0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Classica Libris

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

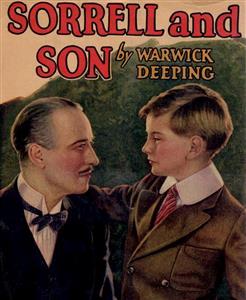

Set in England in the 1920’s, this story is about a father’s love, devotion and sacrifice for his beloved son. Captain Sorrell returns from the war to find his wife has left him with sole responsibility for their son Kit. Despite many deprivations, Sorrell strives to ensure his son will have the education and opportunities he never had. Will his efforts pay off? The book offers captivating insights into English society between the two World Wars.

Sorrell and Son became and remained a bestseller from its first publication in 1925 throughout the 1920s and 1930s and was made into a film that was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director in the 1st Academy Awards the following year.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Warwick Deeping

SORRELL AND SON

Copyright

First published in 1925

Copyright © 2020 Classica Libris

Chapter I

1

Sorrell was trying to fasten the straps of the little brown portmanteau, but since the portmanteau was old and also very full, he had to deal with it tenderly.

“Come and sit on this thing, Kit.”

The boy had been straddling a chair by the window, his interest divided between his father’s operations upon the portmanteau and a game of football that was being played in Lavender Street by a number of very dirty and very noisy small boys.

Christopher went and sat. He was a brown child of eleven, with a grave face and a sudden pleasant smile. His bent knees showed the shininess of his trousers.

“Have to be careful, you know,” said Sorrell.

The father’s dark head was close to the boy’s brown one. He too was shiny in a suit of blue serge. His long figure seemed to curve over the portmanteau with anxiously rounded shoulders and sallow and intent face. The child beside him made him look dusty and frail.

“Now, the other one, old chap. Can’t afford to be rough. Gently does it.”

He was a little out of breath, and he talked in short jerky sentences as he pulled carefully at the straps. A broken strap would be a disaster, for the clasp of the lock did not function, and this dread of a trivial disaster seemed to show in the carefulness of the man’s long and intelligent hands. They were cautious yet flurried. His breathing was audible in the room.

“That’s it.”

The words expressed relief. He was kneeling, and as he looked up towards the window and saw the strip of sky and the grimy cornice of grey slates of the house across the way, his poise suggested the crouch of a creature escaping from under some huge upraised foot. For the last three years, ever since his demobilization, life had been to Sorrell like some huge trampling beast, and he—a furtive thing down in the mud, panting, dodging, bewildered, resentful and afraid. Now he had succeeded in strapping that portmanteau. They were slipping away from under the shadow of the great beast. Something had turned up to help the man to save his last made-to-measure suit, his boy, and the remnant of his gentility.

Horrible word! He stroked his little black moustache and considered the portmanteau.

“Well—that’s that, son.”

He smiled faintly, and Kit’s more radiant smile broke out in response. To the boy the leaving of this beastly room in a beastly street was a glorious adventure, for they were going into the country.

“It will want a label, pater.”

“It will. ‘Sorrell and son, passengers, Staunton’!”

“How’s it going to the station?”

Sorrell rose, dusting the knees of his trousers. Each night he folded them carefully and put them under the mattress.

“I’ve arranged with Mr. Sawkins. He’ll take it early and leave it in the cloak-room.”

For Sorrell still kept his trousers creased, nor had he reached that state of mind when a man can contemplate with unaffected naturalness the handling of his own luggage. There were still things he did and did not do. He was a gentleman. True, society had come near to pushing him off the shelf of his class-consciousness into the welter of the casual and the unemployed, but though hanging by his hands, he had refused to drop. Hence Mr. Sawkins and Mr. Sawkins’ coster’s barrow, transport for the Sorrell baggage.

“What time is the train, pater?”

“Ten twenty.”

“And what time do we get to Staunton?”

“About three.”

“And where are we going to stay?”

“Oh—I shall get a room before fixing up with Mr. Verity. He may want us to live over—over the shop.”

There were times when Sorrell felt very self-conscious in the presence of the boy. The pose he had adopted before Christopher dated from the war, and it had survived various humiliations, hunger, shabbiness, and the melodramatic disappearance of Christopher’s mother. Sorrell turned and looked at himself in the mirror on the dressing table. He patted his dark hair. “Over—the shop.” Yes, the word had cost him an effort. “Captain Sorrell, M.C.” To Christopher he wished to remain Captain Sorrell, M.C. He felt moved to explain to the boy that Mr. Verity’s shop at Staunton was not an ordinary shop. Mr. Verity dealt in antiques; the business had flavour, perfume; it smelt of lavender and old rose-leaves and not of cheese or meat. Mr. Verity—too—appeared to be something of a character, an old bachelor, with a preference for a man of some breeding as a possible assistant. Also, Mr. Verity was a sentimentalist—a patriotic sentimentalist. He had been in correspondence with the Ex-Officers’ Association, and Stephen Sorrell had been offered the job.

He was going down to Staunton to discover whether he and Mr. Verity would harmonize.

Sorrell adjusted the wings of his bow tie and considered the problem of Christopher and Mr Verity’s shop. Should he be frank with the boy, or keep up the illusion of their separateness from the common world? He could say that he was going into business with Mr. Verity, and that in these days a shop—especially an antique shop—was quite a la mode.

Yells from the Street broke in upon his meditations. Someone had scored a goal, and someone else had refused to accept the validity of the goal.

“Damn those kids!” said the man.

He looked at his own boy.

“Pater.”

“Yes.”

“Shall I go to school at Staunton?”

“Of course. I expect there will be a Grammar School at Staunton. I shall arrange it when I have settled things with Mr. Verity.”

“Will it be a gentleman’s school, pater?”

“O, yes; we must see to that.”

There was a pause in the adventure, for on this last evening in London there was nothing left for them to do, and on warm evenings Lavender Street did not smell of herbs. Its smells were very various and unoriginal. It combined the domestic perfumes of boiled cabbage and fried fish with an aroma of horse-dung and rancid grease. It was a stuffy street. The clothes and bodies of most of its inhabitants exuded a perfume of stale sweat.

The boy had the imagined scent of the country in his nostrils.

“Let’s go out.”

“Where to?”

“Let’s go and look at the river.”

They went, becoming involved for a moment in a mob of small boys who were all yelling at once and trying to kick a piece of sacking stuffed with paper. Kit was pushed against his father, but reacting with sensitive sturdiness, upset one of the vociferous crew into the gutter where he forgot Kit’s shove in the business of eluding other feet.

Sorrell noticed that the boy was flushed. He was conscious of himself as of something other than those Lavender Street children. He did not want to be touched by them.

“We’ll be out of it tomorrow, son.”

“I’m glad,” said the boy.

Sorrell was thinking of Christopher’s schooling, and he was still thinking of it when they paused half-way across Hungerford Bridge and stood leaning on the iron rail. The boy had had to go to a Council school. He had hated it, and so had Sorrell, but for quite different reasons. With the man it had been a matter of resentful pride, but for the boy it had meant contact with common children, and Kit was not a common child. He had all the fastidious nauseas of a boy who has learnt to wash and to use a handkerchief, and not yell “Cheat” at everybody in the heat of a game.

Sorrell stood and dreamed, and yet remained aware of the kindling face of the boy who was watching the life of the river, a pleasure steamer going up-stream, a man straining at a sweep upon a barge, a police-boat heading for the grey arches of Waterloo Bridge. To Sorrell the scene was infinitely familiar yet bitterly strange. The soft grey atmosphere shot through with pale sunlight was the atmosphere of other evenings, and yet how different! His inward eyes looked through the eyes of the flesh. To him London had always seemed most beautiful here, a city of civic stateliness, mellow, floating upon the curve of the river. He had loved the blue black dusk and the lights, the dim dome of St. Paul’s like the half of a magic bubble, the old “Shot” towers, the battered redness of the Lion brewery, the opulence of the Cecil and the Savoy, the green of the trees in Charing Cross Gardens.

He remembered that he had dined and danced at the Savoy.

Spacious days! Khaki, and women who had seemed more than women on those life-thirsty nights when he had been home on leave. Odalisques!

Women! How through he was with women!

He remembered a night when he had taken his wife to the Savoy. Two years ago his wife had left him, and her leaving him had labelled him a shabby failure. She had had no need to utter the words. And all that scramble after the war, the disillusionment of it, the drying up of the fine and foolish enthusiasms, the women going to the rich fellows who had stayed at home, the bewilderment, the sense of bitter wrong, of blood poured out to be sucked up by the lips of a money-mad materialism.

He looked at the face of his boy.

“Yes, it’s just a scramble,” he thought, “but an organized scramble. The thing is to keep on your feet and fight, and not to get trampled on in the crush. Thank God I have got only one kid.”

Kit, head up, his cap in his hand, was smiling at something, the eager and vital boy with the clear eyes and fresh skin. To him life was beginning its adventure. He saw the river and the city in the splendour of their strength and their mystery. The Savoy and the Cecil were still palaces of the great and adventurous unknown, and Sorrell, full of the grim business of existence, felt a sudden deep tenderness towards the boy.

“I suppose it’s egotism,” he thought, “but I’ll try to give him a better chance in the scramble than I have had. After all we are more honest in our egotism—these days, the thing is not to love your neighbour, but to be able to make it unsafe for him to try and down you. Co-operation in bargaining, organized grab. But you have to bargain with some sort of weapon in your hand.”

Standing there beside his boy and watching the light and the life upon the river, Sorrell felt himself to be weaponless. What was he but a pair of hands, and a rather frail body in a shabby suit of clothes? He thought of his wounds, wounds of the flesh and of the spirit.

He met Kit’s smile.

“I say, pater, is there a river at Staunton?”

“A small one.”

He was realizing that the niche at Mr. Verity’s might also be a very small one, but at least it was a niche in the social precipice.

2

Sorrell and son arrived at Staunton about three in the afternoon. Amid the clatter of empty milk cans Sorrell addressed himself to the porter who was removing the brown portmanteau from the luggage van, but the porter either did not or would not trouble to hear him.

“Do you mind being careful with that? The straps—”

The porter swung the portmanteau out of the van and let it fall with a full flop upon the platform, and like Judas it burst asunder, and extruded a portion of its contents upon the asphalt.

Sorrell looked sad.

“You shouldn’t have done that, you know.”

It was a bad omen, and he bent down to recover a boot, a clothes brush and a tobacco tin, and to stuff the crumpled nakedness of an unwashed shirt back into the gaping interior. The porter, full of sudden compunction, bent down to help him.

“I’ll find you a bit of cord. The stitching of the straps must have been rotten.”

Christopher stood and looked on while Sorrell and the porter applied first aid to their piece of luggage. The incident had touched the boy; he had seen that look in his father’s eyes, and he felt—somehow—that it was not the portmanteau but his father who had gaped and betrayed a whole clutter of painful and shabby problems. Poor old pater! But his boy’s tenderness was touched with pride.

Sorrell was putting the porter’s contrition to other uses. Before reaching Staunton, he had counted the ready money that remained to him, and it amounted to thirteen shillings and five-pence.

“Do you know of any lodgings; clean, but not too dear?”

The porter was knotting a length of cord round the body of the portmanteau.

“Staying here? What sort of lodgings?”

“I am taking up a post in the town. A bed-sitting-room for me and the boy. I don’t mind how plain it is—”

“I’ve got an aunt,” said the porter, “who lets lodgings. There’s a room up at the top. Fletcher’s Lane. Not a hundred yards off.”

“Would she board us?”

“Feed you?”

“Yes.”

“She might. Look here—I’m going off duty in ten minutes or so. I’ll show you the way.”

“I’m very much obliged to you.”

Sorrell gave him the five pennies.

“Thank you, sir. I’ll pop this round for you on my shoulder.”

No. 7, Fletcher’s Lane, accepted the Sorrells and packed them away in a big attic-like room under the roof. It had a dormer window with a view of the cathedral towers and the trees of the Close, and between the cathedral and the dormer window of No. 7 every sort of roof and chimney ran in broken reds and greys and browns. The room was clean, and with a white coverlet on the bed, a square of linoleum in the centre of the floor, and a smaller piece in front of the yellow washstand. The chest of drawers had lost a leg and most of its paint, and when you opened a top drawer it was necessary to put a knee against one of the lower drawers to prevent the whole chest from toppling forward.

The landlady asked Sorrell if he would like tea, and he glanced at his wrist watch.

“I have to go out first. Would half-past five do?”

“Nicely. Will you take an egg to it?”

“Yes, an egg each, please. And could I have a little hot water?”

The hot water was forthcoming in a battered tin jug, and Sorrell washed himself, brushed his clothes and hair, wiped the dust from his boots, and glanced at himself in the little mirror. First impressions were important, and he wanted to make a good impression upon Mr. Verity. His blue suit was old and shiny, but it was well cut, and the trousers were creased.

“I’m just going round to see Mr. Verity. You might unpack, old chap.”

Christopher was leaning out of the window and inhaling the newness and the freshness of Staunton.

“Yes—I will, pater.”

“We’ll have some tea when I come back, and a stroll round. This is only a temporary roost.”

“It’s better than Lavender Street,” said the boy.

Mr. Verity’s shop was in the Market Square, and Sorrell, on turning out of Fletcher’s Lane found himself in Canon’s Row. A passing postman, questioned as to the whereabouts of the Market Square, jerked a thumb and said, “Straight on.” Sorrell did not hurry. He was pleasurably excited, and as he strolled up Canon’s Row, he saw the short, broad High Street opening out before him. It was all red and white and grey. The Angel Inn thrust out a floating golden figure. Higher up, a clock projected from the Market Hall with its stone pillars and Dutch roof, and its statue of William of Orange in a niche in the centre of the south wall. The Market Square spread itself, a great sunny space into which the more shadowy High Street flowed. It was surrounded by old houses that had been built when Anne and the Georges reigned. In the centre the market cross carried time back to the Tudors. A vine covered one little low house, and another was a smother of wistaria. There were queer bay windows, white porches, leaded hoods, and at the end the chequered Close threw a massive and emphatic shadow. Above and beyond, the towers caught the sunlight, rising from the green cushion of old limes and elms, and backed by brilliant white clouds in a sky of brilliant blue.

Sorrell paused outside the Angel Inn, for the old town pleased him. Not a bad spot to settle in, to listen to the bells, and to feel that life was less of a hectic scramble. And dabbling in old things, handling old china and glass and Sheffield plate, the creations of dead craftsmen who had not hurried. No doubt old Verity had absorbed the atmosphere of oak and mahogany, maple and walnut. He might have a richly brocaded soul.

Sorrell strolled on into the Market Square. He looked about him, and then crossed the cobbles and questioned a policeman who was on traffic duty.

“Mr. Verity’s shop?”

“Over there—near the gate.”

Sorrell was half-way across the Market Place when he realized that there was something queer about Mr. Verity’s shop. He saw it as a red house with a white cornice and white window sashes and painted in white letters on a black fascia-board “John Verity—Dealer in Antiques.” But the shop was shut, the windows were screened by black shutters.

Sorrell glanced at the other shops. No, it was not early closing day; the other shops were open.

He crossed the rest of the space more quickly, and sighting a black door beside the shop, with a brass bell handle in the white door-jamb, he pulled the bell. He was puzzled, aware of a sudden suspense, and when the door opened, he found himself staring at the face of a woman who had been weeping.

“Is Mr. Verity in?”

The woman’s eyelids flickered.

“Mr. Verity died this morning.”

Sorrell’s mouth hung open.

“What—!”

“Yes—sudden… It must have been his heart. He fell down the stairs—O—dear—”

She began to whimper, while Sorrell stood there with a blank face. He realized that the woman was closing the door.

He blurted something.

“I’ve just come down. I was to be—the assistant. It’s very—I’m sorry—”

“It was so sudden,” said the woman. “Of course—without him— nothing—you know. I’m sorry. Have you come far?”

“From London.”

“Dear, dear, and you will have to go all the way back—for nothing. It’s awkward, but there it is. If you’ll excuse me—now.”

She closed the door, and Sorrell stood staring at it.

3

Sorrell’s first feeling was one of bitter resentment against old Verity for dying in so sudden and inconvenient a fashion, but before he had recrossed the Market Square he had realized the absurdity of his anger. It died away, leaving him with a sense of emptiness at the pit of his stomach, and a chilly tremor quivering down his spine.

He was trembling. His knees were so weak under him that when he passed through the gateway of the Close, and saw a seat under a lime tree, he made towards it and sat down. He felt helpless, bewildered, for the disappointment—coming as the last of many such disappointments, seemed to have fallen on him with the cumulative weight of the whole series. He put a hand into a pocket for his pipe and pouch. His fingers moved jerkily, and when he lit a match his hand was so unsteady that he had difficulty in lighting his pipe.

The nausea of an intense discouragement was upon him, he felt tired, so tired that his impulse was to lie down and to admit defeat, and to allow himself to be trampled into the mud of forgetfulness. His senses were dulled, and the whole atmosphere of this quiet old town had changed. Half an hour ago he had been vividly aware of the blueness of the sky and of the tranquil white domed clouds floating above tower and tree, but now the objective world seemed vague and grey. His feeling of despair cast a shadow.

He thought of Christopher waiting in that upper room for his tea.

He shrank from the idea of facing the boy, of going back there with a hang-dog illusion dead in his eyes.

All the sordid and trivial realities of the business buzzed round him like flies. He had thirteen shillings in his pocket; he would owe the woman for food and a night’s lodging; there would be the cost of the tickets back to London; that damned portmanteau needed mending; and if they returned to London there was nowhere for them to go.

He realized the nearness of a panic mood.

He got up. “When you are in a blue funk, do something.” That was one of the human tags brought back from France. He remembered that he had won his M.C. by “Doing something” as a protest against the creeping paralysis of intense fear.

He walked back to Fletcher’s Lane, and climbing the stairs, paused for a moment outside the door of the room. He was trembling. He heard the woman moving somewhere below and leaning over the banisters he called to her.

“We are ready for tea, please.”

His own voice surprised him. It was resonant, and it had a quality of cheerfulness, and it seemed to express the upsurging within him of some subconscious element that was stronger than his conscious self. He opened the door and went in.

The boy was standing by the window. He had unpacked their belongings; a nightshirt and a pair of pyjamas lay on the bed; brushes, a razor, a comb, and three old pipes were arranged upon the dressing-table.

Father and son looked at each other.

“Well, my son, what about tea?”

Kit continued to look at his father; his eyes were very solemn.

“Mr. Verity’s dead,” said the father, “he died this morning. So— Staunton’s a wash-out. Well, what about tea?”

The boy’s face seemed to flush slightly. His lips moved, it was as though he was aware of something in his father, something fine and piteous, a courage, something that made him want to burst into tears.

“Sorry, pater.”

His lips quivered.

“We—we’ll have to make the best of it.”

And suddenly—with a kind of fierceness, Sorrell caught his son and kissed him.

4

Afterwards, they went out and sat in the cathedral and wandered about the Close under the shade of the elms and limes. The evening was very still, and the sunlight sifted through the trees and lay gently upon the mown grass. Swans cruised upon the moat surrounding the Bishop’s palace. There was the sheen of water, and the mellowness of old red walls seen through the dappled foliage of trees. The canons’ houses, sealed away in pleasant security, gave through their gateways glimpses of their gardens. Jackdaws circled about the towers, their cries dropping from above into the deeps of a green tranquillity.

A sunset filled the lacework of the leaves with red and gold, and the smooth and stately security of the Close caught moments of mystery. Sorrell and the boy were sitting on a seat above the water, with a slope of vivid grass going down to it, and a weeping willow trailing its branches in a stream of yellow light. It seemed to Sorrell that no one who lived near the shadowy splendour of these towers and trees could know what poverty was, or hunger, or the filthy dread that oozes like slime over a man’s soul. Life seemed so secure here, so incredibly secure.

He sat there, a shabby man beside a shabby child, and yet the shabbiness had fallen from him, the shabbiness of little, suburban make-believes. He had discovered a sudden and helpful frankness. He had undressed his soul before his boy.

They sat and talked.

“I’m not going to bother about the crease in my trousers my son. Keeping up appearances. I don’t care what the job is, but I am going to get it.”

The thing that astonished him was the way that the boy understood. How was it that he understood? It was almost womanish, a kind of tenderness, and yet manly, as he had known manliness at its best during the war.

“It was because of me—pater.”

“Captain Sorrell, M.C.”

“But you will still be Captain Sorrell, M.C., to me, daddy. If you swept the streets—”

“Honour bright?”

“Honour bright.”

Sorrell held Kit’s head against his shoulder.

“Seems to me, kid, that you and I have got to know each other as we never did before. Thanks to poor old Verity. I was so damned afraid that you were going to be ashamed of me—”

The boy smiled.

“Dear old pater—I’ll help.”

“Think of that poor old portmanteau! What its feelings must have been—when it burst open! But I have been burst open today, Kit. You have had a look at the inside of me. Yesterday—I was a sort of shabby gentleman. That’s finished.”

Christopher meditated some profound thought.

“I don’t mind—just bread and butter.”

“No jam?”

“No.”

“Well, somehow—I think it was worth it,” said Sorrell, “quite worth it. You and I know where we are.”

The sunset was dying behind them, and the dusk and the shadows of the great trees seemed to meet upon the water. The Sorrells left the seat and wandered away together, united by a sudden understanding of each other and by a sympathy that was frank and tender.

“I am always going to tell you things, Kit; no more make-believe.”

“And I’ll tell you things, too, pater,” said the boy, “everything.”

“No secrets?”

“No secrets.”

It was the beginning of the great comradeship between them, and for the first time for many months Sorrell felt a happiness that surprised him. The shock of the day’s disappointment had passed. The human relationship suddenly realized between his boy and himself swallowed up the sense of defeat. His courage returned. As they wandered in the dusk of the Close under the darkening trees, he felt Kit’s nearness, a nearness of spirit as well as of body.

“If I had not had the boy—” he thought.

Kit’s hand touched his sleeve.

“Look—”

They had turned into a stone flagged path that ran at the backs of the old houses on one side of the Market Square. Gravestones and brick tombs showed between them and the houses. A high yew hedge screened many of the lower windows, but Kit’s eyes were fixed upon a broad, arched window that was visible beyond the hedge. The window was brilliantly lit, and glowed with streaks of colour, orange, green, blue, cerise. A figure in black was moving amid the streaks of colour.

“What’s that?” the boy asked.

Sorrell smiled. They were looking across the old graves into the window of a Staunton modiste’s showroom, and it would seem that the modiste had received a consignment of silk “jumpers.” She was unpacking them and hanging them up on the stands in her showroom where they glowed brilliantly like jewels in a case.

“Clothes—Kit.”

“They look like bunches of flowers,” said the boy.

They passed on, and out by an iron gate into one of the Staunton streets, and so back to Fletcher’s Lane, where Sorrell sat and smoked while Christopher undressed and went to bed.

Sorrell sat there for a long while after the boy had fallen asleep.

“Yes—there’s my job,” he reflected.

Undressing very quietly so as not to wake his son, he slipped into the bed beside the boy and lay wondering how he would solve the problems of the morrow.

Chapter II

1

When Sorrell placed two rashers of bacon on Christopher’s plate, he found himself reflecting that he and his son were eating this meal on credit, and unless some sort of job was to be discovered in Staunton, he might have to visit the sign of the three golden balls.

At the end of the meal he lit his pipe and glanced down the list of the advertisements in a copy of the Staunton Argus. Someone was advertising for a chauffeur; a farmer needed a cowman, and a number of ladies were asking for cooks and housemaids, but Sorrell had to recognize his own limitation. He could not drive a car, or milk a cow, or cook a dinner. Indeed, when he came to consider the question there were very few things that he could do. Before the war he had sat at a desk and helped to conduct a business, but the business had died in 1917, and deny a business man his office chair and he becomes that most helpless of mortals—a gentleman of enforced leisure.

At the top right hand corner of the page Sorrell noticed a paragraph that might have some bearing on his case. It appeared that there was a private Employment Agency in Staunton, conducted by a Miss Hargreaves at No. 13, the High Street. Sorrell tore off the corner of the paper, slipped the notice into his waistcoat pocket, and passed the rest of the paper across the table to Christopher.

“I am going out.”

The boy understood.

“I’ll be here when you come back.”

No. 13 proved to be a stationer’s shop; one half of its window brilliant with the wrappers of cheap novels. Its doorway looked across the road into the arched entry of the “Angel” yard, and Miss Hargreaves, from the moment when she pulled up her blind in the morning till, she pulled it down at night, lived in the gilded presence of the inn’s angelic figurehead. Sorrell entered the shop. It was long and rambling and dark, and on dull days a light was needed in the far corner where the circulating library lived in a tall recess. There were no customers in the shop, and the young woman behind the counter, turning a pair of myopic eyes on Sorrell, moved instinctively towards where the daily papers were kept.

“Daily Mail?”

That was the sound she expected Sorrell to make, but he surprised her by uttering other words.

“I believe you run an employment agency.”

“Yes,” said the girl, “that’s so.”

She glanced in the direction of a kind of desk or cage at the back of the shop where a woman’s head was visible.

“You had better see Miss Hargreaves—there.”

As Sorrell approached the desk Miss Hargreaves raised her head, showing him the face of a woman of five and forty. She was thin and wiry, with brown eyes of a hungry hardness, and her nose marked out a little red triangle with its congested tip and network of minute blood-vessels.

“Good morning.”

He was a stranger, and to this woman all strange men were interesting, yet as Sorrell looked into her brown eyes, he felt himself growing inarticulate.

“I want to consult you—”

“You are wanting a servant?”

“No—the fact is—”

But at this moment they were interrupted by the rush of a vital presence into the shop, something highly scented and with the suggestion of the soft friction of silks. Its movements were large and easy and swift, and bringing with them a sense of disturbing and adventurous liveness. It was at Sorrell’s elbow, compelling him to glance over his shoulder. He saw the mass of tawny hair, the broad and handsome face, the red mouth, the blue of the eyes. There was something brutal in the face, a vivacity, a sensual energy. He felt as though a gust of wind had blown into the dark shop, and that this large, blonde creature was stifling his courage, overlaying it as though it were a feeble infant. He turned to the cage, only to find that Miss Hargreaves was all eyes for the newcomer.

The thin woman was smiling. Her face suggested some inward excitement.

“Morning—Flo—dear… How are you?”

“Do I look ill?”

There was some element of sympathy between these two women, contrasts though they were, but the lady of the tawny head was studying Sorrell. She stood aside, leaning easily against the wainscoting, her blue knitted coat vivid against the old brown wood.

“This gentleman—first. Mine’s not business.”

Sorrell wished her with the devil. He felt her eyes upon him, and had he followed the line of least resistance he would have bolted from the shop. To stand there and blurt out his shabby business while she embarrassed him and made him acutely self-conscious!

“Damn!” he thought, “haven’t I decided to plunge?”

Miss Hargreaves was fingering the leaves of a ledger and waiting upon his silence.

“You said you wished to engage—”

“I want a situation.”

“Oh—? For yourself? I’m sorry—but—only domestic service—you know.”

“Of course,” said Sorrell, stiff as a frightened cat, “that’s what I mean; a place as valet, or footman or something of that sort.”

He felt that the two women despised him, especially that big, blonde creature with her blueness and her hard world-wise eyes. Why couldn’t she clear out and leave him to the thin woman in the cage?

Miss Hargreaves pretended to glance through the entries in her ledger.

“I’m afraid I have nothing of that sort—nothing at all.”

“I see.”

“Why not try the Labour Exchange?”

“I might. Thank you. Sorry to have troubled you. Good morning.”

He turned abruptly, his back to the blonde woman and made for the doorway. He noticed how the worn boards of the floor squeaked under his feet, an uncomfortable sound caused by a discomfited man. He arrived at the doorway. A voice reached after him like a restraining hand.

“Hallo—one moment—”

Sorrell turned in the doorway, and saw the blonde woman sailing down the shop, and he stood aside to let her pass, thinking that his necessity was, no concern of hers, but she paused by a revolving stand of picture postcards, and taking one at random, gave Sorrell the full stare of her blue eyes.

“Serious?” she asked.

He looked at her rather blankly.

“I beg your pardon?”

Her smile puzzled him.

“Well—if you are—come across to the ‘Angel’ in a quarter of an hour. There’s a job—vacant.”

She passed out, almost brushing against him, and he watched her cross the road and enter the arched gateway of the Angel Inn. She turned to the left towards a doorway, but she did not look back, and he wondered why she had left him with a feeling of having been crushed against a wall. She had suggested immense strength, a brutal and laughing vitality.

Sorrell went back suddenly into the shop, and along its dark length to the woman in the cage.

“Excuse me—would you mind telling me—?”

She caught his meaning.

“That’s Mrs. Palfrey, she runs the ‘Angel.’”

“Oh. Have you any idea—”

Miss Hargreaves looked at him queerly.

“They want an odd man—for the luggage and the boots and things—”

He stared at her thin face.

“Well—why didn’t you—”

“Because I didn’t know,” she said tartly. “If it is any use to you—well—there it is.”

2

Sorrell stood on the footway and looked across at the Angel Inn.

The exterior of the building pleased him. It had the creamy whiteness of last year’s paint, and a well proportioned cornice that threw a definite shadow. The window sashes were painted maroon, and from the centre of the facade an old iron balcony projected like the poop of a ship. The gilded angel appeared to have floated from off this balcony, and there could be no doubt as to the rightness of the angel’s political opinions. She was a solid Tory angel who had pointed the way heavenwards to generations of Staunton crowds, carrying with her the eloquence of many triumphant Tory orators.

Sorrell’s glance travelled towards the arched entry, by which coaches and carriages had entered and left the inn in the old days. Above this entry a fine semi-circular window overhung the footwalk, two tall Ionic pillars, painted white, supporting it. Sorrell noticed that the curtains were of green taffeta. The window was fitted with window boxes, but the flowers in the boxes were dead.

He strolled up the street, across the Market Square and into the Close. He was undecided. He had glanced for a moment at the shuttered windows of Mr. Verity’s shop, only to realize how rapid had been the drop in his expectations. Odd man at a provincial pub! Assuredly he was landing with a bump at the very bottom of the social precipice.

He sat down on the seat and watched the swans, casual and stately creatures gliding as they pleased.

“Well—anyway,” he reflected, “if one starts at the bottom one has the satisfaction of feeling that one cannot drop any farther.”

He thought of Christopher.

“I said I would get a job. Any kind of job may be a ladder—to push the boy up. Or if he can climb up off my shoulders—”

He rose and walked back to the Angel Inn, and turning in at the arched entry, found a doorway on his left that led into a broad passage. He was to learn to know that passage very well, and to hate it and its slippery oil-cloth, and the stairs that went up from it into the darkness. A lounge enlarged itself on the right, the windows looking into the courtyard; and opening from the other side of the lounge were the office, the passage to the kitchen, the “Cubby Hole,” and the back entrance to the “Bar”!

Sorrell paused in the passage, with his back to a map of the surrounding country. Two or three visitors were seated in the lounge, smoking and reading the daily papers. A ruddy woman in a leather coat was turning over the pages of a Michelin guide. Sorrell noticed that the tables in the lounge had an uncared-for look. Tobacco ash and used matches littered the trays. There were the marks of glasses. The chair nearest to him needed the hands of an upholsterer. Moreover, the place had a distinctive and stuffy smell.

Sorrell approached the office window, and as he did so a man appeared at the doorway of the “Cubby Hole.” His suffused and injected eyes sighted Sorrell.

“Good morning, sir.”

“Good morning,” said Sorrell.

The man was in his shirt sleeves, unshaven, and his close-cropped head glistened white between his heavy shoulders; in fact his head seemed attached directly to his broad, short body without the interposition of a neck. His shortness made his bulk more evident, and even the effort of speaking appeared to render him short of breath, for Sorrell saw the labouring of the ballooned waistcoat. The man was not old, and yet he made Sorrell think of some poor, obese, mangy old dog with bleared eyes and panting flanks.

“What can I do for you, sir?”

His bluffness had a certain pathos. He appeared the master, a hearty, loud voiced creature, and he was nothing but an obedient sot.

“Mrs. Palfrey told me to call. It’s about—”

“About what—!”

“She is needing a man.”

“Oh—ah—that’s it.”

The brain behind the blotched face functioned very slowly, nor did the suffused blue eyes express any emotion. They did not change their look of solemn obfuscation.

The man moved to the door on which “The Cubby Hole” was painted in black letters. He opened it.

“Flo.”

“Hallo.”

“Someone to see you, a fellow after Tom’s place.”

“Show him in.”

As Sorrell responded to the gesture of a fat hand, he divined the fact that this poor, rotten shell of a man—the bruised and swollen fruit—was Florence Palfrey’s husband.

He closed the door and stood by it, holding his hat in his hand. It was a darkish room, with one window looking out upon a yard, and beneath the window ran a long sofa full of crimson coloured cushions. The woman was sitting on the sofa fiddling with some piece of needlework.

She did not tell Sorrell to sit down.

“Well, what’s your trouble been?” she asked abruptly.

He answered her with equal abruptness.

“Is that any business of yours?”

Her eyes seemed to take in his thinness, the black and whiteness of his rather solemn face with its little moustache and neatly brushed black hair. His quick reaction to her insolence did not displease her.

“Do you want this job?” she asked.

“That depends—”

“On your pride, my lad. Gentleman and ex-officer and all that!”

She pretended to fiddle with her needlework, and he looked down at her and met her occasional and baffling glances. He could not make her out. Her immense vitality, the brutal glow of her handsome strength made him feel like an inexperienced and shy boy. Why had she told him to come to her? Was it pity, good nature?

“I want work,” he said.

“Married?”

“No. But I have got a boy.”

She gave him a comprehending stare.

“What made you come to Staunton?”

“I had a berth offered me. At Verity’s. I came down yesterday. He was dead.”

She reflected for a moment; her head bent over her work.

“Rather a comedown for you.”

“That’s my affair.”

He had a feeling that she was amused at finding a man-creature in the corner of her cage.

“What about references, a character?”

“I could get you references from the Ex-Officers’ Association. My name is Sorrell, Captain Sorrell.”

“You will have to drop the ‘captain.’ Temporary, I suppose?”

“Yes. And what is the job?”

She dallied over revealing the details of the post he was to fill, as though it piqued her to discover at her leisure how much mauling the man-thing could bear.

“Of course—you are pretty raw. The thing is—you won’t be able to put on side. A man who cleans the boots in my house doesn’t put on side.”

“Point No. 1,” he said, “I clean the boots.”

“And carry up luggage.”

“Yes.”

“And keep an eye on the yard and the garage. By the way—know anything of billiards?”

“I play.”

“Then you know how to mark. Then—there is the ‘Bar.’ You will have to scrub that out every morning and give a hand sometimes with the drinks.”

“Right.”

She felt him growing stiffer with the swallowing of each detail. His pale face confronted her with an air of defiance. With each scratch of the claw he forced himself to a grimmer rigidity. He refused to wince.

“Anything else?”

“Oh—any odd job I may want done.”

“Yes.”

“And you will call me ‘madam.’”

She gave him a stare, and in it was a brutal curiosity. He was like a slave in the arena, down in the sand, and she was wondering whether he would cry for mercy.

“Very well, madam. And may I ask—what I get out of the job?”

“Thirty bob a week—and your keep.”

“Is that all?”

“Tips. Don’t forget the tips. If a man’s obliging—”

She gave an indescribable twitch of the shoulders.

“It’s a posh job—in the right place. You’ll live in—of course.”

Sorrell stood fingering his hat.

“And what about my boy?”

“I’m not engaging a boy. We don’t have children here. You can board him out somewhere, and he can go to school. How old?”

“Eleven.”

“Very well; it’s up to you, Sorrell. I can fill this place ten times over in half an hour.”

She saw the white teeth under the little black moustache, and she understood how he was feeling. He hated her. He could have struck her in the face, and his suppressed passion gave her the sort of emotion that she found pleasurable. She liked using her claws on men, driving them to various exasperations, and not for a long time had she had such a victim.

“I’ll take it,” he said. “When shall I start?”

She had turned on the sofa to place a finger on the push of an electric bell. Sorrell heard the distant “Burr” of it. She sat as though waiting for someone in order to keep him waiting.

“What did you say?”

Her manner was offhand.

“I asked you—madam—when I should start?”

“Right away. I’ll give you an hour to fix up that kid of yours.”

“Thank you,” he said, and opened the door to go.

But she called him back as her husband entered the room.

“I’ve taken this man on. He is going to fetch his things.”

Mr. Palfrey, stertorous and staring, was nothing but a fat figure of consent.

“Right, my dear.”

“That’s all, Sorrell. Be back in an hour.”

It took Sorrell five minutes to reach the upper room of the house in Fletcher’s Lane, and he found Christopher at the window looking out upon the world of Staunton’s roofs.

“I have got a job, Kit.”

The boy gave him that happy, radiant smile.

“I am glad, pater. What is it?”

Sorrell took one of the first steps towards the greater courage.

“I’m porter at the Angel Hotel.”

Chapter III

1

It took Stephen Sorrell the best part of a week to understand the “Atmosphere” of the Angel Inn at Staunton.

It was a little world in itself, a world dominated by that woman of blood and of brass, Florence Palfrey. The other humans were little, furtive figures, scuttling up and down passages and in and out of rooms. There were the two waitresses, the cook, the two chambermaids, and the apathetic young lady who helped in the bar. Poor, besotted John Palfrey, waddling about like a pathetic yet repulsive old dog, a creature of wind and of nothingness, was a voice and nothing more. He was perpetually fuddled. His hands trembled; his swollen waistcoat was never properly buttoned; even his gossipings in the “Cubby Hole” were like the blunderings of a brainless animal. Sometimes Sorrell found him in tears.

“What is it, sir?”

“I’ve lost—my slippers… It’s that damned pup—again.”

He gulped.

“Who cares—? I’m—I’m asking you? Not a blessed—soul—”

Sorrell would find his slippers for him, or his pipe, though he could not dry the poor creature’s silly tears. There were times when he himself was on the edge of tears, tears of rage or of exhaustion. He went to bed each night, worn out in mind and in body, so tired that he would lie awake and listen to the cathedral clock, or to the noises of his own body. The work was new to him; he was on the go from morning to night; the luggage pulled him to pieces. Moreover, the food was execrable, and those slovenly meals snatched anyhow and at any time in the slimy kitchen, turned sour in his tired stomach. Very often he was in pain.

But the thing that astonished him was the dirtiness of the place. From the street the Angel suggested cleanliness and comfort; the paint was fresh, the door-step white, but an observant eye might have noticed the dead flowers in the window boxes. Within, a cynical slovenliness prevailed. It was not safe to look under the carpets, or to reflect upon the blankets hidden by the treacherously clean sheets. There were places that smelt. As for the kitchen, and that awful dark and greasy hole where the dishes were washed, they made Sorrell wonder at the innocence of the people who ran their cars into the Angel yard and ate the Angel dinner and slept in the Angel beds.

The place had a sly filthiness. It was like a wench in silk stockings and lace whose ablutions were of the scantiest. Yet there was money in the “House.” Trade was good; Florence Palfrey never gave you the impression that she had to deny herself anything. She was brazen, voracious, insatiable, an animal with bowels full of fire. It was she who made out the bills, and in most of them there was some flagrant item against which the easy English visitor should have protested. In nine cases out of ten they remained mute and paid. Florence Palfrey knew her world. She bluffed. She chanced the protest, knowing that people would pay and go away and grumble and forget. She knew the world’s moral cowardice, its inertia.

Sorrell soon realized that the Angel as an hotel did not matter. The coffee-room, the commercial-room, the bedrooms were of no importance; what mattered was the bar.

Men came to booze.

In fact the “Cubby Hole” of the Angel Inn was a pivot, a fly-trap, a cave into which all sorts of male things crowded, and drank, and made silly noises and sillier laughter, and looked with lustful eyes at Florence Palfrey. At night the room would be full of them, and even in the daytime it was rare for the room beside the bar to be empty. This cavity had a secret, conspiratorial air. The men who sneaked into it dreamed of catching old Palfrey’s wife in a mood of consent, and of exciting moments among the red cushions.

The “Cubby Hole” filled Sorrell with nausea.

He began to know the names and the faces and the callings of the men who drifted into it. There was Romer—the managing clerk to Spens and Waterlove, a polite person with restless brown eyes and an unpleasant tongue. He had an amazing collection of stories. Biles, who owned the big butcher’s shop in High Street, would slip in with his red, greasy and furtive face, and would spill silly compliments from his coarse lips. Sadler the “Vet” went away each night stiffly drunk, moving like a figure on wires, his eyes fierce in his thin and debauched face. But there were dozens of them, farmers, tradesmen, commercial travellers, young bloods, all slinking in like dogs, drinking, and lounging and lusting.

“The fools—!”

Sorrell called them fools, and his scorn of them was part of his own pain. He had to mark for some of them in the billiard room, to listen to their dirty stories, to fetch them drinks. It was their amusement, and his torture, for often he was dropping with fatigue and boredom, and yearning for the fools to go to bed. And he would hear the laughter in the “Cubby Hole,” and the splurgings of these tradesmen who made love like bullocks.

“Floe—on thou shining river.”

That was Medlum’s jest, Medlum who kept the book-shop and sold prayer-books and Bibles and pretty-pretty art tourist guides, and who had a wife and seven children. He was a sandy man who looked as though he had been dipped in a bleaching vat, all save his mouth which was thin and red and lascivious.

They spent much money.

They would send poor old Palfrey up to bed, bemused, shuffling in his slippers, grabbing at the handrail. Often Sorrell would have to help John Palfrey up the stairs, listening to his pantings and to his fuddled confidences.

“She don’t care—not a damn. I’ve got water in me… I’m like a grape, Steve. What did the doctor call it? Ass—i-tis. Wish I were dead.”

He would pause at the top of the stairs, panting, and staring solemnly at Sorrell.

“You mark my words… A coffin—in six months I’m asking you… Who cares—?”

He would weep.

“You’re a good chap—Steve. Don’t know why. God—I feel sick.”

There were other things that Sorrell began to understand. Women came to the “Cubby Hole”; Miss Hargreaves from across the way, red nosed, excited, ready with thin, hard giggles; the lady who kept the fruit shop and who looked like an over-ripe plum, and who was always protesting that she could not bear to be tickled. “I’ll scream.”

These earthly souls soon ceased to puzzle him, but the woman of brass remained an enigma. She bullied these people, even when she treated them with brutal good-humour. She knew exactly how to handle each fool-man, and how to repulse some flushed face that was breathing too near to hers. There were times when Sorrell felt that she despised the whole crowd as much as he did.

And since a man must wonder, he went in pursuit of her motives. Did her huge vitality suck something from her herd of swine? Was it money? Did it cause poor Palfrey to disobey his doctor’s orders and to shuffle nearer to the inevitable coffin?

She was shrewd, like a strong and cunning animal. She never lost her dignity or allowed the amorous clowns to take liberties.

“I have seen something like her before,” he thought. “Where—?”

One wet night he remembered. The den was full of her Circe troop, and Sorrell, going in with a tray of glasses, saw her sitting on the sofa and looking over the heads of her adorers. Yes, he remembered. He had seen a lioness at the London Zoo, couched, and looking just like that, savagely and superbly indifferent. He could remember the way the tawny beast’s eyes had looked over the heads of the humans fidgeting and chattering outside the railings, those tame people, those monkeys. The lioness, couched up above, eyes fixed upon some distance of her own, had ignored them.

But she met Sorrell’s eyes, and a sudden glitter came into them.

He was closing and locking the hotel door when he heard her calling him.

“Stephen!”

He went to the door of the den. She was sitting on the sofa, yawning, and with the naturalness of a fine animal.

“What damned fools!”

She looked at him and picked up a cigarette from the table.

“I want a match.”

He produced a box, and striking a match, held it for her to light her cigarette. She blew smoke. Her eyes lifted suddenly, and he saw the big black pupils and the vivid blue of each iris.

“You look fagged.”

“It’s the end of the day.”

“You ought to get off more. You work too hard.”

Sorrell’s eyes dropped.

“If I could get out for an hour—after tea. There’s my boy; I don’t see much of him—”

Instantly he was aware of the fact that he had offended her.

“O—your boy! What’s he doing?”

“Going to school.”

“The Council School?”

“Well, it’s that—or—”

“A summons. All right—clear out for an hour each day. Have you locked up?”

“Yes, madam.”

He had a glimpse of her profile as he passed the door on his way to the stairs. She was smoking and looking at and through the wall opposite her. The corner of her mouth was drawn down and she was frowning.

2

Sorrell had particular moments in the day when life was worth living. One of the moments was when he got to his attic at night and counted up the day’s tips and entered the amount in a little black note-book; the other moment of happiness came to him with a daily glimpse of the clean, frank face of his boy.

Kit would come to the arched entry, and Sorrell would meet him there, and Kit would see his father in the old, familiar blue serge suit grown more shiny and less neatly creased about the trousers. There were times when Sorrell wore an apron, but he contrived to appear before Christopher minus the apron. His pride allowed itself this little satisfaction.

They would stand together for five minutes beside one of the white Ionic pillars supporting the bow window of the dining-room, the boy looking up into his father’s face. He was an observant child, and his love for Sorrell had undergone a transfiguration. Christopher noticed changes in his father’s face; it looked more waxy; there were little wrinkles as of a troublesome knot of effort lying between the eyebrows. Sorrell was thinner; he stooped more.

But Sorrell’s eyes smiled.

“How’s she feeding you, son?”

Christopher had no complaint to make of the food that Mrs. Barter gave him at No.13 Fletcher’s Lane. She was a good woman.

“She’s been mending my shirts, pater.”

“Ha,” said Sorrell, “Has she!” and glanced at the boy’s suit. Yes, that fresh face contrasted with the shabby clothes.

“Time I took you to the tailor, my lad. I think I can manage it next week.”

Christopher could not analyse all that lay behind his father’s eyes, but he felt the warmth of the love in them. He noticed that his father’s eyes had a filminess, a veiled and secret delight, a moment of deep dreaming. They were the eyes of a man who was thirsty, and to whom the boy brought pure, clean water. Christopher refreshed him. His candid eyes and the brown warmth of his clear skin were unblemished fruit after the rottenness of those squashed and purple souls, those men who made Sorrell think of faces trodden on by an ever-passing crowd of sordid and unclean thoughts. His boy had youth, a future, possibilities; he was the sun in the east.

And poor Palfrey!

“My God!” Sorrell thought, “One must hold on to something, even if it is nothing but a clean shirt and a piece of soap.”

Christopher never asked questions, awkward and embarrassing questions. He accepted his father’s job, and he understood the significance of it far more subtly than Sorrell knew. It reacted on the boy and deepened his sensitive seriousness.

At school he was very careful of his clothes. He did not say much about the school. It was all right. Better than London. What did he do in the evenings? O—went for walks, mostly. There were woods outside the town, and the river.

Those few minutes were very precious to Sorrell, but they tantalized him. His boy was so apart from him all through the day, and whenever they met, he would look eagerly at that frankly radiant face for the shadow of any possible blemish.

He felt so responsible, greedily responsible. The boy’s clean eyes made the life at the Angel possible.

On one occasion when he had walked a little way along the footpath with Christopher, he became aware of a face at a window. The woman was watching them. He caught her bold, considering eyes fixed on the boy.

He went back rather hurriedly into the passage and met her there.

“That your kid, Stephen?”

“Yes, madam.”

“He’s not a bit like you. The mother’s dead, I suppose?”

“I divorced her,” said Sorrell, pale and stiff about the lips.

Usually, it was about eleven at night when he went slowly up the narrow staircase to the top landing where the staff slept. He carried a candle. Sometimes he would hear giggling and chattering in one of the girl’s rooms, but he always went straight to his own, shut the door, put the candlestick on the chair, sat down on the bed and turned out his pockets. At this hour he did his precious calculations. His little black note-book was a model of neatness, with credit and debit entries.

July 7. Wages £1 10 0 Christopher—Board £1 0 0

“ 7. ” Tips 4 6 Tobacco 2 0

“ 8. ” 3 0 Tooth brush 1 0

“ 9. ” 0 Christopher—Boots 1 0 0

“ 10. ” 7 0

“ 11. ” 5 6

“ 12. ” 1 0

“ 13. ” 9 0

He found that his tips averaged about twenty-five shillings a week. He paid Mrs. Barter a pound a week for Christopher’s keep. He spent a few odd shillings on himself. He was contriving to save about a pound a week. £52 a year? If his health held out?

Already he had a plan for his boy, an objective that showed like a distant light through the fog of the days’ confusion.

“It’s my business to do my job thoroughly,” he thought, “In order to get Kit a better one. I’ll save every damned penny.”

Life, the life that should have appealed to the cruder of his own appetites, had ceased to attract him, and all his energy appeared to concentrate itself and to flow in one particular channel. He developed a peculiar passion for thoroughness, even though he might curse the inanimate things upon which he had to exercise this thoroughness. Queerly enough, much of his thinking and his philosophizing were done while he was cleaning the various pairs of boots and shoes left outside the bedroom doors. He did not mind this job—though scrubbing the bar floor made his gorge rise. It was like cleaning out a pen where unclean animals had left their ordure. But boots—! Boots had character. He got into the way of estimating the owners of the boots by their footgear. He had a preference for neat brown shoes, gentlemen’s shoes, and his favourites came in for more polish. Young women’s shoes—were they ever so chic—gave him no thrills. The boots he detested were the boots worn by a particular type of middle-aged commercial traveller, men who trod heavily and whose waistcoats bulged. He never put a hand inside one of these “Swine’s trotters” as he called them.

But with a free hour each day snatched from the Lioness’s rather jealous paws, Sorrell began to see more of Christopher. He took his hour off from eight till nine, for he had found that too many motorists arrived after tea and he was not there to handle the luggage and to carry it up from the garage. He wished to be in evidence because of the subsequent tips. But in these long summer evenings he and Christopher wandered together; sometimes they chose the Close, on other evenings they wandered out a little way into the country; if it was wet Mrs. Barter let them sit in her parlour. She was kind to Sorrell she offered to do his mending for him.

Christopher loved trees. There was a particular elm in the Close, a green giant with a ring seat round its bole, under which the boy liked to sit. Nor was Sorrell sorry to sit. It conserved boot leather and rested his tired feet. Kit had noticed on their short country rambles that his father walked as though his feet hurt him. He had noticed—too—that one of the boots was patched.

“Your turn next—pater?”

“What for, son?”

“Boots,” said the boy.

He had fatherly moments towards Sorrell. He too had his plans, vague ambitions, and impulse that pushed him towards some magnificent job in the doing of which he would earn much money. He had sensed the effort in his father’s life; he dreamed of taking his share of the effort.

“I can start work at fifteen, pater.”

Sorrell was astonished.

“I hope not,” he said, and glancing from the boy’s face to the spreading branches of the elm he saw life and its effort symbolized.

“Most people grow like cabbages. Look at this tree. How many years—eh? O—it was not in a hurry. We—are not going to be in a hurry.”

The boy’s eyes were questioning.

“Not as long as that—With you—sweating—and doing everything—”

“It’s my job, Kit.”

He looked mysterious.

“I’ve got plans. The thing is—Well, you don’t know yet—what you will want to do—I mean. No blind alleys, or office stools.”

“You mean—dad—what I would like to be?”

“That’s it.”

“Seems—one’s got to earn money.”

“Wait a bit. There’s something better: how you earn it. The real job matters more than the money.”

“Yes,” said Christopher very solemnly, “the sort of thing you love doing. Well—I suppose I shall find out.”

Chapter IV

1

An incident that occurred about five weeks after Sorrell’s arrival at the Angel startled him into a sudden aliveness towards the drift of other people’s temperamental whimsies.