Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Independent Thinking Press

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

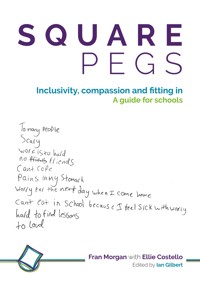

Over the last few years, changes in education have made it increasingly hard for those children who don't 'fit' the system - the square pegs. Budget cuts, the loss of support staff, an overly academic curriculum, problems in the special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) system and difficulties accessing mental health support have all compounded pre-existing problems with behaviour and attendance. The 'attendance = attainment' and zero-tolerance narrative is often at odds with the way schools want to work with their communities, and many school leaders don't know which approach to take. This book will be invaluable in guiding leaders and teaching staff through the most effective ways to address this challenge. It covers a broad spectrum of opportunity, from proven psychological approaches to technological innovations. It tests the boundaries of the current system in terms of curriculum, pedagogy and statutory Department for Education guidance. And it also presents a clear, legalese-free view of education, SEND and human rights law, where leaders have been given responsibility for its implementation but may not always fully understand the legal ramifications of their decisions or may be pressured into unlawful behaviour. Suitable for all professionals working in education and the related issues surrounding children and young people's mental health, as well as policymakers, academics and government ministers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 638

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Square Pegs

There is an old African saying: ‘Until the lions have their own historians, the tales of glory will always be written by the hunters.’ Fran Morgan has assembled here some lions and while they don’t write too many tales of glory – although there are some – they do make us all realise why so many square pegs unnecessarily gain so little from our schooling system. Twelve years ago, Michael Gove sent a King James bible to every school. The next secretary of state for education should send a copy of this book to every new head teacher and put it on the reading list for all initial teacher training courses.

Tim Brighouse, former Commissioner for London Schools

This is one of the most riveting books on education I have read in a long while. Its aim – to provide practical solutions for schools and families struggling with the increasing number of children who don’t thrive in our current system – could not be more timely. The array of richly qualified writers places compassion, purpose and student autonomy at the heart of best practice. Their approach would surely work not just for those who avoid school, but for those stuck within it. Square Pegs is a must-read for parents, governors, staff and students who’re up for a quiet classroom revolution.

Madeleine Holt, filmmaker and education campaigner

This is a book that is firmly on the side of children as they try to come to terms with a school system that is designed to encourage conformity. It highlights the way some schools manage to set the child at the heart of what they do in every sense of the term. There are case studies that shine a light on the child’s perspective and solutions offered for other schools to try. Reading it is both heart-wrenching and uplifting … but uplifting wins.

Mick Waters, Professor of Education, University of Wolverhampton

This book is steeped in the experience and expertise of families, teachers and leaders. It tells the story of a system that is fraught with unintended consequences, brings the lived experiences of young people alive and challenges the notion of one-size-fits-all strategies. The voice of school leaders and teachers, ambitious to see the young people in their care thrive, roar at us across the page. It’s a book of confidence for professionals and parents alike to rise above the distracting noise about attendance, exclusion and ‘what works’ narratives. A much-needed book ensuring the voice and experience of young people is heard and helping to inform what happens next.

It’s a must-read for everyone with a vision of an education system that can be ‘fixed’ through collaboration and brave actions.

Margaret Mulholland, Inclusion Specialist, Association of School and College Leaders

Our high-stakes, test- and exam-focused system is failing too many children. It literally fails those who struggle to attend school or are marked as failures in exams. It metaphorically fails those who attend and get their grades, but at a personal cost to themselves, their love of learning and their families. This will continue to be the case for as long as schools are judged in the main on test and exam results, placing the burden of whole-school success or failure on children’s shoulders.

For the good of every child and, indeed, of educators themselves (most of whom want to provide the best possible learning experiences and strive to do so in spite of our one-size-fits-all model for education), it’s time to listen to the canaries in the cages – the children who simply cannot cope, let alone thrive, within our restrictive, reductive system. Change made for those who suffer most will benefit the whole school community.

Alison Ali, More Than A Score campaigner and strategic communications expert

In recent years, many schools in England have started to implement strict policies around behaviour, curriculum and attendance. As the screws tighten, more and more square pegs (read ‘deeply distressed young people’) have started voting with their feet. When you stop going to school, it creates all kinds of problems: home visits, financial penalties and, incredibly, the threat of custodial sentences for the parents and carers of persistent ‘offenders’. The fact that so many young people should choose such strife over attending school should tell us something very important about their lived experience of our one-size-fits-all education system. It seems likely that increasing numbers of square pegs will continue voting with their feet until we reach crisis point. But this crisis can be averted if we listen to the voices of those affected now. This brilliantly curated book is an absolute must-read for anyone interested in creating a more diverse, empathic, responsive educational ecosystem that works for all young people.

Dr James Mannion, Director, Rethinking Education and co-author of Fear is the Mind Killer with Kate McAllister

No child should miss out on a good education and the chance of opportunities in life just because their school doesn’t give them the support they need to succeed. Most schools cherish and value the children who have special educational needs; there are also some who do not place inclusion high on their list of priorities, and exclude or marginalise children rather than provide the mental health and therapeutic support they need.

Recently, a 13-year-old girl with autism gave me a list of what a good school for her would look like: well organised, supportive, calm, focused on learning, there to help. These are all things we would want to see for every child in every school. After spending two years out of the classroom because a succession of schools was unable to meet her needs, she went on to find a school which understood her and provided the springboard she needed to do well. She went on to achieve great things in her GCSEs and is now in sixth form. Like Square Peg, I want all schools to see the potential in all children and provide the support they need.

We should all be grateful to Square Peg for all they do to advocate for children who need most help, and for showing how schools and parents can work together with children to provide a positive environment to learn. Every child deserves the best start in life, and positive outcomes for all children must be at the heart of a successful education system.

Anne Longfield, CBE, Chair of The Commission on Young Lives

In order for a society to become healthy, whole and progressive, it must be willing to listen to the square pegs that it has created within itself. It is when square pegs choose to be silent and when they choose to communicate that we must pay careful attention to, for the sake of all of us. Everyone who was gifted with a square peg in their life will tell you so. Square pegs are our compass and our orienteers: they are the first to notice when we lose our way, the first to see that we have crossed our own boundaries, and the first to feel when we single-mindedly keep digging one-shaped holes. This is why this book had to be written, and this is why it must be read by anyone who cares about the education system of this country.

I have been following Fran, Ellie and their many supporters, diligently collecting piece by piece of evidence for several years, to assemble the overly complicated puzzle of square pegs, to improve our society. The result is brutally honest, yet optimistic. It is visionary yet chooses a pragmatic approach and offers many quick wins. It offers a sensitive choice of a diverse set of writers, through which one thread of pearls is coming out very clearly: it is about compassion, consent, community and relationships. It is about holding our societal compass close to our hearts and struggling to keep it safe. This is the struggle of all of us – or at least it should be.

Dr Carmel Kent, lecturer at the Open University, educational researcher, author of AI for Learning and a parent with lived experience

Making schools more inclusive is essential to ensuring the wellbeing and ability to thrive of every young person. Creating a sense of belonging and using trauma-informed strategies to help the system welcome the square pegs, rather than continuing to force them into round holes, is clearly the way forward. The current government one-size-fits-all approach, particularly to SEND and behaviour, needs a rethink.

This book offers a wealth of practical examples of how collaboration between schools and families, alongside the will to make a culture shift, can lead to successful inclusion practices. It is very readable and contains practical advice and solutions, framed within the current educational context, that leaders, teachers and support staff can use to create the right systems and support to ensure that every child and young person really is more than just ‘fine in school’.

Judy Ellerby, Lead Policy Manager, SEND, Disabled Members, Behaviour, Exclusions, National Education Union

square peg or square peg in a round hole

informal: a person or thing that is a misfit, such as an employee in a job for which he or she is unsuited1

The trouble with square pegs is that by forcing them to fit the system’s round holes, you end up damaging the peg, not the hole.

1 See https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/square-peg.

FOREWORD BY SIR NORMAN LAMB

I have long been a supporter of Square Peg. I first became aware of their work in my time in Parliament and have been keenly following them ever since. The support they provide families facing challenges in education is of immense value, and they have given a voice to those children and young people who are experiencing persistent absenteeism, many of whom have mental health problems and unmet needs. Square Peg has also played a significant part in promoting the importance of an inclusive and supportive education system that works for all children and young people.

Education is a key pillar in children and young people’s lives as they grow and develop, and in particular, plays an important role in their mental health and wellbeing. It’s crucial in improving life chances, maintaining social connections, providing access to support and helping children learn how to look after their mental health.

Education should be inclusive of everyone no matter what a child’s needs and experiences may be, and this is a principle I have strongly endorsed throughout my career. However, the reality lies far away from this, and sadly the education system currently operates to celebrate uniformity rather than embracing diversity.

We have seen this most recently in the behaviour agenda, where the use of punitive approaches has become commonplace in responding to children and young people’s behaviour. I have been particularly horrified by the rise of school exclusions as a form of punishment, with data showing a steady increase in the use of both suspensions and permanent exclusions before the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Often, the children who face exclusion are the ones with the greatest need. Children communicate their distress through their behaviour, and challenging behaviour can often be the result of underlying conditions, unmet emotional needs, difficulties at home, at school or in the community, and exposure to trauma. We also know that the use of punitive approaches to behaviour can be harmful to children and young people’s mental health and actually has the potential to re-traumatise. The cost of exclusion both to the individual but also to society is incalculable. The loss of human potential is tragic.

We need to urgently move away from a system where we punish and exclude children and young people for their life experiences and needs, and instead move to a place of compassion and understanding. This means creating supportive and inclusive school environments for all children and young people to thrive and offering help to those who are struggling most.

It’s my strong belief that by seeking to understand children and young people and their needs in a more sophisticated and compassionate way, then learning can be iifacilitated. After all, happy, healthy children are better able to learn. At the heart of this should be prioritising whole-education and trauma-informed approaches to mental health and wellbeing in every setting across England. Such approaches are vital in helping to create a culture where every student is recognised and valued.

I am sure this book will be of great practical value to many school leaders, educators, practitioners and professionals, and I would like to thank Square Peg for all they do to advocate for those who need it most, including our education workforce.

Prologue

THE CANARIES IN THE MINE BY JO SYMES

What if our ‘square pegs’ aren’t the problem? What if they are actually the canaries in the mine, alerting us to the mounting problems in our education system?

In her book, Troublemakers: Lessons in Freedom from Young Children at School, Carla Shalaby (2017) discusses ‘animal sentinels’, animals which are purposefully used to provide advanced warning of disease, toxins and other environmental threats to humans. She explains that these species are selected based on their heightened susceptibility to particular hazards. They are often sacrificed to save us.

The most famous example is the canary, used in coal mines in the early 20th century to give advanced warning of deadly gases, such as carbon monoxide. Because these birds were small and had particularly sensitive respiratory systems, the poison killed them quickly, leaving the miners with enough time to get out and save themselves. What if, suggests the author, we saw our square pegs as such canaries?

The child who deviates, who refuses to behave like everybody else, may be telling us – loudly, visibly, and memorably – that the arrangements of our schools are harmful to human beings. Something toxic is in the air, and these children refuse to inhale it. It is dangerous to exclude these children and silence their warnings. (Shalaby, 2017: xxxiii)

Shalaby learned the canary metaphor from Thomas, a father of a 5-year-old boy who could not – and would not – comply with the behavioural expectations of his kindergarten teacher:

Though the child suffered a mood disorder, Thomas challenged the assumption that the disease made his son inherently broken or bad. Much like the canary’s fragile lungs, this child’s brain leaves him more susceptible to the harms of poison. He’s more sensitive to harm than the average child. Still, the problem is the poison – not the living thing struggling to survive despite breathing it. After all, in clean air, canaries breathe easily. (Shalaby, 2017: xxii–xxiii)iv

Look at our square pegs. Look at the list of children refusing to attend your school, with or without the knowledge/agreement/complicity/other of their parents.1 Look at those who are constantly in trouble when they do attend. Look at those who have been excluded, shamed, moved on. Look at those in your bottom sets, in your nurture rooms, in your ‘special classes’, in your conscience. What are they saying? What warning are they giving you? What will you do now you hear them?

References

Shalaby, C. (2017) Troublemakers: Lessons in Freedom from Young Children at School. New York: New Press.

1 This is discussed further in the Introduction. Am I complicit if I prioritise my child’s mental health and knowingly agree not to force her into school? The law says I am. What do you say?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Square Peg wouldn’t exist had it not been for my own square peg, my daughter, and Peter Kyle’s support which gave me the momentum I needed at the beginning. It wouldn’t exist now had it not been for Square Peg’s director, Ellie Costello, her two children and their journey through the special educational needs and disabilities, health, social care, children and adolescent mental health services, and education systems.

It also wouldn’t exist without Ian who proposed the idea of a book in the first place, and who supported us in pitching the concept to our publisher, Crown House. His wisdom and experience in the editing process – and with a growing number of contributors that was a mammoth task – allowed us to piece together a diverse range of views and writing styles. He has been an advocate of change in the education system for many years, and continues to support schools in this regard, alongside his many Independent Thinking associates.

In compiling this book, we ploughed our own Square Peg network and that of Ian’s Independent Thinking network. Several others submitted contributions which didn’t quite make it into this book, so our grateful thanks go to: Dr John D’Auria, Dick Bryant, Sophie Christophy, Ritam Ghandi, Ros Gowers, Sarah Harrison, Dr Rebecca Johnson, Dot Lepkowska and the team at Educate Ventures, Dr James Mannion, Andrew Morrish, Stephen Steinhaus, Lucy Stephens, Niamh Sweeney, Adele Tobias, Tom Varley and Aliyah York.

Our thanks also go to Eliza Fricker-Baines, another square peg parent, for her insightful illustrations which mark the start of each of the five parts of the book. You can see more of Eliza in her blog, Missing the Mark, and in her illustrated book, The Family Experience of PDA: An Illustrated Guide to Pathological Demand Avoidance (2021).

A final and most important word of thanks goes to the small but perfectly formed team at Crown House Publishing, who were not only prepared to invest in us, but who have been an amazing source of encouragement and support throughout.

This book represents the work and passions of so many wonderful people, and our heartfelt thanks go out to all of you.vi

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Dr Helen Andrews

Helen runs Family Matters in Warwickshire (www.familymattersinwarwickshire.co.uk), offering child clinical psychology services to children and their families in and around Warwickshire. Prior to this, she worked in child and adolescent mental health services for 15 years and convened on and taught the child and adolescent module on the University of Warwick’s master’s course in clinical applications of psychology.

Dr Chris Bagley

Chris is a psychologist working in Bristol and was formerly based in a youth offending team. He is director of research at the social enterprise States of Mind, co-director at Square Peg and a tutor at UCL’s Institute of Education. He has a keen interest in educational transformation and systems change. His academic work, media publications and other writing can be found at www.chrisbagley.co.uk.

Adele Bates

Adele has been a teacher for nearly 20 years, empowering educators to support pupils with behavioural needs and social, emotional and mental health needs. She is an international keynote speaker, a BBC Radio 4 expert on teenagers and behaviour, the author of ‘Miss, I don’t give a sh*t’: Engaging with Challenging Behaviour in Schools (2021), and an international researcher on behaviour and inclusion. For her tips and resources, check out www.adelebateseducation.co.uk.

Andrew ‘Bernie’ Bernard

Bernie started Innovative Enterprise (www.innovativeenterprise.co.uk) in 2006 to help those within organisations (including schools) to perform better. He has delivered more than 1,800 workshops and international talks to more than 165,000 young people, and is a TEDx speaker and entrepreneur. His book, The Ladder: Supporting Students Towards Successful Futures and Confident Career Choices, was published in February 2021.xiv

Adrian Bethune

Adrian runs Teachappy (www.teachappy.co.uk), which puts happiness and wellbeing at the heart of education. He is also an instrumental figure across several wellbeing organisations and initiatives, including as deputy chair of the strategic board of the Well Schools Movement.

Dr Beth Bodycote

Beth is the founder of Not Fine in School (www.notfineinschool.co.uk), which had a membership of nearly 30,000 in its closed Facebook group for parents by the end of July 2022. She is a parent with lived experience, and has recently completed a PhD on the parental journey when a child faces barriers to attendance.

Ginny Bootman

Ginny is an educator with over 25 years in education as a classroom practitioner, special educational needs coordinator and head teacher. She is passionate about all things SEND, has been published multiple times in the TES and is an associate of Undiscovered Country. She speaks nationally about promoting home–school links through an empathy-based approach. Find her at www.ginnybootman.com and @sencogirl on Twitter.

William Carter

William is a PhD student at the University of California, Berkeley and a Fulbright scholar with a first-class degree in politics from the University of Bristol. On top of studying for his doctorate in political geography, specialising in Atlantic history, William is a neurodiversity campaigner and spends much of his time engaged in high-level meetings, policy development and advocacy with university leaders. He has featured in profiles in The Times, i newspaper, on ITV’s This Morning and on Ian Wright’s Everyday People podcast.

Mike Charles

Mike is a senior director and chief executive officer at Sinclairslaw (www.sinclairslaw.co.uk), specialising in education law and human rights. He frequently appears on BBC Breakfast News and national radio, commenting on high-profile stories involving education and disability law.xv

Professor Luke Clements

Luke is the Cerebra professor of law and social justice at the School of Law, University of Leeds (www.lukeclements.co.uk). As a practising solicitor, he has conducted a number of cases before the European Commission and Court of Human Rights. His academic research, litigation experience and input to parliamentary bills focuses on the rights of people who experience social exclusion.

Dr Wendy Coetzee

With over 25 years in clinical practice, Wendy has developed a specialism for supporting children with attachment and developmental trauma, using dyadic developmental practice (DDP) and trauma-informed practice. She is an accredited DDP trainer, helping schools to develop trauma-informed practice using playfulness, acceptance, curiosity and empathy (PACE) to support vulnerable learners. Find her at www.thefoundationsconsultancy.co.uk.

Andrew Cowley

Andrew was formerly a primary school deputy head teacher and is now a wellbeing writer and speaker, co-founder of the Healthy Toolkit, and author of The Wellbeing Toolkit (2019) and The Wellbeing Curriculum (2021).

Dr Ian Cunningham

Ian chairs the governing body of Self Managed Learning College. He created Self Managed Learning in the late 1970s and is widely published on learning and education. His latest book is Developing Leaders for Real (2022). He has been a visiting professor in Hungary, India, the UK and the USA. Find SML College at www.smlcollege.org.uk.

Dr Andrew Curran

Andrew is a practising paediatric neurologist and neurobiologist who brings this knowledge to the education space. He has authored several books, including The Little Book of Big Stuff about the Brain (2008). He has presented on the BBC3 series Make My Body Younger and is an associate of Independent Thinking.

Natasha Devon, MBE

Natasha is a writer, broadcaster and activist, founder of the Mental Health Media Charter and involved in several other mental health organisations. She hosts a weekly xviradio show on LBC and writes regularly for national newspapers. She is a published author. Find her at www.natashadevon.com.

Professor Helen Dodd

Helen is a professor of child psychology at the University of Exeter Medical School. She has over 10 years of published research to her name, specialising in children’s play and mental health. She is funded by a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship.

Dr Simon Edwards

Simon is a founding member and CEO of Beyond the School Gates (www.beyondtheschoolgates.co.uk). He has been involved in youth and community work for over 34 years and lectures in youth studies at the University of Portsmouth. Beyond the School Gates emerged through his work at Portsmouth, and he now leads their mentor team and supports excluded young people and their parents as a mentor.

Richard Evea

Richard is chair and trustee of Beyond the School Gates (www.beyondtheschoolgates.co.uk). He spent 40 years in secondary education, with the final 20 years as a head teacher in two secondary schools in South East England.

Dr Naomi Fisher

Naomi is an independent clinical psychologist living in Hove and working as a therapist, speaker, trainer and author. Her book about self-directed education, Changing Our Minds, was published in February 2021. Find Naomi at www.naomifisher.co.uk, naomicfisher.substack.com and @naomicfisher on Twitter.

Karine George

Karine is an author, keynote speaker, education consultant and chief education advisor for Educate Ventures. She was a primary school head teacher for 25 years and speaks nationally and internationally on parental engagement, leadership and learning. She also co-founded Leadership Lemonade (www.leadership-lemonade.co.uk).

Rhia Gibbs

Rhia is the founding director and CEO of Black Teachers Connect (www.blackteachersconnect.co.uk) and a sixth-form sociology and criminology teacher. The organisation xviiseeks to build a community for Black teachers by supporting and promoting the recruitment and retention of Black teachers in the UK and worldwide.

Dr James Gillum

James is the principal education psychologist at Coventry City Council. He works with Square Peg to chair a research group of education psychologists from around the country, aiming to identify the most appropriate screening and interventions for extended non-attendance.

Dr Peter Gray

Peter is a research professor at Boston College, Massachusetts and a widely published author. His books include Free to Learn (2015) and Psychology (2010). He is a founding member of the non-profit organisations Alliance for Self-Directed Education and Let Grow. Read Peter’s posts in Psychology Today at https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/contributors/peter-gray-phd.

Stuart Guest

Stuart is the head teacher at Colebourne Primary School in Birmingham (www.colebourne.bham.sch.uk), a therapeutic parent and a trainer in attachment, adverse childhood experiences and trauma-responsive schools. With more than 15 years of experience as a head teacher, he writes and talks regularly on becoming a trauma-informed, attachment-aware school.

Dave Harris

Dave is an educational author with five books to his name, including Brave Heads (2013). He is also a speaker, consultant, Independent Thinking associate and part of the leadership team at Stone Soup Academy. He has 30 years of experience in all phases of education, including 12 in the role of head teacher.

Kerrie Henton

Kerrie is principal at Stone Soup Academy in Nottingham. She has worked in education since 1997 and in senior leadership since 2005. Find Stone Soup at www.stonesoupacademy.org.uk. xviii

Martin Illingworth

Martin has over 30 years of teaching experience and is currently a senior lecturer in education, leading the English and drama PGCE courses at Sheffield Hallam University. His book Forget School (2020) is the result of interviewing self-employed 20–30-year-olds about their experiences of school.

Nina Jackson

Nina is an author, Independent Thinking associate, mental health ambassador and creator of the Mind Medicine approach. She is also an award-winning motivational speaker. Her work as a mainstream and special educational needs and disabilities pedagogical and pastoral champion has bestowed her with the well-deserved title ‘Ninja’ Nina.

Sarah Johnson

Sarah has worked in pupil referral units and alternative provision for around 20 years, and is the president of the national organisation PRUsAP. She is a published author and regular speaker, and has been the Department for Education’s project manager for an alternative provision innovation fund project. Sarah is also a member of the Department for Education’s Alternative Provision Stakeholder group. Find her consultancy at www.phoenixgrouphq.com.

Dr Debra Kidd

Debra published her first book, Teaching: Notes from the Frontline in 2014. Since then there have been three more: Becoming Möbius (2015), Uncharted Territories (2018), co-authored with Hywel Roberts, and the latest, Curriculum of Hope (2019), which explores how a curriculum can be as rich in humanity as it is in knowledge. Debra is an Independent Thinking associate.

Lucie Lakin

Lucie is principal at Carr Manor Community School in Leeds (www.carrmanor.org.uk). She works closely with the executive principal, Simon Flowers.

Rt Hon. Sir Norman Lamb

Sir Norman Lamb served as the MP for North Norfolk and in various ministerial health roles between 2001 and 2019. He was awarded a knighthood in 2019 for his mental health campaigning. He is currently chair of three organisations working in xixthis field: Kooth (chair of the advisory board), the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition. In 2019, he also established a mental health and wellbeing fund in Norfolk.

Gina McCabe

Gina was a youth worker for many years and now runs Place Innovation, a specialist consultancy for a more socially just and environmentally sustainable world. Place Innovation has led Gina to start planning the Place Schools Trust, a free school concept in the making, which puts wellbeing at the heart of the curriculum and with a framework developed in partnership with the Innovation Unit.

Alasdair McCarrick

Alasdair has a background in youth and social work and currently lectures on the undergraduate youth studies and youth justice courses at Nottingham Trent University. He began teaching on the new BA in youthwork and MA in youth leadership courses in 2021/2022.

Dave McPartlin

Dave is the head teacher of Flakefleet Primary in Lancashire (www.flakefleet.lancs.sch.uk), which won Happiest Primary School and Primary School of the Year Runner Up at the National Happiness Awards in 2019. Its real claim to fame, though, was as a recipient of David Walliams’ golden buzzer at Britain’s Got Talent in 2019. Dave also presents on BBC Bitesize and Live Lessons.

Mary Meredith

Mary is assistant director of learning and skills at Hull City Council. She was a teacher, special educational needs coordinator and senior leader for 20 years prior to moving into a local authority role, initially at Lincolnshire County Council as a special educational needs and disabilities and inclusion lead. She advocates for trauma-informed approaches in schools. Find her at www.marymered.com.

Marijke Miles

Marijke is head teacher at Baycroft School (www.baycroftschool.com), a special school in Hampshire, and chair of the SEND sector council at the National Association of Head Teachers. She has more than 15 years of experience as a head teacher and has written for the TES and Huffington Post. She has a wealth of xxexperience supporting children with special educational needs and disabilities, particularly those in local authority care.

Professor Georgina Newton

Georgina is an associate professor of education at the University of Warwick. Her research focuses on teacher wellbeing and agency.

Edward Pearson

Edward has been a paramedic on the front line for 23 years. His experience in dealing with 999 calls involving children and young people has taught him the importance of putting parent voice front and centre.

Lorraine Petersen, OBE

Lorraine is an education consultant and special educational needs and disabilities specialist based in Worcestershire. She has 25 years of experience in the mainstream school environment as a teacher and head teacher, and was CEO of the National Association for Special Educational Needs for nine years. Find her at www.lpec.org.uk.

Dr Jane Pickthall, MBE

Jane is a virtual school head who promotes the education of looked-after children in North Tyneside. She is a trauma and attachment expert, and was awarded an MBE in the New Year Honours list in 2021.

Dr Maddi Popoola

Maddi works for Nottingham City Council and is keen to collaborate with other services to ensure that educational psychologists are key contributors to national government policy through quality evaluation and research. She co-authored a report in 2021 with Dr Sarah Sivers and the Pupil Views Collaborative Group on young people’s experience of education in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tom Quilter

Tom is senior development officer for the Information, Advice and Support Services Network at the Council for Disabled Children (CDC – www.councilfordisabledchildren.org.uk). He studied social policy and held a variety of roles within both local authorities and the charity sector prior to joining the CDC.xxi

Professor Kathryn Riley

Kathryn is professor of urban education at the Institute of Education, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society and co-founder of the Art of Possibilities (www.theartofpossibilities.org.uk). She is an international scholar whose work bridges policy and practice. International work includes two years heading the World Bank’s Effective Schools and Teachers Group. She has taught in inner-city schools, held political office in London as an elected member of the Inner London Education Authority and been a local authority chief officer. Her work on belonging is widely published.

Dan Rosenberg

Dan is a partner at Simpson Millar (www.simpsonmillar.co.uk), specialising in education and public law. Qualified since 2004, he works across a wide range of areas in education law and community care, with a particular interest in children and young people.

Alison Sauer

Alison is the chair for the Centre for Personalised Education (www.personalisededucationnow.org.uk), runs the Sauer Consultancy and is a regular contributor to government consultations on elective home education. She is widely regarded as an expert on flexischooling.

Nick Shackleton-Jones

Nick is the founder and CEO of Shackleton Consulting (www.shackleton-consulting.com), following on from more than 10 years as director of learning at BP, PA Consulting and, more recently, Deloitte. He is the author of How People Learn: Designing Education and Training that Works to Improve Performance (2019) and a regular public speaker.

Dr Sarah Sivers

Sarah is a child, community and educational psychologist. Along with Dr Maddi Popoola, she co-authored a report in 2021 on young people’s experience of education in the context of COVID-19. She also set up the Education Psychology (EP) Reach-Out webinar series during the pandemic to support education psychologists. Find EP Reach-Out at https://www.youtube.com/c/EducationalPsychologyReachOut/featured.xxii

Andy Sprakes

Andy is co-founder and chief academic officer of XP School in Doncaster, which was set up following the principles of High Tech High and Expeditionary Learning schools in the United States. He was previously head teacher of Campsmount Academy for eight years and deputy head for four years prior to that. Find XP Trust at www.xptrust.org.

Dr Bo Stjerne Thomsen

Bo is vice president and chair of Learning Through Play at the LEGO Foundation (www.learningthroughplay.com) and a visiting scholar at Harvard University. He spent nine years building the research agenda, network and organisational expertise on children’s development, play and learning in order for the LEGO Foundation to become a leading authority on learning through play.

Trevor Sutcliffe

Trevor is a co-founder of Challenging Education (www.challengingeducation.co.uk), providing education consultancy, training and monitoring to maintained and academy schools across all phases. The main body of Trevor’s work is in supporting schools and organisations to improve the life chances of children who are ‘disadvantaged’ or in receipt of free school meals.

Jo Symes

Jo created www.progressiveeducation.org as a resource for those exploring alternatives to conventional methods in education. This inspiration hub showcases innovations both inside and outside of the mainstream. Mainstream schooling was unsuitable for her children and she deregistered them in 2018. You can join the conversation and connect with thousands of others on a similar journey in the Progressive Education Group on Facebook.

Dave Whitaker

As a former executive principal of a number of special schools, alternative provisions and pupil referral units, Dave is now director of learning for Wellspring Academy Trust (www.wellspringacademytrust.co.uk), with its 28 schools across Yorkshire and Lincolnshire. He is an Independent Thinking associate. His first book, The Kindness Principle, was published in 2021.

Introduction

MY DAUGHTER IS A SQUARE PEG

I founded Square Peg to try to effect change in a system which is failing an increasing number of children. They are not just the special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) children. And they are not just the ‘challenging’ ones who end up in isolation or excluded. Many young people have developed excellent coping mechanisms to get through each day, and with budgets stretched and an ever more dictatorial curriculum, they often pass unnoticed by teaching staff who are just trying to survive.

This book is for those in education who want to do the right thing by their square pegs, but are constrained by (often counterproductive) government and local authority directives. We know it is possible to forge a different path within the current system, and we have contributions from schools which are doing just that. This book was compiled to provide creative, inspirational and pragmatic advice, so that those in the mainstream sector are better able to support their square pegs; supporting the supporters, if you like.

My story – the beginning of this book’s journey – is one of many; all unique but with common elements and similar, often catastrophic, end results.

It was after a particularly traumatic summer that my 8-year-old daughter missed nearly a year of primary school. Later on, she missed most of secondary school. Why? That’s simple: she couldn’t do it.

Let me repeat that: she simply couldn’t do it. Not wouldn’t, but couldn’t.

You may know this as ‘school refusal’, but I would like you to erase that phrase and reframe it in terms of barriers to attendance instead. She was not refusing to go to school. She just couldn’t. Initially, her particular barrier was not trusting that I was safe when she was at school. Later, on moving to secondary school, she didn’t trust the adults who were tasked with keeping her safe. She also couldn’t see the point of a lot of what she was being taught or the way in which it was being taught. She is a great judge of character and, to be fair, she was often on the money. The secondary school prioritised its position in the league tables above all else, and made it clear that children should be seen and not heard. Her strength of character was her undoing in a system that allows – even encourages – such an approach from schools. Ironically, that same strength of character which meant that she didn’t fit the system will most likely be her springboard to an extremely successful future.2

Many children ‘mask’ in school by pretending they are fine. I know my daughter did. They desperately want to be there and fit in along with everyone else, but attending is a daily struggle – one that eventually breaks them. Persistent absentees (a Department for Education label for those whose attendance drops to 90% or less) are a real problem for schools because they lower attendance figures, with the threat of a potential downgrading by Ofsted if average attendance is deemed inadequate. I have heard of head teachers whose performance reviews include an attendance key performance indicator, with personal consequences for missing the target. For parents, absenteeism brings with it the threat of fines and prosecution if a child’s attendance falls below a magic threshold (increasingly upwards of 95%). Yet ‘chronic’ or ‘persistent’ absence is a global problem, widely recognised to be multifaceted and complex, and only made worse by threats and sanctions. It’s a problem with no quick fix in an education system where one-size-fits-all is sadly both convenient and cost-effective (in the short term).

Like many parents in the same position, our journey was a roller coaster. At times it was horrendous; at others we were lifted up by wonderful individuals – ‘champions’ who changed our trajectory. And that is really the message of this book: that, despite a system which frequently causes damage and exacerbates problems, it is within the gift of governors, school leaders, senior leadership teams and individual teaching staff to rewrite that narrative and make a huge difference to the lives of square pegs and their families. And all the children who struggle in different ways and for many and varied reasons are just that – square pegs in a system of round holes. They are often made to fit the system rather than the system being made flexible enough to meet their needs.

The first step to addressing a problem such as this is recognising that it’s a problem and not just a few wayward children with lenient parents. I’m sharing our story here, but we are far from alone. Before we go any further, I want to share with you the messages we have received from just a few other square pegs – their pleas to schools and expressions of what it has felt like for them to be forced to do something they simply cannot do. Please read these and remember them; these children and their families are the driving force behind this book.3

C, age 11

Z, age 134

M, age 9

H, age 85

S, age 10

O, age 126

F, age 127

F, age 128

I, age 149

L, age 1311

B, age 1112

B, age 1713

A, age 11

There are common threads in these words – 14of not fitting in, being understood, or valued. Of a lack of flexibility, ‘solutions’ chosen by adults that don’t work for the children they are designed to support, of children trying to be heard and their words falling on deaf ears. And of parental concerns being disregarded (see Chapter 8: ‘Lessons from a 999 call’). No child should feel like this on a daily basis, with no way out. And for those who may still think it’s just a few wayward children, let’s see what the data has to say. Since exclusion receives a lot of attention, we will start with the most recent pre-pandemic data on suspensions and exclusions (on the basis that the pandemic skewed much of this data).1

In 2019/2020, there were 5,057 permanently excluded pupils in England, with 154,524 receiving a suspension or fixed-period exclusion (FPE). However, only 61,608 received more than one FPE and only 156 were ‘repeat offenders’ with 20 or more FPEs.2 We know that there is a well-trodden path from exclusion to youth justice (Arnez and Condry, 2021), and that the numbers have been growing steadily. Of course, behaviour that puts the safety of the child, their peers or staff at risk needs to be addressed, and behaviour that disrupts the class must be managed. All of this has led to exclusion being in the spotlight, with commensurate attention, investment and resources. The controversial debate in education is how this sort of behaviour should be managed, with advocates of zero tolerance focusing on disciplinarian behavioural approaches and advocates of trauma-informed, attachment-aware neuroscience seeing behaviour as a means of communication and focusing on relationships and compassion.

Now let’s look at persistent absence. For the 2018/2019 academic year, there were 771,863 persistent absentees, rising to 921,927 in the autumn term of 2019. That is more than nine times as many pupils as those who have received more than one suspension, yet absence receives little attention bar the standard ‘attendance equals attainment/bums on seats’ narrative. In the autumn term of 2019, 60,247 pupils missed 50% or more of the academic year, up from 39,250 three years previously.3 These are huge numbers compared to exclusions, yet until COVID-19 arrived they sat completely under the radar. More recent numbers probably disguised a continuing growth in persistent absence within discounted COVID absences, and we may not be able to accurately separate the impact of the pandemic for some time.

What is also astonishing is that for approximately 40% of ‘persistent’ absences,4 there is no formally recorded reason (usually coded O for ‘other’ unauthorised absence, C for 15‘other’ authorised absence, N for no reason yet or I for illness).5 In contrast, for exclusions, there are no less than 11 reasons, ranging from theft to physical assault against an adult (Department for Education, 2017: 17) and only 17–18% are classified as ‘other’6 (with a proposal that the ‘other’ category now be removed). ‘Attendance equals attainment.’‘It’s vital for safeguarding.’‘One day missed is one grade dropped.’ We hear these messages constantly, but how can we know what support to put in place or what interventions might help if we don’t understand the underlying problem?

The really dangerous consequence of a lack of accurate data is the assumptions that are made. To illustrate this point, let me share two conversations about the total number of persistent absentees. One was with an ex-deputy head teacher who simply believed that 90% of these pupils were disengaged from education. In other words, they were just truanting. The other was a psychiatrist who stated that, in her professional opinion (and she sees non-attenders on a daily basis), 80% of these pupils had an anxiety-related issue which impacted directly or indirectly on their ability to attend school. That is a discrepancy of hundreds of thousands of children. We cannot simply make assumptions about the truth, when the only truth is that we don’t know why these children are absent. There is also a conflated argument, reinforced through teacher training, that because excluded children often have a history of persistent absence, persistent absentees are therefore more likely to exhibit antisocial behaviour or end up in prison. That is just another unfounded and dangerous assumption.

Despite claims to the contrary, we have an education system that has been starved of cash, that is coerced into valuing academic attainment above all else, that has a process for identifying and supporting children with SEND which is great on paper but failing miserably in practice (House of Commons Education Committee, 2019), and it’s generally accepted that our child and adolescent mental health services are hugely overstretched and failing to meet need (Crenna-Jennings and Hutchinson, 2020). On top of that, the UK has some of the least happy children in the world (Children’s Society, 2021), who are arguably under more pressure than any prior generation and facing a future that doesn’t look too appealing (think climate change, the economy, Brexit-related issues, COVID-19 and its ongoing fallout, a cost of living crisis). Of course, the square pegs have always been there, and in increasing numbers in recent years, but the pandemic has shone a stark light on the disadvantages that many children and young people face.

If the data doesn’t tell us what is behind issues like non-attendance (and, remember, this is just one aspect of what makes a square peg), what do we know? Although anxiety can so often be the trigger that leads to persistent absence, as was the case with my daughter, underlying causes are many and varied. 16

We do know that in terms of pupil characteristics, the square pegs (or at least those who appear in the official absence and exclusions statistics) are all the usual suspects: pupils on free school meals, who account for 32% of all persistent absentees, and those with SEND (25%) – mainly children on SEN support, but also 25% of all children with an education health and care plan (EHCP).7 Those from ethnic minorities and with English as an alternative language feature too, but to a lesser extent. Many square pegs will have social, emotional or mental health (SEMH) issues, which covers a vast array of need and could apply to any of us at some point in our lives. Yet even with – or despite – these acronyms, we are still missing the nuances involved.

Take SEND. There are children with undiagnosed SEND and there are those who have been diagnosed but remain unsupported. Indeed, the term SEND covers a massive range of need, from complex physical disabilities to underlying health conditions (including SEMH), which create secondary needs with debilitating anxiety and mental health issues. It spans those with EHCPs and the much larger numbers on SEN support, not to mention the intersectionality issues that arise when we cross-reference these challenges with factors such as gender, sexuality, social background and ethnicity. Put simply, for many children and for many reasons, the mainstream school environment is just too much.

Some square pegs – whether they go to school or not – will have experienced bullying. Some, perhaps many, will have experienced trauma, and we touch on this in more detail later, particularly in Part IV. Some will have chronic health conditions which constitute a SEND issue or simply require some ongoing process of adjustment to the norm. Then there are those children whose needs are fuelled by circumstances at home or in their local community, which not only make school a low priority but create behaviours deemed unacceptable by the system (from being there and causing problems to causing problems by not being there). Some will struggle to fit temporarily; for others it’s a more permanent state of affairs.

So, what can we do when faced with such a vast and diverse range of underlying needs? My experience suggests that the only way school leaders can respond effectively is to build trust, invest in relationships and collaborate with families in order to help create the right culture and environment which allows them to meet each child’s needs. It starts with ensuring that those needs are accurately and comprehensively identified, in order to agree the support (in its widest sense) that is necessary for the child to utilise the education system and carve out their own best path. Securing that support can be another mountain to climb, but if the trust and relationships are strong there will be things that can be done to help along the way. 17

All of this starts with genuine, empathetic listening (often referred to as ‘active listening’). That means listening (and really hearing) the square pegs and their advocates – in most cases, their parents. Square pegs are the canaries in the mine, telling us that there is a palpable tension between an education system driven by efficiencies of scale, top-down control, data and results, and trying to educate children who are, like the rest of us, confoundingly and beautifully unique. If we do not show ourselves as willing to listen, we leave children, especially younger children, with two main routes for expressing their emotions: they act out or they shut down. Those who act out and exhibit ‘challenging’ behaviour often find themselves sanctioned and even excluded. Those who shut down and withdraw may remain under the radar, going unnoticed behind masked struggles for the entirety of their school career. Others may survive in that mode until their coping strategy fails, their attendance plummets and they become one of those pesky ‘school refusers’.

My daughter was a case in point. We never really got to the bottom of her unmet needs (too often the system is just looking for a diagnosis box to tick). In primary school, things improved, although not through the children and adolescent mental health services support we received, which was potentially counterproductive, but through a member of the school’s senior leadership asking a simple question in a staff meeting: was there a teaching assistant prepared to work with us? That led to our first ‘champion’ (and square pegs and their families need all the champions they can find). Mrs B earned our trust and gave both me and my daughter the supportive relationship we so badly needed. It took many months, and was only possible because she was committed to helping us and really believed that she was ‘the one’ who could help my daughter to return to school. She was the right person; it wouldn’t have worked with Mrs C who had spare capacity, or Mrs D whose job it was to support all the square pegs. Genuine relationships are the only ones that genuinely count. They allow support to be tailored to specific needs and delivered under an umbrella of trust.

It’s also worth noting that blanket interventions don’t work. Many of the standard strategies (arriving a little late or leaving a little early, a ‘get-out-of-class’ card, building up a part-time timetable and so on) work some of the time for some square pegs but their effectiveness is limited (Not Fine in School, 2020). Just as adults don’t ‘mend’ or perform after a standard offer of therapy, so the speed with which a square peg can heal, and the support they need at any point in time, will vary hugely.

We were lucky in other ways too. We were never actually fined or prosecuted, although my daughter was told on several occasions that we would go to prison if she didn’t go to school (please note: this doesn’t work). One of the huge frustrations with persistent absence (or school ‘refusal’ as it remains stubbornly known across much of academia) is the judgement of whether parents are knowingly allowing their child to be absent, as this then makes them complicit. Knowledge, agreement and complicity all (obviously) have different meanings and their use will be extremely sensitive, loaded 18and triggering to those whose children have struggled to attend. It’s tied up in the legal stuff too – parental responsibility and the lack of recognition that it’s not refusal.

It’s also tied up in some of the research in which academics have pigeonholed school ‘refusers’ according to whether the absence is with their parents’ knowledge and/or complicity. If my daughter had been ‘acting out’ and received a FPE instead, the same argument would apply, except that it wouldn’t be a criminal offence. If she was ‘truanting’ (another word we don’t use), I may have known or not known, understood or been complicit. But if it was a result of her needs not being met at school, then we would still have remained unsupported and potentially been fined or prosecuted. I would probably have had little agency over any of these scenarios other than trying to advocate on her behalf. Of course, I could have not cared, but this may have been because the system also failed me, so why would I expect anything different for my own children?

Back to our champions. Later, in secondary school (our second), we were gifted a deputy head teacher who believed that his school was there to serve his local community, whatever that looked like. Mr A took my daughter on roll, and she ‘did’ secondary school without ever setting foot on site. A Statement of Educational Needs meant that we could pay for a tutor (other-worldly and with buckets of wisdom, but that’s another story), and we had a fortnightly exchange of work with the school. He registered our home as an exam centre, even sending invigilators so she could take her GCSEs. That gave my daughter the results she needed to go to a mainstream sixth-form college, and, combined with her jaw-dropping strength of character, she never looked back. Without Mr A that wouldn’t have been possible. His school and the first secondary school in my daughter’s story are less than two miles apart, but a whole cosmos separates their ethos and culture.

All of this requires time, flexibility and resources, but, even before that, it needs senior leaders to step in and protect families from the rigidity and inflexibility of the system. They must create a culture and environment that can scaffold each child and collaborate beyond the school walls to find innovative and creative solutions. They must bend the rules where necessary and use all the resources they have within their school and community networks (and some) to make it work. That is what this book is about.

By the way, my daughter has now completed a degree in criminology. She never fitted in and went through hell as a result; we weren’t far behind. She will be a success despite the system, and I am all the more proud of her because of it. So, here’s to all the square pegs out there. Because those that don’t fit the system teach us the really important stuff in life – and we need to listen.19

References

Arnez, J. and Condry, R. (2021) Criminological Perspectives on School Exclusion and Youth Offending, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties, 26(1): 87–100.

Children’s Society (2021) The Good Childhood Report 2021. Available at: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/information/professionals/resources/good-childhood-report-2021.

Crenna-Jennings, W. and Hutchinson, J. (2020) Access to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services in 2019. London: Education Policy Institute. Available at: https://epi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Access-to-CAMHS-in-2019_EPI.pdf.

Department for Education (2017) A Guide to Exclusion Statistics (September). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/642577/Guide-to-exclusion-statistics-05092017.pdf.

Department for Education (2020) Pupil Absence in Schools in England: 2018 to 2019 (26 March). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/pupil-absence-in-schools-in-england-2018-to-2019.

House of Commons Education Committee (2019) Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. FirstReport of Session 2019. HC 20. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmeduc/20/20.pdf.

Not Fine in School (2020) School Attendance Difficulties: Parent Survey Results (March). Available at: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/a41082e1-5561-438b-a6a2-16176f7570e9/NFIS_Parent_Survey_Results_March_2020.pdf.20

1 We have consciously used pre-pandemic data throughout this book, for the reason cited above.

2 For data on permanent exclusions and suspensions in England for the academic year 2019/2020 see https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/permanent-and-fixed-period-exclusions-in-england.

3 For data on pupil absence in schools in England for the academic year 2018/2019 see https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/pupil-absence-in-schools-in-england-2018-to-2019.

4 For average data on pupil absence in schools in England across recent years see https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/statistics-pupil-absence.

5 See https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/pupil-absence-in-schools-in-england-2018-to-2019.

6 See https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/permanent-and-fixed-period-exclusions-in-england.

7 See https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/pupil-absence-in-schools-in-england-2018-to-2019 and https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/permanent-exclusions-and-suspensions-in-england-2019-to-2020.