SUNDAY MISCELLANY E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A beloved Irish institution, RTÉ Radio 1's Sunday Miscellany has been woven into the lives of listeners for over half a century. Following on from the bestselling 2023 anthology, this collection brings together some of the best broadcasts of the past three years, arranged in calendar months and moving from spring through to winter. Featuring a spectrum of writing talent, from household names to striking new voices, it offers solace, joy and entertainment for all seasons. Featuring: Jan Carson Niamh Campbell Dermot Bolger Aingeala Flannery Paul Howard Louise Kennedy John MacKenna Rosaleen McDonagh Liz Nugent Joseph O'Connor Olivia O'Leary Glenn Patterson Donal Ryan and many more …

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 630

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

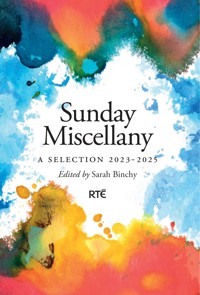

Sunday Miscellany

Sunday Miscellany

A Selection 2023–2025

Edited by Sarah Binchy

Sunday Miscellany: A Selection 2023–2025

First published in 2025 by

New Island Books

Glenshesk House

10 Richview Office Park

Clonskeagh

Dublin D14 V8C4

Republic of Ireland

newisland.ie

Introduction © RTÉ

Individual contributions of essays and poetry © respective authors

The right of the authors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-83594-033-4

eBook ISBN: 978-1-83594-034-1

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Product safety queries can be addressed to New Island Books at the above postal address or at [email protected].

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro on 11.5pt in 14.75pt

Typeset by JVR Creative India

Cover design by Niall McCormack, hitone.ie

New Island Books is a member of Publishing Ireland.

Contents

Introduction

January

Registration of the Birth of Tadhg: Rory Gleeson

Seeing Van Gogh: Jan Carson

After the Hymns: Lani O’Hanlon

Mine Was of Beaten Gold, Yours Was But Black Tin: Conall Hamill

Tentacular Winter: Alexander McMaster

Rain, Clams and the Pogues on Vancouver Island’s West Coast: Mattie Brennan

Mending Our Ways: Margaret Hickey

Getting Away With It: Molly Furey

Saving the Planet in France: Peter Cunningham

Reliving the Life of O’Reilly: Daniel Mulhall

Visible Mending: A Response to ‘The Objects of Love’: Amanda Bell

Sing Like Swallows: Jim Culleton

And Sing Like Swallows (poem): Gavin Kostick

February

At Candlemas: Neil Hegarty

The Move: Beth Kilkenny

The Oystercatcher and St Brigit: Jenny Beale

Cornmeal: Laoighseach Ní Choistealbha

George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue – The Irish Connection: Jim Doherty

The Years in England: Cathy Sweeney

A Prayer for the Electric: Elizabeth Oxley

Among the Trees: Kevin Mc Dermott

And Parnell Loved His Lass: Lourdes Mackey

I’d Love a Babycham: Margaret Galvin

Climbing Carrauntoohil: Jamie O’Connell

Send in the Architects: Leo Cullen

March

Broadway, Baby!: Liz Nugent

At Rest: Alexis MacIsaac

The Wearing of the Green: James Harpur

Ted Fest: Joe Rooney

The Tablecloth: Pier Kuipers

Green: Máire T. Robinson

My Mother and Daniel J. Travanti: Tim Carey

Jung, My Choir and Me: Sheila Maher

Postcard to Annie: A.M. Cousins

The Queen Bee: Rosaleen McDonagh

Oisín in Tír na nÓg: Cyril Kelly

Travels with Lucy: Joe Kearney

April

Passion for the Passion: Bach’s St Matthew Masterpiece: Paul Johnston

Meskel in Lebanon: Louise Kennedy

Easter Miracle: Roslyn Dee

The Batch Loaf: Maeve Edwards

Cocktail Piano Teen Sensation: Conor Linehan

Pet Paraphernalia: Philip Judge

Fiesta Moments: Noelle Lynskey

Feeding the Chickens: Brian Daly

A Café Called Dorice: Oliver Sears

The Trout: John F. Deane

Transporting Bees in Dublin: Kevin Connolly

Bees Honour Their Keeper: Vincent Woods

May

Nests: Kathy Donaghy

Royals and Bloody Sunday: Denis Tuohy

Sally’s Brown Bread: Marion O’Dwyer

The Sea That Defies Time: William Wall

Silent Retreat: Niamh Campbell

The Birdman: Michael Hilliard Mulcahy

The Deburau Effect: Andrea Carter

Imogen Stuart, Rara Avis: Alison FitzGerald

Drinking With My Father: Joe Whelan

St Bernadette’s Lourdes: Impressions of a First-Time Pilgrim: Nuala O’Connor

Novel Suggestions: Bernard Farrell

Fledgling: Kerri Ní Dochartaigh

June

Franz: Hugo Hamilton

Capturing the Flapper Skate: Rebecca Hunter

You Can Never Get Ireland Right: Aidan Mathews

Ways of Seeing: Peekaboo: Glenn Patterson

Seeing Things: Lucy Caldwell

Michael and Me: Billy Roche

Father’s Day: Katrina Bruna

A Street in Belfast: Emily Byers-Ferrian

Black Glass: Gavin Corbett

At the Solstice: Grace Wells

Queen of the South: Paul McVeigh

Horizons: Durgham Mushtaha

July

A Walk Under Trees: Pat Boran

Exposure: Brian Farrell

Home from Home: Barbara Scully

For Vicky: Denise Blake

What Can You Do?: Joanne Hynes

Rule of Three: Pauline Shanahan

Los Perros de La Paz: Niall McArdle

Missy: Mia Döring

Fizzy Drinks: Alan Finnegan

Reading Hemingway: Brian Leyden

Harmonia Mundi: Yvonne Cullen

All-Ireland Sundays with Dad: Éamonn Ó Muircheartaigh

An Citeal: Catherine Foley / The Kettle: translated from Irish by Catherine Foley

August

Islanders: Eimear Ryan

Peig Sayers: The Queen of Irish Storytellers: Nuala Hayes

Olympic Gold: Mae Leonard

Memories of Moscow 1980: John Kirwan

Low First: Colin Regan

Huntin’ the Cattle: Ann Marie Durkan

Fire at South City Market: Antonia Hart

My Home is Thomas Hardy: Michael O’Loughlin

Journey to Judea: Justin MacCarthy

A Walk in the Bots: Valerie Waters

Where the Vegetables Were Cut: Mícheál McCann

September

I’ll See You at the Ploughing: Margaret Dunne

The Kerlogue: Fran O’Rourke

Sun and Air: Nell Regan

Into the Heart of Leitrim: Angela Keogh

My Experience of the Education System: John Forkin

The Buttera: Carol Taaffe

The Kindness of a Stranger: Olive Travers

Showers, Sobriety and Synonyms: Bernadett Buda

Take Comfort in Your Friends: Jackie Lynam

A Pagan Place: Donal Ryan

Great Vowels: Olivia O’Leary

Stardust: Michael D. Higgins

October

The Pyramid of Glasnevin: Cormac Murray

Kurdish Blood, Irish Heart: Zak Moradi

Café, 10.15 a.m., Saturday: Wendy Erskine

The Tea Salon: Eileen Casey

Hartnett Back by the Arra: Mike Mac Domhnaill

The Belfield Bar: Paul Rouse

Great-Uncle Thomas: Kate Carty

A Sheep Dip Saga: Peter Trant

Learning Latin: Tom Ryan

Life Drawing: Sharon Hogan

The Cage of Words: Dermot Bolger

Grey Hair: Antonia Gunko Karelina

November

The Shop: Niamh Donnelly

In Praise of Dark Nights: Kevin Gildea

A Field of Dreams: Remembering Sheila Holland: Mary Hassett

Contagious Egg-centricity: Fiona Hyland

Flights of Fancy: Zoë Devlin

A Very Quiet Mutiny: Eddie Vallely

Paper: Michael O’Connor

Luas Lady: Doireann Ní Bhriain

Gracias Por La Vida: John MacKenna

My Friend the Spy: Justin Kilcullen

The Little Furry Rabbit: Michael Harding

Living in a Ghost City: Aoife Barry

December

Hanukkah: Judith Mok

Annunciation: Enda Wyley

Puccini and the Ghosts of Rome: Joseph O’Connor

Christmas Pudding: Aingeala Flannery

Pork Chops, Peas, Chips and Tea, Bread and Butter: Jim Maguire

I’m Dreaming of the Whites’ Christmas: Jonathan White

Charm of the Capnomancer: Nidhi Zak/Aria Eipe

Harry Kernoff: Fifty Years Gone: Donal Fallon

Deck the Halls: Maggie Armstrong

From Here to the Holy Land: Rachael Hegarty

Back to the Nest: John Toal

A Special Child is Born: John Egan

Night Divine: Paul Howard

Naming the Foals: Grace Wilentz

Human Wishes: Emer O’Kelly

All Things Considered: Gerald Dawe

Contributors

Permissions

Acknowledgements

Introduction

I’m delighted to share this latest collection from Sunday Miscellany with you. It feels like no time since our last anthology, but we’ve already broadcast many hundreds more excellent scripts in that time, from which I’ve made this selection.

Sunday Miscellany is unique in that it has no anchor presenter; writers are not even introduced by name, just credited at the end of the programme. So, you could say it’s a democratic format. You’ll find stories, reflections and poems here from familiar names alongside many new contributors, our year-round open-submission policy lending freshness and variety to the programme.

Listeners tell us that Miscellany gives them a precious hour of entertainment and companionship in their week, and a break from what can feel at times like an unremitting cycle of bad news. Our writers don’t so much shy away from facing the darkness of the world as pay attention to everything that can still bring joy. Our thanks to all our writers and all our listeners, who every week make the programme what it is.

Sarah Binchy

September 2025

January

Registration of the Birth of Tadhg

Rory Gleeson

Recently I travelled two kilometres or so down the road to Camden Registry Office with my rapidly deflating partner and a carrycot filled with something terribly personal, to register the birth of my son. It’s frosty in London, the grass frozen white each day before sunrise. I know this because I am there to witness it, my son having kept me up to do so.

He was born just a week ago, on a Monday morning – purple, screaming, slimy; held aloft by a team of obstetricians, surgeons and midwives who’d vacuumed his head free from my pushing, drugged-up girlfriend, Fedy, my love. I snipped his cord, and they handed him to me, bundled up, before checks, or after, I don’t quite remember, and once they did I rocked him in my arms and looked at his little face and wept, showing him to my also sobbing partner and singing songs to him, between telling him, ‘Welcome, Tadhg, céad míle fáilte, Tadhgy, benvenuto, howiya, ciao ciao ciao my little Tadhg.’

I’m happy to update you that, upon the birth of my child, I have not suddenly become a fount of knowledge about the world. I don’t know anything more about life now than when I entered the hospital. I knew midwives work hard, and I knew hospital workers save us from diseases and ill health. My appreciation has increased, but my theoretical knowledge, no. A week after the birth of Tadhg, I don’t know anything else about being a man, or what it means to be responsible. I don’t know anything about the universe or algorithms or Allen keys or physics or how to make a campfire. Selfish it may be, idiotic it is, but I feel more invested now than I did in the future of the planet, it being the place my child will live.

I am pleased also to report that when walking the streets outside, days after young Tadhg was born, I’m not overwhelmed with some sort of deep change to my own being. I’ve not seen the other side. I have not felt love I have never known, simply a multiplication of something already there. No doubt there is some deeper, more subtle change currently snaking its way into my being, but as it is: nope. I simply have a new, attendant purpose and a set of matching responsibilities. Walking the frost-struck streets of Holloway, I am at times beset by a deep urge to return home, to check on my baby, but I also really fancy a coffee and something chocolatey, and am sure to stress about money while I’m at it. Life carries on, and what’s a baba if not just more life about the place. More screaming, pukey, diarrhoea-ing life.

I have seen my partner happier than I’ve ever seen her. This is bully for her, but it makes my past romancing of her suddenly seem a little underwhelming. Am I to compete with my own child now for my girlfriend’s affection? Yes, it seems. And who will win? Tadhg. But we feel bound to each other now in a way we can’t have ever been before. We’ve given each other a gift, an explosive well of frustration and love. Done a thing together that cannot be undone. Something that can never be changed.

Before I became a father a few short days ago, I saw little point in my interacting with other children, and now, just a few days after, I still don’t. I can tell you I have learned little from my conversations with five-year-olds, and their thoughts are often disjointed, irrelevant or vastly over-simplified. But I respect a parent’s right to show me their child and boast of them, and to adore them publicly. It is their right, and so too now it is mine.

It’s not enough to just register the birth of a child with the relevant authority, Camden Council, or with the GP, for I’ve brought a son of Erin into this world. Though we’re over the sea, and he is a little Londoner by dint of being resident here, as far as I am concerned he’s simply a petite Irishman living in London. He is also un figlio dell’Italia, evidenced by the first part of his last name, and his mother’s eyes so far.

So notice now, to all, that he is Tadhg, a name for me worth roaring to the nation and all its people, whether they care or not. Because delight demands to be shared. An unequivocally brilliant, marvellous, ecstatic thing has occurred, and so, mark these words – Tadhg, my darling boy, is here. So I will sing across the airwaves of his arrival, to strangers and friends alike. One of your nation’s sons is here. Abroad, happy and screaming.

My son looks at me with alien, dark eyes. Face odd, like a little hairless chimp, or a tiny purple bulldog. He coughs and my heart plunges. When he screams me awake at night I dearly wish him gone, and then am shocked at my thoughts in the morning, when this dozing little charmer does all he can to fill my heart with something I can only describe as his name.

Tadhg. Little Tadhg. Taidghín beag. Bello Tadhg-y. My tiny Tadhg-er, my gorgeous boy. I’ll say his name over and over and over only as evidence that he is here, when before I only called him Baba. Now he is my darling son. My excellent little dude.

Welcome to the world, Tadhg. All the better for having you in it.

Seeing Van Gogh

Jan Carson

I’m visiting a friend in Amsterdam. It’s a damp squib of a day. My friend suggests the ‘Van Goh’ museum. I say, ‘here, we pronounce it Van Goff’. I’m quick to side with my fellow Europeans. It’s only six months since the Brexit vote. My friend is an American. He insists it’s Van Goh. And I concede to go with Van Goh. I’m getting in free on my friend’s museum pass.

My friend is a photographer. He’s intrigued by people and the way they photograph things, specifically, cool European things. He’s spent two years travelling round the continent capturing tourists as they photograph their companions posing in front of iconic sites. Buckingham Palace gates. The winter gardens at Versailles. Hands raised like wannabe Supermen next to the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Clambering over the Parthenon. He has little interest in these famous places. Crumbly buildings are much of a muchness when you travel as much as my friend does. It’s the way these strangers see themselves in relation to the buildings which forms the basis of his art.

We’ve picked a good morning for Van Gogh. The museum’s hiving with tourists. All but the intensely earnest – those here to actually appreciate art – are clutching smartphones or wear fancy cameras, strung like pendants, around their necks. To distance ourselves from the Philistines, my friend and I make a complete circuit of the museum, pausing for a discrete thirty seconds in front of each painting. We make appreciative art noises. Hmmmmmm. We pass comment on those pieces we deem especially nice.

I watch a man in a fisherman’s hat move robot-like around the gallery, raising his iPad in front of each painting to snap a photograph. Snap’s the perfect verb for this man. There’s something of the turtle about the way his body leans into the art then suddenly retreats. He doesn’t look at Van Gogh directly. He keeps a protective screen between himself and the art. He could just as easily be observing a solar eclipse; indirectly, for fear of overexposing his eyes. I point the man out to my friend. ‘There are postcards of all these paintings in the museum shop,’ he says. ‘Why doesn’t the man just buy a box set?’ I think of myself, aged six or seven, using greaseproof paper to trace my favourite toys in the Argos catalogue. This was the next best thing to ownership. If I traced a Game Boy or Etch-a-Sketch, it sort of belonged to me. I have some sympathy for iPad man. I don’t mention this to my friend.

My friend stations himself in front of Sunflowers. He photographs the tourists taking photos of themselves with the painting. Mostly selfies on smartphones. I take pictures of my friend taking pictures. I feel very meta. Like I’m in a hall of mirrors. A kaleidoscope of repeating yellows and flesh tones. Approached like this, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers doesn’t look like itself. I’ve seen this painting so many times, reproduced on T-shirts and jigsaws, the original seems unreal, and more so when viewed through a tunnel of screens.

After a few minutes, we’re removed by a security guard. We’re told it’s okay to take photographs of the paintings, but we can’t photograph the people taking pictures of the paintings. My friend says, ‘But I’m making a statement about how contemporary gallery-goers interact with art.’ The guard says, ‘No you’re not.’ We are not looking at the paintings in the appropriate way. I don’t know much about Van Gogh. I’ve watched one documentary. Read a few articles. Still, I’m pretty certain, Van Gogh was not a big believer in the appropriate way of looking at things. Do I bring this up? I do not. The security guard has clearly had enough of us.

We’re escorted out of the museum. I’m a little thrilled by this. Though inappropriate art viewing is hardly an arrestable offence, I’ve never broken the law before. (Except when I stole a teaspoon from Costa Coffee researching a story about kleptomaniacs. Guilt-ridden, I returned the spoon the following day.) For once I feel like a proper artist, sticking it to the man.

In the pub, afterwards, my friend and I discuss the state of the world. The way real life no longer feels real until it’s captured on a smartphone and plastered over social media. ‘People’, my friend concludes, ‘have lost the art of being present. They’re so intent on recording everything for posterity, they’re not actually in the here and now.’ I agree. I also wonder where this leaves us. I pin everything down with words. And my friend reconfigures the world through his camera lens. It’s our way of seeing. And understanding. It’s how we take ownership. Are we really any different from the selfie-snapping tourists, forcing ourselves into every frame?

After the Hymns

Lani O’Hanlon

Me and Annie walking out into the dusk after choir practice, the ice-pop-orange lights along the driveway coming on one by one.

The sound of tyres first, skimming across the tarmac and then skidding to a stop in a show-offy way, Gerard Sullivan and Mossie McCabe with others I don’t know. They begin to circle us. The vinegary scent of chips mingles with the scent of candle wax and incense on my coat, my Christmas coat, and my new boots clinging to my calves.

‘Hey, boots,’ Mossie calls out. Skids to a stop in front of me. ‘Do you want a chip?’

The left side of his face is in shadow so I can’t see the twist in that eye. Annie says that it’s a glass eye. But I don’t think so. Astigmatism the optician called it, said I had slight astigmatism in my left eye but it’s not as pronounced as his.

The chip bag is warm, the last of the chips soggy down the end of the bag. The acidy vinegar shoots up my nose.

Gerard is offering a neater-looking bag of chips to Annie. Gerard was my first boyfriend, came to my house when we were only eleven with a present, a chain with a small cross studded with blue glass. He’s nice, Gerard, a good boy, not like Mossie, who is walking beside me now, stopping to lean the bike against his thigh so he can wolf down the last of the chips.

Mossie’s brother Fran has been in prison and his mother drinks.

The others fade back into the dusk. Gerard and Mossie cycle slowly along with us through the lanes and roads of our housing estate. Annie gets onto the crossbar of Gerard’s bike and they wave as they take the turn for her house. Her family are what my dad calls ‘holier than thou’, and her mother says that my skirts are too short. Annie wears dresses her mother made and I thought that she would never get a boyfriend, but her eyes are such a deep blue and her eyelashes are spider-leg long. Of course Gerard likes her.

I’m alone in the dark with Mossie and he’s walking me home and there is no one home because our shop opens late on a Thursday and my little sister Ellie goes there after school.

‘Well, see you then,’ I say at our sidewall in the lane.

But he drops his bike and hops over the wall with me, walking me around the back where it is very dark. I wonder if he is going to try and ravish me with hard and insistent lips like the men in my mother’s novels?

‘Eh, goodnight then,’ I say as I jump through our unlocked back door into the kitchen. The Superser gives a familiar rattle. He jams his foot in the door like a pushy salesman, grabs my hand and pulls me back outside.

His lips on mine are soft, not hard at all. His army jacket smells of vinegary chips; he pulls away a little and looks at me, not smiling, taller than I thought.

He reaches into his jacket pocket and takes out a small box of chocolates.

‘A present for you.’

Then he’s gone.

When I’m coming in from school the next day, Dad comes through the kitchen, followed by Mam.

‘Who’s Mossie McCabe?’

‘Just a friend of Gerard’s.’

‘Well, his mother was here earlier,’ Dad says and he’s smiling to himself; Mam joins in, ‘standing at the front door in her fur coat, ranting and raving.’

‘Why?’

‘Said her son is a little tyke, and we should keep you away from him.’

‘I don’t know him very well.’

‘Well, maybe steer clear of him all the same,’ Dad says.

Our scruffy poodle, Dixie, follows me up to my box-room bedroom and leaps onto the bed.

I lift the chocolate box’s crinkly sheet to expose the chocolates, each in its own self-shaped nest.

Next day I pass his gang on the street. Gerard breaks away from the others, tells me that Mossie’s mother has locked him up, that he had a split lip when he called out from his bedroom window.

Nights I lie awake, thinking of him, the way the twist in his eye makes him look like he’s trying to figure something out. I wait, but he never calls. I save the chocolates until they turn white.

Mine Was of Beaten Gold, Yours Was but Black Tin

Conall Hamill

The annual New Year gathering in his aunts’ house at Usher’s Island hasn’t really been going too well for Gabriel Conroy, the main protagonist of James Joyce’s short story ‘The Dead’. The evening has largely been a series of gaffes and upsets: he has managed to offend Lily, the caretaker’s daughter, with a throwaway remark about her love life; he realises too late he has miscalculated the tone of his after-dinner speech, a mistake from first to last, an utter failure, he thinks; one of the guests, Molly Ivors, accuses him of being a West Brit because he has no interest in the Irish language. Worse still, he has been unmasked as a regular contributor to, of all things, the Daily Express.

Then, just as he is preparing to leave at the end of the party, he sees his wife, Gretta, pause at the top of the stairs and lean on the banisters to listen attentively to one of the guests singing in a nearby room. Gabriel doesn’t realise it yet, but the earlier setbacks of the evening are about to pale into insignificance compared to the revelation that will be prompted by the decision of that guest, Bartell D’Arcy, to sing the heartbreaking ballad ‘The Lass of Aughrim’.

Richard Ellmann, Joyce’s biographer, claims that the slightly ungracious and self-important tenor Bartell D’Arcy of the story was based on the well-known singer Barton McGuckin. McGuckin was born in Dublin and studied in Armagh and Milan before joining the Carl Rosa opera company. Various accounts of his life relate that he achieved a number of firsts: Derek Walsh notes that he was involved in the first broadcast of an opera in Ireland in 1883 when a telephone device connecting the Gaiety Theatre to an adjacent room allowed a large crowd to hear him sing in Il Trovatore. Nuala McAllister Hart, writing in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, says he was the first Irish singer to make a phonograph recording when he recorded Thomas Moore’s ‘Avenging and Bright’ in 1903.

Barton McGuckin flits in and out of the newspaper columns of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Given that Joyce describes his fictional counterpart as being reluctant to sing at the aunts’ party because of a cold (‘Can’t you see that I’m as hoarse as a crow?’ says Mr D’Arcy roughly at one point), it’s a curious coincidence that one of these newspaper appearances is in an article headed ‘What They Take For Their Voice’. It’s an account of how well-known singers and actors staving off sore throats protect themselves from bugs that might affect their performance. ‘Madame Trebelli has a penchant for strawberries,’ we are informed. ‘Madame Malibran’, on the other hand, ‘drinks half a bottle of champagne with her dinner half an hour before going on stage.’ Our hero, however, cuts a more sober and ascetic figure: ‘Mr Barton McGuckin carries with him strong smelling salts to ward off incipient colds,’ the paper informs us tersely.

His name also appears in connection with a case in the Dublin courts, Waters v McGuckin. A widow, Mrs Waters of Charleville House, Dundrum, took an action against McGuckin to recover a valuable diamond ring from him that had belonged to her husband. McGuckin claimed that her husband had given him the ring as a token of his admiration while on board the Etruria on a voyage to New York in 1887 – a gift he had repeatedly refused, as he had more valuable rings than he knew what to do with, he maintained. Despite his protests, Mr Waters had insisted on pressing the ring into his hand before disembarking and so McGuckin reluctantly accepted it. The case was eventually settled in favour of the widow: McGuckin was forced to return the ring.

This ring-as-a-token incident provides yet another curious overlap between fiction and reality. The song ‘The Lass of Aughrim’ exists in many forms across Ireland and Scotland. There’s even a lighter French version from Brittany, where it is known as ‘Germaine’. A husband returns from the Crusades after seven years and his disbelieving wife demands proof of his identity. He produces the broken half of his wedding ring that matches perfectly the other half she has kept safely while he was away – and, naturally, because they’re French, they live happily ever after.

But just as Barton McGuckin found himself in some difficulty because of a ring, so too does the girl in Bartell D’Arcy’s song: most Irish and Scottish versions are songs of betrayal and rejection. In a version collected in Tyrrellspass around 1830, the callous Gregory challenges the poor lass who calls at his house with their child on a miserable night to establish her identity:

Oh, if you be the lass of Aughrim,

As I suppose you not to be,

Come tell me the last token between you and me.

She replies:

Oh, Gregory, don’t you remember

One night on the hill,

When we swapped rings off each other’s hands, sorely against my will?

Mine was of beaten gold, yours was but black tin.

As with Gabriel Conroy at the end of ‘The Dead’, it’s about discovering that the person you loved, and may always love, is not quite who you thought they were.

Tentacular Winter

Alexander McMaster

Have you ever been stung by a jellyfish? It’s a nasty experience, but it’s just the beginning.

There is an idea – jellyfish apocalypse theory – which suggests that, in a lifeless ocean, swarms of gelatinous creatures will be all that remain. Ghosts, lingering in the void left by the squids and the sea stars, nudibranchs and narwhals, jellyfish will be the shadow of consciousness in a dark blue sea … fluid packs of neurons throbbing to the beat of their own directionless march. Nothing left to sting.

Warming seas hasten the jellyfish apocalypse, offering a hospitable habitat for their hauntings. They thrive in the oxygen-poor oceans of the future. The jellyfish judgement is near.

This gooey horror is one that humankind will probably avoid, as part of the extinction cohort. But we do like our dystopian fictions, and jellyfish make a suitably unagreeable anti-hero. They are just irritating enough, their translucent beauty surpassed by the reputation of their sting. And in the past decade they’ve dropped hints at world domination. A Swedish nuclear reactor risked overheating when its cooling system was obstructed by a jellyfish swarm in 2013. The same fate befell a US warship that drifted for days off the Australian coast as jellyfish blocked its engines.

They are shapeshifting, volatile, threatening global security with their soggy mass.

But I have started thinking about jellyfish in more affectionate terms: as gentle observers who accumulate an elemental wisdom of the sea. I grew up by the Atlantic in northwest Donegal and it is here that I have had most of my jellyfish encounters. I found one washed up on the sand, an inky globule coloured with such purity that it appeared to be a distillate of the ocean itself. A blue elixir that was certain to possess alchemical magic.

I became so entranced by jellyfish that I started to learn their patterns, and my days were governed by the same tides that might bring them ashore. My fixation grew from hyperlink to hyperlink as I tumbled through web pages: box jellyfish have a set of twenty-four eyes and might be older than dinosaurs; there is a jellyfish capable of immortality; there is a jellyfish that weighs Two Hundred Kilos. I contemplated getting a jellyfish tattoo on my lower leg.

But as is often the case with runaway obsession, reality slapped me on the face. Or rather, a jellyfish did.

I was swimming hard on Marble Hill Beach in Sheephaven Bay. Fixated on my own stroke, I barely saw it sweep by, dark stripes radiating from the edges of its smooth body.

Compass jellyfish. Strikingly horrible.

The pain of the sting came slowly but it grew rampant. It started at my mouth and cut along my nose, screaming in the groove of my upper lip. I thrashed towards the beach and ripped off the goggles that had saved my eyes. The sunlight blinded them shut.

Gripping my face, I tried to squeeze out the pain. Jellyfish tentacles are made of tiny stinging cells that hook onto the skin and inject a potent neurotoxin. I staggered along the beach. I cursed the damned creature as its poison seeped through my nervous system, pain edging down my neck and my spine. Swearing, stopping, breathing hard, my head grew light with panic. There were lifeguards at the other end of the beach and I lurched towards them, but then felt ashamed to be making a fuss about a mere jellyfish sting. I slumped onto the sand, head clenched between my legs.

Vicious, nasty creature. Did it not understand how I revered it? Was my deep curiosity so easily unappreciated? I had shrouded its ugliness with mystery, constructed a version that captivated my thoughts. I had presumed to set the terms of our relationship. Had it all been in vain?

Wikipedia told me that some jellyfish are capable of consciousness. Have they no capacity for empathy? Even if they do, what would they care? They’re going to rule the world.

After some time, the ache in my back eased, and I opened my eyes. A plain reality seeped in to replace the shock. I had pursued my own selfish interest and the jellyfish had responded in the only way it could. Humans are curious; jellyfish sting. This one had taken control of my body, as it and its companions will do the oceans. There is no way to escape the jellyfish apocalypse. They are coming for us.

The best remedy for a jellyfish sting is seawater, so I returned to the shore and swam past the break line, wary of another attack. Awe and fear are not unalike. My fantasy had lasted a few short weeks of summer. All gone with a single callous sting.

Rain, Clams and The Pogues on Vancouver Island’s West Coast

Mattie Brennan

‘Tuff City Radio: your home at the end of the road,’ drawls the local radio station’s DJ in a raspy whisper. He croons the long O sounds, releasing the words onto the airwaves as though they should have a sticker attached that reads ‘Caution: Fragile’.

Tuff City Radio is a tiny independent station in Tofino, a town on the west coast of Vancouver Island, Canada. It’s eclectic in its output. Free from the commercial pressures of nationwide or city-based radio stations, it eschews contemporary chart music and plays whatever it pleases, whenever it wants. Sometimes their DJs cut a song short if they feel it’s trundling on too long. Sometimes they’ll shift from a southern blues number to an epic psychedelic track .

Years ago I visited Tofino, a small, famed surf town, with the intention of spending a month there, but in the end staying nearly a year.

This place grabs you, right? is what the people there said. Venturesome Ontarians who have traded the Great Lakes for the Pacific Ocean; restive Manitobans who have fled the vast plains of the prairies for the beaches and tree-blanketed mountains; disillusioned Albertans who have swapped oil-money trucks for beaten-up camper vans. The inhabitants of the place are diverse as a Tuff City Radio playlist.

When winter settles in the rain comes, as inevitable as the tides. Deluges fall in biblical swathes. Unlike home, though, no talk of bad weather is tolerated unless a particularly destructive storm is arriving. Daily chit-chat relies on other subjects: surfing, mainly; ice hockey when the play-offs commence; but seldom the weather.

‘Will it ever stop raining?’ I asked one of my co-workers one November day. We stood inside the door of the surf shop looking out at the rain as it was slavering from the maw of a massive grey cloud.

‘We’re living in a rainforest, it’s bound to rain,’ he replied. He wasn’t being sarcastic. He was matter-of-fact, showing a forbearance towards the downpour that I found unfathomable yet impressive. Don your rain jacket, slip into your wellies, and just get on with things: that’s the Tofitian way.

And so the rain lashed against my sitting-room window throughout the winter, and Tuff City Radio droned on my small alarm-clock radio that – in lieu of a TV or Wi-Fi – was my sole entertainment system. After some time, I noticed that I had heard very few Irish acts on the station. I almost grew homesick for Bono’s voice.

One night, early in the New Year, my friend Luc, an Albertan who had grown up hunting and fishing, invited me to dig clams with him and his friend Carlos. Carlos belonged to the Toquaht First Nation, an indigenous people whose home reservation lies deep in a secluded inlet of Barclay Sound, an hour from Tofino.

The night was cold but rainless. The tide was low. We were careful to avoid digging on native land, skirting the border and ensuring we dug only in permissible territory. The moon was covered by a pall of impenetrable clouds, so we found our way using torches. After gathering the clams, we plucked oysters from adjacent beds and Carlos told us that, in the past, warring tribes would use the beds as a kind of torture instrument. A captured warrior would be dragged on his back across the shard-like shells.

Afterwards, we brought a portion of clams and oysters to Carlos’s auntie, who lived with her husband in a timber-framed bungalow on the reservation. She was a petite, curious woman and, before my arrival on her doorstep, had never met an Irish person. She invited us to have a drink with her. Over the hours that followed, we drank several more.

I sat in the warm sitting room observing the artwork adorning the walls, eating home-cured candied salmon, drinking cans of Bud, listening to Carlos’s many stories. He had travelled a lot. He had recently spent some time gallivanting in Mexico until, as he put it, he grew sick of himself and returned home to settle down, to finally grow up. I nodded along to everything he said – I could relate.

Carlos’s auntie lamented the loss of a pet dog. A predacious wolf had clenched it and stolen it away to the forest. She was worried now that her other dog would meet the same fate. Carlos told his auntie that he would shoot the wolf, but only if she really wanted him to. For a wolf, he said, was a noble creature.

Sometime during the night, I was gifted a wooden mask carved by Carlos’s cousin. It’s on my bookshelf now, watching over me as I write.

Then Carlos’s uncle-in-law played the Pogues on YouTube, and the cosy bungalow in Barclay Sound along the 49th parallel suddenly felt like one near the Ox Mountains. It was even further than the end of the road of which the Tuff City Radio DJs spoke but, finally, I heard some music that reminded me of home.

In the morning, as we drove away on a rutty logging road, the gleam of the rising sun dazzled the water of the Sound. A gentle wind riffled the branches of the Douglas firs. Canadian geese filed by in the bay. It didn’t rain that day, either. But for the days that followed, the weeks, the rain fell as though the sky had been sundered.

Mending Our Ways

Margaret Hickey

In the world I grew up in, the concept of decluttering was unknown. In our house we had less than a dozen of anything, including cutlery and eggs. I knew exactly how many pairs of socks I had and a new dress was a treasure I would try on often, but wear only for best. My mother knitted our woollens and on the hearth was a red-and-black rag rug made with strips torn from an old coat. It fell to my father to mend our shoes and a couple of times a year he’d bring out the iron last and assemble his paraphernalia of nails and rubber soles and heels, plus little kidney-shaped metal segs that extended the life of a heel even longer. (What a pity none of us could tap dance!) I never felt deprived, because why would you, if you had enough? The motto ‘make do and mend’ was one we lived by quite happily.

So, when did repairing things become quaint? No one in today’s throwaway society darns a sock or sews on an elbow patch. In my childhood, there was a general expectation that furniture and kitchen appliances should last a lifetime. Deep down, I still feel that way and I love my 35-year-old vacuum cleaner, although I accept that if my washing machine breaks down, it may cost more to repair it than to buy a new one. Built-in obsolescence has seen to that.

Of course, not everything is disposable. We all still hope to repair major items. Cars, farm machinery and electronic goods all come to mind. For a time back there it looked as if big business would make it impossible for anything to be repaired other than by the original manufacturer. However, both in the USA and in Europe, Right to Repair legislators have brought in measures so that your local mechanic and electronics repair shop get a fair crack of the whip.

As we become increasingly aware of the damage our non-stop consumption is causing, there’s a recognition that we need to recycle, re-use and repair. Over fifteen years ago, the first Repair Café appeared in Amsterdam, and since then, thousands of Repair Cafés have sprung up worldwide. These are places where you can bring in your broken toaster and walk out with it under your arm, all fixed. Some places are stocked with tools and people show you how to use them, while in others, volunteers donate their skills on your behalf. Instead of twiddling your thumbs while you’re waiting, it is only decent to return the favour, if you can. Perhaps you’re handy with a sewing machine or have a knack with bicycles. I’m not immune to the siren call of shopping, but I find the fix of buying new doesn’t last long compared with the satisfaction of getting your knife sharpened instead of throwing it away.

The Japanese have a particular contribution to make to the whole repair idea. When a ceramic vessel is cracked, or even if a piece is missing, they repair it with liquid gold or liquid silver or else a special urushi resin lacquer, into which they’ve mixed powdered gold or silver or platinum. So when a crack in a tea bowl is repaired, the repair is not hidden but made apparent and becomes a thing of beauty in itself. A golden zigzag runs down the bowl, as if it’s been touched by celestial lightning.

This art is an ancient one, dating back to the late fifteenth century. The story goes that Ashikaga Yoshimasa cracked his favourite tea bowl and sent it to China to be repaired. Alas, when it came back the pieces were held together by big metal staples, which made it look as if a giant locust had clamped itself on to the vessel. Japanese craftsmen were stimulated to look for a more aesthetic way to repair and they devised kintsugi, a word that translates as ‘golden joinery’.

To the Japanese mind, repairing an object marks an event in its history and celebrates it, making it more precious. Kintsugi is similar in attitude to wabi-sabi – the Japanese philosophy of embracing the flawed.

If we look at repairing in this light, we see it for the creative thing it is. My dad, in his messy old shed stocked with hammers and rusty tins of odd washers and screws, could take a wobbly chair and make it as good as new. Better than new, because it now embodied his loving skill. He was doing more for the planet than we knew.

Getting Away With It

Molly Furey

Before I moved away, I never thought about how the Irish cross the road. It’s not the kind of thing that you think about, and it’s certainly not the kind of thing that you think has any national character. But then I moved to Amsterdam. A city where the people are an obedient, unfussy kind. The sort to not question a rule, to enjoy a good system. The sort to wait for a red man even on an empty road.

When I first moved to the Dutch capital, a professor advised me that one of the great difficulties of settling into the city would be ‘adjusting to its rhythms’. I wondered when it was that he’d last tried to set up a bank account or secure health insurance with the Dutch. The rhythms of a city! Spoken like a true academic!

But I found myself recalling his words in the weeks that followed – usually when I was crossing the road. I was out of sync with the rule-observing Dutch. My impulse to anticipate a traffic sequence for myself earned me disapproving looks from my fellow pedestrians, and one too many close shaves with outraged cyclists.

The Dutch have little time for notion-taking. They’re a straight-talking people who make plans and stick to them. You offer them a cup of tea and they will answer truthfully and directly – they’re not expecting you to cajole a yes out of them, and get very irritated when you try to do this.

I admired the seamlessness of their way of life when I first arrived. ‘They’re very efficient,’ I’d report home. ‘Buses arrive as scheduled and oh, they hate nothing more than a queue!’ I was a parody of any Irish person to have ever moved there. I was sure that any displacement I felt could be quickly redressed by a cup of Barry’s tea or a sneaky pint.

I was surprised then by how reassured I was by the language of Dublin pedestrian life upon my return home. I found myself struck, maybe even charmed, by chancers waving down cars as if it was their God-given right to cross precisely where and when they wanted to, calculating traffic sequences as if it was some kind of puzzle waiting to be solved, as if the traffic lights weren’t specifically there to do all of this work for them.

In my wistful state of return, I found something poetic about the excessively long time the orange man bleeped on, a seeming acknowledgement of the specifically Irish understanding of this signal, which we take to mean ‘speed up’ rather than slow down. In fact, how Dubliners crossed the road seemed to capture all that I had actually missed while I was away – and it was nothing a cup of tea or a pint could ever have replicated.

Only in coming home did I realise that what I had really missed in all that time was the feeling of ‘getting away with it’. Just the possibility of it made me giddy again. For all my efforts to achieve the cool coherence of the Dutch, I’d been yearning for that wiggle room – the go on, go on, whatever you say say nothin’ of it all. Rules are made to be bent here. It’s why we lose our minds at an all-you-can-eat buffet, slipping croissants into our pockets as if an apocalypse might strike before lunch. I mean, it had been over a year since a stranger had winked or rolled their eyes at me.

So these days I soak up the swagger of those who have just bent the traffic sequence to their will; the smug satisfaction of someone already walking across the road as the green man lights up. Witnessing these jammy victories has been the ultimate restoration since moving back.

I love now getting to blitz past tourists who have stopped, oh so earnestly, at an orange man. I relish the in-joke satisfaction of knowing exactly when you’re good to chance it on Thomas Street, or in understanding that there is simply safety in numbers when crossing O’Connell Bridge. I love ‘getting away with it’ again; recognising the eye-bulging, brow-raising, ‘Jaaaysus’ look of it all. The rhythm of the place, I suppose.

Saving the Planet in France

Peter Cunningham

My friend Jack is in love with EVs. He’s infatuated. He recently bought a big SUV, all-electric, needless to say. This was no ordinary set of wheels. Jack boasted that it had a range of 550 kilometres, even 600. Belfast and back, easy, he said, unbelievable range.

EV drivers are range obsessed. The driver of a traditional car doesn’t immediately start to brag to you about how far the car can go before it stops. So, when Jack said he was driving to France for two days and invited me along for the spin, the first thing I asked about was range. He looked at me. France is coming down with charging points, he said, but we won’t need them! We’ll get over and back on the charge I’ll put in at home.

In slanting sleet a few days later in Cherbourg, we disembarked from the ferry and headed for Mont Saint-Michel, a journey of just under two hours. The dashboard battery icon read 95 per cent. Our windscreen and rear window de-misters were on full, as was the heater, the heated seats, the GPS, the radio and, of course, the lights and the windscreen wipers. Jack wasn’t hanging about. If he knew that on motorways, EVs drink battery like thirsty camels drink water, he never showed it. He powered us down the rainswept highway, as the on-board map screen showed the nearest EV charging points. Dozens of them. Why did I feel so nervous?

Our B&B didn’t have a charging point, and although EVs can be trickle-charged with a normal plug and cable, a process that can take more than half a day, why worry when we still had 61 per cent and were in a country with more charging points than mushrooms?

Next morning, after a leisurely start, in a public car park not far from Mont St Michel, we spotted a charging point. The plugs at EV charging stations can differ. Here, two cars were already using the machine, so Jack decided to leave it until we came back from seeing the sights; but, after a good lunch, we found two different cars using the machine. Shouldn’t we wait, I asked? No need, Jack said, come on, let’s go – and stop worrying! Our battery was at 50 per cent.

There is some discussion as to what exactly happens when an EV’s battery runs out. There’s a difference, it seems, between flat and dead flat. ‘Your EV is not just going to stop in the middle of the road’, said an article when I Googled the subject. ‘The car will do everything it can to get you to a charging point.’ Ah, that cleared that up then.

We drove up the coast of the Cotentin Peninsula, checked into our new lodgings and set out to find a charging point. It was eight at night. The battery icon said 23 per cent. We followed the GPS and arrived at a shopping centre. It helps no one to repeat the language used when Jack realised that this particular charger plug was not compatible with his car. So we bought wine in boxes and returned to our digs.

Next day, on 19 per cent, wearing overcoats, we set out driving very slowly for Cherbourg. No heater, demister, lights or radio. Guided by the screen, we detoured to a tiny hill village, Les Pieux. It was raining heavily as we crawled uphill and eventually found a rusting, yellow EV charger behind the town hall.

Many EV charging points won’t take your credit card until you first download an app. Standing beside Les Pieux’s corroding charger, as rain trickled down under my collar, I rang a number on the box and explained to someone that we hadn’t time to download an app because we were rushing to catch a ferry. No dice, monsieur, a man’s voice said. You must download the app. He then hung up.

We resumed our journey, without speaking. Jack tried not to check his dashboard. ‘If the battery runs out, the vehicle will go into preservation mode,’ the car’s handbook said. ‘Remain calm.’ In Cherbourg, we were the last vehicle to board. The ship’s charging points were on another deck. Our battery was at 6 per cent. We headed for the bar.

Calmness was a challenge next morning as we slunk out of Dublin Port and entered the north bore of the Port Tunnel on 3 per cent. A terrifying vista loomed. A major traffic incident. Suddenly a robotic voice inside the car began to shout: ‘Urgent! Stop the car! You have no battery remaining!’

But we drove on, in my case, in terror, as the robot continued to bawl its warning. At walking speed, we joined the M50, and chugged along for five more kilometres until, glory be to God, we eventually rolled up to Jack’s house.

‘See? I told you we’d do it on one charge,’ he said with a sheepish grin.

I want to save the planet, I really do, I thought as I got into my beautiful, reliable diesel banger and fled, but surely, surely there must be easier ways to do it.

Reliving the Life of O’Reilly

Daniel Mulhall

I can still recall the excitement my wife, Greta, and I felt as we set off for a new life in Australia in 1985, with a baby and a toddler in tow. We were bound for Greta’s home city of Perth where I was to teach at a university. During the two years I spent in what locals call WA, I came to love the wide-open spaces of that vast territory, similar in scale to the whole of western Europe but with a tiny population of just over one million at that time.

I took a particular interest in Western Australia’s rich Irish connections, epitomised by Clareman Paddy Hannan, who discovered gold there in 1890, triggering the last great Australian gold rush and setting off a mining boom that continues to this day.

Then there was the Irish engineer C. Y. O’Connor, who was responsible for building the Port of Fremantle and the water works that supplied the burgeoning mining communities of Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie at the turn of the nineteenth century. Today, O’Connor is memorialised with an equestrian statue on a Perth beach that now bears his name.

After two happy years in Perth, Greta and I returned to Ireland so that I could resume my position in our diplomatic service. In the years that followed, we continued to return to Perth as often as finances would permit. We paid our most recent visit to mark my retirement and Greta’s significant birthday.

Travelling up the coast from the wine-producing area of Margaret River, on a quiet stretch of road on the shores of the Indian Ocean, in a grove of trees I came across a memorial that highlights another Irish connection with that faraway land. It remembers the Fenian John Boyle O’Reilly, who was born in County Meath on the eve of the Great Famine. He was involved in newspaper work in Ireland and Britain before joining the British Army. O’Reilly was convicted of recruiting servicemen into the Fenians and was transported to Western Australia in 1867. The cell he occupied in Fremantle Prison can still be visited, but the indomitable O’Reilly did not remain there for long.

Aided by a local Irish priest, Father Patrick McCabe, O’Reilly escaped on board an American whaling ship and made his way to the United States, arriving in Philadelphia in November 1869. He subsequently settled in the Boston area, where he continued his involvement with Irish nationalism, working with fellow Fenians to organise the celebrated rescue of six Fenian prisoners from Western Australia on board the Catalpa.

O’Reilly’s writing and editorial skills stood to him in his new home. He became the editor and owner of the Boston Pilot, at that time the leading Catholic newspaper in America. He did a considerable service to Irish literature by publishing regular essays by W. B. Yeats, in which he elaborated some of the ideas that powered the Irish literary revival of the 1890s. The fee of a pound for each article when it arrived through Yeats’s letterbox was always a welcome source of financial relief to the impecunious young poet.

O’Reilly became a prominent figure during America’s gilded age, befriending the leading American writers of that time, Longfellow and Emerson. His sympathies ranged well beyond the concerns of Irish Americans, and he argued for improved conditions for workers and for fairer treatment of African Americans during the repressive Jim Crow era that followed the American Civil War. One of his best-known poems celebrates Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Native American extraction who was killed during the Boston Massacre of 1770, which triggered the American War of Independence. For the egalitarian O’Reilly, ‘there was never a separate heart-beat in all the races of men’.

John Boyle O’Reilly also praised the exploits of the Irish Brigade at the Battle of Fredericksburg, ‘who charged for their flag to the grim cannon’s mouth’. I have visited that Civil War battlefield and seen for myself how brave the Irish needed to be to run up that hill under intense fire. With an inclusiveness typical of him, O’Reilly recognised too the valour of those Irish who fought on the Confederate side. His conclusion was that: ‘Who loveth the Flag is a man and a brother, no matter what birth or what race or what creed.’

John Boyle O’Reilly was just 46 years old when he died in 1890 of an accidental overdose of sleeping medicine. His death was widely mourned, and his funeral was attended by the US president, Benjamin Harrison.

During my visit to Western Australia, I had a further brush with the O’Reilly legend as I watched Ireland play Scotland in the Rugby Six Nations at the John Boyle O’Reilly pub in a Perth suburb, complete with a replica of the rowing boat in which he made his initial escape. I found myself surrounded by a new generation of Irish exiles totally different from those O’Reilly wrote of in his poem ‘The Exile of the Gael’, whose songs, he said, were ‘saddened by thoughts of desolate days’. In an exuberant throng of young Irish toasting another Irish rugby triumph, there was no hint of Desolation Row on that balmy night in Perth.

Visible Mending: a Response to ‘The Objects of Love’

Amanda Bell

A couple of years ago there was an exhibition in Dublin Castle called ‘The Objects of Love’. It gathered together memorabilia, left behind by the family of Oliver Sears, which was brutally dispersed in Nazi-occupied Poland. I wrote this piece in response to the exhibition.

Consider textiles: the warmth of a woollen jumper, the comfort of cashmere, the airtight insulation of fur. Consider how uniquely human it is to fabricate clothing and wear it.

Consider then the process of removing everything that distinguishes a person as human, that deprives them of their humanity, reduces them to a number.

Consider the Nuremberg Laws.

Consider being banned from visiting parks, restaurants and swimming pools; from owning radios, records, or telephones; from riding bicycles and from keeping pets.

Consider being ineligible for clothing ration cards; being forced to hand over all garments made of wool and fur.

Consider how cold it gets in central Europe, and being forbidden to wear anything but woven textiles.

Consider the flax fields of Poland, the vast expanses of blue-flowered plants dancing into the distance.

scythed green sheaves –

the stench of retting fibres

catches in my throat

the rattle of seedpods

golden streams of linseed

spill into trailers

coarse strands of flax

coiled around the distaff –

the clanking of looms

Consider the city of Łódź, the country’s largest centre for spinning, dyeing and weaving linen.