9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

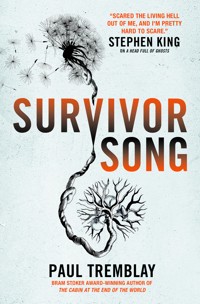

A riveting novel of suspense and terror from the Bram Stoker award-winning author of The Cabin at the End of the World and A Head Full of Ghosts. When it happens, it happens quickly. New England is locked down, a strict curfew the only way to stem the wildfire spread of a rabies-like virus. The hospitals cannot cope with the infected, as the pathogen's ferociously quick incubation period overwhelms the state. The veneer of civilisation is breaking down as people live in fear of everyone around them. Staying inside is the only way to keep safe. But paediatrician Ramola Sherman can t stay safe, when her friend Natalie calls her husband is dead, she's eight months pregnant, and she's been bitten. She is thrust into a desperate race to bring Natalie and her unborn child to a hospital, to try and save both their lives. Their once familiar home has becoming a violent and strange place, twisted in to a barely recognisable landscape. What should have been a simple, joyous journey becomes a brutal trial.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 378

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also by Paul Tremblay and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a review

Copyright

Dedication

PRELUDE: In Olden Times, When Wishing Still Helped

I: They Both Went Down

Rams

Nats

Rams

II: Fill your Knapsack Full of the Sweepings

Nats

Rams

Nats

Rams

Nats

Rams

INTERLUDE: You Will Not Feel Me Between Your Teeth

III: Do you Become a Rose Tree, and I the Rose Upon it

Rams

Nats

Rams

POSTLUDE: No Care and No Sorrow

Acknowledgments

"Survivor Song[is] both an achingly lovely exploration of female friendship and a terrifying race against time. I was fighting tears and gasping out loud and couldn’t put it down."

DAMIEN ANGELICA WALTERS, author of The Dead Girls Club

"Intensely gripping, shocking, and raw,Survivor Songis a visceral ride through a couple of hours of a deadly disease outbreak. Tremblay pulls no punches, but you wouldn't want him to – his characters are real people, and it's the brutal honesty that helps this terrifying song soar."

TIM LEBBON, author of Eden and The Silence

"I love the way Paul Tremblay's books take seemingly familiar tropes and transform them into something fresh and surprising.Survivor Songmay be one of his best – beautifully detailed, viscerally frightening, and deep with emotional resonance."

DAN CHAON, author of Ill Will

"I finishedSurvivor Songlast night and am still shaky in its wake. It’s wonderful – a eerily prescient fever dream, a breathless jolt of adrenaline – a hymn to being human, alive and caring for one another. What a book for our strange times…"

CATRIONA WARD, award-winning author of Rawblood, Little Eve and The Last House on Needless Street

"Survivor Songis a breathlessly compelling read, powerfully frightening and very moving – a nightmare that rings all too terribly true. Paul Tremblay’s strengths grow with every book he writes, and his unflinching imagination enriches our field."

RAMSEY CAMPBELL, author of The Grin of the Dark, Cold Print and many more.

"For the past few years, Paul Tremblay has been setting the standard for modern horror. His genius is that he never forgets the core of a great horror novel resides first in its characters. InSurvivor Song, he revitalizes the zombie novel by keeping the focus narrow and intimate: two women, in the space of a few hours, just trying to get across town. The result is heartfelt and terrifying, in a narrative that moves like a bullet train."

NATHAN BALLINGRUD, author of Wounds and North American Lake Monsters

"A pacy and poignant examination of disaster and grief. It is a mournful, lyrical, and ultimately hopeful lullaby for the living and the dead."

ANGELA SLATTER, author of the World Fantasy Award-winning The Bitterwood Bible and other Recountings

"This compulsive tale of infection and gestation is not just a story of zombie devastation: it is a song to medical ingenuity and to female friendship."

NAOMI BOOTH, author of Sealed and Exit Management

"Brutality spreads in this novel as swiftly as the wild epidemic Tremblay has invented. A daring, terrifying work packed with horror, but also with larger questions about what meaningful survival might be."

IDRA NOVEY, author of Those Who Knew

"Nerve shredding. Paul Tremblay reinvents a classic horror trope for the modern world."

PRIYA SHARMA, author of All the Fabulous Beasts

“Packed full of emotion and suspense,Survivor Songis so gripping it may as well have been glued to my hands. Paul Tremblay is a master of modern horror.”

ALISON LITTLEWOOD, author of The Hidden People

SURVIVOR SONG

Also by Paul Tremblay and available from Titan Books

A Head Full of Ghosts

Disappearance at Devil’s Rock

The Cabin at the End of the World

Growing Things and Other Stories

The Little Sleep and No Sleep Til Wonderland Omnibus (2021)

Leave Us a Review

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Survivor SongPrint edition ISBN: 9781785657863Signed print edition ISBN: 9781789094923E-book edition ISBN: 9781785657870

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UPwww.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: July 202010 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2020 Paul Tremblay. All rights reserved.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Big Business for permission to reprint an excerpt from “Heal the Weak,” words and music by Big Business © 2019

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Lisa, Cole, and Emma

It’s awful and still probably worseThey’re biters and rarely aloneAnd rarely alone.

—BIG BUSINESS, “Heal the Weak”

Author’s note for the reader

When you encounter wide blank spaces and pages, fear not, they are purposeful. Okay, maybe fear a little. . .

PRELUDE

In Olden Times, When Wishing Still Helped

THIS IS NOT a fairy tale. Certainly it is not one that has been sanitized, homogenized, or Disneyfied, bloodless in every possible sense of the word, beasts and human monsters defanged and claws clipped, the children safe and the children saved, the hard truths harvested from hard lives if not lost then obscured, and purposefully so.

* * *

Last night there was confusion as to whether turning off the lights was a recommendation or if it was a requirement in accordance with the government-mandated curfew. After her husband, Paul, was asleep, Natalie relied on her cell phone’s flashlight in the bathroom as a guide instead of lighting a candle. She has been getting clumsier by the day and didn’t trust herself to casually carry fire through the house.

It’s quarter past 11 A.M., and yes, she is in the bathroom again. Before Paul left three hours ago, she joked she should set up a cot and an office in here. Its first-floor window overlooks the semi-private backyard and the sun-bleached, needs-a-coat-of-stain picket fence. The grass is dead, having months prior surrendered to the withering heat of yet another record-breaking summer.

The heat will be blamed for the outbreak. There will be scores of other villains, some heroes too. It will be years before the virus’s full phylogenetic tree is mapped, and even then, there will continue to be doubters, naysayers, and the most cynical political opportunists. The truth will go unheeded by some, as it invariably does.

To wit, Natalie can’t stop reading the fourteen-day-old Facebook post on her town’s “Stoughton Enthusiasts” page. There are currently 2,312 comments. Natalie has read them all.

The post: Wildlife Services is informing the public that rabies vaccine baits are being dropped in the MA area in coordination with the Department of Agriculture. Baits are also being dropped in targeted areas of surrounding states RI, CT, NH, VT, ME, NY, and as a precaution PA. The vaccine is in a blister pack, army-green. Baits will be dropped by airplane and helicopter until further notice. If you see or find a bait, please do not disturb it. Not harmful but not for human consumption.

The photo: The size of a dollar coin, the top of the bait pack is rectangular, has a puttylike appearance, and the middle leavened like a loaf of bread. It looks like a green, bite-size Almond Joy.

(Natalie and Paul have already stress-eaten most of the large variety bag of Halloween candy and it’s only October 21.)

The back of the bait pack has a warning label:

MNR 1—888-555-6655Rabies Vaccine DO NOT EAT Live adenovirus vector Vaccin antirabique NE PAS MANGER Vecteur vivant d’adénovirusMNR 1—888-555-6655

* * *

A small sample of the unedited comments to the Facebook post, in chronological order:

What if an animal eats like twenty of these?This sounds really dumb. There has to be a better way.

Vaccinating as many animals within a population is the only proven way to stop the spread. You can’t get ALL animals to voluntarily walk up to the vet for vaccinations. Seriously, the fact that we have effective baits to drop is huge and better than doing nothing.

What if a child eats it? This can’t be okay.

That’s why there’s the warning. And I doubt they’re dropping this stuff in the backyards. Only in the woods.

They say its some weird scary new strain.

A rabid animal is more dangerous than eating a vaccine.

Vaccines is what makes you sick. Everyone knows that.

I live in a wooded area and I have cats and grandkids. I don’t want them dropping that shit near me.

I ate four baits and now my erection is HUGE and GREEN and it won’t go away.

HULK SMASH!!!!

This isnt rabies. This is something knew.

I’m hearing you don’t even have to get bit to get it.

They don’t know.

Regular rabies is slow, usually takes weeks. They’re saying this thing moves through you in minutes.

42 confirmed human cases in Brockton. 29 in Stoughton. 19 in Ames.

Where are you hearing this?

What are the symptoms???

Headache and flu-like symptoms but it gets soooo much worse and you go crazy and you get weird and violent and you attack people and you’re fucked and everyone is fucked because there is no cure.

That’s not true. The original post is about the vaccine. Stop trying to scare people.

We’ve been quarantined. Nice knowing everybody.

Fuuuuuuuuuuuuuuck!

My sister said they’re closing Good Samaritan Hospital in Brockton. Overrun.

What do you mean by overrun?

I called my pediatrician’s office and there’s only a message saying go to Good Samaritan. What are we supposed to do???

I live near there and heard machine guns.

You know what a machine gun sounds like do ya?

they cant do anything for any one any way. time to hunker in the bunker until its over. people are going fast.

They don’t know what they’re doing. We’re so screwed.

We have to stay together and share information. Good information. No more wild rumors, and don’t use the word zombie, and just obviously false bullshit here please.

None of this is gonna work. We should kill all the animals, kill all the infected. Sounds cruel but if we can’t save them kill them before they get us all sick.

The bathroom window is latched shut. The white shade is pulled down, and Natalie keeps both eyes on it. Urine rushes out of her, and though she’s alone, she’s embarrassed by how loud it is without the masking drone of the bathroom fan.

AM radio crackles through the smart speaker on the kitchen counter as though the poor reception and sound quality are nothing but a special effect from a radio play, its time and hysteria getting a reboot.

One radio host reiterates that residents are to stay in their homes and keep the roads clear, only using them in the event of an emergency. She reads a brief list of shelter locales and hospitals within the Route 128 belt of metro Boston. They move on to reports of isolated power outages. No word from National Grid as to the cause or expected duration of service interruption. National Grid is already critically understaffed because the company is mired in a lockout of a significant number of its unionized field electricians and crews in an effort to eliminate employee pensions. Another newscaster speculates on the potential use of rolling brownouts for communities that are not cooperating with the quarantine and sundown curfew.

Paul went to Star Supermarket in Washington Plaza, which is only a little over a mile from their small, two-bedroom house. He is supposed to pick up a solar-and-hand-crank-powered radio with other supplies and food. The National Guard is overseeing the distribution of rations.

Rations. This is where they are fifteen days before their first child’s due date. Fucking rations.

It’s an overcast, gray autumn late morning. More out of superstition than fear (at least, that’s what she tells herself), Natalie has turned the lights out in the house. With the bay window curtains drawn, the first floor is a cold galaxy of glowing blue, green, and red lights, mapping the constellation of appliances and power-hungry devices and gadgetry.

Paul texted fifty-seven minutes ago that he was almost inside the store but his phone was at 6 percent battery so he was going to shut it off to save the remaining juice for an emergency or if he needed to ask for Natalie’s “suggestions” (the scare quotes are his) once inside the supermarket. He is stubbornly proud of his tech frugality, insisting on not spending a dime to upgrade his many-generations-ago, cracked-screen phone that has the battery-life equivalent of a mayfly’s ephemeral life-span. Natalie cursed him and his phone with “Fuck your fucking shitty phone. I mean, hurry back, sweetie pie.” Paul signed off with “The dude in front of me pissed himself and doesn’t care. I wanna be him when I grow up. Make sure you don’t come down here. I’ll be home soon. Love you.”

Natalie closes the toilet lid and doesn’t flush, afraid of making too much noise. She washes her hands, dries them, then texts, “Are you inside now?” Her screen is filled with a list of blue dialogue bubbles of the repeated, unanswered message.

The radio announcer reiterates that if you are bitten or fear you’ve come in close contact with contaminated fluid, you are to immediately go to the nearest hospital.

Natalie considers driving to the supermarket. Maybe the sight of a thirty-four-year-old pregnant woman walking to the front of the ration line and dropping f-bombs on everyone and everything would get Paul in front of Piss Pants, into the store, and home sooner. Like now. She wanted to go with him earlier, but she knew her back, legs, joints, and every other traitorous part of her body couldn’t take standing in line with him for what they had assumed would be an hour, maybe two.

She’s mad at herself now, thinking she could’ve alternated standing in line and sitting in the car. Then again, who knows how far away Paul had to park, as his little trip to the mobbed grocery store is going on three hours.

She texts again, “Are you inside now?”

Her baby is on the move. Natalie imagines the kid rolling over to a preferred side. The baby always seems to lash out with a foot or readjust its position after she uses the bathroom. The deeply interior sensation remains as bizarre, reassuring, and somehow heartbreaking as it was the day she felt her first punches and kicks. She rubs her belly and whispers, “Why doesn’t he text me on someone else’s phone? What good is saving his battery if we have an emergency here and I can’t call him? Go ahead, say, ‘You’re fucking right, Mommy.’ Okay, don’t say that. Not for a couple of years anyway.”

Natalie hasn’t left the house in four days, not since her employer Stonehill College broke rank with the majority of other local colleges and closed its dorms, academic, and administrative buildings to students and employees, sending everyone home. That afternoon camped out at the kitchen table, Natalie answered Development Office emails and made phone calls to alumni who were not living in New England. Only four of the twenty-seven people she spoke to made modest donations to the school. The ones who didn’t hang up on her wanted to know what was going on in Massachusetts.

Natalie is jittery enough to pace the first floor. Her feet are swollen even though the prior day’s unusual heat and humidity broke overnight. Everything on or inside (thanks but no thanks, hemorrhoids, she thinks) her body is swelling or already in a state of maximum swollen. She fills a cup with water and sits on a wooden kitchen chair, its seat and back padded with flattened pillows, which are affectations to actual comfort.

The radio hosts read straight from the Massachusetts bylaws regarding quarantine and isolation.

Natalie sighs and releases her brown hair from a ponytail. It’s still wet from her shower earlier that morning. She reties her ponytail, careful to keep it loose. She plugs in her phone although the battery is almost fully charged, and then she hikes up her blue shirt-dress and sends a hand under the wide waistband of her leggings to scratch her belly. She should probably take off the leggings and let her skin breathe, but that would involve the considerable undertaking of standing, walking, bending, removing. She can’t deal with all the –ings right now.

Natalie opens the diary app on her phone, named Voyager. In her head she says the name of the app in French (Voyageur); she says it that way to Paul when she wants to annoy him. She’s been using the app to keep a pregnancy journal. The app automatically syncs her notes, pictures, videos, and audio files to her Google Drive storage. During the first two trimesters, Natalie had been using the app every day and often more than once. She shared her posts with other first-time moms and caused an amused stir within that online community when instead of posting pictures of her weekly belly growth, she shared pictures of her feet accompanied by her own hilarious (at least she thought so) jokes about how quickly the twins were growing. Natalie slowed down using the app considerably in the third trimester and most of those entries devolved into a clinical listing of discomforts, the saga of the strange red pointillist dots appearing on the skin of her chest and face (including a regaling of her doctor’s shrug, and deadpan, “Probably nothing, but maybe Lupus.”), work grievances, and a litanylike reiterating of her fear that she’ll be pregnant forever. Over the last ten days, she has only mustered a few updates.

Natalie opts to record an audio entry, first marking it as private and not to be shared to those who follow her online: “Bonjour, Voyageur. C’est moi. Yeah. Fifteen days to go, give or take. What a terrible saying that is. Give or take. Say it fast and you can’t even understand it. Giveortake. Giveortake. I’m sitting alone in my dark house. Physical discomforts are legion, but not thinking about that so much because I’m utterly terrified. So I have that going for me. Wearing the same leggings for the fifth day in a row. I feel bad for them. They never asked for this. (Sigh) I should turn on a light. Or open the curtains. Let some gray in. Don’t know why I don’t. Fucking Paul. Turn on your goddamn—”

Her phone buzzes and a text from Paul bubbles onto the top of the screen. “Finally out. Bundles in the car. Be home in 5.”

She suppresses the urge to make fun of his actually typing the word “bundles.” Saying it is bad enough. She types, “Yay! Hurry. Be safe but hurry. Pleeeeze.”

She tells the smart speaker to turn down the volume until it’s inaudible. She wants to listen for Paul’s car. The empty house makes its empty-house sounds, the ones with frequencies attuned to imagination and worst-case scenarios. Natalie is careful to not make any of her own sounds. With her phone she checks online news and Twitter and none of it is good. She returns to Voyager and types a riff on her dad’s favorite saying: “A watched clock never boils.”

Paul’s car and its clearing-of-a-throat engine finally chugs up their sleepy street and rounds the bend of the fenced front yard. His green Forester is a twenty-year-old beater; 200,000 miles plus and standard transmission. Another endearing/annoying quirk of his, claiming he’ll only ever drive used standards as though it’s a quantifiable measure of his worth. More annoying, he’s not a gearhead and cannot fix cars himself, so invariably his jalopy is in the shop and then she is left having to build extra time in her schedule getting him to and from the train station.

As the green machine crunches its way down their sloped gravel driveway Natalie struggles into a standing position. She unplugs and then deposits her phone in a surprisingly deep pocket of her unzipped gray hooded sweatshirt. In her other pocket are her car keys, which she has kept on her person since leaving Stonehill.

Natalie walks into the living room, her footsteps in sync with Paul’s march on the gravel. She stops herself from calling out to him. He shouldn’t walk so loudly; he needs to be more careful and soft-footed. Arms loaded with bundles (Dammit, yes, fine, they are “bundles”), he emerges from behind the car. The Forester’s rear hatch remains open and the little hey-you-left-a-door-ajar dome light shines an obnoxious yellow inside the car. She considers yelling out to Paul again, telling him to shut the hatch.

Paul comically struggles to unlatch the fence’s thigh-high entry gate without putting down any of the grocery bags. Only, he’s not laughing.

Natalie is on the screened-in porch and whispers out one of the windows, “Can I get that for you?” She has an urge to laugh maniacally and an equally powerful urge to ugly-cry. She opens the screen door, proud that she dares stick her head outside and into the quarantined morning. She briefly imagines an impossible time of happiness and peace years from now, regaling their beautiful and mischievous child (she will insist her child be mischievous) with embellished adventure stories of how they survived this night and all the others to follow.

Natalie returns to herself and to a now of stillness and eerie quiet. Exposed and vulnerable, she’s overwhelmed by the tumult within her and Paul’s microworld and the comprehensive horrors of the wider world beyond their little home.

Paul mutters his way through swinging the creaking gate halfway open, where it gets jammed, stuck on the gravel (like always). He shuffles down the short cement walkway. Natalie stays inside the porch and holds open the door until he can prop it open for himself with a shoulder. Neither knows what to say to the other. They are afraid of saying something that will make them more afraid.

Paul waddles through the house into the kitchen and drops the bags on the table. Upon returning to the front room, he overexaggerates his heavy breathing.

Natalie steps into his path, grinning in the dark. “Way to go, Muscles.”

“I can’t see shit. Can’t we open the windows or turn on a light?”

“Radio said bright light could possibly attract infected animals or people.”

“I know, but they mean at night.”

“I’d rather play it safe.”

“I get it, but put it on just until I get all the groceries in.”

Natalie whips out her phone, turns on the flashlight app, and shines it in his face. “Your eyes will adjust.” She means it as a joke. It doesn’t sound like a joke.

“Thanks, yeah, that’s much better.”

He wipes his eyes and Natalie leans in for a gentle hug and a peck on the cheek. Natalie is only a disputed three-quarters of an inch shorter than Paul’s five-nine (though he inaccurately claims five-ten). Pre-pregnancy, they were within five pounds of each other’s weight, though those numbers are secrets they keep from each other.

Paul doesn’t return the hug with his arms but he presses his prickly cheek against hers.

She asks, “You okay?”

“Not really. It was nuts. The parking lot was full, cars parked on the islands and right up against the closed stores and restaurants. Most people are trying to help each other out, but not all. No one knows what they’re doing or what’s going on. When I was leaving the supermarket, on the other side of the parking lot, there was shouting, and someone shot somebody I think—I didn’t see it, but I heard the shots—and then there were a bunch of soldiers surrounding whoever it was on the ground. Then everyone was yelling, and people started grabbing and pushing, and there were more shots. Scariest thing I’ve ever seen. We’re so—it’s just not good. I think we’re in big trouble.”

Natalie’s face flushes, as his tremulous, muted voice is as horrifying as what he’s saying. Her pale skin turns red easily, a built-in Geiger counter measuring the gamut of emotions and/or (much to the pleasure and amusement of her friends) amount of alcohol consumed. Giving up drinking during the pregnancy isn’t as difficult as she anticipated it would be, but right now she could go for a glass—or a bottle—of white wine.

What he says next is an echo of a conversation from ten days ago: “We should’ve driven to your parents’ place as soon as it started getting bad. We should go now.”

That night Paul stormed into the bathroom without knocking. Natalie was standing in front of the mirror, rubbing lotion on the dry patches of her arms, and for some odd reason she couldn’t help but feel like he caught her doing something she shouldn’t have been doing. He said, “We should go. We really should go. Drive down to your parents’,” and he said it like a child dazed after waking from a nightmare.

That night, she said, “Paul.” She said his name and then she stopped, watched him fidget, and waited for him to calm himself down. When he was properly sheepish, she said, “We’re not driving to Florida. My doctor is here. I talked to her earlier today and she said things were going to be okay. We’re going to have the baby here.”

Now, she says, “Paul. We can’t.”

“Why not?”

“We’re under a federal quarantine. They won’t let us leave.”

“We need to try.”

“So are we going to, what, drive down 95 and into Rhode Island, just like that?” Natalie isn’t arguing with him. She really isn’t. She agrees they are indeed in big trouble and they can’t stay. She doesn’t want to stay and she doesn’t want to go to an emergency shelter or an overburdened ( they said overrun) hospital. She’s arguing with Paul in the hope one of them will stumble upon a solution.

“We can’t stay here, Natalie. We have to try something.”

He puts his hands inside hers. She squeezes.

She says, “What if they arrest us? We might get separated. You were just telling me how crazy it was at Star Market. Do you think it’s any better on the highways or at the state borders?”

“We’ll find some open back roads.”

Yes, back roads. Natalie nods, but says, “Maybe we’re at the worst point now—”

“I didn’t even tell you there was a fox staggering in the middle of the Washington Corner intersection like it was drunk—”

“—the quarantine will help get the spread of the illness under control—”

“—and it fucking dove right at my front tire.”

“—everyone will be all right as long as we don’t . . .”

Natalie continues talking even though there’s the unmistakable sound of footsteps on their gravel driveway. Her ears are attuned to it. She’s lived in the house long enough to know the difference between the sustained crunch and mash of car tires, the light, maracalike patter of squirrels and cats, the allegro rush of paws from the neighbor’s dog, a goofy Rhodesian ridgeback the size of a small horse (a shooting star of a thought: Where are her neighbors and Casey the dog? Did they leave before the quarantine?), and the percussive gait of a person.

The steps are hurried, quickly approaching the house, yet the rhythm is all wrong. The rhythm is broken. There’s a grinding lunge, a lurch, two heavy steps, then a hitching correction, and a stagger, and a drag. Someone or something crashes into the propped open gate and bellows out three loud barks.

After the initial shock, Natalie all but melts with relief, believing (or wanting to believe) what she hears is in fact Casey the dog. Shock turns to worry. She wonders why Casey would be out on her own. The guy on the radio said unvaccinated family pets could be insidious vectors of the suspected virus.

Natalie turns and she cranes her head and looks out the front door and through the porch. A large, upright blur passes by the small row of screened windows. The barks return and they are more like expectorating coughs, ones that sound painful. There is a man standing less than ten feet away from her. He opens the screen door, and says in a dry, scratchy, but clear baritone, “Fall came and it began to rain. Left out in the cold and rain.” Then he grunts, “Eh-eh-eh,” a vocalization that is all diaphragm and back of the throat.

Natalie and Paul yell at the man to go away. They shout questions and directions to each other.

The white man is large, over six feet tall and closer to three hundred pounds than he is to two hundred. He wears dirty jeans and a long-sleeve T-shirt advertising a local brewery. He steps through the door and fills their porch. With each coughing bark he bends and contorts, and then his body snaps back into an unnatural rigidity. He points and reaches toward Natalie and Paul. Natalie can only see the shape and contour of the man’s face as he’s silhouetted by the dim daylight behind him.

“Eh-eh-eh.”

Despite her all-consuming fear, there’s a nagging recognition of those primitive monosyllables buried in Natalie’s ancestral memory. Hearing him is enough to know, without the aid of visual cues and without the context of the ongoing outbreak, that the man is sick. He is terribly and irreparably ill.

Natalie’s fear morphs into a self-preservation shade of rage. Her fists clench and she steps forward and yells, “Get the fuck off our porch!”

Paul moves more nimbly and darts in front of Natalie. He swings the front door shut with enough force to rattle the frame and wall. His hand momentarily loses contact with the doorknob and he is not able to get the door locked before the man is already forcing it back open.

“Natalie?” Paul shouts her name as though it is a question, a question that is not rhetorical yet has no answer.

The door swings open, forcing Paul back into the house. The bottoms of his sneakers squeak as they slide over the wooden floor. Paul bends his legs, lowers a shoulder, attempting to gain purchase, to find the leverage he has lost forever. His feet stop sliding and they tangle, tripping him up. Paul falls onto his knees and the fiberglass door sweeps him away.

The man pushes the door fully open and presses Paul against the wall. He doesn’t stop pushing. The man almost fully eclipses the white door. He is the dark side of the moon.

The man shouts, “I only want to speak! Let me in! Not by!” He yanks the door back toward him and then he smashes it into Paul. The man and the door become a simple machine, then a high revving piston. The impacts of the door into her husband and her husband into the wall make thudding, sickening, hollow sounds. Paul’s screams are muffled. The walls and floors shake; the big bad wolf is blowing their little house down.

Natalie dashes the short distance into the kitchen. She knocks over a large blue cup half filled with the water she should’ve been drinking earlier, and she backhands the smart speaker out of her way while grabbing the chef’s knife from the cutting block.

The front door slams closed. The volume of the men’s shouting increases.

Natalie yells, “Go away!” and “Leave him alone!” and she runs back into the front room, knife held in front of her like a torch. Her eyes have adjusted to the dark of the house.

Paul is sitting on the floor and scrabbling to get his feet under him. Blood runs down his forehead and leaks from a wound near his right elbow. The man crouches over Paul, looms over him, an object of undeniable gravity. His great hands are clamped on Paul’s shoulders and pull him into a bear hug. Paul’s left arm is pinned to his side. With his free hand Paul punches and tries to push the man’s face away from his. The man shouts indecipherable, plosive-heavy gibberish, and stops abruptly as though suddenly empty of the mad new language, as though he’d correctly recited an arcane ritual, and he bites Paul repeatedly. The bites are not sustained and are not flesh rippers. They are quick like a snake’s strike. The man’s mouth doesn’t stay latched onto any one spot. In a matter of seconds he bites Paul’s arm and he bites Paul’s chest and he bites Paul’s neck and he bites Paul’s face.

“Let me in not by!”

The man’s shirt is torn and stained red above his left shoulder, near his neck. Tremors wrack his arms and body. He retches and shouts a moaning variant of no. He shakes his head and turns away, appearing to be doing so at the sight of the blood, as though it upsets him, or angers him, but he doesn’t stop biting.

Natalie charges across the room with the knife raised.

Paul gains his feet and both men stand and straighten. The man still has Paul’s torso constricted within his arms. Paul lashes out one last time with his right hand, connecting with the man’s eye. The man shrieks and barks and takes two steps forward, lifting and carrying Paul to the corner of the front room. The man drives his weight forward and down, mashing the back of Paul’s head and neck into the thick oak seat of Natalie’s mother’s antique rocking chair. Upon contact there’s a wet, pulpy pop and a sharp snap.

Natalie brings the knife down, aiming for the center of the man’s back, but he turns, knocking her arm off its trajectory. The knife drags across his left shoulder blade, carving a parabolic arc through his shirt and skin.

The man pivots and is face-to-face with Natalie. He’s middle-aged, balding, familiar in an everyman, nondescript way. He might be from the neighborhood and he might not. His face is contorted into dumb, inchoate rage and fear. His mouth is ringed in foamy saliva and blood. He shouts and Natalie can’t hear what he is saying because she is shouting too.

She re-raises the knife and jabs at his thick neck. The man blocks the knife with his hands, clumsily pawing at the blade, earning deep slices on his palms and the pads of his fingers. He cries out but doesn’t retreat. He grabs her wrist. His hands are hot and blood-slicked, and he pulls her into him, against him. She can feel the appalling heat of his fever through the tights covering her belly.

The man coughs in her face and his breath is radioactive. His cracked lips quiver and spasm, strobing out flashes of smiles and snarls. His tongue is an agitated eel darting between the oval of thick, viscous froth.

He is all mouth. His mouth opens.

Natalie leans away and simultaneously she knees his groin but without her weight under her, there’s no leverage and there isn’t much force behind the blow.

The man pulls her right arm above her head. He quickly latches his mouth to the underside of her forearm and he bites. Her thin sweatshirt offers no protection. She screams and drops the knife. She wants to shake and yank her arm away but she is also instinctually afraid to move and leave a chunk of herself behind. The crushing pressure combined with a sharp stinging burn at the broken skin, a pain unlike anything she’s felt before, runs up her arm even after he lets her go and she stumbles backward and falls into a sitting position on the couch.

The man opens and closes his bleeding hands and he briefly but loudly sobs as though in recognition of what’s broken in him and what he has broken. Then that bark. That fucking bark.

The man pivots and returns his attentions to Paul, who hasn’t moved, who isn’t moving. Paul is splayed on his back. His head is between the wide runners of the rocking chair and rotated toward the wall. The amount of rotation isn’t natural, isn’t possible. There’s a bulge in his neck, the skin taut over a knotty protrusion, a catastrophic physiological and topographical error.

Natalie clambers off the couch, and despite the wildfire pain in her arm and the warning stitch in her lower left side she bends to the floor and picks up the knife. Her bite wound throbs, the pain expanding, radiating with each pulse.

The man lifts Paul and resumes biting and thrashing him about as though rushing through a menial task that must be completed. He bounces Paul’s body off the door, the wall, and the rocking chair.

Paul issues no cries of pain. There is no voluntary motion.

Natalie sees a horrifying glimpse of the back of Paul’s caved-in, deflated skull. The boneless slack with which his head lolls and dangles demonstrates beyond doubt that his neck doesn’t work anymore, will never work again.

Natalie brings the knife down with both hands and half-buries the blade between the man’s shoulder blades. She lets go and the knife stays buried.

The man groans and drops Paul between the rocking chair and wall. Some part of Paul’s body gongs off the metal panel of the baseboard heater.

Natalie shuffles backward to the open front door. Her left hand digs in the sweatshirt pocket for her car keys. They are still there.

The man spins around unsteadily, reaching behind his back for the out-of-reach knife. He is a wobbling top nearing the end of his rotations. He is out of breath and the man’s eh-eh-ehs are weakening huffs and puffs. His revolutions morph into a slow orbital path away from Natalie and the front door. He plods into the kitchen leaving a trail of red handprints on the wall to his right. His heavy, ponderous steps clapping on the hardwood floor become a shuffle and slide, as though his feet have transformed into sandpaper.

Natalie imagines nestling next to Paul’s body in the corner of the room while he is still warm, and then closing her eyes and wishing, praying, willing the house to collapse upon them so that she never has to open her eyes again.

Natalie doesn’t stay with her dead husband. Instead, she steps onto the porch on shaking legs. She holds her wounded arm away from her belly. She stifles the urge to cry out to Paul, to tell him sorry and goodbye. A cool breeze chills the sweat on her face.

As the sputtering big bad wolf disappears somewhere deeper into their little house, Natalie quietly shuts the front door behind her.

* * *

This is not a fairy tale. This is a song.

I

THEY BOTH WENT DOWN

RAMS

Dr. Ramola Sherman has been a pediatrician at Norwood Pediatrics for three years. Of the five physicians on staff, Ramola earns the most new-patient requests. Locally, her reputation has gotten out: Dr. Sherman is thorough, energetic, kind, and imperturbable while exuding the reassuring confidence of medical authority all parents, particularly new ones, crave. The children are fascinated by her English accent, which she is not above exaggerating to pluck a smile from a sick or pained face. She allows her youngest patients to touch the red streak running the length of her long, jet-black hair if they ask properly.

Ramola was born in South Shields, a large port town on the northeast coast of England where the River Tyne meets the chilly North Sea. Her mother, Ananya, emigrated from Bombay (now Mumbai) with her parents to England in 1965, when she was six years old. Ananya teaches engineering courses at South Tyneside and is a polyglot. She mistrusts most people, but if you manage to earn her trust, her loyalty knows no bounds. She doesn’t waste words and hasn’t lost an argument in decades. She is shorter than her daughter’s five-two but in the eyes of Ramola, her mother projects a much larger figure. Ramola’s father, Mark, is a white man, nebbish-looking with his wire-rimmed glasses, face often shielded with one of his three daily newspapers, yet he is an intimidating physical presence with thick arms and broad shoulders befitting his lifelong career in masonry. Generally soft-spoken, he is equally quick with a joke as well as a placation. Hopelessly parochial, he has left the UK only five times in his life, including three trips to the United States: once for Ramola’s graduation from Brown University, a second time five years later when she graduated from Brown’s medical school, and a third time this most recent summer to spend a week with Ramola. The unrelenting humidity of greater Boston in July left him grumbling about how mad the climate was, as though the good citizens of New England had chosen the temperature and dew point. Ananya and Mark’s infamous and quite possibly apocryphal first date featured a distracted viewing of Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a trip to a notorious pub, and the first match in what would become a playful if only occasionally contentious decades-spanning pool competition between the two. Both parents steadfastly claim to have won that first match.

It’s late morning. Ramola finishes eating cold, leftover white pizza that has been in the fridge for four days, before video chatting on Skype with her mother. Ananya’s image jumps all over Ramola’s laptop screen, as Mum can’t help but gesticulate with her hands, including the one holding her phone. Mum is concerned, obviously, but thankfully calm, and listens more than she talks. Ramola tells her the morning has been relatively quiet. She hasn’t left her townhouse in two days. She’s done nothing but sit on the couch, watch news, drink hot chocolate, and check emails and texts for updates regarding her role in the emergency-response plan. Tomorrow morning at six A.M., the second tertiary medical personnel from Metro South are to report to Norwood Hospital. Thirty-six hours ago all first tertiary were called in and assigned by Emergency Command Center unit managers. Now they already need the second wave of emergency help. Her being called in relatively soon after the first tertiary is not a good sign.

Ananya places a free hand above her heart and shakes her head. Ramola is afraid tears might be coming from one or both of them.

Ramola says she should go and read through the training protocols (she has already done so, twice) and so she can pack. She’ll be working sixteen-hour shifts for the foreseeable future, and likely sleeping at the hospital. It’s an excuse; her overnight bag is already packed and on the floor next to the front door.

Mum clucks her tongue and whispers a one-line prayer. She makes Ramola promise to be safe and to send updates whenever she can. Mum turns the phone away from her and points it at Mark. He’s been there the whole time, off-screen and listening, sitting at their little breakfast nook, his elbows on the table, his meaty mitts covering his mouth, glasses perched on top of his head. His eyes always look so small when he isn’t wearing his glasses. He’s already been crying and Ramola tears up at the sight. Before she closes out the chat window, Dad waves, clears his throat, and in a voice coming from thousands of miles away, he says, “A right mess, innit?”

“The rightest.”

“Be safe, love.”

Ramola is thirty-four years old and lives by herself in a two-bedroom, 1,500-square-foot townhouse, one of four row units in a small complex called River Bend in Canton, Massachusetts, which is fifteen miles southwest of Boston. Her well-meaning parents encouraged her to buy the townhouse, telling her she was a well-paid professional and “of an age” (Ramola’s “Thanks for that