Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

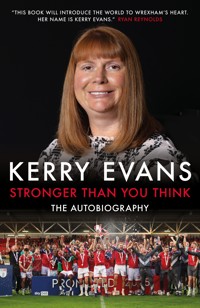

"THIS BOOK WILL INTRODUCE THE WORLD TO WREXHAM'S HEART. HER NAME IS KERRY EVANS." RYAN REYNOLDS Before they purchased Wrexham AFC, Hollywood stars Rob McElhenney and Ryan Reynolds were told to contact two people: footballing legend Dixie McNeil and Kerry Evans. When Kerry received that call from California, something inside her sparked at the words 'Would you like to come on a journey with us?' Born with cerebral palsy, Kerry battled indifferent doctors, relentless bullies and crushing anxiety to establish the life she'd dreamed of. At thirty, she suffered a near-fatal brain bleed, leaving her without feeling on her right side and unable to walk. From rock bottom, Kerry fought to get her life back. Everything changed when she became Wrexham's disability liaison officer… and then Hollywood came calling. Stronger Than You Think offers a unique insider perspective on Wrexham's star-studded takeover, with first-hand insights into how two famous actors altered the fortunes of the club and the community surrounding it. But this isn't just the story of Wrexham AFC. This is the story of how one woman's indomitable spirit enabled her to overcome the odds stacked firmly against her and make an immeasurable impact on the lives of football fans with disabilities and their families.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 399

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

ii

iii

iv

v

Nan, you were literally my world.

I simply adored you.

I wish you were here to read this – you’d have read it in a day!

Love you always xx

vi

Contents

Foreword

BY RYAN REYNOLDS

I’ve been asked to write a foreword. I assumed that meant, like, a paragraph. Maybe less? A brief statement or simple grunt. But then I was told the story was Kerry Evans’s – and suddenly, just a paragraph felt like a bit of a d*ck move. I’m sure she asked Rob first. But everybody knows Rob likes to draw pictures. In crayon. Which makes his worth in the exciting and delicate medium of a foreword useless as f*ck.

So here I am. Vulnerable, inspired… unpaid. And perhaps worst of all, outmatched by the courage, humour and soul of the woman you’re about to meet.

Let’s start at the beginning. Not Kerry’s beginning – you’ll get to that in Chapter One. I’m talking about the other beginning. The moment two Hollywood schmucks showed up at Wrexham AFC. (Not naming names, but only one half of this partnership actually LIVES IN HOLLYWOOD. Because of my devotion, I’ve been living at the stadium for the better part of a year. Only Chal knows. And the player that shall remain nameless – you know who you are – who brings me Nando’s every Thursday.)

Where were we? Ah! Yes. The other beginning. The schmucks xinevitably came a-knockin’ on Wrexham’s door. Just like the prophets foretold. The prophets, in this case, being me and Rob McElhenney. (Note to reader: Rob’s last name can – at times – be tricky. We all call him ‘Rob Mac’. But on Welcome to Wrexham, it’s McElhenney.)

As we secretly sashayed our way through the town and its inhabitants, we soon met a disarmingly candid Welshman named Spencer Harris: part-time martial artist and full-time wonderful husband, father and friend.

And then he picked up the phone to someone with whom we’d later share the unlikeliest of phone calls. ‘Kerry, we’ve had a request,’ Spencer began. ‘Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney want to speak to you.’

Now imagine you’re Kerry Evans. You’ve lived through enough drama to fill ten biopics and a 348-episode order of CoronationStreet. You’ve battled systemic apathy, endured eye-watering physical trauma that only a woman of peerless mental discipline could withstand and yet still found a way to give other disabled Wrexham fans the opportunity to attend away games. In short, Kerry’s story doesn’t need a Canadian movie star and an American pantomime showing up to make things feel any more cinematic. And yet… hi!

When Rob and I first heard Kerry’s name, it came with the canonised respect reserved for saints, superheroes or Canada’s official moustache, Robert Goulet. ‘You need Kerry onside,’ someone told us. It sounded strategic. But what they really meant was: you boneheads need Kerry to remind you what the hell this is all for.

So we called Kerry. We Zoomed over a thousand Wrexham fan owners. We tried our best to seem chill. Rob probably rehearsed for days, possibly weeks, before these meetings. To project power and intelligence, I wore a jet-black turtleneck I’d stolen from Spencer Harris’s bedroom when I got ‘lost’ looking pourletoilette. xiTurtlenecks make no sense. It’s like having your torso attacked by Steve Jobs if he was made of molten hot lava.

But when Rob spoke to Kerry? Kerry was calm. Curious. Controlled. She asked questions. She listened. And when Rob said: ‘Would you like to come on a journey with us?’ he sensed the flicker in her eyes. Not just of hope, but of someone who’d spent a lifetime hauling coal out of dark mines and crushing it into diamonds. She knew, instinctively, a door had creaked open. A door of opportunity for those that opportunity had, effectively and openly, excluded.

Kerry won’t say anything remotely close to self-aggrandisement. But it isn’t aggrandisement if it’s a simple, elegant truth: she was already the soul of Wrexham long before we ever showed up.

This book is the story of that soul. And while I’m tempted to describe it as ‘inspirational’, that word feels too small, too polished and trite. Like a label you slap on a quote above a beach photo. Plus, I don’t know how to read.

Kerry’s story isn’t inspiration. It’s ignition. It lights something inside yourself – a belief that no matter what your body does or what the world says, you can manifest the impossible. You can build systems of kindness, connection, impact and togetherness.

Kerry never set out to be famous. All she ever wanted was to help one person. Just one. The irony, of course, is that she’s helped hundreds, if not thousands. Probably you, by the time you reach the end of this book.

Football is at its best when it transcends the sport and reveals something bigger. And for me, that something is ‘togetherness’. When people walk into the STōK Cae Ras, they check their identity politics at the door. They’re wearing the same shirts, waving the same colours and they sing and chant the same songs. It’s one of the xiifew spaces we have left where we come together with no intention of hurting each other. Just winning. Or drawing. Or losing with some grace. It is far and away my favourite place on earth. It’s my FieldofDreams.

Wisdom like Kerry’s is a hard-fought prize. Earned by her willingness to engage in a moment-by-moment showdown with herself. And Kerry has transcended what it means to make spaces inclusive. She’s also made space for the one person she wasn’t expecting: herself.

In this book, you’ll read about a girl who, when shoved by pain, shoved back. A mother who weathered storms, too many to count. A volunteer who became a changemaker. A Wrexham supporter who found, in football, the thing she’d always given others: belonging. And that, at least to me, is the essence and the perfection of the beautiful game.

It’s time I hand the mic over to Kerry. Read this slowly. Absorb each page. Because while WelcometoWrexhammay have introduced the world to this football club, this book will introduce the world to its heart. Her name is Kerry Evans.

Ryan Reynolds

Wrexham AFC Co-Owner

Unlicensed Blanket Folder

Very Lucky Human

Prologue

‘We’ve had a request,’ begins Spencer Harris, the director of Wrexham AFC. It’s 7 November 2020. I’m in the lounge, watching early evening TV.

I remember the date because what happens a few days later – who calls me, and where they call from – will be so extraordinary that I’ll mark the moment with a Facebook post. It will amount to no more than one line in the sea of words written about Wrexham AFC amid one of the most extraordinary takeovers in world sport. But I don’t know that at the time. I don’t know of all that is to come: the Emmy award-winning TV show, the international headlines, the Hollywood superstars that we will welcome to our club. I don’t know of the effect that it will have on me, a voluntary disability liaison officer with cerebral palsy who is weeks away from working for one of the biggest names in the film industry and a very successful American TV star.

I sit in shock, listening intently as Spencer continues. ‘Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney want to speak to you. Am I OK to give them your phone number?’xiv

I pause, lower the phone from my ear. ‘Well, yes,’ I stutter. ‘Yes, of course.’

These are the moments I look back on, over four years into our football fairy tale, when I wonder how we got here. How I, little old Kerry who began volunteering at Wrexham in 2016, became swept up in all of this. How a non-league football club in an unglamorous area of North Wales, which survived for years only on the generosity of its fans, became the luckiest team in the world.

£12 a year. That was how much it cost to be a Wrexham owner in 2020, and there were more than a thousand of us. Together, we made up the Wrexham Supporters Trust (WST). No matter how much money you put in – the equivalent of £1 a month, as I did, or £1,000 a year – everyone had the same say. Nobody was more of an owner than anybody else and, crucially, each of us had a voice.

Aside from managers and players, the club employed just a few full-time members of staff: the groundsman, stadium manager, commercial manager, shop and ticketing staff, club secretary and head of youth. Everyone else had full-time jobs elsewhere and ran the football club as volunteers.

There was the six-person Wrexham AFC Board of Directors, comprising fans overseeing all the day-to-day logistics. They looked after the money, sorted the deals for new players and held all the secrets. They answered to the Wrexham AFC Supporters Trust Board: twelve elected fans who acted on behalf of all fan owners. Spencer Harris, a strategic director at Kellogg’s, was the public face of the club and the one who would put his head above the parapet. We didn’t have a full-time CEO; the role was divided between the directors, all unpaid. We held ownership meetings quarterly to discuss the direction of the club.

Wrexham was almost an after-work hobby. We held meetings in xvthe evenings and sorted out the odds and ends at weekends. That was how the club ran for twelve years.

At the time, I was a big fan of our model of fan ownership. I thought it was incredible. Here we were, still a big, identifiable club throughout North Wales, even in the National League, doing it on our own in the spare time people grabbed between work and family and life. Volunteers were running the football club out of duty and passion. I really respected that. Ultimately, it was why I joined. It was why I built my own role up from a part-time one to the equivalent of a full-time job, without earning a penny.

But the model had its drawbacks. It’s only now, with the benefit of hindsight and Hollywood money, that I’ve realised how limited we were. There was never enough money in the pot, so the same story kept repeating itself: the minute we had a special player, we had to sell them because we needed money to run the club. We also had to pay what those in the boardroom call ‘the National League premium’ – that little bit extra to encourage players to drop out of the English Football League.

On top of that, the National League (the fifth tier of English football) is a tricky division to get out of, in part because there’s only one automatic promotion spot (League Two has three, and League One and the Championship have two). In 2011, a haul of ninety-eight points – then a record for the club – wasn’t enough to get us promoted automatically. Increasingly, we found ourselves coming up against clubs with rich owners and bigger budgets. In 2013, we were beaten in the play-offs by Newport County, bankrolled by a former mechanic who had won the Euromillions. Salford City had won promotion in 2019 funded by Manchester United’s Class of ’92.

We knew that we could never go out and buy the top striker or the best players, and a divide was building between those who were xviwary of welcoming new owners at the expense of losing fan control of the club and those who thought it was time to try something different.

During the pandemic, the stakes were higher still. Put simply, we didn’t know where the money was going to come from without supporters coming through the turnstiles or sponsors paying for the advertising hoardings. First team players were furloughed and had to take on extra work, in supermarkets or as delivery drivers, to support their families. On the field, the curtailed 2019/20 season ended with the club’s lowest result in 156 years when Wrexham finished twentieth in the National League.

Most nights, I went to bed filled with anxiety over the future of the club. I knew the players and their families. What would happen to them if they lost their jobs? What would happen to us without Wrexham? I still received my state benefits throughout the pandemic, but my work was never about money for me.

Wrexham AFC saved my life. I don’t mean that I would have died had the club not come into my life, but it found me at a time when I didn’t know what my purpose was. After a cerebral bleed that could have killed me in September 2005 but instead left me in a wheelchair and without feeling down my right side, I’d left the workplace and woke up every day in pain and with no reason to get out of bed. I didn’t have an identity or know what to do with each day. I never thought I’d work again. That bubbly Kerry who had always refused to let her cerebral palsy hold her back felt like a distant memory. I was a shell of myself again, back to being that lonely teenager who never thought she’d be accepted or make anything of her life.

Wrexham brought the world to me. That’s how it saved me.

Take my 2018 fundraising to put on accessible away travel for xviiwheelchair users. I sold red blankets emblazoned with the club crest to raise the £3,500 we needed to cover several away fixtures that season. My husband Kings and I had ordered 680 blankets, each individually wrapped, and spent our evenings in the living room unpacking and repackaging them all: the club’s kit suppliers, Macron, had offered to embroider Wrexham’s crest at a cut price if Kings and I took care of all the packaging for them. At the first fixture we offered our accessible travel to, against Solihull Moors, grown men were in tears because they’d never been to an away match before. En route to a London fixture, we met up with other coaches of fans at a service station, and when everyone started chanting together, I knew it had all been worth it.

Those interactions are what keep me at Wrexham: the families I meet and the impact I have on them. I’m proud that I’m good at the work I do there. I’m proud that, every day, I do things I never thought I’d be able to. And I’m proud of the effect my efforts have on the club’s supporters.

I owe a lot to Wrexham. That club is everything to me. And it could have gone under were it not for the discussions taking place in the background – discussions with two Hollywood superstars on the other side of the Atlantic.

There had been twelve approaches to buy Wrexham in the eleven years since the club went into the hands of the Wrexham Supporters Trust. We heard all the rumours – businesspeople, conmen, entrepreneurs, opportunists – but nothing ever came of them. If the interest had been serious, the WST would have put in place NDAs and the prospective buyer would have had to put up a bond of £5,000. That protected us from chancers and scared off the pretenders. As far as we knew, no NDA was ever signed in all that time.

This time was different. The rumours began: an offer had come xviiiin for the football club. A serious offer – so serious that it was being discussed among the board members. Every day, there were whispers, mutterings. I pulled aside somebody in the know and spoke to him off the record. The gist? ‘This is big.’

As far as names went, though, the rumour mill was as silent as silent can be and I was none the wiser. Until I got the phone call. I was in the kitchen, preparing our tea, when the phone buzzed. It was someone else inside the club.

‘Do you want to know the name?’

My heart stuttered. My voice hitched. ‘I’d love to,’ I began. ‘But I know I’m not supposed to.’

For a second, I doubted whether I truly wanted to know. With a fan-owned club, everyone had big mouths and loose lips. People knew everything, even if they weren’t supposed to. And there was leak after leak after leak. I’ve never, to this day, disclosed anything confidential to journalists or on social media. But at a small club, you’re always under suspicion. ‘You were there. You were in that meeting,’ they’ll say, or ‘I told you this – who else did you tell?’

Did I want to know? My mind toyed with itself. Say I found out. If those names ever got out prematurely, the club could turn around and point the finger at me. I knew I wouldn’t go to the press, but I didn’t want the blame thrown my way if somebody else did.

I paused, suspended in that breath between knowing and not knowing. OnceIfindout, I thought, therewillbenogoingback.

‘No, don’t tell me,’ I said. Then I changed my mind again. ‘No. Go on.’

‘Have you… have you ever heard of Ryan Reynolds?’

‘Not on your life!’ I shouted. ‘Ryan Reynolds, going to buy Wrexham AFC?’

‘It’s true!’ they protested. ‘He wants to buy Wrexham – with Rob xixMcElhenney, from AlwaysSunny.’ I turned to Kings, my husband. He nodded: he’d watched Rob’s show, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, about a run-down Irish bar in the US.

‘You’re having us on.’

‘I’m not, Kerry,’ they insisted. ‘Think about it. Where would I have dreamt that name up from if it wasn’t true?’

They had a point. If you’re winding somebody up, you’re not going to come out with Ryan Reynolds buying Wrexham, are you? You’d aim your sights a little bit lower. My mind scuttled through all the other names we’d heard over the past few weeks. Robbie Savage had come up a lot. He had been born in Wrexham and played locally before joining Manchester United as a trainee once he finished school. Back when he was a player, he’d talked about the possibility of ending his career at Wrexham or one day managing the club. Russell Crowe came up, too, because his great-grandparents, Fred and Kezia Crowe, had run a fruit and vegetable wholesale business from Wrexham. Social media had declared Crowe a dead cert. I’d never seen Gladiator, but that would have been exciting enough.

This?

Kings and I spent the rest of the night laughing at each other in disbelief. The news didn’t sink in because it was just too silly. How could we believe it? Why would Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney buy a football club in Wrexham? A rich businessman would have been one thing, but even that would be nothing like whatever this was.

I was desperate to tell people, but that information never went any further than Kings, who always knows what’s happening, and my dad, because he doesn’t have social media and I trust him completely. If I’d been in that insider’s position, I wouldn’t have breathed a word.xx

It meant that Kings and I had to carry on with day-to-day life for the next few weeks, burying the secret. We spent half that time looking at each other in disbelief. No,itcan’tbe.Itreallycan’tbe. Every so often, we had to stop what we were doing and allow the thought to flash through our minds: RyanReynolds.

In late September, the names were made public. At an emergency meeting on 22 November, the WST voted to allow sale talks to go ahead with people they’d only known as ‘two extremely well-known individuals of high net worth’. The day after, the club released the names.

Fans reacted exactly as we did: Don’tbesosilly.Thisisawindup.Itcan’tpossiblybetrue. Everyone knew Ryan Reynolds, but my daughter, Casey, was a far bigger fan of him than I was. ‘This is wasted on you because you don’t realise just how big this guy is,’ she said to me.

Disbelief was on the faces of everyone volunteering at the club. It was the conversation on everybody’s lips: ‘We’re going to work for Ryan Reynolds.’

And we quickly got a taste of what that would involve. We were told very early on that we wouldn’t be allowed to speak to reporters without express permission from the media team. But they quickly became overwhelmed. Overnight, the car park teemed with press. For the next few weeks, camera crews snaked around the stands and reporters doorstepped us as we came and went each day from Wrexham’s grounds, the Racecourse (now the Cae Ras). Journalists raced between the football club and The Turf, the pub next door, which would end up world famous thanks to WelcometoWrexham. Wayne Jones, owner of The Turf, set up a butty van outside during the pandemic, and he and his customers became a goldmine for xxiinterviews. I’d often be stopped by a broadcaster asking for directions. ‘We want to speak to Wayne,’ they’d say, hopefully, their film crews hovering behind them.

I was at the club most days but wasn’t based there because the offices, at that point, weren’t wheelchair accessible. Still, my phone rang constantly with requests from our press officer: ‘Can you come down and speak to ITV?’ Then: ‘Can you come down and speak to the BBC?’

I ended up being their go-to interviewee. As soon as one interview wrapped up, the camera crew from another television channel would be setting up in the background for my next one. ‘What do you think of the takeover? Can we get your thoughts?’

Even at that point, I never imagined how global the Wrexham story would become and how fascinated the world would be with our little football club. Wrexham was home to a very working-class, unassuming community – one that never quite recovered economically from the closure of the pit and steelworks. Pound shops, charity shops and empty storefronts dominated the town centre. There was little investment, few jobs and a population growing frustrated at a lack of prospects. Redevelopment plans seemed to drag on for years and never amount to anything.

But the Wrexham people are very proud of our culture of sticking together. And that culture has been forged, in part, because of the football club.

Many fans were on edge at the talk of new owners. Given all that had happened in the past, they had good reason to be wary. Alex Hamilton, a former lawyer, had arrived in 2000 with his eyes fixed on the Racecourse. At that time, the stadium was owned by Marston’s Brewery and leased to the club. Hamilton arranged for the club to buy the grounds – and hold it ‘in trust’ for his own xxiicompany, Crucialmove. He had opened discussions with B&Q and wanted to sell the stadium and the land around it for commercial development.

By the time Wrexham supporters had driven out Hamilton, the Inland Revenue (now HMRC) had lodged a winding-up petition against the club. It had debts of £4 million, with over £880,000 in unpaid taxes. The remaining directors placed the club in financial administration in December 2004, and as a result Wrexham received a ten-point deduction from the Football League. We were the first league club ever to be penalised under the new rule. The club won its case to keep the Racecourse Ground, though.

The ripples spread outward for years. Wrexham was relegated to non-league football in 2008 after eighty-seven years in the league. Still, there were more difficulties to endure.

Ahead of the 2011/12 season, the Conference League demanded that the club pay a bond of £250,000 or face expulsion from the Blue Square Premier League (now the National League). By Monday 10 August, hours before the payment deadline, Wrexham still owed £100,000. The Red Passion Wrexham message board challenged fans to help the club find the money before 5.30 p.m.

People arrived at the club willing to donate their house deeds. Little kids came with their pocket money. People gave what they could. If you had a spare fiver, you handed it over. It galvanised the town, the fans rallying round with a single-minded focus: let’s keep our club. And by 2.30 p.m., they’d found the money. Everyone says the same thing about their football club, but there really is just something about Wrexham fans. How do they do it, again and again and again? How do they keep defying the odds?

Within three months, the Wrexham Supporters Trust had gone further, and managed to fund the club’s takeover. By asking fans xxiiilike me to pay at least £12 a year to support their efforts, they had recruited almost 2,000 supporters in time to purchase the club at the end of November.

When the pandemic hit, there was a growing feeling that a rich owner might be the only way forward. That view was met with trepidation because nobody at Wrexham has a short memory. We remembered what had happened a decade earlier – and how quickly our club had been sold down the river. But Covid was destroying the club financially.

Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney were our only hope.

• • •

It wasn’t out of the ordinary for Spencer Harris to call me.

‘I’ve got a bit of a strange request for you, Kerry.’

‘All right.’ In my voluntary role, I was used to strange requests. I was endlessly fundraising, begging and borrowing to find the money we needed to make the club accessible for as many fans as possible.

‘Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney want to speak to you,’ Spencer says. ‘Am I OK to give them your phone number? I wasn’t going to do it without asking.’

‘Well, yes,’ I stuttered. ‘Yes, of course.’ I was aghast. I couldn’t say no, but I didn’t get it – why would they want to speak with me?

‘It won’t be somebody calling on their behalf,’ Spencer continued. ‘One of them will contact you to have a chat. And I don’t know when they’re going to ring you, but it will be soon.’

I turned to Kings. He had muted the television for me to take the call and noticed my stunned expression. ‘That was a mad one,’ I said. He watched, my hand shaking, as I dialled my dad. I had to share this with him.xxiv

‘You’ll never guess what,’ I said. ‘Spencer Harris has just called. He’s passing on my number to Ryan or Rob.’ I held the phone away from my ear as I heard Mum screaming.

‘What?’ gasped Dad. ‘Why? What do they want with you? When are they going to ring you?’

It was arguably the most important question, and as the days passed with no call from the US, I kicked myself for not asking Spencer that very thing. Why hadn’t I? It was so unlike me: if I needed to know something, I made sure I found out. Why had I been so quiet this time? This was the biggest thing to happen in the club’s history, and I’d only gone and kept myself in the dark. But the shock of it all had made it hard to know what to say.

We waited. Every time my phone chirped, I’d jump slightly, then my heart would slow when I realised it wasn’t them. I spent my days in apprehension and suspense, planning and rehearsing what I’d say to them. But there was only so much preparation I could do when the one thing Spencer hadn’t said was why they even wanted to speak to me. I replayed the conversation over and over in my mind, trying to remember exactly what he’d said: Ryan or Rob have asked if they can contact you. What did that even mean?

We waited. I didn’t tell anyone at the club that I was waiting for a call. All I knew was that no other volunteers had spoken to our prospective owners.

Still we waited. Every day, Mum rang. ‘Have you heard anything?’

‘No, I haven’t. And you don’t need to ask! The minute I do, I’ll call you.’

The more time went on, the more I wondered if they weren’t going to phone after all. Perhaps they just didn’t need to speak to me anymore. Maybe they’d never needed to in the first place and someone had made a mistake. After all, I was only the voluntary disability xxvliaison officer – I didn’t hold all the purse strings. And Spencer had been short on the specifics. All I could do was wait for my phone to light up with what I assumed would be a withheld number.

Late one evening. I finally heard from them. I wheeled myself into the lounge as Kings flicked through the channels on the TV. My phone buzzed.

I looked over at Kings. ‘It… It says California on the phone,’ I breathed.

‘Get lost,’ he chuckled.

‘Kings – it says it right there.’ I held the screen up to him, my hand shaking again.

‘Well, you’d better answer it then, before he hangs up.’

I reversed, pulling through the lounge into the dining room.

‘Hello?’

‘Hey! Is that Kerry Evans?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s Rob McElhenney here.’ An absurd thought struck me: It’shelpfulthathesaidhisname. I wouldn’t have known what either of them sounded like.

I swallowed, forcing out my reply. ‘Thanks for ringing,’ I managed. ‘How are you?’

‘I’m good. It’s so good to speak to you.’

Yourvoiceisshaking!I snapped at myself. I could feel my throat closing up. In all my imaginings of this call, all my thousands of rehearsals and practice runs, I’d never been this nervous. I never thought I’d sound so stupid. I looked over my shoulder to see Kings loitering in the archway, craning his neck to hear.

Rob explained that he’d spoken to Wrexham’s board about the important people he and Ryan needed to get onside before the takeover. In response, the board had given him two names. The first was xxviDixie McNeil, the Wrexham legend who became club president in 2013. The second was mine. My name, he said, had come up again and again. He used the word ‘unanimously’.

‘I hope you don’t mind me calling,’ he said. ‘Spencer Harris gave me your number.’

‘Of course.’

‘You’re obviously aware we want to buy Wrexham.’

‘Yes.’

Rob knew a lot about me and what I’d created at the club. He knew of the fundraising I’d done to put on accessible away travel for wheelchair users. He knew about how I’d turned a derelict old kiosk, used as an unofficial storeroom, into a sensory room to make our stadium an autism-friendly environment. He knew how, as a volunteer, I’d brought the club in line with the accessibility standards set for higher division clubs. He knew that I was looking to set up a powerchair football team for wheelchair users. He and Ryan had clearly done their homework, whether aided by the board or Google.

‘You’ve done absolutely fantastic things for the club regarding disability,’ he said. He was so down-to-earth that it felt as though I’d spoken to him before: he felt familiar, somehow, even though I’d never seen AlwaysSunny. I felt calm, at ease. This was the most extraordinary phone call of my life, but it felt so… normal.

‘Thank you very much,’ I said. ‘I love what I’m doing. It’s an absolute honour to do the job that I do.’

It was true. I could see the impact that my work had on the lives of our supporters, and that always made me want to do more. I thought of the dad who’d only ever been able to take one of his twins to Wrexham matches because the other had autism and couldn’t cope. Our Quiet Zone had meant that they could all go together. xxviiThe dad had been in tears as he told me: ‘I don’t think you realise how big it is for me to bring both of my boys to the football.’

‘I can’t believe you did all that as a volunteer,’ Rob continued.

‘It wasn’t easy, but being given the opportunity by Wrexham was enormous to me,’ I explained. ‘I didn’t ever think that I could achieve what I have.’

‘We’re going to back you up with anything you want,’ he said. ‘We’ll back you all the way.’

My mind raced with the possibilities. Everything I’d delivered at Wrexham to that point had been done on a shoestring. I thought of the quiz nights I’d held, the raffles I’d run, the locals I’d asked to chip in out of the goodness of their hearts, all to scrape together the money we needed. ‘Yes, you can do it, Kerry,’ the board would tell me whenever I came to them with my latest idea, ‘but you’ll have to sort the funds.’

Someone coming in with Hollywood money would change everything. It hit me: we would be able to move mountains with this kind of backing.

Rob explained that he and Ryan were holding a Zoom call with all the fan owners the following evening. He wanted to mention in the meeting that we had spoken and that they were fully behind the amazing job I’d done. He asked my permission to do so.

‘Yes, of course,’ I said. ‘I’m an owner. I’ll be on that call.’

‘Well, we’ll see you tomorrow night,’ he said. ‘Ryan and I are very excited about getting our story out to the fans. Hopefully, it will go our way and we’ll end up buying Wrexham AFC. So,’ he paused, ‘are you up for coming on this journey with us?’

My hand shook as I tapped out an update to Facebook: ‘It’s not every day you get a call from Rob McElhenney from Hollywood.’xxviii

Chapter One

Mum Knows Best

This is the story my parents have told me about my birth for as long as I can remember.

My mum, Susan Jones, was admitted to hospital to be induced when I was a week overdue. She had just one contraction, and after several hours, the hospital staff concluded that I was not ready to be born. They sent her home for one more week.

On 5 August 1975, she entered the hospital again for a second try. Anticipating a long labour, they gave her an epidural and hooked her up to a machine to register my heartbeat. They sent my dad over to the pub across the road, probably with instructions to take his time. The nurses’ view was that nothing would happen quickly.

Mum was in no pain but watched as the machine flashed and beeped.

‘It looks as if she’s in distress,’ she said, concerned.

‘That machine is always playing up,’ replied the nurse, resetting it. ‘She’s absolutely fine. Don’t worry. Take no notice of it. We can hear the heartbeat.’

Soon, it was all systems go. I was born before midnight, a forceps delivery with the cord wrapped twice around my neck but 2otherwise, to my parents’ knowledge, a perfectly healthy baby. Doctors came the next day, took me down to the special care baby unit and later returned me without a word. Mum reflects now that this must have been the point at which they realised I had cerebral palsy. No one ever told her.

I sat up, rolled, crawled and walked on time. The only inkling that something was amiss was when I would press my right thumb into the palm of my hand and clench my fist so tightly that my knuckles would turn purple. I would pull my fist to my chest and my arm would spasm. It was a subconscious movement whenever I was concentrating, whether I was brushing my teeth, playing with blocks or focusing on the TV. My nan – my mum’s mum – would run her hand over mine, feeling for the tightness of the muscles in my hand and wrist. She would massage my fingers with lotions and oils until my grip loosened.

When I was around a year old, Dad was taken ill with appendicitis. Mum sent for Doctor Graham from our local surgery. Dad’s appendix had burst so an ambulance was called. Mum’s recollection of that day is that the doctor spent more time with me than he did my dad. He played on the floor with me, asked me to walk and studied me as we waited for the ambulance to arrive. On my right leg, I walked on the ball of my foot. Days later, he contacted my parents and told them that he would like to refer me to a specialist consultant.

My parents were given no inkling, in the meeting at the hospital, that they would be receiving big news. My dad didn’t even go in; he stayed in the waiting room. Mum went to meet the consultant with me sat on her knee.

‘Well, she’s got cerebral palsy, hasn’t she?’ said the doctor, matter-of-factly.

3There was no build-up, no explanation for how they’d arrived at that conclusion, why they’d wanted me checked out or why they’d asked Mum to bring me there. Mum was hurt that the doctor said this to her as though she’d always been aware, and she wondered later whether ‘cerebral palsy’ had been written in my medical record since birth. She didn’t think to ask this on the day, however. Mum had never heard of cerebral palsy. She didn’t know what they’d just labelled me with or what they were even talking about.

She says now that she is glad that she hadn’t been told when I was just a few days old because she and my dad would have just panicked. As it was, she had been able to enjoy being in the baby bubble without worrying about what the future might hold.

In shock, she stood and took me, on autopilot, straight to have a brain scan. She has memories of me screaming and crying at the noise, the lights and the strangers sweeping in and out of the room – of trying to hold my head in place and soothe me. It was a traumatic day for her and she navigated it in a total daze, confused because she had already seen me walk. She had known I’d had an issue with my hand but hadn’t realised that it hinted at anything like this.

Cerebral palsy is actually the name for a group of conditions affecting movement and coordination, and symptoms vary in their severity. Some struggle with speech, some have learning difficulties and others might be in a wheelchair from birth. Mum didn’t know what the future held for me.

‘Will she be able to dance?’ Mum asked the consultant. She ran the Clifton School of Dance, and taught ballet, tap and modern.

‘She’ll never be able to coordinate easily or skip,’ he replied. ‘She may be able to go to a mainstream school, but it’s too early to say. She might have to go to a special school.’

Mum says the doctor’s next words were: ‘Don’t expect her to be 4able to do anything.’ He told her that I’d never be able to ‘do things other children can’. In the weeks and months afterwards, Mum thought back to the day of my birth and the machine flashing and beeping. She had been right: I was being starved of oxygen.

She was sent away with no leaflets or books. Support was scant. No one had the internet back then to find support groups or look things up. Mum and Dad didn’t know how to access medical journals. All we had were annual visits to a specialist and Mum’s confidence, as she watched me grow, that I would be able to attend a mainstream primary school. My speech was fine – I was so talkative, in fact, that on long car journeys my parents would actually pay me to see how long I could stay silent for.

Aged four, I had an operation to lengthen my Achilles tendon and help me walk more easily. I was unable to put my right foot flat on the floor or flex it, and as a result I’d walk on my toes. I left hospital in plaster, and later had a white plastic splint fitted. It slotted under the arch of my foot and onto my heel and climbed halfway up the back of my calf, fastened across the front with Velcro. My first pair of school shoes were one size too big so we could fit the splint into them. But the surgery didn’t work well, and throughout my childhood I walked with a limp. The limp became more pronounced as I got older, although it wasn’t noticeable until I grew tired. Then I’d trip up. I still have the ripple of the scar down my right leg from where they cut my Achilles and, even though I have no movement or feeling there now, sometimes it will flash purple when stretched or tight.

As I recovered from the surgery, we received a visit from an occupational therapist. Mum had been upset because she had watched me sitting in the window watching the other children play outside.

‘She’s missing being able to be out with the kids,’ Mum said.

5‘I’ll see what I can do,’ said the occupational therapist, and they came back with a red wooden cart. The older kids in our cul-de-sac would call by with the words: ‘Can we take Kerry out in the cart?’ I would sit in it and they pulled me along by the handle. I can’t say I playedwith them at that point, because I still couldn’t climb out, but at least I was with them, out in the street and part of whatever they were doing.

I would see a specialist at his afternoon surgery at a special needs school nearby. I hated going because he stank of whisky. I remember sitting in his tiny waiting room with its three chairs facing the double doors into a gymnasium. The bell would ring and kids went past into the gym in wheelchairs and walking frames. I looked at them and felt lucky that I was able to walk. My cerebral palsy felt very removed from theirs. We used the same words for our conditions, but I would see this horrible man, then go away and come back in six or twelve months. I didn’t need to be there every day.

There were ballet bars on the walls of his office, which also housed a patient bed, boxes with inflatable gym balls and a desk with a big leather chair. He would observe me as I walked up and down, checking my leg movement, getting me to rotate my hips and asking questions about my activity levels. There was never any focus on my hands.

Instead he would measure my legs. He always described my left leg as my ‘good’ leg and the right as my ‘bad’ one. They were significantly different lengths, and his plan was to operate when I turned eight. He would take some bone from my left leg and put it into my right, then do the same again when I turned eighteen. In the meantime, Mum was told to go to Clarks and get a built-up shoe for my right leg.

Mum considered this and wasn’t sure how it would stop me from 6walking on my toes. She asked around and someone pointed her in the way of an osteopath. Mum had never heard of an osteopath but was willing to give it a shot, which was brave of her given she often felt like she just had to do whatever the doctors said. She had heard that things were in motion for my surgery, with the specialist keen to book an appointment to measure me up properly.

The osteopath practised in his house, with a separate door leading to an extension where he and his wife, also an osteopath, worked. From the desk beneath the window, he explained that I was displacing my right leg from the hip bone because of how I was walking.

Behind a screen was a bed fitted with a roll of white paper. The osteopath massaged up my spine with his fingers, remarking that he could feel the tightness stretching all the way to the middle of my spine. He worked by hand, then brought out the massage gun. The pressure increased incrementally, and by the end I was jerking away from him in discomfort. He brought out creams and oils and manipulated my spine and the hip joint.

For the final flourish, he shepherded me over to one side of the bed. I lay on my left side, facing the wall, with my right knee hanging over the bed, and he took my right knee into his hands. Using his elbow, he put his weight halfway down my right leg. CRACK! CRUNCH! The leg shifted back into the joint. As I got up, wincing, he stood behind me, pulled my legs up level with each other and withdrew a tape measure from his pocket.

‘Yep!’ he said. ‘Absolutely spot on. Off you go.’

Mum rightly takes the credit for preventing me from having those unnecessary operations. The initial consultant had just measured my legs, observed that they were different lengths and never looked further to consider the reason: one leg wasn’t sitting in the hip properly. I had never had the full range of movement in my 7right leg and my inability to put my heel down put pressure on my leg. Walking with a limp eventually knocked it out of place.

Mum could tell when I was desperate to have an appointment with the osteopath because I’d be in indescribable pain and walking fully on my tiptoes on my right leg. Most days, I didn’t experience any pain due to my cerebral palsy, but I would feel the difference as time went on between treatments. The constant dull ache would transform into shooting pains into my hip joint that would grow more intense as the weeks went by. When the pain was at its worst, Mum would lie me on her bed and massage me with creams: through my hip joints, where my Achilles had been operated on and the tightest joints in my foot. My arm never brought me pain, but I couldn’t cope with the weight of a saucepan or a heavy book.

We would pull into the osteopath’s driveway and every step up the long, paved garden footpath would be a struggle. I’d come out again an hour later pain free. I could never walk perfectly, but I’d almost be able to put my foot flat. It would take months and months before my leg would get dislodged again and the pain would return. We couldn’t see an osteopath on the NHS and I remember Mum and Dad saying that those visits were expensive, but they were always happy to pay because they knew the treatment worked.