9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

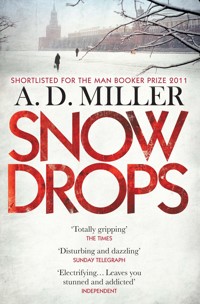

SHORTLISTED FOR THE MAN BOOKER PRIZE 2011 Snowdrops. That's what the Russians call them - the bodies that float up into the light in the thaw. Drunks, most of them, and homeless people who just give up and lie down into the whiteness, and murder victims hidden in the drifts by their killers. Nick has a confession. When he worked as a high-flying British lawyer in Moscow, he was seduced by Masha, an enigmatic woman who led him through her city: the electric nightclubs and intimate dachas, the human kindnesses and state-wide corruption. Yet as Nick fell for Masha, he found that he fell away from himself; he knew that she was dangerous, but life in Russia was addictive, and it was too easy to bury secrets - and corpses - in the winter snows...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

A. D. Miller’s Snowdrops is an intensely riveting psychological drama that unfolds over the course of one Moscow winter, as a young Englishman’s moral compass is spun by the seductive opportunities revealed to him by a new Russia: a land of hedonism and desperation, corruption and kindness, magical dachas and debauched nightclubs; a place where secrets – and corpses – come to light only when the deep snows start to thaw. . .

Snowdrops is a chilling story of love and moral freefall: of the corruption, by a corrupt society, of a corruptible young man. It is taut, intense and has a momentum as irresistible to the reader as the moral danger that first enchants, then threatens to overwhelm, its narrator.

SNOWDROPS

Born in London in 1974, A. D. Miller studied literature at Cambridge and Princeton. He worked as a television producer before joining the Economist. From 2004 to 2007 her was the magazine’s Moscow correspondent, travelling widely across Russia and the former Soviet Union. He is the author of the acclaimed family history The Earl of Petticoat Lane (Wm. Heinemann, 2006); Snowdrops is his first novel. He lives in London with his wife and daughter.

First published in Great Britain in hardback and trade paperback in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © A. D. Miller, 2011

The moral right of A. D. Miller to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84887-452-7 Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-84887-454-1 eBook ISBN: 978-0-85789-303-1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Snowdrop. 1. An early-flowering bulbous plant, having a white pendent flower. 2.Moscow slang. A corpse that lies buried or hidden in the winter snows, emerging only in the thaw.

For Arkady, Becky, Guy, Mark and especially Emma.

I smelled it before I saw it.

There was a crowd of people standing around on the pavement and in the road, most of them policemen, some talking on mobile phones, some smoking, some looking, some looking away. From the way I came, they were blocking my view, and at first I thought that with all the uniforms it must be a traffic accident or maybe an immigration bust. Then I caught the smell. It was a smell like the kind you come home to if you forget to put your rubbish out before you go on holiday – ripe but acidic, strong enough to block out the normal summer aromas of beer and revolution. It was the smell that had given it away.

From about ten metres away, I saw the foot. Just one, as if its owner was stepping very slowly out of a limousine. I can still see the foot now. It was wearing a cheap black slip-on shoe, and above the shoe there was a stretch of grey sock, then a glimpse of greenish flesh.

The cold had kept it fresh, they told me. They didn’t know how long it had been there. Maybe all winter, one of the policemen speculated. They’d used a hammer, he said, or possibly a brick. Not a good job, he said. He asked me if I wanted to see the rest of it. I said no, thank you. I’d already seen and learned more than I needed to during that last winter.

You’re always saying that I never talk about my time in Moscow or about why I left. You’re right, I’ve always made excuses, and soon you’ll understand why. But you’ve gone on asking me, and for some reason lately I keep thinking about it – I can’t stop myself. Perhaps it’s because we’re only three months away from ‘the big day’, and that somehow seems a sort of reckoning. I feel like I need to tell someone about Russia, even if it hurts. Also that probably you should know, since we’re going to make these promises to each other, and maybe even keep them. I think you have a right to know all of it. I thought it would be easier if I wrote it down. You won’t have to make an effort to put a brave face on things, and I won’t have to watch you.

So here is what I’ve written. You wanted to know how it ended. Well, that was almost the end, that afternoon with the foot. But the end really began the year before, in September, in the Metro.

When I told Steve Walsh about the foot, by the way, he said, ‘Snowdrop. Your friend is a snowdrop.’ That’s what the Russians call them, he told me – the bodies that float up into the light in the thaw. Drunks, most of them, and homeless people who just give up and lie down into the whiteness, and murder victims hidden in the drifts by their killers.

Snowdrops: the badness that is already there, always there and very close, but which you somehow manage not to see. The sins the winter hides, sometimes for ever.

| ONE

I can at least be sure of her name. It was Maria Kovalenko, Masha to her friends. She was standing on the station platform at Ploshchad Revolyutsii, Revolution Square, when I first caught sight of her. I could see her face for about five seconds before she took out a little make-up mirror and held it in front of her. With her other hand she put on a pair of sunglasses that I remember thinking she might have just bought from a kiosk in an underpass somewhere. She was leaning against a pillar, up at the end of the platform where the civilian statues are – athletes, engineers, bosomy female farmhands and mothers holding muscular babies. I looked at her for longer than I should have.

There’s a moment at Ploshchad Revolyutsii, a visual effect that happens when you’re transferring to the green line from that platform with the statues. You find yourself crossing the Metro tracks on a little elevated walkway, and on one side you can see a flotilla of disc-shaped chandeliers, stretching along the platform and away into the darkness that the trains come out of. On the other side you see other people making the same journey, only on a parallel walkway, close but separate. When I looked to the right that day I saw the girl with the sunglasses heading the same way.

I got on the train for the one-stop ride to Pushkinskaya. I stood beneath the yellow panelling and the ancient strip lighting that made me feel, every time I took the Metro, as if I was an extra in some paranoid Donald Sutherland film from the seventies. At Pushkinskaya I went up the escalator with its phallic lamps, held open the heavy glass Metro doors for the person behind me like I always used to, and made my way into the maze of low-slung underground passages beneath Pushkin Square. Then she screamed.

She was about five metres behind me, and as well as screaming she was wrestling against a thin man with a ponytail who was trying to steal her handbag (an ostentatiously fake Burberry). She was screaming for help, and the friend who had appeared alongside her – Katya, it turned out – was just screaming. To begin with I only watched, but the man drew back his fist like he was about to punch her, and I heard someone shouting from behind me as if they were going to do something about it. I stepped forward and pulled the thin man back by his collar.

He gave up on the bag and swung his elbows at me, but they didn’t reach. I let go and he lost his balance and fell. It was all over quickly and I didn’t get a good enough look at him. He was young, maybe four inches shorter than me, and seemed embarrassed. He stabbed out a foot, catching me painlessly on the shin, and scrambled to his feet and ran away, down the underpass and up the stairs at the far end that led to Tverskaya – the Oxford Street of Moscow, only with lawless parking, which slopes down from Pushkin Square to Red Square. There were two policemen near the bottom of the steps, but they were too busy smoking and looking for immigrants to harass to pay the mugger any attention.

‘Spasibo,’ said Masha. (Thank you.) She took off the sunglasses.

She was wearing tight tight jeans tucked into knee-high brown leather boots, and a white blouse with one more button undone than there needed to be. Over the blouse she had one of those funny Brezhnev-era autumn coats that Russian women without much money often wear. If you look at them closely they seem to be made out of carpet or beach towel with a cat-fur collar, but from a distance they make the girl in the coat look like the honey-trap in a Cold War thriller. She had a straight bony nose, pale skin and long tawny hair, and with a bit more luck she might have been sitting beneath the gold-leaf ceiling in some hyper-priced restaurant called the Ducal Palace or the Hunting Lodge, eating black caviar and smiling indulgently at a nickel magnate or well-connected oil trader. Perhaps that’s where she is now, though somehow I doubt it.

‘Oi, spasibo,’ said her friend, clasping the fingers of my right hand. Her hand was warm and light. I reckoned the sunglasses girl was in her early twenties, twenty-three maybe, but the friend seemed younger, nineteen or possibly even less. She was wearing white boots, a pink fake-leather miniskirt and a matching jacket. She had a little upturned nose and straight blond hair, and one of those frankly inviting Russian-girl grins, the ones that come with full-on eye contact. It was a smile like the smile of the baby Jesus we once saw – do you remember? – in that church in the village down the coast from Rimini: the old, wise smile on the young face, a smile that said, I know who you are, I know what you want, I was born knowing this.

‘Nichevo,’ I said. (It was nothing.) And again in Russian I added, ‘Is everything okay?’

‘Vso normalno,’ said the sunglasses girl. (Everything is normal.)

‘Kharasho,’ I said. (Good.)

We smiled at each other. My glasses had steamed up in the cloying year-round warmth of the Metro. One of the CD kiosks in the passageway was playing folk music, I remember, the lyrics choked out by one of those drunken Russian chanteurs who sound like they must have started smoking in the womb.

In a parallel universe, in another life, that’s the end of the story. We say goodbye, I go home that afternoon and back to my lawyering the next day. Maybe in that life I’m still there, still in Moscow, maybe I found another job and stayed, never came home and never met you. The girls go on to whoever and whatever it would have been if it hadn’t been me. But I was flushed with that feeling you get when a risky thing goes well, and the high of having done something good. A noble deed in a ruthless place. I was a small-time hero, they’d let me be one, and I was grateful.

The younger one carried on smiling, but the older one was just looking. She was taller than her friend, five nine or ten, and in her heels her green eyes were level with mine. They are lovely eyes. Someone had to say something, and she said, in English, ‘Where are you from?’

I said, ‘I’m from London.’ I’m not from London originally, as you know, but it’s close enough. In Russian I asked, ‘And where are you from?’

‘Now we live here in Moscow,’ she said. I was used to this language game by then. The Russian girls always said they wanted to practise their English. But sometimes they also wanted to make you feel that you were in charge, in their country but safe in your own language.

There was another smiling pause.

‘Tak, spasibo,’ said the friend. (So, thank you.)

None of us moved. Then Masha said, ‘To where are you going?’

‘Home,’ I said. ‘Where are you going?’

‘We are only walking.’

‘Poguliaem,’ I said. (Let’s walk.)

And we did.

* * *

It was the middle of September. It’s the time of year Russians call ‘grandma’s summer’ – a bittersweet lick of velvety warmth that used to arrive after the peasant women had brought in their harvests, and now in Moscow means last-gasp outdoor drinking in the squares and around the Bulvar (the lovely old road around the Kremlin that has stretches of park between the lanes, with lawns, benches and statues of famous writers and forgotten revolutionaries). It’s the nicest time to visit, though I’m not certain we ever will. The stalls outside the Metro stations were laying out their fake-fur Chinese gloves for the coming winter, but there were still long lines of tourists waiting to file through Lenin’s freak-show tomb in Red Square. In the hot afternoons half the women in the city were still wearing almost nothing.

We came up the smooth narrow steps from the underground passages beneath the square, arriving outside the Armenian supermarket. We crossed the gridlocked lanes of traffic to the broad pavement in the middle of the Bulvar. There was only one cloud in the sky, plus a fluffy plume of smoke flying up from a factory or inner-city power plant, just visible against the early evening blue. It was beautiful. The air smelled of cheap petrol, grilled meat and lust.

The older one asked, in English, ‘What is your job in Moscow, if it is not secret?’

‘I am a lawyer,’ I said in Russian.

They spoke to each other very quickly, too fast and low for me to understand.

The younger one said, ‘For how much years you have been in Moscow?’

‘Four years,’ I said. ‘Nearly four years.’

‘Are you liking it?’ said the sunglasses girl. ‘Are you liking our Moscow?’

I said that I liked it very much, which is what I thought she’d want to hear. Most of them had a sort of automatic national pride, I’d discovered, even if all they wanted for themselves was to get the hell out of there and head for Los Angeles or the Côte d’Azur.

‘And what do you do?’ I asked her in Russian.

‘I am working in shop. For mobile phones.’

‘Where is your shop?’

‘Across river,’ she said. ‘Close to Tretyakov Gallery.’ After a few silent paces she added, ‘You speak beautiful Russian.’

She exaggerated. I spoke better Russian than most of the carpet-bagging bankers and mountebank consultants in the city – the pseudo-posh Englishmen, strong-toothed Americans and misleading Scandinavians the black-gold rush had brought to Moscow, who mostly managed to shuttle between their offices, gated apartments, expense-account brothels, upscale restaurants and the airport on twenty-odd words. I was on my way to being fluent, but my accent still gave me away halfway through my first syllable. Masha and Katya must have clocked me as a foreigner even before I opened my mouth. I suppose I was easy to spot. It was a Sunday, and I was on my way home from some awkward expat get-together in a lonely accountant’s flat. I was wearing new-ish jeans and suede boots, I remember, and a dark V-neck sweater with a Marks & Spencer’s shirt underneath. People didn’t dress like that in Moscow. Anybody with money went in for film-star shirts and Italian shoes, and everybody without money, which was most people, wore contraband army surplus, or cheap Belarussian boots and bleak trousers.

Masha, on the other hand, was authentically beautiful in English, even if her grammar was shaky. Some Russian women shoot up into a sort of over-elocutioned squeak when they speak English, but she had a voice that dropped down, almost to a growl, hungrily rolling her Rs. Her voice sounded like it had been through an all-night party. Or a war.

We were walking towards the beer tents that go up for the summer on the first warm day in May, when the whole city takes to the streets and anything can happen, and are folded up again in October when grandma’s summer is over.

‘Tell me, please,’ said the younger one. ‘My friend said me that in England you have two…’

She broke off to confer with her companion in Russian. I heard ‘hot’, ‘cold’, ‘water’.

‘What is it called,’ the older one said, ‘where water comes? In bathroom?’

‘Taps.’

‘Yes, taps,’ the younger one went on. ‘My friend said me that in England there is two taps. So hot water sometimes is burning her hand.’

‘Da, eta pravda,’ I said. (Yes, it’s true.) We were on a path in the middle of the Bulvar, near some seesaws and wobbly slides. A fat babushka was selling apples.

‘And is it true,’ she said, ‘that in London is always big fog?’

‘Nyet,’ I said. ‘A hundred years ago, yes, but not any more.’

She looked down at the ground. Masha, the sunglasses girl, smiled. When I think back on what I liked about her that first afternoon, apart from the long firm gazelle body, and the voice, and her eyes, it was the irony. She had an air that suggested she already knew how it would end, and almost wanted me to know that too. Maybe this is just how it seems to me now, but in a way I think she was already apologizing. I think that for her, people and their actions were somehow separate – as if you could just bury whatever you did and forget about it, as if your past belonged to someone else.

We reached the junction with my street. I had that drunk feeling that, before you, I always used to get in the company of premier-league women – half nervous, half rash, like I was acting, like I was living in someone else’s life and had to make the most of it while I could.

I gestured and said, ‘I live over here.’ Then I heard myself say, ‘Would you like to come up for some tea?’

You’ll think it sounds ridiculous, I know, me trying it on like that. But only a couple of years before, when foreigners were still considered exotic in Moscow and a lawyer was someone with a salary worth saying yes to, it might have worked. It had worked.

She said no.

‘But if it is interesting for you to call us,’ she said, ‘you may.’ She looked at her friend, who took a pen from the pocket above her left breast and wrote a phone number on the back of a trolley-bus ticket. She held it out to me, and I took it.

‘My name is Masha,’ she said. ‘This is Katya. She is my sister.’

‘I’m Nick,’ I said.

Katya leaned against me in her pink skirt and kissed me on the cheek. She smiled the other smile that they have, the Asiatic smile that means nothing. They walked away down the Bulvar, and I watched them for longer than I should have.

* * *

The Bulvar was full of boozers and sleepers and kissers. Gangs of teenagers clustered around squatting guitarists. It was still warm enough for all the windows of the restaurant on the corner of my street to be thrown open, ventilating the minigarch and mid-range hooker crowd that used to congregate there in the summer. I had to walk in the road to avoid the long, unimaginative sequence of black Mercedes and Hummers that had overrun the pavements around it. I turned into my street and walked along the side of the mustard-coloured church on the way to my flat.

I guess it might actually have been another day – maybe the image just seems to belong with the meeting on the Metro, so I remember them together – but in my mind it was the same evening that I first noticed the old Zhiguli. It was on my side of the street, sandwiched between two BMWs like a ghost of Russia past, or the answer to a simple odd-one-out puzzle. It was shaped like a child’s drawing of a car: a box on wheels, with another box on top in which the child might add a stick-man driver and his steering wheel, and silly round headlights on which, if he was feeling exuberant, the child would circle pupils to make them look like eyes. It was the sort of car that most of the men in Moscow had once spent half their lives waiting to buy, or so they were always telling you, saving and coveting and putting their names on waiting lists to get one, only to find – after the wall came down, they got America on TV and their better-connected compatriots got late-model imports – that even their dreams had been shabby. It was hard to be sure, but this one had probably once been a sort of rusty orange colour. It had mud and oil up its flanks, like a tank might after a battle – a dark crust that, if you were frank with yourself, you knew was how your insides looked after a few years in Moscow, and maybe your soul too.

The pavement on the way to my entrance had been left to dissolve into the road in the way that Russian pavements tend to. I walked past the churchyard and the Zhiguli to my building, punched in my code on the intercom and went inside.

I lived in one of the Moscow apartment blocks that were built as grand houses by doomed well-to-do merchants, just before the revolution. Like the city itself, it had been slapped about so much that it had come to look like several different buildings mashed together. An ugly lift had been fixed on to the outside and a fifth storey added to the top, but it had kept the original swirling ironwork of its staircase. Most of the front doors to the individual apartments were made of axe-resistant steel, but had been prettified with a sort of leather padding – a fashion that sometimes made it feel as though the whole of upscale Moscow was a low-security asylum. On the third floor the smell of cat litter and the screech of a nervous-breakdown Russian symphony emerged from my neighbour Oleg Nikolaevich’s place. On the fourth I turned the three locks on my padded door and went inside. I went into the kitchen, sat at my little bachelor’s table and took the trolley-bus ticket with Masha’s phone number on it out of my wallet.

In England, before you, I’d only ever had one thing with a woman that you might seriously call a relationship. You know about her, I think – Natalie. We met at college, though until someone’s drunken birthday party somewhere in Shoreditch we hadn’t thought of each other as contenders. I don’t think either of us had the energy to end it once it had started, and six or seven months later she moved into my old flat without me really agreeing or disagreeing. I wasn’t exactly relieved when she moved out again, saying that she needed to think and wanted me to think too, but I wasn’t devastated either. We’d lost touch even before I went to Moscow.

There had been a few Russian girls who’d seemed to be on their way to being proper girlfriends, but none of them lasted more than a summer. One became frustrated that I didn’t have and wouldn’t get the things she wanted and expected: a car, a driver to go with the car, one of those silly little dogs they drag around the designer shops in the cobbled alleys near the Kremlin. There was another one, Dasha I think her name was, who after the third time she stayed over began hiding things in the wardrobe and in the little cabinet above my bathroom sink: a scarf, an empty bottle of perfume, notes that said ‘I love you too’ in Russian. I asked Steve Walsh about it (you remember Steve, the lechy foreign correspondent – you came along when I met up with him in Soho once and didn’t like him). He told me that she was marking her territory, letting anybody else I brought home know that someone else had got there first. By that September you had to be careful who you hooked up with in Moscow – because of AIDS, but also because foreign men were going to clubs, meeting girls, leaving their drinks on the table when they went to take a piss, then waking up without their wallets in the backs of taxis they didn’t remember getting in to, or face down in puddles, or once or twice, probably when they got the dose wrong, not waking up at all.

I’d never found what people like my brother had, what my sister thought she had until she didn’t, what you and me are signing up for now: the contract, the settlement, the same body only and always – and, in return for all that, the back-up, the pet names and the head-stroking in the night when you feel like crying. I’d always thought I didn’t want it, not ever, to tell you the truth, that I could be one of the people who are happier without. I think maybe my parents had put me off the whole thing – starting out too young, banging out the kids without really thinking about it, forgetting whatever it was they liked about each other in the first place. By then it seemed to me my mum and dad were just sitting it out, two old dogs tied to the same kennel but too tired to fight any more. At home they watched television all the time so they didn’t have to talk to each other. I’m sure that, on the rare occasions they went out for a meal, they were one of those painful couples you sometimes see chewing together in silence.

But when I met Masha that day in September, somehow I thought she might be it, ‘the one’ I hadn’t been looking for. The wild chance of it seemed wonderful. Yes it was a physical thing, but not only. Maybe it was just the right time, but straight away I thought I could see her hair falling down the back of a towelling dressing gown as she made the coffee, picture her with her head resting asleep against me on a plane. If I was being blunt with you, I guess I might almost call it ‘falling in love’.

The smell of poplar trees crept in through the open windows of my kitchen, along with the sound of sirens and breaking glass. Some of me wanted her to be my future, and some other me wanted to do what I should have done, and throw the ticket with the phone number out of the kitchen window and into the pink and promising evening air.