8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

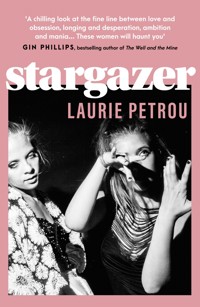

** SELECTED AS ONE OF COSMOPOLITAN'S HOTTEST NEW BEACH READS FOR SUMMER 2022 **

It's a fine line between admiration and envy.

Diana Martin has lived her life in the shadow of her sadistic older brother. She quietly watches the family next door, enthralled by celebrity fashion designer Marianne Taylor and her feted daughter, Aurelle.

She wishes she were a 'Taylor girl'.

By the summer of 1995, the two girls are at university together, bonded by a mutual desire to escape their wealthy families and personal tragedies and forge new identities.

They are closer than lovers, intoxicated by their own bond, falling into the hedonistic seduction of the woods and the water at a remote university that is more summer camp than campus.

But when burgeoning artist Diana has a chance at fame, cracks start to appear in their friendship. To what lengths is Diana willing to go to secure her own stardom?

The lines between love, envy and obsession blur in Laurie Petrou's utterly enthralling, unceasingly tense new novel. A darkly compelling coming-of-age story, perfect for fans of Donna Tartt's The Secret History or Liane Moriarty's Big Little Lies.

'A dark and dreamlike journey into the obsession, envy and love between two young friends in the 90s. The tension simmers in this atmospheric lake-side setting until the crushing end. Laurie Petrou's writing is melodic and immersive. A delicious read!' - Ashley Audrain, New York Times bestselling author of The Push

'A lyrical, nuanced deep dive into female friendship and all of its messy complexities. Laurie Petrou writes with a sharp observational eye and lush, gorgeous prose. Stargazer is an emotional masterpiece, both gritty and incandescent at once' - Laurie Elizabeth Flynn, bestselling author of The Girls Are All So Nice

'Tense is an understatement when it comes to describing Stargazer. Dark, but written with elegance, Stargazer will have you hooked' - Living North Magazine

'Stargazer entwines obsession, adulation and chilling female friendship into an enthralling, addictive read. Giving off strong The Secret History vibes, it drew me in from the first pages, and it'll make you want to be a 'Taylor girl', even though you know it's not a good idea...' - Lisa Hall, bestselling author of Between You and Me

'A chilling look at the fine line between love and obsession, longing and desperation, ambition and mania... These women will haunt you' - Gin Phillips, bestselling author of The Well and the Mine

'An outstanding book with some of the most beautiful lines I've ever read' - Samantha M Bailey, bestselling author of Woman on the Edge

'Stargazer is a galaxy of a novel: At once a story of friendship, a coming of age, and a dark and utterly captivating tale of family, lust, loss, fame, art and the ever competing hope and destructiveness of youth' - Amy Stuart, bestselling author of Still Mine

'A sinuous, captivating exploration of the mysterious depths of female friendship that had me hooked from its first pages... This unforgettable novel from a truly talented novelist is perfect for fans of Celeste Ng' - Marissa Stapley, bestselling author of The Last Resort

'A slow-burn literary thriller in the best possible way: eerie, beautiful, and impossible to put down. I loved it' - Robyn Harding, bestselling author of The Perfect Family

'Readers who loved Elena Ferrante's My Brilliant Friend will love Stargazer, a haunting tale of female friendship that explores the delicate and dangerous territory - in art and in love - that lies between inspiration and exploitation' - Heather Young, author of The Lost Girls

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 393

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Praise for Stargazer

‘A chilling look at the fine line between love and obsession, longing and desperation, ambition and mania... These women will haunt you’ – Gin Phillips, bestselling author of The Well and the Mine

‘An outstanding book with some of the most beautiful lines I’ve ever read’ – Samantha M Bailey, bestselling author of Woman on the Edge

‘Stargazer is a galaxy of a novel: At once a story of friendship, a coming of age, and a dark and utterly captivating tale of family, lust, loss, fame, art and the ever competing hope and destructiveness of youth’ – Amy Stuart, bestselling author of Still Mine

‘A sinuous, captivating exploration of the mysterious depths of female friendship that had me hooked from its first pages... This unforgettable novel from a truly talented novelist is perfect for fans of Celeste Ng’ – Marissa Stapley, bestselling author of The Last Resort

‘A slow-burn literary thriller in the best possible way: eerie, beautiful, and impossible to put down. I loved it’ – Robyn Harding, bestselling author of The Perfect Family

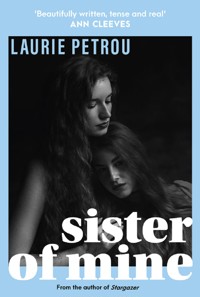

Praise for Sister of Mine

‘Beautifully written, tense and real’ – Ann Cleeves, writer of the Vera Stanhope novels

‘A solid psychological study of the relationship between siblings […] the tension arises as much from the careful peeling away of the two girls’ characters as it does from the mystery itself’ – Daily Mail

‘Steeped in intrigue and suspense, Sister of Mine is a powerhouse debut; a sharp, disquieting thriller written in stunning, elegant prose with a devastating twist’ – NB Magazine

‘Imaginative, beautifully observed characterisation. Masterfully written and enchanting, with more than a hint of menace’ – Caro Ramsay

‘Riveting debut’ – Publisher’s Weekly

‘Gripping, twisty, and singular. A not to be missed, well-worth-it read. Here’s hoping for more from this imaginative, insightful author’ – New York Journal of Books

‘An unputdownable page-turner’ – USA Today

‘One of the best novels I’ve read this year. A brilliantly conceived narrative with wonderful characters and great depth’ – Globe and Mail

‘A twisty, claustrophobic nail-biter’ – Entertainment Weekly

For Kristen

PART I

1

Rocky Barrens University, 1995. Freshman week: a welcome rave organized by upper-year art students in the middle of the night, in the middle of the woods. The swell of bodies moved like one thing, their feet pounding on the wooden floor of the Art Den. Techno and electronic music pulsed, lights sparkling like confetti that wouldn’t land, swirling around them, on them, in them. Girls tossed manes of hair, sweat slicking long strands to foreheads, glow sticks shining brightly, green and red and pink trails. The beat speeding up, the DJ bouncing frantically, ecstatically, the crowd jumping, eyes closed, reaching a fever, a fever, a fever, and then, so fast they couldn’t keep up, their hearts pumping wildly, it turned, it changed, it kept going. It was wild, and they were, too. The heat, the dance, the energy, the place. Oh, that place. Eventually, she would catch them all, freeze them into permanence as background characters. They’re famous now. And they came from here. How could anyone forget?

But, for now, Diana stood with her back to the wall, a small sketchbook and pencil in hand. She was trying for some respite from the heat, cigarette in her mouth, eyes blinking against the pulsing lights. Around the room, against the walls, dozens of people, slumped together, stoned, making out, holding one another in ecstasy, in Ecstasy, a feeling and a drug, a mood of tenderness and wonder and innocence, rising with the temperature. She watched the crowd, the shapes of bodies, the expressions on faces, the feeling, fabric clinging to skin. The clothes, of course, she knew and recognized: so many Marianne Taylor designs on the dancefloor. The Rave Queen. Diana didn’t go for rave or techno wear, even Marianne’s, in spite of her adoration of the woman who featured so largely in her life, the woman who had stood in this very room as a student herself all those years ago. Diana opted instead for a boxy shirt dress. She knew it was flattering, that straight things hung nicely on long bodies, long legs. She had learned how to dress for her extreme height. She had taught herself how to stand, how to act, how to be. To make the most of who she was.

More, even. She never slouched. She always held her chin up. She didn’t fidget. She molded what one journalist later described as an exacting personality. She taught herself to be decisive, noting that a firm yes or no when asked for her opinion made her appear expert, purposeful, unwavering, and that this commitment to a side, even if she didn’t really mean it or know she felt it the moment before she said it, cloaked any self-doubt she had and evoked perceptible admiration in people almost immediately. Their eyes would widen slightly, pupils dilating a fraction in concentration, belief. Sometimes, she followed a determined assertion up with a reason. No, you should do this instead. Yes, and don’t add anything. People liked to be told what to do, to trust someone who was sure. And, more than anything, after years of hesitation, Diana was sure.

Even now, with the drugs taking her mind on a trip, pulling her away, she held a part of herself close and firm and grounded. She bent her right leg up, her foot finding the wall, resting her wrist on her knee. She looked into the packed room, searching, and found her: her girl. Aurelle, speaking closely with another girl, smiling widely, animatedly, her characteristic red lipstick mostly faded except at the edges. And like magic, their bond manifested: she looked over, across everyone, and saw Diana. She raised her arm and waved happily; Diana lifted her own hand in response, then bent her head and began a small sketch of the scene. Aurelle, her head tipped back in laughter.

Eventually, the early dawn brought a weak light through the open doors and windows, and Diana collected Aurelle and they left the rave, walking out of the Den and into the woods like they were disembarking a spacecraft. Music followed them and it was hard to tell if it was an echo or if it was in their minds, their fading high. They talked about this a bit, marveling at the way their ears rang against the silence of the morning. The conversation bounced around as their bodies hummed while coming down, while their fatigue and slowly dawning sobriety made their tongues thick and their heads tender. Diana wrapped her fingers around Aurelle’s small hand and squeezed. A surge of joy seemed to bubble up inside each of them, encapsulate them, and they shared it, reveled in it like they were standing inside of something special, protected from the world. Best friends. Like sisters. They looked at one another and grinned. What could be better than this, than being here together? Diana breathed deeply, taking in the smell of the pines, and laughed. Aurelle did, too, knowing how Diana felt, that trust and love they had for each other, the comfort of relaxing into the other’s presence like a kind of melting, like a liquid filling up the same space.

‘I met this really cool girl. She’s from New York. Her dad collects old pinball machines,’ Aurelle said dreamily, swinging their hands between them.

‘I loved the remix of that old Carly Simon song,’ Diana said, remembering how the DJ had cut into the opening; ‘Nobody Does It Better’ with a fast, pounding beat.

‘I’m really thirsty,’ Aurelle said suddenly, her eyes wide.

‘Here. I saved a water bottle for you.’

‘Oh, God, thank you!’ She took the bottle, tipping the water greedily down her throat, wiping her mouth gratefully. ‘Thank you! Oh, look! How pretty.’

They had reached the lake, and the sun was coming up on the other side. A loon skittered across the surface of the water; Diana smiled and pointed to it even though Aurelle was already looking. They gazed, marveling at their luck, being here, now.

They went to work getting the canoe from its usual spot tucked away in the trees, laughing as it bobbed about and rocked while they got in. Aurelle scraped her shin on the side, as she often did, and swore, hitting the canoe in frustration. They heard other students around by the large campus dock and, looking through the trees, the girls saw that they were all jumping into the cold water in their sweaty clothes, hollering like children. Diana thought of the PJ Harvey song with the whispered line about little fish and wondered if it had been part of the music set that now was scattered like debris in her mind as the drugs wore off, tiny beats, or if it had arrived unbidden because of what she saw.

As they launched the canoe out of the trees on the shore, they waved to the ravers, now clamoring out of the cold lake, screaming and laughing, running back towards their cabins, to their warm rooms, to their beds, where they would sleep off the night into the day. Do it all over again.

2

Toronto, 1990. Diana was thirteen and sitting in a sturdy, wooden chair by a small, octagonal window in her top-floor bedroom of her family’s Toronto home, looking out. Her arm had healed enough that her doctor had removed the cast the day before. When he did, sawing through the plaster mold that had accompanied her throughout the summer, she was struck by the sight and smell of her arm: shriveled and pale, damp and weak, reeking of something close to decay. She stared at it, and the doctor had chuckled, not unkindly, suggesting that it would take some getting used to, but that with enough sunshine and play, it’d be good as new. She’d cradled it in her other arm as she got up to leave the hospital room with her mother, and the doctor had said, ‘Try not to do that, Diana.’ She looked at him, questioning. ‘Don’t coddle it. It’s stronger than it looks.’

She thought of that now and looked down at her arm, white and clammy like some deep-sea creature, resting in her lap. She flexed it, straightening it. Sunshine and play. She returned to her familiar viewpoint out the window. She had kept the chair in this position, at this angle, all summer. Turned just so, so she could see more. Looking out, looking in.

She had taken to drawing what she saw from her window and, after all of these weeks in her cast, banished from summer activities, from the lake and sports, her antique wooden desk was scattered with pencil studies. She glanced at them, feeling a thin pride at how her skill had improved over the weeks. She was nothing if not disciplined, and was pleased by results that came from practicing a thing. On her lap now was her sketchbook; in her right hand, her pencil; but she hadn’t drawn anything today. She tilted her head, the better to see the scene next door.

The Taylors’ house seemed to be made almost entirely of glass. From her perch in her room, Diana could see all of the goings-on. She could watch someone walk from the kitchen to the dining room, see them reappear on the stairs, and then in an upper-floor bedroom. Her vantage point gave her full access to one side of the house, like a page from a Richard Scarry storybook, a cross-section of a life shared. The notion of this, being part of something together, this version of family, was foreign and fascinating to Diana, whose family members seemed to exist on solitary planes, remote from one another. She watched now as Mrs Taylor, the Marianne Taylor, the famous fashion designer, called to one of her sons to help her reach something in a cupboard in the kitchen. Diana, so tall herself, thought of how she would like to do this small thing for her, retrieve something out of reach. Be useful and appreciated. Needed. Such a small act of kindness and teamwork. The eldest Taylor son, who responded to her call, easily grasped a box from the cupboard and lowered it for his mother. Diana could see that it featured a photo of some kitchen gadget on the front. Mrs Taylor smoothed her son’s hair and patted his cheek. He allowed this, then left the room. Diana’s gaze didn’t follow him but continued to watch Marianne as she opened the box in the kitchen. It was a mandoline, that dangerously sharp tool that looked and sounded like an instrument, for cutting food into paper-thin slices. Marianne ran her index finger slowly beside the blade, a motion so private in that interior space that Diana blinked, strangely moved. Something else caught her eye. A shadow, a movement in the Taylor yard.

Diana’s own brother, Keith.

He said it had been an accident, her arm breaking. It had happened at their holiday home, the summer cottage up north in Muskoka, one weekend in early June. All the Tony Toronto types had large cottages around the lake and, come June, Muskoka was overflowing with city wealth, gliding around on water skis. The Martins had been all together, as a family. Diana’s mother was inside the cottage, reading a book, their father on the balcony, at the barbeque. Keith was horsing around with the kids from a neighbouring cottage: Jodi and her brother, Mike, who had come to see if Keith and Diana wanted to hang out. They were taking turns racing down the hill from the cottage, across the dock to the water and jumping in the lake – a forested, rocky terrain that required dodging and weaving and speed. Mike held his father’s old track and field stopwatch, the yellowed cord hanging down from his hands. They were trying to best each other, see who was fastest from the time they started running to the time they hit the water.

Diana watched from some distance away. She too was strong and fast, and it looked like fun, but she had never participated in things like this. Because of Keith. Her entire life, he had bullied her, told her she sucked, that she was useless and slow and stupid. Her brother’s dismissal was as constant as air, as real as life itself. When she was younger, it had confused her. Their parents had always favoured Keith – their only son, their firstborn – and so it confounded her that he so relentlessly kept her down. She used to try to make him proud, assuming he was just hard to impress. But every achievement of hers was read as something that should have been his, something she stole. It was greed, paired with bloodlust. She had seen him enjoy causing fear and intimidation in younger kids at school, laugh loudly and cruelly at suffering. He was someone for whom the top, the best, was rightfully his, a position to be protected by any means necessary. And so Diana had learned to never threaten his birthright to happiness and satisfaction, to never risk drawing his attention. She pursued different sports, activities she knew bored him. It made little difference. Keith didn’t hate Diana, although she could see how someone might think that – other kids had remarked that he did. She wished he’d hated her; that would mean he considered her at all. He didn’t hate her; he loved his life. She was merely the closest threat, the nearest target. He worked in a broad, boorish style of bullying: name-calling, belittling, mocking. Her appearance, her height, her lack of friends. If she excelled physically, it was because she was a freak; if she did well academically, it was because she had no life. And so, mostly, Diana avoided his world, denying herself so many things.

But that day in June, when the kids were running down the hill, the sun flickering in the leaves, she wanted to be a part of it. She chose to take the risk, to be a kid in the summer at the lake and nothing more.

‘I want to try!’ She shouted, her hands cupped around her mouth, surprised by her own voice, usually deep and quiet, now shrill and girlish.

‘Yeah! Come on, Diana!’ cheered Jodi and Mike.

Keith turned to look at her. ‘Oh, this I gotta see,’ he sneered.

Keith was fifteen, almost sixteen, and his body was large and muscular. He was at that age, so close to childhood but appearing like a man. His mouth turned up in a cruel smile. He had won the race every time, and had no intention of losing. But Diana felt reckless, competitive, like she could best him and feel good about it, and maybe there wouldn’t be consequences at all. The lake, the cottage, the trick of the summer light made it all appear like family fun and it emboldened her. She grinned and jogged easily up the hill.

‘Yes, Diana,’ said Jodi. ‘You can take him down.’

‘Yeah, smoke him,’ laughed Mike. Neither thought this mattered at all, not really. They had moved into their cottage only the summer before, and having only seen Diana and Keith together occasionally, thought his jibes were just playful sibling teasing. They didn’t notice the way he was watching her as she considered her route down to the lake, making note of the tree stumps and branches that might slow her down. He began to walk down the hill himself, close to the dock.

‘I’ll watch from down here,’ he called up to them. Diana smiled at Jodi and Mike. Mike clicked the small silver button at the top of the stopwatch to reset it.

‘Ready?’ he asked.

Diana leaned into a sprinter’s stance. She squinted, her eyes on the dock.

‘Go!’ Mike pressed the stopwatch and Diana took off running, dirt and sticks flying out from under her as she careened down the hill towards the dock. She heard herself laughing and gasping, thrilled with the physicality, the action of it. Keith was leaning against a tree, watching. She neared him, closer, closer still, and, in the last moment, flicked her eyes at him and away from her path. His body moved slightly, angling, his own eyes narrowing. In that second, she doubted herself, lost her way, tripped on something – did he trip her? – and went flying, her body arching and smashing onto the dock with a sickening crack. She skidded across it and to a halt, her face close to the rocks that jutted out on either side of it, her left arm screaming in pain.

Later, Diana heard her mother ask Keith if he saw what happened.

‘She tripped. She’s so clumsy, I don’t know why she wanted to keep up with us in the first place. She shouldn’t have even tried.’

She never knew for certain why she’d fallen, but felt, instinctually, that to try and best Keith might cost her something greater than her arm one day. She spent the rest of the summer watching from the sidelines, both at home and at the cottage, her left arm in a large plaster cast. She devoted her time to drawing.

The Taylors, their Toronto neighbours, had always been a source of fascination for her. Marianne was so glamorous and talented; her only daughter, Aurelle, seemed like a girl out of a movie, she was so beautiful. Their life was like a moving magazine spread. Diana’s summer bore witness to theirs from her top-floor window. She had never been a recipient of the gestures of love and affection that came so easily to all the members of that family. The Martins never laughed like the Taylors did together. It was unaffected and appealing. Earnest. Aurelle was the inverse of Diana: she had an ease about her, an openness and natural charm, and her relationship with her mother was loving and affectionate. Diana’s fascination and obsession with their happiness often made her weep, sitting alone in her room, but she couldn’t stop watching. The mother-daughter relationship, the family she saw from her octagonal window brought her the warm, impossible comfort of a snow globe. She took the crumbs of their love and they sustained her; she made them permanent in her sketchbook so she could feel it again and again, drawing little scenes of their lives together. Her own family was remote at best, cruel at worst. Their large original brownstone lacked large windows and featured so much wood that Diana felt she lived trapped in an old, enormous tree Her parents were formal and distant, from another age. Keith relentlessly bullied and belittled and her parents turned their heads. All the while, Diana’s pain deepened and hardened.

She saw him now: Keith, in the Taylors’ yard, sloping across their deck with all the familiarity of one who has never been shut out. He was friends with one of the Taylor boys, Matt, and they were laughing, leaning against an outside wall, lighting a cigarette and sharing it between them. Looking back at the kitchen, at Marianne, who was slicing potatoes with her mandoline, Diana felt a sharp fury at Keith for ruining this moment, like a frat boy walking through a Mary Pratt painting. Her body tensed as soft rage flooded her veins and she felt a pleasurable pain in her healing arm.

She got up quickly and left the room, her chair tipping slightly. Back, forth, then righting itself.

3

Days after the rave: the first day of school at Rocky Barrens. Diana took a long drag from her cigarette and exhaled, closing her eyes. In that tiny moment, she felt it: deep contentment. Happiness. If it was a thing, she’d have described it as a clean, cool linen, a sheet pulled tight. She opened her eyes and looked. The lake, through the window where she stood, was calm, sparkling, and she knew it would be a crisp autumn temperature if she were to reach her hand in off the dock as she had so many times. Today, when they took the canoe across to campus for their first day of classes, they’d have to dress warmly, the air coming off the lake would be revitalizing and fresh. The maples were dazzling oranges and yellows, blazing between the pines. It was the best time of year. She looked behind her at Aurelle, deeply engrossed in a novel on the couch, twisting a strand of hair around a finger. She noted her girl-like innocence, her comfort here. Diana loved her friend’s passion for stories, her ability to immerse herself so completely, to escape entirely. Diana’s fingers itched for her pencil, for the chance to draw her just as she was then. She glanced out the window again, at the familiar landscape she’d known her whole life, but that had never felt like it was hers. It had always been Keith’s, forever his domain. But now, finally, she had a purchase on the thing, could grasp this place and give it new meaning: her life with Aurelle, a home together, a future. A chance to recreate herself. Something she had often dreamed of.

‘Do you want to take the car, or should we canoe across?’ she asked Aurelle, who now looked up, startled, returning to the present. Her eyes flicked out the window.

‘It looks chilly,’ Aurelle said doubtfully.

Diana smiled, and joined her on the couch. She reached for Aurelle’s hands and rubbed them between her own.

‘We’ll bundle up. It will be fun.’ She looked at the delicate watch on her own wrist. ‘We should get going, though. First day. Grab your stuff,’ she said in her cool clipped voice, standing up. She headed for the door, grabbing her satchel and light trench coat on her way. ‘I’ll meet you down there, OK? It’s a gorgeous day!’

Aurelle smiled then, too, Diana’s declarations contagious as always. It was gorgeous. And it was theirs to make of it what they wanted. She gathered her cigarettes and a binder from the table and put them into her school bag. She had her first class in an hour. She took a last look around the cottage and felt light, free. She shrugged on her shearling jean jacket and followed Diana outside.

Diana was down at the dock untying the canoe. She stood up and waited, eternally patient, her imposing figure cast against the water like a painting. Like the Alex Colville ones Diana had shown her once. Shielding her eyes, Aurelle looked across the lake and could just make out the large RBU sign and groups of students on the shore. Voices reaching across the water. She tossed her bag in the canoe and, grasping Diana’s warm hand to steady herself, climbed in, taking up her own paddle. She sat up front in the bow; she didn’t like the water really, wasn’t as strong at paddling as Diana, who seemed borne of the water itself. She felt Diana’s stroke behind her as the canoe shot easily forward, past the rocks that jutted out precariously close to the end of the dock, moving them with purpose directly across the lake towards the campus shore. Diana let out a cheerful ‘Ah!’ into the fresh air and Aurelle laughed, saying, ‘OK, OK, you’re right, this is pretty nice.’

It was early September, their first month as students at RBU, but to Aurelle, who leaned her head back into the morning sun, it was as though they’d always been here. Home, her life, the suffocation of fame, the universe that revolved around the Taylor family – it wasn’t here. It was behind her. This place was their own now, her family was Diana. It was just as Diana had said it would be when they moved in a few weeks prior. They adjusted immediately to the wild, forested campus and the way of life here. Like it’d been waiting for them. They could reinvent themselves.

My Diana, she called her, as if there could ever be another. Diana had rescued her, revived her, brought her back to life by giving her a new one. The possibility of something not predetermined for her. Diana made her feel safe, protected; just seeing her filled Aurelle up like a warm elixir. All this time her kindred spirit had literally been the girl next door. Aurelle’s only regret was that they hadn’t known each other until just over a year ago, but they made up for it now in spades. She had followed her friend, Diana, who had stridden away from her own family, her hand wrapped around Aurelle’s, and trusted that at Rocky Barrens, they could start fresh.

Young people were everywhere here. They roved – hungover, high, drunk, no matter the time of day or night – between the trees to get to one cabin-like building or another. Music rode on breezes, from windows, from boomboxes propped up on wooden stairs, songs mingling and canceling each other out. Its nickname was ‘Camp RBU’ and it truly did feel like summer camp at times. Students sat at the lake, gathered on the dock or at the little coffee shop up on the rocks, watching the rowing team skate across the lake, shouting in unison.

Diana and Aurelle were a part of all of it, but apart also. They’d decided early that they would live together in Diana’s family summer cottage, which was no rustic getaway, but a massive mansion in the woods across the lake from RBU. It was their home now: watching across the water, paddling back and forth in various states of sobriety, in their two-person canoe, their two-person club. They eschewed Mr Noodles and all-day pajamas, opting for a grown-up life. They made dinners together, drank wine, took advantage of their wealth and upbringing. Coats hung in the closet; shoes at the door.

‘Here, I’ve got my boots on, I’ll pull you in,’ Diana said, gingerly getting out of the canoe and easily hauling it into her favourite docking spot among some pines a distance away from the large dock. She offered Aurelle her hand and helped her out and up the bank. She reached into her pocket and shook a cigarette from a pack, offering one to Aurelle, cupping a hand around hers, then lighting her own, and they began their walk through the woods towards the main outcrop of cabins where classes were held. They passed a couple of students who blatantly stared at them, Diana nodding curtly, Aurelle ducking her head shyly.

They reached a fork in the path with a sign towards different campus buildings. Aurelle turned to Diana and said, ‘I’d better head this way. I’ve got class in a bit.’ She gestured towards the crop of cabins to her left where the Humanities courses were taught. Diana leaned down and briskly kissed her cheek, her breath smoky and warm. She smoothed Aurelle’s hair and gave her hand a final squeeze. I could put you in my pocket, Diana sometimes said to her. Becauseyou are so tiny, and I could keep you with me always.

‘OK, good luck. I’m going to the Den for my first studio class. Find me later? Or I’ll find you.’ Aurelle smiled and nodded, and Diana turned, walking purposefully, her long strides taking her away into the trees. Aurelle felt the happy warmth of her presence long after she’d disappeared from view.

As Diana approached the Art Den, she was reminded of her first time seeing it. An almost perfect day.

Before Aurelle had become part of her life, before all of this. She was at the cottage for the weekend, enduring her brother’s painful presence in her favourite place. While Keith and his friends all slept off their hangovers, Diana had slipped out onto the water in the kayak. It settled her. She couldn’t let him get to her, define her. Control. She took deep breaths. This lake was her sanctuary; it was worth the trouble of Keith and his friends to have these peaceful moments in the water, alone. She paddled away from the cottage, towards that famous college that had always been on her radar, Rocky Barrens University.

Classes were out, and it was quiet. She docked the canoe and walked around the RBU boathouse, which was locked, and read the signs for students about signing out water sports equipment, hours, safety. It looked like it had been there since the college’s early days, back in the 60s when it had first opened. She felt a pang, wishing she could be a student there, thinking it could never be. She loved that the school had a history, a backstory: that when it had originally opened, it hadn’t had the infrastructure to deal with the relentless northern winters, so had closed indefinitely and just reopened recently. Many of the hallmarks of the college’s heyday in the 60s remained in the lettering of signs and the murals and mosaics on the sides of the cottage-like buildings. And, despite its decades-long hiatus, RBU had a very strong academic and sports reputation as a small, elite school for artists and athletes. The rowing team at RBU was already quickly racking up awards in tournaments – and so, of course, it was determined by her family that this was where Keith would attend.

He will thrive there, she’d heard her father saying to a friend. I bet he becomes the captain of the rowing team in his first year. Keith, too, had spoken of the place as though it was already his, acted like the resident expert on the college. Her parents never thought of her as RBU material, though. Diana is more Ivy League, obviously, either here or in the US. Diana didn’t want that, but her family didn’t take the time to know her. She was already a gifted artist and her research into the faculty at RBU excited her. She knew that it was she, not Keith, who would fit at RBU, but gave up on the hope of it. She mourned it as though she’d already lost: she could never attend the same school as him. He would dominate the place, ruin the unspoiled landscape for her, turning her fantasy school into a house built from empty beer cans.

She had strolled through the campus, looking in windows, smiling at the people who remained. Some faculty and staff along with a few students were there for the summer so it wasn’t vacant, but had a peacefulness to it. She didn’t feel like an outsider, like she shouldn’t be there. It was an easy campus to navigate. There were wooden, arrow-shaped signs nailed to trees and signposts for buildings with names like Dark Adaption Observatory, Literae Humaniores, and The Art Den. The buildings themselves were log cabins – large, small, one or two storey – with well-trod steps and railings, bulletin boards in front of each one advertising some event or another related to that particular field of study. She learned that there were stargazing evenings up at Rocky Barrens proper, which she knew was some distance from the campus itself; a literal barren landscape where people gathered to look at the sky. She learned about parties at the Art Den, about a group that hiked every morning (Newcomers welcome! No experience necessary!), about Polar Bear Dips and Spaghetti Dinner Fundraisers for the Swim Team. She saw postings for sublets on paper with carefully cut tabs and handwritten phone numbers scrawled sideways. A few torn off. She wondered if the people who took them lived there now. Made lunches in a little kitchen. Showered in a small but neat bathroom. Majored in English Lit. Or Women’s Studies. Classical Studies. Art.

She had paddled back towards the family cottage that morning, the sun higher. There were horse flies buzzing loudly around her and a mist coming off the lake as the day warmed up. She saw a loon dive then reappear further along. She looked at the cottage as it came into view and felt a warmth for it, a generosity. She smiled. Her life could be different, maybe.

And then, suddenly, it was.

Later, she said that it had been such a nice morning. A perfect morning. She didn’t say it had been perfect because she’d been alone, away from Keith and his friends; that being far from family always made her less lonely. She left that part out. She told a version. She learned there are always versions.

She was here now, a different person in a different time. With Aurelle at Rocky Barrens – her fantasy life made possible. Having grown up going to the cottage in Keith’s shadow, under the thumb of his cruelty, she now had no reservations about being herself, taking up space. Up north. The entire place was surrounded by height. The pines reached up, straight and scraggy, the maples grew everywhere they found room, ferociously persistent.

She pushed the door of the Art Den open and breathed deeply, the smell of oil paint calming every painful memory and welcoming her. She held her chin in the prideful way she knew people hated and envied, and entered. It was Day One.

4

Toronto, 1994. Before Diana, before RBU. Before any and all of it. Aurelle was a teenager trying to become someone. Or, at least, to separate from someone else. Aurelle loved her mother, of course she did. Marianne Taylor was kind and affectionate, and seemed to be universally adored and admired. She was the famous fashion designer of couture lines of apparel, was the feature of fashion shows, the choice of celebrities and stylists. But she was also, somehow, miraculously, a loving mother, a devoted wife – an object of envy and desire. Sun-kissed, talented, blessed with a large family, she had it all and shared it. Aurelle loved that, she did, but there were times she envied everyone with regular parents.

The Taylors lived in Rosedale, an affluent area of Toronto. People who used words like affluent lived there. Their house, a large brownstone, had been gutted and radically renovated to feature enormous windows, open-plan rooms. It was one of the oldest homes in the neighbourhood, and regularly photographed by curious onlookers and paparazzi hoping to get shots of the famous Marianne Taylor family in their natural habitat. Since Aurelle was a baby, there had been photographers documenting her life and that of her brothers, both in the house and whenever they left. The sound of clicking cameras became a beating heart. Even now, there are photos published of the house in its heyday, its period of youth and glamour. In some of them, you can see Aurelle, looking off to the side, trying to get away. People zoom in on her face, analyze it for some evidence of what would come later, some clue. Zooming in until she is just a muddled blur of pixels, a smudge of paint, not a girl at all.

Aurelle was often asked about her life, but these questions always contained the expected answer. Isn’t it so fun at your house?Don’t you just love living there? Or even the frank statement, You are so lucky. People asked her what her mother was like, but they had their own ideas. Aurelle tried to see her life through others’ eyes. Marianne was perfect, of course; she was glamourous and generous, her smile a row of gleaming stars that shone out onto all of them, and Aurelle and her family were brighter under her sun. And. But. Aurelle smiled without showing her teeth. She craved quiet corners of the house and yard where no one was laughing or playing music, where no one was at all. And then, in those quiet spaces, she immediately felt her solitude so keenly that it hurt. It was the conundrum of her life at home. She wondered what was wrong with her. She felt guilty for wanting something else.

Now in her twelfth grade, with only this and one more year left of high school, Aurelle was trying to be more or less, but, at the very least, different. One afternoon at her locker, she overheard some kids talking about going to a rave. It was easy for Aurelle to join conversations, to be part of a group. She simply held the gaze of one of the girls, smiled, said something like, Where are you guys going tonight? And they always opened their circle. Easy. She was likable. Really nice. Being nice was a currency in which Aurelle knew how to trade. Nice was smiling at strangers all day so that no one would say she was a snob and a bitch or that she thought she was better than everyone. Nice was answering questions about her famous mother from anyone who asked, even if they were shouted to her in a crowd at the cafeteria. Nice was a gentle laugh, a self-conscious touching of her hair, a looking down of her eyes. Sometimes her cheeks hurt at the end of the day from being nice for so long. The thing she read most about herself in articles about her family were quotes from schoolmates: She’s actually really nice.

‘We’re going to a rave. Do you…’ – an exchanged look – ‘Do you wanna come?’

They weren’t her friends, not really. Aurelle didn’t actually have any close friends, although anyone at the school would have claimed the opposite. Friends: girls her mother insisted she invite over, or who came to the house with her brothers; girls who flocked round and helped her mom in the kitchen, who had sleepovers and did face masks in her bathroom. They were fun and funny and shrieked about gossip and cried about breakups. Aurelle never felt close to any of them. But they were easygoing and they had invited her, and Aurelle wanted to do and be something different, anonymous, away from her normal. A rave was perfect. Yes.

The plan was to meet at Rosedale subway station at midnight. Aurelle waited until her family was asleep, the moonlight pouring through her bedroom windows, and pulled on a pair of jeans that were fitted at the hips and flared wide, had little rainbows on the pockets. She wasn’t much into techno and rave culture, but had a few items she could make work. Going through her shirts, however, she found nothing she wanted to wear and began to feel panicky about being late, missing her chance to meet up with the others. She padded lightly down the stairs to her mother’s studio, hoping to find something she could wear there. Later, she heard her mother tell this story in interviews, Aurelle’s own life reinterpreted, embellishing details here and there to make it more exciting. It was something she became used to over time. But here, now: quietly turning the knob, she crept into the room and switched on a small table lamp. On one of Marianne’s work tables was a T-shirt spread out beside some notes. Marianne had been trying to crack into a younger market, and this was clearly one of the lines she was toying with. The shirt was cropped, white, and had a large, stylized cherry on the front in bright red. The piece was unfinished, the boxy bottom unhemmed and roughly cut, but Aurelle pulled it over her head and looked down at herself, admiring how the shirt showed off her midriff, fit snuggly over her breasts. She clicked off the lamp, left the room, left the house, making her way out into the night and, unknowingly, into pop culture memory. She didn’t see someone watching her from an upstairs window next door; she moved into the darkness, away from her house with a perceived, treasured anonymity.

It was like a dream. A subway ride in the darkness, moving with a crowd of partiers into a large building on Richmond Street, the music filling her body with a pulse that felt elemental, instinctual. The other kids had shared some Ecstasy with Aurelle when they met at the subway station, and soon she was just one more kid in a mob of young people dancing, her mouth in a permanent grin that was real and true. Aurelle had only ever tried pot before, and the thrill of experimenting with other drugs was a kind of high in itself. The loosening of the Ecstasy, the way it extended and enriched everything from feelings to touch to colours, was like walking through a doorway into another world – a part of her felt she’d happily spend the rest of her life this way. Here, dancing with her arms over her head, feeling the sensual pleasure of strangers’ hands on her bare waist, on her mouth, in her hair, she was both seen – deeply, truly seen – and unseen. Free. It was a dazzling hyperreality and she knew she wanted more.

Lying in bed the next day, knowing this was possible, that she could disappear and escape fame and family, that there was a life outside the Taylor household, was the most delicious secret. But two days later she was brought back down, rooted once more to her mother. A photo of Aurelle, dancing, eyes closed, arms stretched over her head, the cherry T-shirt clearly shown, hugging her body, was the large, feature photo of the style section in the paper. Her name, but more importantly, her mother’s name, captioned below. Aurelle cringed at the image, at her private moment of abandon made public. Her face burned. Initially fearful she’d get in trouble, Aurelle was surprised when the opposite happened: orders for the same print, and others from whatever line it came from, started piling up immediately, the phone ringing constantly. Marianne kissed the top of her daughter’s head, lips pressing down hard in excitement. ‘Oh, you terrible, rebellious, genius girl!’ she laughed. ‘You are the best accidental, guerilla ad campaign ever!’

Aurelle stared again at the photo of herself, caught in a moment of joyful freedom, unaware at the time that anyone was watching, taking a photo they would later sell. She forced a smile up at her mother. ‘Glad I could help.’

‘Help? Oh, honey, you have single-handedly opened up a whole new market.’

The MT line of rave wear, ignited by Aurelle, exploded. She became known as ‘the girl in the cherry tee,’ a sexualized calling card that embarrassed her but thrilled her mother. Since then, she often asked Aurelle to wear the clothes, to school, to parties, anywhere: They suit you so well, darling! She encouraged Aurelle to go to more raves, giving her money and grilling her the next morning about what people wore. Aurelle did go, becoming a familiar face on the Toronto rave scene and a key part of the MT brand, neither of which she’d really wanted. It wasn’t the same. It was no longer her own. Everything was her mother’s. Her parents had framed the unfinished shirt with the cherry on it. It hung, under glass, in the front hall of their home. The home where anything could happen. Where your very self could be on display. She was so lucky to even have the option of rejecting this gift. Others would kill for it.

The Taylor house: a sunny, well-lit dream home. It was full of strange little rooms, nooks and crannies, many floors and different stairways to get to them. All over were reminders of Marianne’s enterprise, like another member of the family. Along with the framed MTT-shirt and corresponding photo of Aurelle, portraits from photo shoots for Vogue, In Style, the New York Times all hung throughout the house. Tributes to Marianne Taylor, one of the most famous clothing brands in the world, who had recently moved into urban rave wear. Rave Queen. She could do anything. There was a large handbag called ‘The Aurelle’ that many of Aurelle’s high school classmates owned; she couldn’t tell if it was intended ironically or not. Her mother had named handbags and tote bags and wallets and sneakers after all of her children, capitalizing on the public interest in her family. Aurelle was the youngest of four, and the only daughter, all the children close in age. Mike, James, Matt and Aurelle. Mike and James were away at college now, but home fairly often, which was always a cause for celebration, for a party.

Aurelle drifted through the house, a lonely figurehead. She preferred to be a room away, listening as the action took place from a distance. Her family largely left her alone unless there was a photographer or interviewer inside: then she was summoned, cajoled, complimented, and then she needed to turn it on, to smile and offer sound bites about her mother, the clothes, the famous shirt.

‘I mean,’ Marianne laughed recently, seated beside Aurelle at dinner. ‘I can hardly be the face of the company anymore. I’m the aging queen.’ She rolled her eyes in self-deprecation. ‘We need you