Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

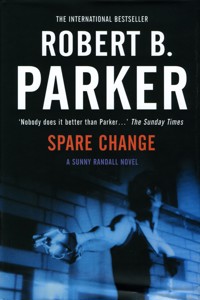

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Sunny Randall Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

When a serial murderer dubbed "The Spare Change Killer" by the Boston press surfaces after three decades in hiding, the police immediately seek out the cop, now retired, who headed the original task force: Phil Randall. As a sharp-eyed investigator and a doting parent ("You're smart. You're tough. You, too, are a paradigm of law enforcement perfection, and you're my kid"), Phil calls on his daughter, Sunny, to help catch the criminal who eluded him so many years before. Sunny is certain that she's found her man after interviewing just a handful of suspects. Though she has no evidence against Bob Johnson, she trusts her intuition. And she knows the power she has over him - she can feel the skittishness and sexual tension that he radiates when he's around her - but persuading her father and the rest of the task force is a different story. When the killer strikes a second and third time, the murders take a macabre turn, as the victims each eerily resemble Sunny. While her father pressures her to drop the case, Sunny's need to create a trap to nab her killer grows. In a compelling game of cat-and-mouse, Sunny uses all her skills to draw out her prey, realizing too late that she's setting herself up to become the next victim.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 265

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

When a serial murderer dubbed “The Spare Change Killer” by the Boston press surfaces after three decades in hiding, the police immediately seek out the cop, now retired, who headed the original task force: Phil Randall. As a sharp-eyed investigator and a doting parent (“You’re smart. You’re tough. You, too, are a paradigm of law enforcement perfection, and you’re my kid”), Phil calls on his daughter, Sunny, to help catch the criminal who eluded him so many years before. Sunny is certain that she’s found her man after interviewing just a handful of suspects. Though she has no evidence against Bob Johnson, she trusts her intuition. And she knows the power she has over him — she can feel the skittishness and sexual tension that he radiates when he’s around her — but persuading her father and the rest of the task force is a different story.

When the killer strikes a second and third time, the murders take a macabre turn, as the victims each eerily resemble Sunny. While her father pressures her to drop the case, Sunny’s need to create a trap to nab her killer grows. In a compelling game of cat-and-mouse, Sunny uses all her skills to draw out her prey, realizing too late that she’s setting herself up to become the next victim.

Robert B. Parker (1932-2010) has long been acknowledged as the dean of American crime fiction. His novels featuring the wise-cracking, street-smart Boston private-eye Spenser earned him a devoted following and reams of critical acclaim, typified by R.W.B. Lewis’ comment, ‘We are witnessing one of the great series in the history of the American detective story’(The New York Times Book Review).

Born and raised in Massachusetts, Parker attended Colby College in Maine, served with the Army in Korea, and then completed a Ph.D. in English at Boston University. He married his wife Joan in 1956; they raised two sons, David and Daniel. Together the Parkers founded Pearl Productions, a Boston-based independent film company named after their short-haired pointer, Pearl, who has also been featured in many of Parker’s novels.

Robert B. Parker died in 2010 at the age of 77.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR ROBERT B. PARKER

‘Parker writes old-time, stripped-to-the-bone, hard-boiled school of Chandler… His novels are funny, smart and highly entertaining… There’s no writer I’d rather take on an aeroplane’ – Sunday Telegraph

‘Parker packs more meaning into a whispered “yeah” than most writers can pack into a page’ – Sunday Times

‘Why Robert Parker’s not better known in Britain is a mystery. His best series featuring Boston-based PI Spenser is a triumph of style and substance’ – Daily Mirror

‘Robert B. Parker is one of the greats of the American hard-boiled genre’ – Guardian

‘Nobody does it better than Parker…’ – Sunday Times

‘Parker’s sentences flow with as much wit, grace and assurance as ever, and Stone is a complex and consistently interesting new protagonist’ – Newsday

‘If Robert B. Parker doesn’t blow it, in the new series he set up in Night Passage and continues with Trouble in Paradise, he could go places and take the kind of risks that wouldn’t be seemly in his popular Spenser stories’ – Marilyn Stasio, New York Times

THE SPENSER NOVELS

The Godwulf Manuscript

Chance

God Save the Child

Small Vices*

Mortal Stakes

Sudden Mischief*

Promised Land

Hush Money*

The Judas Goat

Hugger Mugger*

Looking for Rachel Wallace

Potshot*

Early Autumn

Widow’s Walk*

A Savage Place

Back Story*

Ceremony

Bad Business*

The Widening Gyre

Cold Service*

Valediction

School Days*

A Catskill Eagle

Dream Girl (aka Hundred-Dollar Baby)*

Taming a Sea-Horse

Pale Kings and Princes

Now & Then*

Crimson Joy

Rough Weather

Playmates

The Professional

Stardust

Painted Ladies

Pastime

Sixkill

Double Deuce

Lullaby (by Ace Atkins)

Paper Doll

Wonderland (by Ace Atkins)*

Walking Shadow

Silent Night (by Helen Brann)*

Thin Air

THE JESSE STONE MYSTERIES

Night Passage*

Night and Day

Trouble in Paradise*

Split Image

Death in Paradise*

Fool Me Twice (by Michael Brandman)

Stone Cold*

Killing the Blues (by Michael Brandman)

Sea Change*

High Profile*

Damned If You Do (by Michael Brandman)*

Stranger in Paradise

THE SUNNY RANDALL MYSTERIES

Family Honor*

Melancholy Baby*

Perish Twice*

Blue Screen*

Shrink Rap*

Spare Change*

ALSO BY ROBERT B PARKER

Training with Weights

A Year at the Races (with Joan Parker)

(with John R. Marsh)

All Our Yesterdays

Three Weeks in Spring

Gunman’s Rhapsody

(with Joan Parker)

Double Play*

Wilderness

Appaloosa

Love and Glory

Resolution

Poodle Springs

Brimstone

(and Raymond Chandler)

Blue Eyed Devil

Perchance to Dream

Ironhorse (by Robert Knott)

*Available from No Exit Press

For Joan: once in a lifetime

1

I sat with my father at the kitchen table and looked at the old crime-scene photographs. Four men and three women, each shot behind the right ear. Each with a scatter of three coins near their head as they lay on the ground. There was in the implacable crime-scene photography no sense of lives suddenly extinguished, fear suddenly snuffed, no smell of gunshot or sound of pain. Just some dead bodies. The pictures were accurate and inclusive, but they distanced me from the subject. I didn’t know if it was me or the process. Paintings didn’t do it.

‘The Spare Change Killer,’ I said.

My father grunted. ‘Papers liked that name,’ he said.

‘Because of the coins, we thought at first maybe the perp was a panhandler, you know? “Spare change”? And when the guy starts to give him some, the killer pops him and he drops the coins.’

‘Pops him in the back of the head?’ I said.

‘Yeah, that sort of bothered us, too,’ my father said. ‘But you know how it goes. You got something like this, you try out every theory you can.’

‘I remember this,’ I said.

‘Yeah, you were about twelve,’ my father said, ‘when it started. And maybe fifteen when it was over.’

‘My memory was of how much you weren’t home,’ I said.

My father nodded.

‘And then it just stopped,’ I said. My father nodded again.

‘And you never caught him?’ I said.

My father shook his head.

‘Maybe this time,’ he said.

‘You think it’s the same guy?’ I said.

‘Don’t know,’ my father said. ‘Same bullet behind the ear. Same spare change on the ground.’

‘Same gun?’

‘No.’

‘Doesn’t mean much,’ I said. ‘He could certainly have acquired another gun.’

‘There were different guns in the first go-round,’ my father said. ‘Spare Change said he liked to experiment.’

‘He wrote you?’ I said.

‘Regularly.’

‘You specifically?’ I said.

‘I was the head of the task force,’ my father said. ‘FBI, State, Boston Homicide.’

‘God,’ I said. ‘I didn’t even remember that there was a task force.’

‘You were pretty much caught up in puberty at the time,’ my father said.

‘Boys were pretty much everything I was interested in,’ I said.

‘But now?’

‘The boys are older,’ I said.

My father shrugged.

‘Progress, I guess,’ he said.

‘Why were you in charge?’ I said.

‘First two murders were in my precinct,’ my father said.

‘Plus, of course, I was the very paradigm of law-enforcement perfection.’

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Yes that, too.’

‘Since I retired,’ my father said, ‘I been reading a lot. Even books with big words. I been dying to say paradigm.’

‘I’m proud to call you Daddy,’ I said.

He took a big manila envelope from a pile on the table and opened it. He took out a crime-scene photo and a letter, and put them on the table in front of me. The photograph was just like the other crime-scene photos. In this case a young black man was sprawled on the ground, facedown. There was a dark spill of blood around his head. A nickel, a dime, and a quarter lay in the blood.

‘The new one?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ my father said. ‘Read the letter.’ The letter said:

Hi, Phil,

You miss me? I got bored, so I thought I’d reestablish our relationship. Give us both something to do in our later years. Stay tuned.

Spare Change

It was neatly printed in block letters on plain white printer paper by someone probably using a fine-point Sharpie.

‘Sounds like him?’ I said.

‘Yes.’

‘Anything from the paper, or the ink, or the handwriting?’

‘Nothing from the paper and ink. Possibly the same handwriting. Block printing is hard. Probably right-handed.’

‘You’d guess that from the shot being behind the vic’s right ear,’ I said.

‘You would.’

‘So there’s nothing to say this isn’t the same guy?’

‘No,’ my father said. ‘I tried to keep his letters to me out of the papers, but I couldn’t. The case was too hot. Some cluck in the mayor’s office released them.’

‘So anyone could copycat it,’ I said.

‘It’s not a complicated writing style,’ my father said.

‘You’re back in this?’ I said.

‘Yes. They’ve asked me to consult. Even gave me a budget.’

‘And you want to do this?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ my father said.

I nodded and didn’t say anything.

‘And I want you to help me,’ my father said.

‘Because?’

‘You were a cop. You’re smart. You’re tough. You’re pretty.’ My father grinned at me. ‘You, too, are a paradigm of law-enforcement perfection, and you’re my kid.’

I looked at him across the flat, deadly photographs. He was a thick, squat man with big hands that always made me think of a stonemason.

‘Because I’m pretty?’ I said.

‘You get that from me,’ he said. ‘Will you help?’

‘Daddy,’ I said, ‘I’m flattered to be asked.’

2

It was Monday morning. My bed was made; the kitchen counters gleamed. I had applied makeup carefully, taken a lot of time with my hair. The loft had been vacuumed and dusted, and there were flowers on the breakfast table. I was wearing embroidered jeans so tight that I’d had to lie down to put them on. My top was a white tee that drifted off one shoulder. I’d been doing power yoga with a trainer, and I was happy with the way my shoulders looked. My shoes were black platform sneakers that bridged the gap between casual and dressy in just the right way. Richie brought Rosie back from her weekend visit on Monday mornings, and it takes a lot of work to look glamorous when you are trying very hard to look as if you aren’t trying to look glamorous.

When they arrived I was casually painting under my skylight while the sun was good, and had been for a good five minutes. I put the brush down and picked Rosie up when she came in, and kissed her on the nose while she squirmed and wagged her tail and let me know simultaneously that she was thrilled to see me and wanted to be put down. I put her on the floor.

‘Place looks great,’ Richie said.

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Thanks.’

‘You do, too.’

I smiled.

‘Oh,’ I said. ‘Thanks.’

Richie put a paper bag on the breakfast table next to the flowers.

‘What’s in there?’ I said.

‘Coffee,’ Richie said, ‘and some corn and molasses muffins.’

‘Did you have in mind sharing?’ I said.

‘Sure,’ Richie said.

He opened the bag and took out two big paper cups of coffee and four muffins.

‘Corn and molasses,’ I said. ‘My total fave.’

Rosie went to her water dish and drank loudly and at length. I sat at the counter with Richie and picked up a muffin.

‘Did my kumquat have a good time?’ I said to Richie.

‘She did.’

‘Did she go for walks?’

‘Yes. We took her out every day on the beach.’

‘We being you and the wife.’ Richie nodded.

‘Kathryn,’ Richie said.

I nodded. ‘And she likes Rosie?’

‘She does.’

‘Where does Rosie sleep when she’s there?’ I said.

‘In bed with me and Kathryn,’ Richie said.

He had taken the plastic cap off his coffee cup.

‘And she doesn’t mind?’

‘Kathryn? Or Rosie?’ Richie said.

‘Not Rosie,’ I said.

‘Kathryn doesn’t mind,’ Richie said. ‘Love me, love my dog.’

‘Our dog,’ I said.

‘I get her two weekends a month,’ Richie said. ‘I think it’s clear that she’s not mine exclusively.’

‘I know. I’m sorry.’

Richie nodded. He was physically well organized. Maybe six feet tall. Strong-looking. Very neat. He always looked like he’d just shaved and showered. His thick, black hair was short. All his movements seemed precise and somehow integrated. He had a lot of the interiority that my father had. We ate some of our muffins and drank some of our coffee. Rosie eventually finished her water and came over and sat on the floor between us.

‘Do you suppose all bull terriers drink water like that?’ I said.

‘I think it’s some kind of “glad to see you” ritual,’ Richie said. ‘She does it when she first gets to my house, too.’

‘Remember when we first got her?’ I said.

‘Right after we were married,’ Richie said.

‘She was about the size of a guinea pig,’ I said.

‘Maybe not that small,’ Richie said.

‘And we had to be so careful of her at first so as not to roll over on her in bed.’

We were both quiet.

‘You okay?’ Richie said after a time.

‘Sure,’ I said. ‘You?’

‘Yeah,’ Richie said. ‘I’m fine.’

We drank some coffee and ate some muffin.

‘Felix says he gave you a hand with something a while back.’

I nodded.

‘As far as your Uncle Felix goes, I’m still part of the family.’

‘Felix likes who he likes,’ Richie said. ‘Circumstance doesn’t have much effect on him.’

‘I assume that he also dislikes who he dislikes,’ I said.

‘He does,’ Richie said. ‘It is much better to be one of the ones he likes.’

‘I understand that,’ I said.

Richie broke off an edge of his second muffin and ate it.

‘Felix says you had something going with a police chief on the North Shore,’ Richie said.

‘I did,’ I said.

‘And?’

‘Now I don’t.’

‘What was the problem?’ Richie said.

‘He was still hung up on his former wife,’ I said.

Richie nodded. He drank some coffee and put the cup down and smiled at me.

‘You understand that?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I do.’

Richie nodded, slowly looking at the surface of the coffee in his cup.

‘I understand it, too,’ Richie said.

‘Time now,’ I said, ‘for a pregnant silence.’

‘And then chitchat about Rosie some more,’ Richie said.

3

I loved my father. My sister and I had competed with my mother for his attention all our lives. I was thrilled to have him sharing space with me. To be working with him on something important was a kind of victory. It was also odd.

They had an office for him at police headquarters. But he spent a lot of time in my loft. He was on the phone a lot. He was in and out a lot. At the end of the day, we usually had a drink together before he went home. I looked forward to the drink. And I looked forward to his going home.

On a bright, perfect Tuesday morning in early July he called me at seven-thirty, just after I came back from walking Rosie.

‘I’ll pick you up at eight,’ he said. ‘There’s been another one.’

The body had been found in among some tall reeds beside the Muddy River in the Back Bay Fens. It was a man, maybe fifty-five, wearing a powder-blue jogging suit and brand new white sneakers. He’d been shot behind the right ear. There were three coins beside his head. The Boston Homicide commander was there, a big, tough, well-dressed man named Quirk. There were a dozen other cops, and half a dozen members of the press, including two television people.

‘Phil,’ Quirk said.

‘Martin,’ my father said. ‘This is my daughter Sunny.’

‘Captain,’ I said.

We shook hands.

‘So far,’ Quirk said, ‘it’s same-o same-o. Wallet is still with him, a hundred and twenty dollars in it. There’s no sign of sexual activity. No evidence of any assault except the gunshot that killed him. Haven’t, obviously, got the bullet yet. But from the look of the wound, there’s nothing unusual about the weapon.’

My father was looking down at the man. He squatted and pushed blood-stiffened hair aside to look at the wound.

‘A nine, maybe,’ he said. ‘Or a .38.’

‘Sure,’ Quirk said. ‘Maybe a .40. It didn’t exit his skull. So the ME will tell us.’

‘And then what will we know?’ my father said.

‘Nothing much,’ Quirk said. ‘But we should be used to that by now.’

My father nodded.

‘Do a walk-through yet?’ he said.

‘Yeah,’ Quirk said. ‘I’ll have one of the crime-scene guys take you through it.’

The crime-scene guy was a young woman with copper-colored hair, which she wore in a ponytail. We stood with her on the sidewalk near Park Drive. Her name was Emily.

‘Perp must have followed him in here,’ Emily said.

She stepped onto a barely discernible path that led toward the reeds and the river. Daddy and I followed her.

‘He had some scissors with him,’ Emily said, ‘and a shopping bag, with half a dozen cut weeds in it. We figure he was getting himself stuff for some kind of floral arrangement.’

We paused next to some truncated weed stalks.

‘This is where he was cutting the reeds,’ Emily said. ‘Already matched them with the ones in the bag. He was probably going to cut some more, because he still had the scissors in his hand when he was shot. They landed a few feet away from him when he went down.’

‘And he didn’t go down here?’ I said.

‘No.’

Emily led us along the slight path.

‘He moved on, looking for just the right reed,’ Emily said. ‘Down here.’

We were at the crime scene. ‘He found the right reed,’ Emily said. ‘He stopped, started to cut it, and the perp …’

Emily pretended to shoot with her forefinger and thumb.

‘Bang, bang,’ Emily said.

‘Twice?’ Daddy said.

Emily almost blushed.

‘No. Excuse me,’ Emily said. ‘I was just dramatizing. As far as we can tell now, it was one and out.’

My father didn’t say anything.

‘Footprints?’ I said.

Emily shook her head.

‘Ground’s marshy,’ Emily said. ‘And doesn’t hold a print. Even if it did, people come in here all the time. Smoke dope. Drink. Have sex. Cut reeds. Look at birds.’

‘What’s his name?’ Daddy said.

Emily pulled a small notebook from her shirt pocket and opened it.

‘Eugene Nevins,’ Emily said. ‘Lives on Jersey Street. He’s wearing a wedding ring. No one answers his phone, it’s his voice on the answering machine, and the apartment listing is his name only.’

‘Widowed or divorced, maybe,’ my father said.

‘Gay maybe,’ I said. ‘Not a ton of straight men out cutting reeds for a floral arrangement.’

My father nodded.

‘Any next of kin?’

‘Not yet,’ Emily said. ‘We’re looking.’

‘When did it happen?’ Daddy said.

‘We’ll know better after they get him onto the table,’ Emily said. ‘We’re guessing five, six, seven o’clock yesterday evening.’

‘No one heard a gunshot?

‘No one reported one,’ Emily said. ‘Lot of traffic noise all around the Fenway that hour. Summer day everyone’s got the windows closed, a/c on.’

‘You could probably fire off a handgun in Quincy Market at noon, and no one would report a gunshot,’ my father said.

‘It doesn’t sound like they think it does,’ Emily said.

‘And they don’t want what they heard to be a gunshot,’ Daddy said. ‘They got other things to do.’

‘Emily,’ I said. ‘How cynical does that sound?’

‘Captain Randall has earned the right to it, ma’am.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I guess he has.’

4

Rosie and I were both fed and walked for the night. She was asleep on the bed with her paw over her nose, half under a pillow. I was beside her in my pajamas, reading photocopies of letters that the Spare Change Killer had sent to my father twenty years ago.

Dear Captain Randall,

First, congratulations on being named to head the Spare

Change Task Force. It’s a nice name, ‘the Spare Change Killer.’ I like it. And after only two events. Don’t fret. There will be more. Wouldn’t want you to get bored (ha, ha). Do you wonder why I always leave some change at an event? That’s for me to know and you to find out, isn’t it?

Good hunting,

Spare Change

It was laborious block printing, as if the letters were drawn rather than written.

Dear Phil,

You don’t mind if I call you Phil, I hope, now that we’ve begun to establish a relationship. I know you think of me often, as I do likewise of you. I wonder if we’ll ever meet? Of course, it’s always possible that we have met and you don’t know it. You know what they always say, Phil, it’s a small world. Anyway, how’s the investigation going? I like how hard you are working on establishing a pattern. I’m sorry to tell you that from my end, you don’t seem to be getting anywhere.

Let’s stay in touch.

SC

Beside me Rosie snored softly. The overhead lights were off. I was reading in the small circumference of my bedside lamp. The rest of the loft was dark. The only real sound in the loft was Rosie and the soft rush of the air-conditioning. But the sound of the disingenuous voice from twenty years ago seemed to have materialized in the silence and the darkness. It hung in the air of my loft as if I could actually hear it.

Dear Phil,

How are you doing? As I guess you know, I’m doing quite well. The last event was especially good. It’s fun to get them totally unaware. Walking along and then pow! Dead. You suppose that is why I do this, Phil? For the fun of seeing them go down? I bet you’d like to know that. Maybe I don’t even know it … or maybe I do. I’ll be looking for you on the television.

Be good. (Not like me, huh?) SC

I put my hand on Rosie’s flank as she slept beside me. She was warm and solid. I kept my hand on her as I read the rest of the letters. When I was done, I picked up the new letter and reread it. Same block printing. Same voice. Same person? No way to know. Several of the letters had been published in the papers twenty years ago. Anyone who cared to could find them and mimic them. Or the recent one could be authentic, the simpleminded voice connected to the block printing. The way it was written influenced how it sounded. Form and content? I should have paid more attention in freshman comp. Maybe I could find a forensics English teacher.

I put the letters on the floor, and shut off my reading lamp, and lay on my back looking into the darkness, and tried to think obliquely about what I’d read, as if maybe I’d see better if I didn’t look right at it.

No point in trying to think about the old murders. No one had solved them in twenty years. Focus on the new ones. I’m Spare Change.

I’m walking around the city with a loaded gun. It’s much heavier when it’s loaded. I see somebody I want to kill. Do I follow the person? Waiting for my chance? Do I walk up behind the person and pull the trigger without a word? I shoot him only once. I know what I’m doing. I’m confident he’s dead. I put the gun away. I put the coins down. Do I linger and watch from someplace? Do I get a kick out of seeing the body discovered? Watching the cops arrive? Or do I walk away without another glance. Get my enjoyment from the newspaper accounts. The television stand-ups with the crime scene in the background. ‘Glamour-puss TV person reporting live …’ Do I do this for the publicity? To feel important? Why write to Daddy? Why the beloved adversary crap? All the murders, the two new ones, the earlier seven, had in common was that they were done in places where they could be done covertly. I have never broken in to any place and shot someone. I have always been outdoors, in the city, near the public but out of sight. Along the river. Under an overpass. Down an alley. In a public parking garage. Is that how I pick my victims? Wait around in a good place to shoot, and wait for someone to wander by? Or did I preselect on some obscure basis and follow them around until they went someplace where I could shoot them unobserved?

I was right back to why. Why does Spare Change do it? Why leave the coins? They’re not always the same denomination of coins, but always three of them. And why now? After twenty years. If it was the same guy, what caused him to stop? And what caused him to start again? What if it was a copycat? What set him off? Or her. Most serial killers were men. But it didn’t have to be a man.

My eyes had adapted to the darkness, and I could see the outlines of my home. My easel under the skylight. My table and chairs in the bay. My kitchen counter. My silent television. Rosie was small and substantial beside me. My gun was where it always was at night, in the drawer of my bedside table.

5

We met in a big room in the mayor’s office at Boston City Hall. From the outside, Boston City Hall looks like Stonehenge rising in massive isolation in the middle of a big, empty brick plaza. Inside is less welcoming: gray slab stone and harsh light, as if somehow the building were more important than its function.

The mayor was a much more human presence than the building. He presided quite genuinely over the meeting, just as if it wasn’t taking place in a misplaced Gothic castle. The police commissioner was there, and Captain Quirk, and the head of State Police Homicide, Captain Healy. The Commissioner of Public Safety was there, and a man named Nathan Epstein, who was Special Agent in Charge of the Boston FBI office. There was a woman from the Suffolk County DA’s office, and a guy from the AG. There were also assistants and associates of all of these high-ranking people, plus my father, plus his assistant, which was me.

‘As you speak,’ the mayor said, ‘please identify yourselves. I don’t want to waste time now with introductions, and I don’t know if everyone knows everyone.’

He looked around the room. No one objected. The mayor nodded once.

‘We’ll keep a record of the meeting,’ he said. ‘But it will be a private record for our own information. We’re not going to succeed with the Spare Change killings without a free and uninhibited flow of information. So forget turf. And don’t worry about how it sounds. We have a common goal. Hell, a common need. So I urge you to speak freely, and, if I may, I urge you not to bullshit me. Or each other.’

The mayor looked at the Boston Police commissioner.

‘Beth Ann,’ he said, ‘why don’t you start?’

She was a lean woman in a tailored gray suit. Her eyes were pale blue. Her hair was verging on gray. She wore a wedding ring.

‘Beth Ann Hartigan,’ she said. ‘Boston Police commissioner. We’ve been getting good cooperation from our friends at the state level, and from the federal government as well.’

She nodded at Epstein.

‘We have increased police presence on the streets of Boston by a third. We have supplemented our own resources with state officers and federal marshals.’

‘Is it a visible presence?’ the mayor said.

‘That is our hope, but I don’t know. I think to make the public fully comfortable we’d have to flood the city with far more men and women than we have, than all of us have.’

The mayor nodded.

‘Well, the public will perceive what it perceives,’ he said. ‘There are more police persons looking for the killer?’

‘Yes,’ Hartigan said. ‘The absolute maximum number we can pull together.’

‘How about the progress of the investigation?’ the mayor said.

‘Captain Quirk is in charge of that for us,’ Hartigan said. ‘I’ll ask him to address that.’

The mayor looked at Quirk.

‘Go ahead, Captain,’ the mayor said.

‘Martin Quirk, Boston Homicide commander. Progress is too strong a word. We’ve put together a pretty good team to chase this guy down. Special Agent Epstein from the FBI. Captain Healy from State Homicide. Phil Randall, who was in charge of the original case, has come out of retirement to consult for us. Epstein has provided us a profile from the FBI – tells us the killer is a white male, between twenty and forty-five, some education but nothing advanced or specialized. Couple years of college maybe.’

‘How do they know that?’ the mayor said.

‘Place where he did the crimes. Language he uses in his letters to the police.’

Quirk looked at Epstein.

‘Maybe a little guessing.’

Epstein smiled and shrugged.

‘And?’ the mayor said.

‘And we’re nowhere,’ Quirk said. ‘We don’t know who he is. We don’t know why he does it.’

‘What about the coins?’ the mayor said.

‘They may be just to tag the crime,’ Quirk said. ‘Let us know it’s him, something nonincriminating, so if he got picked up and we found change in his pocket it wouldn’t mean anything. Most people have change on them.’

The mayor nodded.

‘Or,’ Quirk said, ‘it may be just something he does to confuse us, and there is no meaning to the coins. Or it may mean something really important to him, but it doesn’t mean anything to anyone else.’

‘Have you had any forensic psychiatry input?’ the mayor said.

‘Yes.’

‘And?’

Quirk shook his head.

‘He kills for reasons we don’t understand,’ Quirk said. ‘We don’t know why he did it twenty years ago. If it’s the same guy. We don’t know why he stopped. We don’t know why it’s started again.’

The mayor looked at my father.

‘Phil?’ he said.

‘Phil Randall,’ my father said. ‘I got nowhere with it first time out. I thought then, and I still think, that what will eventually happen is he’ll make a mistake. He’ll choose the wrong place to do the shooting, and someone will spot him during the commission. Or his gun will jam and the vic will ID him. Or one of us will get lucky and walk in on him in the act.’

‘What we are going to do,’ Quirk said, ‘is flood the next crime scene, try to seal it off, if it’s someplace where we can, in the hopes that maybe he hangs around to watch.’

‘Do you think he might?’ the mayor said.

‘FBI profilers think he might,’ Quirk said. ‘Our shrinks think he might.’

‘How will you know him?’

‘If he’s still carrying the murder weapon,’ Quirk said.

‘Jesus Christ,’ the mayor said. ‘You’re going to search everyone in sight?’

‘Everybody we seal inside the crime-scene area,’ Quirk said.

‘Men and women?’ the mayor said.

‘While we’re at it,’ Quirk said. ‘Why take a chance that the profilers are wrong.’

‘You’ll have some female officers there?’

‘We will.’

Even so,’ the mayor said, ‘the civil libertarians will go crazy.’