with the tie. It’s as if someone very rich is trying to dress down.

He’s an immediately likeable man. Also, unlike many senior Russian officials, he’s a very approachable man. The interview is not pre-arranged, with the submission of written questions,