Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Stockholm Noir

- Sprache: Englisch

Now a major Swedish TV series, with plans to bring it to UK audiences. For decades, a secret network in Stockholm has been exploiting young girls, ruthlessly eliminating anyone who threatens to reveal their secret. As oddly paired duo Teddy and Emelie - the thug and the lawyer - investigate, the terrifying noose tightens. The police force has established a special team to find out just who's involved in the network, but can't seem to get close enough. And who is it that's trying to silence Teddy and Emelie, using any means necessary?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 769

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

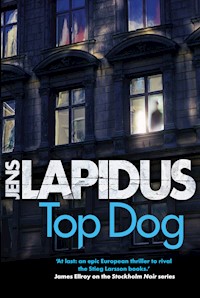

JENS LAPIDUS

TOP DOG

Jens Lapidus is a criminal defense lawyer who represents some of Sweden’s most notorious underworld criminals. He is the author of the Stockholm Noir trilogy, three of the bestselling Swedish novels of this past decade: Easy Money, Never Fuck Up, and Life Deluxe. He lives in Stockholm with his wife.

ALSO BY JENS LAPIDUS

Easy Money

Never Fuck Up

Life Deluxe

Stockholm Delete

First published in the United States in 2018 by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in Sweden as Top dogg by Wahlström & Widstrand, Stockholm, in 2017.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jens Lapidus, 2017

English translation copyright © Alice Menzies, 2018

The moral right of Jens Lapidus to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 179 4

Export trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 177 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 178 7

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

SWEDISH WOMEN’S WEEKLYEXCLUSIVE MINGLE AT BUCHARDS EXHIBITION

CoolArt and Buchards threw an exclusive launch party last night, in celebration of their unique art. The event saw Prince Carl Philip and his graphic designer friend Joakim Andersson mingling alongside Stockholm society and the big names of the art world.

Our reporter also spotted a couple of newcomers to the Stockholm collectors’ scene: youthful financier Hugo Pederson and his beautiful wife, Louise. The stylish pair are said to have a keen interest in art, and sources tell us that they have built up a sizable collection of contemporary pieces despite having only been collecting for two years.

“I’ve always loved the fragile, the complex,” Mr. Pederson cheerily told our reporter.

Mr. Pederson works for investment firm Fortem, and has rapidly become a great patron of a number of artists.

“If you’re lucky enough to earn a bit of money, you also have to give back,” he continued, heading off to mingle alongside his equally engaged wife.

Johan W. Lindvall, 2007

Prologue

Adan dragged the aluminum ladder over to the back of the building and peered up at the balcony. The apartment was on Nystadsgatan: first floor—it shouldn’t be too hard to unfold the ladder, lean it against the balcony, and climb up. But still, fuck—he felt like he was about to shit himself. Genuinely. He could just see it: him at the very top of the bastard ladder with a brown stain on his ass.

He had actually stopped doing jobs like this. He was nineteen now and too old for break-ins: it was the kind of thing they used to do at the end of high school. Plus: it was beneath him now. But what was he meant to do? If Surri told you to do something, you did it.

They had known each other since kindergarten, lived on the same block, played on the same teams—their fathers had even been neighbors back in the old country. “We were like everyone else in Bakool. We didn’t care about one another more than we needed to,” Adan’s old man used to say. “But everyone here thinks we’re like family, like we’re the same person.”

His father was both right and wrong: Surri was a brother. But he still acted like a dick.

Adan could feel the chill of the ladder through his gripper gloves. Gloves: he had kept that part of the routine from before—his prints were guaranteed to be saved in a database somewhere. He braced himself; there was a lot of him to haul over the railing: he had to weigh at least 240 pounds. Still, the screwdriver was light in his hand, and the grip felt comfortable—as though his fingers had actually been longing to use it, despite his living a completely ordinary life these days. Drove a delivery van for his dad’s boss, ate popcorn and watched Luke Cage and Fauda with his girl at night. It was just that two weeks earlier, he had been asked if he wanted to earn a little extra dough. Nothing illegal, just a one-day job for old times’ sake. You were crazy if you said no to that kind of thing.

It was all those German bastards’ fault. What Surri had wanted was for Adan to travel down to Hamburg and pick up one of the new 7 Series BMWs. It was a done deal: you could get a 730d for under 100,000 euros there, then sell it without any trouble for 150,000 back in Sweden. The only problem: you couldn’t register too many cars to yourself in any given year, otherwise the tax authorities would come sniffing. And that was where Adan came in.

He had taken the train down to the southern tip of Denmark; a one-way ticket was 599 kronor, and he had spent the entire journey listening to Spotify on his new Beats headphones, keeping a tight grip on the fanny pack Surri had given him, and staring out of the window. A million kronor in euro notes weighed almost nothing. He had never spent so long on a train before, but it was actually pretty sweet. He never got bored of watching the scenery outside. It flew by: frosty fields, wooded areas, and small towns where people seemed to collect rusty wrecks and old planks of wood. He wondered how they made a living.

He’d had no trouble finding the car place, signing the documents, and negotiating with the salesman, who even spoke a bit of Arabic—it wasn’t Adan’s language, but he knew enough to be able to say a few friendly phrases. It felt sweet to sink back in the black leather seat, start the engine, and cruise back to Sweden. He drove different pickups every day, but never BMWs. This car didn’t just look like it had class—you could feel the quality in the details, too. The smell of leather, the feeling when he ran his fingers over the dashboard, the weight of the doors, and the faint, comforting sound when they closed. He had thought about Surri, the guy did everything with style—even his balaclavas came from sick French designers. One day, Adan might even be able to afford a car like this. But, right then, his plan had been to drive all evening and night. He wanted to get the BMW home without having to check in to a motel.

It was on the highway outside of Jönköping that he first heard it: a hollow scraping noise that definitely didn’t sound good. He had pulled over two miles later. Climbed out, inspected everything, but he couldn’t see a thing. The sound had returned the minute he pulled away. After another twelve or so miles, a warning light had come on. “Brake Fault.” What did that mean? Shit—he didn’t know if he could even keep driving. He had slowed down, causing a line of traffic behind him; he was going forty in the seventy-five lane. The car sounded terrible. Another five or so miles later, he had pulled into a gas station and asked if the assistant could come out and check the car. The kid had spots all over his face and looked like he was five years younger than Adan, but he had immediately started shining a flashlight at the rims of the tires.

“Looks like your brake pads are pretty much gone,” he had said. “You can’t drive another inch in this car. Shame with such a sick ride, by the way.”

That had been the end of the upside: Adan had had to pay a recovery van to tow the car to the next garage. It had taken five weeks to fix and cost forty grand. But there was also a risk it was pulling to one side, they said. Adan had called the seller in Germany and yelled at him, but the guy had pretended he didn’t even speak English. In the end, Surri had a valuation on the piece of crap car: he wouldn’t even get six hundred thousand for it.

“How could you be so thick not to even check the car before you signed?”

The lock on the balcony door gave way with a click and Adan pushed it open. Surri had been clear: “The cops are keeping our guy who rented the place in custody, but they haven’t found the shit there. So if you break in and find what’s mine, we can write off half your debt. You know how much I blew on that car.”

Adan had squirmed. “Is anyone living there?”

“Fuck that. There won’t be anyone home tomorrow night, either way.”

Adan thought back to one day in the yard when they were younger. Surri had fallen from the jungle gym, dropped like a little rock and cut his knee. To them, it seemed like a river of blood had come flooding out, and the cut was full of gravel. His friend wouldn’t stop crying. “I’ll help you. C’mon, let’s go to my place, I think my dad’s there,” Adan had said in as gentle a voice as he could. They were six at the time, and Adan knew that his father could mend Surri’s knee. Sure enough, he had—his father had cleaned the wound and applied the biggest Band-Aid they had ever seen. As they drank chocolate milk, ate cookies, and watched Toy Story on DVD afterward, Surri had said: “Your dad’s better at that than mine.”

It was a two-bedroom apartment. Adan switched on the light in what had to be the living room and saw a green sofa, a glass-topped coffee table, and a bookcase. There was also what looked like a projector of some kind. In both bedrooms, there were narrow, unmade beds. People had to be living there—why else would there be newspapers on the coffee table and a T-shirt hanging over the back of a chair?

At the same time, the place was also barely furnished, so maybe they just slept over here every now and then. He picked up the garbage can in the kitchen, peered down at an empty milk carton, and caught the scent of something he definitely recognized: stubbedout weed.

He went through the kitchen cabinets and the fridge. The person or persons living there had plenty of chips and sour cream, but no normal food. He peered into the oven and the dishwasher, got down onto the floor and shone his flashlight beneath the sink and behind the fridge. It was dusty.

People could be imaginative sometimes, but he didn’t find a thing. He lifted the cushions from the sofa, ran his hand beneath the sheets and the mattresses in the beds. There was a bag on the floor in one of the bedrooms, and he rifled through it—spotted a few more T-shirts, four pairs of boxers, and some socks. He climbed onto the coffee table and shone his flashlight into the air vent in the wall. Nothing.

He couldn’t see a thing.

Back in the living room. Adan got down onto all fours and peered beneath the sofa, shone the flashlight behind the bookcase.

The guy who rented the place before these people must have screwed Surri over—there was nothing here, or maybe the cops had found it after all. It wasn’t really Adan’s problem anymore. Not that Surri would see it that way.

And then he heard something. A noise from the hallway.

No, it was in the stairwell, on the other side of the door. He could hear voices out there.

Before Adan had time to think, he heard the key rattling in the lock. Shit—someone was on their way into the apartment. He turned out the lights in the living room.

He could hear people talking in the hallway now. Two voices, a girl’s and a guy’s. Maybe he should just jump out and beat them up, whoever they were. But no—he wasn’t like Surri. He wasn’t a tough guy.

He crawled behind the sofa.

The voices grew clearer. The girl was talking about someone called Billie. The guy mumbled something about a party. “Almost party time.”

Adan lay perfectly still, trying to keep calm and quiet. He should go back to Hamburg and kill that BMW salesman with his own bare hands—this was all his fault.

Then he heard a door close. It sounded like it might have been the bathroom door, judging by the distance. Was this his chance? He could hear only the girl’s voice now; she was humming some tune. The guy was probably in the toilet. It sounded like the girl had come into the living room. Then silence. Adan wasn’t even breathing, just trying to listen. The padding of feet. Puffing sounds. Then more footsteps, out, toward one of the bedrooms.

Now.

He got up: the living room was empty. He took two long strides toward the balcony door. He wasn’t thinking, wasn’t reflecting. Just acting. He tore open the door. Didn’t look back. Stepped out onto the balcony. Closed the door behind him. Sucked in the fresh air.

He jumped over the railing.

He threw himself down. No, he fell.

Like Surri from the jungle gym.

The darkness felt safe, but it was far too cold out. His gloves were as thin as paper.

Adan leaned against the tree. He was trying not to put any weight on his right foot, which he had really hurt in the fall—the bastard might even be broken. All the same, he didn’t want to leave. The ladder was lying on the ground in front of him: he had dragged it behind him as he limped away over the snow. Surri would go crazy when he told him he hadn’t found anything. Still: it had to have been Surri’s own guy who’d screwed him over. Adan had searched everywhere.

He had been standing here for four hours now. Just waiting. Hoping the pain in his foot would go away. The lights were on in the apartment. Strange colors lit up the walls, and the music poured out from the balcony doors, which opened every now and then. There were so many people inside—he could see them through the windows like blurry backup dancers on some televised talent show.

At some point tonight, the idiots in there would have to leave, or at least go to bed. At some point, the chips and dip would run out. Then he would put the ladder back in place and climb up onto the balcony again. Search the place one last time.

He wouldn’t be able to stand here all night—his foot was in too much pain—but he could hold out a while longer.

He wasn’t really a warrior.

But he could wait.

There were nineteen people in the little living room, but they had invited at least as many more. Roksana really wanted the place to be packed tonight—for her and Z’s housewarming. She hoped people would think it was a good opportunity to party. They would come, wouldn’t they?

Young Thug tunes thundered out of the sound system she had borrowed from Billie—and which Z had linked up to SoundCloud on his phone. Thuggy delivered—his listless, droning voice in a melodious riddim rap. It was a full-asbody experience, a dive into a warm, swirling, glittering sea of styles and sounds. Roksana glanced around the room again: Did people like the tunes? Were they having fun? Was the atmosphere good?

People had brought their own drinks. Bottles of sparkling wine lined up on the coffee table. Roksana had explicitly asked for it in her Messenger invite: Bring bubbles! Roksana & Z will supply the tunes, party, and nibbles. She hoped it hadn’t sounded too forward.

The nibbles consisted of peanuts and chips, but Roksana had dribbled some truffle oil into the sour cream—and everyone said it was the best dip they had ever tasted. Still, the food wasn’t exactly the main event—the focus was on the party, and the party was fueled by the music. The sound system, the choice of songs, the mix. Z had even managed to get ahold of a smoke machine and a mini-laser show. They hadn’t had time to put up any pictures or posters, so it was perfect, the best use for a white wall. The ironic smoke hung around the sofa like a cloud, and Roksana thought it felt like she was in a club, a super exclusive one. The only difference was that they were missing a DJ booth and that the people still arriving would have to wade through a hallway full of Roshe Runs and retro-inspired Vans. It was Z who had insisted on the no-shoe policy. “If we’re going to do this, we need to limit the amount of cleaning we have to do afterward. Because I suck at cleaning. Have I ever mentioned that?”

Roksana didn’t know what Z had or hadn’t said—they hadn’t exactly planned to move in together. Still, it should work out. Z was a good guy.

She checked Instagram and Snapchat to see whether anyone had uploaded anything from the party. But no, so far their event hadn’t made it into that territory. Please, people, she thought, you like the party, don’t you? Can’t you just dance, even a little bit, a few of you, at least? And take some photos.

The apartment was pretty big, 560 square feet, but it was on Nystadsgatan in Akalla, which was pretty far out from central Stockholm and from Södertörn University, where she was studying. But Roksana hadn’t had any other choice. She had been renting a room from Billie before, on Verkstadsgatan in Hornstull, until Billie had decided to become polyamorous and have three of her partners living there at the same time. Z had suggested that they rename that part of town Whore-nstull. But for Roksana, it wasn’t a joke; there just hadn’t been room for her—plus, she couldn’t cope with one of the guys playing cheesy Swedish pop on Billie’s stereo all day, not even ironically. As luck would have it, Z had been kicked out of his sublet that same week. He had spent three days sleeping on his gran’s sofa and had been an inch away from a serious mental breakdown.

Roksana was standing between Z and Billie. All around her, the guests were mingling. A few were rocking gently in time with the music. She didn’t want to watch them too openly—it would be too obvious. She checked Instagram and Snapchat again. Maybe they thought she was boring, just sticking with her besties; maybe her besties thought she was beige for just sticking with them.

She had her hair up in honor of the evening, and she was wearing her new silver Birkenstocks. Other than that, she was wearing her usual blue jeans and a white T-shirt she had found at her mom and dad’s place. Billie moaned about it sometimes, but Roksana stuck to her usual look; her style icons were George Costanza and practically everyone from Beverly Hills, 90210. The whole thing was a middle finger to trends and fashion ideals.

Billie was in a great mood—that was a good sign. She was wearing Adidas pants, a loose long-sleeved T-shirt, a choker, and a soft Gucci cap on top of her pink hair. She had even dyed her underarm hair pink—“To celebrate you guys,” she claimed. It was hard to believe that she would be starting a law degree in just a few days’ time. Roksana was glad that Billie had left all her boyfriends and girlfriends at home—she was always more relaxed without them. She was Roksana’s oldest and probably closest friend, but after their recent problems, she didn’t really know quite where they stood.

Billie pulled out a carton of cigarettes. “What’s the deal here? Do I have to go out to the balcony, or is it OK if I smoke in here?”

Z looked up again. “Hell no. The smoke gets into the curtains and bedsheets. Roksy and I have talked about this.”

Billie rolled her eyes. “But you don’t even have any curtains.”

Z was firm. “Makes no difference. Smoking indoors isn’t cool.”

“Is this going to be some kind of clean living place or what?”

Roksana laughed. “Yeah, only plant-based, organic food. Forks over knives, you know the drill. And no plastic sets foot inside the front door.”

Z pulled out a ziplock bag and a pack of OCB Slims.

“Anyone want their own joint? I’ve got plenty.” He held up the bag. “You know there’s a golden rule when it comes to marijuana. Keep sativa and indica separate. Both are subspecies of cannabis, but the plants look completely different, different thicknesses of leaves and all that, but who cares. The important thing is the effect: it’s like night and day. Indica’s your regular couch stoner variety. Like, it gives the right high for someone who wants a Play-Station and chill feeling. But this is a twenty-four-month sativa, the Châteauneuf-du-Pape of weed. It doesn’t get any better than this.”

Z carefully separated the grass on the rolling paper. “You smoke this, you get high. Then you smoke some more and get even higher. There’s no ceiling, I swear.”

That was all beginner’s bullshit. The difference between sativa and indica wasn’t always clear, but Z loved putting words to things, chatting away. It was who he was: he couldn’t just keep up with the world—he had to be able to describe what was going on, narrow it down, understand it in terms of categories and structures. Sometimes, it felt more like a competition.

Roksana took the joint Z held out to her and took a deep puff. “Have you finished mansplaining yet?”

They laughed, Z too. “You know what I’m like,” he said.

Z was nice, in his own special way: he saw patriarchal structures as clearly as he saw the principles of weed; he didn’t just understand society’s patterns, he was also aware of his own position in the power hierarchy. A man who explained things to women. A man who always knew what was what. A man who began 90 percent of his remarks with the words “So, it’s like this . . .”

The hours passed. Erik Lundin mixed nicely with Lil B in a sweet fade to Rihanna—a bit unexpected, but shiiit, she was good—and then something completely different that only Z knew about: apparently their name was Hubbabubbaklubb. People were bouncing on the floor, free spirit dancing in the corners, bobbing in time with the music. Z’s little laser show beamed geometric shapes onto the walls. There were empty plastic glasses and broken chips all over the table. Rizla papers and wine bottles strewn on every other surface. She might even have seen a rolled-up banknote—people were too obvious sometimes; it wasn’t cool.

They had to be having fun now? Roksana checked her phone for the two hundredth time. The only thing that had been uploaded was a screenshot of Z’s playlist, accompanied by a cigarette emoji and the words smoke w every day.

Roksana had warned the neighbors, so they should be okay, she and Z weren’t exactly planning to have parties like this every weekend. Plus, for some reason, she got the impression that the guy they were subletting the place from, David, didn’t care all that much. So long as he got his money, he was happy, though the strong smell of weed that was probably lingering in the stairwell might raise questions. One of the neighbors had told her that the guy who lived in the apartment before them had caught the police’s attention. They had apparently arrested him and raided the place a few weeks earlier, but then they had handed the apartment back over to David. Roksana didn’t care; David had said they could live there for as long as they wanted, so she didn’t care who had been in the apartment before, or what they’d used it for. The important thing was that people thought she and Z were doing things right now.

That it was a good start to her mini collective with him. A good start to the term.

Her friends had gone. Too early, it felt like. Roksana tried to stop the thoughts swirling through her head: Had she been too much of a cliché when she told them she was thinking of studying in Berlin? Hadn’t she been nice enough?

The living room looked like a war zone. The rug in the kitchen was damp; there was weed on the windowsill. She wondered how Z would cope with the cleaning afterward.

Billie said: “Shit, everyone just disappeared, including my ride. Guess a lot of them wanted to see Ida Engberg.”

Z was on the sofa. “Ida Engberg, she’s the absolute bomb. Maybe we should go, too?” Z was so high on his so-called twenty-four-month sativa that he probably couldn’t even stand up straight.

“We need to clean and air this place. But you go if you want. It’s cool with me,” said Roksana.

Billie’s pupils were as big as the cosmos. “I can help you clean up the worst of it.”

“How were you planning to get home, then? Taxi?”

“Nope.”

“First metro into town?”

“Nope.”

“Kayak?”

Billie laughed.

Roksana opened the balcony doors wide. She didn’t feel drunk anymore, and only a little bit high, but the cool, fresh air still came as a surprise—it was like her mind had been rinsed with mineral water. She peered out at the shadowy trees: the apartment was on the first floor—it wasn’t all that far to the ground. She could make out a thin dusting of snow down there, but right beneath the balcony it looked like someone had torn up the grass, and she could see footsteps leading away in the darkness.

Billie could get home however she wanted; it wasn’t Roksana’s problem.

“I saw that you had a fold-up bed in the closet. Can I sleep here?”

Roksana turned around. The room really was a mess; someone had knocked over a bong, and the water had seeped out beneath the coffee table—but she couldn’t stop her heart from skipping a beat: Billie wanted to stay over.

“Don’t you have to get home to Fia, Pia, Cia, Olle, and whatever they’re called?”

“You sound a bit heteronormative right now and fascist.”

“I didn’t mean it like that. But you did actually kick me out of your place. And now you want to sleep here.”

“We have to question the prevailing norms, and that also applies to the way we speak. Words are authoritarian instruments in the gender power balance . . .” Billie grinned at herself. Her mouth was crooked; it always had been. “But I’m so sleepy. And it’s ages since we had breakfast together.”

They opened the closet door. A musty smell hit Roksana. There wasn’t a light inside, but Z used the flashlight on his phone to shine a beam of light over a cardigan and a denim jacket that Roksana had hung up. He was okay with Billie staying over, too.

There was something off about the closet. Roksana didn’t know what it was, but it gave her bad vibes.

“Can I borrow your phone?” She shone the light onto the wall. The closet was almost empty, with nothing but the bed, her two pieces of clothing, and a few abandoned hangers dangling from the clothes rail inside. The smell wasn’t actually musty; it was more like old wood and stale air. But she suddenly realized why the space had given her a bad feeling—and it wasn’t the booze or the weed she had smoked. No, something wasn’t right. The bathroom had to be on the other side of the wall, but, if that was the case, the closet should have been bigger. The angles were all wrong. The architect must’ve been tripping. Something was built weirdly in there.

And then she started to knock. Even now, she realized that she wouldn’t have done it if she hadn’t had the cocktail of drink and drugs that she’d had earlier. She knocked on the inner wall. She knocked everywhere, at the bottom, in the middle, higher up—like she was searching for hidden treasure somewhere. Roksana stood on her tiptoes and felt the top of the plywood sheet behind the clothes rail. She managed to push her fingers in above it. It creaked.

“Z, help me with this. I think this wall is loose.”

Z staggered into the closet. Billie watched them from outside. Z: high and tall.

“Pull it a bit,” said Roksana.

Z yanked the wooden sheet. It moved. The entire wall came loose and fell down on top of them.

Roksana managed to raise her hands in time; somehow she had been expecting that very thing to happen. The board was thin and light, not even half an inch thick.

“What the?” Z groaned. It had hit him on the head.

They peered into the space that had opened up in front of them: narrow, maybe five square feet in total. There were two boxes inside.

Roksana suddenly felt focused, sober: the fresh air from the open balcony doors had made it all the way inside. Cool. Clarifying. What was this hidden space?

She bent down and picked up the box closest to her, which was roughly eleven by eleven inches wide.

Z was on his feet now. “Is this some kind of self-storage place or what?”

She placed the box on the living room floor.

It was easier to see in there. The cardboard box wasn’t taped shut.

Z leaned forward. Billie did, too. Roksana bent down and folded back the flaps.

They all stared at the contents.

What the fuck?

1

The only good thing about this meeting was that it was with the same caseworker who had helped Teddy when he was first released. Her name was Isa, and she looked just like she had when they first met: Still around forty, still dressed like some kind of hybrid bohemian Södermalm woman and blingy Östermalm lady. Still wearing brightly colored scarves and weird wrist warmers alongside small diamond earrings, which weren’t actually that small.

“Hi, Teddy! It’s been a while,” said Isa. Small dimples appeared on her cheeks when she smiled. For some reason, Teddy liked her, even though her only role was to put him to work.

“Yeah, time flies,” he said, trying to seem friendly in return. The whole thing was really just embarrassing.

When he first got out of prison, he hadn’t thought he would need to sit here. And certainly not several years later. He had thought he would come out to a different Sweden, that he would be on a different level. He had been motivated, ready to work hard and to give up his time. He really had changed: he was ready to take the hard route, to leave all the crap behind him. But being ready was one thing—actually changing was another. Reality had quickly caught up with him. There was an eight-year black hole in his CV, and by now he had almost become accustomed to people’s suspicion. Though only almost.

“Well, let’s go over how the past few years have been, job-wise,” Isa suggested.

“Where do you want to start?”

“I know you found a job at a law firm?”

Teddy wanted to keep this brief. “Yeah, I took a few assignments as a special investigator for a firm called Leijon.”

“Special investigator, what does that mean?”

“It’s kind of hard to explain, but the partner in charge, Magnus Hassel, he called me a fixer.”

Teddy thought back to how many of those jobs had led to violence, and how he had risked becoming the Teddy he no longer wanted to be. He hadn’t worked for the firm for more than a year now, ever since the whole Mats Emanuelsson case.

Isa asked a few questions about wages, work experience, and whether he had taken any training courses. “And after the law firm?” she wondered. “What did you do then?”

“Since then it’s been tricky. I’ve taken some Krami courses.”

Isa looked down at her papers. He knew she wouldn’t just be able to see that he had taken all of the guidance courses and group activities run by Krami, but also that he had completed at least five practical placements. None of them had led to a permanent position.

Krami was an initiative run by the Public Employment Service and the prison authorities, aiming to help guys like him—people with a so-called criminal history—find and, above all, hold down a job. He didn’t know why it never worked out for him.

Isa talked about guidance courses and work plans. Her desk was made of pale wood. The floor was linoleum, the walls covered in white textured paper, and the chairs felt plastic. Behind her, there was a glass panel through which Teddy could see other employment officers and his own reflection. He was tall and always felt like his hair was invisible somehow: ash blond, shortish—or maybe it was mid-length.

With the exception of Isa’s earrings, everything in the room reminded him of prison. It wasn’t a personal room, it wasn’t Isa’s own office, it was a meeting cell, a place that looked in to the employment service but not out onto reality.

Though maybe Teddy did know what his problem was. After all those years in prison and his subsequent years of freedom, he still didn’t know anyone but the people he had met inside and those he had known before he was sent down, people who belonged to his old life. He could count the number of people he was close to on one hand: his sister, Linda, and her son, Nikola. Dejan, from the past. Tagg and Loke, from his corridor in Hall Prison. Those were the people he felt comfortable around. It was in their company that he could be himself. Then there was Emelie, of course, but he didn’t want to think about her right now. In any case, none of them could offer him a job, other than possibly Dejan. But that work would hardly contribute any tax to the Swedish state. In fact, there was a risk it would actually lead to increased costs for the country—in the form of a greater burden on the law enforcement agencies investigating whatever Dejan was up to.

Maybe he should just accept his predicament: realize that he didn’t fit in. Teddy would never be a part of the Sweden that he had longed for while he was inside, ever the outsider. But that wasn’t the same thing as saying he wanted to be a criminal again.

“Are you listening, Teddy? You have to listen, otherwise I can’t help you.”

Teddy stretched out his legs beneath the table. They had almost gone stiff from sitting still for so long. “Sorry. I was just thinking about a friend who might be able to help me find a job.”

It was a long shot. But what was he meant to do? None of the courses, placements, or group seminars had led anywhere. Dejan was bound to be able to help him, for old times’ sake. Isa tapped away at the keyboard as Teddy told her about his friend’s construction company. Then she cocked her head and gave him a serious look.

“I’m sorry, Teddy, but I think it could be tricky with your friend. I don’t want to sound judgmental, but his firm has a very modest turnover, and he hasn’t declared any income for the past ten years. I don’t think he can offer you a real job. Not a job that I can approve, anyway.”

Isa was right.

But she was also wrong.

2

It was six in the morning, and the crazy thing was that Nikola didn’t even feel grumpy. George Samuel, his boss, had a particular way of smiling, which meant that his entire face crumpled up around his eyes. Nikola wondered whether George could even see when he smiled.

“Morning, Nicko, know what we’re doing today?” he said as Nikola stepped into the cramped office.

Nikola put on his tool belt. “Yep. We’re starting our biggest ever job. You haven’t talked about anything else for a week.”

They walked out to the van together: George Samuel Electrical in elaborate script on both sides. His tool belt jangled. Nikola didn’t have his own ride, which was why he always met his boss at work and traveled with him to their jobs. Plus, it gave them a good opportunity to chat.

It was his mother, Linda, who had found him this placement with George Samuel. And now Nikola worked like any other Swede: five days a week. Up with the first radio broadcasts, lunch at eleven thirty on the dot, then back home before it even got dark in winter. Sometimes, he slept for an hour before dinner, just so he could manage to stay up past nine.

An unfinished shopping center rose up out of nothing in Flemingsberg, tucked between the train tracks and the court—like someone had buried an enormous concrete egg there, and it had only just started to hatch. It really was a huge job. George Samuel wasn’t the only electrician who had been contracted, but for him and his apprentice, it meant ten months of full-time work all the same. A guaranteed customer for almost a year—that was invaluable, Nikola knew.

They stood side by side: worked as a team. Single-phase, three-phase, junction boxes. Cables, fuses, and amps. Nikola’s technical vocabulary had swollen so much that he knew more electrical words than he did slang terms for drugs. Sometimes, it felt like his job meant more to him than the rest of his life put together, but that was okay—he liked it, aside from when the workmen started drilling in the distance. That sound reminded him of the explosion.

Eighteen months earlier, he had been on his way inside his uncle Teddy’s place. When he turned the handle to open the door, a bomb had exploded, throwing Nikola against the opposite wall. He had suffered injuries to his abdomen, chest, and hands, which, out of sheer reflex, he had used to cover his face. It had meant a week in intensive care followed by a month on the ward. His mom and Teddy had been there every day, but the girl he was dating at the time, Paulina, had dumped him. It was just as well—clearly she wasn’t worth his time.

Like always, George had set up his dusty old radio on the floor. They listened to Mix Megapol—Bebe Rexha’s cocky voice was singing the same line over and over again. It was like working to a particular rhythm.

George turned down the volume. “You know that next week, you’ll have done your sixteen hundred hours?”

“Really?”

“Yes, really. You’ve been doing really well, Nicko. I’ll help you finish your certification. Your apprenticeship’s over, the board’ll approve you straightaway. You’ll be a qualified electrician. What do you say about that?”

George Samuel chuckled—his eyes narrowed again, and Nikola couldn’t help it: he had to laugh, too. He had to laugh hysterically. George Samuel, blind from laughter—Nikola, almost an electrician. It made sense. He would have a real job. A real wage.

Who would have believed that eighteen months ago? While he was lying in intensive care after the explosion and Linda was beside herself with worry about him being on the wrong track. Who would have believed that life could be good? Who would have believed that it might actually be really good?

They were all proud of him. Teddy, who had found him his apartment, patted him on the shoulder every time they met: “Glad you’re not following in my footsteps, Nicko.” His grandpa still tried to make him go to church, but now he just smiled when Nikola refused. “You’re on the right track, moje malo zlato. Your grandmother would have cried tears of joy.” Even the boss of Spillersboda Young Offenders’ Institute had called to congratulate him on his change of lifestyle: as though Nikola had uncovered three identical symbols on the millionaire scratch card.

But it was his mom who was happiest of all.

“Do you know what I think’s so good?” she had said one day that spring, when he was still attending classes at the adult education college and had told her his grades. They had been walking along the canal, and Nikola had glanced over toward Södertälje Centrum. The birds were twittering like crazy, and there was dog shit on the path.

“That I broke away from my old life?” he tried.

“No, actually. The best thing is that change is possible. I was worried while you were in Spillersboda, you know, and even more once you got arrested and after the explosion. But now we have proof. That people can change.”

Linda had a salon tan and was wearing Ray-Bans that covered half of her face, but Nikola could hear it in her trembling voice all the same: she might have been shedding a tear or two behind her glasses.

“You know, Nicko, you don’t need to believe that you have to be someone anymore, that you have to strive for status and that kind of thing,” Linda had said, pausing for effect. “Because you’re already someone.”

They had stopped at a park bench. Nikola had turned to her. She was wearing a Houdini fleece and walking pants of some kind: they didn’t really go with her tan and glasses. Body: outdoorsy Swede. Head: MILF warning. Ahh, strike that last part—that wasn’t the kind of thing you thought about your own mother.

The ground beneath the bench had been covered in seed shells. Albuzur—sunflower seeds. Nikola was a big fan. It meant that someone had spent a while sitting there before them, thinking things through. He had sat down. “I’ve got my Swedish exam next Thursday, and I have to submit an essay.”

“Exciting. What’s the essay on?”

“The Count of Monte Cristo. Have you read it?”

“No.”

“It’s one of Grandpa’s favorites, you know.”

“I can imagine. He’s a big reader. It’ll be fine, I know it.” Nikola’s grandfather was a reading wizard: a man who had moved to Sweden from Belgrade sometime long ago and who had always taken Nikola seriously. He remembered his grandpa sitting on the edge of the bed, reading aloud from “the classics,” as he called them. The Jungle Book, The Three Musketeers, The Count of Monte Cristo.

At the same time, his grandpa had also raised Uncle Teddy—one of southern Stockholm’s legends in his day. Nikola couldn’t reconcile the two in his mind.

Chamon’s Audi A7 was parked in the middle of all the construction machinery outside the half-finished shopping center. Like always: his friend’s collection of parking fines was fatter than one of Escobar’s wads of cash. Not that Chamon cared—the car wasn’t registered in his name. They never were. Vorsprung durch Technik—or, as Chamon liked to say, “Forward through Babso.” That was the name of the guy who had four hundred cars registered to him in Södertälje.

It was Thursday, but Nikola wouldn’t be working tomorrow. In other words: it was the weekend. George Samuel had agreed to let Nikola go at two thirty. They would see one another again on Monday, like usual.

Chamon started the engine. “You heard that Audi’s releasing a new flagship model, the Q8?”

“Yeah, I read about it. It’s gonna have the V8 engine. But weren’t you talking about getting the new Lexus, the LS?”

Chamon stared at him. “Are you kidding me? I’m from Södertälje. I only drive German.”

Things were going well for Chamon—clearly—and his car was the strongest evidence of that. Then the watch, then the other jewelry, then where he went on vacation; people didn’t care where you lived. They never talked about where Chamon got his money from—even if Nikola knew that he dealt to chalk-white innercity kids at their insanely wild rave clubs. You didn’t talk about that kind of thing, even with your best friend—especially not if that person wasn’t part of The Life themselves. Nikola did sometimes long for it: for what he’d once had. The freedom. The lack of control.

They went back to his place, watched a few episodes of Narcos for the second time: loved it when Escobar inspected the coke factories in Medellín. They went down to buy kebabs. Chamon pulled out a couple of grams of weed, which they smoked in Nikola’s hookah—Nikola needed these chill moments. Ever since the explosion, something had happened to him, even if he couldn’t quite put his finger on what.

He and Chamon laughed. Listened to music. Leaned back on the sofa and just chatted.

After a few hours, Chamon looked up. “Nicko, do you believe in God?”

“Nah, not really.” This was classic Chamon crap talk. “I believe in fate. And my dachri.”

But Chamon didn’t laugh. “Do you believe in God or not?”

“Shit, man, I don’t know.”

Chamon drew on the pipe, then he kissed the thick gold cross that hung around his neck on an even fatter chain. “I do.”

“Why?”

His friend’s eyes were glossy. “ ’Cause there’s got to be something other than this.”

“Than what?”

“Bro, I don’t get any sleep at night. I wake up every fifteen minutes and peer round the curtains. If I hear a noise on the street behind me, I drop to the ground. The minute I see a car I don’t recognize, my stomach turns. I’m getting fucking ulcers.”

“But you’re free. You don’t have to get up at five every morning like I do.”

“I dunno, man, maybe you don’t have it so bad. It’s hard to explain, but sometimes I feel like I can’t do it anymore, like I’m tired of the whole thing, I don’t have any power. You know how many people’ve been killed these past few years? You know how many brothers have vanished? But the people making the decisions don’t give a shit. They’re all such whores, you know. I want to do something else sometime. Travel, you know? Or try out music or something. You know what I mean?”

“Music?” Nikola didn’t recognize his friend: want to do something else sometime—that sounded more like his mom’s nagging than Chamon.

“I mean, I’d like to learn an instrument. I was playing football for a while, but my mom always said I had an ear for music, that if I heard a tune once, I could sing it back perfectly later. She said I was musicalistic, or whatever it’s called. But dachri, these days all the undercover cops and snitches are fucking my head so much, I can’t hear a thing in there. Won’t be long before there’s none of me left. Not even sweet tunes.”

Nikola tried to work out how serious this conversation was. He thought about George Samuel and about how the most difficult thing he’d done today was to pull four insulated copper wires through a conduit.

And Nikola knew: he had made the right decision. Almost an electrician.

The Life wasn’t for him.

3

Emelie got up, smoothed the creases in her pants, and went out to greet Marcus. Anneli, the secretary she and the other lawyers shared, had already buzzed him in through the door downstairs. If Marcus had taken the stairs, he should be ringing the buzzer in approximately seven seconds. But if he had gone for the elevator, it would be a few more. It was a kind of litmus test, Marcus’s first. Emelie’s own inclination was always to take the stairs, regardless of how heavy the files in her briefcase were. Not that it really made much difference; she had already offered him a probationary position as a lawyer. There was no denying that it was a big step. Emelie had been running her own firm for just under eighteen months now, but the number of cases had exceeded expectations. She no longer had time to handle everything herself, which she knew was a luxury. Still, it was a risk—from today on, she wouldn’t just be responsible for paying her own salary. From now on, Emelie Jansson Legal Services AB would have to bring in enough money to cover two wages every month, one which came before her own. The curse of the small business owner, she thought. If Marcus was ever unwell or unable to handle the work, or if he simply didn’t manage to invoice properly, it was the firm that would suffer, and it might not survive. Her dream might come crashing down. But she needed someone to lighten her load all the same: in that sense, it was a must. She had too much to do. Marcus was tall and well built, with a thin, neat beard, and as they shook hands, Emelie noticed that he smelled good. He had probably taken the stairs. For a brief moment, she had thought he was expecting a hug, but she was his boss and employer now, even if there were only two years between them. Besides, she wasn’t the hugging type.

“Please, come in. I’m so glad you could start today.”

Marcus was wearing a navy suit, and his slacks were slightly too short, but that was just the fashion right now. The top button of his shirt was undone, and he wasn’t wearing a tie, which was fine, given that he wouldn’t be in court today. To begin with, he would just be getting to grips with everything. The way he moved reminded her of Teddy, she thought: calm and deliberate.

“Let’s go to my office,” said Emelie. “Would you like anything to drink?”

She had asked Anneli to make sure there was freshly brewed coffee in the machine, and a couple of bottles of Ramlösa water in the fridge.

“Please. You wouldn’t have any caffeine-free tea?” Marcus asked.

Caffeine-free tea, Emelie thought. That sounded quite unlawyer like, though maybe it was just something else that was trendy right now. She turned to Anneli and passed on the request.

“Nope, afraid we’re a bit low on the caffeine-free today,” the secretary said with a wry smile. The only thing Emelie and the other lawyers drank was coffee, coffee, and more coffee.

They went into her office. On one wall, she had a framed Mark Rothko painting. It was a poster, of course, a flat expanse of red that faded to brown and then something close to yellow. Emelie liked it; she thought it brought a sense of calm to the room, even if the fact it was only a poster reminded her of her previous employer, Leijon. Magnus Hassel, the partner she had worked with there, collected contemporary art, and he had both Warhol and Karin “Mamma” Andersson canvases hanging next to works by Giacometti and Bror Hjorth in his office. But that was history now. She had resigned from Leijon because they wouldn’t agree to her taking on a defense case. And then she had taken what had to be seen as a giant leap into the world of law: from being employed by one of Europe’s best corporate firms to renting an office and a quarter of a secretary’s time in a space she shared with three old human rights lawyers. Her former colleagues at Leijon had raised their eyebrows. A downgrade, a desperate fall from the elite to the D-list. She could, at least, have applied for a position with one of the renowned criminal firms, worked for the courts or with the Swedish Prosecution Agency, if what she wanted was to work on human-centric cases like that? It was just that it didn’t suit Emelie—she wanted to be left to her own devices, that felt important, she’d had enough of bosses getting involved. And she knew she could be one of the best.

Marcus placed his bag on the floor. It was made from dark green canvas and looked pretty expensive. She didn’t know much about his background; all she knew was that he had gone to high school in Kärrtorp, in the suburbs, and now lived centrally, in trendy Södermalm. The salary she had offered him was one thousand kronor less than he had been getting from the small-family law firm where he had been working before—and the fact that he had agreed to it was proof of his commitment. If he was as good as she hoped he was, he would soon be on commission.

“So,” she said, pushing a laptop over to him. “This is your computer. You’ll need to choose a password and that kind of thing. You’ll be in the room next door. I’ve ordered you a desk and a chair, but they’re not being delivered until next week. Sorry about that, but until then you can work in here. Hope that’s okay.”

“Absolutely, but would it be okay if we turned off the light?”

Emelie looked up. She didn’t understand.

“It’s just, I’m allergic to electricity. I can’t handle it. I prefer to work by candlelight or with a paraffin lamp, and I like to use a pen and paper rather than a computer.”

Emelie stared at the young lawyer in front of her. She had made up her mind about Marcus Engvall immediately after her interview with him: he had top grades from his placements and kind words from his previous employers, and he was passionate about people-centric law. He also seemed to have a sense of humor, a good temper, and courage—the former were important for the clients, and the latter essential for this type of work. Courage: not many people talked about it, but it was the most important quality in a defense lawyer. But now: her suspicions should have been raised at caffeine-free tea. What was this? Allergic to electricity? That wasn’t even a thing.

Marcus smiled, winked. “Don’t worry, I’m just kidding. I’m happy to work in here. With the lights on.”

He placed his phone on the desk. The screen was cracked.

“And I don’t have anything against electrical devices. In fact, I’m a bit of a tech nerd.”

Emelie laughed. Marcus did, too. So he did have a sense of humor.

It was actually Magnus Hassel who had given her Marcus’s name a few months earlier. Emelie had been waiting for Josephine, who still worked at Leijon, at a restaurant called Pocket City when she heard someone say her name. She had turned around and realized that two of her old bosses were sitting at the next table. Magnus Hassel and Anders Henriksson. How could she have missed them? Back when she was at Leijon, they were the ones responsible for her yearly development meetings, something she didn’t exactly miss. She remembered them well.

Anders Henriksson was somewhere north of fifty, but he probably dyed his hair and Botoxed his forehead to make himself look closer to thirty. A few years earlier, he had married a secretary twenty-five years his junior, and yet the transformation wasn’t quite complete: he still thought Zara Larsson was a Spanish clothing brand and saw Harvey Weinstein as a hero. But that wasn’t his claim to fame, nor was his so-called EQ—in that respect, it was probably fair to talk about him being exceptionally challenged. Where Anders Henriksson really shone was in his performance. He was behind several of Sweden’s most respected M&A deals, known for not winding down despite approaching retirement age, and listed in all the most important rankings as “A brilliant analyst—creative and authoritative.”

Magnus Hassel, on the other hand, had never needed any further introduction. He was Mr. M&A in Sweden; anyone who was anyone in the Swedish business world knew who he was, and not just the lawyers. He had held the hand of the biggest business leaders, MDs, and industry giants, and led them to even greater riches. According to Dagens Industri, Magnus Hassel had brought in twenty-five million kronor in bonuses in the last year alone.

But all that belonged to her old life. Emelie had entered a new arena now. Far removed from the flashy offices, billionaire clients, and exotic jurisdictions. And with half the income.

It was Magnus who had forced her to resign, who had turned up while she was defending Benjamin Emanuelsson in court and spent an entire day listening to her in the public gallery. She should hate him. And yet she knew he had a high opinion of her and that he really had tried to make her change her mind, to stay at Leijon. Emelie couldn’t dislike him 100 percent. Only 98.

“I didn’t think you came to these parts anymore,” Magnus had said. He was casually dressed: a green tweed jacket, jeans, and a pink shirt. Jeans—during her three years at Leijon, Emelie couldn’t remember ever having seen him in anything so casual. “I thought people like you stuck to Kungsholmen and the satellites.”

Technically, he was right. The majority of Stockholm’s criminal law firms were based in Kungsholmen. Its proximity to the Stockholm district court, police HQ, and the main custodial prison made it the natural neighborhood for anyone who liked to be able to walk to their meetings, interviews, and hearings. She spent much of the rest of her time at the district courts in Södertorn and Attunda, or the smaller custodial prisons in Huddinge and Sollentuna.

“The satellites,” as Magnus called the inner suburbs, made Emelie think of the Eastern Europe of the past. Satellite countries, Soviet vassals.

“I’m meeting Jossan,” Emelie had said. “And she doesn’t like straying far from sanctuary.”

Magnus had laughed. Anders Henriksson, on the other hand, hadn’t reacted. Emelie had thought back to his scarlet face when he and Magnus first confronted her about taking on the Emanuelsson defense.

“I’ve heard things are going well for you,” Magnus had said, raising his glass as though to toast her.

“Yeah, I actually have a bit too much to do. I should probably hire an assistant.”

“You should be happy, then. But you still can’t be earning as much as you were with us?”

Emelie had wondered whether his mocking was friendly or whether he was genuinely trying to provoke her. She had raised her still-empty glass to him. “You pay a price for being at the top.”

Anders Henriksson’s face had changed color at her last remarks. But Magnus just laughed.

“Listen,” he had said, leaning forward. “I actually think I know a kid who would be a great fit for you. He applied for a job with us last week, he’s a newly qualified lawyer, he’s been in court, seems smart, hardworking, like you.”

“Why didn’t you hire him, then? I thought you liked workaholics?”

Magnus had leaned even closer, his mouth practically brushing her ear. “He talked about working for the rights of the individual and defending a system that should provide support to everyone. He actually sounded worryingly like you. He’s a vegan, too, and there’s no trusting people who don’t want to eat dead things.”

Emelie leaned back and studied Magnus. His eyes glittered. “Tell him to send me an application,” she said.