Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

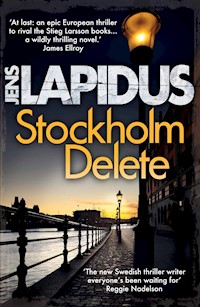

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Stockholm Noir

- Sprache: Englisch

Stockholm Delete is a superbly gritty thriller which gets right to the heart of the Stockholm criminal world. Now a major Swedish TV series, with plans to bring it to UK audiences. Emilie Jansson has just been made partner at a prestigious law firm when she is asked to work with an unusual partner. Teddy is an ex-con trying to stay on the right side of the law while working as the firm's fixer and Special Investigator. Meanwhile, a body is discovered in a remote house in the country after what looks like an attempted robbery - and a severely wounded man found near the scene is soon in the frame for murder. Emilie takes on the role of his defence lawyer. But when the trail of evidence leads back to her partner Teddy's wayward past, Emilie begins to wonder what she's taken on... In Stockholm Delete, Emilie and Teddy become entangled in a complex and dangerous web with deep connections to Stockholm's criminal underworld. Both will be tested in terrible ways. But can they survive long enough to uncover the truth?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 716

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JENS LAPIDUS

STOCKHOLM DELETE

Jens Lapidus is a criminal defense lawyer who represents some of Sweden’s most notorious underworld criminals. He is the author of the Stockholm Noir trilogy, three of the bestselling Swedish novels of this past decade: Easy Money, Never Fuck Up, and Life Deluxe. He lives in Stockholm with his wife.

ALSO BY JENS LAPIDUS

Easy Money

Never Fuck Up

Life Deluxe

First published in the United States in 2017 by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in Sweden as STHLM Delete by Wahlström & Widstrand, Stockholm, in 2015.

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jens Lapidus, 2015

The moral right of Jens Lapidus to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 176 3

Export trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 174 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 175 6

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Värmdö

Tony Catalhöyük didn’t love his job. His real dream was to be a policeman. But he’d failed to get into the training course twice. He had perfect vision and hearing, and he’d passed the physical tests with ease. He didn’t have any of the inadmissible health problems, either, and his grades were good enough.

It was the psychological tests where it had all gone wrong. They’d said that he didn’t see himself as a part of the wider group. That he tested as a lone wolf. When he called the recruitment people, they just parroted more of the same story. They repeated the same words as the report, over and over again.

The sky had started to lighten, but the forest around him was still dark. He was driving quite a bit above the speed limit, but his bosses normally encouraged that, at least during night shifts. Not that they would ever officially admit it. “We can’t just take our time out there,” they said. “We should either be at the monitoring center or with our customers, where we can put ourselves to some use. People appreciate us getting to them quickly, even if we are just caretakers in uniform.”

Tony hated that: caretakers in uniform. He was no caretaker. He was there to fight the bad guys, just like the police officer he planned on becoming someday.

The alarm had come in about fifteen minutes earlier, from a house in the woods on Värmdö island, to the east of Stockholm. It was a power outage, though the electricity had come on again after a few minutes.

Without slowing down, he turned onto a smaller road to the right. He hadn’t been along this road before, but the risk of meeting another car was virtually zero. There were hardly any houses around.

He was only about a quarter mile from the house when he spotted something behind a big bush on the verge up ahead. It looked like a car in the ditch on the right. Maybe he should stop to see if something had happened? No, the alarm had to be checked within twenty-five minutes. That’s what their customer guarantee said, anyway.

The gravel in the courtyard crunched as he pulled up.

There was a garage beyond the house, but he couldn’t see any cars in it.

It was quiet. The alarm was no longer sounding. Tony assumed the owner must’ve turned it off. That wasn’t so unusual, either. It was the middle of the night, and their customers usually just went back to sleep after turning off a false alarm.

But it was too quiet here somehow, too still. Like everything was holding its breath. He took out his cell phone and tried calling the customer again. No one answered.

The front door was painted yellow, with a little window set into it. The place looked dark inside. Tony held down the bell, heard it ring faintly.

No one came to the door, so he rang the bell again. This time, he pressed it down for even longer.

He knew what to do in this kind of situation. SP: standard procedure. Visual inspection of the exterior, check the area. Make notes. Report back to HQ.

Any discarded tools in the damp grass, broken electricity enclosures. Forced doors, muddy footprints on the porch, broken windows.

That was the kind of thing he was meant to look out for.

Then his eyes fell on one of the typical causes of false alarms—an open window on the ground floor. Normally, it was down to nothing more than the customer forgetting to close it. In this instance, though, the alarm had gone off because of a power outage, not because someone had opened a window.

Tony went over to it. The grass was long and made his combat boots damp. The room inside was dark.

When he stood on his tiptoes to look in, he realized that a circular hole had been cut into both panes of glass. It was a classic, albeit advanced, burglary technique, and one that he’d seen only twice before.

This was no false alarm. Someone had tried to cut the power. His pulse picked up.

He took a few steps away from the house, called the monitoring center again, and told them what he’d found—that it was definitely a break-in.

“Ongoing or finished?”

“I don’t know. There could still be someone inside, cleaning up.”

Tony shoved his phone back into its holder and walked around the edge of the house, toward the front door.

He made up his mind that if anything shady was still going on, he’d put a stop to it.

He looked at the front door again. This time, he tried the handle and realized it was unlocked.

He stepped into the house.

The coats and jackets hanging on hooks in the narrow hallway fluttered as he opened the door. The place smelled of old wood and open fires.

He felt for his flashlight.

To the right, a staircase led upstairs. Straight ahead, he could see the kitchen.

Tony took out his collapsible baton and grasped it in his hand. Black hardened steel, the longest model—twenty-six inches. In training, they often used them to practice attack and defense. He’d never needed to use it in service. There was a first time for everything, he thought.

He took a step forward. Heard the crunch of broken glass. He bent down with the flashlight. The hallway floor was covered in tiny shards of glass.

The kitchen seemed clean and tidy. He saw the wide-open window again, this time from the eating area. A big, round clock hung on the wall. It showed quarter past four in the morning.

The room was open plan, the living room on his right.

There really wasn’t much furniture.

An armchair. A coffee table.

Something on the floor behind the coffee table.

He moved closer.

It was a body.

He felt the nausea rise up in him like a jolt through his body.

The head. There was no face left; someone had blown their head to pieces.

Tony’s vomit hit the rug.

He looked down at the floor.

Blood everywhere.

He was shouting and crying into the phone.

“Calm down. I can’t hear what you’re saying.”

“It’s a fucking murder, a bloodbath. I’m telling you, he wasn’t breathing. Send the police, an ambulance, this is the most messed-up thing I’ve ever seen.”

“Is anyone else there?”

Tony looked around. He hadn’t even thought of that.

“I can’t see anyone. Should I search the house?”

“That’s up to you. Did you see anything strange outside?”

“No, not really.”

“Did you see anything strange on the way to the house?”

He ran out onto the porch again. He’d almost forgotten.

“What’re you doing, Tony? What’s going on?”

Back along the road he’d driven in on.

“Fuck, there was a car in the ditch. I saw it when I drove past.”

He started to run.

“I’m calling the police, but keep your phone on you. Follow standard procedure.”

He felt better now, out in the fresh air. He tried to forget what he’d just seen; the real police could take care of that. Right now, he was just glad he wasn’t one of them.

A caretaker in uniform.

In the faint light of morning, the dark blue car almost seemed to be burrowing its way into the earth next to the bush. When he pushed the foliage to one side, he saw that the front half was completely crumpled. The car must have gone at least fifty feet into the ditch.

Tony saw the torn earth in its tracks. In the background, the spruce trees were still dark. The bushes had hidden how smashed-up the car was when he drove past earlier.

He moved forward. The baton was back in his hand.

It looked like there was smoke rising from under the hood, or maybe it was just dust swirling in the glare of the headlights.

The mud squelched beneath his feet, and he had to hold on to the thin grass to keep his balance.

It was a Volvo, a V60.

He tried to see whether there was anyone inside, but it was hard to make out.

He clambered alongside the car and peered in from one side.

Then he saw. There was someone slumped forward in the driver’s seat.

“Hello?”

The person didn’t move.

The windshield had been forced inward, and the thousands of cracks in the glass reminded him of ice. It hadn’t shattered.

Tony bent down and opened the driver’s door. The air bag had discharged.

The driver seemed to be a youngish man, probably in his twenties, blond hair.

The limp air bag looked like a white plastic bag spread over the wheel.

Unconscious, maybe dead.

Tony prodded the man’s arm with the tip of his baton.

No reaction.

PART I

MAY

1

Eat shit.

Nikola had been forced to take shit for so long now.

One whole year he’d been here.

But it was almost over. Tomorrow: the last day. Thank God. He was almost ready to start going to church with Grandpa Bojan.

He was nineteen. Sweden was messed up like that—they could lock you up somewhere like this even though you weren’t a minor. Though that was his majka’s fault. Linda, his always-fucking-nagging mom. She’d threatened to throw him out, cut all ties with him. And worse: she’d used Teddy as a threat. Honestly, that was what got to Nikola—the risk that Teddy would be disappointed. He loved him more than the freshest snus in the shop, more than all the ganja in the world, sometimes even more than the crew. The guys he’d grown up with, his brothers.

Teddy: his uncle.

Teddy: his idol. An icon. A role model. He only knew one person you could even compare him with. Isak.

That hadn’t been enough, though. The amount of community service, all that crap, it got too high. The fines too big. The whining from social services too loud. Linda had wanted him to go into custody. She wanted her own son to be put into a drug-free, fun-free, completely pussy-free care home.

So that’s where he’d been the past year. Spillersboda Young Offenders’ Institute.

Care shall be decreed if, through the abuse of addictive substances, criminal activity, or any other socially destructive behavior, the individual subjects his/her health or development to a significant risk of damage.

Fuck the place: he’d heard that paragraph fourteen million times by now.

It was still worthless.

Every other minute, the same thought going through his head. Like a broken record by some tired old house DJ. The chorus on rewind: fucking Mom, fucking Mom, fucking Mom.

“I’ve tried to do everything for you, Nikola.” That was what she usually said when he went home on release. “Maybe things would’ve been different if your dad had been around.”

“But I’ve had Teddy.”

Linda would shake her head. “You think? Your uncle’s been inside eight of the past nine years. Is that what you call being around?”

Nikola was sitting at the back of the classroom. Like usual. Eating s-h-i-t. They really were trying to keep him down.

Every now and then, a few new words would appear in the chorus: fucking Sandra, fucking Sandra, fucking cunting Sandra. . . .

She was his so-called course support officer here. She talked about job applications. You need to be able to present yourself well, write a personal statement, know how to kiss ass. Nikola had trouble working out the point of all her talk: he’d chosen a vocational program just so he didn’t have to sit around talking crap endlessly. And besides, he had no plans for a regular nine-to-five life, or even cash-in-hand manual work somewhere. There were much quicker ways to make some dough. He knew that from experience. The stuff they did for Yusuf paid off straight away.

Mini conversation group. Just Nikola and five other guys, once every week. The rest of the time, they expected him to turn up at the work experience place they’d organized in Åkersberga: George Samuel Electrical. There was nothing wrong with George, but Nikola just couldn’t be bothered.

According to the head of Spillersboda, and according to his mom, it was good for him to have group hours on top of the work experience. “It increases your ability to concentrate. You might not pass Swedish, but it’s still good to be able to read properly.” They went on and on worse than the drunks on the park benches in Ronna. ’Course he could read. His grandpa was the biggest book lover ever, for God’s sake: the reading genius from Belgrade. He’d been teaching Nikola literary magic since he was six, sat by his bed and plowed through the good old stuff. Treasure Island, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, The Mysterious Island.

Nikola wanted to fly under the radar, float like oil on water. He wanted to be a shadow, live life the way he wanted. Not be caged up in a classroom. Not controlled by any stupid abbreviations or acronyms.

Anyway: it was almost time. His twelve months in the ass end of boredom would soon be over.

Life would have some meaning again.

Life would be Life again. Things had already started to happen. They knew he was on the way out. Yusuf had been in touch to ask if Nikola would give them a hand with a thing in a couple of days.

Some kind of guard duty. Not just any old small job: this was a negotiation. Their own law court. A trial between two warring clans in Södertälje.

And Isak would be the judge. He’d decide the matter—a replacement for the system that had decided to lock up Nicko here.

Man, Isak. It was a step up.

But Nikola hadn’t said yes yet.

Stockholm County Police Authority

Interview with Mats Emanuelsson, 10 December 2010

Interview leader: Joakim Sundén

Location: Kronoberg Remand Prison

Time: 14:05–14:11

INTERVIEW

Transcript of interview dialogue

JS: Just so you know, I’m going to be recording everything we say here today.

M: Okay.

JS: We’re in the interview room, Kronoberg Remand Prison, and it’s the tenth of December, 2010. With me here, I have the suspect, Mats Emanuelsson, forty-four years of age. Correct?

M: Yes.

JS: And you agree for this interview to go ahead without a lawyer?

M: Uh, what does that mean?

JS: It’s not unusual. You’ll be out of here much quicker if we forget about contacting the courts; they have to get in touch with a lawyer, who then needs to have the time to come over. Look, I’ll put it like this: if you want a lawyer, I can’t promise we’ll manage this interview today or tomorrow. And that means you’ll go back to your cell to wait.

M: But . . . I panic when I’m locked up. I got kidnapped once, did you know that?

JS: No, I didn’t. What happened?

M: They abducted me, nailed me into a box. It was about five years ago now. I can’t cope with stuff like this. . . . I’ve seen a psychologist about the claustrophobia. I need to get out of here as quickly as possible.

JS: Well, okay, then I suggest we get started without a lawyer, and if you feel like you want to stop, just let me know.

M: Yeah, let’s do that, then. I need to get out of here.

JS: In that case, I’d like to start by talking about why you were arrested. You’re suspected of aiding in a drug offense in Gamla stan the day before yesterday. It’s suspected that, in agreement and partnership with Sebastian Petrovic, or Sebbe as he seems to be known, you helped in the handover of an unknown quantity of narcotics. Do you understand?

M: A drug offense?

JS: Yes, that’s the claim.

M: Are you sure?

JS: Completely sure. Shouldn’t I be?

M: Is there anything else?

JS: I can’t go into that right now. But I’d like to know your thoughts on this.

M: I’ve got nothing to do with that.

JS: So you deny any crime?

M: Yes, of course.

JS: In that case, there are a few more questions I’d like to ask.

M: Okay.

JS: What exactly were you doing in Gamla stan?

M: Nothing much, I was just there.

JS: Do you know Sebastian Petrovic?

M: No comment.

JS: Do you know who he is?

M: No comment. Is he being held?

JS: You don’t want to say whether you know him, but you want to know if he’s being held?

M: Yes.

JS: Well, since it would be public knowledge if he was being remanded in custody, I can tell you that he’s not being held. He’s a free man. I’d like to ask you a few more questions.

M: Right.

JS: Does the Range Rover, registration number MGF 445, belong to you?

M: No comment.

JS: Do you know who Sebbe was meeting in Gamla stan?

M: No comment.

JS: Do you know what he was doing there?

M: No comment.

JS: You have no comment about anything?

M: No, I really don’t. I told you already, it’s got nothing to do with me. I don’t know why I’m here. I just need to get out. My head’s going to burst in here. . . .

JS: You were involved in the incident the day before yesterday.

M: I don’t know anything. That’s not my world, drugs . . .

JS: No, I see that. I’m surprised, if I’m completely honest. Okay, we might have to do things another way. Wait here, I’ll switch off the tape recorder, and we can take a little break.

Interview terminated, 14:11.

MEMORANDUM 1

Transcript of dialogue

JS: The tape recorder’s off, so this isn’t a formal interview anymore. Think of it as a conversation. Just between me and you.

M: What does that mean?

JS: It means we can be freer in what we say. I won’t report any of this to anyone, not if you don’t want me to. And I’ll be straight with you, Mats, I’ve done a bit of research on you. You’ve got two kids, you had an ordinary job, and it’s true: you were kidnapped a few years ago. That must’ve been awful. You shouldn’t be locked up somewhere like this.

M: Can’t you just let me go, then? I’ve been here almost two days. I’m still traumatized from before. I’ve been through too much crap. Please, I’m begging you. I feel really bad in here.

JS: The thing is, we’re talking about a drug offense here. We’ve been using covert measures against certain people in this investigation—not you, but others.

M: What does that mean?

JS: Covert wiretapping of rooms, phone tapping, surveillance. We’ve got strong evidence. You’ll be convicted, I can say that with certainty. You’ll get at least ten years. And I don’t really think prison’s the right place for you, either.

M: But . . . (sound of crying) . . . I can’t be here . . . it’s been going on for years now.

JS: You’ll be sent to Kumla for a couple of years first, that’s the toughest jail in the country, and I’m sure you know what happens to people like you there. It’s not a fun place for softies. . . .

M: But . . . but . . . (inaudible)

JS: I know. None of this can be easy. Wait a second, I’ll get some tissues.

M: (Inaudible)

JS: There you go.

M: Thanks . . . (sniffing sound)

JS: Look, I know this is awful, but I’m a straight talker. It’s like this: I have a proposal for you. It’s a bit outside the box, but like I said, I don’t think you fit in here.

M: Please, tell me. I’ll do anything.

JS: It’s pretty simple. We understand you’ve had extensive contact with certain people who are of interest to us—we’ve seen and heard this, if you see what I mean. So, I want to know everything about them. I want to know what you’ve been working on. And if you can help me with that, then I promise we’ll keep things like this. No interviews, no recordings, no judges or lawyers. Your name won’t appear anywhere. And then I can help you in return.

M: You’ll let me go?

JS: If you help with this, I’ll let you go and we won’t take things any further. We’ll do a deal, you and I, do you understand what I mean?

M: I don’t know. . . .

JS: Think about it. Weigh up your different options. Eight, maybe ten years in Kumla versus a few hours talking to me.

M: It could be awkward . . . It’s dangerous. I’ve been through a lot, believe me.

JS: Yeah, that’s what I suspected. But you’re not one of the lowlifes. You’re normal. And if you go along with my suggestion, it has to be your own decision. I can’t force you. But what I can do is arrange the guarantees you need.

M: What about my kids?

JS: I’m only going to use what you say as a basis for further investigation. You’ll never need to testify or be named in any way. You’ll be under an alias, “Marina,” and I’ll be the only one who knows about it. Complete secrecy. You don’t need to worry about yourself or your kids. We can take a break now, if you like. I’m going to go out, so you can have a while to think.

M: Yeah, okay.

JS: Good. Just remember: at least ten years. Kumla. Or a couple of hours of talking.

2

They made small talk as they waited in the velvet-clad armchairs and sofas. Emelie knew a few of the others from before. She’d studied with some of them and met others at Swedish Bar Association training courses—one of them was even her colleague at work.

But beneath all the niceties there was tension. Of course: one by one, they were being called in to see the examiners. They had been asked to put their phones into small plastic pouches on a table at the end of the hall. All they were allowed was paper, a pen, and a folder containing the ethical guidelines and disciplinary committee’s questions.

It was time: very soon, she would be called in to her examination. The verbal exam, which would determine whether she would become a lawyer. Everything up to this point had, more or less, been a journey toward this goal. Twelve years of school followed by a year abroad in Paris—though she’d spent most of her time there partying in the Bastille area, she’d also learned fluent French—and then three and a half years as a law student before she gained her bachelor’s degree. Finally three years of work as a legal associate with the Leijon law firm.

During that time, she had taken Swedish Bar Association courses on ethics and professional regulations. She’d gathered all the necessary references. It wasn’t like applying for a normal job, where you just gave the names and contact details of your two favorite bosses. No, the Swedish Bar Association wanted the names and addresses, plus an account of the context in which you’d met, of all the opposing lawyers and judges you’d ever faced.

For Emelie, that hadn’t actually been too extensive. For the most part, the partners had fronted the cases she’d been involved in. But still, that was more than twenty people they were talking about. Each of them had to be contacted by the Bar, and all had to give their opinion on whether she was worthy of being allowed entry into their holy chamber.

And now, today, the final exam. If she made it through this, the rest would be pure formality. She would soon be able to give herself the title of lawyer.

“Emelie Jansson,” a voice called from the hallway.

It was her turn.

The examiner handed her an 8½" x 11" sheet of paper covered in text. She now had twenty minutes to think through the issue, prepare her presentation, and plan for the cross-examination. She went into a separate room, furnished with nothing but an oak desk and chair. A copper engraving representing some old case was hanging on the wall. She glanced through the first point.

QUESTION A

Discuss the questions of an ethical and professional technical nature arising in the situations apparent in the below account.

The English businessman Mr. Sheffield has made contact with the legal firm Vipps, and asked for help with the acquisition of a property complex in Gothenburg.

Mr. Sheffield tells the lawyer, Mia Martinsson, that roughly ten years ago he worked with the law firm. This was when the previous partner, Sune Storm, helped him with a complex matter. Mr. Sheffield says that he “really feels like a client of the firm, and expects assistance thereafter.”

After several weeks of correspondence with Mr. Sheffield, Mia starts to feel slightly hesitant about who Mr. Sheffield really is. He does not require any bank loans, and wants to transfer the entire purchase sum, 220 million kronor, to one of the law firm’s client accounts. The transfer will not, however, come from Mr. Sheffield’s account in the UK, but from a company based in the British Virgin Islands.

Emelie underlined several words in the question, and picked up the folder of regulations. She quickly put it back down again. Before she started searching for clauses, she needed to think. Identify the actual issues. The ethical pitfalls.

Shouldn’t the firm and the lawyer have run some kind of check on the client? Made a copy of his identification documents, run him through the firm’s conflict-of-interest database? Should Mr. Sheffield really be regarded as their client, just because he had been ten years earlier? When did a client relationship really become a reality? And what were the Financial Supervisory Authority’s rules when it came to checking and preventing money laundering?

She jotted down some notes.

Eventually, she heard a knock at the door: her time was up. The twenty minutes had passed much more quickly than she’d thought. She’d dealt with the questions as best she could, four situations similar to the one about the lawyer, Martinsson, and Mr. Sheffield. Each of them contained different problem areas. The firm community, witness management, committee questions. Conflict of interest.

The examiner was a lawyer in his sixties, a man with an incredibly well-groomed mustache, and the external examiner was a woman, probably about ten years younger than him—though she was trying to look like she was twenty. Both were formally dressed: the man in a dark blue suit and tie, and the woman in a burgundy dress.

“So, let’s start with the lawyer, Mia Martinsson? How should she act?” the examiner asked.

That had been three weeks ago.

Today, Emelie was in the office. She needed to work, but her mind was elsewhere. They might get in touch at any moment.

The phone rang.

“Hi, it’s Mom.”

“Hi.”

“How are you?”

“I thought you were someone else. I find out today.”

“Find out what? Something at work?”

“Kinda. If I passed the exam and my application went through. Whether I become a lawyer or not.”

“Oh, that’s exciting. Congratulations. Does that mean a pay raise?”

“I haven’t even found out yet, but there probably won’t be any pay raise. It doesn’t mean all that much in this firm. Being a lawyer has the most formal value for people working on criminal cases—you need it to be appointed as a defense lawyer. But for me, it’s mostly symbolic. I’m full-fledged, if that makes sense.”

“Well, it’s still exciting.”

Emelie could hear that something wasn’t right.

“How are you both?”

“Oh, you know.” Her mother started speaking more slowly. “I’ve barely seen your dad over the last three days.”

“Like before?”

“Yeah, like before. He comes crashing in in the middle of the night, but he didn’t even come home yesterday. Could you come down to see us this weekend?”

“Us?”

“Yes, us.”

“So Dad’ll be back?”

There was silence on the other end of the line.

This was what Emelie’s world had looked like during her entire childhood. Dad’s drinking benders. She hadn’t really realized it before she left home, got to university, and started thinking everything through. But she knew how he could be. How she herself could be.

They could never find out at work.

Emelie ended the call with her mother. She studied herself in the round mirror hanging on the end of the bookcase. Her dark blond hair was parted to one side, tucked behind her ears. She might not have enough makeup on today—she might not have put on any at all, now that she thought about it—but her gray eyes still looked huge. She really should go down to Jönköping on the weekend. Find her dad. Try to make him understand, once and for all.

An hour later. The door opened, and Josephine came tumbling in. They still shared an office despite the fact that Jossan was a senior associate now and should’ve been given a room of her own long ago. Maybe that was a bad sign for her roommate.

But Emelie liked sharing the office, even if Jossan could be incredibly self-absorbed and spent ten times as long talking about her manicure girl on Sibyllegatan and the sale on Net-a-Porter than about anything important. Anyway, she always practically tripped through the door, like Kramer in Seinfeld, and that alone was worth at least one laugh a day.

“Pippa,” Josephine roared once she’d closed the door. “I can see it on your face: something good’s happened. You’ve got dimples, even though you’re not laughing. Did they just call?”

Emelie nodded. Five minutes earlier, someone from the Bar had finally called to let her know that she had been accepted as a member of Sweden’s Bar Association.

She had the title now. The journey was over.

“Congratulations, Pippa. You’re a lawyer. That calls for celebrating with a glass of Bollinger at dinner.”

Josephine always called Emelie Pippa. For some reason, she thought Emelie was the spitting image of Pippa Middleton.

“You know what my favorite author always says. Happiness is something that multiplies when it’s divided.”

“So cheesy. Who said that?”

“It’s not cheesy. It’s from the world’s most insightful man: Paulo Coelho.” Jossan blinked. Then she started talking about all the books by him she’d read, how they had changed her life. They’d helped her find herself, she could be happy even during difficult times, she’d become much more aware of her spiritual self, and she could do without her materialistic lifestyle.

Emelie pointed to the three handbags hanging on a hook on the wall behind Josephine. Céline, Chanel, Fendi. “What about those?”

Josephine ran her hand over the Céline bag. It looked as though she was caressing it tenderly. “That doesn’t count as materialistic,” she said. “A woman’s got to have something to carry her stuff in.”

At seven thirty, Emelie lit a cigarette on the way to Riche. Jossan and a few of the other girls from the office were already inside the restaurant, eating moules frites and waiting to celebrate with her.

She paused. Hesitated. Maybe she didn’t have time for this. She’d been working like a madwoman. The breakup of Husgrens AB—in which the profitable parts were being sold to a Chinese industry conglomerate, and the unprofitable sections were being taken over by one of EQT’s opportunity funds—had meant fourteen-hour negotiation sessions with the Chinese for three weeks in a row. The sale of Airborne Logistics to an American industry giant meant eighteen-hour stretches in the due-diligence room, with no breaks, even on Sundays. Emelie was in charge of the other legal associates. The air in the room was always so heavy when they left that she handed out painkillers to the team every evening.

Her phone rang. Unknown number.

She answered with her first name.

“Hello, this is Detective Inspector Johan Kullman. Is this Emelie Jansson, the lawyer?”

Emelie Jansson, the lawyer. That sounded good. All the same, she wondered why a detective inspector was calling her.

“It is. What’s this about?”

“I’m calling from the custodial wing of Kronoberg Prison. We’ve got a suspect who’s requested you as his lawyer.”

“Sorry, what did you just say? A suspect has requested me as his lawyer?”

“Answer: yup.”

“At this time?”

“It’s his right to request a lawyer. And as we understand it, he’s requested you. That means it’s our responsibility to check whether you accept the task.”

“But I don’t work on criminal cases.”

“I have no idea. All I know is the suspect requested you.”

“What’s he suspected of?”

“Murder. We think he killed a man out on Värmdö last night.”

“And why does he want me?”

“That’s a little tricky to answer, I’m afraid. He’s actually more or less unconscious. He was in a car accident.”

Emelie took a final puff on her cigarette.

She’d made it to the entrance of the restaurant.

Everyone seemed to be having such a good time inside.

3

He’d been sitting in the car since five that morning. Shoving snus tobacco under his lip and chewing xylitol gum. Waiting for Fredric McLoud.

The man he was tailing hadn’t followed his usual pattern today. It was past ten now.

Teddy wondered what was going to happen, what he would have to do to finish this job—finding something big on McLoud—without getting himself into trouble. Whatever happened, he’d made up his mind: he was going to live a different life. He wasn’t going back to the slammer.

He pushed a new piece of snus under his lip. Snus and chewing gum: his new favorite combination. The snus almost too earthy otherwise. Like it needed balancing out somehow, pushing back.

Banérgatan wasn’t the world’s most interesting place on an ordinary morning in May. From five till seven, it had been deserted, like no one even lived in the grand old apartments in this part of town. Just over a year ago, he’d walked this street on another job. A dark, unpleasant start to his new life as a free man. But that felt distant somehow. Teddy had been out for almost a year and a half now.

The first people out on the street were the dog owners. Older men in hats and green wax jackets, waiting patiently as their dachshunds pissed on the nearest lamppost. Younger women in sneakers and lightweight down-filled body warmers, quickly bending down to scoop up the dog shit in their plastic bags before heading off toward Djurgården with their golden retrievers.

By quarter to eight, the men in suits and women dressed for business started to appear. They moved quickly toward their luxury cars, or else they headed off toward the city on foot.

Fifteen minutes later, it was schoolkids streaming along the pavements, aside from those who were picked up by taxi directly outside their front doors. The cars waiting for these seven-year-olds weren’t exactly Taxi Stockholm’s climate-neutral Volvos or Kurir’s environmentally certified Toyota Priuses, either. They were different cars, different companies. Teddy didn’t know their names, but he’d heard of them. These cars were booked in advance, paid for using credit cards, and ordered using the relevant app.

The family lived on the very top floor, in a pristinely renovated attic apartment more than thirty-two hundred square feet in size. Things had moved quickly for Fredric McLoud these past few years. But now, perhaps, they were on the way back down. All depending on how Teddy did his job.

At nine thirty, he finally came out. Fredric McLoud. Not wearing the suit and tie you might expect of the millionaire business leader. Instead, he was dressed in what looked like sweatpants and a polo shirt with a huge sailing brand logo on it.

Teddy noticed it immediately: Fredric’s behavior was different today. He stood still for a few seconds, just looking about, before he crossed the road and started off down Riddargatan. Every three hundred feet or so, he stopped, turned, and glanced all around him.

Teddy stepped out of the car as his surveillance object passed. He went up to the parking meter and started fiddling with his payment card as McLoud continued down the street.

Pay with your phone, EasyPark, he read on the machine. Next time, I’ll bring the fucking bike, he thought.

After a few seconds, Teddy slowly started off after him. As soon as Fredric dropped the pace, Teddy took out his phone and stopped to write a pretend text message.

This was his life now. He’d been offered the job with the Leijon law firm by one of the partners he knew from before, Magnus Hassel. The firm didn’t employ him directly—Hassel had thought that would be too much—but they had some kind of company they used for the so-called freelance jobs, Leijon Legal Services AB. The deal was actually pretty generous. They paid for a hire car and even helped him get a Visa card, despite the fact that the credit checks the bank had run must’ve shown his declared income over the past twenty years wasn’t even close to subsistence level.

His work for the company mainly consisted of so-called personal due diligences.

Fredric McLoud was one of the two founders of Superia, an online-payment service that had grown enormously over the past few years. The company had been valued at more than “a yard,” as Magnus Hassel put it, “and that’s in euros.”

Leijon’s client wanted to buy a 20 percent stake in the company. The only problem? There was talk about young Fredric McLoud being a bit of a coke fiend. And according to those same rumors, it wasn’t just a little partying here and there, no. He was snorting on a daily basis; the guy couldn’t even make it through a morning meeting without doing a couple of lines in the bathroom first.

Teddy had been tailing him for three weeks now and hadn’t seen anything odd. Either McLoud had a huge stash at home or else he got the stuff delivered to him some other way, Teddy had no idea how. The alternative was that his habit wasn’t nearly as bad as people said. Rumors were just rumors, after all, and they were often spread deliberately to ruin someone’s career.

But today he’d caught a whiff of something. He just hoped it wouldn’t all go to shit.

His surveillance target continued across Nybrogatan and on toward Birger Jarlsgatan. If McLoud had been even slightly more cautious, it might’ve been tricky for Teddy to follow him today. But as things stood, his gestures and movements were all exaggerated. He would slow down noticeably a few seconds before he stopped completely, stood stock-still, and glanced all around. As long as Teddy moved slowly, he wouldn’t bother McLoud.

There was a beggar on the corner of Nybrogatan and Riddargatan. Colorful headscarf contrasting with her dark, furrowed skin. Pieces of cardboard on the ground beneath her flowing black skirt. The woman was humming a melody: a dirge from another world. There hadn’t been as many beggars in Stockholm before Teddy was sent down; that was something new. He watched people’s eyes as they passed. They looked down, turned away. Pretended she wasn’t there.

The Leijon office was only a few blocks away. Not that Teddy needed to go in today. He didn’t have an office there, and he was happy about that. He ran these investigations more or less on his own, and it was often enough just to report to the lawyer involved by email or phone. Besides, he didn’t want to bump into Emelie Jansson.

They’d made plans to get dinner together a year or so ago, her idea. But she’d called to reschedule it, and he’d had to put their next date back, which she’d then canceled at the last minute. Their dinner plans had slipped away like shampoo down the drain.

Since it was only quarter to ten, most of the open-air cafés were empty, but there was a surprising number of people out on the street. Teddy couldn’t help but think that those who earned the most—the people who worked in this part of town—seemed to take life the easiest. The working day didn’t start before now for some of them.

Many of the people were extremely well-dressed; the men rushing past wore slim-fitting suits with slacks that looked too short, though that was probably intentional. The women were in high heels, with fluffy, well-washed hair and rose-gold Rolex watches.

He thought of his sister, Linda, and his nephew, Nikola. Teddy had gone over to her house for dinner yesterday. She’d had her hair in a bun; she’d looked tanned. Teddy wondered whether she’d started going back to the tanning beds again.

“Nikola gets out the day after tomorrow,” she’d said, “and I don’t know what I should do.”

Teddy had cut a potato he’d just peeled, added some butter. “He’s a man now. It’s not your responsibility. But he’s gonna be fine.”

“How do you know?”

“I don’t know anything. But we’ve got to believe in him. He needs our support.”

Linda had carefully cut her meat into five equal pieces. Her hands didn’t look young anymore. “He looks up to you, he wants to be like you. But the one thing I hope is that he doesn’t end up like you.”

“Like I was, you mean?”

Linda had looked down at her plate. “I don’t know what I mean,” she’d said.

Fredric McLoud stopped and went into an Espresso House.

Teddy paused. Should he follow him in and risk making him suspicious? Fredric must’ve noticed the huge man walking behind him all the way here. So far, there hadn’t been anything strange about it, but if Teddy turned up in the same café, there was no way it could be a coincidence.

He followed him in anyway. McLoud’s routine was off today. That had to mean something.

Plus, honestly, Fredric McLoud seemed so far gone that he could’ve had half of Stockholm’s plainclothes policemen creeping after him and he wouldn’t have even noticed there was anyone else on the street.

Teddy got in line by the counter. He saw Fredric sit down at a table opposite a young man with a bottle of Coca-Cola.

There was a plastic bag under the table.

Fredric shook hands with the kid. He looked young, dark hair, dark eyes. Dressed in a Windbreaker and Adidas sweatpants.

Sweatpants: Teddy remembered wearing them himself at that age. Once, Dejan had been in court for assaulting someone in a metro station. A shitty thing, but Teddy and some of the other guys had decided to go watch the trial. To support Dejan, but also for fun; they’d had nothing better to do that day. During the break, Dejan’s lawyer had come up to Teddy and said: “Get out of here, I don’t want a load of people wearing trousers like that in the public seats.”

“What d’you mean, trousers like this?” Teddy asked.

“You know, you all look alike, and the judge knows exactly what kind of guys you are. So get out of here. It won’t do your friend any good to be associated with sweatpants. Believe me.”

The ironic thing today: Fredric McLoud looked just as much a thug as the kid did.

Teddy already had his phone in his hand, the camera rolling. He pretended to be busy doing something on it, but he was really just making sure it had a clear shot of the table where Fredric and the kid were sitting. These new phones, they were pretty much magic.

Document everything: that was one of the golden rules he’d been given by Leijon. His job was all about collecting evidence. Collecting evidence without fucking things up for himself.

It only took a couple of seconds. Fredric said something. The kid nodded. Fredric took the bag from under the table, stood up, and left.

Teddy watched him through the big windows out onto the street—it was an unnatural sight, one of Stockholm’s richest thirty-seven-year-olds with a battered old supermarket bag in his hand. But he’d caught it all on film.

Teddy was still standing by the counter. It was his turn now. Macadamia nuts, raw food balls, green juices. In the past, pre-jail, the baked goods had all contained flour and sugar.

“What’ll it be?” the girl behind the counter asked.

“You have any normal buns?”

“Yeah, we’ve got sourdough.”

“Sounds too healthy.”

The girl’s eyes flashed.

Teddy turned and left.

Fredric “coke fiend” McLoud was thirty feet ahead of him, heading along Riddargatan again.

Teddy wondered why it was so important to Magnus that he do this, but the partner had been explicit. He wanted irrefutable evidence, even if it gave away that they’d been following him.

It was a bright, clear day. The sun glared in the windows. Teddy could feel his stress levels rising. He went up to a middle-aged woman who was busy jabbing at the buttons on a parking meter.

“Hi, sorry to bother you. Could you do me a favor?”

The woman turned around. Now she was holding her phone. She looked stressed—maybe she was trying to work out which app she needed to solve her problems—but she answered softly, “Of course.”

“Great, thanks. Do you see that man there?”

Teddy pointed to Fredric.

“Yes, why?”

“Just watch.”

He took out his phone again, but this time he switched on the sound recorder. Leijon had given it to him, it was a smartphone, and he’d learned how to use it much more quickly than he’d thought he would. All the same, he sometimes felt like throwing it into the water or dropping it from a balcony somewhere. Teddy refused to use the calendar function on it, but he’d given in to some of its applications: in this line of work, it was a fantastic tool.

He caught up with Fredric McLoud. Tapped him on the shoulder.

“Sorry, but I think you took my bag?”

Fredric clutched the plastic bag to his chest.

“Who are you? What’re you talking about?”

“Yeah, I lost my bag. This one’s not mine, is it?”

Fredric stared at him. His eyebrow twitched.

“Are you crazy? It’s definitely not yours.”

“Can I just have a quick look in it?”

“No way.”

Teddy moved quickly. He grabbed Fredric’s arm and reached for the plastic bag with his free hand.

Fredric raised his voice. “What the hell are you doing? Get off my bag.”

“I just want to have a look in it. There’s no problem is there?”

“Like hell there’s not. It’s my bag.”

Teddy couldn’t give up now. He needed to be in the moment—act, not analyze. JDI—just do it, like Dejan used to say.

He snatched at the bag again and pulled Fredric’s other arm to try to knock him off balance. They stumbled.

Teddy was bigger, beefier, but McLoud wasn’t some stick. And he was fighting for his career, his business, his family. His life.

Their fumbling continued.

Suddenly Teddy felt a searing pain in the hand holding the bag. He looked down. Fredric had bitten his thumb.

No. No, he couldn’t yell. Couldn’t shout. This had to work. He’d promised himself.

He could have stuck a finger into Fredric’s eye. Hit him square in the nose. Grabbed his Adam’s apple and just ripped it out. But instead, he pushed Fredric’s head, pressed his hand against his cheek, tried to force him into submission.

Eventually, Fredric let go of his thumb. Teddy saw blood on the man’s teeth.

He needed to take control now. Calm the situation. He was standing close to McLoud.

The woman was shouting something in the background. “Stop this now. I’ve called the police.”

Teddy was panting. “You heard her. I’m pretty sure you don’t want the police to come snooping around that bag of yours. Just let me have a look.”

Dilation. Panic in McLoud’s eyes. The guy understood.

Too late for Teddy. McLoud had started to run.

Teddy had thought it would all be over by now. He rushed after him.

Along Riddargatan. To the left, onto Artillerigatan.

Uphill. McLoud had long legs. And Teddy knew he saw his personal trainer in the fancy Grand Hôtel gym three times a week.

Teddy could feel how heavy he was.

Up the hill. Army museum to the left. A home electronics shop to the right.

On to Storgatan. He wouldn’t be able to make it much farther.

People were staring at them. Some of them were shouting.

Then, all of a sudden, Teddy couldn’t see him anymore.

Where the fuck had Fredric McLoud gone?

He saw a police car farther down the street.

Shit, shit, shit. It couldn’t end this way.

He slowed down. Swedish Enterprise’s offices to his left. A men’s clothing shop to the right. The first thing the cops would home in on was anyone running. He tried to catch his breath. Analyze the situation.

Where had Fredric McLoud gone? He had to be here somewhere, just a few feet away. He couldn’t just disappear.

The police car was only a hundred or so feet behind Teddy now. It was crawling forward.

He had to do something.

Fifty feet.

Teddy looked both ways. People had seen him running; they could point him out. He had no other choice. So, calmly and quietly, he made a decision: he entered the clothing shop.

Tweed jackets, corduroy trousers, hunting caps. The place didn’t exactly radiate a spring feeling. He moved deeper into the shop—still completely focused on what was going on behind him.

The police car: he hoped it had rolled on by.

And then he almost burst out laughing. In front of him, by the suits, Fredric McLoud was standing with his back to him. He was still clutching his plastic bag. He’d clearly had the same idea as Teddy.

Teddy tapped him on the shoulder and said: “I think it’s gone. If you and I can stay calm, anyway.”

McLoud’s face was no longer panic-stricken. He seemed to be close to tears.

“Who are you? Why are you doing this?”

Teddy said: “Bound by professional secrecy, I’m afraid.”

4

When the day’s conversation group ended, Nikola was already outside the classroom. That was him in a nutshell. Always first out. One image in his mind from all the classes of his youth: the empty hallway, the graffiti-covered lockers, the silence before the rest of the class came storming out seconds later. Nikola: always too much energy to calmly pack up his things, chitchat with his friends for a few minutes. Always stressed out by some invisible force, desperate for a nanosecond of quiet hallway. A slice of tranquillity.

But that was long gone. He hadn’t spent much time at school these past few years.

Linda and the director called his behavior mild ADHD. Not that Nikola took Ritalin or self-medicated with junk like some of the other guys did. They just wanted to stick a label on the energy that burned beneath the gold cross on his chest. The gold cross he’d gotten from Teddy, before he’d gone in to do his eight years.

But all that dick sucking faded into the background today. Life: fucking sweeeet. Today was the day. The last day.

Chamon was coming to pick him up and take him away from this shit hole.

One last little piece of crap: before Nicko could leave, he had to have a final chat with the director.

Somehow, Anders Sanchez Salazar managed to get his room to look exactly the same every time Nikola was forced to go there.

It wasn’t just that the two visitors’ chairs were pushed in under the front of the desk in the same way, or that the curtains were half drawn like they had been the last time. Everything was an exact copy. The papers on the desk, the pencil case behind the computer screen, the pictures of his kids. Everything was in the same place. Even the coffee cup with the Hammarby logo on it was on the same corner of the desk as the last time he was there.

The only thing that had changed was the color of Anders’s cardigan. Bright red today. It had been burgundy last time.

“So, Nikola. How’s it feel?”

Nikola tried to stop himself from smiling too widely.

“Really good, actually.”

“I know it can be a bit daunting to leave Spillersboda when you’ve been here as long as you have. What do you think?”

Nicko had to try even harder to stop himself from laughing.

“Yeah,” he said. “A bit.”

“But I’m sure everything’s going to be fine. You’re going to be living with your mother, aren’t you?”

“Yeah, she said she’d let me in. I promised her I’ll get my act together.”

“Are things better between you now?”

“Yeah, definitely. She’s the best.”

Years of contact with nags from social services, with head teachers, welfare officers, and cops—Nicko: the expert of all experts. It wasn’t hard to work out what they wanted to hear. The tricky thing was making it sound trustworthy. The only true part was that he really did think Linda was the best.

“One piece of advice, Nikola,” said Anders. “Stay away from your old pals. I’m sure they’re good guys, it’s not that, but it’ll just end in trouble. A load of grief, like you all say.”

Chamon fiddled with his rosary. It was less than three months since he’d passed his driving test, but the Audi he was driving looked newer than that. The twenty-inch rims were as shiny as Nicko’s gold cross had been when it was new. He knew the A7 belonged to his friend’s cousin, but when you came somewhere like Spillersboda, you wanted to show you lived a different life.

“Meksthina?”

Nikola grinned and pushed a piece of snus under his lip. He answered in the same language. “Abri, let’s go, man. Do a Zlatan.”

To most of them, he was just Nicko, but the brothers sometimes called him Bible Man, because they thought he spoke Syriac like people did in the old days. They were impressed all the same. Nikola was the only non-Syrian or Assyrian guy they knew who spoke their language. But was it really so surprising? He’d grown up with them. And like his granddad always said, when in Rome . . .

“What d’you mean, do a Zlatan?”

“Hat trick, man. I scored three joints from a guy in here. He owed me. We’ll smoke ’em all when we get home.”

“Too funny, bro. You gonna get in on the thing soon?”

Nikola knew what he was talking about. Yusuf’s question. The thing.

Directly for Isak. Real shit.

They started heading for the gates.

The guys in the yard moved aside as Nikola and Chamon passed.

“So, you been getting any? I didn’t even see you last time you were out.”

“Hell yeah, been getting more ass than the toilet seats in the ladies’ room at the Strip.”

Chamon roared with laughter. “Walla.”

They opened the gates and stepped out. The spring sunshine was strong today. The leaves on the trees outside were pale green. They looked a bit like marijuana leaves, only bigger. Sandra had said they were chestnuts.

“Shit, I should probably be Instagramming those leaves to celebrate. Last time I’m gonna set foot here, and I’ve been staring at those trees from my window for a year.”

“You’ve got Instagram?” Chamon asked.

Before he had time to answer, they heard a voice behind them. “Nikola, could you come back a minute?”

They turned around. It was Sandra. She was standing by the gates, her face beaming. Weird: she was actually pretty cute.

“What for?” asked Nikola.

“I just need to talk to you about one last thing. It’d be great if you had time.”

“I’m done here, Anders signed me out fifteen minutes ago. I’m in charge of myself now.”

“I know, you’re right. But this is important.”

Nikola glanced at Chamon. “She’s such a fucking pain, man.”

“She been cool or was she a bitch?”

“Today?”

“No, while you were inside.”

“She’s all right, really. She wants the best for you, you know what they’re like . . .”

“I get it, so you can show her some respect. You’re a free man. Just go see what she wants, then we’ll get outta here.”

Sandra walked ahead of him toward the main building. Nikola followed her.

The moment he stepped inside, he knew something wasn’t right. He couldn’t say what, it was just a strong feeling that came over him. He followed Sandra into one of the so-called supervisor rooms anyway.

It was calmer and cleaner inside than it was in the inmates’ rooms. Some kind of informative poster pinned up on the wall: Student integrity online. Sign up for our Internet Days now!

“Are you going to continue with your work experience place now, do you think?” Sandra asked.

“Dunno.”

“It was electricity and telecommunications you were working with, right?”

“Yeah.”

“And it’s almost summer. Good, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“How does it feel?”

“What?”

What the hell was this? Sandra trying to make small talk like they were friends or something—he was done with this place, for God’s sake. He turned to leave.

Then he understood. A side door opened, and Simon cunting Murray came in.

Sandra must’ve known. Simon Murray was a cop. The plainclothes one who’d always been after Nikola and the boys. Who stopped their cars and paid visits to their parents. Who always turned up like some kind of genie outside Chamon’s house, at the club, at O’Learys. He was a part of Project Hippogriff—the joint action force in the southern suburbs, aimed at creating a safer city—as they called that shit.