4,56 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

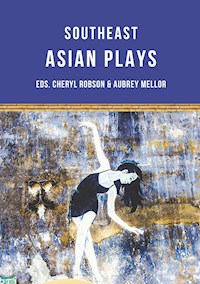

The first ever comprehensive collection of plays in English from Southeast Asia. Features work by eight playwrights from seven countries in Southeast Asia, a region which is experiencing profound change: Singapore, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia and Cambodia. Southeast Asian Plays explores the rich variety of dramatic work that is only beginning to be translated into English.

Theatre scripts are merely blueprints for productions, especially in this region. As elsewhere, second productions and revivals are rare, so publication is key to allowing play texts to find a wider international readership.

Topics include the global financial crisis, sex workers, traditional v modern values, the role of faith in society, corruption in high places and journalistic ethics. The plays have been selected for performance.

Plays:

The Plunge by Jean Tay (Singapore) about the efects of a financial crisis

An Evening At the Opera by Floy Quintos (Philippines) about a dictator and his wife

Night of the Minotaur by Tew Bunnag (Thailand) about a man misused as a monster

Tarap Man by Ann Lee (Malaysia) about a man wrongly imprisoned under the justice system

Dark Race by Dang Chuong (Vietnam) about corruption in high places

Frangipani by Chhon Sina (Cambodia) about the sex trade in Cambodia

Piknic by Joned Suryatmoko (Indonesia) about the need to get rich quick in Bali

Nadirah by Alfian Saat (Singapore) about the conflict between faith and morality

"The editors have done an excellent job of opening up our chances of reading and learning about plays from all over Southeast Asia. ...editorial choices are significant for opening up spaces to voices which are otherwise heard less often. All in all the plays are interesting for the ways in which they grapple with key concerns in their respective societies." --The Asiatic

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 466

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

AUBREY MELLOR

Theatre Director, Dramaturge and Teacher with expertise in new work and classics – especially Chekhov, Shakespeare and Brecht. Formerly Dean of Performing Arts at Lasalle and Director of the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA), associated with arts training colleges across Australasia, Mellor has directed a range of genres from opera, dance and film. He is well-known as an acting teacher to a generation of acclaimed Australian actors, and renowned for translations and productions of the classics and for development of new work.

Brought up in Variety and Circus, Mellor trained as a dancer, visual artist and musician and graduated from NIDA Production Course. In 1972 he was awarded a Churchill Fellowship, the first Australian to study Asian theatre, from Japan to India. Mellor’s leadership credits include: Artistic Director of the Jane Street Theatre (Sydney); Co-Artistic Director of Nimrod Theatre Company (Sydney); Deputy Director of NIDA; Artistic Director of the (Royal) Queensland Theatre Company; and Artistic Director of Playbox-Malthouse in Melbourne.

He was awarded the Order of Australia Medal in 1992 for services to the arts; Australian Writers’ Guild’s Dorothy Crawford Award for services to Playwriting; and the International Theatre Institute’s Uchimura Prize for best production, Tokyo International Festival. He is a visiting professor to theatre schools in Japan, China, Mongolia, India, Indonesia and Vietnam.

CHERYL ROBSON

Writer, editor and filmmaker, Cheryl was born in Australia and has recently been creating literary projects in Singapore. She worked at the BBC in London for several years before setting up a theatre company producing and developing women’s plays. She also created a publishing company where she has published over 150 international writers and won numerous awards. As a writer, she has won the Croydon Warehouse International Playwriting Competition and has had several stage plays produced.

Her film Rock ‘n’ Roll Island, has been selected for several film festivals in the UK and USA, won a Gold Remi at Houston Worldfest and was nominated Best Documentary Short at Raindance London.

www.cherylrobson.net.

First published in the UK in 2016 by Aurora Metro Publications Ltd

67 Grove Avenue, Twickenham, TW1 4HX

www.aurorametro.com | [email protected]

Plunge copyright © 2009 Jean Tay

An Evening at the Opera copyright © 2011 Floy Quintos

The Night of the Minotaur copyright © 2016 Tew Bunnag

Tarap Man copyright © 2016 Ann Lee

Dark Race copyright © 2016 Nguyễn Đăng Chương

Frangipani copyright © 2016 Chhon Sina

Frangipani translation copyright © 2016 Suon Bunrith

Piknik copyright © 2011 Joned Suryatmoko

Piknik translation copyright © 2016 Barbara Hatley

Nadirah copyright © 2009 Alfian Sa’at

Production: Gabriella Palermo and Simon Smith

With thanks to: Neil Gregory, Ivett Saliba and Sumedha Mane.

All rights are strictly reserved. For rights enquiries including performing rights please contact the publisher: [email protected]

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

In accordance with Section 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, the authors and translators assert their moral right to be identified with the above works.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

ISBN: 978-1-906582-86-9 (print)

ISBN: 978-1-910798-88-1 (ebook)

SOUTHEAST

ASIAN PLAYS

EDS. CHERYL ROBSON & AUBREY MELLOR

With thanks to all who helped with this book including:

Ricardo G. Abad, Layne Alera, Joachim Emilio Antonio, Joem Antonio, Tuyen Boal, Stephanie Charamnac, Chong Tze Chien, Jose Christomo, Giles Croft, Joe Dalisay, LeQuy Duong, Kelly Falconer, Arthur Foo, Anna Furse, Karlo Antonio Galay-David, Barbara Hatley, Ivan Heng, Tan Tarn How, Shaza Ishak, Koes Juliadi, Irfan Kasban, Jo Kukathas, Ann Lee, Leow Puay Tin, Melissa Lim, Suchen Christine Lim, Robin Loon, Helen Mangham, Faiza Marzoeki, Pawit Mahasarinand, Glen Sevilla Mas, Kumiko Mendl, Raymond Miranda, Amir Muhammad, Helen Musa, BaoChan Nguyen, Yang-Mai Ooi, Ridzwan Othman, Andrea Pasion-Flores, William Phuan, Ruth Pongstaphone, Venka Purushothaman, Charlene Delia Jeyamani Rajendran, Nerida Rand, Kathy Rowland, Frances Rudgard, Hj. Yudiaryani, Haresh Sharma, Arun Subramanian, Huzir Sulaiman, Alvin Tan, Mark Teh, Pham Tir Thanh, Maung Maung Thein, Nyein Way, Sokhorn Yon and Ovidia Yu.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Aubrey Mellor

PLUNGE

Jean Tay

AN EVENING AT THE OPERA

Floy Quintos

THE NIGHT OF THE MINOTAUR

Tew Bunnag

TARAP MAN

Ann Lee

DARK RACE

Nguyễn Đăng Chương

FRANGIPANI

Chhon Sinatranslated by Suon Bunrith

PIKNIK

Joned Suryatmokotranslated by Barbara Hatley

NADIRAH

Alfian Sa’at

INTRODUCTION

This volume is but a taste of the rich variety of performance work that in many cases is only beginning to be written down. Though now in English, there is little in common in these eight plays from seven very different nations in a region connected mainly by geography. Until the founding of ASEAN, in 1967, Southeast Asia (SEA) was known to the world as the East Indies. Covering 11 nations and 626 million inhabitants, over more than 4.4 million square kilometres, the southeast of the continent plunges into the sea, diversifying into many thousands of islands and languages as it reaches into the Pacific. One of the largest and fastest-growing economies of the world, with a combined annual turnover of 2.8 trillion US dollars, it contains arguably the richest variety of arts, customs, cuisines and landscapes – and distinctively defined peoples. However, this part of the world is under-represented, especially in theatre and dramatic writing, and its vivid diversity deserves to be known beyond its splendid beaches and tourist spots. In collecting a first volume of Southeast Asian playscripts we prioritised material that other countries (including SEA) might be interested in performing, with an aim to introduce not only the writers but also the cultures that produced them.

Theatre across Asia remains close to its oral traditions and to its prime expression in dance and music. Every country has its impressive, skilful, colourful performance traditions, with the wealth of styles and forms having even more numerous regional variations. It is well known that Brecht was influenced by the arts of Chinese Xiqu (erroneously known as ‘opera’) but few know the influence of Balinese performance upon Artaud and Grotowsky.

Asia’s love of performance remains tangible and can be seen at village level as well as in its large arts centres; so it is not surprising that with its economic developments Asia is drawing performance influences from anywhere that excites. In some cases this has left regional variants of traditional performance styles endangered, but in others, fascinating experiments are drawing from their heritage and mixing concepts with the best from Europe and the Americas.

Southeast Asia is also a region at considerable peace with – and interested in – its neighbours: companies commonly mix performers of several countries on their stages, and collaborations, often long-term, result in unique theatre that shows considerable leadership – not only in theatrical innovation but also in cultural, racial and religious tolerance and respect. English-language theatre is common in Singapore, but so are plays in Chinese and modern Japanese plays are often seen in many of these countries. However, in Southeast Asia it is still easier to buy a British playscript than one by a Thai or Vietnamese. More and more, English is the language used when Asian companies and artists communicate, and though interest in these works will be global, their first foreign productions are most likely to be seen in this region.

Fascinating as traditional Asian theatre remains, its roots in vastly different worlds mean that traditional performance can seem very foreign, often alienating. I have experienced the touring of both traditional and contemporary works and emphatically believe that it is the contemporary that brings us together: within spoken drama we more easily relate to characters and their problems, however different their living conditions might be. The contemporary plays in this volume radically depart from SEA traditional theatre and several reveal their authors’ cosmopolitan influences and their globalised and highly networked lives. All plays are internationally accessible, their language and form familiar, and the acting style generally naturalistic. This collection does not include any musicals or music theatre, though both are extremely popular, and it does not cover the most experimental work of writers and theatre-makers consciously exploring intercultural and interdisciplinary combinations. A prime example is the region’s best-known international director, Ong Keng Sen, who pioneered extraordinary combinations of styles, forms and genres and through Theatrework’s ‘Flying Circus Project’ develops cross-nation performances with a range of companies such as Myanmar’s Theatre of the Disturbed. We have, however, selected plays with direct appeal to Western audiences and are confident they will find directors and actors to inhabit their characters.

Storytellers and leading performers always had the respect of their community, but most countries in this region still retain a collaborative approach to theatre-making and new work can often be yet another re-telling of a section of a larger work, as Southeast Asia is home to many huge oral epics that continue to inspire – The Ramayana being common to many. Along with Western-style theatre buildings, Western forms of drama arrived with the colonisers; but wider assimilation is post-colonial, and quick to explore local and contemporary themes. Modern drama was in many cases crucial in the struggle for independence, and is still playing a role in nation-building. Content, especially topicality, rarely the focus in traditional arts, is a prime feature of SEA’s contemporary dramatic literature, as revealed in this collection.

Alfian Sa’at’s Nadirah is highly topical as it addresses the theme of mixed marriages; in asking if mother and daughter can worship different gods, Sa’at welcomes the new developments in Singapore’s multi-racial and multi-faithed society. In Plunge, ex-economist Jean Tay shines satirical light on the Asian Economic Crisis, and with considerable boldness and innovation reveals Singapore’s sophistication on the global market (she has since followed with a related play called Boom). Malaysian writer, Ann Lee, brings a female journalist face to face with a gruesome murderer, only to question if he has been falsely imprisoned since he was a boy. Tarap Man articulates the region’s growing interest in truth and justice.

Refreshing evidence of liberal thinking comes from Vietnam’s Đăng Chương, with Dark Race, a satirical look at personal integrity in business and political leaders; and Floy Quintos considers the misrule that has held many Asian countries back in An Evening At The Opera. This is a behind-the-scenes portrayal of elite and sinister power, echoing a Philippines that is hopefully gone. In Tew Bunnag’s Night of the Minotaur, from Thailand, power is confined to a cave and treated like a beast. The powerless are given voice in the plays from Indonesia and Cambodia, respectively in Joned Suryatmoko’s Piknik and Chhon Sina’s Frangipani, reminding us that poverty can easily lead to abuse and exploitation.

Publication is not a necessary goal in the performing arts, and theatre scripts are merely blueprints for productions, especially in this region. As elsewhere, second productions and revivals are rare, so publication becomes important to preserving some of this ephemeral art form and to allowing play texts to find a wider international readership. Though some of these works were written and performed in English, a play’s origins are of course defined by language, e.g. a Vietnamese play is written in Vietnamese etc. Consequently the huge majority of new dramatic literature in this flourishing region remains unknown outside of language borders; even within countries plays are not readily circulated, as they are not commonly published in their original (often local) language, and are further neglected in translation. The development of skilled literary translators in the region is happening slowly, but the focus is primarily on poetry and fiction.

Japan is the only country I know where its government spends considerably on translations of plays into English; but, sadly, despite efforts of collections such as this, an English-speaking repertoire still doesn’t include either classic or contemporary Asian plays. The authors in this collection are bi- or multi-lingual, and most works are newly translated, with some playwrights having their first play published. We have not included bi-lingual plays, but in Malaysia and Singapore three languages in the one play are quite common.

Unlike India, China and Japan with their vast recorded heritage of dramatic literature, the smaller countries have only recently been able to focus on the importance of contemporary literature. Poetry often came first, though usually by the internationally educated, and it often flourished, as it could always evade censorship. Novels followed, at first unusual but soon enjoyed and acclaimed, even internationally, such as Tan Twan Eng’s The Garden of Evening Mists and Suchen Christine Lim’s The River’s Song, and many are now on schools’ study lists. Reading them will give excellent context for the plays.

With some exceptions, playwriting with an individual voice is relatively new, despite some deceased giants in the past, such as Indonesia’s W.S. Rendra and Singapore’s Kuo Pao Kun, whose work is published and internationally performed. New writing has long been supported by visionary directors in every country, such as Krishen Jit, Rolando Tinio, Alvin Tan; and dedicated centres, like Jo Kukathas’ pioneering Instant Cafe in Kuala Lumpur, are now being established – for example, Manila’s Sipat Lawin and Singapore’s Centre 42. Script collaboration is common, and often the actors make considerable contributions, especially in Indonesia. The dramaturge role is still new, though more common in dance works and company-produced works rather than as personal support for an individual playwright, and feedback to writers must be sensitively handled, as not only is ‘face’ involved, but writers are not used to having an advisor or editor, and though often they work with a trusted director, such is usually towards the end of the writing process, not during.

Traditional theatre always had a place for satirical inserts and social comment, but entirely new playscripts, especially when written to argue new ideas, were first seen as a Western concept. The proscenium arch was innovative, and European touring productions not uncommon, Shakespeare impacted widely, though mostly in India, whilst foreign residents enjoyed dressing up to dabble in amateur theatre. However, following independence, the reaction against expatriates’ theatre saw an explosion of new forms, embracing new ideas from almost anywhere, including influences such as Brecht, the Absurdists and The Living Theatre and using them to tell local stories of relevance. Dance and physical storytelling have remained strong, and in Indonesia, Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam, governments have deliberately prioritized dance and crafts as the most endangered parts of their culture and have had remarkable success in rescuing and revitalising many regional variants. But ‘The Word’ is still considered more potent than the abstractions of music and dance, and censorship can still be found. However, in most governments in the region, there is an enlightened interest in what an artist can bring to a nation.

Some beautiful old theatre buildings have survived from colonial days – see the two splendid opera houses in Vietnam; but, until independence, these never belonged to the people, whose participation in performance was far less formal. But arts centres are now a sign of prestige and modernity; and though glass and concrete structures can be daunting for ordinary people, even in the West, they house a number of spaces that support exhibitions, performances and, importantly, meeting places for both community and creatives. Further signs of healthy arts scenes are found in the converted shopfronts and warehouses used as homes for small theatre groups and arts groups.

People in Southeast Asia fully embraced new technology several decades ago, and portable entertainment, both local and global, is greatly loved; as in the West, digital technology and social media is drawing audiences away, but new technology grows more evident in local performance. Unusual and site-specific locations – as well as audience involvement – often complement this, as practitioners work to meet every challenge. The film industries of most nations represented in this collection are more influential than their theatre, and in some cases writers manage to work in both, but the low status of playwriting is maintained by poor copyright laws, ensuring that even if a second production is achieved the author will often not receive any percentage of box office receipts from it. Though Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines are ahead in their respect for playwriting and play publishing, elsewhere plays are produced through little more than a shared passion in a small group of people.

Though companies are numerous, large theatre companies are rare and any commissioning of plays needs government support or other patronage. Fortunately, universities have always had literary programs and in most countries have set up creative writing courses, drama departments, and drama schools, where international plays are studied and where new plays are supported and often produced – for example, in Thailand, Chulalongkorn University’s most appropriate telling of the real Anna Leonowens story (Anna of The King and I fabrication – Chulalongkorn being then the Crown Prince whom she taught).

Drama festivals are plentiful, along with Writers’ Festivals, such as in Ubud where it includes playreadings, and many were started by individuals such as Joned Suryatmoko, Director of the Indonesian Dramatic Reading Festival in Yogyakarta, and playwright/director Le Quy Duong’s many Vietnam festivals, including Hue Drama Festival. In the Philippines, new writing has been enhanced by the annual Virgin Labfest held at the Cultural Center in Manila, and the annual Palanca Literary Awards that began in the 1950s. In 2015, Singapore ambitiously produced 50 Plays to celebrate its 50 years of independence, and Malaysia celebrated 30 years of its Five Arts Centre with an impressive volume of its plays. Festivals abound in the region, often themed and with conferences included, creating meeting places and sharing and often featuring collaborative work. Thailand recently gave a Lifetime Achievement Award to its most prolific playwright, a woman, Daraka Wongsiri, and Singapore’s Haresh Sharma, honoured with a cultural medallion, is one of the most published playwrights in all of Asia. Writing Prizes – such as the SEA Writers Award – are common and often prestigious, remunerative and encouraging. But, as any playwright will tell you no prize is better than being accorded a fully mounted production.

Most plays in this collection have never been published, and some are chosen from a very small pool of available recent plays (Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar are taking early steps) but all plays are relatively new and one, Frangipani, is the writer’s first play. These are not necessarily representative plays (rarely possible with a single work) but are by significant playwrights whose work can be further explored. Floy Quintos of the Philippines and Alfian Sa’at of Singapore are both prolific and nationally acclaimed and enjoy the benefits of a culture that is rich in publications, something shared with Malaysia, where Ann Lee is one of many important writers. But there are crucial differences, and each country deserves its own collection in English.

Theatre taste was not obviously influenced by colonisers, though I believe the British and the Spanish did much to share a love of written literature; and though the Philippines still performs zarzuelas and has a love of western musicals, every Asian country has its own ancient equivalent of musical theatre. Every country has a long history of telling its own stories and Southeast Asia is home to several huge ancient oral epics. In the Philippines, where the longest oral epic of all is still being collected, there is a focus on biographical plays – for examples I commend the many dramatisations of the life of their national hero, José Rizal. But some stories are still best told as fiction or as metaphor, and political leadership is explored this way in Quintos’s An Evening at the Opera and in The Night of the Minotaur from Thailand’s Tew Bunnag. The latter reveals something which is not uncommon: a familiarity with the myths and literature of the West.

Remarkably, Indonesia preserves dozens of regional forms of Wayang, or traditional performance, alongside a range of innovations; unique in Asia, its contemporary work manages to be very modern without showing any distinct Western influences. Protest literature is familiar not only in the Philippines, where it seems to grow stronger, but in all the countries included here; plays approaching once-taboo subjects, such as gay issues and feminism, have done much to help change perceptions and modernise societies. National identity is a common subject of newly independent countries, and plays about various legal and political decisions have all contributed to building the often difficult road to democracy.

At the geographic centre of SEA, Brunei has ancient roots but its modern theatre, growing from an active university, is finding relevance and innovation. Immense internal conflicts have made it difficult for Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos to build new literary or dramatic forms or even preserve old ones, but support groups such as the one around Chhon Sina in Cambodia are finding ways to develop writers’ voices and build audiences. Vietnam and Indonesia have had remarkable success in retaining traditions whilst developing new ways, and though full-time writers are few, the wealth and diversity is impressive. The old French and Dutch colonisers left little love of literature, so credit must go to the people and their intent on modernizing and ensuring that vernacular, dialects and eloquent language is equally valued, along with ideas. Dang Chuong’s Dark Race is refreshingly welcome, as it shows a progressive Vietnam that feels quite familiar, as does Joned Suryatmoko’s Piknik: in portraying Javanese in Bali, it reflects the problems of foreign workers anywhere. These are all plays of ideas, selected for a work’s ability to traverse national barriers and communicate out of context.

Thailand is actively building spoken drama, though its lack of translations still keeps its best qualities hidden. Unique in Asia as never having been colonized, Thailand has always valued performance, and its dance and dance dramas, Lakhon and Khon come readily to Westerners’ minds; but the modern nation and its people are much more evident on its stages than traditional performance, which is sought mainly by the tourists. Interesting also is the growth of English-speaking theatre in Thailand; and that modern drama training can be found even in the provinces.

Though Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines share race and language origins, and cultural links are found everywhere in SEA, essential differences between the nations are numerous; but when it comes to the problems facing playwrights and new writing, there are many shared situations and dilemmas. Government funding of new work excels only in Singapore, and generally there are messy copyright laws and few incentives to encourage playwrights; and almost everywhere spoken drama is more interdisciplinary than pure: it is in transition to new expressions and is determined to strengthen. Political will is not always evident, and often in flux: a good example being Singapore, where priority was deliberately given to economy building, and only more recently are the arts valued as crucial to a robust society. But across the region, where security, employment and education are growing, so are the arts.

Many people have helped us find these works, and we know that this publication is only a glimpse into what is available. It is exciting to discover the other forms of play-making that exist in this region but we regret our inability to include, for example, the wonderful Indonesian work that is commonly improvised afresh with every performance. Similarly, we have not included works which rely upon the use of several languages, such as Koes Juliadi’s Clay Women of Kasongan, or which are too locally-specific, or have specific performance styles or large musical or dance elements. But it is no accident that this collection includes many plays by women, and this is a sign of the equity that has emerged as a feature of these ancient-yet-young nations. Nations that are growing in pride, in industry, investment and in tourism, in innovation and in cultural originality.

Aubrey Mellor OAM

Lasalle College of the Arts, Singapore, 2016.

PLUNGE

JEAN TAY

First produced in 2001 by Action Theatre in Singapore.

Directed by Krishen Jit.

Characters

ISABEL – a young Singaporean woman in her mid-20s, newscaster

INA – a young Indonesian Chinese woman in her early 20s

CHORUS – made up of 3 men: Man A, Man B, and Man C

Setting

Asia.

Time

2 July 97 to June 98.

Headings marked with [ ] may optionally be projected on-screen.

ACT ONE: FUNDAMENTALS

SCENE 1: DESCENT

Gongs begin chiming in the darkness.

They continue to chime until they blend into the sound of the opening music coming on for the Seven O’Olock News.

Lights gradually come on during the news. We can see the shadowlit silhouette of the newsreader. Projected behind her is a landscape of gleaming silver skyscrapers, the central business district. Everything about it speaks of progress and efficiency. The stage is full of modern, high-tech wide-screen television sets, on which we can also watch the news.

The music for the Seven O’Clock News gradually fades away as the lights brighten on the newsreader and we can see her, wearing a pastel green Chanel suit. She has the clean, sculpted, impeccably made-up features and coiffured hair of your typical newsreader. Her voice is equally flawless, trans-atlantic, hint of an American/British accent, crystal clear and emotionally disengaged. Her face is reflected in the many television sets around the room as she reports the news:

Good evening. Welcome to Channel 5.

This is Isabel Cheong, bringing you the Seven O’Clock News on the 2nd July 1997.

The Thai baht plunged to a record low against the dollar today, after the government floated the currency, ending uncertainty over Thailand’s exchange rate policy. The flotation devalued the baht by fifteen to twenty percent while the Stock Exchange fell by seven-point-nine percent. It’s the latest in a series of surprise measures by authorities trying to boost the economy, which is suffering its worst slump in over a decade.

She pauses. Lights dim on her, although she can still be seen. The spotlight brightens on Man A, who stands like a pillar through his following monologue. While he speaks, she adjusts her make-up, blouse, shuffles through her papers etc.

I had a dream last night.

I was waiting for a lift, when I heard the soft musical chime of approach.

The silver doors slid open and I stepped into a world of mirrored walls and marbled floor.

I press the button that says ‘G’ for ground, and it lights up, a warm orange.

The doors slide shut, and I am arching my neck upwards to see the orange light flee from one circle to the next.

Then I feel a terrifying lurch, and gravity yanks my heart from my body.

The solid floor gives way.

And the orange lights are flying, sparking over all the buttons.

I am in free fall.

And my body cannot catch up.

I ricochet off the walls of the elevator.

There is no floor, there is no ground.

I plunge straight into the centre of the earth.

Straight towards ‘G’ for gravity.

And when I finally think it is all over, when we hit ‘G’ and I think I can finally breathe again… It doesn’t stop there.

I keep falling.

Lights fade on Man A, and brighten on Isabel.

Indonesia succumbed to speculative attacks and floated the rupiah today. The rupiah dove on the news, plunging about four percent, while Indonesian stocks dropped to a thirteen week low.

Again she pauses as lights dim on her. Spotlight on Man B as he gives his monologue.

I had a dream last night.

I dreamt that I was standing on the edge of a suspension bridge.

A bridge between two separate lands, an umbilical cord of steel and asphalt, across a swelling river. Strong enough to carry eighty cars at a time, with waves cresting twenty feet below.

I stand at the edge, exhaust in my hair, my hand wrapped around the ropes of steel, my pocket full of change to pay the toll.

And as I look down, a crack snakes beneath my shoes.

Solid ground shatters like eggshell.

And I am in free fall.

Steel rivets and shards of asphalt splinter past my face, scratch my skin.

And when I feel I must finally stop, when my heel finally slaps hard surface.

It doesn’t stop there.

I crash through the ragged face of the water, the weight of the coins in my pocket pulls me down.

Until I am completely wrapped in water, and all my orifices sealed.

But it doesn’t stop there. I keep falling.

Lights fade on Man B, brighten on Isabel again.

The South Korean won ended at a record low this afternoon, after the government declared that it would no longer defend the currency.

The won smashed through the psychologically significant one thousand dollar level in a single breath, while the stock index lost more than four percent.

I had a dream last night.

I dreamt that I was standing on top of a huge metal crane.

A lattice of bright silver with a hook of gold.

A machine that moved mountains, and I, borne aloft at its rearing head.

And as I watched, my feet booted and head helmeted.

The crane blurred, tarnished, and turned a coppery red.

Rust creeping up the edge of metal.

The scabs crumbling across my boots.

And beneath me, metal eaten as if by acid.

The teeth marks growing deeper by the moment.

The scarred, dissolving flesh of a leper.

This skeleton crumbles.

And I am in free fall.

And a dozen half-built office blocks rise to impale me. With their sharpened columns glinting in the sun.

And my body is shattered into a thousand separate pieces.

Flesh pulled from bone, severed from teeth.

But it doesn’t stop there. I keep falling.

And that’s all that we have time for tonight. I’m Isabel Cheong, thank you for joining me. The next news bulletin will be at ten o’clock tonight. Have a pleasant evening.

Music blares on as the news bulletin comes to an end, and the lights dim on her. We see her silhouette, gathering her papers, shuffling them. The skyscrapers are bright behind her. She stands up, still looking through her papers.

Finally, she extracts a single sheet, and lights go out on her. But, the television set (or television sets) are still on, and she is still on air, speaking, although the sound is turned off. The men now hover around the television sets, gazing at her in worshipful adoration.

SCENE 2: ADORATION

Isabel darling, you were wonderful tonight.

Isabel, it was amazing.

Heaven, Isabel, heaven.

The way you raised your eyebrow, just then. Just like that.

You said controversy, just the way it should be said.

That divine brooch you wore.

You lifted the corners of your lips. A smile, just barely.

Con-TRAW-ver-sy. Not con-troh-VER-see.

And the suit. What an ensemble.

Very Mona Lisa. With Gauguin eyes.

I’ve never met someone who ennunciated the way you do.

That apple green is so you.

And that briefest bob of the head, when you said goodnight.

You hit Michel Camdessus. Ryutaro Hashimoto. Chavalit Yongchaiyudh. Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie. Effortlessly.

Nothing less than Chanel, am I right?

Acknowledging, bringing us in, yet keeping that distance.

And the EDB, PIE, MOE, AYE, ERP, TDB, NWC. Not a stumble.

And the diamond-studded ears. Understated, yet classy.

You are the most amazing woman. Ever.

Your voice inspires me to new heights.

I would do anything for you, you know.

If you asked me to, I would set myself on fire.

Jump from the tallest building

Die for you.

I can’t help it. I can’t help falling.

Lights fade. A juke-box tune comes on, some tune along the lines of ‘Can’t Help Falling in Love’.

SCENE 3: NAME

Isabel has taken off her jacket. She is now Ina, in a simple tank top, hair tied into a limp ponytail, without make-up. Ina may be the same age as Isabel, or slightly younger. Lights fade up on Ina, who looks nervous and young, and clutches a single sheet of paper to her chest.

Ina speaks with a distinctly Indonesian accent, and we can almost hear her struggling at times with the language. Ina holds out a piece of paper, with two Chinese characters written on it. It is the same piece of paper that Isabel earlier extracted from the stack on her desk.

Hello. My name is Ina. I live in Jakarta and I study in the university. I would like to be a civil engineer. Not many girls study that, but I think it is very… powerful.

You see a rubbish heap or construction site, full of trash. Pieces of wood, buckets of concrete, broken glass and twisted wires. It’s a mess. Disgusting. Dirty.

But then… but then you start to put the pieces all together, and slowly, it turns into something beautiful. Shining. All straight edges. Nothing crooked, or dirty or twisted any more. All you need is the knowledge. To put it together. Fit the jigsaw together. Every nail, every screw has its place.

That’s power. I think. Putting together. (Pauses)

I have another name. But I don’t use a lot.

It sounds like Ina too, but it looks different.

She takes out the piece of paper with the Chinese characters on it, and shows it to the audience.

This is my name. Ina. Ai nah.

Isn’t it beautiful? Ai nah.

You see the strokes? Like the eyebrows of a beautiful woman.

Thick and strong. Tapered.

They arch from one end of the page to the other.

But if you take them apart, they are nothing more than ink stains on white paper.

A dirty piece of paper, that you crumple up and throw away.

But it’s only when you put them together, the right way, then every speck has meaning.

Every flick of the brush tells you something.

You put them together, and that’s me.

You see? Ina.

She pauses, as the men emerge, their shadows looming over her. Over Ina’s following monologue, they murmur very softly the three official documents, or perhaps, it is projected over her.

My father doesn’t like me to use my Chinese name.

He’s a stern man, my father. Not the kind that hugs his children or kisses them.

And he doesn’t like people speaking Chinese around the house.

I guess that’s why he never taught me any.

I never learnt.

Can’t write, can’t read.

My grandmother wrote that for me. A long time ago.

I don’t know what it means.

It’s just a bunch of black marks.

Beat.

But not just.

The Three Laws

The ‘Presidential Instruction on Chinese Religion, Beliefs and Traditions’, states that manifestations of Chinese religion and belief can have an “undesirable psychological, mental and moral influence on Indonesian citizens as well as obstruct the process of assimilation.” It bans celebration of Chinese religious festivals in public and states that religious practice of Chinese traditions must be kept indoors or within the household.

‘Instruction of the Ministry of Home Affairs No. X01/1977 on Implementing Instructions for Population Registration’ authorises special codes to be put on identification cards indicating ethnic Chinese origin.

‘Circular of the Director General for Press and Graphics Guidance in the Ministry of Information on Banning the Publication and Printing of Writings and Advertisements in Chinese’: restricts any use of Chinese to a single newspaper called Harian Indonesia, on the grounds that dissemination of materials in Chinese will obstruct the goal of national unity and the process of assimilation of ethnic Chinese.

As Ina finally stops talking, the chorus speak at their normal volume, almost tenderly.

I am protecting you from everything that makes you not me.

I am allowing you to assimilate, to ease the process of adjustment.

I am protecting you from things that may backfire.

From passions that may be incensed.

From glass that may cut.

From fires that may burn.

I am trying to protect you.

If I could have held you then, I would.

If I could have kept you safe, I would.

I would keep you from falling.

From burning.

From dying.

As they speak, the lights gradually fade on the men too, until it is completely dark.

SCENE 4: THEORY A (APPLE)

Lights come up on Man A, who has put on a pair of glasses to look professorly. There are all sorts of professional-looking charts and tables projected behind him. The music continues playing in the background as Man A speaks.

Ladies and Gentlemen.

I know. You all want to know why. Why?

And so, I will tell you why. I will explain to you exactly and precisely why the Asian economic crisis happened as it did. For this, I need a volunteer. Preferably one with some kind of fruit in hand. Preferably a fruit that is of sufficient toughness and resiliency. Preferably an apple. Do I have a volunteer, please?

Yes, you sir!

You have an… No, that’s an orange. That’s not going to work. I need someone with an apple. That’s right, a crisp, crunchy, fresh, delicious, shiny, ruby-red apple. Do I have a volunteer? Yes? No?

Yes, you have an apple sir? You do? That’s quite perfect! Come on up here sir, and let’s all get to know you.

And what’s your name sir?

Cecil.

Cecil. What a lovely name. And that is a lovely red apple.

Thanks.

Thank you sir, for coming up here to facilitate my demonstration. Now if I could have the apple, please. If you could just sit on the floor here. Lovely, lovely. Right. May I? Thank you. (He clambers onto a chair, and towers above Man C)

Now Ladies and Gentlemen. Observe up here, a beautiful red apple.

And a man. Down there.

Excuse me, sir?

Yes?

You’re not… Are you?

What?

Man C looks at the apple raised over his head. Man A follows his gaze, and then laughs.

Oh no, no. My dear man, what were you thinking? I wouldn’t dream of causing you any pain.

No?

No.

That’s good.

Of course not. I promise. Anything you may experience will be completely theoretical.

Yah?

Oh yes. In theory, this will be entirely painless.

Now as I was saying, ladies and gentlemen. The apple. And Cecil.

Two possibilities. Or maybe three.

When I release this apple…

A) It will fall downwards, and hit my friend Cecil on the head.

B) It will stay there suspended in mid-air.

C) None of the above. In other words, it could fly straight up like a helium balloon or an American bald-eagle. Or it could trace an elliptical orbit around my head. Or burst into flame. Or explode into a thousand little pieces.

There are a hundred, a billion things this apple could do. The possibilities are limitless. Why, when it could do so many other exciting things, should it fall?

Apart from this little theory that some of you may be familiar with.

In classical mechanics, it’s known as the universal force of attraction that affects all matter. Some call it gravity. A law of physics.

And yet, what are laws but rules waiting to be broken?

I posit that this is what happened in the Asian currency crisis.

What went up finally came down, and came down spectacularly.

Did it have to? Of course not. It could have done a hundred, a billion other things. But did it do those billions of things? No. And why? I say gravity.

Shall we see the proof? Of course. Everything sounds good in theory. Hypothetically.

Now. In the words of Sir Issac Newton himself.

He releases the apple, and it hits Man C squarely on the head.

Ow!

I rest my case.

The music, which has faded to the background, gradually comes on again, until it drowns all other things.

ACT TWO: PANIC

SCENE 1: CHEERLEADING

The music for the Seven O’Clock News blares on again, a little too loud and annoying. A huge trading screen is projected in the background, with the flashing green numbers of currency and share prices. This act has the frenetic energy of a busy trading floor. The three men hold bright, fluorescent pom-poms and cheer on their currencies like all-American cheerleaders. They are extremely hyper, as they go through their desperate, energetic cheerleading routine, and every gesture can be interpreted as a motion to buy/sell. Isabel sits at her desk as usual, reading the news.

Good evening and welcome back. This is Isabel Cheong with more on the Asian currency meltdown.

Asian currencies plunged as confidence in the region deteriorates.

After more than thirty years of explosive growth, this crisis is taking the Asian Tigers by surprise. Investors are starting to panic.

Ready guys?

Ready!

Tell me, what’s the bottom line?

The dollar sign!

I can’t hear you! What’s the bottom line?

The dollar sign!

The dollar sign?

The bottom line! Yeah!

(July 2) Thailand floated the baht in a bold move which sent shock waves through Southeast Asia today. This resulted in a twenty percent plunge in the baht.

What are we waiting for?

You got the stripes! (Clap clap)

You got the claws! (Clap clap)

You got the stripes you got the claws!

Go tigers! Yeah!

(July 24) Asian currencies plunged to new depths on Thursday. The Thai baht, which led the decline, hit a low of thirty-two-point-seventy to the dollar.

I’m a tiger, hear me roar! I’m not gonna hit the floor! (They roar)

(August 14) Indonesia succumbed to speculative attacks and floated the rupiah, which plunged by four percent after markets opened.

Go tigers, go tigers, go tigers!

(September 4) Asian currencies plunged on the news. The ringgit dropped by more than four percent in two hours as Malaysia renewed calls for a ban on currency trading.

Bloody foreign speculators!

Just get lost!

Stupid morons!

S-O-R-O-S, what do you get?

M-O-R-O-N, that’s what you get!

Who’s immoral? Guess!

Who’s a cheater? Who!

S-O-R-O-S the M-O-R-O-N!!!

And now, a word from our sponsors.

SCENE 2: TIME OUT

[Playwright’s Disclaimer: No numbers were actually hurt in this reconstruction.]

Only the numbers plunge.

Only on paper.

Only those who believe.

That the numbers are real.

That you can wrap your arms around an eight hundred million dollar exchange rate loss.

That a five percent decline means your fingers are falling off.

A ten percent fall means you lose your arms up to your elbows.

A twenty percent drop means the amputation of both legs.

A thirty percent plunge means you lose all limbs.

You don’t live beyond thirty percent.

You can’t.

You start to lose your vital organs.

The liver, the kidneys, the stomach, the heart.

You lose eighty percent, and you’re just a brain in a jar, on somebody’s desk.

[End of Time Out]

Lights up on Ina onstage, watching the news on one of the TV screens perhaps.

Nowadays, very exciting times. You read newspapers, listen to news, hear what they say. Other worlds so different from me. Men in long-sleeve shirt and tie, making decisions, business deals. Not just thousands or tens of thousands. But millions of dollar deals. Sometimes even billions. Numbers so big, they don’t make sense after a while.

And just like that. At the click of a button, just one word from their mouths.

That’s why my father says, no point investing in the stock market. So risky, the wind change just like that. And people lose everything, it’s out of their control.

He prefers to make money the old-fashioned way. Small business, hard work. You don’t earn that much, but you get to know your customer well, and if you work hard, do things the right way, you’ll be OK. You’ll be safe.

And that’s what’s important.

Lights dim on Ina. They brighten again on Isabel at her desk, and the three men, who are taking a breather. The men wearily get back on to their feet again and prepare to do another round of cheerleading.

Welcome back to the Seven O’Clock News. (Nov 17) We now turn to South Korea, where the currency was sent smashing through the one thousand won per dollar level this morning.

You won, baby, won, baby, you want the won!

(November 19) Determined to save its currency without turning to the IMF, the South Korean government announced a sweeping set of measures to stem the country’s crisis.

I won, baby, won, baby, I want the won!

(November 20) The response to South Korea’s self-rescue measures was not encouraging. After half an hour of trading the won plunged to one thousand, one hundred and thirty-nine won per dollar.

The men huddle discussing cheerleading strategies. They try again:

Give me an I! (I!) Give me an M! (M!) Give me an F! (F!)

What do you get? Cash!

I can’t hear you! Cash!

I-M-F! Cash!

(December 4) Seoul stocks saw its largest single day gain after Korean officials and the IMF signed a letter of intent promising Korea fifty-seven billion dollars.

They start to sing and dance the I-M-F-Cash number below to the tune and in the style of the song ‘Y-M-C-A’.

We’ve got to go to the I-M-F-Cash

We’ve got to go to the I-M-F-Cash

They have everything there that you need to enjoy

We can hang out with all the boys.

It’s fun to be at the I-M-F-Cash

Labour unrest in South Korea has been sparked off by IMF demands for tougher laws on layoffs.

A factory worker at a South Korean shipyard died after setting himself on fire in support of a cancelled general strike.

The men’s moods are dampened. Man C suddenly shouts at Isabel.

Are you happy now? Is that what you want?

Isabel ignores him and reads on.

We now turn to Indonesia, where President Suharto has signed an agreement with the IMF that requires him to dismantle the monopolies and family-owned businesses that marked his thirty-two year rule. But markets were not impressed and the rupiah plunged through the fifteen thousand per dollar level. The currency has lost eighty percent of its value since last July.

Come on, you guys. Looks like the brain’s in the jar, already.

The men try the I-M-F-Cash cheer again, more desperately this time.

Give me an I! (I!) Give me an M! (M!) Give me an F! (F!)

What do you get? Cash!

I can’t hear you! Cash!

I-M-F! Cash!

(February 14) IMF has threatened to cut off funds for Indonesia over its controversial plans to establish a currency board.

Don’t tell me what to do.

(March 6) IMF delays a planned three billion dollar disbursement to Indonesia.

Don’t tell me what to say.

(April 21) Indonesia is launching a series of reform measures agreed to with the IMF.

When I get cash from you

Don’t put me on display

As Isabel continues to read the news, the men react with increasing dismay at the news that she is reading, albeit in different ways.

Man B continues to sing the song, while Man A launches into another IMF cheer, and Man C rants and raves at her. Until they are all overtaken and dominated by the ‘Three Blind Mice’ nursery rhyme song that Isabel is singing.

These measures include the removal of subsidies for fuel and electricity, which will lead to domestic price hikes.

Give me an I! (I!) Give me an M! (M!) Give me an F! (F!)

What do you get? Cash!

I can’t hear you! Cash!

I-M-F! Cash!

Cos I’m strong and I like to be strong

I’m free and I like to be free

To live my life the way I want

To say and do whatever I please.

Why can’t you leave us alone! Leave us alone! What are you trying to do? Shut up! If you’d just stop talking so much! Stop it, you moron! What else do you want from me? My blood? You idiot! You cheat!

ISABEL(continues reporting in her normal tone of voice, even as the content of the news grows more ridiculous)

And Asian currencies plunged again on the news. And Asian currencies plunged.

And plunged. And plunged.

And three blind mice. Three blind mice.

See how they run. (Gradually picking up the tune) See how they run.

They all run after the farmer’s wife, who cut off their tails with a carving knife

Have you ever seen such a sight in your life, as three blind mice?

She continues singing, picking up speed as she goes, and the men, who ignore her at first, start to join in, one by one, singing in rounds. They get more and more frenzied. Lights gradually fade on her, and her voice fades away, until only the men are singing, and running in panic around the room. Finally, they fall down on the floor exhausted.

Lights come up on Ina.

SCENE 3: CRACK

We live without thinking.

Most of the time.

We live without choosing. Don’t even know how to.

I sit at home and read the newspaper, watch the news. About other people.

Other people changing lives, changing things.

Other people making decisions for us.

And look at what happens.

Things can’t go on like this. And they won’t.

This is a chance. A crack in the floor.

And we’re going to go for it.

My classmates and I have decided.

Tomorrow, after school. We’re going to go for the protest rally.

I… I can’t say I wanted to go at first.

But then, I thought about it.

All my life. I’m sitting there, watching someone else live for me.

This is the crack. The chance I have to take.

Lights dim on Ina, though we can still see her standing on stage.

Man A’s voice comes on over the radio. He is a reporter, probably some US correspondent from CNN or something, live at the scene. His voice is breathless, a little hoarse from shouting to be heard, and generally excited to be in the middle of everything. You can hear the sounds of students chanting slogans etc in the background. Perhaps some of the television sets come on too, with scenes of the students rallying peacefully.

I’m now standing outside the campus of the University of Indonesia, where students are rallying peacefully against the recent price hikes as well as for political and economic reforms. Thousands of students are sitting on the road outside the campus, listening to speeches and chanting slogans.

Ina listens intently to the program. Lights now brighten on Ina, who is arguing with her unseen father.

No! No, Papa! I don’t want to.

You cannot tell me what to do.

We are not going to fight. It is not for violence.

It is not for fun. You think we’re so young, so immature.

What am I supposed to do? Stay at home, knit socks like an old woman?

You don’t understand. I’m not going for myself, I’m going for all for us.

I’m 20 years old. I should know what I want.

I’m not being childish.

I’m not.

Don’t be so narrow minded.

If you want to be a coward, go ahead.

Stay at home, lock your doors. Pretend the outside world doesn’t exist.

I shouldn’t even have told you in the first place.

But I thought you’d understand.

That this is important.

We cannot go ahead and let other people lead our lives for us.

Please, papa?

Please? (Pause. Her father obviously disagrees)

Aargh…

She picks up the note in frustration, crumples it up and flings it at her father. Then goes to the corner and sulks.

SCENE 4: THEORY B (BUBBLE)

[Panic Theory]

Lights suddenly come on very bright on Man B. It’s his turn to play professor. Some bubble-gummish tune comes on. Preferably one with references to love, and bubbles or bubbly emotions. (e.g. ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’.)

My respected colleague recently entertained you with his rendition of the Southeast Asian currency crisis. I wish to preface my presentation today, by saying that I have nothing but the utmost respect for my colleague. Unfortunately, this is an area where I beg to differ. Allow me to share my thoughts with you.

My beautiful assistant will be, of course, assisting me.

Man C comes up, dishevelled, rebellious, chewing his bubble gum.

Man B clears his throat, embarrassed.

Austerity drive. What can you do? Will you please get that thing out of your mouth? (Man C looks mutinously at Man B. He scowls) Or else. (Man C grimaces, takes the wad of gum out and sticks it behind his ear) That’s disgusting. On second thought, please put it back in again. (Man C smirks. Puts the gum back into his mouth) Actually, you know, that works out rather well. (Man B gives an unexpected smile) My beau… My assistant will now blow a big bubble for you.

Man C ignores him, still chewing. Man B clears his throat, nudges Man C.

I said, my assistant will now blow a big bubble. (Man C obliges. Man B shakes his head) Nope, not good enough. You’ve got to be able to do better than that.

Man C takes a deep breath and blows a large bubble.

That’ll do. Thank you. Ladies and gentlemen, if you will pay careful attention to this bubble. Note that when it was not so big, it was cloudy and pink.

Opaque, and almost impossible to break.

But pretend that it is bigger. And I mean much much bigger.

Imagine it twenty times the size of this really.

My beautiful assistant has somewhat limited lungs.

But if you can imagine the perfect bubble. About this big.

It would be as clear as glass. You can see all the way through it.

And the lightest, softest touch would cause it to shatter.

If I even breathed upon it, it would burst into a thousand pieces.

So that’s how it happened. How the perfect crisis occurred because of the perfect bubble. Blown so big it is like fine Bohemian crystal.

But the harder you blow, the louder you burst.

And you’re left covered in saliva and chewed up gum.

Man B takes a sharp pointed object, like a long knitting needle, etc. Man C looks worried but doesn’t budge. He mumbles.

Mmm… mmm… mm.

Yes? You wanted to say something?

Man C shakes his head, shrugs his shoulders, tries gesturing, somewhat unsuccessfully.

Mmm mmm mmm.

My dear fellow, if you ever want the sweet taste of success, just once in your life, you’ve got to learn how to enunciate. That’s what your tongue is for. Anyways… (Shrugs his shoulders) Education must go on. Boom.

Man B strikes at the bubble.

Instant blackout. Sound like a gunshot.

Lights come up on Ina who sits, looking very stunned.

They said zero. At first.

Zero. Then One. Or Two.

No. Four. Or Six? I don’t know.

It’s all numbers. I don’t care. It doesn’t make a difference.

Does it? Six. Or Sixty? Maybe six hundred even?

You hear people die in war. All the time. Somewhere in Serbia. Middle East. Somewhere else.

But this is not war. (Pause)

So why are there bullets?

Last I heard was six. But they could be lying.

Everybody lies nowadays.

People talk rubbish all the time. Especially people reading the news.

It’s all rubbish. There should have been zero. Why six?

Out of how many?

It doesn’t matter. Six out of six. Six out of six hundred. Six out of six thousand.

Only if you are one of the six. If you loved one of the six. Knew their name. Their face. Or shared a joke with them in class. Borrowed their notes.

Or kissed them on their forehead, like a blessing. Or a curse.

But just six. Not seven. Maybe.

Because I was here. Not there.

Later, at night. I couldn’t sleep. But I lay in bed, thinking.

My father came into my room. So I pretended to be asleep.

He stood there for a while.

Then he whispered something. I’m not sure what it was, but I think it was my name.

He stood for a little while more and then went out again.