11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Glagoslav Publications B.V.

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

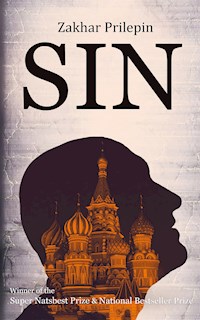

Sin

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 296

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

ZAKHAR PRILEPIN

SIN

Glagoslav Publications

SIN

By Zakhar Prilepin

First published in Russian as “Гpex”

Translated by Simon Patterson

with Nina Chordas

Edited by Nina Chordas

© Zakhar Prilepin 2008

Represented by www.nibbe-wiedling.com

© 2012, Glagoslav Publications, United Kingdom

Glagoslav Publications Ltd

88-90 Hatton Garden

EC1N 8PN London

United Kingdom

www.glagoslav.com

ISBN 9789491425370

This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Contents

Whatever day of the week it happens to be

Sin

Karlsson

Wheels

Six cigarettes and so on

There won’t be anything

The White Square

In other words…

Poems by Zakharka

Failed sonnet

White dreams

Dance

Concert

The Sergeant

Whatever day of the week it happens to be

My heart was absent. Happiness is weightless, and its bearers are weightless. But the heart is heavy. I had no heart. She had no heart either, we were both heartless.

Everything around us had become wonderful; and this “everything” sometimes seemed to expand, and sometimes froze, so that we could enjoy it. We did enjoy it. Nothing could touch us to the extent that it evoked any other reaction but a good, light laughter.

Sometimes she went away, and I waited. Unable to sit waiting for her at home, I reduced the time before our meeting and the distance between us, and went out into the yard.

There were puppies running around in the yard, four of them. We gave them names: Brovkin – a tough tramp with a cheerful nature; Yaponka – a slanty-eyed, cunning, reddish puppy; Belyak – a white runt, who was constantly trying to compete with Brovkin and always failing; and finally, Grenlan – the origin of her name was a mystery, and it seemed very suitable for this princess with sorrowful eyes, who piddled out of fear or adoration the minute anyone called her.

I sat on the grass surrounded by the puppies. Brovkin was lounging around on the ground not far away, and every time I called him, he energetically nodded to me. “Hello,” he said. “It’s great, isn’t it?” Yaponka and Belyak fussed about, rubbing their noses in the grass. Grenlan was lying next to them. Every time I tried to pet her, she rolled on her back and squeaked: her entire appearance said that, although she had almost limitless trust in me, even revealing her pink belly, she was still so terrified, so terrified that she didn’t have the strength to bear it. I was seriously worried that her heart would burst from fear. “Hey, what’s wrong with you, darlin’!” I said to reassure her, looking with interest at her belly and everything that was arranged on it. “What a girl!”

I don’t know how the puppies got into our courtyard. One time in the morning, incredibly happy even while asleep, calmly holding in my hands the heavy, ripe adornments of my darling, who was sleeping with her back to me, I heard the resonant sound of puppies barking – as if the little dogs had made the inexplicable things inside me material, and had clearly expressed my mood with their voices. Although, when I was first awakened by the puppies’ noise, I was angry – they’d woken me up, and they could have woken up my Marysya too: but I soon realized that they were not barking just to bark, but were begging food from passers-by – I heard their voices too. They usually yelled at them to go away: “I don’t have anything, get lost! Shoo! Get lost!”

I pulled on my jeans, that were lying around in the kitchen – we constantly got carried away and reeled around the apartment, until we were completely exhausted, and only in the morning, smiling rather foolishly, we traced our torrid paths by the pieces of furniture that we had displaced or knocked over, and by other inspired chaos – anyway, I pulled on my jeans and ran outside in the flip-flops which for some unknown reason I associated with my happiness, my love and my wonderful life.

The puppies, having failed to elicit any food from the succession of passers-by, tirelessly nosed around in the grass, digging up bits of rubbish, fighting over twigs and a piece of dry bone, time and again turning over an empty can – and naturally, this couldn’t fill them up. I whistled, and they came running over to me – oh, if only my happiness would come running to me like this throughout my life, with this furious readiness. And they circled me, incessantly nuzzling against me, but also sniffing at my hands: bring us something to eat, man, they said with their joyful look.

“Right, folks!” I said and ran home.

I lunged at the fridge, opened it, knelt prayerfully before it. With my hand I tousled and stroked Marysya’s white knickers, which I had picked up from the floor in the corridor, without of course being surprised as to how they had got there. The knickers were soft; the fridge was empty. Marysa and I were not gluttons – we just never really cooked anything, we had a lot of other things on our minds. We didn’t want to be substantial like borshch, we fried large slabs of meat and immediately ate them, or, smearing and kissing each other, we whipped up egg-nog and drank that straight away too. There was nothing in the fridge, just an egg, like a viewer who had fallen asleep, in the cinema, surrounded by empty seats on both sides: above and below. I opened the freezer and was glad to discover a box of milk in it. With a crack, I ripped this box from its ancient resting-place, rushed to the kitchen and was happy once again to find flour. A jar of sunflower oil stood peacefully on the windowsill. I’ll make pancakes for you!

Twenty minutes later I had made ten or so deformed specimens, raw in some places, burnt in others, but quite edible – I tried them myself and was satisfied. Jumping down two steps at a time, feeling in my hand the heat of the pancakes, which I had put in a plastic bag, I flew out of the building. While descending the stairs I worried that the puppies might have run away, but I was reassured as soon as I heard their voices.

“What wonderful pups you are!” I exclaimed. “Let’s try the pancakes!”

Out of the bag I extricated the first pancake, which was balled up like all the rest. All four puppies opened their young, hot mouths at once. Brovkin – who got this name later – was the first to take a hot mouthful, pushing the others aside. It burned his mouth and he immediately dropped it, but he didn’t leave it there, dragging it in several movements by half a meter into the grass, where he hurriedly bit it around the edges, then, shaking his head, swallowed it and came leaping back to me.

Waving the pancakes in the air to cool them down, I carefully gave each puppy a separate piece, though the mighty Brovkin managed to swallow both his own piece and to take pieces from his young relatives. However, he did this inoffensively, without humiliating anyone, as if he were fooling around. The puppy which we later called Grenlan got the fewest pancakes of all, and after a couple of minutes, when I’d learned to tell the puppies apart – they initially seemed indistinguishable – I started to shoo the pushy, fluffy-browed brothers and cunning red-furred sister away, so no one could snatch her sweet piece of pancake from this touching little creature, bashful even in her own family.

Thus, we became friends.

Every time I lied to myself shamelessly that a minute before my darling arrived, before she turned the corner, I could already sense her approach – something moved in the thickening blue air, somewhere an auto braked. I was already smiling like a fool, even when Marysya was still a long way off, thirty meters or so, and I couldn’t stop smiling, and commanded the puppies: “Right then, let’s meet my darling, quick! Do I feed you pancakes for nothing, you spongers!”

The puppies jumped up and, waggling their fluffy bodies, tripping from happiness, they ran to my darling, threatening to scratch her exquisite ankles. Marysenka stepped over them and comically shooed the puppies away with her little black purse. Everything inside me was trembling and twirling, like puppy tails. Still fending them off with her purse, Marysenka wandered over to me, sat down with flawless elegance, and inclined her cool, fragrant, pebble-smooth neck, so that I could kiss it. In the instant that I kissed her, she moved away by a fraction of a millimeter, or rather shuddered – of course, I hadn’t shaved. I hadn’t found the time to do so all day – I was busy: I was waiting for her. I couldn’t take my mind off her. Marysya took one of the puppies with both hands and looked it over, laughing. The puppy’s belly showed pink, and three hairs stuck out, sometimes with a tiny white drop hanging from them.

“Their mouths smell of grass,” Marysya said and added in a whisper: “green grass.”

We left the puppies to play together, and went to the shop, where we bought cheap treats, annoying the saleswomen with the huge amount of spare change that Marysya dug out of her bag, and I took out of my jeans. Often, the irritated saleswomen didn’t even count the change, but disdainfully scooped it up and poured it into the angular cavity of the cash register, not the section for the copper coins, but the “white” coins – the ones worth one kopeck and five kopecks, which had completely lost any purchasing power in our country, as it cheerfully slid into poverty. We laughed, no one’s disdainful irritation could belittle us.

“Notice how today doesn’t seem like a Tuesday,” Marysya observed as we left the shop. “Today feels like Friday. On Tuesdays, there are far fewer children outdoors, the girls aren’t dressed so brightly, the students are busier and the cars aren’t so slow. Today time has definitely shifted. Tuesday has turned into Friday. What will tomorrow be, I wonder?”

I was amused at her intentionally bookish language – this was one of the things we did for fun, to talk like this. Later our speech became ordinary human speech – incorrect constructions, interjections, hints and laughter. None of this can be reproduced – because every phrase had a story behind it, every joke was so charming and fundamentally stupid that another repetition would kill it dead, as though it was born a fragile flower that immediately started to wilt. We spoke in the normal language of people who are in love and happy. They don’t write like that in books. I can only single out a few individual phrases. For example this one:

“I visited Valies,” Marysya said. “He proposed that I get married.”

“To him?”

What a stupid question. Who else?

…The actor Konstantin Lvovich Valies was an old, burly man with a heavy heart. His heart was probably no longer beating, but rather sinking.

His mournful Jewish eyes under heavy, caterpillar-like eyelids had completely lost their natural cunning. With me, as with a youth, he still kept his poise – he was bitterly ironic, as it seemed to him, and frowned patronizingly. With her, he could not conceal his vulnerability, and this vulnerability appeared as a bare white stomach under a badly tucked-in shirt.

Once, as someone who does anything to earn money as long it’s legal, including writing the stupid rubbish which usually serves to fill up newspapers, I asked Valies for an interview.

He invited me to his home.

I arrived a little earlier, and blissfully smoked on a bench by the house. I rose from the bench and went to the entranceway. Glancing at my watch, and seeing that I had another five minutes, I went back to the swings that I had just walked past, and touched them with my fingers, feeling the cold and roughness of the rusty iron bars. I sat on a swing and pushed off gently with my legs. The swing gave a light creaking noise. It seemed familiar to me, reminding me of something. I rocked on the swing again and heard quite clearly: V-va… li… es… I rocked on the swing again. “Va-li-es” – the swing creaked. Va-li-es. I smiled and jumped off rather clumsily – at my back, the swing shrieked out something with an iron hiss, but I couldn’t tell what it was. The door of the entranceway muttered something in the same tone as the swing.

I forgot to say that Valies was a senior actor at the Comedy Theater in our town; otherwise there would have been no reason for me to visit him. No one asked me who I was through the door when I knocked – in the best of Soviet traditions, the door opened wide, and Konstantin Lvovich smiled.

“Are you the journalist? Come in…”

He was short and thick-set, his abundantly wrinkled neck showed his age, but his impeccable actor’s voice still sounded rich and important.

Valies smoked, shaking off the ash with a swift movement, gesticulated, raised his eyebrows and kept them there just a tad longer than an ordinary person, who was no artist, could. But this all suited Konstantin Lvovich – the raised eyebrows, the glances, the pauses. As he talked, he deployed all of this skillfully and attractively. Like chess, in a definite order. And even his cough was artistic.

“Excuse me,” he always said when he coughed, and where the sound of the last syllable of “Excuse me” ended, the next phrase would immediately continue.

“So then… Zakhar, right? So then, Zakhar…” – he would say, carefully pronouncing my somewhat rare name, as if he were tasting it with his tongue, like a berry or a nut.

“Valies studied at the theatrical academy with Yevgeny Yevstigneev, they were friends!” I repeated to Marysenka that evening what Konstantin Lvovich himself had said to me. Yevstigneev in a dark little room with a portrait of Charlie Chaplin by his squashed bed – the young and already bald Yevstigneev, living with his mother who quietly fussed behind the plywood wall, and Valies paying him a visit, curly-haired, with bright Jewish eyes… I imagined all this vividly to myself – and in rich colors, as if I had seen it myself, I described it to my darling. I wanted to surprise her, I liked surprising her. And she enjoyed being surprised.

“Valies and Yevstigneev were the stars of their year, they were such a cheerful pair, two clowns, one with curly hair and the other bald, a Jew and a Russian, almost like Ilf and Petrov. Just fancy that…” I said to Marysya, looking into her laughing eyes.

“What happened after that?” Marysya asked.

After he graduated from the academy, Zhenya Yevstigneev wasn’t accepted into our Comedy Theater – they said that they didn’t need him. But Valies was accepted immediately. Also, he started to appear in films, at the same time as Yevstigneev, who moved to Moscow. In the space of a few years, Valies played the poet Alexander Pushkin three times and the revolutionary Yakov Sverdlov three times as well. The films were shown all over the country… Valies also played a harmless Jew in a war film, together with Shura Demyanenko, who was famous at the time. And then he played Judas in a film where Vladimir Vysotsky played Christ. Although, truth to say, work on this film was stopped before shooting ended. But on the whole, Valies’ acting career got off to a very lively start.

“…But then they stopped putting Valies into films,” I said to Marysya.

He waited for an invitation to appear in another film, but it never came. So he didn’t become a star, although in our town, of course, he was almost considered one. But theater productions came and went and were forgotten, and his obscure films were also forgotten, and Valies got old.

In conversation, Valies was ill-tempered, and swore. It was good that way. It would have been very sad to look at an old man with a sinking heart… The smoke dispersed, and he lit another cigarette – with a match, for some reason, there was no lighter on the table.

His time was passing, and was almost gone. Somewhere, once, in some distant day, he had been unable to latch on, to grasp something with his tenacious youthful fingers that would enable him to crawl out into that space bathed in warm, beery sunshine, where everyone is granted fame during their lifetime and promised love beyond the grave – perhaps not eternal love, but such that you wouldn’t be forgotten at least for the duration of a memorial drinking party.

Valies crushed the next cigarette into the ash tray, waved his hands, and the yellow tips of his fingers flashed by – he smoked a lot. He held in the smoke, and as he slowly exhaled, he became lost in the smoke, not squinting his eyes, throwing his head back. It was clear that everything was fading away, and now the whites of his eyes were shining amid the pink veins, and his big lips were moving, and his heavy eyelids were trembling….

“Do you feel sorry for him, Marysenka?”

The next day I typed up the interview, read it over and took it to Valies. I handed it over and scurried off. Valies saw me off tenderly. And rang me up as soon as I was barely home. Perhaps he had started ringing earlier – the call arrested me just as I entered the apartment. The actor’s voice was trembling. He was extremely angry.

“The interview can’t appear in this form!” he almost shrieked.

I was somewhat taken aback.

“All right then, it won’t,” I said as calmly as possible.

“Goodbye!” he said curtly, and slammed the receiver.

“What did I do wrong?” I wondered.

Every morning, we were woken by barking – the puppies continued to beg for food from passers-by on their way to work. The passers-by cursed them – the puppies dirtied their clothes with their paws.

But once on a deep morning that merged into noon, I did not hear the puppies. I felt anxious while I was still asleep: something was obviously lacking in the languid confusion of sounds and reflections that precede awakening. An emptiness arose, it was like a funnel that was sucking away my sleepy peace.

“Marysenka! I can’t hear the puppies!” I said quietly, and with such horror as if I couldn’t find the pulse on my wrist.

Marysenka was terrified herself.

“Quick, run outside!” she also whispered.

A few seconds later, I was jumping down the steps, thinking feverishly: Did a car run them over? What, all four of them? That can’t be… I ran into the sun and into the scent of warmed earth and grass, and the quiet noises of a car around the corner, and whistled, and shouted, repeating the names of the puppies one after another and then at random. I circled the untidy yard, overgrown with bushes. I looked under each bush – but didn’t find anyone there.

I ran around our incredible building, incredible because on one side it had three stories, and on the other it had four. It was situated on a slope, and so the architects decided to make the building multi-levelled – so that the roof would be even; the building could easily drive insane an alcoholic who was attempting to judge how far off he was from the D.T.s by counting the number of stories in this decrepit but still mighty “Stalin-era” building.

I thought about this briefly again as I walked around the building slowly, banging on the water pipes for some reason, and looking into the windows. There were no puppies, nor any traces of them.

Terribly upset, I returned home. Marysya immediately understood everything, but still asked:

“No?”

“No.”

“I heard someone calling them in the morning,” she said. “That’s right, I did. It was some guy with a hoarse voice.”

I looked at Marysya, my whole appearance demanding that she remember what he said, this guy, and how he talked – I would go and find him in the town by his voice, and ask him where my puppies were.

“The tramps probably took them,” Marysya said resignedly.

“What tramps?”

“A whole family of them lives not far from here, in a Khrushchev-era building. A few men and a woman. They often walk back past our home with rubbish bags. They probably lured the puppies to go with them.

“Do you mean… they could eat them?”

“They eat anything.”

For a moment I pictured this all to myself – how my jolly friends were lured by deceit and thrown in a bag. How they squealed as they were carried. How happy they were when they were dumped out of the bag in the apartment – and at first the puppies even liked it: the delicious smell of tasty, rotting meat and… what’s that other smell? Stale alcohol…

Perhaps the tramps even played with the puppies a little – after all, they’re people too. They may have stroked their backs and tickled their tummies. But then came dinner time… They couldn’t have butchered them all at once? I thought, almost crying. Maybe two… maybe three. I imagined these agonizing pictures, and I even started shaking.

“Where do they live?” I asked Marysenka.

“I don’t know.”

“Who does?”

“Maybe the neighbors do?”

Silently I put my shoes on, thinking what weapon to take with me. There wasn’t any weapon in the house apart from a kitchen knife, but I didn’t take it. If I stab a tramp or all the tramps with this knife, then I’ll have to throw it away, I thought gloomily. I went around the neighbors’ apartments, but most of them had already gone to work, and those who were at home were mainly elderly, and couldn’t understand what I wanted from them – something about puppies, something about tramps… Besides, they didn’t open their doors to me. I got sick of explaining things to the peepholes of wooden doors which I could knock down with three or so kicks. After calling one of the neighbors an “old moron,” I ran out of our building, and headed to the building where the tramps lived.

I reached the Khrushchev-era building, almost running, and as I approached it I tried to determine which was the ill-fated tramps’ den by looking at the windows. I couldn’t work it out; there were too many poor and dirty windows, and only two that were clean. I ran into the building and rang the doorbell of apartment №1.

“Where do the tramps live?” I asked.

“We’re tramps ourselves,” a man in his underpants replied sullenly, looking me over. “What do you want?”

I looked over his shoulder, foolishly hoping that Brovkin would jump out to meet me. Or the pitiful Grenlan would crawl out, dragging intestines behind her. The apartment was dark, and there was a bicycle in the entry. Twisted and dirty doormats lay on the floor. The door to apartment №2 was opened by a woman from the Caucasus, and several swarthy kids came running out. I didn’t bother explaining anything to them, although the woman immediately started talking a lot. I didn’t understand what she was talking about. I went up to the second floor.

“There’s an apartment with tramps living in it in your building,” I explained to a tidy-looking old woman, who was coming down the stairs. “They robbed me, and I’m looking for them.”

The old woman told me that the tramps lived in the next entranceway on the second floor.

“What did they steal?” she asked, as I was already going down the stairs.

“My bride,” I was going to joke, but I thought better of it.

“This one thing…”

I looked around outside – perhaps there was some blunt instrument I could take. There wasn’t any to be found, or I would have taken one. I didn’t try to break a branch off the American maple tree growing in the yard – you couldn’t break it if you tried, you could spend a whole week bending the soft, fragile branch, and it wouldn’t do any good. It’s a wretched, ugly tree, I thought vengefully and angrily, somehow linking the tramps with American maples and America itself, as if the tramps had been brought over from there. The second floor – where should I go? This door, probably. The one that looks the worst. As if people had been pissing on it for several years. And it’s splintered at the bottom, revealing the yellow wood.

I pressed the door bell, stupidly. Yes, that’s right, it will ring out with a trill, just press it harder. For some reason I wiped my finger on my trousers, having touched a doorbell that had been silent for one hundred years, and didn’t even have wires attached to it. I listened to the noises behind the door, hoping of course to hear the puppies.

Have you already devoured them, you skunks?… I’ll show you…

For an instant I contemplated what to hit the door with – my fist or my foot. I even raised my foot, but then hit it with my fist, not very hard, and then harder. The door opened with a hiss and a creak, just by a crack. I pushed the door with my hands – it dragged across the floor, over a worn track. I stepped into semi-darkness and a nauseating smell, firing myself up with a bitterness that simply wilted from the stench.

“Hey!” I called, willing my voice to sound rough and harsh, but the call came out stifled.

What should I call them? ‘Hey, people’, ‘Hey, tramps’? They’re not actually tramps, if they have a place of residence.

I examined the floor, for some reason convinced that I would put my foot into slimy filth if I took another step. I took a step. The floor was firm. The kitchen was to the left, and to the right was a room. I felt sick. I let a long line of spit, the precursor to vomit, out of my mouth. The line of spit swayed, fell and hung on the wall that was covered with wallpaper that was ripped in the form of a peak.

Why is the wallpaper in these apartments always ripped? Do they rip it on purpose or something?

“What are you spitting for?” a hoarse voice asked. “You’re in a house, you fuck.”

I couldn’t tell at first whether the voice was a man’s or a woman’s. And where was it coming from – the room, or the kitchen? I wasn’t visible from the room, so it must be from the kitchen. It was also dark in the kitchen. As I looked in, I realized that the windows were covered with sheets of plywood. I took another step towards the kitchen, and saw a person sitting at the table. The sex of the person was still unclear. A lot of disheveled hair… Barefoot… Pants, or something like pants, which ended above the knees. It seemed that there was a wound on the person’s bare leg. And something was writhing in the wound, in a large quantity. Maybe I just imagined it in the dark.

There were a lot of bottles and cans on the table.

We were silent. The person wheezed, not looking at me. Suddenly, the person coughed, the table shook and the bottles chimed. The person coughed with all his insides, his lungs, bronchi, kidneys, stomach, nose, every pore. Everything inside him rumbled and seethed, spraying mucus, spit and bile around him. The sour air in the apartment slowly moved and thickened around me. I realized that if I took a single deep breath, I would catch several incurable diseases, which would in short order make me a complete invalid with pus-filled eyes and uncontrollable bloody diarrhea.

I stood to attention, without breathing, in front of the coughing tramp, as if he were a general giving me a dressing-down. The coughing gradually died down, and in conclusion, the tramp spat out a long trail of spit on to the floor, and wiped his mouth with his sleeve. Finally, I decided to go into the kitchen.

“I’ve come for the puppies!” I said loudly, almost choking, because as I opened my mouth, I did not breathe. My words sounded wooden. “Hey you, where are the puppies?” I asked with a last gasp: it was as if my shoulder had hit a pile of wood and several logs had rolled off it, dully thumping to the ground.

The person looked up at me and coughed again. I almost ran into the kitchen, scared that I would fall unconscious and would lie here, on the floor, and these vermin would think that I was one of them, and put me to lie with them. Marysenka would come and see me lying next to tramps. I kicked the bare legs of the tramp, that were in my way, and it looked as if several dozen little midges flew up off the wound on his ankle.

“Damn it!” I cursed, breathing heavily, no longer able to hold my breath. The person I had kicked swayed and fell over, taking the bottles on the table with him, and they fell on him, and the chair that he was sitting on also fell over, with two legs stuck in the air. And they were not positioned diagonally, but on the same side. It couldn’t stand up! You can’t sit on it! I thought, and shouted:

“Where are the puppies, scum?!”

The person squirmed about on the floor. Something trickled under my shoes. I tore the plywood board from the window, and saw that the window was partially smashed, and so this was evidently why it had been covered over. In the window, between the partitions, there was a half-liter bottle containing a solitary limp pickle covered in a white beard of mold that Father Christmas could have envied.

“Damn it! Damn!” I cursed again, helplessly looking over the empty kitchen, in which several broken crates were lying around in addition to the upside-down chair. There was no gas stove. A tap was leaking in the corner. In the sink lay a mound of half-rotten vegetables. All kinds of creatures with feelers or wings were crawling over the vegetables.

I jumped over the person lying on the floor and raced into the room, almost falling over the clothes piled on the floor – coats, jackets, rags. Perhaps someone was lying under the rags, huddled there. The room was empty, there was just an old television in the corner, with the picture tube intact. The window was also covered over with plywood boards.

“Who do you think you are!” the voice shouted to me from the kitchen. “I’m a boxer, asshole.”

“Where are the puppies, boxer-asshole?” I mocked him, but didn’t go back to the kitchen. Instead, overcoming my squeamishness, I opened the door to the toilet. There was no toilet bowl: just a gaping hole in the floor. In the bath, as yellow as lemonade, there were shards of glass and empty bottles.

“What puppies?” the voice shouted again, and added several dozen incomprehensible noises resembling either complaining or swearing.

The voice definitely belonged to a man.

“Did you take the puppies?” I shouted at him, leaving the toilet and looking for something in the corridor to hit him with. For some reason I thought there should be a crutch here, I thought I had seen one.

“Did you eat the puppies? Talk! Did you eat the puppies, you cannibals?” I screamed.

“You ate them yourself!” he shouted in reply.

I picked up a long-collapsed coat rack from the floor, threw it at the man lying in the kitchen and began to look for the crutch again.

“Sasha!” the tramp called to someone. He was still squirming, unable to stand up.

“Crack!” the bottle he threw at me clanked against the wall.

“Thief!” sobbed the man writhing on the floor, looking for something else to throw at me.

He had obviously cut himself on something – blood was streaming profusely from his hand.

He threw an iron mug at me, and another bottle. I managed to avoid the mug, and comically kicked the bottle away.

OK, that’s enough… I thought and ran out of the apartment. In the entryway I checked to make sure that there was no slimy mud on me. It didn’t look like it. The air hit me from all sides – how wonderful and clean the air is in entryways, my God. A trail of murky and sour filth, almost visible, crawled towards me from the tramps’ den – and I ran down to the first floor, madly smiling about something.

I could hear shouts still coming from the apartment on the second floor.

“They were also children once,” Marysya said to me back home. “Imagine how they ran around with their pink bellies…”

“They were,” I replied without thinking, not having firmly decided whether they were or not. I tried to remember the face of the man in the kitchen, but couldn’t.

When I got home I got into the bath and scrubbed myself with a sponge for a long time, until my shoulders turned pink.

“They couldn’t have eaten them in one morning? They couldn’t, could they?” Marysenka asked me loudly from behind the door.

“No, they couldn’t!” I replied.

“Perhaps they were taken away by other tramps?” Marysya suggested.

“But they should have squealed,” I thought out loud. “Wouldn’t they have whined when they were thrown into the sack? We would have heard them.”

Marysenka fell silent, evidently thinking to herself.

“Why are you taking so long? Come to me!” she called, and by her voice I understood that she hadn’t reached any definite conclusion about the puppies’ fate.

“You come to me,” I replied.

I stood up in the bath, scattering foam from my hands on to the floor, and reached for the latch. Marysya stood by the door and looked at me with merry eyes.

For an hour we forgot about the puppies. I thought with surprise that we had been together for seven months, and every time – and we had probably done this several hundred times now – every time it was better than the last. Although the last time it seemed that it couldn’t be better.

What can this be? I thought, moving my hand across her back, which incredibly narrowed at the waist and merged into a white magnificence, just left by me. It was covered with pink spots, I had rumpled it so thoroughly.

My hand became limp, although a minute ago it had been firm, and had tenaciously, painfully clutched the cheekbones of my darling’s face – when I was behind her, I loved looking at her – and I turned her face towards me: to see what was there in her eyes, to look at her lips…

We were coming back from the shop almost two weeks later – we had probably buried them in our minds during this time, although we didn’t talk about it out loud – and they reappeared. The puppies, as though nothing had happened, flew out to meet us and immediately scratched up the beautiful legs of my darling and left traces of their cheerful paws on my beige jeans.

“Guys! You’re alive!” I shouted, lifting them all up in turn and looking into the puppies’ foolish eyes.

Last of all, I tried to take Grenlan into my arms, but as usual she immediately rolled on to her back, revealing her stomach, and puffed herself up either out of fear or happiness, or out of endless respect for us.

“Give them something!” Marysenka ordered.

I couldn’t give them raw, frozen dumplings, and so I opened the yoghurt, pouring the pink substance right on to the crumpled asphalt. They licked it all up and started running around us in circles, around Marysya and me, and every time they circled they rubbed their noses in the dark marks left by the yoghurt that had instantly vanished.

“Give them some more!” Marysya said, smiling with her eyes.

We fed the puppies four yoghurts and went home happily, talking about where the puppies had vanished for so long. We didn’t work it out, of course.

The puppies settled into our yard again.

Summer came to a full boil outside, steaming and trembling, and when we opened the window in the morning, we could call out to the puppies, who ran around in circles, unsure who was calling them, but very happy about the chicken bones that fell from the sky.