9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

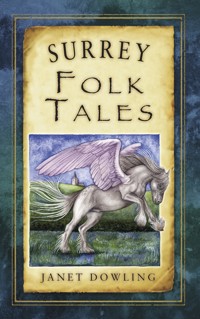

Surrey's landscape, shaped by the Devil's mischief and the whims of dancing Pharisees, is home to a wealth of tales. For Surrey is a place where dragons have stalked, dripping poisoned saliva from their yellow teeth; a place where horses have sprouted wings in order to rescue bewitched villagers; a place where pumas with the gift of speech have prowled the countryside. From the legends of Stephen Langton to the marvels of Captain Salvin and his flying pig, Janet Dowling has vividly retold these myths and stories of Surrey, and brought to life the county's heroes, villains and saints.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

To the memory of my uncle, Alick Anderson, who was the first storyteller who sparked in me a love of stories. As a six-year-old child I sat at his feet while he regaled us with tales of his adventures travelling the world, honouring the folk tales from Australia, New Zealand and the North Americas.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Map

1 The Dragon of West Clandon (West Clandon)

2 St Martha and the Dragon (Chilworth)

3 How the Giant Sisters Learned About Cooperation (Chilworth)

4 How the Power of a Dream and a Pike Created a Great Man (Guildford)

5 The Fair Maid of Astolat (Guildford)

6 Captain Salvin and the Flying Pig (Whitmoor)

7 The Treacherous Murder of a Good Man (Hindhead)

8 How the Devil’s Jumps and the Devil’s Punch Bowl Came To Be (Churt and Hindhead)

9 Old Mother Ludlam and her Healing Cauldron (Frensham)

10 The Revenge of William Cobbett (Farnham)

11 Mathew Trigg and the Pharisees (Ash)

12 The Surrey Puma (Waverley)

13 Not So Wise Men

The Hermit of Painshill (Cobham)

Cocker Nash (Waverley)

14 The Golden Farmer (Bagshot Heath)

15 The Curfew Bell Shall Not Ring Tonight (Chertsey)

16 Edwy the Fair, and the Dastardly St Dunstan (Kingston)

17 The Loss of Nonsuch Palace (Cheam)

18 A Dish Fit for a Queen (Addington)

19 The Mystery of Polly Paine (Godstone)

20 The Rollicking History of a Pirate and Smuggler (Godstone)

21 Rhymes, a Riddle, Poems and a Song!

Sutton for Mutton (Sutton)

Riddle on the Letter H (Leatherhead)

The Tunning of Elinor Rumming (Leatherhead)

The Fairies’ Farewell (Ewell)

Poor Murdered Woman (Leatherhead)

22 The Trial of Joan Butts, So-called Witch of Ewell (Ewell)

23 Troublesome Bullbeggars (Woking and Godstone)

24 The Wild Cherry Tree and the Nuthatch (Surrey)

25 The Pharisees of Titsey Wood (Oxted)

26 The Upside Down Man (Box Hill)

27 The Buckland Bleeding Stone (Buckland)

The White Lady

The Buckland Shag

28 The Anchoress of Shere (Shere)

29 The Legend of Stephan Langton

How the Seeds of the Magna Carta were Sown

The Legend of the Silent Pool

The Flight of Stephan Langton, Aided by Robin Hood

How a Piece of the Holy Cross Came to Surrey

The Barons Meet at Reigate Caves

The Return of Stephan as Archbishop of Canterbury

30 A New Story – Or How Stories Came To Be

Notes on the Stories

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Kathy McClenaghan, Linda Day, Raewyn Bloomfield and Lucy Phelps for coming with me across the Surrey landscapes looking for dragons, giants, witches, and smugglers, as well as murdered men and women.

Many thanks to Mathew Alexander, John Janeway, W.H. Chouler and Eric Parker, who all trawled the primary sources before me and published their own versions of the folk tale material.

Thanks also to Jeremy Harte who, in his own trawling of the Surrey archives, was happy to spot odd bits of Surrey folklore and legend and share them with me, even if he didn’t quite approve of what I did with them, thus maintaining the age-old tension between what a folklorist records and a storyteller retells! Thanks to Alan Moore, Juliette Chaplin and David Rose, who also shared their notes and information. To Irene Shuttle who shared her experience of Surrey folk songs, and to the staff at Halsway Manor who found me a Ruth Tongue story. And to Richard Wood, who helped me when a couple of tales refused to be written.

Many thanks to Lucy and Guy Phelps, Jean and Merv McGee, June Woodward, Margaret Ball, Kim Marks, Samantha Johnson, Robbie and Evan Artro-Morris. They are all from the Chestnut Avenue Book Club, and read and gave feedback on my penultimate drafts; I would also like to thank their children, Nell, Freya, Bella, Karin and Liam, who listened to the child-friendly versions of the tales and gave me good feedback. Plus the newest member of the Chestnut clan – young Megan – who will grow up knowing some of these tales because her mother travelled on the journey with me. This book is dedicated to all six of them, and the children in the schools where I have told these tales. But parents beware – like all folk tales, you need to adapt a story to the ear of the listener or the eye of the reader.

Many thanks to the audience of the Three Heads in a Well storytelling club in Ewell and the members of the Surrey Storytellers Guild, who listened to me telling and retelling the adult versions of the tales. They told me what worked well, and how the stories could be even better if …

Thanks to Lawrence Heath for drawing such divine silhouette illustrations (at the same time as supporting his son Liam successfully prepare for kayaking in the Olympics).

Many thanks to Dianne Symons, Joan Roberts and Fran Andrews for proofreading and challenging me on my grammar, and to Hannah Gosden for her help with The Wild Cherry Tree and the Nuthatch.

And finally, thanks to my long-suffering husband, Jeff Ridge, who supports me in all I do, who also went dragon hunting and searching in caves with me, who drew the map of the stories, and who coped with the writing at midnight and the wringing of hands when all seemed doom, gloom and despondency.

INTRODUCTION

These are the folk tales of Surrey. But what kind of Surrey, you might ask?

Surrey used to be a lot bigger. Before 1889 it extended as far north as the Thames and as far east as Rotherhithe. In 1889, the London boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark and Wandsworth were created and removed from Surrey, and Croydon was made into a county borough. In 1928, Addington moved over to Croydon, and in 1965 Surrey lost more land with the creation of the London boroughs of Kingston, Richmond, Merton and Sutton. Most of these areas retain Surrey as part of their postal address today.

So, back to the question – what kind of Surrey? Conferring with the author of London Folk Tales, it became apparent that she was using the old definition of London and that the South London boroughs might be disenfranchised from representation because they fell between two stools! Thus most of these folk tales come from within the modern-day boundary of Surrey, and four come from the pre-1889 boundary.

Writing a book of the folk tales from your local community is always going to be a challenging journey, and there is a difference between an area you have known as a child and one you enter as an adult. I grew up in the East End of London, and know many stories about that locality. Some are true, some not so true, some are definitely lost in myth and some we might have made up and forgotten that we did so. So it is interesting to come to an area as an adult and look for the traditional stories. But who should you ask, and where?

I have now lived in Surrey for twenty years, and when I asked people what stories they grew up with, they knew very few, and most often told me about the Silent Pool. You will find that one in this book under the legend of Stephan Langton, along with the circumstances under which it was written and the influence it has had on the local appreciation of folk tales. But that was it. Even the members of the Chestnut Avenue Book Club, most of whom had grown up and lived in Surrey, did not know of any folk tales. Indeed, the story of Mathew Trigg and the Pharisees was a complete revelation to the two members who came from Ash, even though the action took place in their hometown.

So where do stories go when they are not being told? This year is the 200th anniversary of the first publication of the Brothers Grimm collection of folk tales. Their first compilation consisted of German folk tales, designed to help German lawyers understand the underpinning values of the law in all the disparate principalities that made the German people. When it became clear that their best-selling market was families, they began collecting more stories, but this time they were not so fussy about where the stories came from originally. So they were happy to collect from their French Huguenot friends, and other stories from around Europe. Furthermore, they trimmed the stories to suit a family audience. They took out some of the sex, cranked up some of the violence (if you were bad, then really bad things happened to you), and then tidied up some of the stories so that they fitted a set structure. In some cases, they completely rewrote them. What started as a faithful reporting of tales as they were told, then became a creative rewriting exercise with intrinsic values introduced and reinforced. How much of this process did I dare replicate? How much should I avoid? I decided that I would have one underlying value – that whatever was told as a Surrey folk tale would have to come from a piece of folklore that was rooted in Surrey. Then I would have to see what happened, but I would be faithful to my source.

So I ask again, where do stories go when they are not being told? They are occasionally recorded in travellers’ writings and old histories of the county – so Aubrey, Cobbett, and Manning and Bray refer to some. I have been fortunate in that local historians like Mathew Alexander, John Janeway, Eric Parker and W.H. Chouler had all published their own reports of the folk tale material. When you know that a tale exists about a particular area, it is much easier to start researching than when you know nothing at all!

As I trawled through the original sources myself, I began to despair about finding something that hadn’t already been collected – they had all been so diligent and comprehensive. But on the other hand, I realised that I would be bringing my skill as a storyteller to the stories – which is why you might find some of my retellings different to how they are reported in the collections of historians and folklorists. Be assured that I have found the original sources, drawn on them, and not wandered too far away! But some of the dilemmas faced by the Grimms suddenly opened up before me, and I could see myself potentially falling into the same traps that they did. The folklorists and historians of Surrey might not be too happy with me. One folklorist provided me with some material about the field names in Titsey Wood and a piece of local folklore. I mixed it with some information about the Site of Special Scientific Interest, and the folklore of the plants found there, to create the story told here. Shall we say that his face was a picture when I retold the story at Three Heads in a Well story club!

Sometimes the stories, like ‘The Dragon of West Clandon’, were well established. I originally knew the story from Alexander’s recounting of it, and I found the original newspaper article which described the solder killing the ‘serpent’ (later known as the dragon), which placed the story in history rather than legend. However, I remained curious to know why he was described as a deserter. I was quite astonished to discover the revolt which forms the first part of the story, which is all true and based on contemporary events which occurred just a year before the newspaper report.

Sometimes I found hints of stories – perhaps just one line. ‘A dish fit for a queen’ is an example of one, where the research brought up a line that said William the Conqueror had assigned to his chef, Tezelin, the manor of Addington, and that the holder of the manor should present a certain dish to the monarch at the coronation. That was all that was said, but in the retelling the rest just fell into place.

Sometimes it was tempting to make up a story. For example, the Hogs Back is a stunning feature in Surrey, and with a name like the Hogs Back there must surely be a story behind it. Even Jane Austen refers to it! But alas, the answer is simply that the expression ‘Hogs Back’ is a geological term to describe a narrow ridge with steeply inclined slopes. Reader, you will find no made-up stories about hogs.

Several years ago I did a project for the Surrey Hills Board, collecting and retelling local folk tales that were suitable for a family audience. The results are at http://www.surreyhills.org/surrey-hills-explore/tales-of-surrey-hills. You will recognise some of these tales here too, but if you compare them you will also notice that the language, and sometimes the content, is different. That’s because I have been telling and retelling the stories in my work with local schools and communities, and, as I have told them, they have developed their own character. I deliberately did not revisit the stories on the Surrey Hills website until I had written my current version of the tales. You may be interested to have a look, to see how much some of them have developed and how much some of them have remained untouched. This is my equivalent of having a first edition and subsequent editions for comparison.

However, there are two stories that I do put my hand up to introducing. I adapted a Chinese tale to explain the presence of the Surrey puma, and my rationale for its inclusion is that I have been telling it for so long in local schools that it has probably made its way into local folklore. And several years ago I deliberately made up another story to show local schools how a true-life event might become a folk tale. I have included it in this collection as it actually came back to me, and was the only story I ‘collected’ from a chance encounter in a café!

There are, I am sure, many more stories out there. In my research notes I have hints of countless more. Alas, my calls to newspapers went unheeded, as I tried to invite people to share their stories. Maybe with this publication, people might be inspired to retell their own tales as well as reclaiming these stories. I invite them to contact me at [email protected].

Some storytellers in this series have numbered the stories in sequence; some have grouped them into common themes, or grouped them so that they reflect the nature of the landscape. I have chosen to put them in a sequence that follows a route around the county, starting and returning to almost the same place. On a sunny weekend you could do your own Story Bike Tour of Surrey!

Janet Dowling, 2013

Numbers on this map identify the general location of the tales and the chapter in this book

ONE

THE DRAGON OF WEST CLANDON

If you drive down the A426, you might just see an outline of a dragon on the local embankment, at the West Clandon crossroads. Be careful, as it can only be seen from the road going westbound to Guildford, and it might be grassed over. But it’s one of a cluster of dragons that Surrey has to offer!

Look there! Can you see? It’s a soldier, on the run in his own country. He looks close to collapsing. He’s as thin as a rake and is scavenging to find something to eat, to fill his belly.

The war with Napoleon was going badly. England hadn’t been prepared for a war so close to its own shores and men were hurriedly recruited to join the army and navy, as well as the local militia. There was hardly any training, and with poor leadership they were sent to fight in France and the Lowlands. When the military expedition to the Lowlands failed miserably, and was followed by the evacuation back to England, the morale of the men was at its lowest. Packed in their barracks at Blatchingford, there was little privacy and, due to the poor harvest, food and provisions were limited. The men were hungry, and 500 of them marched to Newhaven to take the town and find food to fill their bellies. The officers persuaded some of them to return to the barracks, but many stayed in the town and the Dragoons were called out to bring them back. Some men escaped into the countryside, but the men who remained were caught, court-martialled then whipped, transported, or even shot in front of a firing squad.

And that’s how we find the soldier of our story. Cold and wet. Running from his own troops. He knew that he faced a court-martial and possible death, after all he had done for his country. His only thought was to return to his family, possibly for one last time. The only clothes on his back were his uniform, which marked him out as a deserter. He muddied them as best he could to disguise himself, but only succeeded in making himself look more frightening. He had to live on what he could find on the land, as he made his way home.

He slept in ditches and under bushes. He didn’t know the lie of the land, and had to make his best guess, knowing that his home was somewhere north-west. As long as he could see the sun, he could get his bearings. He wasn’t a coward, but he had had enough of the disrespect that was given to a man who fought for his country, and was not given the dignity of food. But now, after two days on the roads, hiding from every passer-by, coach and horseman, he had even less to eat. Berries and nuts do little to fill a man’s stomach. He kept a lookout for isolated cottages, hoping to beg for food there.

His attention was caught by a dog barking ahead of him. He came to a clearing and saw a cottage there. A woman came out with a basket of scraps and threw them to one side. Amongst them he could see a bone with meat on. With no thought except his belly, he scrambled forward to get it, but was beaten by a dog that picked up the bone and ran off. With whatever strength he had left, the soldier was now fixated on that bone and chased the dog. The bone fell from the dog’s mouth, and he stopped to pick it up again. This was the soldier’s chance, and he threw himself on the dog, grasping the bone. There followed a tussle between them, neither prepared to let go, until the soldier suddenly realised what he was doing. He fell to his knees and gave a great wail of despair. Part of him wondered if he would have been better off being whipped, transported or shot.

As the sobs wracked his body, he became aware of a warm wetness on his hand. The dog had placed the bone in front of him, and was licking his hand. The first act of kindness he had experienced in a long time had come from a dog.

The dog stayed; it snuggled beside him at night to keep warm and was a companion during the day. It didn’t take much for the soldier to feel that the dog was his dearest friend and a fine hunting partner for catching the odd rabbit to roast on a fire.

Alas, that’s how he was discovered. The smoke attracted attention and men from the local militia found him. He ran as fast as he could, the dog beside him barking. He was overwhelmed; the militia kicked at the dog and one of them took a club to him.

The soldier was taken to the local lock-up, to be returned to his unit and court-martialled. He knew that his desertion meant he faced certain death by firing squad. His only thought now was for his dog. But no one could tell him where it had gone. There was no rush to move the soldier back. Paperwork had to be done, escorts had to be arranged. It all took time.

While he was in the lock-up he heard a story. A serpent – a dragon – was threatening the people of West Clandon. A huge thing that would block the path, and take small animals. The people were afraid to walk out in the day, let alone at night. Mothers kept their children indoors, and both men and women walked cautiously, afraid to disturb the dragon. Life was greatly disrupted, and yet no one was brave enough to face up to the creature.

Perhaps here was a chance to redeem himself. The soldier sent a message to the local magistrates, saying that he would attempt to kill the dragon – in exchange for a pardon if he was successful. It was an unusual request, but on the other hand, it’s not as though you have a dragon threatening the local community every day.

It was agreed. If he killed the dragon they would make representations for his pardon, for services to the community. They agreed to give him a rifle with a bayonet – but no ammunition. When they let him out of the lock-up, he blinked in the sunshine. He was taken to West Clandon and allowed to go. He was warned that the militia was standing by, and if he tried to escape before fulfilling his end of the bargain, they would hunt him down and shoot him.

How do you look for a dragon? Do you call it? How do you summon it? How do you stalk it? He looked around for evidence of a dragon, going from field to field, sniffing the air. He finally found some pellets on the ground that he didn’t recognise. Could this be dragon spoor? Whatever it was, it was fresh. He was in a field called Deadacre. The field was quite large, and no crops were growing this year. There were several grassy mounds. One mound was particularly large and not quite like the others.

He approached it, and was suddenly aware of an eye in the knoll, that just opened and stared at him. The soldier shook himself, no time to wonder, no time to be mesmerised; this was a time to kill the beast!

He charged with his bayonet, ready to strike, and that’s when the dragon uncurled itself and rose to its full height, towering over the soldier. It had long claws, teeth that were yellow and sharp, and a long spiky tail that unfurled. The soldier suddenly realised that this might not be so easy, but he stood his ground. He was no coward.

He lunged and lunged again at the dragon, but his bayonet seemed to just bounce off the dragon’s skin. The dragon was lashing at him with its claws, and it caught the soldier’s cheek. The pain was so intense that the soldier thought he would faint, but still he stood his ground. Lunge, thrust. Lunge, thrust. Lunge, thrust.

The dragon now towered over him, its yellow teeth dripping with poisoned saliva; one bite could be fatal. The solder thought he was going to die.

Suddenly there was a sound behind him that could make even hell turn over – but he didn’t dare take his eyes from the dragon. Something flew from the side of the field, almost over his shoulder, and fastened itself onto the neck of the dragon. The force of the attack was so great that the dragon tumbled to the ground, and was secured by the weight of its nemesis. The soldier could now see the place where the dragon’s heart was beating just under the skin, allowing him to thrust his bayonet in with all of his might.

There was a soul-curdling cry from the dragon, a shuddering of the torso, and a final lash from the tail. The dragon was dead.

Then another noise. Barking! Still gripping the neck of the dragon was a dog. His dog. His companion. The dog let go and then jumped up at the soldier, greeting him with the joy of a long-lost friend. And they both fell to the ground, laughing and barking.

The soldier was pardoned and the people of West Clandon thanked him for his help. We don’t know if the soldier went back into the army, or whether he did go home, but to commemorate the battle with the dragon a wooden plaque was commissioned that was held in the local parsonage for everyone to see.

Sadly the plaque was stolen, but the people of West Clandon have long memories. A new one was made and is now kept in the Church of St Peter and St Paul. As you go into the church through the north door, just look up and you will see it there.

TWO

ST MARTHA ANDTHE DRAGON

Outside Guildford there is a hill, and at the top of the hill is the most delightful chapel of St Martha. In the evening sun it is a glorious sight, and one of the most beautiful settings in the Surrey Hills. In the winter snow, it stands out and has a promise of comfort for those who make the steep climb to the top. Inside is a standard with St Martha … and a dragon!

A long time ago, St Martha, her sister Mary Magdalene and her brother Lazarus were expelled from the Holy Land, the land of their birth, and sent into the sea in a boat with no sails, no oars and no rudder. They were at the mercy of the sea and the sea monsters. They had no control over where they were taken, or which shore they would be washed up on. Their faith was in the hands of their god and their master, as they were disciples of Jesus Christ.