Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honford Star

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Kim Tongin (1900-1951) is one of Korea's earliest and most respected modern writers whose naturalist fiction brilliantly depicts Korean life during a period of profound social change. Namesake of the prestigious Dong-in Literary Award, Kim Tongin's succinct writing style can still inspire readers and provide insight into early 20th century Korea over 60 years after his death. Finally, a volume of Kim Tongin's short stories, most of them previously untranslated, is available to readers of English.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 424

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Born to a wealthy family in P’yŏngyang, kim tongin (1900-1951) is one of Korea’s earliest and most respected modern writers whose naturalist fiction brilliantly depicts Korean life during a period of profound social change. Namesake of the prestigious Dong-in Literary Award, Kim Tongin’s succinct writing style, complex psychological portraits, and detached point of view provide insight into early 20th century Korea.

grace jung is a writer, translator, and filmmaker from New York. She is the author of Deli Ideology and producer of the feature documentary A-Town Boyz. She is currently a PhD candidate in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Los Angeles, California. She is a former Fulbright scholar.

youngmin kwon is a professor of Korean literature at Seoul National University and former dean of the College of Humanities. He is currently a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He has written and edited numerous volumes of literary history, literary criticism, and reference works on modern Korean literature, and is the current president of the International Association of Comparative Korean Studies.

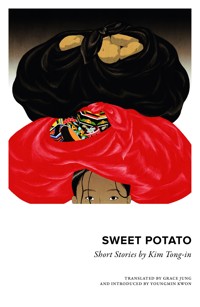

SWEET POTATO

collected short storiesby kim tongin

Translated bygrace jungIntroduced by youngmin kwon

This translation first published by Honford Star 2017honfordstar.comTranslation copyright © Grace Jung 2017Introduction copyright © Youngmin Kwon 2017All rights reservedThe moral right of the translator and editors has been assertedISBN (paperback): 978-1-9997912-0-9ISBN (ebook): 978-1-9997912-1-6A catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryCover illustration by Jee-ook ChoiBook cover and interior design by Jon GomezPrinted and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YYThis book is published with the support of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea).

www.honfordstar.com

Contents

INTRODUCTION

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

SWEET POTATO

THE LIFE IN ONE’S HANDS

BOAT SONG

FLOGGING

BARELY OPENED ITS EYES

SWEET POTATO

FIRE SONATA

LIKE FATHER LIKE SON

RED MOUNTAIN

A LETTER AND A PHOTOGRAPH

NOTES ON DARKNESS AND LOSS

THE MAD PAINTER

THE OLD TAET’ANGJI LADY

MOTHER BEAR

THE TRAITOR

A NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATION

INTRODUCTION

Style and Technique inKim Tongin’s Fiction

1

Kim Tongin was born on 2 October 1900 in P’yŏngyang,South P’yŏngan Province, in the north-western area of the Korean peninsula. His father, Kim Taeyun, a local magnate in P’yŏngyang, recognized the importance of Enlightenment thought, became a Christian and eventually a Protestant elder. After finishing elementary school in P’yŏngyang, Tongin moved to Japan at the urging of his father. There he graduated from Meiji Gakuin University’s Middle School and later took courses at the Kawabata Art School.

In 1919, Tongin started the first literary magazine in the Korean language. Creation (Ch’angjo) was published in Tokyo, and included works contributed by Chu Yohan, Chŏn Yŏngt’aek and Ch’oe Sŭngman. In the magazine, Tongin emphasized literature as an autonomous art form and championed ‘art for art’s sake’. Creation was an important medium for popularizing modern writing styles among Korean intellectuals in the early part of the twentieth century.

Tongin’s short story ‘The Sorrows of the Weak’ (yakhanchaŭi sŭlp’ŭm, 1919) featured in Creation’s inaugural issue, establishing him as a serious writer and he forthwith poured his energies into writing fiction in the Korean language. Other stories of his such as ‘Boat Song’ (paettaragi, 1921) were early templates for Korean writers interested in modern literary techniques.

After the successful publication of Creation’s first issue, Kim left school and returned to Korea. In March 1919, the Japanese colonial police discovered from Tongin’s younger brother, Tongp’yŏng, that Tongin had penned a memorandum for the anti-colonial March First Movement, and they jailed Tongin for four months on charges of violating publication law. Tongin recounted his prison experiences in his short story ‘Flogging’ (t’aehyŏng, 1922–1923).

When Creation was discontinued in 1921, Tongin started a second literary magazine called Spirit Altar (yŏngdae),which was contributed to by the writers from Creation magazine along with new talents such as Kim Yŏje and Kim Sowŏl. In 1923, he published a collection of original short stories under the title of his 1921 story, ‘The Life in One’s Hands’(moksum, literal translation ‘Life’).

Tongin then published a series of works expounding a Zola-esque, naturalistic view of life, including ‘Sweet Potato’ (kamja, 1925). Following this, he published works such as ‘Fire Sonata’ (kwangyŏm sonat’a, 1929) and ‘The Mad Painter’ (kwanghwasa, 1935) in a sharply aestheticist vein employing the themes of artistic madness and aestheticist desire.

In the 1930s, Tongin tried his hand at long historical novels published serially in newspapers. These colourful historical novels flesh out the individual character and inner psyche of historical personages poised at the centre of well-known historical events, presenting new interpretations of their human side. This approach was a major break from the experimentality of Tongin’s earlier short stories.

In the final years of the Japanese colonial rule, Tongin could not but conform to the ruling policies of the Japanese imperialists. He visited war areas in the Manchurian region at the behest of the Chosŏn Governor General of Japan, and published articles in line with Japanese colonial directives. As Korean writers were divided into left and right political camps, Tongin chose to criticize the political partisanship of the leftists and organized the Association of Pan-Korean Writers in 1946, a right-wing nationalist group of Korean writers. In addition, he published short stories such as ‘The Traitor’ (panyŏkcha, 1946), critically depicting the pro-Japanese activities of literary figures at the end of Japanese colonial rule. He died on 5 January 1951, during the Korean War, at his home in Seoul.

2

No clear-cut determinations have been made as to why Tongin chose to become a literary artist. But something of his philosophy can be gleaned from his first work of literary theory, ‘On the Korean Conception of the Novel’ (sosŏre taehan josŏn sarame sasangŭl) in the journal Light of Learning (hakchikwang) No. 18, 1919. His worldview defines the novel as ‘a world expressing the human spirit’ and the literary world as ‘an expression of the individual’s inner consciousness’. His definitions are comprehensive and general but reveal Tongin’s attitude to literature, an attitude placing the highest value on the personal nature of literature and art. Tongin’s perception of literature as foremost a medium for individual expression essentially reduces art to the expression of individual emotions and desires.

Tongin’s literary philosophy was further expounded in his essay ‘The world of his own creation: comparing Tolstoy and Dostoevsky’ (chagiŭi ch’angjohan segye: t’olsŭt’oiwa tosŭt’oyep’ŭsŭk’irŭl pigyohayŏ) (Creation, No. 7, July 1920). This early editorial encapsulates his judgment on the fictitious nature of the novel and elucidates his awareness of the essence of art.

What is art? [...] the legitimate answer is ‘the world man creates by breathing life into his shadow’ – that is, the world that man himself controls. This reveals why art came into being and by what need. Man is not satisfied with the world God created. The world that pleases Man is created by the great creativity of his life, the world that comes into being only after it has been built up by his own energies and powers, even though it be an imperfect world […] The art produced from his great need is a shadow of life, a unique bible of life, the vitality of a love on which human life depends.

Tongin held up literature and art as the work of man’s towering creative mind, emphasizing the connection between artistic creation and the artist’s individual talent. Art, in so far as it relates to life, can only be achieved by the inner demands of the self. The truth to be embodied through art – namely, beauty – is closely linked to actual human life, and personal desires and creative intuition constitutes the principle of all artistic choice. Tongin viewed art as life created by an artist, not real life. The artist must dominate his art as a world of his own creation, and it is this mastery that determines the author’s greatness. For Tongin, art is a new creation of perfect life, wholly self-sufficient because its meaning exists independently of actuality.

This attitude is reflected in his fiction. Creating a truthful life is the fundamental task of fiction. For Tongin, the problem of life is the essence of existence and it is in fiction that life can achieve completed meaning. The aim of literature is to create a life that the artist can manipulate like a marionette. In most of Tongin’s short stories, the plots and characters occupy a fictional space quite unlike the realities of life in Tongin’s day. He affirms only pure artistic values and rejects all others, finding a space within the novelistic world where literature can exist in complete autonomy. This space is fictional, created by the artist outside the realm of real life. The problems of life that Tongin depicts in his fiction correspond to essential aspects of human existence largely independent of historical and social reality. Tongin was in pursuit of an artistic value that is both timeless and constant through these essential aspects of the human being. Of course, that artistic value derives from the completeness of the work’s internal structure. From the outset of his career as a writer, Tongin was obsessed with the form of the short story in serving a kind of functionality with regard to life and the possibility of its completed meaning.

3

Tongin’s early short stories ‘Boat Song’ and ‘Sweet Potato’ are fine examples of his narrative focus and style. The two works limit their focus to one aspect of life in order to show the contrasting destinies of the main characters. The characters’ personalities are created through the narrative technique.

‘Boat Song’ has a ‘story within a story’ narrative structure. This structure has the formal advantage of securing completeness of the inner story by dint of an outer story that enhances the credibility of the inner story. ‘Boat Song’ recounts the destruction of the relationship between two brothers following a misunderstanding by the hero who is trapped in his own feelings of inferiority. The older brother’s uncontrollable feeling of inferiority leads to the breakdown of the relationship between 1) himself, a man of gentle but honest character, 2) his sociable, pretty wife, and 3) his reliable, warm-hearted younger brother. Ultimately, the work shows that human destiny is defined by the ‘demands’ residing within each man. The tragic destiny playing out in the inner structure becomes intertwined with the experience of the narrator, ‘I’, existing in the outer frame. ‘Boat Song’ is less about describing the tragedy of a human life as inducing people to rethink the problem of life through the machinations of an inescapable tragic destiny.

The case of ‘Sweet Potato’ is different. This work follows the tragic fall of the heroine, Pongnyŏ, ending in the loss of her moral will amidst a life of extreme privation. At the root of the heroine’s dramatic downfall (that is, her death) is the external social factor of poverty. Prior to her fall, Pongnyŏ enjoyed a normative home education and was possessed of an intact ethical sense. But when her family falls into penury she is sold for 80 wŏn and weds a man twenty years her senior. Her husband’s laziness results in her becoming a slum dweller outside the Ch’ilsŏng Gate. Condemned to slum life, she goes and finds a job as a ‘worker who doesn’t work but is amply paid’ by selling her body to the supervisor. When she is caught stealing sweet potatoes from Mister Wang, she escapes certain doom by offering him her body, and maintains a relationship with him while taking money for her favours. Notable in this process is the way Pongnyŏ’s character rapidly devolves and the devolution’s fatalistic meaning. Also of importance is how external conditions of poverty can corrupt a human being. Unlike ‘Boat Song’, ‘Sweet Potato’ does not contain subjective commentary, and the work’s concise style reinforces the impression of objectivity. This contrast in attitude between ‘Boat Song’ and ‘Sweet Potato’ points to modern narrative techniques emphasizing balance between objective and subjective description in an array of fictional works.

Other short stories by Kim Tongin such as ‘Flogging’ and ‘Red Mountain’ foreground the contradiction and pain of Japanese colonial rule. Based on his own experience of imprisonment in a detention centre for violating the publishing law immediately after the March First Independence Movement in 1919, ‘Flogging’ is a detailed depiction of major and minor events taking place in a cramped prison cell. The work suggests that the circumstances of Japan’s oppressive reign over colonial period Koreans can be understood by reference to the scenes in the cell, but rather than expressing resistance to Japan, the story focuses on the ugly, egoistic instinct of those anxious to find comfort against their painful reality. ‘Red Mountain’ relates the pain, sorrow and patriotism of Koreans who, unable to survive the severe plunder of the Japanese Colonial period, went to live in Manchuria.

Tongin’s ‘Fire Sonata’ and ‘The Mad Painter’ are unconventional works written from unusual perspectives of the fierce desire to create art, and madness in the obsessed artist. The two stories are representative examples of Tongin ‘s aestheticist literature. ‘Fire Sonata’ expresses the author’s extreme advocacy of aestheticism. Aestheticism is the core philosophy of the artist in the story, a musician named Paek Sŏng-su who commits murder, arson and other crimes to transgress social taboos and thereby draw inspiration as a composer. Utilizing the ‘story within a story’ technique, the work appropriately adjusts narrative distance to achieve the compositional completeness that Tongin admired. ‘The Mad Painter’ also takes the form of a ‘story within a story’. The hero, Solgŏ, attempts to depict supreme beauty, the beauty of a beautiful woman’s face, with his brush. But supreme beauty does not exist in the real world, so he chases after fantasy instead, perpetrating acts of near insanity for the goal of enhancing his artistic achievement. Tongin pursues the tragedy of the artist because he is unable to achieve absolute beauty. The pursuit and inevitable frustration of failing to grasp through art the pure, transcendent beauty of life is at once the dream pursued by the painter within the story’s frame and the novelistic aesthetic of Tongin. Tongin’s obsession with the lives of artists striving to overcome the tragedy of their life derives from his own extreme distrust of reality.

The immensely popular historical novels published by Tongin in the 1930s reflect his escape from problems of colonial day-to-day reality and his conscious return to the historical past. His historical novels consist of historical material reworked using fictional narrative principles. The combination of historical fact and fictional elements opened up the possibility of employing aesthetics to view historical problems with an eye to contemporary reality.

4

Kim Tongin’s literary achievements had important literary historical significance, leading to the establishment of modern Korean fiction and its rapid popularization. From Yi Injik to Yi Kwang-su, Korean fiction before Tongin had been based on the full-length novel and was characterized by a broad historical pursuit of life as a whole and exploration of life’s meaning. However, Tongin was interested in the short story, where narrative could attain dramatic completeness by isolating and presenting a single section of human life for analysis.

Through the establishment and diffusion of the short story, Tongin made possible the advancement of modern novelistic techniques in Korean literature. One advance was the method of personifying characters in stories. Although not the case in all short stories, limiting the central characters to one or two people is a common feature of the form. This is shown in Tongin’s ‘Boat Song’, where the main character is described as a man who drifts around singing the ‘paettaragi’ tune. Since the number of important characters in the story are limited to one or two, the story’s attention can be focused on the protagonist. The character’s personality can be portrayed by drawing out particular aspects of the character’s life.

In Korean classical fiction, the narrative point of view was not clearly defined. Narrative distance was not maintained, as the narrator narrated everything with absolute authority. The lack of distance between subject and object means that maintaining narrative tension is made difficult, and suggests that people living in the era of classical novels did not have objective and rational perceptions and views. The rational subject was not properly established until the ‘New Novel’ (sinsosŏl) movement at the end of the nineteenth century, but vestiges from the classical period continued right up until Yi Kwang-su’s novel Mujŏng (1917). The narrator was given an omniscient role that completely dominated the narrative’s internal space.

However, Tongin’s narrative method included use of the past tense verb ending as an aspect of his literary style, and generalizing the third person pronoun kŭ (he) in the narrative. These developments helped the introduction of a narrative point of view that understands the aesthetic potential. A change of the narrator’s position in the story now meant that a clear line had been drawn with the world qua object, and the narrator has learned to place themselves at a distance from it. The ‘narrator’ gained the ability to view the outside world from a certain angle, define their own categories and establish their own status as a subject. Angle and distance for seeing the object became clear in Korean literature, as had the focus of description.

Thanks to stories such as ‘Boat Song’, ‘Red Mountain’ and ‘The Mad Painter’, the first-person narrator would become a standard literary technique in Korean fiction. Tongin incorporated the narrative past tense to maintain a strict distance between the narrative subject and object. He used the past tense ending to secure narrative distance, thereby enabling objective descriptions of objects through literary style. It is no exaggeration to say that the Korean literary establishment’s use of the narrative past tense in the novel originated with Tongin.

Kwon, YoungminEmeritus Professor of Seoul National UniversityAdjunct Professor of Korean Literature at UC Berkeley

TRANSLATOR’S NOTE

The Melodramatic, Meta and Impaired Stories of Kim Tongin

I noticed several patterns while translating this collection of Kim Tongin’s short stories: the first is the author’s gift at weaving melodrama; the second is his habit of meta-storytelling; the third is his obsession with the physically or mentally challenged. These three things pave a way into the author’s inner world as well as the significance of the period in which modern Korean literature began to take shape.

Scholars generally point to Kim’s realist/naturalist tendencies, and while this may be, what I discern the most is his love for melodrama. Quite a few of his stories include the trope of the fastidious young woman who tries and tries but can never make it out of poverty due to social constraints. A character such as this is a staple of classic melodrama, and although scholars generally pit Kim against Yi Kwang-su and his didactic literary tendencies, an argument can be made for Kim’s own knack for didacticism via melodrama – a form of storytelling that gives readers a clear sense of who is morally upright and who is not. Recurrent techniques of melodrama visible in Kim’s stories are certainly apparent in films and serialized dramas produced in contemporary Korea, particularly emotional excess such as tearfulness.1 Many of Kim’s characters suffer from a helplessness due to their p’al-ja – the circumstances they were born into but cannot change – and this often lends to moments of rage, madness or crying. Stories like ‘Sweet Potato’ shift more towards the ‘fallen woman’ category; in fact, a number of Kim’s stories fall under this genre. The misogynistic trope of punishing the woman who isn’t ‘virtuous’ is apparent in Kim’s work; female characters who don’t retain their virginity wind up dead or lost, whereas those who keep it are shrouded by an untouchable other-worldliness, giving us a glimpse into Kim’s patriarchal preoccupation with female chastity.2

In 1915, after transferring out of the Tokyo Institute, Kim became a student at the Meiji Institute in Japan where he developed not only an interest in literature but also film; thirteen years later, he and his brother tried to establish a film production company in occupied Korea but failed – a fate that other modernist writers have also succumbed to while chasing the romantic prospects of cinema (consider F. Scott Fitzgerald’s history with Hollywood).3 Reading Kim’s works, it is apparent why he would gravitate towards the visual medium. His stories read like screenplays; they contain the rhythm of a film with cutaways and close-ups to facial reactions, buildups to an explosive climax, a frightening horror that either looms or bares its face, intense emotionality and heavy sorrow. It’s no wonder that so many of Kim’s stories were adapted into films in the 1950s through the 1980s, including but not limited to ‘Sweet Potato’, ‘Fire Sonata’, ‘Like Father Like Son’ and ‘The Mad Painter’. ‘Sweet Potato’ also influenced Bedevilled (2010), directed by Jang Cheol-soo and written by Choi Kwang-young.4 Kim’s skill with dramatization, however, does not discount his sense of humour. ‘The Life in One’s Hands’ has some comical moments, as does ‘Flogging’, which contains instances of tenderness, although both stories are generally of a dark disposition. This balancing act is a testament to Kim’s versatility, and as Youngmin Kwon notes in the introduction, his colourful writing.

As Kwon mentions, Kim often creates ‘a story within a story’. Beyond this, however, Kim is a highly self-reflexive writer. In ‘Notes on Darkness and Loss’, the author refers to himself by his own name and writes in the first person, making the story closer to a personal essay than a work of fiction. In the case with ‘The Mad Painter’, the protagonist waits around for a story to come to him as he lounges around in the mountains before bringing another character to life. Although the transference is spelled out for the reader, the general feeling isn’t too far from Virginia Woolf’s style in texts like To the Lighthouse and Mrs Dalloway where the reader gets carried from one character’s interior into another’s. In ‘Barely Opened Its Eyes’, Kim demonstrates meta-storytelling by outright telling the reader that he is tired of writing this piece and would like to move on to another. In ‘Fire Sonata’, Kim preps the reader with a setting, and the rest of the story reads very much like a chamber play. In ‘The Mad Painter’, the narrator deliberates openly as to how he should end the story, a bit like a choose-your-own-adventure piece. In ‘The Old Taet’angji Lady’, Kim starts out by wondering aloud if his stories don’t sound hackneyed at this point in his career. These examples of bold self-reflexivity make Kim all the more interesting as not just a writer but as a character himself, unafraid to immerse his readers while also dialoguing with them directly while hovering above the story-world.

Returning to p’al-ja, I earlier noted Kim’s fixation on the physically or mentally challenged. In the cases with ‘The Old Taet’angji Lady’, ‘The Mad Painter’, ‘A Photograph and a Letter’ and ‘Mother Bear’, Kim delights in creating characters who are social rejects due to their physical appearance. In ‘Fire Sonata’ and ‘The Mad Painter’, characters suffer from impairments such as mental disturbances and blindness. In ‘Notes on Darkness and Loss’, ‘The Life in One’s Hands’ and ‘Like Father Like Son’, characters are invalids. In ‘Barely Opened Its Eyes’, there is a character with a deformed ear. Kyeong-hee Choi observes that many modernists during the colonial era had an ‘interest in bodily anomaly’ due to the colonial government’s censorship – a form of literary impairment. Choi argues that the authors of this period transgressed colonial censorship through their own form of ‘self-censorship’ in the form of impaired literary bodies by ‘amputating actions of the external censor’.5 Although Kim is often championed as an ‘art-for-art’s sake’ writer, his works demonstrate a clear political interest through literary transgressions with the bodily impaired, complicating his oeuvre’s ‘pure art’ status that scholars often cite. Kim was political, and in stories like ‘Flogging’, ‘The Traitor’ and ‘Red Mountain’, his activism shines through.

Kim produced stories that generate a vivid visual world through melodrama, suspense and humour, while maintaining a vision for modern Korean literature during the occupation through political rigour both as a writer and activist. This collection exhibits just some of the rich layers that this author possessed.

*

Because Kim was a writer from P’yŏngyang, many of the stories are set in places that remain largely inaccessible to the world. The beauty that Kim paints of North Korea produces a deep longing for these settings, while current events remind us of the national divide. Kim’s works contain many idiosyncratic words and expressions that are native to the P’yŏngan dialect or simply no longer in mode. Certain words and expressions, although Korean, are not necessarily native to everyone who is familiar with the language; dialects in Korean are diverse and can be drastically different from one another. Working around this, in addition to outdated terms and Japanese expressions, was challenging, but I had a good community of people to rely on with questions as they came and general support as I needed. For this, I’d like to thank Bruce Fulton, Ju-Chan Fulton, Dr Young Ae Choi, Todd Kushigemachi, John Jung, Tam Quach and Miru Kim.

Grace JungTranslator

1 For more on melodrama, see John G. Cawelti, ‘The Evolution of Social Melodrama’ Imitations of Life: A Reader on Film and Television Melodrama, (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 33-49.

2 What’s interesting (and troubling) is just how frequently this trope is used in popular works of contemporary literature and cinema by male writers and filmmakers (see essay by Gina Yu, ‘Images of Women in Korean Movies’, Korean Cinema: From Origins to Renaissance, (Seoul: CommBooks, 2007), 261-268). The trope of the female body as a symbol for masculinist-nationalist anxieties continue in these spheres, and the only way to move past this and discover new horizons is by creating more opportunities of media expression for women who have different ideas and understandings of the female body and its potentials.

3 Hyunsue Kim, Naturalistic Sensibility and Modern Korean Literature: Kim Tongin, (Florida State University, PhD diss., 2008), vi.

4 See Michelle Cho, ‘Beyond Vengeance: Landscapes of Violence in Jang Chul-soo’s Bedevilled’, (Acta Koreana, 17:1, 2014), 137-162.

5 Kyeong-Hee Choi, ‘Impaired Body as Colonial Trope: Kang Kyŏng’ae’s Underground Village’, (Public Culture, 13:3), 431-458; Choi references Kim’s ‘The Mad Painter’ in her footnote (432n).

SWEET POTATO

Collected Short Stories by Kim Tongin

THE LIFE IN ONE’S HANDS

I thought he was dead. He’d contracted a strange illness five months ago. At first, his appetite disappeared and he couldn’t eat. Then his belly gradually bloated. In fact, his entire body swelled. It looked like three or four bowls of water could pour out of his jaundiced face if someone pricked it with a needle. He said that his belly was in about the same condition. When asked if he was in any pain, he said that he wasn’t. He only complained of dizziness and the occasional nausea. He went to S Hospital and began to take medication, but his condition only worsened. He eventually checked into S Hospital as a patient. I went to see him every day. He was always lounging on an easy chair, and when I arrived, he greeted me happily, asking for a cigarette. It’s a Christian hospital, so they ban cigarettes among patients; he could only smoke when I paid a visit. He and the nurse were on familiar terms, so when she witnessed this transaction, she’d just give a knowing grin and leave it at that. Given his active nature, sitting still within hospital confines appeared to be a struggle for him. Then I took a trip for a couple of days to prepare for a job out of town. When I returned after two or three days to say goodbye, his health had changed drastically and he refused any visitors. I heard that the chief of medical staff had delivered some bad news, telling him that he was dying. When I heard this, I just turned around and went home.

He’s dying. This fellow, whose voice was once so full of energy that the power overflowed and flew in all directions around him, is dying. A person’s life is … unpredictable.

I don’t know when our relationship began, but it runs deep. While I was researching as an entomologist, he was writing brilliant poetry that was printed in newspapers and magazines here and there. Despite this, he and I had something in common. While I, on the one hand, had the scientist’s determination to dig out every part of the earth in order to find a way to live in a world that relies on human strength, he, on the other hand, had the artist’s determination to leave behind his imprint in some shape or form. Our point of commonality was a desire for expression. Our relationship doesn’t have an official starting point, but as I mentioned, it runs deep. So the moment must’ve been when we first declared our dreams to each other, which became our point of commonality.

When I heard that they had given him a death sentence, I wanted to rationalize my sadness on behalf of society: It is losing a talented and promising young man. But the surprising truth is that I was sad on my own behalf for losing a friend to have frank conversations with (I never had a friend who understood me as well as M). The next day, I left behind my ailing friend and took my long-awaited trip to the vast plains of Kangwŏn Province to collect insects. I took a butterfly net and insecticide to the field and wandered for two months collecting beetles, butterflies, and caddisfly.1 I put my dying friend M out of my mind during this time.

When I returned, my desk had a pile of letters. Among them was a letter from M:

I’m dying. Even the chief can’t help me now. I hate everyone who goes on living. I can’t wait for what I’m going through to happen to everyone else. Even you. But before I die, even though I dictate this letter, I just had to write a note of farewell to you. Although I hate you for being one of the ‘living people’, I also love you as a friend and will never forget you – not till death. I believe you’ll forgive me for these conflicting feelings.

This was written in another’s handwriting on hospital stationery. I was struck with the kind of loneliness that hits a child after losing its beloved dog to a beating. I imagined what he must have looked like while writing this letter to me: M forces his swollen body to sit upright with one arm, but only makes it up halfway. He summons the ghostwriter and begins to dictate his letter. When the ghostwriter reaches the line ‘I hate everyone who goes on living’, the ghostwriter suggests not putting in such a sentence. M frowns and shouts in a raspy voice:

‘How dare you discount a dying man’s last words!’ The ghostwriter, shocked, continues to write. M plops his ailing body back down on the hospital bed and closes his eyes. He no longer thinks about death but becomes obsessed with all kinds of life’s concerns.

‘Why am I dying?! People – not just people but animals, plants even, fish, the stream, even the ocean – are alive. Why do I have to die? There goes the tram. Damn it! I’m pissed. Die – all you who live on this earth. Disappear. Let’s all just disappear together!’ He bolts straight up on his bed in anger. His jaundiced face flushes bright red.

Ah. M’s dead. Whether it was me thinking back on our friendship or pitying a fellow man, my eyes welled up with hot tears. Without a doubt, M was the kind of person who was twice as obsessed with life and hated death just as much. So why should it be strange for someone like M to scream with all his might for everything to disappear? I called S Hospital to enquire the whereabouts of M’s grave. I wanted to go more to restore my own conscience than to comfort M’s resting soul. I just had to pay a visit to his grave and offer him a drink, but I couldn’t get any information from the hospital. They said that a person named M did check into the hospital but that he was discharged upon recovery. I thought it might’ve been someone with the same name as him so I enquired once more, but the nurse replied that she was a new nurse currently on her probationary period so she wasn’t sure. I asked for the chief, but she said that he was away. The resident physician was on call, and Nurse S, who looked after M, was no longer working there. I turned and sat at the table, laughing.

‘Ha ha ha ha! M is alive! M practically died then came back to life! Does this mean that life overcomes death? Ha ha ha ha.’

So a month’s time passed. This was four days ago. All I did for that month was think about M’s hometown, which is in North P’yŏng’an Province. This was all I knew about his hometown, but it was on my mind. Then the servant came to me and said that someone who looked just like M paid a visit.

M isn’t dead! But would something like this happen? Who could have saved the patient that the doctor had dismissed? He’s alive! According to the nurse-in-training, if M was dead, his news would be in the papers, but she hasn’t seen anything. He’s alive. I took a moment to put the pieces together in my head. I brought my scattered thoughts back in order as I bolted for the door. When I reached the door, I couldn’t see M’s body but I could sense his presence nearby. As soon as I rushed outside, I grabbed hold of every person I ran into.

He’s back. He’s back. He isn’t dead. He regained his strength …

‘I didn’t die after all.’ It was M’s voice. I looked up and saw M. His face glowed with strength and its expression read, Whoever told you I was sick? He gave me a friendly smile while peering back at me.

‘Come. Let’s go inside.’ I put my arm over his shoulders and led us both into the living room.

‘What on earth happened?’ I asked. He looked back at me blankly. I couldn’t explain my question.

‘A dead person coming back to life, I mean …’

‘A person’s life ought to have a price tag of one chŏn and five li.’2

It was my turn to stare back blankly.

He explained, ‘You’ll understand if you read my thought journal. In any case, I’ve come back to life. I left the hospital a month ago, and during that time I took a pleasant trip for myself. And I’ve appeared before you with twice the strength and energy as before, have I not? Even so, the price of my recovery is one chŏn and five li …’ He handed over a unique-looking manuscript – a collection of scrap paper with poorly scripted handwriting. I was eager to know what he meant by ‘one chŏn, five li’, so I snatched the manuscript and began to read.

*

Me and Life: M’s Thought Journal

Thought Piece One

I was at my wits’ end. My family continued to nag me even though I didn’t feel particularly ill. But my stomach did ache and sent faint waves of nausea, so I hauled my body by force onto a rickshaw and headed for the hospital to check in, which appeared before me like a structure of hell on earth. Each time the black rickshaw tires ran over rocks, the awfully bumpy ride relieved the extreme pain in my stomach with a cramp that pushed vomit all the way up to my throat before going back down. The sky looked tiny as though I was staring at it through binoculars. Its light was yellow like pollen yet dark as ash. The yellow looked endless. At the same time, it looked like it was falling down from the top of my head. And there appeared a peculiar mustard yellow cloud picking up speed as though it was racing against the rickshaw, heading south. The bright yellow sun must’ve been right beside it, but no matter how much I stared, it hung darkly over me.

For a cloudy spring day, the weather was quite fair. But to my eyes, the day seemed darker than winter’s. The sun was gloomy, but the inside of my head felt duskier. Murky and heavy. My skin was desensitized and felt as though it was completely separate from my body, and resting heavily on top of me. My body, having lost its connection to my head, stretched out idly. The nausea continued without fail. I would have been better off if my nausea turned to vomit, but for reasons beyond me, it stayed as nausea. It lingered inside my body. When I spat, saliva filled up inside my mouth within mere seconds. When I spat again, it came right back. When I swallowed the nausea back inside to hold it under my chest, it went down into my stomach, circled around then raced to my head, making me lose all my senses. Then it aimed for my fingers, producing spasms.

‘Die,’ I cursed, then shut my eyes. After my eyes closed and my sensation to the outer world reduced, the horrid spasm and nausea turned into pain. I’m not sure why pain is preferable over spasm. I could breathe.

This is it! A person experiences pleasure once he closes his eyes. After contemplating this thought that didn’t even make sense to me, I took in a deep breath of dusty air. The rickshaw rang its bell lightly, jumping over the rough and rocky terrain, riding far away, perhaps all the way to India. I got on the rickshaw at eleven thirty in the morning, but hadn’t heard the noon shots fired yet. For me, though, it felt like I’d entered tomorrow’s eve. I wanted to know the time, but the space between my hand and pocket felt no different from several hundreds of li. I couldn’t stand it any longer, and I opened my eyes. The people who hopped to the side of the kerb at the sound of the rickshaw bell looked like goblins you see dancing in hell for the god of the underworld.

‘How fun,’ I muttered to myself. I’m not sure why but it felt as though all the creatures in the heavens had come down to tickle me. Convulsions spread throughout my body. Every pore released nauseous sweat. The anxiety was overwhelming to the point where if I had a knife, I would’ve jumped out of the rickshaw to stab and kill a dozen people.

I came down with this illness (so mysterious not even the doctors have any answers) two months ago. At first, I didn’t want to eat. My stomach was constantly bloated. I ate some bread that was supposedly full of nutrients but that eventually came right back out of my mouth. My stomach looked like it belonged to a pregnant woman, gradually swelling up within days. It looked like a polished red cherry, nice and ripe. It looked like, if someone pricked it with a needle, it would gather cherry juice like eyes gathering tears. But my face was completely drained of blood till it turned yellow and eventually blue, save for my bloodshot eyes. My head grew heavy. Eventually all the weight gathered up towards my head. Right now, my head and body are two separate entities. I occasionally wondered where I would dispose of my head. I lost my mind completely. I would indulge in moments of extreme happiness or upset myself with endless sorrow by mixing up the events of my daydreams with reality. I’d even befriended several important historical figures. Occasionally I would snap back to reality and the state of my illness. Goosebumps would cover me as if cold water was pouring down my head, and an inexplicably demonic fear would shatter my mind. The whoever-it-was doctor that diagnosed me would hand me some useless powder and water, calling it ‘medicine’.

Hospitalization. I ultimately came to this unavoidable conclusion. The bright yellow sky shook before me as though my binoculars were shaking. The road looked muddied with death below the sky – no, from up above in the sky – and a thirsty voice cried out from an unknown place. I couldn’t stand the nausea any longer, so I closed my eyes again. The rickshaw continued to run without stop. The sunlight pierced through my eyelids, turning orange, and travelled through my optic nerve towards the brain that stretched out my neck. It grabbed hold of my resisting brain and harassed it. I opened my eyes at the sound of the noon’s gunfire. Bang! The rickshaw man set down the bar. Before me was S Hospital’s hellish red light with two hands in its pocket, letting out a terrible laugh. By the power of absorption, I got sucked into the hospital. Slurp.

Thought Piece Two

This is practically hell. This terrible sadness. It is indescribable.

‘Uu-uu-uu …’ A single cry following a groan.

‘Ayu, ayu, ayu …’ A howling in the throes of death. The sound of the noisy tram disappears. When the whistle of the train goes off intermittently like an afterthought, it’s like hearing shrill screams of ghosts reverberating towards me from ten li in all directions – above, below, next door, all around. Ah, if this isn’t hell, I don’t know what is. If these aren’t the cries of invalids attacked by scorpions, what else could they be? Whether I’m scared or what, I can’t say. I’m nervous. The train takes off violently. I can feel its tremors.

That’s right. I’m taking off. Fiercely heading towards death. Off you go. Run with all your might. If you run into the devil, smack him. The devil is a blue light. With your red light erase his blue light. That’ll turn into a purple light. It becomes a purple firework.

‘Ai, save me …’ A shout from a room nearby.

‘You idiot. Fight with that purple firework!’

‘Hu …’ the person yells again.

There must be a cigarette. I bolt right up and roll off the bed. I raise my head towards the reflected light entering from outside. I bite on the end of the half-cigarette remaining from earlier and sit on an easy chair. Cigarettes are delicious. The doctors who say that cigarettes are unsanitary are idiots. They are the dumbest things on earth who can’t decipher what’s sanitary from what isn’t. When it comes to sanitation, there are two kinds: the physiological sanitation and the psychological sanitation. There’s the way to maintain one’s bodily health through mental conditioning, and the way to maintain it through physical sanitation. Cigarettes represent mental sanitation, and they can’t help but be that way. I inhale the cigarette smoke into my lungs and exhale it through my nose and mouth quietly, aiming for my cheeks. The train whistle blows sharply as though reacting to this with surprise. Someone yawns loudly. It’s the kind of yawn that throws up the living spirit. Frightening sounds enter my ears.

‘Ah, hey, ah, ah, ah, ayu, I’m gonna die … Hu …’

Terrifying objects appear before my eyes and inside my head. There’s a person whose head is split open lying on the bed. The left cheek is dark, completely covered in blood. The skull and forehead are wrapped in gauze. Below the dark skin are bloodshot eyes glistening. There’s no expression. The mouth is slightly parted. I fall in and disappear. I cry out but my mouth doesn’t move. My tongue prances about like boiling oil. The pain in my head feels like my brain is wearing a hat made of tens of thousands of needles. My body shivers. Brrr. Next to that bed is a person with an amputated arm. He moves just enough to keep the tiny bit of remaining arm hidden beneath the gauze. Next to that bed is a person without a leg. Beside that person is someone with a stomach split open. All kinds of shouting can be heard here. The cries are cursing life and the living. We’re been reduced to an intimate hell setting – no, we’ve expanded into one.

‘Die!’ someone cries out.

‘I’m gonna die …’ another cries out as though in reply.

But what is death? I think. Death is brown. Could it be anything else but that?

Brown. It’s brown. There’s no way to know. I realize just how bad my head has become.

Death is brown. And … I don’t know what else.

‘Ai. I’m gonna die, gonna die.’ I hear this from quite afar. I could foresee a final, terrible act.

‘I’ll kill you. You just wait. That’ll be more restful for you anyhow.’ I hobble up from the easy chair thinking of the penknife sitting amongst the scrap paper that I brought with me. My vision is still blurry. The brown column. White walls. As the black – no, blue – atmosphere turns into a vast endlessness, I think, I’m falling.

Before I am able to complete that thought, a flash appears before my eyes, and bang! I fall right in place.

Thought Piece Three

I still recall vividly. It had been my tenth night at the hospital. I was watching W playing with a bug before falling asleep. It was probably around five in the morning.

‘Hyŏngnim, hyŏngnim,’ I heard my younger brother call me.3 I was the designated owner of the house prior to my hospitalization. In the far room were my kid brother and my mother.

I eventually asked, ‘What?’

There was no reply. I waited a while. Again,

‘Hyŏngnim. Hyŏngnim.’

‘What?’ I repeated. I waited a while but, again, I heard nothing. I sat right up and pushed open the side door. There I found neither my brother nor my mother. Not only that but there wasn’t a single stick of furniture inside. It was a completely empty room shining clear and bright under the light. I stood up straight. Goosebumps rose all over my body. I stood there for two or three seconds before swiftly turning around to lie back down in place. Right then from the empty space around the corner appeared a strange monster. It was a brown demon. Both sides of its cheeks drooped down. His eyes were blank and without life. He appeared to be hiding a ferocity as sharp as a needle’s point.

‘It’s brown. It’s brown,’ I shouted from within.

As if it heard me, the demon started to laugh in a raspy voice, ‘Ha ha ha ha.’

I suddenly grew bold and asked, ‘What are you doing here?’

‘What am I doing? Why? Can’t I come here?’

‘Of course you can’t! You can’t!’

‘Come now. No need to be so angry. I was coming to get someone next door, and I stopped by to check in on you.’

‘You have no reason to be here.’

‘Well, you might become our henchman some day, so I stopped by to see you.’

‘Not me. No. I won’t be your henchman.’

‘Ha ha ha ha.’ Its raspy laughter was enough to break every object in the room.

‘So you have intentions to get involved with us?’

‘No involvement. I just won’t go where you are.’

‘For how many days …?’

‘How many? One month, two months, a year, five years, ten years, twenty years, fifty years, until I die …’

‘When do you think you’ll die?’

‘Only God knows that.’

‘Hŭng. God? That’s only something that I know.’

‘That’s a lie. That’s a lie!’

‘You’ll come to know once time passes. Ha ha ha ha ha. Let’s not do this. Let’s compromise and …’

‘I don’t need to compromise!’

‘When you join us in our world, I’ll grant you supreme power.’

‘Are you seducing me?’

‘Then what’ll you have to envy?’

‘A person can’t live on bread alone.’

‘Then what’s he live on, eh?’

‘With his vibrant strength! With life!’

‘That vibrant strength, that vibrant life … If you had “governing authority” don’t you think you’d be happy?’

‘I don’t want my rights to be pinned down by you!’

‘That’s exactly it … This is the weakness of you humans. Humans sacrifice their entire futures and lives fighting over their rights. You are indeed a weak item.’

‘No. Humans are mighty because of that!’

‘Ha ha ha ha. Humans are mighty, too? In our world, that’s the concern of the weakest beings …You wanna know?’ The demon grinned.

‘I don’t wanna know. I don’t wanna hear about it.’

‘Then why ask?’

‘I was just asking.’

‘Then I don’t need to explain?’

‘Don’t need? After I ask something I need to hear an answer.’

‘Ha ha ha ha. Indeed, you want to hear, eh? In our world, the strongest proclaims, “I absolutely will do what my heart desires.” Got it?’

‘Well, there you go. I, too, don’t want to go where you are, so I won’t ever go.’

‘That’s just a human being’s petty concern over what he doesn’t want to do. Now, in your heart, you want to go, right?’

‘I hate all of it. I’m just waiting for you to get out of here.’

‘You really hate me being here?’ the demon asked me, fuming in anger.

‘That’s right!’

‘If you hate it then I’ll just do this.’ With that, it stretched its claw-like hands and approached me.

‘Ah! Ah!’ I let out small cries. At this point I realized that this was a dream. I used all my strength to open my eyes. They flashed open.

A dream, I told myself, and continued to tread the dark path. Up ahead, I saw a light. Without any hesitation, I walked towards the light. There was no end. There’s no way to know where the end of the road is. I wasn’t sure how many hours – no, how many days – I had been walking. I eventually reached the light. It was an enormous palace – enough for me to wonder how such a house could even exist. I went inside. There was no way to know where the main entrance was. I was an uninvited stranger just wandering into somebody’s house. As soon as this occurred to me, I turned around to leave when suddenly I heard a voice say, ‘M. Why are you leaving? Please come in.’ I turned to look. It was a familiar face but a stranger’s nonetheless.

‘Who are you?’

‘Me? You met me earlier. Where is your head?’ I looked at him again. It was the demon. The brown demon. I turned and ran towards the darkness as the voice called after me, ‘Where are you going?’

I ran twenty-three thousand li. There was a house across from the palace. I ran inside, crying out to be saved. The house was the palace from earlier. I’d somehow returned to where I started. I turned and ran away again. I’m not sure how many times I went through this. Every house I arrived at was the original place I’d started from. I didn’t know what else to do so I ran away again. The eastern light gradually became brighter. From afar, a nasally voice cried out, ‘Help me.’ I ran towards the voice. It was an elderly man. He was also my younger brother.

‘Hyŏngnim, what’s wrong?’

‘Help me.’ He didn’t wait for an explanation. Without hesitation, he said that he knew of a being with infinite power and that we should go and request salvation. We ran together towards that direction. It was a magnificent home. After standing there for a bit, I went inside alone, found the owner and brought him out. Again – it was the brown demon.

‘Why do you keep following me?’ I shouted at him.

‘Me? Follow you? Didn’t you invade my home?’ he replied. ‘I shall end your life for you,’ he said as he unsheathed a sword.