6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

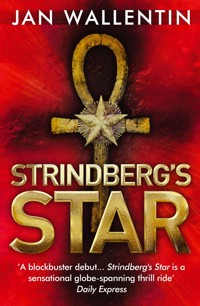

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

THE INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER China, 1895 In the shifting sands of the Taklimakan Desert, a new Pompeii has come to light and, with it, two remarkable artefacts - a metal ankh and star, covered in strange inscriptions. The Arctic, 1897 A hydrogen balloon is readied for a polar voyage. Publicly, it is a patriotic attempt to put Sweden in the lead of the race to the North Pole. Privately, the three men on board are committed to another, much more dangerous mission... Sweden, 2011 260 meters under the earth, in a long-flooded mineshaft, a diver's torchbeam plays over a corpse with a fist-sized hole in its forehead. Skeletal fingers clutch a metal amulet. It is the key to the annals of a secret history so deeply buried that the few who knew of it thought it lost forever. Until now...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

First published in Sweden in 2010 by Albert Bonniers Forlag.

First Published in the United States in 2012 by the Viking Press, a division of the Penguin Group.

First published in Great Britain in hardback and airport and export trade paperback in 2012 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jan Wallentin, 2012

The moral right of Jan Wallentin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Rachel Willson-Broyles to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 84887 987 4 Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 988 1 E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 680 3

Printed in

Corvus An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Excerpt from my diary in the year 1896.

May 13th.—A letter from my wife. She has learned from the papers that a Mr. S. is about to journey to the North Pole in an air-balloon. She feels in despair about it, confesses to me her unalterable love, and adjures me to give up this idea, which is tantamount to suicide. I enlighten her regarding her mistake. It is a cousin of mine who is risking his life in order to make a great scientific discovery.

—Inferno, August Strindberg

That which has been is far off, and deep, very deep; who can find it out?

—Ecclesiastes 7:24

Contents

The Invitation

1

1 Niflheim

2 Dalakuriren

3 The Æsir Murder

4 Bubbe

5 Copper Vitriol

6 Up into the Light

7 A Secret

8 Northbound E4

9 La Rivista Italiana dei Misteri e dell’Occulto

10 Don Titelman

11 Solrød Strand

12 The Interrogation

13 The Dream

14 Eberlein

15 Elena

16 Strindberg

17 The Awakening

18 The Eagle

19 The Postcard

20 The Syringe

21 The Ankh

22 The Station

23 The Car

2

24 Ypres

25 Saint Martin d’Ypres

26 Stadsarchief

27 In Flanders Fields

28 Saint Charles de Potyze

29 The Glass Capsules

30 Les Suprêmes Adieux

31 The Telephone

32 The Tower

33 The Visit

34 The Login

35 Mittelpunkt der Welt

36 Wewelsburg

37 The Blindness

38 The North Tower

39 Brüderkrankenhaus St. Josef

40 Mechelen–Berlin

41 Healed

42 Changing Tracks

3

43 Мурманск

44 Yamal

45 The Seventy-seventh Parallel

46 The Third Day

47 Agusto Lytton

48 Eva Strand

49 Jansen

50 Under the Surface

51 Changing Course

52 The Opening

53 The Black Sun

54 The North Star

55 Gone with the Wind

The Letter

The Invitation

His face had really withered. The makeup artist’s tinkering couldn’t hide that fact. Yet she had still made an effort: fifteen minutes with sponge, brush, and peach-colored mineral powder. Now, as she replaced his aviator glasses, there was a sickly shine over his grayish cheeks. She gave him a light pat on the shoulder.

“There, Don. They’ll come and get you soon.”

Then the makeup artist smiled at him in the mirror and tried to look satisfied. But he knew what she was thinking. A farshlept krenk, an illness that was impossible to stop—such was growing old.

He had rested his shoulder bag against the foot of the swivel chair. When the makeup artist left, Don bent down and started to rummage through its contents of bottles, syringes, and blister packs. Popped out two round tablets, twenty milligrams of diazepam. He straightened up again, placed them on his tongue, and swallowed.

In the fluorescent light of the mirror, the hand of the wall clock moved a bit. Thirty-four minutes past six, and the morning news murmured from the closed-circuit TV. Eleven minutes left until the first studio guests were on the couch.

Then he heard a knock, and a shadow appeared in the doorway. “Is this where you go for makeup?”

Don nodded at the tall figure.

“I’m off to channel four later,” said the man, “so the girls might as well apply enough to last.”

He took a few steps across the yellow-speckled linoleum floor and sat down next to Don.

“We’re gonna be on at the same time, right?”

“Yes, it seems like it,” said Don.

The swivel chair creaked as the man leaned closer.

“I read about you in the papers. You’re the expert, aren’t you?”

“Not really my area of specialization,” said Don. “But . . . I’ll do my best.”

He got up and removed his jacket from the back of the chair.

“In the papers it said you know this stuff,” said the man.

“Well, then it’s got to be true, right?”

Don put on the corduroy jacket, but as he put the strap of his bag over his shoulder, the man grabbed it. “You don’t have to act so fucking important. I’m the one that found everything down there, aren’t I? And by the way, there’s . . .”

The man hesitated.

“By the way, there’s something I think you could help me with.”

“Oh?”

“There’s . . .”

He cast a quick glance at the door, but there was no one there.

“There’s something else I found down there. A secret, you could say.”

“A secret?”

The man pulled Don a little closer, with the help of the shoulder strap.

“It’s at my place in Falun, and if it’s possible I’d really like for you to come up to my house and . . .”

His voice died away. Don followed the man’s eyes to the doorway, where the presenter was standing and waiting in a light brown suit jacket and a frumpy skirt.

“So . . . I see you’ve gotten to know each other?”

A stressed smile.

“Perhaps you two can talk more afterward?”

She pointed out toward the hallway, where a cue light was glowing in red: ON THE AIR.

“This way, Don Titelman.”

1

1

Niflheim

With each step, Erik Hall’s rubber boots sank deeper into the mud, and his legs were tired. But it couldn’t be much farther now.

When, through the fog, he could make out the clearing past the last trunks, he came to a halt, and for a moment he felt uncertain. Then he caught sight of the ruins of the old fence. The rotting stumps stuck up like warning fingers in front of the slope down to the opening of the mine shaft. He slid down the incline to the ledge in front of the mouth of the shaft, pulled off his three dive bags, and stretched his back.

It was cold here, just like yesterday, when he had managed to find his way to the abandoned mine for the first time. The heavy pack of tanks with the inflatable buoyancy vest was still lying where he’d left it, and the same horrible, rotten stench was still in the air.

The fog had reduced the light to dusk, and it was hard to make out any details as he leaned over the steep shaft. But when his eyes had adjusted, he could make out the supports that started at a depth of about thirty yards. They braced the walls of the shaft, and an image of sparse, blackening teeth flashed by. Like looking down into the mouth of a very old person.

Erik took a few steps backward and carefully inhaled. The smell seemed to subside as he got farther from the hole.

He gave himself a pat on the back. He’d been able to make his way in this darkness and find the right route yet again; there weren’t very many people who could pull it off.

Anyone could use a GPS navigator to get from Falun to an address out by Sundborn or Sågmyra. But finding the right place three miles straight out in the wilderness—that was different.

Most—in fact, all—abandoned mine shafts were supposed to be noted on the maps. The surveyors from the Mining Inspectorate had seen to that. But this hole had apparently been overlooked.

Erik heard a faint buzzing, as some flies had started to gather around him. They made their way in curiosity down into his bag to see if there was any food.

But in the first bag there were only spools of rope, snap hooks, and bolts. The double-edged titanium knife with a concave and a sawtooth edge. A battery-powered rotary hammer drill, the climbing harness, and the primary dive light that he would fasten to his right dive glove.

When Erik had dumped everything out on the yellowed grass, he opened the side pocket of the bag. In it were the Finnish precision instruments in hard cases. He unpacked a depth gauge, which would measure how far down he sank under the surface of the flooded shaft, and a clinometer to estimate the gradients of the mine paths once he got there. The flies had increased in number; they hovered around him like a cloud of dirt.

Erik waved the insects away from his mouth, irritated, while taking the regulators and long hoses that would keep him alive out of the next bag and checking the pressure of the tanks. Then he moved backward a few steps, but the cloud of flies followed him.

Half standing in the gravel, he pulled off his green rubber boots, then his camouflage pants and his Windbreaker. With bugs crawling across his face and neck, he opened the cover of the last bag. Under dive computers and a headlamp waited the bulky wetsuit and the rubberlike skin of the dry suit. Glossy black three-layered laminate fabric, specially developed for diving in forty-degree-Fahrenheit water.

He pulled on the full-cover neoprene hood. Now the flies could reach only his eyes and the upper part of his cheeks. Then he took out the bag that contained his fins and mask. At the opening of the shaft, the rotten-egg stench almost made him change his mind, but then he attached a nylon rope and began to lower the bag.

Forty, fifty yards—he managed to follow its jerky descent that long—but the line just kept going. Only after a few minutes did it reach the water that filled the lowest part of the shaft.

He secured it with a few loops around a block of stone, and then he went to get the bundle of climbing gear and hooks. When he got back to the shaft, he sank down to his knees.

A strident roar from the hammer drill finally broke the silence, and he could soon attach the first bolt. He pulled—it would hold. He drilled bolt number two.

Then he lifted the hundred-pound pack with tanks, the buoyancy compensator, and the hoses onto his back and fastened the strap of the climbing harness across his chest and did a few tests of the self-locking rappelling brake that would control the speed of his fall down into the shaft. He swung himself over the edge, the brake hissing as he dropped.

There were blurry pictures on the Internet from urban explorers in Los Angeles who, without a map, hiked their way through mile after mile of claustrophobic sewer systems. You could find texts from Italians who dedicated themselves to crawling through rats and garbage in ancient catacombs, and from Russians who described expeditions to ruins of forgotten prisons from the Soviet era, hundreds of feet below the ground. From Sweden there were video clips that showed dilapidated mine shafts where divers swam in pitch-black water. They crawled through tunnels that didn’t seem to end.

Some called themselves the Baggbo Divers and hung out outside of Borlänge. Then there was Gruf in Gävle, Wärmland Underground in Karlstad, and several groups in Bergslagen and Umeå. And besides them, there were people like Erik Hall, who went diving on his own and most of all wanted to keep to himself. It wasn’t recommended, but people still did it.

Because they shared tips about equipment and shafts that were worth exploring, all of the mine divers in the country knew of each other. Year in and year out, it was the same people who did it. Without exception, they were men.

But a month or so ago, a group of girls had started putting up pictures of their mine dives on the Internet. They called themselves Dyke Divers. No one knew where they came from or who they really were, and for their part they didn’t answer any questions. At least not the questions that Erik had sent as a test.

At first when he was surfing around the girls’ Web site, he had found only a few grainy photos. Then clips of advanced diving had shown up, and yesterday there had suddenly been a snapshot from a mine shaft in Dalarna.

The picture had shown two women in diving suits down in a cramped mine tunnel: pale cheeks, bloodred mouths, and both had shining black hair trailing over their shoulders. Behind them they had spray painted:

545 feet, September 2

Under the photograph, the girls had listed a pair of GPS coordinates, which marked a place near the Great Copper Mountain in Falun. The position had been only ten or fifteen miles from Erik Hall’s summer cottage. They added:

Flooded shaft from the 1700s we found on this:

/coppermountain1786.jpg/map, blessings to the county archive in Falun. After the scrap iron in the water, there are tunnels for whoever dares to pass.

No country for old men ; )

The self-locking rappelling brakes lowered him gently into the depths. The cloud of flies was still circling up by the opening, but down here in the dark, Erik was hanging alone. He breathed only through his mouth now to avoid the smell of sulfur.

When he let his eyes drift around, it was like sinking down into a different century. Rusted-away attachments for ladders, half-collapsed blind shafts, notches cut by pickaxes and iron-bar levers.

There was no room for mistakes when lowering yourself down into a mine. But he tried to persuade himself that this shouldn’t be difficult, just a vertical hole and dirty support posts that had managed to withstand the strain of the rock for hundreds of years.

Still—older mine shafts were never truly safe. What looked like a wafer-thin crack could run deep into a rupture. And if the wall gave way, it would mean that one of the one-ton boulders hanging above him could suddenly come loose and tumble down.

How much farther?

Erik broke a glow stick and let it fall. The glowing flare disappeared in the dark, but then he heard a splash much earlier than he had dared to hope for. The stick glittered green far below, bobbing on the black water.

The depth meter on his wrist indicated that he had already lowered himself some 225 feet, and the cold had only gotten worse. Frost glistened on the rock wall in front of him, and the next glow stick landed on an ice floe.

Then he discovered that a small ledge stuck out just above the water. It was about ten yards to the right, so he swung himself along the rough boulder and landed.

Now to the most important part.

He took out a little bottle of red spray paint from the leg pocket of his suit and with a few quick movements, he sprayed a large E and an H. Under the letters, Erik Hall wrote: SEPTEMBER 7, DEPTH OF 300 FEET, then snapped a few pictures.

He pulled off his neoprene hood and ran a hand through his curls. Several more flashes. He examined the results on the camera’s display.

His hair was a bit thin, now that he was over thirty, but it was hardly something you’d notice. The dark circles under his eyes made more of a dramatic impression than anything else, Erik thought to himself.

Then he sank back down into a crouch in the stench and the cold. He tried to forget that no one knew where he was and that no one would miss him if he drowned or disappeared in the tunnels far below ground.

The Dyke Divers had left bolts where he could secure his navigation line before his dive. When it was fastened, he pulled on his flippers and mask and put the regulator in his mouth for a first test breath. Before he had time to exhale, he had already taken a large step down into the water. The roll of line he was holding in one dive glove spun quickly, and above him he could see how the strong wire cut through several layers of ice as it followed his sinking body.

Below the surface, the better part of the light from his headlamp was swallowed by the dark walls. But the water was relatively clear, and the beam carried farther than he had dared to hope.

Erik braced himself against the wall of the shaft and pushed out into the emptiness. The safety line followed him, winding through the water like a tail.

The bottom appeared in the light from the lamp on his right wrist. Under him were remains of the litters that had been used to carry the ore out of the tunnels. Erik moved his fins carefully and floated weightless above a wheelbarrow. His underwater camera began to flash and take pictures of the iron gear that had long ago been forgotten and left behind. Precision tools, sledgehammers, chisels, an ax, cracked pump rods, and farther off . . . something that looked like a track.

Erik let his body sink, and he landed next to the narrow-gauge rails. The depth gauge read sixty-nine feet under the surface of the water. Even with a slow ascent to avoid the bends, he still had plenty of air left.

He sailed above the rails, which led him away from the middle of the shaft. He had the sensation that he was moving into a narrower space and slowed his speed. That was when he caught sight of the timber-framed opening of a tunnel, where a yellow scrap of fabric was speared onto a hook.

Erik glided forward a few more yards, and he illuminated the scrap with the light from his headlamp.

It wasn’t fabric hanging there by the entrance to the tunnel, it was a strip of bright yellow seven-millimeter neoprene. Triple seams, made to be highly visible in cloudy water. The girls must have cut up an old wetsuit in order to mark the right way in.

The tunnel was perhaps two yards high, and a rusting mine car stood in the middle of it. Above the car there was a small space where it looked like he could pass.

Perhaps this was the beginning of a long system of tunnels and shafts—without a diagram or a map, it was impossible to know. But according to the Dyke Divers’ pictures, it would lead to someplace that was dry.

He managed to make his way over the rusted-down mine car and tried to increase his speed gradually. With a third of his air in reserve, a total of forty-five minutes of dive time remained. Fifteen minutes tops in this direction, before he had to turn around and make his way back to the surface.

The farther he got into the tunnel, the more it began to slope upward. His clinometer showed a gradient of eleven degrees upward, and it was only getting steeper.

Only about a hundred yards more. Then the tunnel would presumably be at a higher level than the flood, and it would stretch out, dry and full of air. Or . . . the tunnels, because now he had come to a fork. The one that continued to the left seemed navigable. The right-hand one was barely a yard wide, dilapidated and tight.

He couldn’t see very far into the dark passage with his headlamp. But the light was more than sufficient to show the yellow strip of neoprene, which indicated that the Dyke Divers had taken the difficult path. Slender female bodies, and there had been several of them, could help each other. He was alone, as always, and wouldn’t even have enough room to turn around, if he should be in a hurry to get out.

Erik let his glove stroke along the frosty ore and hung there, weightless. Then he chose to continue to the left, but quickly felt like giving up, because only a bit farther he noticed that this tunnel also quickly began to narrow.

Ten yards, twenty, thirty. Soon he would be able to brush both walls with his fingertips. At forty yards his shoulders grazed stone. Forty-five. Two iron supports made a narrow doorway. He twisted his body to the side and managed to force his way through.

But the tunnel became increasingly narrow, and before long he reached two more supports, this time so close to each other that he would have to tear one out if he wanted to keep going.

Erik directed his flashlight to where the support was attached to the ceiling and the floor. It wouldn’t be possible to dislodge. The right support’s floor attachment seemed to have rusted away. Two bolts had detached at the ceiling . . . and two still seemed to hold. He grasped the right support and moved it carefully. It moved an insignificant amount. If he were to really put his weight into it . . .

Erik hung suspended above the narrow-gauge rails.

Then he let his headlamp search the darkness as far into the tunnel as possible. To turn around now . . . he shoved on the support again, and it unexpectedly came away from the wall in a cascade of gravel and small rocks. His view became clouded, and he curled up to protect himself, expecting the immediate collapse of the rock. After a while he began to search through the silt with his gloves. With lumbering movements, he managed to squeeze his way through.

After the bottleneck, the tunnel widened again. He had to hurry now. Maybe the Dyke Divers’ tunnel and this one would converge again, just a bit ahead? Surely he had gone another ninety or hundred yards in just a few minutes. Hundred twenty, hundred thirty. It shouldn’t be long before he reached the surface, because the upward slope was still just as pronounced.

He was so busy keeping an eye on the narrowing walls that he didn’t realized until it was almost too late that he was about to swim into an iron door. It was completely rusty, with gaping holes, and it hung from the tunnel wall on crooked hinges. Through one of the openings he could see the bolt that kept the door from opening.

Erik let his light play over the brittle brown metal . . . and what was that? A lime deposit?

He swam a little closer.

No . . . not lime. White lines of chalk. Someone had written large, shaky letters, an incomprehensible word:

NIFLHEIM

Niflheim . . . maybe it was the name of the mine itself?

Erik placed the fingers of his diving glove against the rusty surface and gave it a careful nudge.

The door moved, if only a bit.

He pushed harder, and through the water he could hear the hinges creak.

Erik took a deep breath from the regulator. Then he pressed both of his diving gloves against the door and pushed with all his might.

Creaking, it swayed suddenly as the hinges came loose from their attachments. As it fell it swirled up a cloud of mud, and the water turned brown.

He pushed himself forward, but didn’t see the stairs that rose behind the iron door and when his forehead hit the bottom steps, the diving mask was wrenched off and the regulator torn out of his mouth. The sudden cold gave him such a shock that he immediately swallowed water in a choking gulp. He started to fumble blindly for his backup hose, but couldn’t find it. With his eyes shut tight, Erik flailed about and his lungs burned for air.

Air—

He desperately raised his head up and was suddenly above the surface of the water again. Snorting, spitting, and when he instinctively inhaled through his mouth and nose: that nauseating stench.

He hyperventilated so that he wouldn’t fall forward and immediately throw up, and then crawled up the last few steps of the stairs and collapsed; just breathe through your mouth, just through your mouth now . . .

When his breathing calmed, he rolled over on his back and rested, until he slowly managed to sit up.

Erik noticed that he had dropped the lifeline that indicated the path back to the original shaft. He had no energy to return. The water must clear up first.

The smell of rotting made it hard to think.

He pulled off his fins and the mask, which had ended up hanging around his neck. The continuation of the mine tunnel ran away into a nightlike darkness, narrow and damp. He stood up on his reinforced-rubber dive shoes and started to walk.

The ore was even and regular where the tunnel had been burned out of the rock. The tunnel branched off suddenly, and he went to the right. Then there was another branch, but here the right side was filled with rocks. Left this time, then, and then right again when it branched into three. But it was a dead end, so back out to the fork. Which tunnel had he actually come from? At a loss, he stood in the smell of decay and death.

He moved, bent forward, farther and farther into the labyrinth. There were no longer any signs of mining in the tunnel, only clusters of stalactites that hung down from the tunnel’s low ceiling. It was cold, a bitter cold that penetrated even the three-layer laminate of the dry suit.

What if he never made it up again? How long would it take before someone wondered where he was? Would anyone start looking for him? Erik Hall hit the tunnel wall with his glove and the beam of light wavered.

Mom had been gone for a long time, and for some reason it struck him to think about what he would leave behind in the lonely cottage. The extent of his fame: three old newspaper clippings.

One of the blurbs, a few inches long, said that he had scored eleven points for his school basketball team in a game long ago. The second was a picture from when the local paper had visited Dala Electric, although he was a little bit hidden from sight in that one. Then there was the achievement itself: a short quote from the big evening paper, when they had done a summer report on the mine in Falun. In that one he’d actually gotten his whole face in. He suddenly remembered: Dyke Divers; he couldn’t forget why he was here.

Erik stopped.

This really must be the end. He looked at his depth gauge, which showed an inconceivable depth of 696 feet. Over 150 feet farther down than the girls, and he had done it without help from anyone.

He took out the spray can with stiff, frozen fingers and shakily sprayed another set of initials: E-H, 212 METERS. Then he thought for a second and added: AD EXTREMUM—at the limit.

He took a few pictures with his underwater camera and then let the light of his headlamp sweep over the tunnel walls. There was something there—

He took a step closer.

Another door? He really ought to turn back.

Yes, it was another iron door, the same kind, the same bolt, this one on the inside, too. The same . . . chalk?

NÁSTRÖNDU

The thick air streamed into his lungs. Náströndu?

He gave the door a light push.

It immediately gave way, swinging wide open on screeching hinges.

When Erik got control of his breathing again, he finally dared to move forward and peek in.

A stairway wound steeply downward, just behind the door.

Ten extra minutes.

He set the timer on his dive watch and his rubber shoes squeaked as he took a first step.

The stairway formed a tight spiral, as coil after coil led him deeper and deeper. At the opening at the end was a large cave, surely sixty feet high.

There was a slow drip of water that fell down into an overflowing pool. In the middle of this pool rose a stone, and on top of the stone was something that resembled a sack.

The air was heavy to breathe; it flowed like mud and the smell was worse than ever.

Just a quick lap around, and some pictures.

He tried to move as silently as possible, but the scraping of the gravel echoed through the cave. He stopped to calm himself down and listened to the drops that were falling.

The light from his forehead swept over the walls. A vein of copper glimmered to the right, all the way up to the ceiling of the cave.

Erik gave a start when he saw something that resembled an arch-shaped opening to the left. But when he came closer and let his glove glide over the hard surface of the rock, he realized that he had only been tricked by the play of shadows. He shone the light to the left once more and then . . . but there was something there! The same shaky lines of chalk—but this time whoever had written them had striven for more than isolated words.

Erik could barely decipher the writing. He took out his camera. It flashed, and he looked disbelievingly at its screen.

On his way back to the stairs, it occurred to him that perhaps he could take a souvenir with him. Something from that sack, maybe, the one sitting over there on the rock in the pool . . . ? He waded out into the waist-high water. When he finally reached the sack he saw that it was covered with something that looked like a moldy net.

Erik took off his gloves in order to get hold of it.

The net was a wet, slippery tangle of gray and black strings. He tried to lift them away and caught sight of an entangled object. He grasped its shaft of shining white metal.

But he couldn’t get the shaft loose; it seemed to be attached. He felt farther up along the sleek surface and encountered three tied ropes.

Erik took out the titanium knife and cut through the first rope fastening. It snapped. Snapped? Was the rope so old that it had become petrified?

He took hold of the second tie and made another cut. Another sharp snap, and now the whole sack started to move. Despite the cold, Erik felt a wave of feverish warmth. He cut off the third tie and let out his breath.

When the shaft came loose, he thought at first that it looked like an unusually long key. But when the light from his headlamp ran along the object, he realized that it was actually some sort of cross. It had a shaft and a crossbar, but above the crossbar there was an eye. It shone white in the darkness and had the oval shape of a noose.

With his bare hand, Erik grasped the mess of strings and tried to pull them aside to get to the contents of the sack. The strings seemed to be sewn on, so he got a solid grasp and pulled.

It was too late by the time he realized he had used too much force. With his tug, the whole sack came up into his arms, and he fell over under its weight. His head disappeared under the icy water of the pool. When he finally managed to sit up again, a twisted face stared at him in the light from his headlamp.

Paper-thin skin was drawn tight around the dead eyes of a woman, and above the bridge of her nose, in her forehead, gaped a hole as large as a coin.

Then he felt the three cut-off stumps under the water. Those weren’t ties he had cut off, they were the fingers of the woman’s hand. He instinctively tried to move backward, but her head followed him as though she were a rag doll. He pulled back again and realized that the strings he was holding were the corpse’s hair.

And when he breathed in through his nose, the odor of the body was apparent through the stench. The woman smelled like blood and iron and the summer warmth of barn walls. A smell that Erik could place at once. She smelled like Falu red paint.

2

Dalakuriren

Dalakuriren was a newspaper with hearty feature columnists and caustic political columnists, but when it came to news, it definitely did not have the leading editorial team in the country. Still, the news director had some degree of lingering aptitude: He could answer the telephone.

The tip had come in at three thirty on Sunday afternoon, just when writing fluff articles from the towns of Gagnef and Hedemora felt most hopeless.

The crackling cell phone line had made it difficult to understand details, but the main message from the freelance photographer calling in the tip had been simple: This was the story of a lifetime. In broad terms, the story was about—at least as the news director understood it—some girl (a teenager?) who had been found dead (a sex murder?) in a mine shaft (a spectacular sex murder?).

The person who had found the body and called the police—apparently some sort of diver, according to the freelance photographer—had managed to rattle off a whole series of numbers before the connection was broken, numbers that the operators had finally been able to interpret as GPS coordinates. And now the better part of Dalarna’s rescue teams were set in motion, out toward the location in the forest: three police patrols, a command car, two ambulances, plus the fire department, and with any luck, also some officials from the Mining Inspectorate, who knew all that stuff about mines.

After a frustrated lap through the Sunday-empty editorial office to find a reporter who could go, the news director found Dalakuriren’s extra resource—a lanky intern from Stockholm.

Two minutes of conversation later, the intern had tumbled away down the stairs with the yellowed newsbills, out to the staff cars in the courtyard.

The news director said a silent prayer and then set a course back to his desk. Which other papers had received the tip? He half ran past the rows of pale gray editing screens where tomorrow’s paper had already begun to take shape. Which pages would need to be redone? The front page, of course—but after that: Was this just a Falun thing, or would it turn out to be something really big that made it onto the national pages?

He began to write the short text for the Web edition of Dalakuriren. This would be snatched up right away by TT, the Swedish news agency, he knew it. The red TT flash would then set all the other papers in motion, and at first, people everywhere would cite Dalakuriren’s report:

BREAKING NEWS OUTSIDE FALUN: MURDER VICTIM FOUND 700 FEET UNDERGROUND

With the phone clamped between his shoulder and cheek, the intern skidded onto the forest road just south of Falun. The gravel from the freelance photographer’s car sprayed up in front of him. It was hard to drive and listen at the same time, but soon the intern understood the photographer’s directions; their destination was apparently some sort of rest stop.

Finally a straight stretch opened out, and when he saw the flashing lights far ahead, he realized that he had found the right place.

Several picnic tables had been turned over into the ditch and lay there with their built-in benches, looking like upside-down beetles. The police must have cleared them away to make room for all the rescue vehicles. The rows of vehicles had been forced to park so tightly that the hoods of the ambulances almost blocked the forest road. A bit farther on, the fire department’s ladder trucks stood tilting down into the shoulder, and only after the intern had turned past them did he find a place to park.

The intern yelled and waved to the freelance photographer to get out of his car, and with squelching shoes they entered the gloom of the spruce forest. Soon they could hear the police German shepherds just ahead of them, and all they had to do was follow the barking through the thick fog.

The mine shaft was already cordoned off; thin fluttering plastic tape blocked off the better part of the clearing around it. At the edge of the shaft stood half a dozen policemen and a few firemen, engaged in what seemed to be a muddled discussion about what should be done next.

Behind them sat a lone figure on a boulder. The floodlights that the rescue crew had aimed at the shaft made the black dry suit shine. His diving hood was off; his rough, craggy face was red; his eyes were swollen when he looked in the intern’s direction.

The freelance photographer nudged the intern in the side, and the intern gathered his courage, bent down, and slid under the plastic tape.

“You’re the one who found her, huh?”

At first it didn’t seem as though the diver understood the question. He just sat quietly for a moment and looked down at his big hands, but then he nodded stiffly.

“What happened down there?” the intern whispered, as he sneaked a look over at a nearby policeman.

“Something . . . something completely hellish, I think,” the diver answered.

The intern imagined a pale, naked body, a girl sprawled in claustrophobic darkness. He couldn’t help breathing a little faster. “So . . . how old was she?”

“How old? Well, I don’t know.”

The diver squinted uncertainly as their eyes met.

“The body was like a little girl’s. Completely soft, just as if she were still alive. And she didn’t actually weigh much. It was just that I slipped as I was lifting her, so she ended up on top of me. She had something in . . .”

“What did she look like, did she have any injuries?”

“Long hair . . .”

The diver waved, an attempt to explain with his hand.

“It was like a tangle in front of her face. I grabbed it, because I thought it was a bunch of loose strings.”

“But did she have any injuries?”

“Yes, yes! There was like a hole above her eyes . . . it was . . .”

A flash from the camera; the freelance photographer had crouched down a few yards away. For the first time, the diver looked at the intern with definite interest, and a twitch appeared in the corner of his mouth.

“Hey . . . is this going in the paper?”

At the editorial office, the news director started to type the intern’s quote.

BREAKING NEWS:GIRL RAPED, MURDERED IN MINE SHAFT THE DIVER’S OWN WORDS

“You can add ‘only in Dalakuriren,’ ” said the intern, because now he could see that the police were guiding the large diver into the forest. The ambulance personnel followed after them with their stretchers empty.

Then came a period of contented waiting. Dalakuriren hadn’t only been first, it had also gotten furthest with the story.

The intern and the freelance photographer had set up camp next to the trunk of a pine, where they tried to huddle together to protect themselves from the evening chill. And now a number of other teams began to gather in the dark. Swedish Radio and TT were there; the evening papers, of course; and next to the floodlights, TV4 and state channel affiliates had set up their cameras and tripods. Now and then the reporters went up to the rescue commander next to the stinking hole in order to update their reports, but the information kept changing.

First it was one of the local sport diving clubs that was going to help remove the murdered person from the shaft. Then the matter was passed along to the recovery divers from the coast guard in Härnösand. But at seven thirty, some high-up official in Stockholm must have happened to turn on the TV, because suddenly a special group from the National Task Force was supposed to solve the problem. Even though the Stockholmers had ordered a helicopter, it was easily three hours before they were on the scene. At that point, it was already a little past eleven o’clock.

Up till then, all the media outlets had had to cite Dalakuriren and the intern’s short interview. Dalakuriren’s assistant editor-in-chief had placed a basket of celebratory pastries on the news director’s table.

Once the task force had arrived in their black combat suits, the scene was transformed. The rescue command from Falun had to move away from the shaft, there were new cordons, and heavy boxes made of reinforced plastic were lined up on the yellow grass next to the edge of the mine’s entry. The Stockholm divers checked their oxygen tanks, and the TV cameras captured how fit bodies slid into rubber and neoprene.

The Falun police stood like spectators with their arms crossed as the first pair of divers started to lower themselves into the mine, and when they reemerged, there was no time for them to react before the National Task Force commander arranged his own improvised press conference. The journalists gathered in a flock around him under the floodlights. The freelance photographer held up the camera with his arms straight up, aimed it down, and got a picture of someone with close-cropped hair, whose face was furrowed and resolute.

“Okay, listen. Let’s get some things clear,” said the commander. “We understand that some of you from the media have started to issue reports before you even know what we’re dealing with.”

“Are we supposed to ask permission or something?” interrupted a reporter from the state channel, which had done live reports based on Dalakuriren’s information at 6:00, 7:30, and 9:00.

A guy from the big evening paper also became angry:

“What we’re dealing with? What do you mean what we’re dealing with? We’re dealing with a woman who was murdered way down in a mine shaft, and that’s all we’ve said. That’s what the guy who found her said.”

“Well, listen,” said the commander. “I don’t know how you all got that information. But let’s start from the beginning. For one thing, that’s no woman down there in the shaft.”

The journalists squirmed.

“Like I said, not a woman. It’s a man.”

The intern felt something cold trickle down his spine. Then he heard himself protesting: “But it was a girl! That’s what he said, the guy who found her.”

“I don’t know who you’ve been talking to,” the commander said curtly, “but the body down there, it’s a man. And that man has been dead for several days, maybe longer, maybe much longer. So this is what will happen. Before our divers bring up the body, it will be wrapped, so that we can safeguard forensic evidence. You should all try to remember that none of us knows anything about why this man is dead. According to our divers, there’s nothing that points to a murder.”

“Is there anything that indicates it isn’t one, then?” ventured the intern. The commander’s jaw tightened, and it looked like he was planning to answer. But then he wrapped up instead:

“That’s all, thanks, and you guys should try to keep to the facts from now on. We’re going to move our cordon out into a circle of about two hundred yards, out of respect for any next of kin. So you can start packing up.”

But, despite the blockades, the next morning both of the country’s evening papers showed the picture: a man’s corpse being lifted out of a mine shaft, wrapped up to the chin in the task force’s body bag. His long hair framed a bloodless face, and the flash from the camera had illuminated the whitened strands into a wreath of light, like a halo. But what the buyers of this issue would presumably remember most was the deep notch that had been cut just above the bridge of the man’s nose like a third eye socket.

3

The Æsir Murder

It had been a very quiet morning meeting at Dalakuriren’s long center table as they worked through the list of potential follow-ups and, more important, decided who would do the job.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!