Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arc Publications

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: New Voices from Europe and Beyond

- Sprache: Englisch

Six Finnish Poets continues Arc's profiling of some of the 'smaller' languages of Europe and beyond, showcasing their beautiful and unusual literary stylings to audiences closer to home. Here six poets from Finland offer up a refreshing mix of narrative, cinematic and experimental devices, ranging from whimsy to sci-fi to punk. The poets featured are: Vesa Haapala, Janne Nummela, Matilda Södergran, Henriikka Tavi, Juhana Vähänen and Katariina Vuorinen. This is a bilingual edition, with the Finnish original and the English translation on facing pages. Translated by Lola Rogers, Emily Jeremiah and Helen R. Boultrum . Teemu Manninen is a poet and literary critic based in Tampere, Finland. His books include five poetry collections. He works as a producer for the Helsinki Poetics Conference, an editor for the poetry publisher Osuuskunta Poesia, and a poetry reviewer for the Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat. This title is also available from Amazon as an eBook.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 174

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SIX FINNISH POETS

Published by Arc Publications

Nanholme Mill, Shaw Wood Road

Todmorden, OL14 6DA, UK

www.arcpublications.co.uk Copyright in the poems © individual poets as named, 2013

Copyright in the translations © translators as named, 2013

Copyright in the Introduction © Teemu Manninen, 2013

Copyright in the present edition © Arc Publications, 2013 Design by Tony Ward ISBN (pbk): 978 1906570 88 0

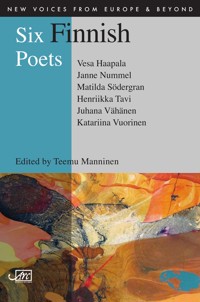

ISBN (ebk): 978 1908376 53 4 Cover image:

From an original painting by Janne Nummela, by kind permission of the artist. Acknowledgements

The publishers are grateful to the authors and, in the case of previously published works, to their publishers for allowing their poems to be included in this anthology. Arc Publications gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange.

This book is copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Arc Publications Ltd. The ‘New Voices from Europe and Beyond’ anthology series is published in co-operation with Literature Across Frontiers, a platform established with support from the Culture Programme of the EU.

Arc Publications ‘New Voices from Europe and Beyond’

Series Editor: Alexandra Büchler

SIX

FINNISH

POETS

Translated by

Lola Rogers, Emily & Fleur Jeremiah, Helen R. Boultrum

Edited and with an introduction by

Teemu Manninen

2013

CONTENTS

Series Editor’s Preface

Introduction

VESA HAAPALA

Translated by Helen R. Boultrum

Biography

teoksesta Termini

•

from Termini

Alussa

•

In the Beginning

Crown of Sweden

•

Crown of Sweden

Jonkin Hajaannuksen Yhtälö

•

An Equation of the Dissolution of Something

“Kuin kasvi elämän kirjassa…”

•

“Like a plant in the Book of Life…”

Mielenrauhaa CD

•

Inner Calm CD

JANNE NUMMELA

Translated by Lola Rogers

Biography

Näky Rannalta

•

The View from the Shore

“suljen silmäni ja uneksin”

•

“I close my eyes and dream”

“Jokainen tarvitsee elämäänsä mantelin…”

•

“Everyone needs an almond in their lives…”

Anaerobinen Lause

•

Anaerobic Clause

runosta Okeanos

•

from Okeanos

teoksesta Ensyklopedia

•

from Encyclopedia

MATILDA SÖDERGRAN

Translated by Helen R. Boultrum

Biography

dikter ut Deliranten

•

from Delirious

dikter ur Maror (ett sätt åt dig)

•

from She-Mares (a manner for you)

“Upplever dig”

•

“Experiencing you”

“Du är underlig…”

•

“You’re peculiar…”

“En orangutanghona kedjades…”

•

“A female orangutan…”

“Hjärnan plockas…”

•

“A brain is extracted…”

“Vanbruket av ord”

•

“Abuse of words”

“Hela dagen har varit mörk…”

•

“The whole day has been dark…”

“Hett dis…”

•

“Hot haze…”

“Fruktköttet flyter…”

•

“The flesh runs out…”

“Hennes arm uppsvullen…”

•

“Her arm swollen…”

“Du måste fortsätta tänka…”

•

“You’ve got to carry on thinking…”

“Du undrar varför huvudet…”

•

“You wonder why your head…”

HENRIIKKA TAVI

Translated by Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah

Biography

“Tömistelemme jalkojamme…”

•

“We stamp our feet…”

“Jepi kuuluu Mensaan…”

•

“Jepi belongs to Mensa…”

“Jotkin ravuista…”

•

“Some of the crayfish…”

“kaksiviivaisesta…”

•

“a faded swirl…”

“Minä antaisin pois koko sydämeni”

•

“I’d give away my whole heart”

En Siedä Kertomuksia Rakkaudesta

•

I Can’t Stand Stories About Love

Kehtolaulu

•

Lullaby

Kultapuu

•

A Tree of Gold

Lastu

•

The Shaving

Lastu

•

The Shaving

Häiveperhonen

•

The Purple Emperor

Suokirjosiipi

•

The Northern Grizzled Skipper

Mikä Kosketti Minua Tänään

•

What Touched Me Today

Postikortti

•

The Postcard

“Ja hän sanoi minulle kieroja…”

•

“And he said twisted and ruthless things…”

“Esa rakentaa dyynimuodostelman…”

•

“Esa builds a dune formation…”

“Ja seutu…”

•

“And the region we inhabited…”

KATARIINA VUORINEN

Translated by Emily Jeremiah and Fleur Jeremiah

Biography

Kodin ja Laiskuuden Läksyjä

•

Lessons Of Home And Idleness

Otan Kovemmin Kiinni Kuin Muut Rakkaudesta

•

I Seize Love More Tightly Than Others

Ristiäissaatto

•

Baptismal Procession

Koekaniini I

•

Guinea Pig I

Mostarin Unet

•

The Dreams of Mostar

Hääpäivä

•

The Wedding Day

Valkoinen Kohina

•

White Noise

JUHANA VÄHÄNEN

Translated by Lola Rogers

Biography

“vanha mies istuu ohjaajantuolissa…”

•

“an old man sits in a director’s chair…”

Pauliinalle

•

To Pauliina

“Kuinka hän, ajattelen…”

•

“How she, I think…”

“Tätä on runous…”

•

“This is poetry…”

“Kun kiipeän vuorelle…”

•

“When I climb up a mountain…”

“Olen kuten kuka tahansa teini-ikäinen…”

•

“I am like any other teenager…”

“En näe hänen sisäänsä…”

•

“I can’t see inside him…”

About the Editor & Translators

SERIES EDITOR’S PREFACE

Six Finnish Poets is the tenth volume in a series of bilingual anthologies which brings contemporary poetry from around Europe to English-language readers. It is not by accident that the tired old phrase about poetry being ‘lost in translation’ came out of an English-speaking environment, out of a tradition that has always felt remarkably uneasy about translation – of contemporary works, if not the classics. Yet poetry can be, and is, ‘found’ in translation; in fact, any good translation reinvents the poetry of the original, and we should always be aware that any translation is the outcome of a dialogue between two cultures, languages and different poetic sensibilities, between collective as well as individual imaginations, conducted by two voices, that of the poet and of the translator, and joined by a third interlocutor in the process of reading.

And it is this dialogue that is so important to writers in countries and regions where translation has always been an integral part of the literary environment and has played a role in the development of local literary tradition and poetics. Writing without reading poetry from many different traditions would be unthinkable for the poets in the anthologies of this series, many of whom are accomplished translators who consider poetry in translation to be part of their own literary background and an important source of inspiration.

While the series ‘New Voices from Europe and Beyond’ aims to keep a finger on the pulse of the here-and-now of international poetry by presenting the work of a small number of contemporary poets, each collection, edited by a guest editor, has its own focus and rationale for the selection of the poets and poems.

In Six Finnish Poets, we glimpse a nation making full use of the tools of the contemporary moment to develop a fresh poetic voice in the context of a literary activism movement engaging writers and readers alike. Teemu Manninen, in his introduction to this book, refers to “the artificiality of speaking ‘like poets are supposed to speak’”, reminding us of an artifice that is hard to find in the poems that follow. The language, concepts, even the basic grammar of the work of these poets can be bewildering and at times challenging, but they never leave you cold – there are moments of startling beauty, and the translations crackle with the energy of the new. It becomes clear that these writers are as comfortable with a keyboard and touchscreen as they are with the dusty tomes of the poetic tradition – or rather traditions, as this is a nation writing in two languages, Finnish and Swedish – and the resulting poetry has all the diversity and complexity that you might expect from such an amalgam of approaches.

As always, I would like to thank all those who have made this edition possible.

Alexandra Büchler

INTRODUCTION

POETRY AS A FAMILY AFFAIR:

FINNISH CONTEMPORARY POETRY OF THE 2000s

In a paper delivered in the Helsinki Poetics Conference in 2004, the poets Eino Santanen and Aki Salmela wondered why so much of our thinking about poetry is so often preoccupied with the “poet’s mouth”, a set of stylistic, syntactic, figurative and expressive restrictions, which culminates in the artificiality of speaking “like poets are supposed to speak”. In order to write something different, they proposed, we should rid ourself of the “poet’s mouth” and find other ways of communicating with each other.

Santanen and Salmela voiced a common concern that has been, and still is, shared by many of the Finnish poets who have made their debut in the first decade of the twenty-first century. It is a feeling of having been delivered from the necessity of speaking as poets are expected to speak, of having gained a freedom to try on all kinds of costumes, voices and faces, to explore boundaries, to play, frolic, wander and dream of possibilities for literature which are not tied down by definitions of what poetry, or even prose, should be like.

By emphasizing such feelings of deliverance, I am not suggesting that Finnish poets were previously under pressure to conform to an artificial aesthetic, but rather that a certain set of conditions now exists in Finland for the production and reception of poetry that did not exist before, or was at least not understood to be available.

There are three main areas of change. First, there is a growth in new channels of publishing such as publishing co-operatives, self-publishing and the use of the internet. Second, there are new ways of communicating poetry, through the establishment of new literary organizations, through live events (including multimedia events) and through collaborations between poets and practitioners in other creative fields. Finally, there is the realisation that the audience for poetry is divided by age, class, gender, lifestyle and so on into a number of different audiences, and that it is possible to reach these audiences in new and specifically targeted ways.

These three areas of change have given rise to a new discussion culture, a new publicity for poetry and, stemming from this, a new way of writing. To show how these changes have come about, I shall briefly and very schematically describe recent Finnish poetic history.

* * *

Publishing books used to be expensive and difficult. In a small country like Finland – with a population the size of Singapore or Sicily – a marginal literary genre such as poetry never had much of a readership. In the 1980s, when I was growing up, only four (maybe five) major literary publishers dominated the field and this meant that in any given year very few books of poetry appeared. Furthermore, with no tradition of poetry events, very few literary magazines (none of them devoted to poetry), and even fewer reviews of literature of any genre in the press, there was no real possibility for an ongoing discussion between poets or about poetry.

It could be argued that Finnish poetry is really only about fifty years old. Because of the curious nature of the Finnish modernist revolution of the 1950s, which did away with rhyme, metre, subject matter, and even the poetic speech utilized by previous poets, a new way of writing was established, inspired by the kind of modernism exemplified by T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

Of course such things happened elsewhere, but nowhere else in the world was the idea of “making it new” – Ezra Pound’s famous dictum for modern poetry – taken as seriously as it was in Finland. During the 1950s and the 1960s, in practical terms, the history of Finnish poetry was dismantled and discarded in order to invent poetry anew: today, you will not find poetry in metre or rhyme published in Finland. Ours is a curious country; poetry that would be considered avant garde in the English-speaking world is often the boring mainstream in Finland.

This state of affairs is partly the result of a fast pace of change in Finland from the largely rural, agricultural economy of the 1960s to the urban, high-tech boom of the 1990s. In the literary sphere, since the heyday of modernism in the mid-twentieth century, movements, styles and approaches which elsewhere took over a century to evolve, in Finland sped through the decades. During the 1960s, for instance, there was a short period of “arctic hysteria” of happenings, performance art, Dadaism and Surrealism, concrete poetry and weird experimentation, until the 1970s reorganized this energy into various cultural and student movements based on a strict Stalinism and Maoism with a party line of social realism. The ideological bent of those years resulted in a national trauma that the generation of the 60s and 70s is still trying to come to terms with and, in the 1980s, to a dearth of new aesthetic innovation.

* * *

Then, in the 1990s, came a rebirth of poetry, poetry that was in contrast to the political poetry of the 1970s and the standardized free-verse monologue of the 1980s. Helsinki-based poets such as Jyrki Kiiskinen, Helena Sinervo, Riina Katajavuori and Jukka Koskelainen took over the hundred-year-old cultural organization Nuoren Voiman Liitto and the magazine Nuori Voima [Young Power], which became known for importing French post-structuralist theory and associating – for good or ill – poetry with academic literary studies. At the same time they also found new ways of working with publishers and began producing high-profile literary events and series of publications which caught the attention of the media and the reading public.

At the same time in Turku, another kind of renaissance was taking place – a burgeoning of poetry readings and small literary publications, at the forefront of which was the poetry organization Nihil Interit and its magazine Tuli&Savu [Fire&Smoke], established in 1993 by the poets Tommi Parkko and Markus Jääskeläinen. Turku became known for its “street poetry”, verse made for performance, nourished by a diet of staunch naturalism, small publishers, bars, beat and booze, but also a sense of humour and, in general, a lighter tone which the Helsinki Nuori Voima poets did not always share.

If the Helsinki poets showed that poets could work with major cultural institutions in an innovative way, and that poetry could be studied seriously, the Turku poets showed that it could also be a part of everyday life, a way of living, a do-it-yourself activity that was not dependent upon the approval of critics, publishers, or popular opinion.

* * *

The poetry of the 2000s is a combination – frequently a paradoxical and seemingly impossible one – of these two approaches to its form and practice. It is grounded in the work of literary activists all around Finland who belong to many different literary organizations, informal groups and collectives, among them the previously mentioned Nihil Interit and Nuoren Voiman Liitto as well as numerous other groups, most of which have been established in the last ten to fifteen years.

These organisations run the readings, clubs, workshops and conferences where poetry is heard, taught and discussed, such as the Annikki Poetry Festival in Tampere, the Poetry Moon Literary Festival in Helsinki and the Poetry Week in Turku. Along with small communal publishers, such as the highly-regarded co-operative Poesia, Leevi Lehto’s ntamo and Ville Hytönen’s Savukeidas, they publish magazines and books and enlarge the sphere of aesthetic possibility by taking on projects which larger publishers are not willing to tackle.

For such “literary activists” poetry is a part of everyday life, a social community, a subculture which, despite – or perhaps because of – its unapologetic independence is hailed in many quarters as the most exciting thing to have happened in Finnish literature in the last decade. Much of this has been made possible by the fact that publishing has become cheap and the internet has facilitated communication – the making of connections between like-minded people – in a new, more immediate and efficient way. In a country the size of Finland, these connections multiply and networks are quickly formed; ties become very strong, thick with interpersonal dialogue, friendship, rivalry and collaboration. In Finland, poetry is a family affair.

This familial commonality has to be acknowledged if one is to understand the kind of poetry currently being written in Finland: one cannot approach it simply from the viewpoint of major institutions, large publishers, newspapers and literary prizes. Where the best work of an author published by a large publishing house happens to be in a blog, or in a one-off book published by a small publisher, or where a famous poet will only perform rather than appear in print, or where a one-man publishing house (for example Leevi Lehto’s ntamo) publishes more poetry books in a year than all the large publishing houses combined, a more subtle approach is needed in order to situate poets properly in a literary context.

* * *

This is why I have made the selection for this anthology on sociological rather than purely aesthetic grounds. I have used as my basis an encyclopedia of contemporary Finnish poets I co-edited with Maaria Pääjärvi in 2010. We had originally been asked to edit an anthology of ten to fifteen poets representative of the Finnish “poetry boom” (so-called) of the 2000s, but we soon realised that this was highly problematic: there were far too many poets around, the literary scene had gone through numerous changes in the last ten years, and the styles, poetics and subject matter were so diverse that it was impossible to find representative “handfuls” to illustrate everything that had happened and was still happening.

Our solution was to write an encyclopedia that included everyone, in other words all those poets whose debut works had appeared in the first decade of the twenty-first century. It was interesting to see how much they had in common. Born in the 1970s or 1980s with a university education either from Turku, Helsinki or Tampere (with some from Jyväskylä), most poets were connected in some way not only with each other but also with the magazines and literary organisations that make up the Finnish literary scene.

What I personally found most interesting was the fact that I began to see similarities between the social backgrounds and the writing styles of certain individuals. There were the academics, whose take on traditional and experimental forms was tinged with a note of argumentation and critique. There were the ingenious outsiders, who invented new techniques in figurative or actual isolation, and the social experimentalists, who found their sense of irony and humour through collaboration and discussion. There were also the “activists for empathy” who, because of an ethical imperative in their own lives, fought for causes or ways of living, for an expanded consciousness of progressive emancipation.

For someone like me, who had been trained by the academy to look only at the text, it was almost embarrassing to witness how life and work were, in reality, inseparable.

I would like to think that this selection – made with Maaria Pääjärvi, who served as the original editor of this anthology before ceding the task to me – is symbolic of the connection that exists between the life of poetry in Finland and the lives of the poets who write it. It is, at the very least, indicative of the many different styles employed by Finnish poets today, which range from experimental prose to image-rich surrealism, and from sparse, stark minimalism to ironically melancholic references to pop-culture.

Although this anthology is a good start, however, it cannot be regarded in any sense as a complete representation of Finnish contemporary poetry. To deserve this epithet, it would have to take in so much more: the video poets, the visual poets, the sound poets; the modernist traditionalists and the outré experimentalists, the bohemians and the academics; the poets of the 1990s and the poets of the 2000s, not forgetting the older poets who, inspired by the present poetry boom, have had a creative breakthrough in recent years.

Nevertheless I offer this preface as a way of sketching in a background that will help guide you – if only a little – as you leaf through the pages of this book and discover the work of these marvellous poets.

* * *

One could say that the work of VESA HAAPALA is an example of studied, academic poetry – he is not only a poet, but also a university lecturer in Finnish literature in the University of Helsinki – and yet that would be to miss the point completely of his stylistically and thematically broad works. Their range is formidable: from prosaic melancholy on the banks of the river Vantaa to a parody of “shopping mall poetry”, he delivers both engaging satire and formally exquisite set-pieces. His first book of prose poems, Vantaa (2007), delves into local and personal history, while Termini goes to Rome to come to terms with the eternal city. His latest book, Kuka murhasi Ötzin? [Who Murdered Ötzi?], (2012), is a tour-de-force of “experimental confessionalism”, where comic relief is combined with challenging graphic design and formal inventiveness.

JANNE NUMMELA on the other hand is a fine example of the “genius in the wilderness”. He is a Renaissance figure who writes, paints, and composes, and is known for his philosophical omnivoracity, most often on display in his blog ‘Käymälä’. As a poet, he is an inventor: his first book Lyhyellä matkalla ohuesti jäätyneen meren yli [On a Short Trip Over a Thinly Frozen Sea], (2006) was the first book in Finnish to employ internet search engines as a tool for gathering linguistic material, while Medusareaktorit [Medusareactors], (2009) was the first science fiction poetry collection. Ensyklopedia